Abstract

This cohort study characterizes the inclusion of Hispanic ethnicity or ethnoracial categories in breast cancer studies from the National Cancer Database.

According to US Census Bureau data, Hispanic individuals represent 18.7% of the US population and are the fastest growing demographic in the US.1 Despite this, the inclusion of Hispanic ethnicity as a covariate in studies is inconsistent, and disaggregation of Hispanic ethnicity by race is infrequent. For patients with breast cancer (BC), studies suggest that there are ethnoracial (eg, Hispanic Black, Hispanic White) differences in stage, treatment, and mortality.2 In this cohort study, we set to characterize the inclusion of Hispanic ethnicity or ethnoracial categories in BC studies from the National Cancer Database (NCDB).

Methods

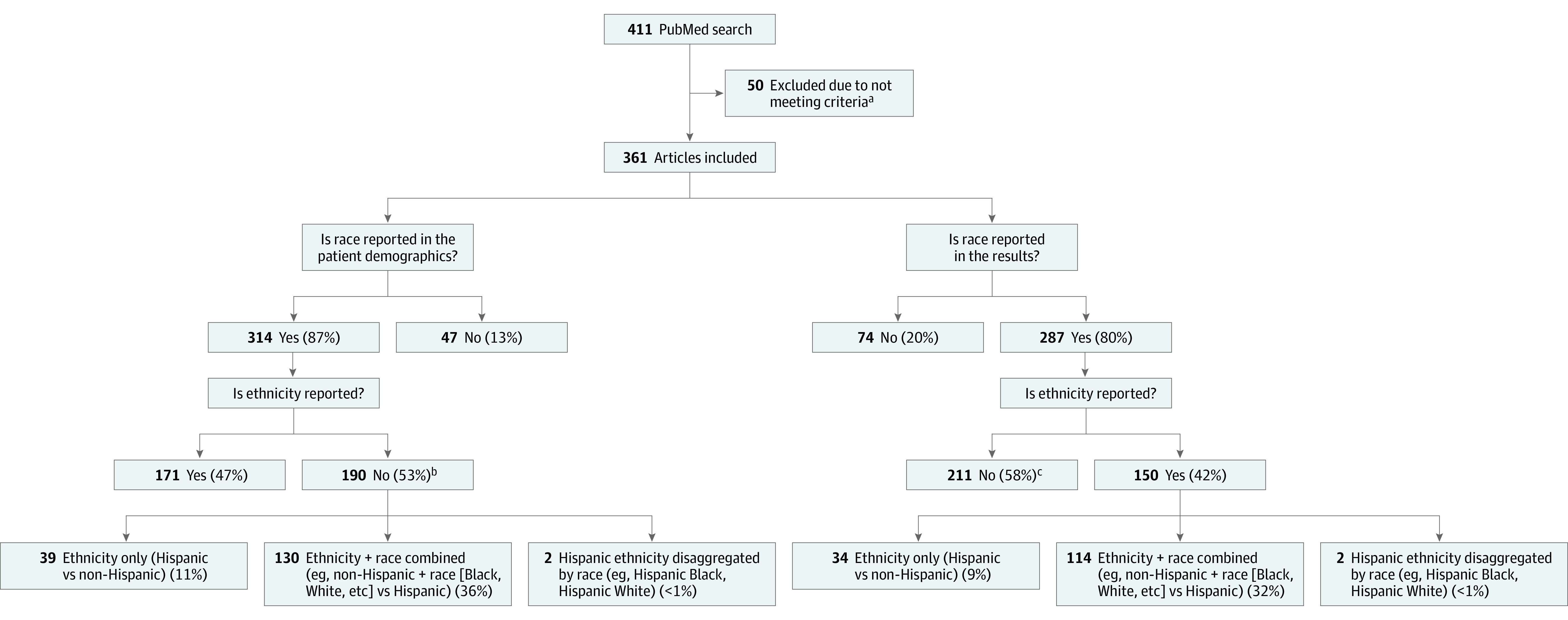

This study was exempt from institution review board approval owing to use of publicly available, deidentified data. The NCDB captures information from 70% of all cancers diagnosed in the US and includes both race and ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic). On November 23, 2021, we identified NCDB BC studies from 2010 through 2021 with the following advanced-feature PubMed search: ((“national cancer database”) OR (NCDB)) AND (breast cancer). Key exclusion criteria are reported in the Figure. We examined eligible studies for the inclusion of race and ethnicity in the patient demographics (PD) and results.

Figure. Flow Diagram of Included Studies.

aReasons for exclusion included studies with no patients with breast cancer, abstract only available, and review articles and commentaries.

bIncludes the 47 studies that excluded race.

cIncludes the 74 studies that excluded race.

Results

A total of 361 studies met inclusion criteria (Figure), with a median (IQR) sample size of 68 242 (11 660-352 646) patients. Ethnicity was included less frequently than race in the PD (171 [47%] vs 287 [87%] studies) and in the results (150 [42%] vs 287 [80%] studies) (Figure). Ethnicity was also less frequently reported in both the PD and results when compared with race (149 [41%] vs 284 [79%] studies) and was more likely to not be reported in either the PD or results (189 [52%] vs 44 [12%] studies) (Table). Mutually exclusive race and ethnicity groups (Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, and non-Hispanic White) were reported in the PD in 130 (36%) studies and in the results in 114 (32%) studies. Two studies (<1%) disaggregated Hispanic ethnicity by race.

Table. Frequency of Reporting Race and Ethnicity in Study Demographics and Results (n = 361).

| Section reported | Studies, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Race | Ethnicity | |

| Demographics and results | 284 (79) | 149 (41) |

| Demographics only | 30 (8) | 22 (6) |

| Results only | 3 (<1) | 1 (<1) |

| Neither demographics nor results | 44 (12) | 189 (52) |

Discussion

We demonstrated that Hispanic ethnicity is reported in fewer than 50% of NCDB BC studies, approximately one-third of NCDB BC studies categorized race and ethnicity into mutually exclusive groups (Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, and non-Hispanic White), and less than 1% disaggregated ethnoracial categories for both Hispanic and non-Hispanic people. While there are limitations in interpreting NCDB study results, these findings are noteworthy because excluding ethnicity from any analysis results in missed opportunities to identify differences in patient and treatment characteristics as well as survival, which may be less or more favorable in Hispanic people.3,4 We focused this analysis on the NCDB because it is the largest hospital-based registry of patients with BC in the US. Our future studies will examine population-based registries such as the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program, which includes a race and ethnicity recode variable that categorizes patients as Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, and non-Hispanic White, among others.

The diversity of the Hispanic population may result in differences in outcomes based on country of origin5 or race, as highlighted by data demonstrating that disaggregating race and ethnicity (eg, non-Hispanic Black vs Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White vs Hispanic White) reveals differences in outcomes that may not be appreciated by analyzing the data with non-Hispanic White as the reference group.2 However, US Census Bureau data demonstrate that individuals who identify as Hispanic most commonly identify their race as “some other race” (42.2%), while only 1.8% identify as Black or African American and 20.3% as White.1 Therefore, identifying truly Hispanic Black or Hispanic White individuals remains a challenge in interpretation and categorization of disaggregated self-identified ethnoracial data.

In this cohort study we demonstrate a considerable gap in race and ethnicity reporting in NCDB BC studies. These results are meaningful when contextualized within the race and ethnicity reporting guidance from JAMA.6 Future studies should categorize patients by both race and ethnicity and report country of origin when available. The inclusion of distinct ethnoracial categories will further improve the understanding of the influence of ethnoracial differences in experiences of systemic inequity, structural racism, and discrimination, as well as their effects on BC outcomes.

References

- 1.Race and ethnicity in the United States: 2010 Census and 2020 Census. US Census Bureau . August 12, 2021. Accessed July 28, 2022. https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/interactive/race-and-ethnicity-in-the-united-state-2010-and-2020-census.html

- 2.Champion CD, Thomas SM, Plichta JK, et al. Disparities at the intersection of race and ethnicity: examining trends and outcomes in Hispanic women with breast cancer. JCO Oncol Pract. 2022;18(5):e827-e838. doi: 10.1200/OP.20.00381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carey LA, Perou CM, Livasy CA, et al. Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study. JAMA. 2006;295(21):2492-2502. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.21.2492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warner ET, Tamimi RM, Hughes ME, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in breast cancer survival: mediating effect of tumor characteristics and sociodemographic and treatment factors. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(20):2254-2261. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.1349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riner AN, Underwood PW, Yang K, et al. Disparities in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma—the significance of Hispanic ethnicity, subgroup analysis, and treatment facility on clinical outcomes. Cancer Med. 2020;9(12):4069-4082. doi: 10.1002/cam4.3042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flanagin A, Frey T, Christiansen SL; AMA Manual of Style Committee . Updated guidance on the reporting of race and ethnicity in medical and science journals. JAMA. 2021;326(7):621-627. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.13304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]