Abstract

BACKGROUND

Ewing sarcoma (ES) is an aggressive small round cell tumor that usually occurs in younger children and young adults but rarely in older patients. Its occurrence in elderly individuals is rare. ES of the ileum with wide multiorgan metastases is rarely reported and difficult to distinguish radiologically from other gastrointestinal tract tumors.

CASE SUMMARY

A 53-year-old man presented with right lower quadrant pain for 2 wk. Computed tomography results showed a heterogeneous mass within the ileum and widespread multiorgan metastases. This mass was biopsied, and pathological examination of the resected specimen revealed features consistent with an extraskeletal ES.

CONCLUSION

This case emphasizes the importance of recognizing this rare presentation in the small intestine to broaden the differential diagnosis of adult intraabdominal tumors.

Keywords: Ewing sarcoma, Intestinal neoplasms, Neoplasm metastasis, Oncology, Carcinoma, Case report

Core Tip: Ewing’s sarcoma (EOES) originating in the ileum with wide multiorgan metastases is rare and easily misdiagnosed. When a small intestine mass accompanied by calcification and wide multiorgan metastases is seen on computed tomography, a suspicion of EOES should not be overlooked. Together with previous reports, this case expands knowledge regarding the spectrum of tumors in the small intestine.

INTRODUCTION

Ewing sarcoma (ES) of the bone represents the second most common primary malignant tumor of bone in children and adolescents, exceeded in prevalence only by osteosarcoma[1]. Osseous ES, together with extraosseous Ewing’s sarcoma (EOES), primitive neuroectodermal tumor, and Askin’s tumor are members of the Ewing sarcoma family of tumors[1,2]. The treatment of EOES patients includes chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and surgery. To date, the 5-year survival rate of EOES is relatively high (65%-75%)[3]. The outcome for metastatic patients is usually poor (< 30%), despite the use of surgery, chemo- and/or radiotherapy. EOES is rarer than ES of the bone. The prevalence of EOES is generally accepted to be between 15% and 20% of that of ES of the bone[2]. The most common sites of EOES are the paravertebral region, lower extremities, chest wall and retroperitoneum[4]. To our knowledge, EOES originating in the ileum is not common, with only nearly 30 cases reported worldwide. However, there were few reports regarding EOES of the ileum with multiorgan metastases at the time of diagnosis[5-7]. In this paper, we present a case with an initial diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), but histopathology indicated EOES with widespread multiorgan metastases.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 53-year-old man suffered from right lower quadrant abdominal pain for 2 wk.

History of present illness

The patient experienced right lower quadrant abdominal pain for 2 wk, accompanied by acid reflux, belching, and emesis (an oral discharge without digested food and hematemesis), but denied having fevers, night sweats, unintentional weight loss, and blood in the stool.

History of past illness

The patient had a medical history free of previous diseases.

Personal and family history

The patient denied that the family had any genetic diseases. There was no similar disease in the family.

Physical examination

On physical examination, the patient’s abdomen was soft with tenderness on the right side abdominal without rebound tenderness or muscle guarding, and normal bowel sounds were present. In palpation, a mass with unclear boundary was identified in the right lower abdomen, measuring 4 cm × 6 cm approximately, and the mass can be mobile.

Laboratory examinations

After admission, laboratory investigations showed slightly increased levels of monocytes (0.987 × 109/L; normal range: 0.10–0.60 × 109/L), decreased eosinophil rate (0.1%; normal range: 0.4%-8%), decreased hemoglobin levels (119 g/L; normal range: 130-175 g/L), and prealbumin levels (14.9 mg/dL; normal range: 16-45 mg/dL), and increased platelet count (418 × 109/L; normal range: 85-303 × 109/L). All serum tumor marker levels were normal.

Imaging examinations

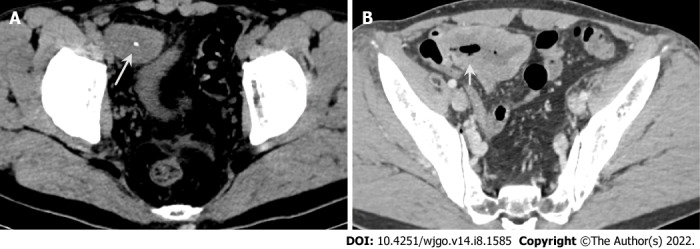

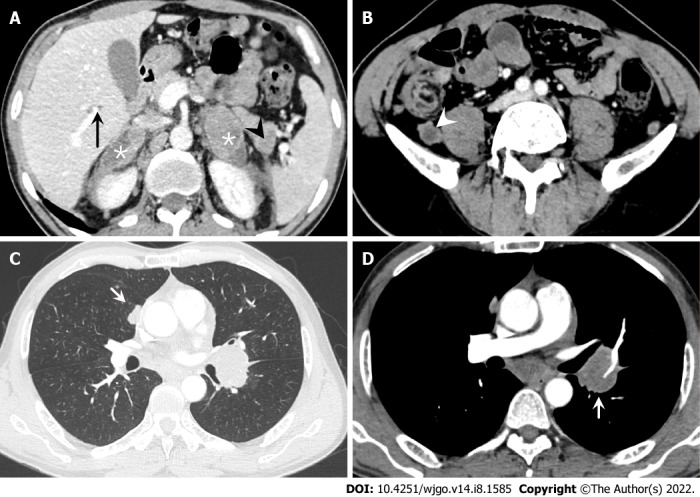

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen showed an 8.1 cm × 4.0 cm mass in the right iliac fossa area, which interacted with the small intestinal lumen. The mass was heterogenetic, and areas of low attenuation and high attenuation were observed, likely corresponding to areas of necrosis and calcification (Figure 1). In addition, multiple metastatic lesions were observed on the bilateral adrenal gland, lung, liver and pancreas, and several enlarged lymph nodes were seen in the retroperitoneal and mediastinum areas, with the largest exhibiting a diameter of 2.3 cm (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Abdominal computed tomography. A: Axial computed tomography (CT) image shows a heterogenetic mass with calcification (white arrows); B: Contrast-enhanced CT shows mild heterogenetic enhancement and communication with the small intestinal lumen (short white arrows).

Figure 2.

Abdominal and chest computed tomography. A: Multiple metastatic lesions are observed on the bilateral adrenal gland (*), liver (black arrow) and pancreas (black arrowhead); B: Several enlarged lymph nodes (white arrowhead) are seen on the retroperitoneal area; C: A pulmonary metastatic nodule (short white arrow) is seen in lung windows; D: Several enlarged lymph nodes (short white arrow) are shown on the mediastinum area in contrast-enhanced computed tomography.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY EXPERT CONSULTATION

From the contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen and chest, multidisciplinary consultation determined that malignant GISTs with widespread multiorgan metastases were first considered. The patient could not receive surgical treatment because of widespread multiorgan metastases. Therefore, adjuvant chemotherapy was recommended.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

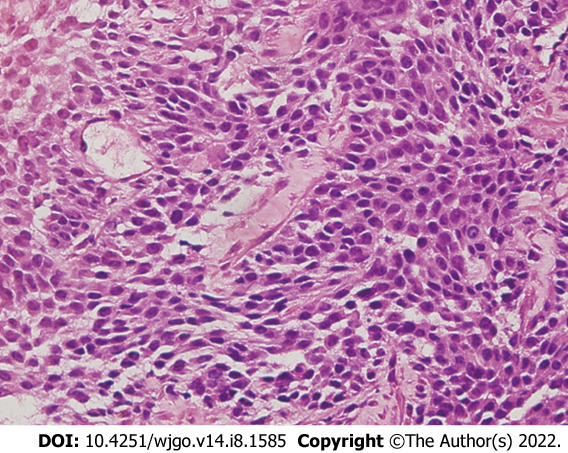

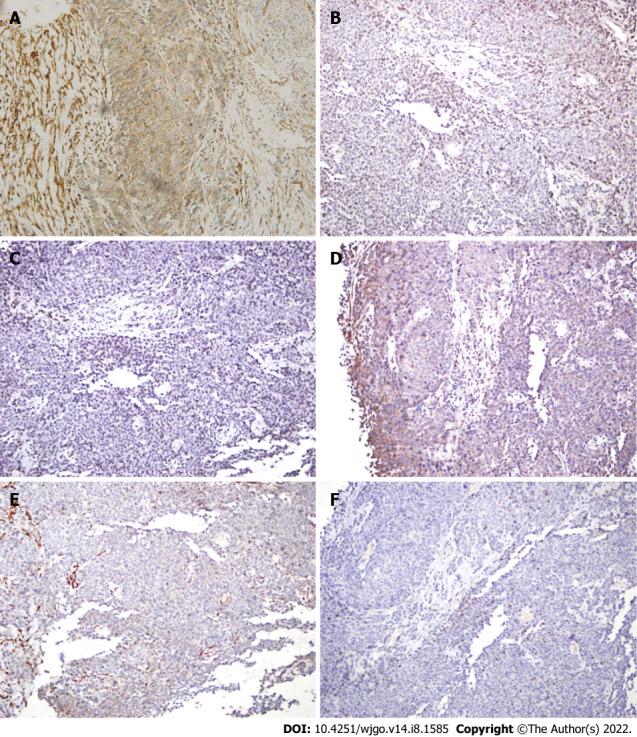

To make the diagnosis, transabdominal ultrasound guided needle biopsy was performed with the consent of the patient. The biopsy was performed as an outpatient procedure under local anesthesia. Histopathology of the small intestinal tumor is composed of heteromorphic cells, and distributed in the shape of a sheet nest with round or oval cells and visible nucleoli (Figure 3). Tumor cells showed positive immunoreactivity for CD99, NKX2.2, S100, Syn and Ki-67, and the Ki-67 Level was greater than 60%. The results were negative for CK, CgA, CK5/6, P63, CK7, CAM5.2, CK20, CD56, CD117 and alpha-inhibin (Figure 4). Therefore, the histopathologic findings were consistent with EOES. Although without molecular biological examination, after multidisciplinary consultation, the clinician concluded the diagnosis was primary small intestinal ES because of the positive immunoreactivity for NKX2.2, FLI-1 and CD99 combined with morphological characteristics.

Figure 3.

Pathologic findings. Histopathology of the small intestinal tumor is composed of heteromorphic cells, and distributed in the shape of sheet or nest with round or oval cells and visible nucleoli. (Original magnification 400 ×; hematoxylin-eosin stains).

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry findings. A: Strong positive staining for CD99 (original magnification 200 ×); B: Positive staining for NKX2.2 original magnification 200 ×); C: Positive staining for FLI-1 (original magnification 200 ×); D: Positive staining for Syn (original magnification 200 ×); E: Negative immunoreactivity for CK (original magnification 200 ×); F: Negative immunoreactivity for CgA (original magnification 200 ×).

TREATMENT

After multidisciplinary consultation, the physicians recommended 5 cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy with vincristine, ifosfamide, and doxorubicin for the patient, which could reduce the size of the primary tumor and metastases. However, the patient refused this treatment strategy. The patient was given fluid rehydration (0.9% sodium chloride solution, 5% glucose sodium chloride injection), nutritional support (Compound amino acid injection, 20% medium and long chain fat emulsion injection and ω-3 fish oil fat emulsion injection) and intravenous injection of parecoxib sodium 40 mg to relieve the pain.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

One month later, the patient could not eat and received symptomatic nutritional support (Compound amino acid injection, 20% medium and long chain fat emulsion injection and ω-3 fish oil fat emulsion injection) and analgesic treatment (intravenous injection of parecoxib sodium 40 mg). Despite the medical advice, the patient refused to receive any systemic treatment. The patient chose to be transferred to hospice care ward and died of multiple organ failure caused by widespread multiorgan metastases 2-mo later.

DISCUSSION

ES most commonly arises from bone but can develop in extraskeletal sites. In contrast, half or more of primary adult cases are EOES[4]. ES exhibits the highest incidence in older adolescents, with patients aged over 40 years experiencing extraskeletal tumors, metastatic spread at the time of diagnosis, and shorter survival than younger patients. It shows aggressive clinical behavior with a high rate of local recurrence and distant metastasis[8]. Approximately 15%-46% of patients will demonstrate metastatic disease at presentation, reducing 5-year survival from approximately 35%-71% to a dismal 0-34%[9].

We have summarized all previous publications of small intestinal ES/PNET in Table 1[10-26]. The patient gender ratio (female/male) was 12/15. The ages ranged from 9 to 69 years, and 60% of patients with small intestinal ES were younger than 30 years. The most common sites in patients with metastatic disease are the liver and peritoneum. Adrenal metastases have rarely been described[7]. Seven patients had metastases to the liver and peritoneum solitarily. Only one patient had metastases to the adrenal gland and peritoneum at the time of diagnosis. Patients of more than 40 years of age or with metastatic spread at the time of diagnosis have shorter survival than younger patients. The form of distant metastasis included seeding, blood and lymphatic vessel metastasis. The mechanism of distant metastasis from the ES in the ileum to other organs could be explained for two reasons. First, hematogenous metastasis may occur because the tumor cells penetrate and spread from the vessels in the ileum. Second, there are abundant lymphatic networks in the submucosal layer of the ileum, and the lymphatics intermittently pierce the muscularis propria and drain into regional lymph nodes in the peritoneum. The tumor cells penetrate and spread from lymphatics to regional lymph nodes or even distal lymph nodes.

Table 1.

Reported cases of Ewing Sarcoma of small bowel

|

Site

|

Age

|

Sex

|

Metastasis at diagnosis

|

Treatments

|

Follow-up

|

Ref.

|

| Small intestine | 21 | F | - | Sx + Cx | 10 mo DFS | Adair et al [10], 2001 |

| Jejunum | 13 | M | - | Sx | 1 yr DFS | Sarangarajan et al[11], 2001 |

| Distalileum | 14 | M | - | Sx + Cx | 10 mo DFS | Graham et al[12], 2002 |

| Small intestine | 9 | F | - | Sx + Cx | Died 25 mo after diagnosis | Shek et al[13], 2001 |

| Terminal Ileum andJejunum | 63 | M | Adrenal glands + lymph nodes | Sx + Cx | ND | Kim et al[7], 2007 |

| Terminal Ileum | 44 | M | Intra-peritoneal | Sx + Cx | Died 13 mo after diagnosis | Sethi and Smith[14], 2007 |

| Ileum | 32 | M | - | Sx + Cx | 6 mo DFS | Rodarte-Shade et al[15], 2012 |

| Terminal Ileum | 15 | F | - | Sx + Cx | ND | Vignali et al[16], 2012 |

| Ileum | 18 | M | - | Sx + Cx | ND | Boehm et al[6], 2003 |

| Ileum | 18 | M | Liver | Sx | Died 8 mo after diagnosis | Milione et al[4], 2014 |

| Ileum | 20 | M | Liver | Sx + Cx | Died 28 mo after diagnosis | Milione et al[4], 2014 |

| Ileum | 42 | M | - | Sx + Cx | Died 11 16 mo after diagnosis | Milione et al[4], 2014 |

| Ileum | 45 | M | - | Sx + Cx | Died 13 mo after diagnosis | Milione et al[4], 2014 |

| Ileum | 15 | F | - | Sx + Cx + Rx | 28 mo DFS | Milione et al[4], 2014 |

| Ileum | 57 | M | - | Lost | Lost | Milione et al[4], 2014 |

| Ileum | 28 | F | Liver | Sx + Cx | 204 mo DFS | Milione et al[4], 2014 |

| ileum | 16 | F | - | Sx | 6 mo DFS | Li et al[17], 2017 |

| Ileum | 69 | M | Intra-peritoneal | Sx | Died 8 mo after diagnosis | Yang et al[18], 2021 |

| Terminal Ileum | 57 | F | - | Sx + Cx | 8 mo DFS | Bala et al[19], 2006 |

| Small intestine | 66 | M | - | Sx + Cx | 48 mo DFS | Batziou et al[20], 2006 |

| Ileum | 22 | M | Liver | Sx | NA | Peng et al[21], 2015 |

| Jejunum | 9 | F | Peritoneum | Sx + Cx | NA | Kim et al[7], 2017 |

| Jejunum | 67 | F | - | Sx | 3 mo DFS | Cantu et al[22], 2019 |

| Jejunum | 42 | M | - | Sx + Cx | 9 mo DFS | Yagnik et al[23], 2019 |

| Jejunum | 30 | F | - | Sx | 2 mo DFS | Kolosov et al[24], 2020 |

| Ileum | 17 | F | - | Sx | NA | Paricio et al[25], 2021 |

| Duodenum | 25 | F | - | Sx | Died 1 mo after diagnosis | Hassan et al[26], 2022 |

F: Female; M: Male; Sx: Surgery; Cx: Chemotherapy; Rx: Radiotherapy; DFS: Disease free survival; NA: Not available.

The most frequently presenting symptom is a rapidly growing mass with local pain. However, the accompanying symptoms depend largely on the sarcoma site[27]. Our patient complained of right lower quadrant pain accompanied by acid reflux, belching, and emesis. CT showed a large, sharply delineated mass of relatively lower or equal density to that of the adjacent muscle. After enhancement, the mass showed heterogenetic enhancement with intratumor necrosis and calcification. Calcification is seen in 25%-30% of previous cases[1]. This patient had metastases of the bilateral adrenal gland, liver, pancreas and lung and multiple regional lymph node metastases. These findings represent necrotic changes common in both EOES and its metastases, which reflect the disease’s aggressive nature[2].

For differentiation of Ewing sarcoma from the other small round cell tumors, molecular detection of specific fusion genes is recommended, which accepted as the gold standard method for diagnosing Ewing sarcoma[17]. However, this patient did not do this due to a small tissue sample size. Immunohistochemistry has emerged as a compelling alternative. NKX2.2, CD99 and FLI-1 are good immunohistochemical markers for ES. NKX2.2 was shown to be a valuable immunohistochemical marker for ES in the differential diagnosis of small round cell tumors, which has been identified as an important target of EWS-FLI-1[28,29]. A few number of non-Ewing tumors can be positive for NKX2.2, such as synovial sarcomas, mesenchymal chondrosarcomas, and malignant melanomas. Nuclear spindling and TLE1 immunoreactivity favor synovial sarcomas[30]. NKX2.2-positive synovial sarcoma exhibited weak focal staining compared to diffuse labeling of ES. Mesenchymal chondrosarcomas could be excluded based on histology and immunohistochemical data[31]. Malignant melanomas could be excluded because the tumor did not express specific melanoma markers (e.g., HMB45 and Melan A)[32]. According to the exclusive diagnosis, the present case was ultimately diagnosed as synchronous ES.

The imaging characteristics of the small intestinal ES are nonspecific as well. The major differential diagnosis for small intestinal ES includes GIST, lymphoma, adenocarcinoma, neuroendocrine neoplasm and metastatic lesions. GISTs are the most common mesenchymal tumors in the gastrointestinal tract and typically present as submucosal tumors of the gastrointestinal wall, occasionally accompanied by mucosal ulcers and tumor rupture[33]. GISTs occurring in the small intestinal characteristically have hemorrhage, necrosis, or cyst formation that appears as focal areas of low attenuation on computed tomographic images, and may present with cavity and fistula formation[34]. Moreover, GISTs rarely exhibit regional lymph node metastasis, unlike the mass presenting with multiple regional lymph node metastases in our patient. Intestinal lymphoma classically presents with a thickened wall and paradoxical dilatation but no obstruction, potentially with lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly[35]. And it often shows mild enhancement and the presence of vessel floating signs. In addition, lymphoma rarely presents with multiorgan metastases[36]. Intestinal adenocarcinoma typically shows irregular or annular thickening of the intestinal wall resulting in luminal narrowing, which may result in intestinal obstruction. Small intestinal neuroendocrine neoplasms may have mural transgression with the invasion of the serosa and mesentery and may conglomerate into spiculated masses with frequent calcification and surrounding lymphadenopathy[37,38]. Tumor metastasis to the small intestine is extremely rare, and few reports indicate in the literature[39].

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy was initially used to eliminate micrometastases and reduce the size of the primary tumor[40]. ES is quite radiosensitive, and some researchers have emphasized the important role of preoperative radiotherapy for successful local treatment in spinal ES[41]. However, improvements in surgical technique and the risks associated with radiation (secondary malignancies) have reduced the reliance on radiation[42]. Surgery alone does not appear to be effective for metastatic ES due to technical difficulties related to surgery and a low survival rate. This case will contribute to understanding the prognosis and determination of optimal management because small bowel ES is extremely rare and difficult to cure.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, EOES originating in the ileum with widespread multiorgan metastases is rare and easily misdiagnosed. When a small intestinal mass accompanied by calcification and wide multiorgan metastases is seen on CT, a suspicion of EOES should not be overlooked. Together with previous reports, this case has expanded knowledge about the spectrum of tumors in the small intestine.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to the families, friends and colleagues who support our work.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: The patient involved in this study gave his written consent authorizing use and disclosure of his protected health information.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All authors report no relevant conflict of interest for this article.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklis (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: March 13, 2022

First decision: April 17, 2022

Article in press: July 11, 2022

Specialty type: Radiology, nuclear medicine and medical imaging

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): D, D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Agarwal P, India; Bredt LC, Brazil; Li Y, China; Soldera J, Brazil; Yarso KY, Indonesia S-Editor: Wu YXJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wu YXJ

Contributor Information

Ai-Wen Guo, Department of Radiology, Affiliated Hospital of Medical School, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Sichuan Academy of Medical Sciences and Sichuan Provincial People's Hospital, Chengdu 610072, Sichuan Province, China; Department of Radiology, Chengdu Women's and Children's Central Hospital, School of Medicine, Chengdu 611731, Sichuan Province, China.

Yi-Sha Liu, Department of Pathology, Affiliated Hospital of Medical School, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Sichuan Academy of Medical Sciences and Sichuan Provincial People's Hospital, Chengdu 610072, Sichuan Province, China.

Hang Li, Department of Radiology, Affiliated Hospital of Medical School, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Sichuan Academy of Medical Sciences and Sichuan Provincial People's Hospital, Chengdu 610072, Sichuan Province, China. lihang111222@126.com.

Yi Yuan, Department of Radiology, Affiliated Hospital of Medical School, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Sichuan Academy of Medical Sciences and Sichuan Provincial People's Hospital, Chengdu 610072, Sichuan Province, China.

Si-Xun Li, Department of Radiology, Affiliated Hospital of Medical School, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Sichuan Academy of Medical Sciences and Sichuan Provincial People's Hospital, Chengdu 610072, Sichuan Province, China.

References

- 1.Murphey MD, Senchak LT, Mambalam PK, Logie CI, Klassen-Fischer MK, Kransdorf MJ. From the radiologic pathology archives: ewing sarcoma family of tumors: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2013;33:803–831. doi: 10.1148/rg.333135005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Javery O, Krajewski K, O'Regan K, Kis B, Giardino A, Jagannathan J, Ramaiya NH. A to Z of extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma family of tumors in adults: imaging features of primary disease, metastatic patterns, and treatment responses. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197:W1015–W1022. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.6667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galyfos G, Karantzikos GA, Kavouras N, Sianou A, Palogos K, Filis K. Extraosseous Ewing Sarcoma: Diagnosis, Prognosis and Optimal Management. Indian J Surg. 2016;78:49–53. doi: 10.1007/s12262-015-1399-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Milione M, Gasparini P, Sozzi G, Mazzaferro V, Ferrari A, Casali PG, Perrone F, Tamborini E, Pellegrinelli A, Gherardi G, Arrigoni G, Collini P, Testi A, De Paoli E, Aiello A, Pilotti S, Pelosi G. Ewing sarcoma of the small bowel: a study of seven cases, including one with the uncommonly reported EWSR1-FEV translocation. Histopathology. 2014;64:1014–1026. doi: 10.1111/his.12350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El Weshi A, Allam A, Ajarim D, Al Dayel F, Pant R, Bazarbashi S, Memon M. Extraskeletal Ewing's sarcoma family of tumours in adults: analysis of 57 patients from a single institution. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2010;22:374–381. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boehm R, Till H, Landes J, Schmid I, Joppich I. Ileoileal intussusception caused by a Ewing sarcoma tumour. An unusual case report. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2003;13:272–275. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-42234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim DW, Chang HJ, Jeong JY, Lim SB, Lee JS, Hong EK, Lee GK, Choi HS, Jeong SY, Park JG. Ewing's sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor (ES/PNET) of the small bowel: a rare cause of intestinal obstruction. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:1137–1138. doi: 10.1007/s00384-006-0142-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Worch J, Ranft A, DuBois SG, Paulussen M, Juergens H, Dirksen U. Age dependency of primary tumor sites and metastases in patients with Ewing sarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65:e27251. doi: 10.1002/pbc.27251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esiashvili N, Goodman M, Marcus RB Jr. Changes in incidence and survival of Ewing sarcoma patients over the past 3 decades: Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results data. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2008;30:425–430. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31816e22f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adair A, Harris SA, Coppen MJ, Hurley PR. Extraskeletal Ewings sarcoma of the small bowel: case report and literature review. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 2001;46:372–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarangarajan R, Hill DA, Humphrey PA, Hitchcock MG, Dehner LP, Pfeifer JD. Primitive neuroectodermal tumors of the biliary and gastrointestinal tracts: clinicopathologic and molecular diagnostic study of two cases. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2001;4:185–191. doi: 10.1007/s100240010141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graham DK, Stork LC, Wei Q, Ingram JD, Karrer FM, Mierau GW, Lovell MA. Molecular genetic analysis of a small bowel primitive neuroectodermal tumor. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2002;5:86–90. doi: 10.1007/s10024-001-0192-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shek TWH, Chan GCF, Khong PL, Chung LP, Cheung ANY. Ewing Sarcoma of the Small Intestine. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2001;23:530–532. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200111000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sethi B, Smith GT. Primary primitive neuroectodermal tumour arising in the small bowel. Histopathology. 2007;50:665–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodarte-Shade M, Palomo-Hoil R, Vazquez J, Ancer A, Vilches N, Flores-Gutierrez JP, Sierra M, Garza-Serna U. Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumor (PNET) of the Small Bowel in a Young Adult with Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2012;43:S243–S245. doi: 10.1007/s12029-012-9409-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vignali M, Zacchè MM, Messori P, Natale A, Busacca M. Ewing's sarcoma of the small intestine misdiagnosed as a voluminous pedunculated uterine leiomyoma. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;162:234–235. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li T, Zhang F, Cao Y, Ning S, Bi Y, Xue W, Ren L. Primary Ewing's sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the ileum: case report of a 16-year-old Chinese female and literature review. Diagn Pathol. 2017;12:37. doi: 10.1186/s13000-017-0626-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang J, Wei H, Lin Y, Lin N, Wu S, Yu X. Challenges of Diagnosing Primary Ewing's Sarcoma in the Small Intestine of the Elderly: A Case Report. Front Oncol. 2021;11:565196. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.565196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bala M, Maly A, Remo N, Gimmon Z, Almogy G. Peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor of bowel mesentery in adults. Isr Med Assoc. 8:515–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Batziou C, Stathopoulos GP, Petraki K, Papadimitriou C, Rigatos SK, Kondopodis E, Stathopoulos J, Batzios S. Primitive neurectodermal tumors: a case of extraosseous Ewing's sarcoma of the small intestine and review of the literature. J buon. 2006;11:519–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peng L, Yang L, Wu N, Wu BO. Primary primitive neuroectodermal tumor arising in the mesentery and ileocecum: A report of three cases and review of the literature. Exp. 9:1299–1303. doi: 10.3892/etm.2015.2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cantu C, Bressler E, Dermawan J, Paral K. Extraskeletal Ewing Sarcoma of the Jejunum: A Case Report. Perm J. 2019;23:255. doi: 10.7812/TPP/18-255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yagnik VD, Dawka S. Extraskeletal Ewing's sarcoma/peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the small bowel presenting with gastrointestinal perforation. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2019;12:279–285. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S203697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kolosov A, Dulskas A, Pauza K, Selichova V, Seinin D, Stratilatovas E. Primary Ewing's sarcoma in a small intestine - a case report and review of the literature. BMC Surg. 2020;20:113. doi: 10.1186/s12893-020-00774-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paricio JJ, Ruiz Martín J, Sánchez Díaz E. Primary Ewing's sarcoma of the small intestine. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2021;113:680. doi: 10.17235/reed.2021.7735/2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hassan R, Meng LV, Ngee KT, I-Vern L, Sankaran P, Hean LC, Euxian L, Mohamad H, Dusa NM, Subramaniam M. Extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma of the duodenum presenting as duodenojejunal intussusception. The Lancet. 2022;399:1265. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00361-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Applebaum MA, Goldsby R, Neuhaus J, DuBois SG. Clinical features and outcomes in patients with Ewing sarcoma and regional lymph node involvement. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59:617–620. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith R, Owen LA, Trem DJ, Wong JS, Whangbo JS, Golub TR, Lessnick SL. Expression profiling of EWS/FLI identifies NKX2.2 as a critical target gene in Ewing's sarcoma. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:405–416. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoshida A, Sekine S, Tsuta K, Fukayama M, Furuta K, Tsuda H. NKX2.2 is a useful immunohistochemical marker for Ewing sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:993–999. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31824ee43c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Terry J, Saito T, Subramanian S, Ruttan C, Antonescu CR, Goldblum JR, Downs-Kelly E, Corless CL, Rubin BP, van de Rijn M, Ladanyi M, Nielsen TO. TLE1 as a diagnostic immunohistochemical marker for synovial sarcoma emerging from gene expression profiling studies. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:240–246. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213330.71745.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Owen LA, Kowalewski AA, Lessnick SL. EWS/FLI mediates transcriptional repression via NKX2.2 during oncogenic transformation in Ewing's sarcoma. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1965. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wehrli BM, Huang W, De Crombrugghe B, Ayala AG, Czerniak B. Sox9, a master regulator of chondrogenesis, distinguishes mesenchymal chondrosarcoma from other small blue round cell tumors. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:263–269. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2003.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamamoto H, Oda Y. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor: recent advances in pathology and genetics. Pathol Int. 2015;65:9–18. doi: 10.1111/pin.12230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levy AD, Remotti HE, Thompson WM, Sobin LH, Miettinen M. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: radiologic features with pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2003;23:283–304. doi: 10.1148/rg.232025146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hayashi D, Devenney-Cakir B, Lee JC, Kim SH, Cheng J, Goldfeder S, Choi BI, Guermazi A. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma: multimodality imaging and histopathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195:W105–W117. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.4105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mendelson RM, Fermoyle S. Primary gastrointestinal lymphomas: a radiological-pathological review. Part 1: Stomach, oesophagus and colon. Australas Radiol. 2005;49:353–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1673.2005.01457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salyers WJ, Vega KJ, Munoz JC, Trotman BW, Tanev SS. Neuroendocrine tumors of the gastrointestinal tract: Case reports and literature review. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2014;6:301–310. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v6.i8.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malla S, Kumar P, Madhusudhan KS. Radiology of the neuroendocrine neoplasms of the gastrointestinal tract: a comprehensive review. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2021;46:919–935. doi: 10.1007/s00261-020-02773-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yuan Y, Pu H, Pang MH, Liu YS, Li H. Thymic carcinoma metastasize to the small intestine: a case report. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020;20:358. doi: 10.1186/s12876-020-01505-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DuBois SG, Krailo MD, Gebhardt MC, Donaldson SS, Marcus KJ, Dormans J, Shamberger RC, Sailer S, Nicholas RW, Healey JH, Tarbell NJ, Randall RL, Devidas M, Meyer JS, Granowetter L, Womer RB, Bernstein M, Marina N, Grier HE. Comparative evaluation of local control strategies in localized Ewing sarcoma of bone: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. Cancer. 2015;121:467–475. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vogin G, Helfre S, Glorion C, Mosseri V, Mascard E, Oberlin O, Gaspar N. Local control and sequelae in localised Ewing tumours of the spine: a French retrospective study. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1314–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dunst J, Schuck A. Role of radiotherapy in Ewing tumors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2004;42:465–470. doi: 10.1002/pbc.10446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]