Abstract

Eremosparton songoricum (Litv.) Vass. is a rare leafless legume shrub endemic to central Asia which grows on bare sand. It shows extreme drought tolerance and is being developed as a model organism for investigating morphological, physiological, and molecular adaptations to harsh desert environments. APETALA2/Ethylene Responsive Factor (AP2/ERF) is a large plant transcription factor family that plays important roles in plant responses to various biotic and abiotic stresses and has been extensively studied in several plants. However, our knowledge on the AP2/ERF family in legume species is limited, and no respective study was conducted so far on the desert shrubby legume E. songoricum. Here, 153 AP2/ERF genes were identified based on the E. songoricum genome data. EsAP2/ERFs covered AP2 (24 genes), DREB (59 genes), ERF (68 genes), and Soloist (2 genes) subfamilies, and lacked canonical RAV subfamily genes based on the widely used classification method. The DREB and ERF subfamilies were further divided into A1–A6 and B1–B6 groups, respectively. Protein motifs and exon-intron structures of EsAP2/ERFs were also examined, which matched the subfamily/group classification. Cis-acting element analysis suggested that EsAP2/ERF genes shared many stress- and hormone-related cis-regulatory elements. Moreover, the gene numbers and the ratio of each subfamily and the intron-exon structures were systematically compared with other model plants ranging from algae to angiosperms, including ten legumes. Our results supported the view that AP2 and ERF evolved early and already existed in algae, whereas RAV and DREB began to appear in moss species. Almost all plant AP2 and Soloist genes contained introns, whereas most DREB and ERF genes did not. The majority of EsAP2/ERFs were induced by drought stress based on RNA-seq data, EsDREBs were highly induced and had the largest number of differentially expressed genes in response to drought. Eight out of twelve representative EsAP2/ERFs were significantly up-regulated as assessed by RT-qPCR. This study provides detailed insights into the classification, gene structure, motifs, chromosome distribution, and gene expression of AP2/ERF genes in E. songoricum and lays a foundation for better understanding of drought stress tolerance mechanisms in legume plants. Moreover, candidate genes for drought-resistant plant breeding are proposed.

Keywords: AP2/ERF genes, Eremosparton songoricum, drought stress, gene structure, gene expression, legume plant

Introduction

Drought is a major abiotic stress for plants, which can disrupt or prevent seed germination and growth and reduces yield (Lamaoui et al., 2018; Priya et al., 2019). Plants have evolved diverse morphological, biochemical, physiological, and molecular adaptations to changing environments (Valliyodan and Nguyen, 2006). Particularly plants inhabiting harsh environments, such as deserts or highly saline habitats, have evolved strategies to adapt to such stress conditions. Eremosparton songoricum (Litv.) Vass. is a rare and extremely drought-tolerant legume shrub distributed in Central Asia; its distribution is fragmented, and it occurs around Balkhash Lake in Kazakhstan and the Gurbantunggut Desert in China (Zhang et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2011). Eremosparton songoricum grows naturally on bare sand and can tolerate multiple extreme environmental conditions, including drought, high and low temperatures, and UV radiation (Liu et al., 2016, 2017). Eremosparton songoricum has evolved various morphological adaptation strategies to adapt to severe desert water deficit; for example, its leaves are extremely reduced into photosynthetic branches to reduce water loss, and its roots grow horizontally to facilitate cloning propagation so as to optimize water utilization (Liu et al., 2010; Shi et al., 2010). Meanwhile, rapid asexual reproduction expands the inhabited area, which can ameliorate the soil and fix the sand, thus helping protect the habitat. Therefore, E. songoricum is a promising taxon for desertification control and environmental protection (Shi et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2013, 2016). Previous studies at physiological and molecular levels have also shown that E. songoricum is a good model legume for studying the molecular mechanisms of extreme drought stress and identifying genes associated with drought tolerance for crop breeding (Li et al., 2012, 2013, 2014, 2016).

Transcription factors (TFs) play critical roles in gene expression regulation networks in response to various environmental stresses. TFs control downstream genes by binding cis-acting elements in the promoter regions of target genes. Previous research on plant stress tolerance improved through genetic transformation of TF genes has yielded several achievements (Xu et al., 2011). APETALA2/ethylene responsive element binding proteins (AP2/ERF) is one of the largest TF families, and is a key regulator of plant responses to various stresses (Gu et al., 2017; Baillo et al., 2019; Feng et al., 2020). The AP2/ERF family can be divided into five subfamilies, i.e., AP2, DREB, ERF, RAV, and Soloist, according to the type and number of AP2 and B3 conserved domains. AP2 subfamily genes have two AP2 domains that are involved in flower and seed development (Jofuku et al., 1994; Ripoll et al., 2011); ERF and DREB subfamilies have only one AP2 domain, which is the largest gene member among the AP2/ERF family and plays key roles in plant biotic and abiotic stresses (Mizoi et al., 2012). ERF subfamily genes play important roles in plant biotic stress and pathogen responses (Park et al., 2001; Gutterson and Reuber, 2004). DREB subfamily genes are dominant regulators of plant abiotic stress and are prominent during osmotic and cold stress (Agarwal et al., 2006). The RAV subfamily comprises one AP2 domain and one B3 domain, which are involved in floral induction, bud outgrowth, leaf senescence, and responses to pathogen infections and abiotic stresses (Matias-Hernandez et al., 2014). Soloist is a small subfamily of genes possessing a single AP2 domain, but their sequences are highly divergent from those of other AP2/ERF genes (Lakhwani et al., 2016), and they function in plant salt and pathogen responses (Giri et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2016). Many AP2/ERF genes have been isolated from various plants and have been widely used to improve crop stress tolerance (Agarwal et al., 2017; Sarkar et al., 2019).

With the development of high-throughput sequencing, more than 700 plant genomes have been released (Kersey, 2019), which has greatly promoted the identification and functional analysis of AP2/ERF genes. AP2/ERF TFs have been identified on a genome-wide scale in model plants such as Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa (Nakano et al., 2006; Ahmed et al., 2021) and in non-model plants including Vitis vinifera, Brassica rapa, Brassica oleracea, Sesamum indicum, Dimocarpus longan, and Populus trichocarpa (Zhuang et al., 2008; Licausi et al., 2010; Song et al., 2013; Dossa et al., 2016; Li H. et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2020). In legumes, the AP2/ERF family has been identified in Glycine max (Zhang et al., 2008; Jiang et al., 2020), Medicago truncatula (Shu et al., 2016), Cicer arietinum, Cajanus cajan (Agarwal et al., 2016), and Lotus corniculatus (Sun et al., 2014; Cao et al., 2021); however, these results stem from only a small proportion of the thousands of legume species. In addition to the identification results published previously, identification results of AP2/ERF in 36 legumes can be found in the Plant Transcription Factor Database (Plant TFDB 5.0). To date, AP2/ERF gene mining in legume plants is rather limited and not particularly detailed; thus, further research on legume plants and more accurate and detailed identification is required.

We recently sequenced the genome of E. songoricum (China National GeneBank [CNGB], project ID: CNP0002419; 555.67 Mb; 26,442 genes; eight chromosomes). In this study, we first identified AP2/ERF TFs in E. songoricum based on genome data. In total, 153 EsAP2/ERFs, including four subfamilies (AP2, DREB, ERF, and Soloist), were identified, and their detailed classification, gene structure and motif analysis, chromosomal distribution, cis-element analysis, and gene expression patterns under drought stress were examined. Moreover, to better understand the evolution and expansion of AP2/ERFs, we identified and classified the AP2/ERF family in 20 other representative plant species, ranging from algae to angiosperms, including nine other legume plants, to perform a comparative analysis, including subfamily number, ratio, and gene structure characteristics. This is the first study to report genome-wide identification of AP2/ERF family genes in legume shrubs. Our results provide insight into the drought stress mechanisms in legume plants, and we propose candidate genes for drought-resistant plant breeding.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and drought stress treatments

Eremosparton songoricum seeds were collected from the Gurbantunggut Desert Xinjiang province, China (88°24′67′′E, 45°58′11′′N). Seeds were soaked in 98% (v/v) sulfuric acid for 10–15 min to break physical dormancy, after which they were washed with ddH2O and sown on moist filter paper. Seeds were germinated and grown in covered petri dishes under controlled conditions (25°C, 12 h darkness, 100 mol m–2 s–1 light intensity, 60% relative humidity). To each Petri dish (150 mm) containing seeds, 15 mL ddH2O was added every 2 days.

Two-week-old seedlings with similar primary root lengths were transferred to a culture box containing 400 mL PEG6000 (20% w/v) for the drought treatment. For each time point (0, 6, 12, 24, and 36 h), 10 whole plants were harvested, pooled, and rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen for RT-qPCR assay, and samples at 0 h served as controls.

Identification and classification of AP2/ERF genes

A total of 26,442 genes were obtained from E. songoricum genome data. The genome was submitted to CNGB1 under the project ID: CNP0002419. A Hidden Markov model (HMM) scan with PF00847 (AP2 domain) and PF02362 (B3 domain) was used to mine the AP2/ERF gene sequences in E. songoricum and the other 22 plant genomes (Mistry et al., 2021). The profiles were queried using the HMM search command of TBtools-HMMER software (e-value cutoff 1 × 10–3) (Chen et al., 2020). The other 22 plant genomes were downloaded from the NCBI genome2 and Phytozome 13.03 (Goodstein et al., 2011). The AP2 domain of AP2/ERFs with a length of approximately 60 amino acids was considered a full-length AP2 domain protein. All predicted peptide sequences contained at least one complete AP2 domain.

Conserved motif detection and molecular weight, isoelectric point, and subcellular localization prediction in Eremosparton songoricum

The conserved motifs in the AP2/ERF protein sequences were analyzed using the online tool Multiple Expectation Maximization for Motif Elicitation (MEME, version 5.3.3)4 with default parameters (Bailey et al., 2015): only motifs with an e-value under 0.1 were retained for further analysis. Conserved motifs were visualized using the Evolview V3 web tool5 (Subramanian et al., 2019). Molecular weights and isoelectric points of EsAP2/ERFs were predicted using SwissProt-Expasy.6 Subcellular localization analysis was performed using Busca7 (Savojardo et al., 2018).

Multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic analyses

We downloaded 175 Arabidopsis AP2/ERF predicted amino acid sequences from the Plant Transcription Factor Database (PlantTFDB V5.0)8 (Tian et al., 2019). The protein sequences of 153 EsAP2/ERFs from E. songoricum and 175 AtAP2/ERFs from A. thaliana were used to construct phylogenetic trees. Multiple sequence alignment was performed using ClustalW (Thompson et al., 1994), phylogenetic trees were constructed by the neighbor-joining method (with 1,000 bootstrap replicates) using MEGA 11, and evolutionary distances were computed using Poisson correction with pairwise deletion (Tamura et al., 2021). The phylogenetic trees were visualized using Evolview web (Subramanian et al., 2019).

Chromosomal locations, intron-exon structures, and cis-element analysis of AP2/ERF genes

Gene duplication type and Ka/Ks were calculated using the MCSCAN module in TBtools (Chen et al., 2020). Information on chromosome distribution (including chromosome length and the starting positions) was retrieved from the local genome annotation and visualized using Circos module in TBtools (Chen et al., 2020). The intron-exon structures of the AP2/ERF genes were assessed based on the annotation file of 21 plant genomes and were visualized using Evolview web (Subramanian et al., 2019). The 3,000-bp region upstream of the transcriptional start site of 153 EsAP2/ERF genes was used for cis-element site analysis using the PlantCARE website.9

Protein-protein interaction network

The STRING database10 was used to assemble the protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks (Szklarczyk et al., 2021). Based on the annotation of transcriptome and identification in genome, a total of 153 AP2/ERFs and 1,276 other TFs in E. songoricum were used to predict PPI network. The minimum required interaction score was set to medium confidence (0.6). Cytoscape (version 3.8) was used for image processing.

Transcriptome-based expression analysis

Transcriptome data (CNGB, CNP0003150) was used to analysis the expression abundance of 153 EsAP2/ERF genes under drought stress at 0, 6, 12, 24, and 36 h. Three biological replicates were performed. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were determined using FDR < 0.05 and |log2fold change| > 1. TBtools was used to make Heatmap access genes’ relative expression levels.

RT-qPCR assay and data analyses

Total RNA was isolated using the MiniBEST plant RNA kit (Takara, Kyoto, Japan), and first-strand cDNA was synthesized using the PrimeScript™ RT reagent kit (Takara). Twelve EsAP2/ERF genes representative of different subfamilies were selected to explore gene expression patterns. RT-qPCR primers were designed using Primer Premier 5.0, and primer specificities were tested by executing a BLASTn search against local E. songoricum genome data. Primer specificity was further assessed using melting curve analysis of the RT-qPCR. All primers used for RT-qPCR are listed in Supplementary Table 1. RT-qPCR experiments were carried out using the CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, United States) with the SYBR Premix Ex Taq™ kit (Takara). Three biological replicates and three technical replicates of each biological replicate were used for all samples. The RT-qPCR protocol was as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 30 s and 40 cycles of 94°C for 5 s and 60–62°C for 30 s. Gene expression levels were calculated relative to the 0 h timepoint using the 2–ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). The EsEF gene was used to normalize RT-qPCR results (Li et al., 2012).

Statistical analyses were performed, and plots were produced using Graph Pad Prism (version 9.0), and all data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) at 95% confidence level. Differences were tested using the least significant difference multiple comparison test.

Results

Genome-wide identification and classification of AP2/ERFs in Eremosparton songoricum

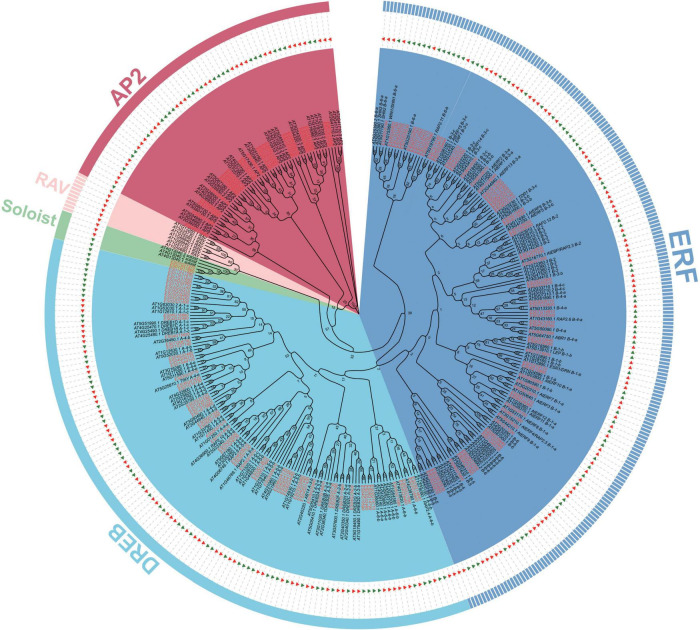

Based on the E. songoricum genome, 153 AP2/ERF genes were identified. A total of 175 AtAP2/ERFs and 153 EsAP2/ERFs were used to construct a phylogenetic tree to classify EsAP2/ERFs. Phylogenetic analyses divided 153 EsAP2/ERF members into four subfamilies: AP2, DREB, ERF, Soloist; RAV subfamily members were not found, based on the genome data (Figure 1). The classification results were confirmed by counting the number of conserved domains (AP2 and B3 domains). Among the confirmed family members, 24 EsAP2/ERFs were assigned to the cluster of the AP2 subfamily based on the phylogenetic tree and presence of the tandemly repeated double AP2 domain (Figure 1). A total of 127 EsAP2/ERFs clustered in the ERF (68 TFs) and DREB (59 TFs) subfamilies, which contained a single AP2 domain. The small Soloist subfamily included two members in E. songoricum (Figure 1). In summary, we identified 24 AP2s, 59 DREBs, 68 ERFs, and two Soloists based on the E. songoricum genome. Considering that some studies reported that transcriptional factors with only one B3 are also considered to belong to the RAV subfamily (Zhao et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2021), we performed a BLASTp search against the E. songoricum genome using the full length of seven Arabidopsis RAVs and 13 soybean RAVs (8 GmRAV only had one B3 domain) as queries, and three hits with high scores were obtained (coverage ≥ 90%; e-value < 1–10; Supplementary Table 2). The predicted protein lengths of 153 EsAP2/ERF members ranged from 110 to 757 amino acids, molecular weight ranged from 12.7 to 86.5 kD, and the protein isoelectric point ranged from 4.4 to 9.8. Most EsAP2/ERFs (88%) were predicted to be located in the nucleus, and two Soloist members were predicted to be localized in the chloroplast (Supplementary Table 3).

FIGURE 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of AP2/ERF genes in Eremosparton songoricum. A neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA 11 with AP2 domains of AtAP2/ERFs and EsAP2/ERFs. The numbers of bootstrap values were based on 1,000 iterations. AP2, DREB, ERF, RAV, Soloist subfamilies are grouped together as indicated in red, cyanine, blue, pink, and green, respectively. EsAP2/ERF are indicated by green triangles and red text, and AtAP2/ERFs are indicated by red triangles and black text.

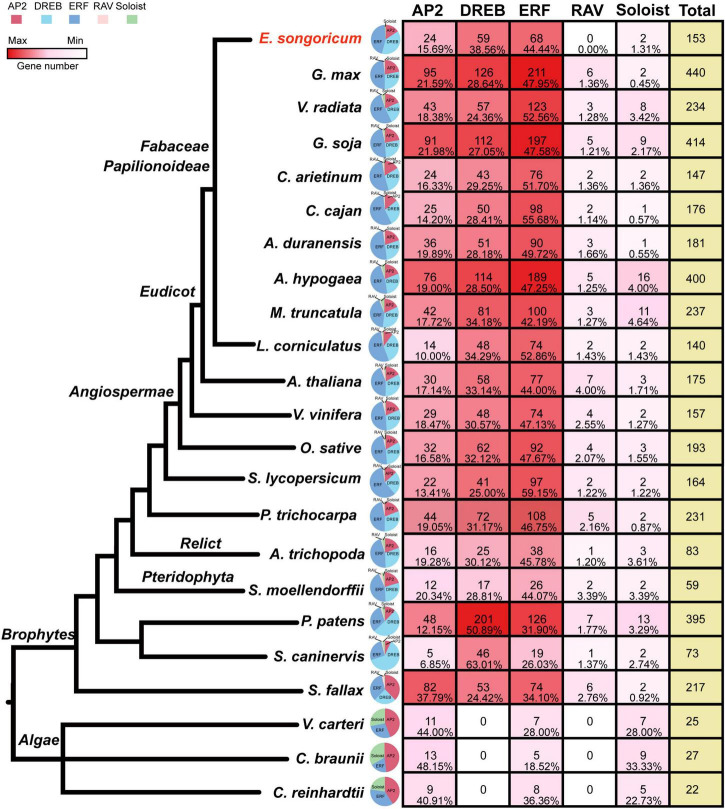

Gene number and ratio comparison analysis of AP2/ERFs in various plants

To better understand the evolution of the AP2/ERF family, in addition to E. songoricum and A. thaliana, we also identified the AP2/ERF family in 21 other representative plants ranging from algae and early land plants to angiosperms, including 10 legume species. We found that in three algae (V. carteri, C. braunii, and C. reinhardtii), only AP2, ERF, and Soloist subfamilies were present. The DREB and RAV subfamily began to occur in mosses (Figure 2), and DREB and ERF subfamilies were consistently represented with numerous members among different plant species, whereas the RAV subfamily retained only few members. The Soloist subfamily represented a large proportion in algae, whereas in land plants it comprised few members.

FIGURE 2.

Classification and gene number/proportion analysis of AP2/ERF family genes in 23 plant species. HMM scan with PF00847 (AP2 domain) and PF02362 (B3 domain) were used to identify AP2/ERF family in 23 species, and the subfamily classification of 22 species were performed by MEGA 11, with 175 AP2/ERF TFs from Arabidopsis thaliana as a reference. The quantity of gene members in different species is shown as a heatmap (see color bar), the maximum is indicated in dark red, the minimum (0) is shown in white. A pie chart shows the ratio of each family, and AP2, DREB, ERF, RAV, Soloist subfamily are shown in red, cyanine, blue, pink, and green, respectively; the numbers and percentage of each subfamily member were shown. The species tree was based on previous literature (Zeng et al., 2014, 2017; Huang et al., 2016).

Among ten legume plants, the other nine representative legume species all contained five subfamilies of AP2/ERF, except for E. songoricum, which lacks a canonical RAV, according to the classic classification method. The number of AP2/ERFs in the ten legumes ranged from 140 (L. corniculatus) to 440 (G. max). The proportion of ERF subfamily genes was higher than that of DREBs, which exceeded 40% in the ten legume plants. The DREB subfamily in E. songoricum was represented at the highest proportion (38.56%) among the ten legumes, followed by L. corniculatus (34.29%), and M. truncatula (34.18%). The ratio of the RAV subfamily was <2%, and the numbers of genes ranged from 2 to 6 (Figure 2), Soloist gene numbers varied among legumes, ranging from 1 (C. cajan and A. duranensis) to 16 (A. hypogaea).

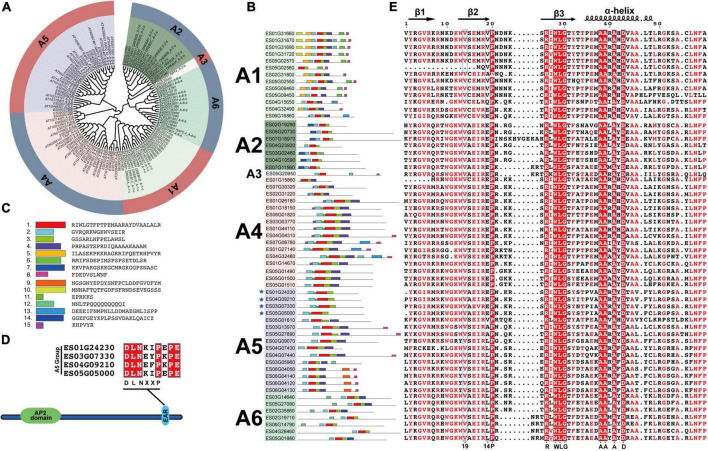

Detailed classification of the EsDREB subfamily

The DREB subfamily plays key roles in plant abiotic stress responses and can be further divided into A1–A6 groups. In the present study, 59 EsDREBs were classified into 6 groups by constructing a phylogenetic tree with DREBs of A. thaliana. There were 13, 7, 1, 16, 15, and 7 members in the A1–A6 groups of EsDREBs, respectively (Figure 3A). Fifteen conserved motifs were detected in the protein sequence of the EsDREBs (Figures 3B,C). Motifs 1, 2, and 3 were composed of the AP2 domain, of which motif 1 contained the β3 sheet and α-helix, motif 2 contained β1 and β2 sheets of the AP2 domain; motif 3 represented the C-terminal of the AP2 domain. Other motifs were divergent among different groups, such as motif 10 and motif 5 which occurred only in the A1 group; motif 7 was specific to the A2 group, whereas the EAR repressor motif was detected in the C-terminus of four A-5 type EsDREBs (Figure 3D). Multiple sequence alignment analysis of the AP2 domain showed that EsDREBs shared significant amino acid similarity; 9 out of the 59 amino acids in AP2 domains, including the residues 20-P, 26-R, 28-W, 29-L, 30-G, 38-A, 39-A, 41-A, and 43-D, were completely conserved among all EsDREBs (Figure 3D). In addition, consistent with other plant DREBs, the 14th V residue was completely conserved among all EsDREB members except ES05G02560 which lacks some amino acids in the N-terminal region, while the 19th amino acid had multiple patterns, including E/V/L/A/Q (Figure 3E).

FIGURE 3.

Classification and sequence analysis of EsDREBs subfamily. The phylogenetic tree was constructed based on AP2 domains of AtDREBs and EsDREBs using MEGA 11 with the neighbor-joining method. 15 motifs were observed using the MEME webtool. The AP2 domains of 59 EsDREBs were used to perform multiple sequence alignment. (A) Phylogenetic tree of EsDREB subfamily. (B) Motif distributions in A1–A6 group of EsDREBs. (C) Amino acid sequence of each motif. Genes with EAR motif are indicated by stars (D) EsDREB genes with EAR motif. (E) Multiple sequence alignment of AP2 domains of EsDREBs.

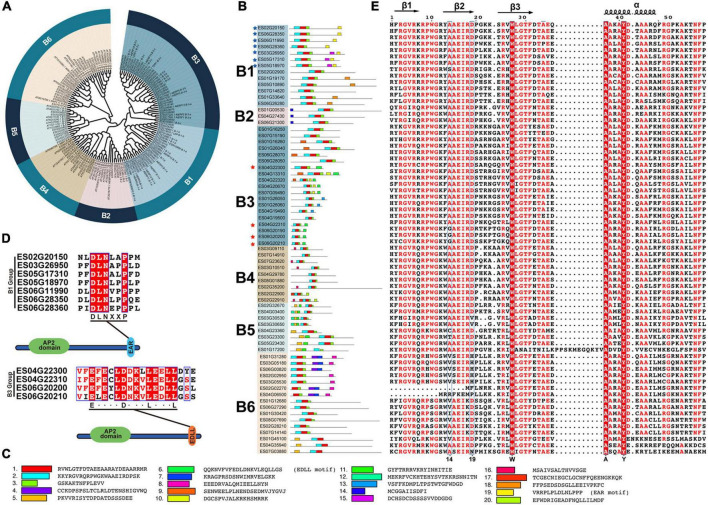

Detailed classification of the EsERF subfamily

EsERF subfamily can be further classified into six groups (Figure 4A). A total of 13, 3, 19, 9, 8, and 16 EsDREBs were identified for B1–B6, respectively (Figures 4A,B). In total, 20 motifs in 68 EsERF proteins were observed, of which motif 2 contained β1 and β2 sheets, motif 1 was composed of β3 and an α-helix, and motif 3 was the C-terminus of the AP2 domain. Furthermore, ERFs in the same group mostly shared a similar motif composition in addition to the AP2 domain; for example, motif 14 was shared among the B2 group, motif 16 was unique to the B4 group, and motif 5 was only present in the B5 group. The transcription repressor and activator motifs EAR (motif 19) and EDLL (motif 6) occurred at the C-end of B1 and B3 EsDREBs, respectively, and four B3 EsDREBs had EDLL motifs, which were distributed in seven B1 EsDREB members (Figures 4B–D). Three out of the 59 amino acid residues, including 27-W, 37-A and 41-Y, which occurred in the β3 sheet and α-helix of all EsERFs, were completely conserved (Figure 4E). The 14th and 19th conserved amino acids were diverse among ERFs, and the patterns of the 14th and 19th position of AP2 domains were A14 and D19 in most EsERFs, while the 14th position also showed a G/V/I/T/C pattern, and the 19th position was changed to H or N in some EsERFs. The AEIR located between the 14th and 19th position was the same in B1–B5, while the four amino acids changed to SEIR or AEIR/K in B6 group EsERFs (Figure 4E).

FIGURE 4.

Classification and sequence analysis of EsERFs subfamily. The phylogenetic tree was constructed based on AP2 domain sequence of AtERFs and EsERFs using MEGA 11 with neighbor-joining; 25 motifs were discovered using MEME online tools. AP2 domains were used for multiple sequence alignment. (A) Phylogenetic tree of the EsERF subfamily. (B) Motif distribution in B1–B6 groups of EsERFs, genes with EAR or EDLL motif are indicated by blue and red stars, respectively. (C) Amino acid sequence of each motif. (D) Genes with EAR motif and EDLL motifs. (E) Multiple sequence alignment of AP2 domains of EsERFs.

Gene structure analysis of AP2/ERFs in Eremosparton songoricum and other plants

To gain insights into gene structural diversity, we examined the exon and intron organization of EsAP2/ERF genes. In E. songoricum, the proportions of genes with introns in the DREB, ERF, AP2, and Soloist subfamilies were 11.9, 35.3, 100, and 100%, respectively. All members of EsAP2 (24/24) and EsSoloist (2/2) had five to ten introns in the AP2 subfamily and five to six in the Soloists subfamily (Figure 5). For the ERF subfamily, 24 of 68 EsERFs had introns; among them, 19 EsERFs had only a single intron, four EsERFs had two introns, and one EsERF (ES02G35200) belonging to the B4 group had seven introns, which also had the longest gene length. For the DREB subfamily, only 7 out of 59 EsDREB members had introns (N = 1–2); 6 of 7 EsDREBs only had a single intron, and the remaining one had two introns (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Gene structure analysis of 153 EsAP2/ERF genes. Intron-exon structures were constructed by gene annotation. Panels (A–D) show AP2, ERF, Soloist, and DREB subfamilies, respectively. Light green and gray indicate exons and introns, respectively.

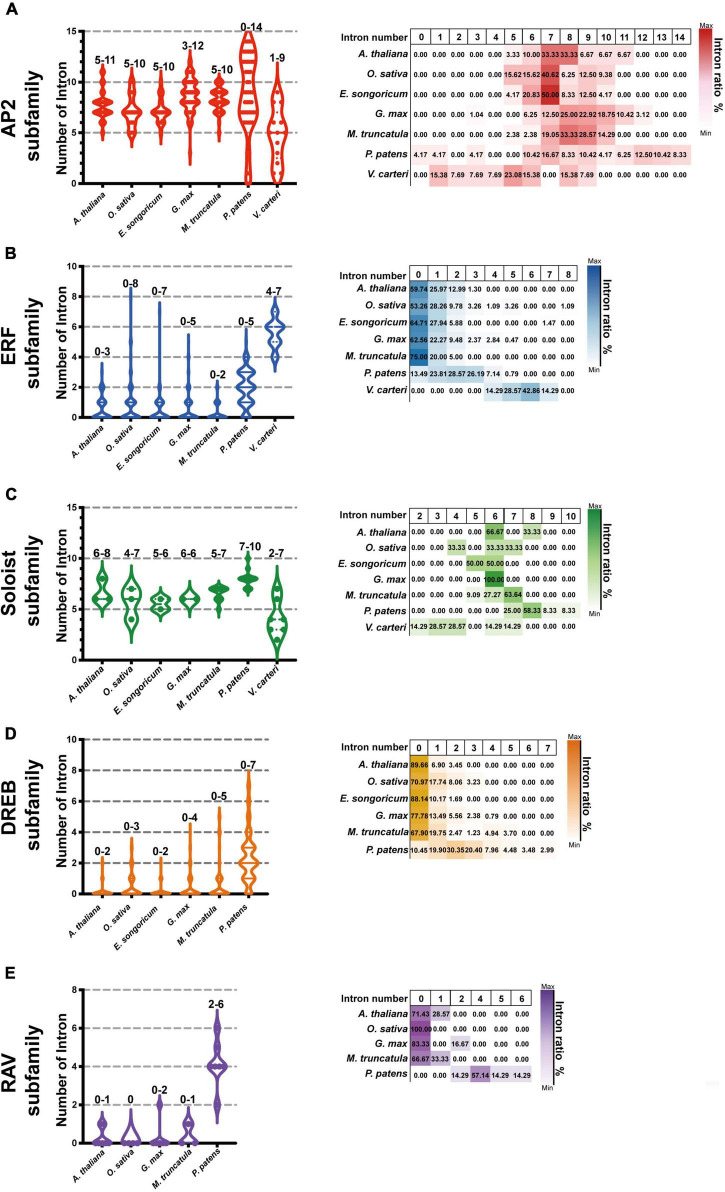

We further selected six model plants, including G. max, M. truncatula, A. thaliana, O. sativa, P. patens, and V. carteri, to perform intron-exon distribution comparisons of AP2/ERFs (Supplementary Figures 1–6). Similar to E. songoricum, almost all genes belonging to the AP2 and Soloist subfamilies in other plant species had introns, while most DREB and ERF genes were without intron (Figure 6 and Supplementary Figures 1–6). Overall, the intron number distribution of five subfamilies in algae (V. carteri) and moss (P. patens) was more dispersed than in angiosperms. Specifically, for the AP2 subfamily, except for P. patens (4.17% of PpAP2s were intronless), the other six species all had introns (mainly seven to nine) (Figure 6A); however, regarding the ERF subfamily, most ERFs in angiosperm plants lack introns, and the intron number centered at 2 (Figure 6B); a similar intron-exon distribution pattern was found in DREB subfamilies (Figure 6D). For Soloist subfamilies, except for V. carteri (14.29%), Soloists in other species all had introns (mainly six to seven; Figure 6C). A large majority of RAVs in angiosperms were intronless, whereas PpRAVs had two to six introns.

FIGURE 6.

Intron-exon number analysis of EsAP2/ERFs in seven plant species. The genome annotation of seven species including G. max and M. truncatula, Arabidopsis, O. sativa, P. patens, and V. carteri were used to investigate AP2/ERF family intron distribution. Graph pad prism 9 was used to produce box and violin plots; 153 EsAP2/ERF, 440 GmAP2/ERF, 237 MtAP2/ERF, 175 AtAP2/ERF, 193 OsAP2/ERF, 395 PpAP2/ERF, and 25 VcAP2/ERF genes were used for intron-exon distribution analysis. Panels (A–C) show intron numbers of AP2, ERF, and Soloist subfamily members of introns of seven plant species. The DREB and RAV subfamilies have not evolved in V. carteri, and Eremosparton songoricum does not contain the canonical RAV subfamily; thus, panel (D) shown are intron numbers and proportions of DREB subfamily from six species (excluding V. carteri). Panel (E) intron numbers of five species and proportions in the RAV subfamily (excluding V. carteri and E. songoricum). The intron number range is indicated on top of each column. The violin plots show intron member distribution, and the heatmap (right) shows gene proportions with different intron numbers as indicated by coloration.

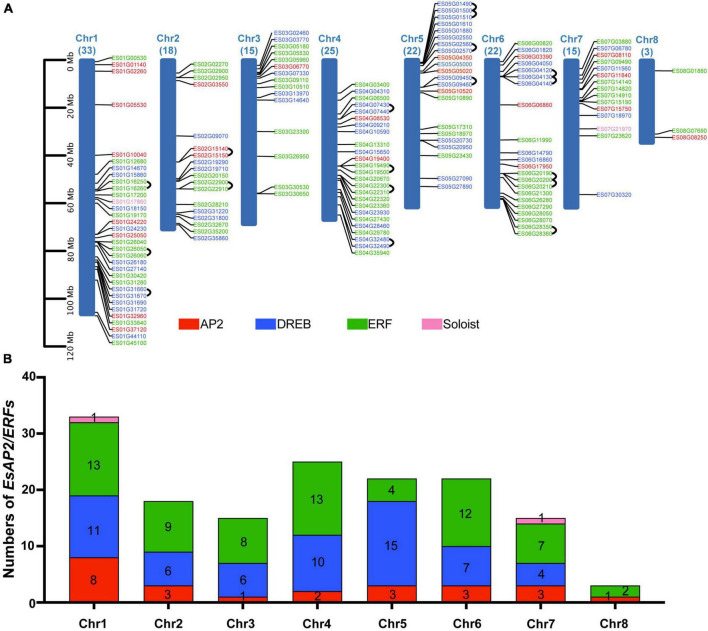

Chromosomal distribution and duplication analysis of EsAP2/ERF

Chromosome mapping analysis indicated that 153 AP2/ERF genes were unevenly mapped on eight chromosomes in E. songoricum. Each chromosome contained at least three EsAP2/ERF genes. Chromosome 1 contained the largest number (33 genes) of EsAP2/ERF genes, followed by chromosomes 4 (25 genes), 5 (22 genes), and 6 (22 genes), whereas chromosome 8 contained only three EsAP2/ERFs with two ERFs and one AP2 gene (Figure 7A). Members of the AP2 and ERF subfamilies were widely distributed across all chromosomes. DREB genes did not occur on chromosome 8, whereas two Soloist genes were located on chromosomes 1 and 7. Chromosome 1 had 13 ERFs, 11 DREBs, 8 AP2s, and one Soloist; chromosome 5 had the largest number of DREB genes (15); chromosomes 1 and 4 had the largest number of ERFs (13) (Figure 7B). In order to elucidate the duplication mechanism of the EsAP2/ERF family, the gene replication types were analyzed using MCScanX, and the results are shown in Supplementary Table 4. A total of 150 duplication events were found, including 71 segmental or WGD (Whole Genome Duplication), 46 dispersed, 27 tandem, and six proximal duplication events. Furthermore, 15 link gene pairs were found on chromosomes 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 (Figure 7A). The Ka/Ks values of the 15 link gene pairs were all <1, indicating that they evolved under the pressure of purifying selection (Supplementary Table 5).

FIGURE 7.

EsAP2/ERF gene distribution and tandem duplication, in eight chromosomes of Eremosparton songoricum. BLASTp and gene location information was used to determine gene duplication. (A) Chromosome distribution analysis of EsAP2/ERFs, chromosome size is indicated by relative length. The total gene numbers of EsAP2/ERFs are shown on the top of each chromosome. AP2, DREB, ERF, and Soloist genes are indicated in red, blue, green, and pink, respectively. Black loops indicate duplication gene link pairs. (B) Distribution numbers of four subfamily genes of EsAP2/ERFs in eight chromosomes.

The cis-regulatory elements and protein-protein interaction analysis of EsAP2/ERFs

Transcription factors play key roles in regulating gene expression by interacting with cis-acting elements (Nakashima et al., 2009). To understand the putative function of EsAP2/ERF genes in plant stress responses and the regulatory relationship with plant hormones, we analyzed cis-elements of 3,000 bp of promoter regions of 153 EsAP2/ERF genes. A total of 116 cis-elements were found, including six unnamed and 110 reported elements that were involved in distinct biological functions (Supplementary Table 6). We selected 36 classic previously reported cis-elements (Chai and Subudhi, 2016; Shi et al., 2019; Li et al., 2021) belonging to 22 categories and divided them into two major functional categories, i.e., phytohormone-responsive and abiotic or biotic stress-related (Supplementary Figure 7 and Supplementary Tables 7, 8). The 22 categories occurred 4,496 times in the promoter region of 153 EsAP2/ERF genes, among which MYB, MYC, and ABRE elements were the most enriched (Supplementary Figure 7). Specifically, 99% of the EsAP2/ERF genes contained MYB and MYC binding sites that appeared 1,085 and 620 times, representing 37 and 21% of the abiotic and biotic stress-related cis-elements, respectively (Supplementary Table 7). The ABRE and ERE, involved in ABA and ET responses, were found 541 and 260 times in 110 and 107 EsAP2/ERF genes, respectively, and accounted for 52% of the phytohormone-responsive genes (Supplementary Table 7). Moreover, GA-responsive elements (GARE, P-box, and TATC-box), JA-responsive elements (CGTCA motif, TGACG motif), SA-responsive elements (TCA-element), and auxin-responsive elements (TGA, AuxRR) were present in 122, 110, 102, and 76 EsAP2/ERF genes, respectively (Supplementary Figure 7).

To identify potential interacting proteins with the AP2/ERF transcription factors, a protein - protein interaction (PPI) network was generated with the STRING database (Szklarczyk et al., 2021). A total of 49 EsAP2/ERFs including 23 EsERFs, 19 EsDREBs, 6 EsAP2s, one EsSoloist interacted with 160 other TFs in the network (Supplementary Figure 8 and Supplementary Table 9), in which EsDREBs had the largest number of interacted TFs, then followed by EsERFs. EsAP2/ERFs mainly interacted with WRKYs (17), HSFs (14), MYBs (11), STZs (9), and ABFs (8). The A2 type of DREB (ES02G19290) directly interacted with other 20 TFs, such as ABI5 and ABFs. AP2 (ES04G19400) and Soloist (ES01G17860) only interacted with members of EsAP2/ERFs.

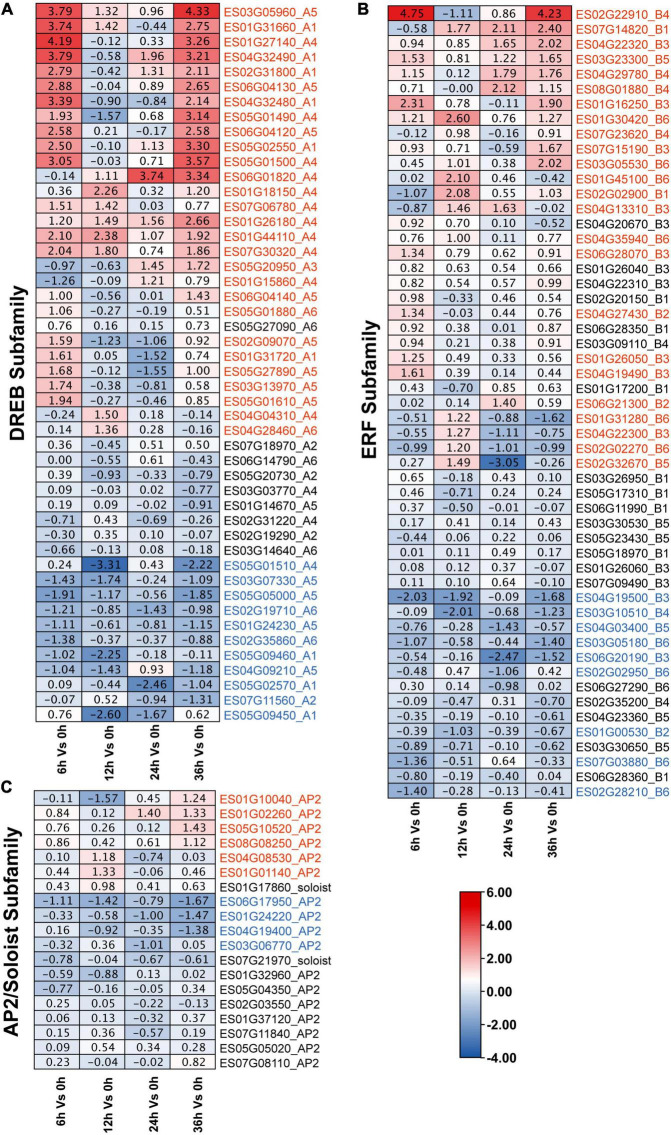

Expression patterns of EsAP2/ERF genes in response to drought stress

To further determine the involvement of EsAP2/ERF genes in response to drought stress, we analyzed the expression pattern of EsAP2/ERF based on transcriptome data (CNP0003150). As a result, a total of 120 EsAP2/ERF genes were quantified by mapping reads among 153 EsAP2/ERFs (120/153, 78.43%), which contained 53 ERFs, 48 DREBs, 17 AP2s, and 2 Soloists. Eighty-one differentially expressed EsAP2/ERFs genes included 32 ERFs (32/53, 60.4%), 39 DREBs (39/48, 81.2%) and 10 AP2s (10/17, 58.8%). Differentially expressed EsAP2/ERFs were mainly distributed at 6 and 36 h, included 37 and 34 genes, respectively, and notably more EsAP2/ERF genes were up-regulated than down-regulated (75/32) (Supplementary Figure 9). Differentially expressed EsDREBs included 28 up-regulated and 11 down-regulated genes, respectively (Figure 8A). Up-regulated DREB genes consisted of A1, A4, and A5 group, most of genes significantly up-regulated at 6 and 36 h, among them, A4 (ES01G27140) and A5 (ES03G05960) had the highest expression with more than 16-fold (converted by |Log2 FC|) increase compared with that at 0 h. Differentially expressed EsERFs included 23 up-regulated and nine down-regulated genes, respectively (Figure 8B), of which ES02G22910 (B4 type of ERF) had the highest expression with more than 16-fold (converted by |Log2 FC|) increase compared with that at 0 h. EsSoloist and EsAP2 subfamily genes were slight induced after drought stress (Figure 8C).

FIGURE 8.

Expression profiles of 120 EsAP2/ERF genes response to drought stress based on RNA-seq data. Expression profiles (in |log2fold change| values) of the (A) DREB; (B) ERF; and (C) AP2 and Soloist subfamily, respectively. Up-regulated genes were marked by red, down-regulated genes were marked by blue.

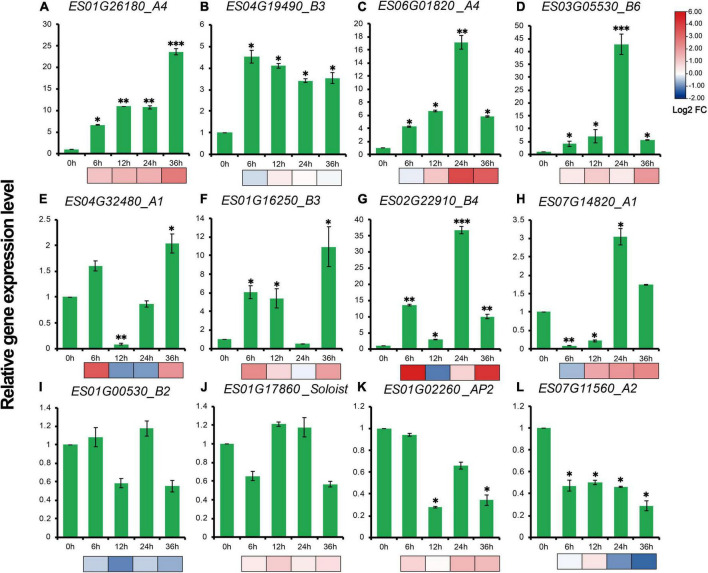

RT-qPCR results showed that expression profiles of 12 genes, representative of different family members of EsAP2/ERFs including five DREBs, five ERFs, one AP2 and one Soloist demonstrated diverse gene expression patterns during drought stress treatment. The expression patterns of most selected genes were consistent with the transcriptome results (Figure 9). Eight out of twelve genes were strongly up-regulated in drought stress-treated E. songoricum, which highly elevated and reached the peak at 24 or 36 h (Figures 9A–H). Similar like RNA-Seq results, ES03G05530 and ES02G22910 also were strongly induced with drought stress and increased almost 40-fold compared with that at 0 h (Figures 9D,G). Two genes including B2 type of ERF (ES01G00530) and Soloist (ES01G17860) were slightly changed (Figures 9I,J), and two genes (ES01G02260 and ES07G11560) exhibited a decline pattern after drought stress (Figures 9K,L).

FIGURE 9.

(A–L) Gene expression levels of 12 EsAP2/ERF genes under drought treatment. The gene expression levels were calculated relative to 0 h using the 2–ΔΔCt method. Shown are the mean values ± SE of three replicates, and the significance level relative to controls is *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

Detailed identification and classification of EsAP2/ERFs in a desert legume

The AP2/ERF gene family is one of the largest groups of TFs in plants, and it is characterized by at least one AP2 domain, which plays important roles in plant development and stress responses (Sakuma et al., 2002; Nakano et al., 2006; Agarwal et al., 2017). In the current study, genome-wide analysis of the AP2/ERF gene family from the desert legume E. songoricum was conducted, and 153 putative AP2/ERF genes were identified. These 153 genes covered the AP2, ERF, Soloist, and DREB subfamilies based on domain numbers and sequence similarities. The classic RAV gene nomenclature is characterized by the presence of a C-terminal B3 domain and N-terminal AP2 domain (Kagaya et al., 1999). In the present study, we were unable to identify a canonical RAV protein containing both B3 and AP2 domains; however, the other nine legume plants all had canonical RAV genes (N = 2–6; Figure 2). Previous studies on soybean and rice introduced a classification method with BLASTp searching using AtRAVs protein sequence as query, and genes with only one B3 domain were also considered to be the RAV genes (Zhao et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2021), it is worth noting that these GmRAVs showed different expression patterns under abiotic stresses compared with canonical GmRAVs, implying that they may have different functions. Using this method, we obtained three hits that were probably RAV proteins (Supplementary Table 4); however, further evidence is needed to confirm whether those candidates were EsRAVs. The classification results obtained from the phylogenetic tree and conserved domain numbers were in accordance with the motif and amino acid composition patterns, suggesting that the conserved motifs and amino acid sites can be helpful in classifying the specific subfamily/group of AP2/ERF (Shu et al., 2016; Li X. et al., 2017, Li et al., 2018). Moreover, we found that genes belonging to the same subfamily or specific group shared similar intron-exon organization, which has also been reported in other species (Song et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2022), indicating that intron-exon structure can also be a useful basis for AP2/ERF family classification.

Origination and evolution of AP2/ERFs

To explore the origin and evolution of the AP2/ERF gene family in plants, we identified AP2/ERF family genes in 22 other representative plant species ranging from algae to land plants and compared the gene numbers and structures across these 21 plants. Consistent with previous studies, AP2 and ERF already existed in algae, whereas RAV and DREB began to appear in mosses (Mizoi et al., 2012; Song et al., 2016). Our results also supported the phenomenon that DREB and ERF occurred at a large proportion, whereas Soloist and RAV were small subfamilies with very few genes in land plants (Agarwal et al., 2016; Shu et al., 2016; Li X. et al., 2017, Li et al., 2018). In the 10 legume species, the number of AP2/ERFs varied from 140 to 440, and G. max had the largest number of AP2/ERF genes, followed by G. soja and A. hypogaea, which can be explained by independent whole-genome duplications at the species level (Liu et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2021). Notably, the number of DREB genes in E. songoricum accounted for the highest proportion among the ten legume species, which can be partially explained by the adaptation of E. songoricum to harsh desert environments.

It is known that ancestral species have intron-rich genes, and most plant species experienced extensive loss or insertion of introns due to selective pressure (Roy and Penny, 2007; Rogozin et al., 2012). Low intron gain rates and intron number reduction are common in eukaryotic evolution (Roy and Penny, 2006, 2007). In the current study, we selected seven representative species ranging from algae and land plants to compare AP2/ERF gene structures. Our results showed that almost all AP2 and Soloist subfamily genes of E. songoricum and other plant species had introns, whereas most DREB, ERF, and RAV genes were intronless (Figure 6). Angiosperms such as Arabidopsis, E. songoricum, and O. sativa shared the same intron-exon structures, whereas the number of introns in algae and moss was more variable than in angiosperms. These results are consistent with the intro-exon evolution patterns of AP2/ERF genes of various higher species (Dossa et al., 2016; Zeng et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2020; Ahmed et al., 2021; Cao et al., 2021).

AP2/ERF family genes play important roles in Eremosparton songoricum stress responses

AP2/ERF genes play important roles in plant abiotic and biotic stress responses, especially in the DREB subfamily which exerts important effects under different abiotic stress conditions, including drought, heat, and salt stress (Sakuma et al., 2002; Shi et al., 2019). Eremosparton songoricum is an extremely drought-tolerant legume species; hence, it is a good material for stress-tolerance gene isolation (Li et al., 2014). Cis element analysis showed that all EsAP2/ERF genes were enriched in ABRE, MYB, and MYC cis-elements, suggesting that EsAP2/ERF genes may participate in the regulation of abiotic and biotic stress responses and plant hormone transduction pathways. Classification results of the EsAP2/ERF gene family showed that DREB genes had the largest proportion, compared to the other nine legume plants, indicating the evolutionary expansion of DREBs for adaptation to harsh desert environments. We previously cloned a DREB2 gene from E. songoricum, which was associated with strong resistance to drought, salinity, cold, and heat (Li et al., 2014, 2016). Moreover, EsDREBs had the largest number of differentially expressed genes and were highly induced in response to drought (39/48, 81.3%), in which 28 EsDREBs genes were significantly upregulated in response to drought stress, ES01G27140 and ES03G05960 were strongly increased by more than 16-fold compared to normal condition (Figure 8A). Meanwhile, EsERFs also remarkably increased after drought stress (Figures 8B,C, 9), indicating that EsDREBs/EsERFs play important roles in E. songoricum response to drought stress and they are good stress tolerance genes for further functional verification.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary material.

Author contributions

XL conceived the ideas and designed the study. MZ collected and analyzed the data. SQ performed the experiments. MZ and YL wrote the manuscript. XL, DZ, YH, and BG revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Footnotes

Funding

This work was supported by the Third Xinjiang Scientific Expedition Program (Grant No. 2021xjkk0500), Key Research Program of Frontier Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. ZDBS-LY-SM009), Youth Innovation Promotion Association of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No.2018478).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2022.885694/full#supplementary-material

References

- Agarwal G., Garg V., Kudapa H., Doddamani D., Pazhamala L. T., Khan A. W., et al. (2016). Genome-wide dissection of AP2/ERF and HSP90 gene families in five legumes and expression profiles in chickpea and pigeonpea. Plant Biotechnol. J. 14 1563–1577. 10.1111/pbi.12520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal P. K., Agarwal P., Reddy M. K., Sopory S. K. (2006). Role of DREB transcription factors in abiotic and biotic stress tolerance in plants. Plant Cell Rep. 25 1263–1274. 10.1007/s00299-006-0204-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal P. K., Kapil G., Sergiy L., Parinita A. (2017). Dehydration responsive element binding transcription factors and their applications for the engineering of stress tolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 68 2135–2148. 10.1093/jxb/erx118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed S., Rashid M. A. R., Zafar S. A., Azhar M. T., Waqas M., Uzair M., et al. (2021). Genome-wide investigation and expression analysis of APETALA-2 transcription factor subfamily reveals its evolution, expansion and regulatory role in abiotic stress responses in Indica Rice (Oryza sativa L. ssp. indica). Genomics 113 1029–1043. 10.1016/j.ygeno.2020.10.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey T. L., Johnson J., Grant C. E., Noble W. S. (2015). The MEME Suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 43 W39–W49. 10.1093/nar/gkv416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baillo E. H., Kimotho R. N., Zhang Z., Xu P. (2019). Transcription factors associated with abiotic and niotic stress tolerance and their potential for crops improvement. Genes 10:771. 10.3390/genes10100771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao D., Lin Z., Huang L., Damaris R. N., Yang P. (2021). Genome-wide analysis of AP2/ERF superfamily in lotus (Nelumbo nucifera) and the association between NnADAP and rhizome morphology. BMC Genomics 22:171. 10.1186/s12864-021-07473-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai C., Subudhi P. K. (2016). Comprehensive analysis and expression profiling of the OsLAX and OsABCB auxin transporter gene families in Rice (Oryza sativa) under phytohormone stimuli and abiotic stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 7:593. 10.3389/fpls.2016.00593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Chen H., Zhang Y., Thomas H. R., Frank M. H., He Y., et al. (2020). TBtools: An integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant 13 1194–1202. 10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Li Y., Zhang H., Ma Q., Wei Z., Chen J., et al. (2021). Genome-wide analysis of the RAV transcription factor genes in Rice reveals their response patterns to hormones and virus infection. Viruses 13:752. 10.3390/v13050752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dossa K., Wei X., Li D., Fonceka D., Zhang Y., Wang L., et al. (2016). Insight into the AP2/ERF transcription factor superfamily in sesame and expression profiling of DREB subfamily under drought stress. BMC Plant Biol. 16:171. 10.1186/s12870-016-0859-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng K., Hou X. L., Xing G. M., Liu J. X., Duan A. Q., Xu Z. S., et al. (2020). Advances in AP2/ERF super-family transcription factors in plant. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 40 750–776. 10.1080/07388551.2020.1768509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giri M. K., Swain S., Gautam J. K., Singh S., Singh N., Bhattacharjee L., et al. (2014). The Arabidopsis thaliana At4g13040 gene, a unique member of the AP2/EREBP family, is a positive regulator for salicylic acid accumulation and basal defense against bacterial pathogens. J. Plant Physiol. 171 860–867. 10.1016/j.jplph.2013.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodstein D. M., Shu S., Howson R., Neupane R., Hayes R. D., Fazo J., et al. (2011). Phytozome: A comparative platform for green plant genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 40 D1178–D1186. 10.1093/nar/gkr944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu C., Guo Z., Hao P., Wang G., Jin Z., Zhang S. (2017). Multiple regulatory roles of AP2/ERF transcription factor in angiosperm. Bot. Stud. 58:6. 10.1186/s40529-016-0159-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutterson N., Reuber T. L. (2004). Regulation of disease resistance pathways by AP2/ERF transcription factors. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 7 465–471. 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C.-H., Sun R., Hu Y., Zeng L., Zhang N., Cai L., et al. (2016). Resolution of Brassicaceae phylogeny using nuclear genes uncovers nested radiations and supports convergent morphological evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33 394–412. 10.1093/molbev/msv226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W., Zhang X., Song X., Yang J., Pang Y. (2020). Genome-wide identification and characterization of APETALA2/Ethylene-Responsive element binding factor superfamily genes in soybean seed development. Front. Plant Sci. 11:566647. 10.3389/fpls.2020.566647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jofuku K. D., Denboer B. G. W., Vanmontagu M., Okamuro J. K. (1994). Control of Arabidopsis flower and seed development by the homeotic gene APETALA2. Plant Cell 6 1211–1225. 10.2307/3869820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagaya Y., Ohmiya K., Hattori T. (1999). RAV1, a novel DNA-binding protein, binds to bipartite recognition sequence through two distinct DNA-binding domains uniquely found in higher plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 27 470–478. 10.1093/nar/27.2.470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersey P. J. (2019). Plant genome sequences: Past, present, future. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 48 1–8. 10.1016/j.pbi.2018.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakhwani D., Pandey A., Dhar Y. V., Bag S. K., Trivedi P. K., Asif M. H. (2016). Genome-wide analysis of the AP2/ERF family in Musa species reveals divergence and neofunctionalisation during evolution. Sci. Rep. 6 18878–18895. 10.1038/srep18878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamaoui M., Jemo M., Datla R., Bekkaoui F. (2018). Heat and drought stresses in crops and approaches for their mitigation. Front. Chem. 6:26. 10.3389/fchem.2018.00026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Li X., Zhang D., Liu H., Guan K. (2013). Effects of drought stress on the seed germination and early seeding growth of the endemic desert plant Eremosparton Songoricum (FABACEAE). Excli J. 12 89–101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Wang Y., Wu M., Li L., Li C., Han Z., et al. (2017). Genome-Wide identification of AP2/ERF transcription factors in Cauliflower and expression profiling of the ERF Family under salt and drought Stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 8:946. 10.3389/fpls.2017.00946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Li X., Yang H., Zhang D. (2016). Analysis on stress-resistant functions of EsDREB2B gene from Eremosparton songoricum in Tobacco. Mol. Plant Breed. 14 302–308. [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Geng Z., Zhang C., Wang K., Jiang X. (2021). Whole-genome characterization of Rosa chinensis AP2/ERF transcription factors and analysis of negative regulator RcDREB2B in Arabidopsis. BMC Genomics 22:90. 10.1186/s12864-021-07396-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Gao B., Zhang D., Liang Y., Liu X., Zhao J., et al. (2018). Identification, classification, and functional analysis of AP2/ERF Family genes in the desert moss Bryum argenteum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19 3637–3654. 10.3390/ijms19113637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Yang H., Zhang D., Zhang Y., Wood A. J. (2012). Reference gene selection in the desert plant Eremosparton songoricum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 13 6944–6963. 10.3390/ijms13066944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Zhang D., Gao B., Liang Y., Yang H., Wang Y., et al. (2017). Transcriptome-Wide identification, classification, and characterization of AP2/ERF family genes in the desert moss Syntrichia caninervis. Front. Plant Sci. 8:262. 10.3389/fpls.2017.00262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Zhang D., Li H., Wang Y., Zhang Y., Wood A. J. (2014). EsDREB2B, a novel truncated DREB2-type transcription factor in the desert legume Eremosparton songoricum, enhances tolerance to multiple abiotic stresses in yeast and transgenic tobacco. BMC Plant Biol. 14:44. 10.1186/1471-2229-14-44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licausi F., Giorgi F. M., Zenoni S., Osti F., Pezzotti M., Perata P. (2010). Genomic and transcriptomic analysis of the AP2/ERF superfamily in Vitis vinifera. BMC Genomics 11:719. 10.1186/1471-2164-11-719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Abudureheman B., Baskin J., Baskin C., Zhang D. (2016). Seed development in the rare cold desert sand dune shrub Eremosparton songoricum and a comparison with other papilionoid legumes. Plant Species Biol. 31 169–177. 10.1111/1442-1984.12098 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Abudureheman B., Zhang L., Baskin J. M., Baskin C. C., Zhang D. (2017). Seed dormancy-breaking in a cold desert shrub in relation to sand temperature and moisture. AoB Plants 9:plx003. 10.1093/aobpla/plx003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Shi X., Wang J., Yin L., Huang Z., Zhang D. (2011). Effects of sand burial, soil water content and distribution pattern of seeds in sand on seed germination and seedling survival of Eremosparton songoricum (Fabaceae), a rare species inhabiting the moving sand dunes of the Gurbantunggut Desert of China. Plant Soil 345 69–87. 10.1007/s11104-011-0761-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Tao Y., Qiu D., Zhang D., Zhang Y. (2013). Effects of artificial sand fixing on community characteristics of a rare desert shrub. Conserv. Biol. 27 1011–1019. 10.1111/cobi.12084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Du H., Li P., Shen Y., Peng H., Liu S., et al. (2020). Pan-Genome of wild and cultivated Soybeans. Cell 182 162–176.e13. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Zhang D., Yang H., Liu M., Shi X. (2010). Fine-scale genetic structure of Eremosparton songoricum and implication for conservation. J. Arid Land 2 26–32. 10.3724/sp.J.1227.2010.00026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(T)(−Delta Delta C) method. Methods 25 402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matias-Hernandez L., Aguilar-Jaramillo A. E., Marin-Gonzalez E., Suarez-Lopez P., Pelaz S. (2014). RAV genes: Regulation of floral induction and beyond. Ann. Bot. 114 1459–1470. 10.1093/aob/mcu069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mistry J., Chuguransky S., Williams L., Qureshi M., Salazar G. A., Sonnhammer E. L. L., et al. (2021). Pfam: The protein families database in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 49 D412–D419. 10.1093/nar/gkaa913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizoi J., Shinozaki K., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. (2012). AP2/ERF family transcription factors in plant abiotic stress responses. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Regul. Mech. 1819 86–96. 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano T., Suzuki K., Fujimura T., Shinshi H. (2006). Genome-wide analysis of the ERF gene family in Arabidopsis and rice. Plant Physiol. 140 411–432. 10.1104/pp.105.073783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima K., Ito Y., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. (2009). Transcriptional regulatory networks in response to abiotic stresses in Arabidopsis and Grasses. Plant Physiol. 149 88–95. 10.1104/pp.108.129791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J. M., Park C. J., Lee S. B., Ham B. K., Shin R., Paek K. H. (2001). Overexpression of the tobacco Tsi1 gene encoding an EREBP/AP2-Type transcription factor enhances resistance against pathogen attack and osmotic stress in tobacco. Plant Cell 13 1035–1046. 10.1105/tpc.13.5.1035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priya M., Dhanker O. P., Siddique K. H. M., HanumanthaRao B., Nair R. M., Pandey S., et al. (2019). Drought and heat stress-related proteins: An update about their functional relevance in imparting stress tolerance in agricultural crops. Theor. Appl. Genet. 132 1607–1638. 10.1007/s00122-019-03331-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripoll J. J., Roeder A. H. K., Ditta G. S., Yanofsky M. F. (2011). A novel role for the floral homeotic gene APETALA2 during Arabidopsis fruit development. Development 138 5167–5176. 10.1242/dev.073031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogozin I. B., Carmel L., Csuros M., Koonin E. V. (2012). Origin and evolution of spliceosomal introns. Biol. Direct 7:11. 10.1186/1745-6150-7-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy S. W., Penny D. (2006). Smoke without fire: Most reported cases of intron gain in nematodes instead reflect intron losses. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23 2259–2262. 10.1093/molbev/msl098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy S. W., Penny D. (2007). Patterns of intron loss and gain in plants: Intron loss-dominated evolution and genome-wide comparison of O.sativa and A.thaliana. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24 171–181. 10.1093/molbev/msl159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuma Y., Liu Q., Dubouzet J. G., Abe H., Shinozaki K., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. (2002). DNA-binding specificity of the ERF/AP2 domain of Arabidopsis DREBs, transcription factors involved in dehydration- and cold-inducible gene expression. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 290 998–1009. 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar T., Thankappan R., Mishra G. P., Nawade B. D. (2019). Advances in the development and use of DREB for improved abiotic stress tolerance in transgenic crop plants. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 25 1323–1334. 10.1007/s12298-019-00711-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savojardo C., Martelli P. L., Fariselli P., Profiti G., Casadio R. (2018). BUSCA: An integrative web server to predict subcellular localization of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 46 W459–W466. 10.1093/nar/gky320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X., Wang J. C., Zhang D. Y., Gaskin J. F., Pan B. R. (2010). Pollination ecology of the rare desert species Eremosparton songoricum (Fabaceae). Aust. J. Bot. 58 35–41. 10.1071/bt09172 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y., Liu H., Gao Y., Wang Y., Wu M., Xiang Y. (2019). Genome-wide identification of growth-regulating factors in moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis): In silico and experimental analyses. PeerJ 7:e7510. 10.7717/peerj.7510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu Y., Liu Y., Zhang J., Song L., Guo C. (2016). Genome-wide analysis of the AP2/ERF superfamily genes and their responses to abiotic stress in Medicago truncatula. Front. Plant Sci. 6:1247. 10.3389/fpls.2015.01247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X., Li Y., Hou X. (2013). Genome-wide analysis of the AP2/ERF transcription factor superfamily in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa ssp pekinensis). BMC Genomics 14:573. 10.1186/1471-2164-14-573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X., Wang J., Ma X., Li Y., Lei T., Wang L., et al. (2016). Origination, expansion, evolutionary trajectory, and expression bias of AP2/ERF superfamily in Brassica napus. Front. Plant Sci. 7:1186. 10.3389/fpls.2016.01186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian B., Gao S. H., Lercher M. J., Hu S. N., Chen W. H. (2019). Evolview v3: A webserver for visualization, annotation, and management of phylogenetic trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 47 W270–W275. 10.1093/nar/gkz357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z. M., Zhou M. L., Dan W., Tang Y. X., Lin M., Wu Y. M. (2016). Overexpression of the Lotus corniculatus Soloist gene LcAP2/ERF107 enhances tolerance to salt Stress. Protein Pept. Lett. 23 442–449. 10.2174/0929866523666160322152914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z. M., Zhou M. L., Xiao X. G., Tang Y. X., Wu Y. M. (2014). Genome-wide analysis of AP2/ERF family genes from Lotus corniculatus shows LcERF054 enhances salt tolerance. Funct. Integr. Genomics. 14 453–466. 10.1007/s10142-014-0372-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szklarczyk D., Gable A. L., Nastou K. C., Lyon D., Kirsch R., Pyysalo S., et al. (2021). The STRING database in 2021: Customizable protein–protein networks, and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 49 D605–D612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Stecher G., Kumar S. (2021). MEGA11: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38 3022–3027. 10.1093/molbev/msab120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. D., Higgins D. G., Gibson T. J. (1994). CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22 4673–4680. 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian F., Yang D.-C., Meng Y.-Q., Jin J., Gao G. (2019). PlantRegMap: Charting functional regulatory maps in plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 48 D1104–D1113. 10.1093/nar/gkz1020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valliyodan B., Nguyen H. T. (2006). Understanding regulatory networks and engineering for enhanced drought tolerance in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 9 189–195. 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z. S., Chen M., Li L. C., Ma Y. Z. (2011). Functions and application of the AP2/ERF transcription factor family in crop improvement. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 53 570–585. 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2011.01062.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng L., Yin Y., You C., Pan Q., Xu D., Jin T., et al. (2016). Evolution and protein interactions of AP2 proteins in Brassicaceae: Evidence linking development and environmental responses. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 58 549–563. 10.1111/jipb.12439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng L., Zhang N., Zhang Q., Endress P. K., Huang J., Ma H. (2017). Resolution of deep eudicot phylogeny and their temporal diversification using nuclear genes from transcriptomic and genomic datasets. New Phytol. 214 1338–1354. 10.1111/nph.14503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng L. P., Zhang Q., Sun R. R., Kong H. Z., Zhang N., Ma H. (2014). Resolution of deep angiosperm phylogeny using conserved nuclear genes and estimates of early divergence times. Nat. Commun. 5:4956. 10.1038/ncomms5956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G., Chen M., Chen X., Xu Z., Guan S., Li L.-C., et al. (2008). Phylogeny, gene structures, and expression patterns of the ERF gene family in soybean (Glycine max L.). J. Exp. Bot. 59 4095–4107. 10.1093/jxb/ern248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Liao J., Ling Q., Xi Y., Qian Y. (2022). Genome-wide identification and expression profiling analysis of maize AP2/ERF superfamily genes reveal essential roles in abiotic stress tolerance. BMC Genom. 23 125–125. 10.1186/s12864-022-08345-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Zhu C., Lyu Y., Chen Y., Zhang Z., Lai Z., et al. (2020). Genome-wide identification, molecular evolution, and expression analysis provide new insights into the APETALA2/ethylene responsive factor (AP2/ERF) superfamily in Dimocarpus longan Lour. BMC Genomics 21:62. 10.1186/s12864-020-6469-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S., Xu Z., Zheng W., Zhao W., Wang Y., Yu T., et al. (2017). Genome-wide analysis of the RAV family in soybean and functional identification of GmRAV-03 involvement in salt and drought stresses and exogenous ABA treatment. Front. Plant Sci. 8:905. 10.3389/fpls.2017.00905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Zhang R., Jiang K.-W., Qi J., Hu Y., Guo J., et al. (2021). Nuclear phylotranscriptomics and phylogenomics support numerous polyploidization events and hypotheses for the evolution of rhizobial nitrogen-fixing symbiosis in Fabaceae. Mol. Plant. 14 748–773. 10.1016/j.molp.2021.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang J., Cai B., Peng R.-H., Zhu B., Jin X.-F., Xue Y., et al. (2008). Genome-wide analysis of the AP2/ERF gene family in Populus trichocarpa. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 371 468–474. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary material.