Abstract

We report the one-step synthesis of diversely substituted functional 1,2-dithiolanes by reacting readily accessible 1,3-bis-tert-butyl thioethers with bromine. The reaction proceeds to completion within minutes under mild conditions, presumably via a sulfonium-mediated ring-closure. Using X-ray crystallography and UV-vis spectroscopy, we demonstrate how substituent size and ring substitution pattern can affect the geometry and photophysical properties of 1,2-dithiolanes.

Graphical Abstract

1,2-Dithiolanes are five-membered heterocyclic molecules comprising a disulfide bond. The intricate reactivity of this class of disulfides, arising from the geometric constraints imposed upon the sulfur-sulfur (S–S) bond, has been exploited for cell-uptake applications,1–6 reversible protein-polymer conjugation,7 biosensors,8 dynamic networks,9–14 and functional polymer synthesis.15,16

Distinct from linear disulfides, which usually exhibit CSSC dihedral angles around 90°, the five-membered cyclic geometry of 1,2-dithiolanes forces the disulfide scaffold into conformations with CSSC dihedral angles lower than 35° (Figures 1A and S1A).17,18 At such low dihedral angles, the neighboring fully occupied non-bonding sulfur orbitals overlap,19,20 causing a destabilizing four-electron interaction, also known as closed-shell repulsion (Figure S1A).21 This stereoelectronic effect weakens the S–S bond, rendering 1,2-dithiolanes prone to rapid thiol-disulfide exchange22,23 and ringopening polymerization.7,16,24 Such polydisulfides generated from 1,2-dithiolanes are typically dynamic and can be reversibly depolymerized,12,25,26 a phenomenon that has been exploited for the direct polydisulfide-mediated cytosolic delivery of various cargo,27 such as proteins,5 quantum dots,28 or silica particles.29

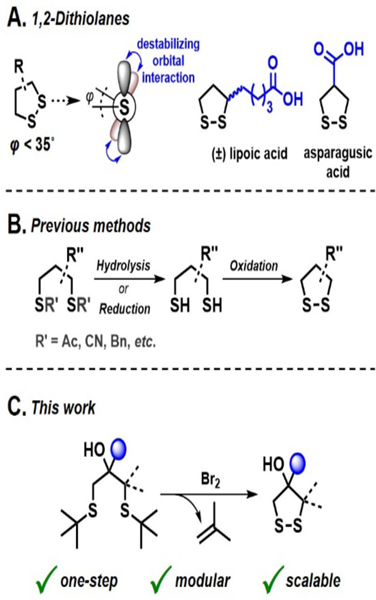

Fig. 1.

Electronic properties and synthesis of 1,2-dithiolanes. (A) The low CSSC dihedral angle (φ) imparts 1,2-dithiolanes, such as lipoic or asparagusic acid, with unique reactivity. (B) Previous syntheses of 1,2-dithiolanes involved a two-step reaction sequence. (C) Our strategy provides hydroxy-functional 1,2-dithiolanes in a single step from readily available 1,3-bis-tert-butyl thioether substrates.

In addition to the CSSC dihedral angle, a determining factor for the reactivity of 1,2-dithiolanes is the ring substitution pattern.12,30,31 For example, Matile’s group reported profound differences in the polymerization behavior24 and the cell uptake efficiency2 of lipoic acid and asparagusic acid (Figure 1A). Whitesides and coworkers showed that higher-substituted 1,2-dithiolanes are more resistant towards reduction and ringopening (Figure S1B).22 Considering these results, we believe there is great potential in controlling 1,2-dithiolane reactivity via tailored substituent selection. However, most application-focused reports revolve around commercially available lipoic acid (Figure 1A) and its amide or ester derivatives. This lack of substrate variety is arguably due to the limited synthetic accessibility of substituted 1,2-dithiolane derivatives with functional handles for downstream modification. 1,2-Dithiolanes are commonly synthesized in a two-step sequence, which includes generation of the 1,3-dithiol via hydrolysis or reduction of suitable precursors, followed by oxidation to the corresponding 1,2-dithiolane (Figure 1B). However, formation of the 1,3-dithiol often requires harsh reaction conditions that limit functional group tolerance and often lead to undesired polydisulfide formation. To overcome these synthetic limitations and expand the substrate toolbox for applications of 1,2-dithiolanes, we developed a modular one-step synthesis of diversely substituted 1,2-dithiolanes from readily accessible 1,3-bis-tert-butyl thioethers (Figure 1C). Furthermore, the 1,3-bis-tert-butyl thioethers were designed to feature a hydroxy group that can be used as a handle for downstream functionalizations of the 1,2-dithiolane product.

tert-Butyl protection of thiols is typically known for robustness and stability.32,33 However, Mayor34 and later Feringa35 leveraged the tert-butyl group for the direct transformation of S-tert-butyl thioethers into thioacetates using acetyl chloride and a catalytic amount of Br2 or TiCl4, respectively. Specifically intriguing to us was Mayor’s observation of disulfide side products during the reaction.34 Based on these reports, we tested if S-tert-butyl cleavage in combination with intramolecular disulfide formation promoted by electrophilic halogen reagents could provide access to 1,2-dithiolanes from 1,3-bis-tert-butyl thioethers in a single step. Optimization of the reaction conditions with thioether 1a as a substrate showed that Br2, in combination with hydrated silica gel, was most effective for the targeted transformation, yielding 4-hydroxy-4-phenyl-1,2-dithiolane PhDL in 77% isolated yield (Table 1). The addition of silica gel to the reaction mixture improved the yield (entries 1 and 2), presumably by scavenging reactive byproducts,36 which could be visually confirmed by the discoloration of the silica gel over the course of the reaction. While the slow addition of 1.3 equivalents of Br2 typically led to full conversion of 1a, lower reaction temperatures required increased amounts of Br2 for the reaction to complete (entry 3). Other electrophilic halogen reagents, such as N-bromosuccinimide (NBS) or 1,2-dibromotetrachloroethane (C2Cl4Br2), were less effective or showed no reaction (entries 4–6).

Table 1.

Optimization of reaction conditionsa

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Entry | Deviation from standard conditions | Yieldb (%) |

| 1 | None | 77 |

| 2 | No silica gel | 52 |

| 3c | 0 °C | 24 |

| 4d | NBS instead of Br2 | 28 |

| 5 | C2Cl4Br2 instead of Br2 | n. r. |

| 6 | I2 instead of Br2 | n. r. |

All reactions were run to full conversion of 1a unless no reaction (n. r.) was observed. Standard conditions: 1a (1.0 mmol), silica gel ([g silica gel] / [mmol 1a] = 2), DCM (20 mL), room temperature (r. t.).

Isolated yield after column chromatography.

2.2 equiv Br2.

3 equiv NBS.

Analysis of the crude reaction mixture by 1H NMR spectroscopy and GC-MS showed the formation of 1,2-dibromo-2-methylpropane and tert-butyl bromide as the major byproducts (Figures S2–S5). Based on these results, we propose that ring closure proceeds via the initial formation of sulfonium bromide A,37 followed by elimination of isobutylene (Figure 2). The activated sulfenyl bromide B could then undergo intramolecular cyclization to compound C, which yields the target 1,2-dithiolane after another elimination of isobutylene. Isobutylene (Tb = −6.9 °C) either evaporates from the reaction mixture or reacts with Br2 and HBr to form 1,2-dibromo-2-methylpropane and tert-butyl bromide, respectively (Figure 2). The higher solubility of isobutylene in the mixture at lower temperatures would also explain the increased consumption of Br2 at 0 °C (Table 1, entry 3).

Fig. 2.

Proposed reaction mechanism for the deprotection-disulfide formation sequence affording 4-hydroxy-4-phenyl-1,2-dithiolane (PhDL). After elimination, isobutylene either evaporates or is converted into brominated byproducts.

Having established this synthetic strategy, we aimed to generate multiple 1,3-bis-tert-butyl thioether compounds (Figure S6) for the subsequent transformation into 1,2-dithiolanes (Figure 1C). Specifically, we synthesized 1,3-bis-tert-butyl thioethers 1a–1l from various 1,3-dichloropropan-2-ol derivatives, α,α′-halogenated ketones, and 2-(chloromethyl)oxiranes with tert-butylthiol and K2CO3 as a base in DMF at room temperature (Figure S6). This broad range of suitable starting materials suggests that a variety of 1,3-bis-tert-butyl thioether substrates can be readily generated by this protocol. Notably, the reaction could be conducted on multigram scales (1a and 1f) and all products were obtained in good yield and purity, often without the need of chromatographic purification.

Following the 1,3-bis-tert-butyl thioether preparation, we used the optimized Br2-induced ring-closure conditions (Table 1) to convert 1,3-bis-tert-butyl thioethers 1a–1f and 1l into 4-hydroxy-1,2-dithiolanes with moderate to good yields (Figure 3). This approach provided access to seven new 1,2-dithiolane derivatives with unprecedented ring substitution and functionality (Figure 3). Geminal to the hydroxy group, the substituents were varied from hydrogen (HDL) to propyl (nPrDL), isopropyl (iPrDL), and dodecyl (C12DL); phenyl (PhDL), thiophenyl (TphDL), and bromothiophenyl (BrTphDL) groups could be installed as aromatic analogues. Additionally, we created an intriguing alternative 1,2-dithiolane scaffold with gem-dimethyl substitution vicinal to the disulfide bond (DiMeDL). Importantly, this reaction proved efficient on multigram scales (iPrDL and PhDL), which will be beneficial in 1,2-dithiolane applications.

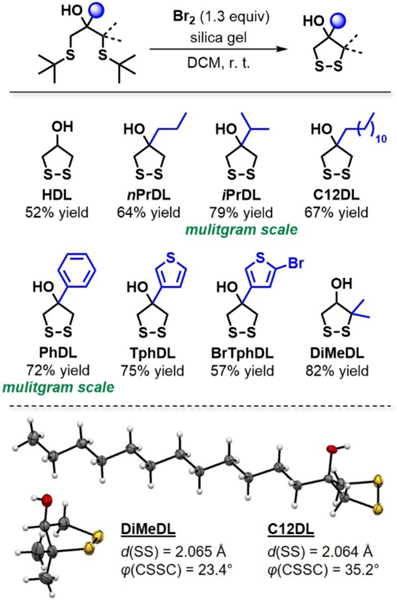

Fig. 3.

Preparation of hydroxy-functional 1,2-dithiolanes with isolated yields. The lower yield of HDL is likely due to auto-polymerization during purification. The X-ray crystal structures of DiMeDL and C12DL show a shortened S–S bond length (d) and a compressed CSSC dihedral angle (φ).

With the compounds in hand, we sought to evaluate the effect of substituent size and substitution pattern on 1,2-dithiolane ring conformation, since the geometry and dihedral angle of the disulfide moiety profoundly affects the properties of 1,2-dithiolanes (Figure S1A). The crystal structures of C12DL and DiMeDL (Figure 3) revealed similarly elongated S–S bond lengths around 2.06 Å (linear disulfide bond lengths are typically around 2.03 Å)17 but differing CSSC dihedral angles of 35.2° and 23.4°, respectively. Interestingly, this CSSC dihedral angle reduction coincided with a sharp decrease of the CCSS dihedral angle from 21° to 1° (Table S1). Comparison with all available crystal structures of unbridged and monocyclic 1,2-dithiolanes showed a similar, almost linear relationship between the CSSC and the CCSS dihedral angles (Tables S1–S2, Figure S7). We believe that such eclipsed CCSS conformations in 1,2-dithiolanes with low CSSC dihedral angles could potentially contribute to the reactivity associated with such compounds, warranting future investigations.

Next, we turned to UV-vis spectroscopy to analyze the maximum absorbance wavelength (λmax) of the first electronic transition (S0 → S1), which provides information about the S–S bond geometry in 1,2-dithiolanes. Specifically, the energy of S0 → S1 in disulfides is dependent on the overlap of the fully occupied non-bonding sulfur orbitals, which in turn is determined by the CSSC dihedral angle (Figure S1A).19,20 For example, a stronger orbital overlap at lower CSSC dihedral angles raises the HOMO energy while the LUMO remains largely unaffected,20 thus reducing the photon energy required for the excitation of S0 → S1.

For the 1,2-dithiolane products tested in this report, we recorded a slight increase of λmax upon geminal substitution on C4 (Figures 4, S8, and Table S3). HDL exhibited a λmax of 327 nm, whereas derivatives with alkyl and aromatic substituents on C4 showed λmax values around 335 and 339 nm, respectively. The absorbance bands of derivatives with aromatic substituents were generally broader than those of derivatives with alkyl substituents, suggesting differences in the anti-bonding character of S1.38 Substitution on C3 in DiMeDL resulted in a large λmax red-shift to 354 nm, which corroborates with the lower CSSC dihedral angle revealed in the crystal structure. These results suggest that ring substitution affects the geometry and the photophysical properties of 1,2-dithiolanes. Furthermore, based on the linear increase of λmax with C4 substituent A-values (Figure S9), we propose that the substituent effects in this position are mostly of steric nature.

Fig. 4.

Substituent effects on the photophysical properties of 1,2-dithiolanes. (A) Overlay of representative UV-vis absorbance spectra taken at 10 mM in DMSO. (B) Bar diagram showing the variation of the maximum absorbance wavelength (λmax) with respect to 4-hydroxy-1,2-dithiolane substituent.

Typically, low CSSC dihedral angles in 1,2-dithiolane compounds are associated with ring strain and S–S bond instability. For example, auto-polymerization has been commonly observed for 1,2-dithiolanes,12,18,25,39,40 an issue we also encountered during purification of the compounds. We noted dramatic stability differences between HDL and higher substituted iPrDL, and C12DL. For example, HDL could be used only in solution due to rapid polymerization upon concentration, whereas iPrDL and C12DL were bench-stable over weeks. While the crystalline nature of C12DL could have a stabilizing effect, HDL and iPrDL are liquids and still showed substantial differences in stability.

To further investigate this observation, we estimated the ring strain for HDL and iPrDL via quantum chemical calculations of the enthalpy of reaction (ΔrxnH) for the isodesmic reaction between 1,4-butanedithiol (BuSH) and HDL or iPrDL (Table 2). The value of ΔrxnH reflects the additional ring strain of the 1,2-dithiolane compound with respect to the relatively unstrained 1,2-dithiane (BuSS). The calculations revealed a ΔrxnH of –27.9 kJ/mol for HDL, which is slightly higher than the ring strain for 1,2-dithiolane determined by Sunner41 via iodine oxidation. Upon geminal substitution on C3 with an isopropyl group, ΔrxnH was reduced to –2.9 kJ/mol, corroborating with the higher stability of iPrDL observed experimentally, emphasizing the stabilizing effect from substitution in cyclic structures.12, 22, 42, 43

Table 2.

Ring strain calculations via the isodesmic reaction of 1,4-butanedithiol (BuSH) and 1,2-dithiane (BuSS) with a 1,2-dithiolane derivative in the ring-closed (DL) and 1,3-dithiol (C3SH) form.

Calculated via ΔrxnH = [ΔfH (BuSS) + ΔfH (C3SH)] − [ΔfH (BuSH) + ΔfH (DL)] All enthalpies of formation (ΔfH) were calculated for the gas phase at 298 K using a B3LYP/6-311G** basis set.

Determined from UV-vis spectroscopy (Table S4). Higher λmax values indicate lower CSSC dihedral angles.

Finally, to test if the hydroxy group incorporated in the 1,2-dithiolane structure was suitable for downstream modifications, we reacted PhDL with isobutyryl chloride, affording 1,2-ditholane ester 2 in good yield (Figure 5). Using the same strategy, we synthesized 1,2-dithiolane acrylate 3 from iPrDL and acryloyl chloride. The subsequent base-catalyzed thia-Michael addition between benzyl mercaptan and 3 provided Michael adduct 4 in high yield. We believe that such transformations could be particularly useful in applications that require covalent conjugation of 1,2-dithiolanes to substrates such as proteins or polymers.

Fig. 5.

Downstream functionalization of 1,2-dithiolanes, exploiting the hydroxy functionality. Triethylamine (TEA) was used as a base with 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) as a catalyst in the esterification of PhDL. 1,8-Diazabicylcoundec-7-ene (DBU) was employed in the base-catalyzed thia-Michael addition of 1,2-dithiolane acrylate 3 with benzyl mercaptan.

In conclusion, we disclosed a scalable and straightforward synthetic protocol for diversely substituted new 1,2-dithiolane compounds featuring a hydroxy functionality as a valuable handle for downstream conjugation. X-ray crystallography, UV-vis spectroscopy, and quantum chemical calculations revealed profound substitution effects on the stereoelectronic properties and the stability of the 1,2-dithiolane derivatives, suggesting that 1,2-dithiolane reactivity can be tuned by careful substituent design. We believe this report represents an attractive avenue for the future design of 1,2-dithiolanes in advanced applications, such as cargo delivery and stimuli-responsive polymer materials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the DoD (W911NF-17-1-0326) and the NSF (DMR-1904631, CHE-1808234). The University of Florida Department of Chemistry Mass Spectrometry Center acknowledges NIH (S10 OD021758-01A1), and K.A.A. wishes to acknowledge NSF for funding the X-ray diffractometer through CHE-1828064. The authors thank Prof. Yuan-Chung Cheng (National Taiwan University) for providing the calculation resource and Dr. Ion Ghiviriga (University of Florida) for assistance with NOE experiments.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Procedures, calculations, and characterization data. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts to declare.

Notes and references

- 1.Gasparini G, Bang EK, Molinard G, Tulumello DV, Ward S, Kelley SO, Roux A, Sakai N. and Matile S, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2014, 136, 6069–6074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gasparini G, Sargsyan G, Bang EK, Sakai N. and Matile S, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2015, 54, 7328–7331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abegg D, Gasparini G, Hoch DG, Shuster A, Bartolami E, Matile S. and Adibekian A, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2017, 139, 231–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fu J, Yu C, Li L. and Yao SQ, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2015, 137, 12153–12160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qian L, Fu J, Yuan P, Du S, Huang W, Li L. and Yao SQ, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2018, 57, 1532–1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chuard N, Gasparini G, Moreau D, Lorcher S, Palivan C, Meier W, Sakai N. and Matile S, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2017, 56, 2947–2950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu J, Wang H, Tian Z, Hou Y. and Lu H, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2020, 142, 1217–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang L, Duan D, Liu Y, Ge C, Cui X, Sun J. and Fang J, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2014, 136, 226–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Q, Shi C-Y, Qu D-H, Long Y-T, Feringa BL and Tian H, Sci. Adv, 2018, 4, No. eaat8192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Q, Deng Y-X, Luo H-X, Shi C-Y, Geise GM, Feringa BL, Tian H. and Qu D-H, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2019, 141, 12804–12814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barcan GA, Zhang X. and Waymouth RM, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2015, 137, 5650–5653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang X. and Waymouth RM, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2017, 139, 3822–3833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deng Y, Zhang Q, Feringa BL, Tian H. and Qu D-H, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2020, 59, 5278–5283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scheutz GM, Rowell JL, Ellison ST, Garrison JB, Angelini TE and Sumerlin BS, Macromolecules, 2020, 53, 4038–4046. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang H. and Tsarevsky NV, Polym. Chem, 2015, 6, 6936–6945. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Y, Jia Y, Wu Q. and Moore JS, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2019, 141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steudel R, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 1975, 14, 655–664. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teuber L, Sulfur Rep., 1990, 9, 257–333. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bergson G, Ark. Kemi, 1958, 12, 233–237. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boyd DB, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1972, 94, 8799–8804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anslyn EV and Dougherty DA, Modern Physical Organic Chemistry, University Science Books, Sausalito, California, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Houk J. and Whitesides GM, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1987, 109, 6825–6835. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh RW, Whitesides GM, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1990, 112, 6304–6309. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bang EK, Gasparini G, Molinard G, Roux A, Sakai N. and Matile S, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2013, 135, 2088–2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelander B, Acta Chem. Scand, 1971, 25, 1510–1511. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Danehy JP and Elia VJ, J. Org. Chem, 1972, 37, 369–373. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Du S, Liew SS, Li L. and Yao SQ, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2018, 140, 15986–15996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Derivery E, Bartolami E, Matile S. and Gonzalez-Gaitan M, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2017, 139, 10172–10175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu C, Qian L, Ge J, Fu J, Yuan P, Yao SC and Yao SQ, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2016, 55, 9272–9276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carmine A, Domoto Y, Sakai N. and Matile S, Chem. Eur. J, 2013, 19, 11558–11563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burns JA and Whitesides GM, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1990, 112, 6296–6303. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wuts PGM, Greene’s Protective Groups in Organic Synthesis, John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nishimura O, Kitada C. and Fujino M, Chem. Pharm. Bull, 1978, 26, 1576–1585. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Błaszczyk A, Elbing M. and Mayor M, Org. Biomol. Chem, 2004, 2, 2722–2724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pijper TC, Robertus J, Browne WR and Feringa BL, Org. Biomol. Chem, 2015, 13, 265–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ali MH and McDermott M, Tetrahedron Lett., 2002, 43, 6271–6273. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anklam E, Synthesis, 1987, 1987, 841–843. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Antonov L. and Nedeltcheva D, Chem. Soc. Rev, 2000, 29, 217–227. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Claeson G, Acta Chem. Scand, 1955, 9, 178–180. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Field L. and Barbee RB, J. Org. Chem, 1969, 34, 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sunner S, Nature, 1955, 176, 217. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jung ME and Piizzi G, Chem. Rev, 2005, 105, 1735–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu H, Nelson AZ, Ren Y, Yang K, Ewoldt RH and Moore JS, ACS Macro Lett., 2018, 7, 933–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.