Abstract

Introduction:

Effective and appropriate provision of mental healthcare has long been a struggle globally, resulting in significant disparity between prevalence of mental illness and access to care. One attempt to address such disparity was the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), 2010, mandate in the United States to integrate physical and mental healthcare in Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs). The notion of integration is attractive, as it has demonstrated the potential to improve both access to mental healthcare and healthcare outcomes. However, while the PPACA mandate set this requirement for FQHCs, no clear process as to how these centers should achieve successful integration was identified.

Methods:

This research employed case study methods to examine the implementation of this policy in two FQHCs in New England. Data were obtained from in-depth interviews with leadership, management, and frontline staff at two case study sites.

Results:

Study findings include multiple definitions of and approaches for integrating physical and mental healthcare, mental healthcare being subsumed into, rather than integrated with, the medical model and multiple facilitators of and barriers to integration.

Conclusion:

This study asked questions about what integration means, how it occurs, and what factors facilitate or pose barriers to integration. Integration is facilitated by co-location of providers within the same department, a warm hand-off, collaborative collegial relationships, strong leadership support, and a shared electronic health record. However, interdisciplinary conflict, power differentials, job insecurity, communication challenges, and the subsumption of mental health into the medical model pose barriers to successful integration.

Keywords: Integration of care, access to care, policy, medicine access, mental healthcare

Introduction

In the United States, approximately 46.4% of all adults will experience mental illness during their lifetime, but a well-documented disparity persists between the numbers of people who are living with a mental illness and those who access services and treatment.1–3 In 2019, 20.6% of US adults were diagnosed with a mental illness, less than half of whom received any mental health service. In the same year, incidence of serious mental illness, that is, those that significantly impair an individual’s ability to carry out regular life activities, was 5.2% of US adults, of whom 65% received mental health services. 4

A significant piece of legislation that sought to address problems of access to services for people with mental illness was the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), 2010. The Act’s stated intent is to “improve access to and the delivery of healthcare services for all individuals, particularly low income, underserved, uninsured, minority, health disparity, and rural populations.” 5 One goal is to promote the integration of physical and mental healthcare in community-based centers.

This article presents findings that provide a roadmap for Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) to integrate physical and mental healthcare, discussing both facilitators and barriers to integration. To understand the process of integration, a background on the development of FQHCs and of health center organizational behavior is provided.

The development of community-based care

The development of US mental health policy demonstrates a shift over time from the asylums and self-reliance of the 18th-century mental health ethos to the large inpatient psychiatric facilities of the 19th century to care in the community, first proposed in the mid-20th century.6,7 Numerous policies, including the National Mental Health Act, 1946, the Community Mental Health Centers Act, 1963, and the Mental Health Parity and Addictions Equity Act, 2008, were developed to attempt to address the aforementioned gap between prevalence of mental illness and access to services.

Individuals are more likely to follow up on referrals to mental healthcare if such care is provided in the same location as their physical healthcare and if their providers work in a multidisciplinary team.8,9 Furthermore, by providing physical and mental healthcare in one setting, the idea of accessing mental health services is normalized. 10 Community Health Centers (CHCs) were established in the 1960s to provide healthcare to low-income individuals with limited or no health insurance.11,12 Following the establishment of these centers came FQHCs that provide comprehensive healthcare, including, but not limited to, physical healthcare, mental healthcare, and dental care to low-income individuals in their community. Nationally, the number of FQHCs increased from 545 in 1990 to 1385 in 2019. 13

The PPACA (2010) mandated that FQHCs integrate physical and mental healthcare and provided US$11 billion in new FQHC funds to support this integration. 14 The objective then of the PPACA mandate for FQHCs to integrate physical and mental healthcare was to provide comprehensive care, improve outcomes, and reduce disparities in treatment.5,15–18 Integrated behavioral health can be delivered in a brief, economical format, and research demonstrates positive clinical outcomes, as well as high levels of patient and health provider satisfaction.19–22

Organizational behavior

An organization’s culture, mission, and relationships between different levels of agency workers impact outcomes. Organizational culture and influence are shaped by the agency’s values and beliefs, and organizational culture informs its mission and purpose.23,24 Any one agency can have competing cultures, although one culture may be more prominent than others. This can give rise to problems when tasks that fall outside the purview of the dominant culture do not get the same attention or resource allocation. 25 Thus, decision making about which services receive resources is indicative of the agency’s perception of the value of mental healthcare relative to other priorities, and a commitment to truly integrate care. 26

The dynamic between agency leaders, management, and practitioners and the effect on outcomes

Relationships and communication between workers at different levels within an agency have importance in how care is provided and integration policy is implemented. The top-down approach focuses on the role of leadership in policymaking and implementation.27–29 Leadership (the top) establishes agency goals, policies, and practices, and frontline workers (the bottom) carry out their directives and it is how leadership perceives mental illness that shapes service delivery. However, the bottom-up approach suggests that it is frontline workers or street-level bureaucrats who have influence and discretion in implementing and creating policy; thus, their perceptions of mental illness can impact how policies are put into practice. 30 Thus, the top-down approach focuses on goal achievement, whereas the bottom-up approach focuses on problem solving.31–33

The purpose of the research is to understand the facilitators and barriers to integrating physical and mental healthcare in FQHCs. The research questions how organizational policies serve the needs of different actors; therefore, it is important to consider integration from different perspectives within the FQHC.

Methodology

Study design

This article analyzes findings from a 6-month qualitative study to understand how physical and mental health integration occurs in FQHCs. The study was conducted by the first author, comparing and contrasting the state of integration in two FQHCs, via two methodologies. 34 First, a case study methodology was utilized to understand the co-location, coordination, and integration of each center from its respective employees. Second, a critical epistemology was utilized, to capture impressions of practical deployment of integration by the degree of equality, empowerment, and voice of the different levels of actors at each site. The rationale for using this approach is that the case study methodology permitted deep analysis of FQHCs’ policies and practices and the critical approach seeks to uncover inequality and disparity in society. The study involved the collection and qualitative analysis of data obtained from in-depth interviews with agency staff at two FQHCs. 35

Sampling strategy and ethical issues

The research took place at FQHCs situated in a large urban center in the New England region (USA). An initial set of 15 potential sites was identified from an analysis of characteristics of local FQHCs; final selection was informed by consideration of a number of criteria (see Table 1). Taking these criteria into account, two FQHCs, Site A and Site B, met all inclusion criteria. Participants were recruited by purposive and by snowball sampling. Prior to beginning the research, a full Institutional Review Board (IRB) application was approved by the University of Massachusetts in December 2013 (Protocol #: 2013227); the study was completed in 2015.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participating sites.

| Criteria/characteristics | Site A | Site B |

|---|---|---|

| Large urban location | Yes | Yes |

| Independent (not part of larger organization) | Yes | Yes |

| Provision of onsite specialized mental health services | Yes | Yes |

| Integrating physical and mental healthcare | Yes | Yes |

| Publicly accessible reports | Yes | Yes |

| Board at least 51% patient representatives | No | Yes |

| Leadership supportive of this project | Yes | Yes |

| Total number of patients enrolled | 14,687 | 11,772 |

| Patients utilizing MHS | 726 | 494 |

| Clients using MHS as % of total client population | 4.94% | 4.2% |

| % Increase of patients accessing MHS 2010–2012 | 70.4% | 40.7% |

| MHS expenses as % of operating revenue | 31.98% | 8% |

| % Patients at or below 100% of poverty line | 64.1% | 63.4% |

| % Patients at or below 200% of poverty line | 91.6% | 94.4% |

| Racial and/or ethnic minority | 95.7% | 81.7% |

MHS: Mental Health Services.

Units of study

In terms of this case study, the two study sites are exceptional in that they have been providing some type of integrated physical and mental healthcare to their patients for some considerable time. This history makes these two FQHCs important sites for study precisely because both began the process of integrating physical and mental healthcare well before the PPACA mandate. Early experience of integrating care permitted interviewees from the two case study sites to reflect on the process to date. This reflective knowledge was important in identifying influences that both facilitated and created barriers to integration, insights that might have been unavailable in sites with less experience of integrating care.

The sites identified as fully integrated, as opposed to co-located traditional outpatient centers or utilizing the care management model. 36 However, the two case study sites offered slightly different approaches to the full integration model. Site A was integrating care in two stages. It had integrated pediatric care by 2011 and was in the process of integrating adult care at the time the case study was being conducted; leadership stated that the decision to integrate was solely a financial one (i.e. outcome-oriented). However, Site B has offered integrated pediatric and adult care in a family practice setting since its inception in the 1970s, as leadership believed that this was the best way to meet patient needs and to improve outcomes for the community (i.e. mission and values oriented).

Data collection methods

A total of 21 in-depth, in-person open-ended interviews were conducted with representatives from leadership, management, and frontline practitioners across the two sites. All participants were given an information sheet about the study, were able to ask questions, and provided written informed consent to be interviewed and recorded. Leadership representatives were from the Executive Officer/Medical Director/Chief Behavioral Health Officer level, while managers were Program Directors, or similar. Frontline mental health workers were those providing direct care and/or services to patients and include social workers, mental health counselors, and outreach workers. Interviewing staff members from different levels in the hierarchy at the two case study agencies provided an understanding of the phenomena studied from varied perspectives. 37

Data collection instruments and technologies

Interview protocols were designed to uncover processes and attitudes about PPACA integration policy development and implementation, service provision, client groups, and mental illness in general. The interview protocols (see Appendix 1) included questions about allocation of resources, integration of physical and mental healthcare, attitudes about mental illness, and willingness to implement mental health services. Questions were also asked about possible challenges or barriers to integration and provision of treatment. 38 Interviews were recorded on a portable, handheld digital voice recorder.

Data processing

Audio files of the recoded interviews were downloaded and stored on a password-protected computer. These files were shared with a professional transcription service via encrypted email. The transcriptionist transcribed the interviews verbatim, and ensuing data from all sources were anonymized, coded, and analyzed using HyperResearch software.

Data analysis

Data were first sorted using analysis matrices (created by the Principal Investigator) and informed by the conceptual framework that had been developed to understand the process of implementation of federal policy to integrate physical and mental healthcare.30,39 The conceptual framework was informed by literature on theories of organizational relationships,40–42 street-level bureaucracy,30,43,44 stigma,45,46 and social construction.47–49

From the matrices, codes and a codebook were developed and analyzed to search for confirming and disconfirming evidence of how policy implementation takes place, when compared to assumptions made in the conceptual framework. The main analytic technique employed was inductive pattern matching, whereby patterns found in the data analysis were compared with those predicted in the conceptual framework and literature review. 35

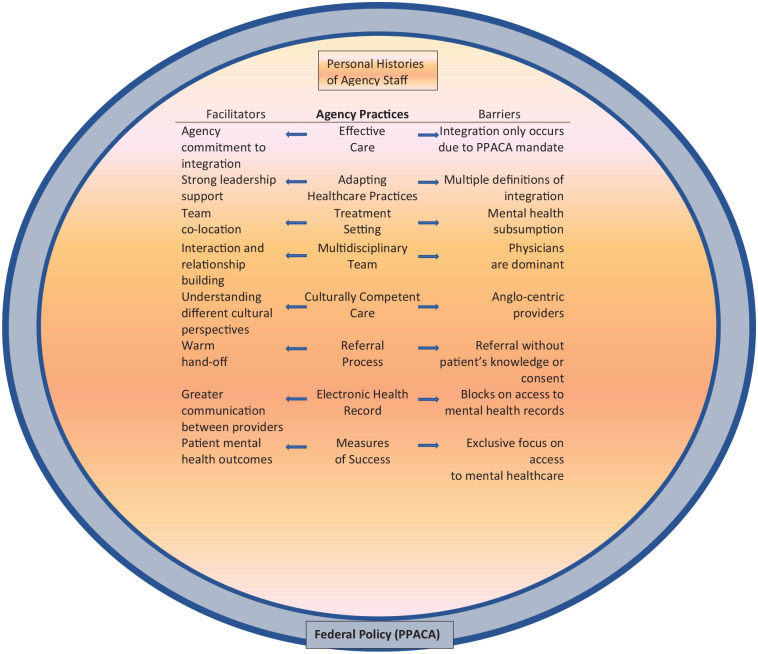

Techniques to enhance trustworthiness

The numerous data sources used in this study allowed for triangulation, thus improving the internal validity of this research. Analysis of the data was carried out until theoretical saturation was reached, that is, no new information was arising from analysis. 35 The external validity of this research is evidenced not by its statistical generalizability but in its analytic transferability; that is, theories of facilitators and barrier to healthcare integration help to identify other cases in which the results may be transferable. These results may be applicable to other health centers, FQHC, or otherwise, in the United States or globally, as such institutions work to successfully integrate care. The explanatory framework of facilitators and barriers to integration promotes replicability and transferability by providing future researchers with a tool to engage in additional study of policy implementation in other contexts (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Influences on the integration of physical and mental healthcare in FQHC practices.

Results

Synthesis and interpretation

Since the 2010 PPACA mandate that FQHCs integrate physical and mental healthcare, such centers have been working to comply with this directive. Extant research posits that integration increases patient access to mental healthcare and improves outcomes. 50 However, given that the legislation does not provide a clear path to such integration, many FQHCs have struggled with successful implementation. This case study of two FQHCs with a longer history of and experience with integrating care offers important insights into the facilitators of and barriers to successful integration (see Figure 1). Given that many FQHCs are in the early stages of integration, there are valuable lessons to be learned from study of other centers where integration policy has already been implemented.

Facilitators of integration

Co-location of physical and mental healthcare providers

Respondents posited that the most critical factor relating to successful implementation of integration policy was the co-location of physical and mental healthcare providers. Interviewees at both case study sites defined co-location as the provision of physical and mental healthcare services in the same department, in the same physical space. Respondents strongly argued that co-locating services within one department was the optimal way to ensure that integration works and that patients have improved access to mental healthcare. When discussing referrals from physical healthcare to mental healthcare within the organization, one member of leadership at Site A noted:

We have them . . . within our clinic. I think even having them across the hall reduces the level of communication, the intensity of communication, the quality of communication and all of that boils down to ending up with fewer referrals.

This respondent was one of many who noted the importance of proximity; the process of integrating care was expedited when both sets of providers were housed together as a multidisciplinary team, rather than as independent providers.

Medical providers were more likely to make referrals to mental health providers when they shared the same space. Furthermore, by being in such close proximity, physicians report being more likely to physically introduce patients to the mental health providers on staff. This warm hand-off, in turn, increased patient uptake of referrals and follow-through with treatment.

Interestingly, both sites experienced a temporary interruption of co-location of integrated behavioral health services, due to limitations in space that was being remedied by new construction. Site A moved behavioral health staff out of the medical suite while awaiting the completion of a construction remodeling project; Site B temporarily moved the behavioral health staff to a separate floor from the medical providers while construction on a new building was completed. While it may seem insignificant to patient care that the providers at Site B were a floor apart, providers at Site A noted that, since the mental healthcare providers had been moved approximately 40 feet across the hall, referral to mental healthcare by primary care providers had dropped by around 50%. One respondent stated that being separated was not beneficial to integrating care:

I do think it feels different. Yeah. I don’t like it . . . in the new building that’s being built, on purpose I made it very clear that I thought it would be beneficial . . . so we will be (co-located again). (Manager, Site B)

The warm hand-off

Numerous respondents cited the above-mentioned warm hand-off as another important prerequisite for successful integration. While co-location in itself led to more referrals being made by primary care to mental healthcare providers, it was this warm hand-off that actually increased the number of patients following up on the referrals and accessing mental health services. “More clients follow through with referral since integration . . . the warm handoff increases the probability that clients will engage with treatment” (Frontline Practitioner, Site A). Interviewees stated that this increased patient engagement was due to patients being able to meet the mental health provider who would be involved in their care, in person, before making an appointment. The fact that their primary care doctor, with whom they had a relationship, made the introduction helped patients feel more comfortable in accessing mental health services.

Collaborative relationships between providers

A third facilitating factor noted by respondents was the presence of a collaborative, collegial relationship between providers. 51 Having physical and mental health providers who not only respect each other but also understand their respective roles and who worked together to provide holistic care to patients promoted successful integration of care. Many respondents noted that it was important for physical and mental health providers to speak the same language and to develop treatment plans that focused on providing the most appropriate and effective care for patients. Co-location facilitated these relationships, as individuals who might not otherwise meet, but for large agency-wide meetings, now shared a multidisciplinary workspace. This shared space not only included neighboring offices but also shared lunchrooms and other facilities, which allowed for more social interaction and growth of personal and professional relationships. Case conferences were another opportunity for multidisciplinary discussions about and sharing perspectives on individual patients, thus further facilitating the relationship building and cross-disciplinary learning process.

Leadership in the medical team at Site A stated that, for primary care providers, one of the most important pieces that facilitated the integration process was having a mental health clinician already in place, embedded in the medical team. At Site B, where integration occurred at inception, being co-located in tight spaces was beneficial to facilitating integration. Teamwork was another critical factor in making integration work. “I think you need to have medical, behavioral health and all the departments work as a team, communicating. If you communicate, you work, the work flows” (Manager, Site A). Another element at both sites that improved collegial relations, strengthened the program, and increased the likelihood of referrals being made was having social interactions that allowed participants from various groups to get to know each other whereby “it wasn’t they and we anymore. It was us” (Manager, Site B).

Strong leadership support

Strong leadership support for integration and mental healthcare was another component that respondents report is necessary for integration to succeed. Integration is a difficult and costly process, according to the interviews; it requires fundraising and allocating resources to services, such as mental healthcare, that do not necessarily provide the agencies with a return on their investment. “We’ve actually begun to apply for grants and that sort of thing to get more resources . . . [because] mental health reimbursements are lousy” (Leadership, Site A). This allocation of staff resources to seeking out alternative funding options for mental healthcare indicates a commitment to integration practices at the FQHCs. Difficulties also arise in integrating teams who are used to very different ways of practicing care, and leadership must manage these challenges while being supportive of many different perspectives.

Shared electronic health record

Interviewees stated that a full, shared medical record, protected by the 1996 Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), 52 was an important tool in creating an integrated delivery system that addresses a range of health issues. The absence of a shared electronic health record contributes to fragmentation and separateness, which makes integration more challenging. Providers being able to see whom each patient is interacting with, what medications they take, and what treatment plans they have facilitated integration in a significant way. Integration is most successful when all of a patient’s providers have access to his or her records so that the multidisciplinary team is aware of all physical and mental-health-related issues and can make decisions about patient care while being in possession of all pertinent facts. When records are not shared, sub-optimal patient care may result, including drug interactions and side effects of medications being mistaken for symptoms of other conditions, and it is more difficult for health promotion, adherence, and prevention interventions to occur in mental health visits.

Barriers to integration

Interdisciplinary cultural conflict

The development of a multicultural team poses challenges that can create or reinforce barriers to integrating care. This study found that conflict between the cultures of medicine and mental health was a significant barrier to integration. Indeed, the issue that interviewees at both sites and at all levels reported most often as a barrier to integration was the very complex one of cultural conflict between medical and mental health practitioners. One issue was the difference in theories about how care should be provided. Some mental health providers wanted to engage patients in long-term therapy, whereas medical staff members, who have more control over resource allocation, expected short, effective, efficient interventions. Frontline respondents expressed frustration about the role of management in integrating care with a focus on the medical model—“I think that management focuses on management and not really into the essence of why we’re here” (Frontline Practitioner, Site A).

Differences in professional practice

The varying perspectives on culture provided insight into how agencies function and how differing disciplines interact with each other in integrating physical and mental healthcare. Logistical differences in physical and mental healthcare practices added complexity to integrating care. At both case study sites, medical providers reported being used to a very high-paced job, where they see up to four patients an hour, identifying symptoms and treating those, most likely with medication. There are significant power imbalances between medical doctors and patients, with providers being seen, and seeing themselves, as the experts in the patient’s care.

Mental healthcare traditionally has a very different practice style. Mental health providers typically schedule longer appointments with patients; emphasis in mental healthcare is on developing a therapeutic relationship with patients who are seen as the expert in his or her own life. Mental health providers reported that they worked together with their patients to identify causes as well as symptoms of problems and developed goals to work toward solutions; there tended to be less of a power differential between providers and patients. “My work now is all about the outcome, not the process. We used to have two-hour team meetings to discuss cases. It changed to having to prove I’m doing enough to justify my job” (Mental Health Frontline Practitioner, Site A).

Power differentials and job insecurity

The considerable pressure felt as a result of cultural conflicts, and different practice styles were further compounded by power asymmetry between agency leadership/management and frontline mental health staff. A critical example is the primacy given to the medical model in agency leadership and managements’ views on productivity and success over the views of frontline mental health staff. Leadership spoke of the success of new integration practices as evidenced by increased numbers of patients accessing mental healthcare services. However, this emphasis on productivity rather than patient outcomes was stressful for frontline practitioners, as it was contrary to the discipline’s aforementioned culture of more autonomous, therapeutic relationship building with patients.

Leadership at both sites acknowledged that integration has created a focus on the productivity of frontline mental health workers. Respondents report differing views on the impact that this emphasis on meeting targets had on the integration process. At Site A, frontline workers reported constantly feeling under pressure to meet productivity standards, not necessarily to provide good care. These respondents reported that their stress levels have increased since integration began and that the pressure they experienced shaped their practice, which became focused on meeting targets, rather than improving patient well-being: “the message we got is, ‘if you don’t like it, leave’ and a lot of people did leave” (Frontline Practitioner, Site B). However, these frontline workers feel powerless to subvert agency policy and practices or do anything other than meet their targets; they feel unable to address their concerns about their patients because of their lack of power and their low place in the agency hierarchy.

Frontline workers also reported experiencing financial stress—“We all have second jobs to manage financially because the salaries are so low” (Frontline Practitioner, Site B). Medical leadership representatives did not appear to recognize the pressures on their frontline practitioners, but one mental health leadership representative did acknowledge these challenges: “the salary is a big issue. I understand because most of our staff . . . are working two and three jobs to make ends meet” (Mental Health Leadership, Site A). However, frontline workers expressed not being secure enough in their positions to discuss financial anxieties with agency leadership or management. As a result, financial stress and pressure to meet productivity targets exacerbate frontline worker’s feelings of job insecurity and powerlessness in addressing these concerns with agency leadership.

At Site A, a few interviewees indicated some lack of trust in leadership’s assertions that integration policy is being implemented to improve patient care, within the context of constrained resources. One manager reported that, while integration was a positive move for the center, “I worry sometimes that integrated behavioral health is just a mechanism to really phase out a lot of the services” (Manager, Site A). By reducing time spent with patients in attending to their mental health needs to fit with the medical model, the concern was that behavioral healthcare would no longer be comprehensive and would involve very short-term interactions with patients.

Communication challenges

An important part of the cultural difference between physical and mental healthcare is the communication challenge or language barrier, including the use of medical and psychological terminology and jargon. Medical and mental health practitioners used very different language in talking about patients and providing care, which can create confusion and raise or reinforce barriers to accessing care if it is not addressed. One respondent spoke about the challenges of addressing this barrier and argued that having a social worker as an intermediary to help each side understand the other was the only solution. Said this interviewee: “I think having this social worker in the middle who kind of spoke both languages helped take away the ‘they’ and convert the ‘they’ into us, which I think is absolutely essential for successful integration” (Manager, Site B).

All respondents acknowledged that communication barriers were a problem in integrating care, and the solution was for mental health providers to learn the medical teams’ language and adapt how they communicate to fit the medical model. While all providers are now using the same language, it is the language of the medical team that is in general usage and the language of mental healthcare has been lost.

Subsumption not integration

This case study uncovered widely differing views on how integration policy has been implemented. Significantly, medical staff members considered that integration is working well, the team is cohesive, more referrals are being made to mental healthcare providers, and more patients are following up on these referrals and are accessing care. However, frontline mental health clinicians report that, while more patients are indeed being referred to and are accessing mental health services, the culture of mental healthcare has disappeared. Instead of developing therapeutic relationships with clients, mental healthcare workers report that the focus was now on productivity, with an emphasis on quantity rather than quality of care. “You can’t have the old behavioral health model, even though it’s valuable, in this climate. Behavioral health is not a moneymaker” (Frontline Practitioner, Site B). This individual’s perception was that the impetus for integrating care was financial rather than to truly improve the quality of and access to mental healthcare.

Discussion

Integration with prior work and implications

This article examined the facilitators and barriers to integrating physical and mental healthcare in two case study sites. The integration of physical and mental healthcare is a complex issue with many, often interacting components and there is not one clear, widely adopted definition of integration or related terms.20,53,54 It is clear that there are many definitions of integration within the broader parameters established by the federal government under the PPACA. Thus, because this definition of integration is so broad, agencies have discretion to interpret the federal government’s call for integration along the aforementioned continuum of physical and mental healthcare provision from care coordination, through co-location, to full integration. 55

While staff members at both sites had similar responses when asked about integration, integration meant very different things to different groups within these organizations. The medical staff was very positive about integration; they noted that co-located services, the warm hand-off, and a shared electronic health record are important elements of integrating care. Significantly, medical staff considered that integration had taken place, that the providers work together as a team, and that more patients were accessing mental healthcare. Thus, the medical providers described integration as successful. This aligns with established definitions of primary care behavioral health integration.36,56

It is important to note that these FQHCs measure the success of integration solely by process indicators, such as the numbers of patients accessing mental health services, rather than by improved patient outcomes from the utilization of such services. Despite having metrics and practices in place to assess outcomes for physical health, the same evaluations are not made in mental healthcare. Respondents at the leadership and management levels noted that this was a problem but also noted that they had no current plans to address this problem.

Mental health providers, however, described a rather different experience, with a cultural shift from emphasizing therapeutic relationships and a focus on the patient, to a model of meeting productivity targets, and daily communication dominated by medical terminology, acronyms, and scientific terms that are not readily accessible to non-medical individuals. While mental health providers agreed that more patients are accessing care, their perception was that the medical model has subsumed mental health, rather than integrated with it, thereby limiting the full implementation of physical–mental healthcare integration. Frontline mental health practitioners feel powerless to address these concerns with leadership, as they are fearful of losing their jobs, and, as one such worker noted, frontline staff already are working several jobs to support themselves. Such power differentials also meant that the bottom-up approach is not a factor at these sites, as frontline workers do not have the power, freedom, or discretion to alter policy or practice, and the focus is very much on top-down decision making. Measures and values that are pertinent to mental health providers are not often captured in operational metrics of integration outcomes. 57

This study found both facilitators and barriers to implementing integration policy. The co-location of providers within the same department, a warm hand-off, collaborative collegial relationships, strong leadership support, and a shared electronic health record all facilitate integration. However, interdisciplinary conflict, power differentials and job insecurity, communication challenges, and the subsumption of mental health into the medical model pose barriers to successful integration. In short, all respondents stated that integration had improved access to care, but there were differing thoughts about how this was achieved and if integration had really taken place, or if mental health had merely been subsumed into the medical model. The mental health provider attitude on integration has often highlighted benefits such as improved patient access to services, reduction of mental health stigma, and positives of team-based care: there is limited research on the challenges of integration on mental health provider identity and role diffusion. 58

The issue of cultural conflict in the integration process is important to consider. There are cultural differences between the fields of physical and mental healthcare, and how these differences are perceived and the impact such differences have are vary greatly between physical and mental healthcare providers. A common thread among interviews with frontline practitioners and management in mental healthcare was this struggle between the two disciplines. Interestingly, the primary care providers did not appear to recognize the importance of this conflict, and frontline mental health workers did not report sharing their concerns with the medical team; thus, it is not discussed or addressed. This “stranger in a strange land” sensation may go unmentioned, as the mental health clinician seeks to blend in and assimilate in the primary care setting. 59

Cultural, practice, and linguistic differences between medical and mental health create barriers to working together. Providers on both sides reported that their agencies have worked to overcome these barriers to integrate both teams and styles of practice. However, close analysis of the data indicated that rather than true integration taking place, mental healthcare has been subsumed into the medical model. Advanced levels of integrated care often require practice adaptations by physical health providers, incorporating elements of mental health interventions, perspectives, and practices. 60

This subsumption model, rather than one of equal contribution from the two disciplines, creates another barrier to full integration, as it becomes the established practice of healthcare delivery. This model does not give mental health an equal footing with physical health, therefore maintaining the status quo whereby mental health is lower on the agenda and, as such, receives less attention and resources than physical health.

Agency leadership and management, as well as medical providers, spoke of the changes that have been made within the agencies in the pursuit of care integration. When describing these changes, examples of adaptations to practice were made exclusively by the mental healthcare team. There was no acknowledgment that this may be a problem to consider, nor were there any suggestions that the medical providers make any compromises or changes to their culture to accommodate changes brought about by integration.

Contributions to the field and recommendations

The PPACA sought to promote the integration of mental and physical healthcare in FQHCs to close the chasm in mental health treatment and prevalence in the United States. The findings from this study indicate that there are policy gaps in terms of defining what integration means, providing adequate funding for integration to occur, reporting on integration outcomes, and addressing disparities in service provision where integration takes place. These gaps must be addressed in order to improve patient access to mental healthcare.

This study contributes to the literature on healthcare integration in terms of definitions, practices, and the intersection of policy implementation and integration of physical and mental healthcare. Despite the PPACA having been enacted in 2010, there is a dearth of literature or research in this arena and on examining how integration occurs.

This article makes several policy recommendations, including the development of a clear definition of integration, a complex and challenging process. It is important to provide FQHCs with a roadmap for implementing comprehensive integration successfully in a manner consistent with federal intentions in this area. In addition, policy makers should restructure funding for mental healthcare provision to encourage comprehensive integration.

In terms of suggestions for future research, further inquiry into how integration is being interpreted and applied would add to existing scholarship on the efficacy of integration in improving access to mental healthcare. The subsumption of mental health into the medical model is also worthy of future inquiry not just for patient outcomes but also for frontline mental health practitioners in terms of their own life opportunities. A detailed examination of the role of the hierarchy in agency functions would be helpful in uncovering power differentials between physician and mental health providers and may offer suggestions to address any imbalance in equity and equality between the two disciplines.

Limitations

The research findings offer important insights into the integration of physical and mental healthcare in FQHCs. However, some limitations to this study are acknowledged. First, the research took place in two FQHCs and while assumptions can be made about how they compare to the broader population of agencies, it is impossible to know exactly how similar or dissimilar their policies, practices, and outcomes are to other FQHCs. Therefore, the results of this study are not transferable to all other FQHCs, although they may apply to FQHCs with characteristics similar to the two case study sites studied.

Conclusion

This study found that all organizational staff at every level stated that integration had improved access to care, but there were differing thoughts about how this was achieved and if integration had really taken place, or if mental health had merely been subsumed into the medical model. This study found both facilitators and barriers to implementing integration policy. The co-location of providers within the same department, a warm hand-off, collaborative collegial relationships, strong leadership support, and a shared electronic health record all facilitate integration. However, interdisciplinary conflict, power differentials and job insecurity, communication challenges, and the subsumption of mental health into the medical model pose barriers to successful integration.

The results of this investigation emphasize the importance of alignment of organizational goals, models of delivery, operational processes, and outcome variables within an FQHC to achieve consensus across leadership, management, team leaders, and care staff. Effective bidirectional communication, coordination, and process measurement are based on such alignment and perceived safety and accountability. Effective rollout of integration between mental and physical healthcare involves more than an operational and logistical coordination, but a sizable cultural and philosophical change, especially for mental health providers entering the healthcare environment. This will warrant sensitivity from leadership to balance staff experiences, operational priorities, and organizational mission, and considering outcomes beyond productivity (e.g. satisfaction, improvement in clinical markers, team cohesiveness, degree of mission alignment). Careful organizational consideration to barriers and facilitators of integrated care, engagement of street-level bureaucrats and care staff, and shifting financial paradigms are clear and present take-homes from this analysis.

Appendix 1

Interview guide—practitioners

Interview Number: ______________________________

Date/Time of Interview: __________________________

Place of Interview: _______________________________

Interviewer: ____________________________________

Interviewee Job Title:_____________________________

Consent Form Signed at Interview: YES/NO

- A: Information/questions about the interview

- I am conducting research on the implementation of mental health policy at your Center, and I am interested in the integration of physical and mental healthcare. I am trying to learn more about how this center functions and to discover how integration takes place here. I would like to understand what the successes and difficulties have been. I am very interested in your perspective on how mental health services and programs are provided by this health center. I would also like to hear your views on what has worked and what has been less helpful in the integration process. My objective is to learn from your experience and knowledge. This interview is confidential and any unintentional disclosure of identifying information will not be documented.

- Discuss content and expected length of interview and ask if any questions about the project.

- Ask if any questions about consent, recording, and confidentiality. Sign form.

- B: Questions about interviewees’ position, patient population, and information sharing.

- Can you describe your role in this organization?

- What is your professional background and training?

- How did you come to be in your current position? Can you describe your career path?

- How does communication between you, management, and agency leadership take place?

- What does an average week look like for you?

- According to my research X number of patients are registered at this health center. Do you think this number is accurate? Of those, how many utilize your mental health services and programs?

- What strategies do you use to reach potential patients?

- What materials do patients receive about the mental health programs and services?

- May I have copies of the materials that patients receive?

- C: Questions about service provision and the integration of physical and mental healthcare

- Can you describe the range of treatment and services that are provided at this organization?

- What are the main activities?

- What are the goals of this health center for mental healthcare?

- What mental health services are provided at this center?

- Do you think that the uptake of mental health services reflects actual prevalence in the general population?

- Do you think services reflect actual need in your community?

- D: Questions about the integration of physical and mental healthcare and policy implementation.

- How has the integration of physical and mental health care occurred in this health center?

- Have there been many changes since this integration began?

- Has integration impacted the relative weight or emphasis given to mental health and medical needs?

- Have there been many changes in service provision since integration began?

- Can you describe any factors that have facilitated the integration process?

- Can you describe factors that have impeded the integration process?

- Of these, which are the most significant challenges to the integration process?

- Can you describe how mental health care policy is developed in this organization?

- Do you have input in policy development?

- How effective is this center in implementing policy as devised by the board?

- What problems, if any, do you see in policy implementation?

- Do you have any leeway in your work in how you implement policy?

- Do you have to adapt policy implementation processes to respond to limited resources, demand for services, or other factors?

- E: Questions about perceptions regarding mental illness

- How did you develop your understanding and knowledge of mental illness?

- What are the most important considerations/what influences you when treating clients/patients?

- How do you think society in generally views people living with mental illness?

- What is your view of the media portrayal of mental illness?

(The following question will be asked if the interviewee brings up the issue of stigma. If the interviewee does not mention stigma, the researcher will preface the questions with the following: “In compiling my literature review, I noticed that the issue of stigma and mental illness is a recurring theme. I would be interested to hear your thoughts on this subject.)

Have you witnessed any stigmatizing events/attitudes in this agency?

If so, what was the individual and agency response?

- F: Wrapping Up

- Is there anything else you would like to tell me about the mental health services at this center?

- Is there anything else you would like to discuss further?

- Are there other people at this Center whom you think I should meet with?

- Is there anything you would like to ask me?

- May I contact you again in the future if I have any additional questions?

THANK YOU

Footnotes

Authors’ note: We confirm that this work is original and has not been published elsewhere, nor is it currently under consideration for publication elsewhere.

Author contributions: K.M. contributed to conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, software, supervision, validation, visualization, writing-original draft, and writing-review and editing. T.C. helped in writing-review and editing, and formal analysis.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Karen Monaghan  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0931-4503

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0931-4503

References

- 1. Palpant RG, Steimnitz R, Bornemann TH, et al. The Carter Center Mental Health Program: addressing the public health crisis in the field of mental health through policy change and stigma reduction. Prev Chronic Dis 2006; 3(2): A62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Corrigan PW, Shapiro JR. Measuring the impact of programs that challenge the public stigma of mental illness. Clin Psychol Rev 2010; 30(8): 907–922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Council for Behavioral Health. Mental Health First Aid, 2021, https://www.mentalhealthfirstaid.org/2019/02/5-surprising-mental-health-statistics/

- 4. NIMH. Mental health information, 2021, https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness.shtml

- 5. US Government Printing Office. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 2011, https://www.congress.gov/111/plaws/publ148/PLAW-111publ148.pdf

- 6. Corey G, Corey M, Callanan P. Issues and ethics in the helping professions. 6th ed. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks Cole, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Corrigan P. (ed.) On the stigma of mental illness. Practical strategies for research and social change. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lang AJ. Brief intervention for co-occurring anxiety and depression in primary care: a pilot study. Int J Psychiatry Med 2003; 33(2): 141–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Massachusetts Department of Public Health. Massachusetts Behavioral Health Analysis, 2012, https://www.mass.gov/doc/integration-of-behavioral-health-and-primary-care-0/download

- 10. Brunelle J, Porter R. Integrating care helps reduce stigma. Health Prog 2013; 94(2): 26–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. (eds). Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bodenheimer T, Grumbach K. Understanding health policy: a clinical approach. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). HRSA fact sheet, 2020, https://data.hrsa.gov/data/fact-sheets

- 14. Wright B. Who governs Federally Qualified Health Centers? J Health Polit Policy Law 2013; 38(1): 27–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Improving the quality of health care for mental and substance-use conditions. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Health Connector. Report to the Massachusetts Legislature. Implementation of health care reform, fiscal year 2010, November 2010. https://betterhealthconnector.com/wp-content/uploads/annual-reports/ConnectorAnnualReport2010.pdf

- 17. Possemato K. The current state of intervention research for posttraumatic stress disorder within the primary care setting. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2011; 18(3): 268–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hunter CL, Funderburk JS, Polaha J, et al. Primary Care Behavioral Health (PCBH) model research: current state of the science and a call to action. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2018; 25(2): 127–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Miller-Matero LR, Dykuis KE, Albujoq K, et al. Benefits of integrated behavioral health services: the physician perspective. Fam Syst Health 2016; 34(1): 51–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Reiter JT, Dobmeyer AC, Hunter CL. The Primary Care Behavioral Health (PCBH) model: an overview and operational definition. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2018; 25(2): 109–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Funderburk JS, Shepardson RL, Wray J, et al. Behavioral medicine interventions for adult primary care settings: a review. Fam Syst Health 2018; 36(3): 368–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Possemato K, Johnson EM, Beehler GP, et al. Patient outcomes associated with primary care behavioral health services: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2018; 53: 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kreitner R, Kinicki A, Buelens M. Organizational behaviour. London: McGraw-Hill, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Martin MP, White MB, Hodgson JL, et al. Integrated primary care: a systematic review of program characteristics. Fam Syst Health 2014; 32(1): 101–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wilson JQ. Bureaucracy: what government agencies do and why they do it. New York: Basic Books, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Joniak E. Exclusionary practices and the delegitimization of client voice. Am Behav Sci 2005; 48(8): 961–988. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sabatier P, Mazmanian D. The implementation of public policy: a framework of analysis. Policy Stud J 1980; 8(4): 538–560. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pressman JL, Wildavsky A. Implementation: how great expectations in Washington are dashed in Oakland. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sabatier PA. Top-down and bottom-up approaches to implementation research: a critical analysis and suggested synthesis. J Public Policy 1986; 6(1): 21–48. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lipsky M. Street-level bureaucracy: dilemmas of the individual in public services. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Peters BG, Pierre J. Handbook of public administration. London: SAGE, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Aij KH. Lean leadership health care: enhancing peri-operative processes in a hospital. Doctoral Dissertation, VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gale N, Dowswell G, Greenfield S, et al. Street-level diplomacy? Communicative and adaptive work at the front line of implementing public health policies in primary care. Soc Sci Med 2017; 177: 9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Monaghan KR. Mind the gap: the integration of physical and mental healthcare in Federally Qualified Health Centers. Graduate Doctoral Dissertations, paper 213, 2015, https://scholarworks.umb.edu/doctoral_dissertations/213

- 35. Yin RK. Case study research. Design and methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Peek CJ. Lexicon for behavioral health and primary care integration: concepts and definitions developed by expert consensus (AHRQ publication no. 13-IP001-EF). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2013, https://integrationacademy.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/2020-06/Lexicon.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 37. Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hinshaw SP, Stier A. Stigma as related to mental disorders. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2008; 4: 367–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. deLeon P, deLeon L. What ever happened to policy implementation? An alternative approach. J Public Adm Res Theory J Part 2002; 12(4): 467–492. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hall RH. Organizations: structures, processes, and outcomes. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Handel MJ. The sociology of organizations: classic, contemporary, and critical readings. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Harter JK, Schmidt FL, Asplund JW, et al. Causal impact of employee work perceptions on the bottom line of organizations. Perspect Psychol Sci 2010; 5(4): 378–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Maynard-Moody S, Musheno MC. Cops, teachers, counselors: stories from the frontlines of public service. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Whitford AB. Decentralized policy implementation. Polit Res Q 2007; 60(1): 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Goffman E. Stigma. Notes on the management of spoiled identity. 3rd ed. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Falk G. Stigma: how we treat outsiders. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Schneider A, Ingram H. Social construction of target populations: implications for politics and policy. Am Polit Sci Rev 1993; 87: 334–347. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Steinmo S, Watts J. It’s the institutions stupid! Why comprehensive national health insurance always fails in America. J Health Polit Policy Law 1995; 20(2): 329–372, http://jhppl.dukejournals.org/cgi/reprint/20/2/329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Stuber J, Schlesinger M. Sources of stigma for means-tested government programs. Soc Sci Med 2006; 63(4): 933–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Beehler GP, Funderburk JS, King PR, et al. Using the Primary Care Behavioral Health Provider Adherence Questionnaire (PPAQ) to identify practice patterns. Transl Behav Med 2015; 5(4): 384–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ospina S, Foldy E. Building bridges from the margins: the work of leadership in social change organizations. Leadersh Q 2010; 21(2): 292–307. [Google Scholar]

- 52. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Health information privacy, 2014, http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/index.html

- 53. Vogel ME, Kanzler KE, Aikens JE, et al. Integration of behavioral health and primary care: current knowledge and future directions. J Behav Med 2017; 40(1): 69–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Martinez LS, Lundgren L, Walter AW, et al. Behavioral health, primary care integration, and social work’s role in improving health outcomes in communities of color: a systematic review. J Soc Social Work Res 2019; 10(3): 441–457. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Miller BF, Mendenhall TJ, Malik AD. Integrated primary care: an inclusive three-world view through process metrics and empirical discrimination. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2009; 16(1): 21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Heath BW, Wise Romero P, Reynolds K. A standard framework for levels of integrated healthcare. Washington, DC: SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Miller BF, Talen MR, Patel KK. Advancing integrated behavioral health and primary care: the critical importance of behavioral health in health care policy. In: Talen MR, Burke Valeras A. (eds) Integrated behavioral health in primary care. New York: Springer, 2013, pp. 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Glueck BP. An interpretative phenomenological study of behavioral health clinicians’ experiences in integrated primary care settings. Raleigh, NC: North Carolina State University, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Pomerantz AS, Corson JA, Detzer MJ. The challenge of integrated care for mental health: leaving the 50-minute hour and other sacred things. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2009; 16(1): 40–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Getch SE, Lute RM. Advancing integrated healthcare: a step by step guide for primary care physicians and behavioral health clinicians. Mo Med 2019; 116(5): 384–388. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]