Reactivation of p53 by MDM2 inhibitors potentiates anticancer immune surveillance through derepression of ERVs and dsRNA stress, resulting in induction of the interferon pathway and improved response to checkpoint therapy.

Abstract

The repression of repetitive elements is an important facet of p53's function as a guardian of the genome. Paradoxically, we found that p53 activated by MDM2 inhibitors induced the expression of endogenous retroviruses (ERV) via increased occupancy on ERV promoters and inhibition of two major ERV repressors, histone demethylase LSD1 and DNA methyltransferase DNMT1. Double-stranded RNA stress caused by ERVs triggered type I/III interferon expression and antigen processing and presentation. Pharmacologic activation of p53 in vivo unleashed the IFN program, promoted T-cell infiltration, and significantly enhanced the efficacy of checkpoint therapy in an allograft tumor model. Furthermore, the MDM2 inhibitor ALRN-6924 induced a viral mimicry pathway and tumor inflammation signature genes in patients with melanoma. Our results identify ERV expression as the central mechanism whereby p53 induction overcomes tumor immune evasion and transforms tumor microenvironment to a favorable phenotype, providing a rationale for the synergy of MDM2 inhibitors and immunotherapy.

Significance:

We found that p53 activated by MDM2 inhibitors induced the expression of ERVs, in part via epigenetic factors LSD1 and DNMT1. Induction of IFN response caused by ERV derepression upon p53-targeting therapies provides a possibility to overcome resistance to immune checkpoint blockade and potentially transform “cold” tumors into “hot.”

This article is highlighted in the In This Issue feature, p. 2945

INTRODUCTION

Reinstatement of the major tumor suppressor p53 by genetic means has demonstrated remarkable tumor suppression in animal models, providing strong support for p53 reactivation as a promising anticancer strategy (1–3). Several p53-reactivating agents have been discovered that restore the function of wild-type p53 by targeting its major negative regulators MDM2 or/and MDMX. A number of clinical trials have been initiated recently to test the efficacy and safety of MDM2 inhibitors such as milademetan (DS-3032b), siremadlin (HDM201), idasanutlin (RG7388), and others (for review, see ref. 4). The cell-permeating stapled peptide ATSP-7041 inhibits both MDM2 and MDMX and is highly effective in tumor suppression in vitro and in vivo (5). Its advanced analogue ALRN-6924 is currently being tested in a number of clinical trials, including phase I/II trials, where it is tested as a chemoprotective agent to protect healthy cells in patients with cancers that harbor TP53 mutations to reduce or eliminate chemotherapy-induced side effects (www.clinicaltrials.gov).

In addition to p53 target genes involved in tumor suppression, p53 response elements are found in endogenous retrovirus (ERV)–derived long terminal repeat sequences (LTR), which account for 30% of p53 binding sites in the genome (6, 7). Leonova and colleagues have shown that p53, together with DNMT1, is required for silencing of repetitive elements (8). Several studies have firmly established that p53 plays an important role in inhibiting the expression of repetitive elements, via direct binding and/or cooperation with epigenetic mechanisms. Because the expression of repetitive elements can drive both genomic and chromosomal instability, p53-mediated repression of repetitive elements is regarded as an important component of the role of p53 as a guardian of genome (9).

Several transcription factors and epigenetic modifiers cooperate to prevent ERV expression, apart from p53. These include DNMT1, LSD1, pRB, WIP1, and EZH2, among others (10). However, the detailed mechanisms that mediate the communication between these factors remain unclear.

Notably, growing evidence demonstrates an important consequence of expression of ERVs: induction of IFN response (11, 12). IFNs are needed for effective immune response and are also major regulators of tumor-infiltrating immune cells (13). Induction of ERV expression by genetic or pharmacologic means has triggered a viral mimicry response leading to alterations in the local tumor microenvironment that can boost response to immune checkpoint therapy (11, 12, 14, 15).

Cancer immunotherapy can enhance anticancer immune surveillance by blocking immune checkpoints such as PD-L1, CTLA4, and others (16). Checkpoint inhibitors generate promising clinical data by decreasing the chance of de novo resistance and increasing overall survival in patients with melanoma (17). However, many patients are resistant to anti–PD-1/PD-L1 therapy due to different immunosuppressive mechanisms including dysfunctional T cells and lack of T-cell infiltration and recognition by T cells (18). This creates a need to develop combinations with novel target-specific drugs which can overcome resistance to checkpoint inhibitors.

Although several studies provide compelling evidence that, besides tumor cell killing, p53 can also engage both innate and adaptive antitumor immune response (4, 19, 20), we still have much to learn about the effects of pharmacologically activated p53 on the anticancer immune response.

Our data in cancer cell lines, tumor-bearing mouse models, and patients demonstrate that p53 reactivation by MDM2 inhibitors triggers the ERV–dsRNA−IFN pathway followed by activation of antigen processing and presentation genes, thereby abolishing tumor immune evasion. We thereby show the potential of using p53-activating agents to boost anticancer immune surveillance and overcome resistance to immunotherapies.

RESULTS

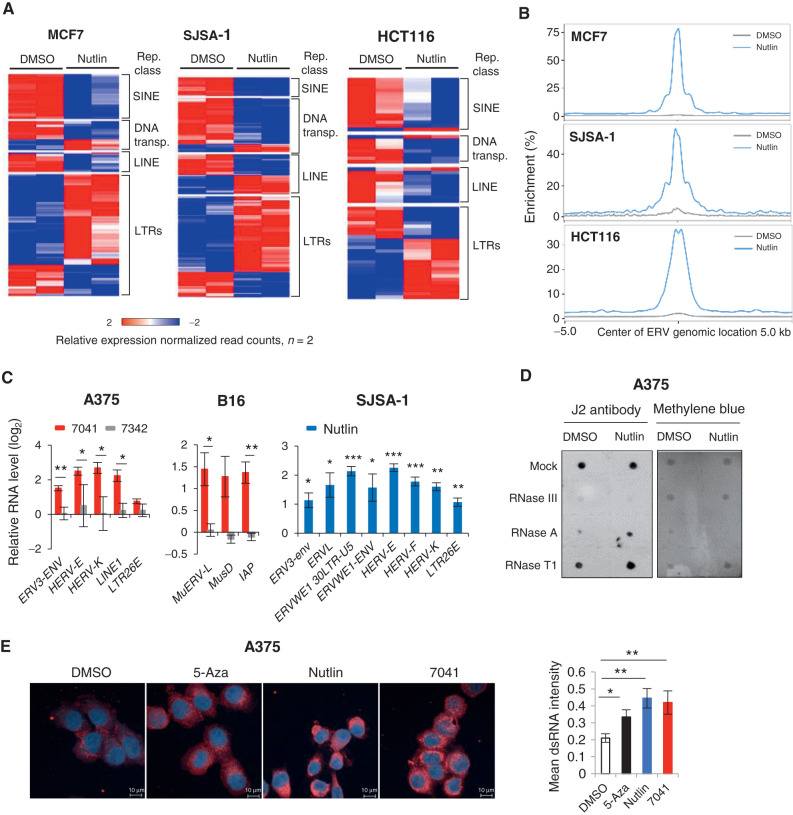

p53 Induces the Expression of ERVs and dsRNA Formation

p53 is recognized as a potent inhibitor of repetitive elements, which contributes to its function as a guardian of the genome (9). We set out to elucidate whether and how pharmacologic activation of p53 will affect the expression of repetitive sequences. Paradoxically, our genome-wide analysis of expression of repetitive elements by nutlin-activated p53 revealed the induction of LTRs, i.e., ERVs, in three wild-type (wt) p53 cancer cell lines of different origin (breast cancer MCF7, osteosarcoma SJSA-1, and colon cancer HCT116) (21). In contrast, the expression of other repetitive elements, SINEs, LINEs and DNA transposons, was mainly repressed (Fig. 1A). Analysis of chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) data revealed a widespread p53 binding to repetitive sequences, including ERVs, induced by nutlin in these cells (Fig. 1B). ChIP-PCR experiment confirmed the increased binding of p53 to the LTR26E promoter, chosen as an example (Supplementary Fig. S1A).

Figure 1.

p53 activation induces ERV expression and dsRNA formation. A, Heat maps show the differential expression of repetitive elements upon p53 activation by nutlin in three different cancer cell lines, as accessed by RNA-seq. B, Increased p53 occupancy on ERVs promoters depicted as average p53 binding score profile mapped onto induced ERVs genome location summits in three different cancer cell lines, as assessed by ChIP-seq. C, ERVs are induced upon p53 activation by 7041 (red bars) and nutlin (blue bars), but not negative control 7342 (gray bars) in A375, B16 and SJSA-1 cells, as assessed by qPCR, n = 3. D and E, dsRNA was induced upon p53 activation by nutlin treatment as detected by dsRNA specific J2 antibody using dot blot (D) or fluorescence microscopy (E). Total RNA was treated with mock, RNase T1, RNase III, or RNase A and blotted on Hybond-N+ membrane. Equal loading visualized by methylene blue staining (D). DMSO was used as a negative control and 500 nmol/L 5-Azacytidine (5-Aza) served as a positive control (E). Student t tests (C, E). Error bars, SD. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

Using qPCR, we validated these results in three wtp53 human cancer cell lines, melanoma A375, MCF7, and SJSA-1, as well as in mouse melanoma B16 cell line. To exclude compound-specific or nonspecific effects of p53 activators, we applied three MDM2 inhibitors, nutlin, AMG232, as well as stapled peptide ATSP-7041 (7041) and its inactive analogue ATSP-7342 (7342), at the following doses: 10 μmol/L of nutlin, 7041, or 7342 and 1 μmol/L of AMG-232. We found an increased expression of multiple human ERVs, such as HERV-K, HERV-E families and others, as well as LINE1, the most abundant LINE in humans, upon p53 activation in these cells (Fig. 1C; Supplementary Fig. S1B and S1C). Similarly, the murine orthologous ERV genes MuERV-L, MusD, and IAP were induced in B16 cells (Fig. 1C; Supplementary Fig. S1B). We confirmed the p53 dependence of ERV induction in p53-null MCF7, SJSA-1, and A375 cell lines, generated using CRISPR/Cas9 or Cas12a gene editing (Supplementary Fig. S1B and S1C).

Next, we applied the J2 antibody which specifically recognizes dsRNA to determine whether ERV transcription leads to the formation of dsRNA. We found an increased dsRNA level after treatment with nutlin in two cell lines (Fig. 1D; Supplementary Fig. S1D). The specific increase of dsRNA, but not ssRNA, was revealed upon treatment with ssRNA-specific RNase A and RNase T1, which degraded ssRNA, but not dsRNA, while RNase III degraded both RNA types, as expected (Fig. 1D; Supplementary Fig. S1D). These results were confirmed by fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry (Fig. 1E; Supplementary Fig. S1E). 5-Azacytidine (5-Aza) served as a positive control for the induction of dsRNA detected by fluorescence microscopy (11, 22). Accordingly, both sense (3.2-fold) and antisense (2.9-fold) ERV-K transcripts were induced upon p53 activation (Supplementary Fig. S1F).

We assessed the contribution of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors, shown previously to induce ERV expression (14), and found that encoded by Cdkn1a p21 depletion did not significantly affect ERV induction by p53 (Supplementary Fig. S1G). Moreover, we found that in addition to target-specific compounds, the chemotherapeutic drug doxorubicin induced the expression of some ERVs in a p53-dependent manner (Supplementary Fig. S1H). Taken together, our findings demonstrate that pharmacologically activated p53 induces the expression of ERVs followed by generation of dsRNA.

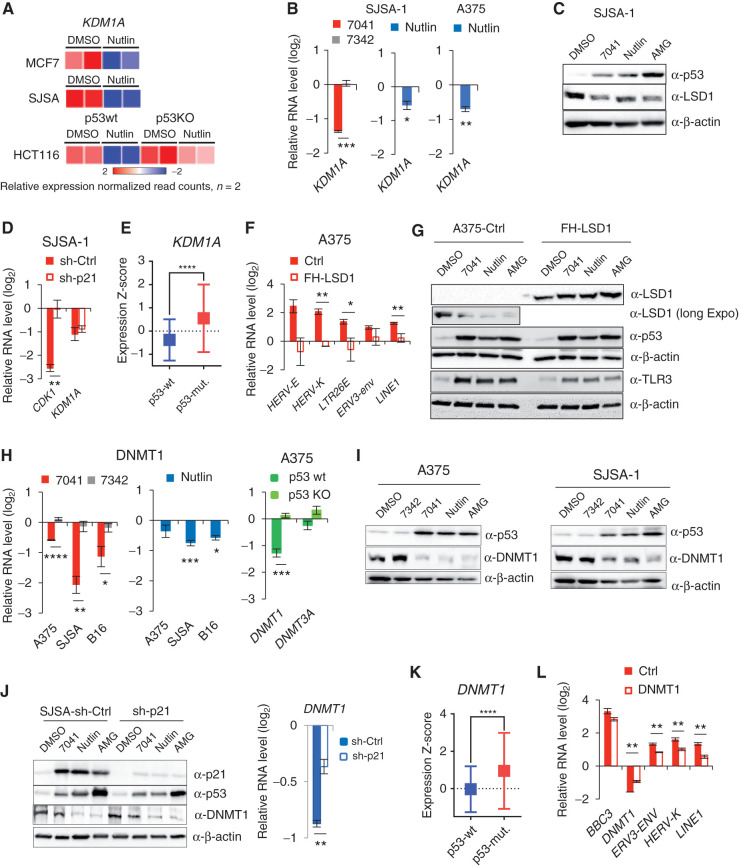

Inhibition of LSD1 and DNMT1 by p53 Releases Silencing of ERVs

Our finding that p53 activates the transcription of ERVs is in contrast to previously reported p53-dependent repression of repetitive elements (8). We set out to investigate the mechanism by which p53 activation derepresses ERV expression. ERVs are the direct targets of transcriptional repression by histone demethylase LSD1. Inhibition of LSD1 has been shown to induce ERV expression and IFN response (15). Therefore, we tested whether LSD1 is involved in p53-mediated derepression of ERVs. Analysis of RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) data revealed an inhibition of KDM1A gene encoding LSD1 upon p53 activation by nutlin in three wtp53 cell lines, but not in p53 knockout (p53KO) line (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, we found that KDM1A was repressed upon p53 activation on mRNA and protein level in a p53-dependent manner (Fig. 2B and C; Supplementary Fig. S2A).

Figure 2.

Inhibition of KDM1A (LSD1) and DNMT1 by p53 mediates the induction of ERVs. A, Heat map shows the inhibition of expression of KDM1A gene encoding LSD1 upon treatment with nutlin in three wtp53, but not in p53-null, cell lines, as detected by RNA-seq. B and C, Inhibition of KDM1A upon p53 activation by compounds on mRNA (A) and protein (B) levels, as assessed by qPCR (A) and immunoblotting (B). D, Depletion of p21 by shRNA does not prevent the inhibition of KDM1A expression by p53, as assessed by qPCR in cells transfected by control shRNA and p21 shRNA and treated with 7041. CDK1 is used as positive control of p21-dependent gene. E, Box plots depict higher levels of expression of KDM1A gene in breast tumors harboring mutant p53 compared with wild-type ones. RNA-seq data are from TCGA. Relative expression values are presented as mRNA expression Z-scores (Mann–Whitney test; ****, P ≤ 0.0001). F and G, Overexpression of LSD1 prevented the induction of repetitive elements by p53 as assessed by qPCR (F) in cells transfected with control vector and FH-LSD1 encoding vector (protein level shown in G), upon treatment with 7041. H and I, Inhibition of DNMT1 upon p53 activation by 7041 (red), nutlin (blue), or AMG232 (green) on mRNA (H) and protein (I) levels, as assessed by qPCR (H) and immunoblotting (I). J, Repression of DNMT1 upon p53 activation by MDM2 inhibitors is largely p21-independent, as detected upon p21 depletion by shRNA in SJSA-1 cells by immunoblot (left) and qPCR (right). K, Box plots depict higher levels of expression of DNMT1 in breast tumors harboring mutant p53 compared with wild-type ones. For the analysis RNA-seq data from TCGA was used. Relative expression values are presented as mRNA expression Z-scores, (Mann–Whitney test; ****, P ≤ 0.0001). L, Partial rescue of p53-dependent induction of ERVs in A375 cells overexpressing DNMT1 upon treatment with 7041. B, D, F, H, J, L, Student t tests. Error bars, SD. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; #, P < 0,0001, n = 3.

p53-mediated repression is often indirect and is mediated by p21 (23). We ruled out the involvement of p21 in the repression of KDM1A, as it was still repressed in p21-depleted cells (Fig. 2D). Notably, analysis of gene expression in human tumors from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) revealed an increased expression of KDM1A in breast cancers harboring mutant TP53 (Fig. 2E) compared to wtp53 tumors, supporting the notion of p53-mediated repression of LSD1. Inhibition of LSD1 plays a role in p53-mediated induction of ERVs, since ectopic expression of LSD1 significantly prevented the induction of ERV genes upon p53 activation (Fig. 2F and G; Supplementary Fig. S2B).

It has been found previously that inhibition of DNMT1 by 5-azacytidine induces the expression of ERVs and dsRNA production (11, 12). p53 has been shown to repress DNMT1 in an SP1- and/or p21-dependent manner (24–26). Consistent with these results, MDM2 inhibitors significantly reduced DNMT1 mRNA and protein levels in human and mouse cells (Fig. 2H and I; Supplementary Fig. S2C). We observed only a partial rescue of DNMT1 mRNA expression upon p21 depletion (Fig. 2J, right), which was not confirmed at protein level (Fig. 2J, left). Further evidence on p53-mediated repression of DNMT1 came from the analysis of the TCGA data demonstrating lower DNMT1 expression in wtp53 tumors compared with p53-mutant tumors (Fig. 2K). We overexpressed DNMT1 to test the impact of DNMT1 in ERV induction by p53 (Supplementary Fig. S2D). The ectopic expression of DNMT1 did not abrogate p53-mediated induction of its target gene PUMA, but significantly attenuated the induction of ERVs (Fig. 2L), suggesting a prominent role of DNMT1 in this process.

To get insight into the mechanism of p53-mediated repression of KDM1A and DNMT1, we tested several factors. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S2E, depletion of activator of KDM1A expression c-Myc, known to be repressed by p53 (27), did not rescue KDM1A and DNMT1 downregulation (Supplementary Fig. S2E). Similarly, miRNAs did not play a role in p53-mediated repression of KDM1A and DNMT1, as defective miRNA processing in DICER-negative cells did not alter their repression (Supplementary Fig. S2F). We therefore reasoned that long noncoding RNAs (lncRNA) regulated by p53 might be involved (28). We tested three lncRNAs and found that silencing of lncp21 and lncPvt1 did not affect p53-mediated repression of KDM1A and DNMT1 (Supplementary Fig. S2G and S2H). However, knockdown (KD) of lncTUG-1 rescued the expression of both KDM1A and DNMT1 upon nutlin treatment in SJSA and MCF7 cells (Supplementary Fig. S2I), indicating its involvement.

The induction of ERVs followed the pattern of time- and dose-dependent inhibition of both LSD1 and DNMT1 on protein and mRNA level, which in turn correlated with p53 accumulation and p21 activation (Supplementary Fig. S2J–S2O). These data lend further support to the notion that inhibition of LSD1 and DNMT1 by p53 leads to ERVs' derepression.

Notably, doxorubicin treatment, which we found to induce ERVs in a p53-dependent manner, also resulted in repression of DNMT1 and LSD1 on protein and mRNA level only in wtp53 cells (Supplementary Fig. S2P and S2Q). We thus conclude that p53-mediated repression of ERV inhibitors LSD1 and DNMT1 is centrally involved in ERV induction.

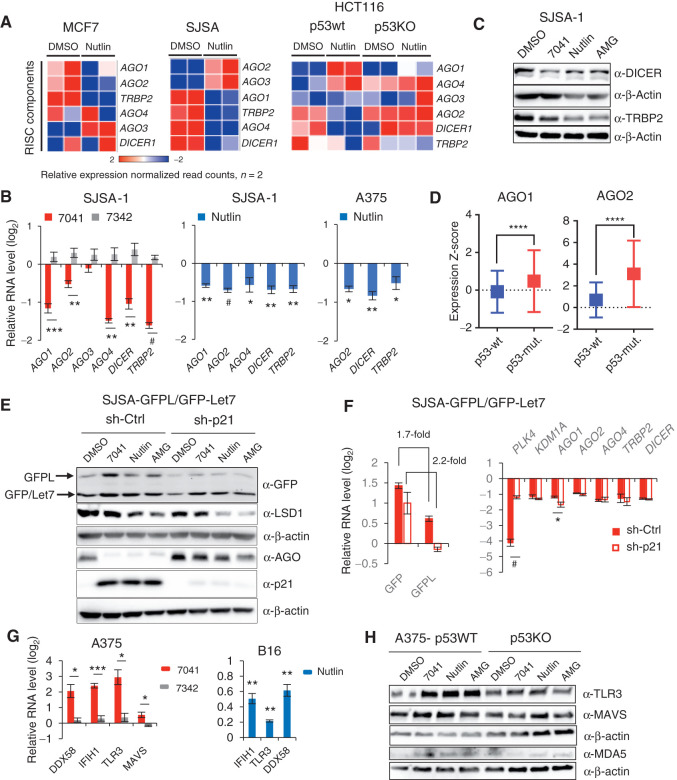

Repression of RISC Components by p53

p53-mediated derepression of ERVs led to the formation of dsRNA (Fig. 1D and E). The dsRNA produced in cells either triggers the IFN response or becomes processed by the RISC components, including DICER and AGO proteins (15). Thus, the steady-state level of dsRNA is determined by its formation versus its processing by RISC, consisting of dsRNA-specific endonuclease DICER, a dsRNA binding protein TRBP, and Argonaute (AGO) proteins. Transcriptome analysis revealed the p53-dependent downregulation of several members of RISC complex, including DICER, TRBP2, and several AGO proteins (variable, depending on cell line; Fig. 3A). qPCR results confirmed the p53-dependent repression of genes encoding RISC components DICER, AGO2, and TRBP2 upon p53 activation by MDM2 inhibitors (Fig. 3B; Supplementary Fig. S3A). Consistent with qPCR data, we detected decreased protein levels of TRBP2 and, partially, DICER upon p53 activation (Fig. 3C). Notably, analysis of TCGA data revealed higher expression of RISC factors AGO1 and AGO2 in breast cancers harboring mutant p53 (Fig. 3D) compared with wtp53 tumors. These data lend further support to the notion of p53-dependent negative regulation of RISC genes.

Figure 3.

Inhibition of dsRNA processing genes and RNA-silencing complex (RISC) activity and induction of dsRNA sensors upon p53 activation. A, Heat maps demonstrating downregulation of RISC genes upon p53 activation by nutlin in three cancer cell lines, as assessed by RNA-seq. B, Immunoblot analysis depicts downregulation of DICER and TRBP2 after p53 activation by 7041, nutlin, or AMG-232 in SJSA-1 cells. C, Genes encoding RISC components are repressed after p53 activation by 7041 (red bars) and nutlin (blue bars) in SJSA-1 and A375 cells, as assessed by qPCR (n = 3). D, Box plots depict higher levels of expression of AGO1 and AGO2 genes in breast tumors harboring mutant TP53 compared with wild-type ones. RNA-seq data are from TCGA. Relative expression values are presented as mRNA expression Z-scores (Mann–Whitney test; ****, P ≤ 0.0001). E and F, Inhibition of RISC activity upon p53 activation by nutlin, 7041, and AMG-232 is largely p21-independent. The expression of GFPL and GFP was measured by immunoblot (E) and real-time qPCR (F) in SJSA-1 cells stably expressing dual reporters GFPL/GFP-let-7 and transduced with scrambled shRNA or p21 shRNA. E, Immunoblotting of LSD1 and AGO proteins (detected by pan-AGO antibody) upon p53 activation in the presence or absence of p21. F, p21-independent repression of RISC genes after p53 reactivation by 7041 (red bars), as assessed by qPCR (n = 3). G, dsRNA receptors are induced upon p53 activation by 7041 (red bars) and nutlin (blue bars) in A375 and B16 cells, as assessed by qPCR, n = 3. H, Induction of TLR3, MDA5, and MAVS in a p53-dependent manner in A375 cells after p53 activation by three MDM2 inhibitors, as detected by immunoblot. β-Actin was used as loading control. B, F, G, Student t tests. Error bars, SD. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; #, P < 0,0001, n = 3.

Next we addressed the question of whether the functionality of RISC upon p53 activation was decreased by measuring the level of a GFP reporter whose expression is under control of RISC-dependent let7 miRNA (29). Activation of p53 by MDM2 inhibitors resulted in elevated expression of the RISC-dependent GFP reporter at mRNA and protein level (Fig. 3E and F; Supplementary Fig. S3B–S3E), suggesting a compromised activity of RISC. RNAi assays indicated that p21 does not play a role in the inhibition of RISC gene expression by p53 nor in reduced activity of RISC (Fig. 3E and F; Supplementary Fig. S3B–S3E). In line with previously shown regulation of the expression of RISC components by LSD1 (15), we found that LSD1 repression contributed to the decreased expression of RISC genes, as evidenced by the partial rescue of RISC genes by LSD1 overexpression (Supplementary Fig. S3F). Repression of RISC genes followed the pattern of DNMT1 and LSD1 downregulation and ERV activation, reaching its maximum after 16 hours of treatment and 10 μmol/L of 7041 (Supplementary Fig. S3G and S3H). In addition, doxorubicin treatment resulted in repression of RISC complex genes in a p53-dependent manner (Supplementary Fig. S3I).

Induction of dsRNA Sensors upon p53 Activation

Intracellular dsRNAs are recognized by endosomal and cytosolic RNA sensors, pattern recognition receptors TLR3, MDA5 (encoded by IFIH1)/MAVS, and RIG-I (encoded by DDX58), which in turn trigger the IFN response (30). Thus, we tested whether the expression of dsRNA receptor(s) was affected by p53 activation. We found that the expression of dsRNA receptors DDX58, IFIH1, TLR3, and MAVS was upregulated by MDM2 inhibitors in a p53-dependent fashion (Fig. 3G, left; Supplementary Fig. S3J). Consistently, the protein levels of TLR3 and MAVS were also induced (Fig. 3H; Supplementary Fig. S3K), while the levels of short dsRNA sensor RIG1 and dsDNA sensor c-GAS were not significantly affected (Supplementary Fig. S3L). The expression of murine orthologous genes IFIH1, TLR3, and DDX58 in B16 cells was also increased (Fig. 3G, right). The chemotherapeutic drug doxorubicin induced several dsRNA sensors, while only TLR3 induction was p53-dependent, which is in line with the induction of DNA damage by doxorubicin (Supplementary Fig. S3M).

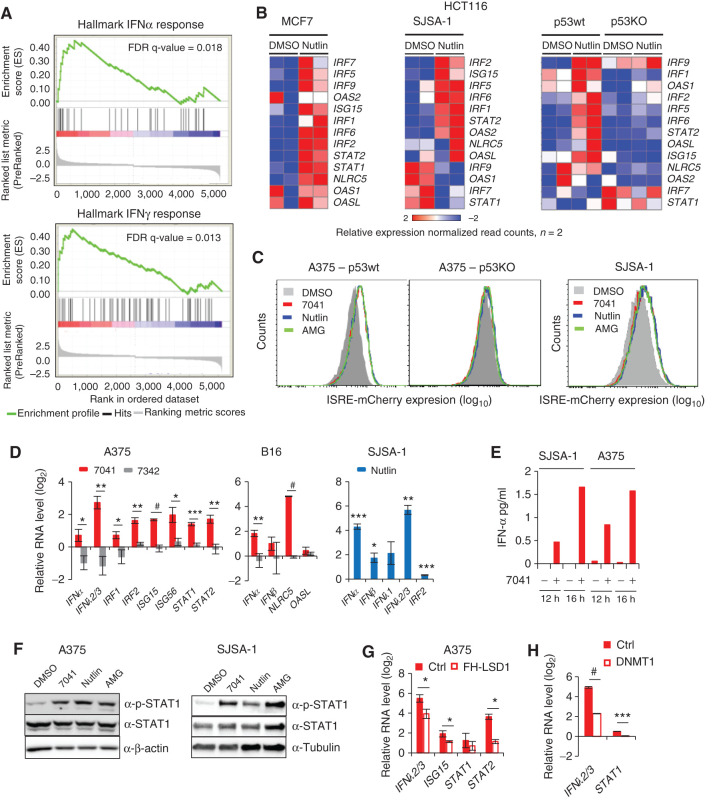

Induction of a Viral Mimicry Response by p53 Is Dependent on LSD1 and DNMT1 Repression

The IFN pathway is a crucial defense response against viral infections. It is triggered by viral dsRNA through cytosolic dsRNA sensors (13, 30). We reasoned that p53-mediated induction of dsRNA stress might induce the IFN response. Pathway analysis of RNA-seq data identified inflammatory response and IFN response among the top 10 most significant pathways induced by nutlin (Supplementary Fig. S4A). Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) revealed the enrichment of upregulated genes involved in IFNα and IFNγ responses after activation of p53 by nutlin in MCF7 cells (Fig. 4A). We found several IFN-regulatory factor genes (IRF) and IFN-stimulated genes (ISG) to be upregulated by nutlin in a p53-dependent manner, as shown in heat maps in Fig. 4B. In line with these data, 7041, nutlin, and AMG232 activated the IFN-responsive mCherry reporter gene in a p53-dependent manner (Fig. 4C; Supplementary Fig. S4B).

Figure 4.

Induction of IFNs and IFN pathway by p53 is LSD1- and DNMT1-dependent. A, GSEA reveals induction of IFNα and IFNγ response genes upon p53 activation by nutlin. B, Heat maps show the induction of IFN regulatory transcription factors (IRF) and IFN-stimulated genes in MCF7, SJSA-1, and p53WT, but not in p53KO HCT116 cells after nutlin treatment, as assessed by RNA-seq. C, IFN reporter gene (ISRE)-mCherry expressed under control of IFN-sensitive response element is induced after p53 activation by three MDM2 inhibitors in p53-proficient but not in p53-deficient cells. D, IFNs, IRFs, and ISGs are induced upon p53 activation by 7041 (red bars) and nutlin (blue bars) in A375, B16, and SJSA-1 cells, as assessed by qPCR, n = 3. E, Induction of IFNα after p53 activation by stapled peptide 7041 in SJSA-1 and A375 cells, as detected by ELISA. F, Induction of phospho-STAT1 levels after p53 activation by three MDM2 inhibitors in A375 and SJSA-1 cells, as assessed by immunoblotting. G and H, Overexpression of LSD1 (G) or DNMT1 (H) partially rescues the induction of IFN pathway genes by p53, as assayed by qPCR in cells transfected with FH-LSD1 or DNMT1 expressing vectors upon treatment with 7041. D, G, H, Student t tests. Error bars, SD. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; #, P < 0.0001.

We found that the mRNA expression of both type I and type III IFNs was increased in different cell lines in a p53-dependent manner (Fig. 4D; Supplementary Fig. S4C–S4E). Accordingly, we detected the induction of IFNα protein upon p53 activation (Fig. 4E).

Following IFN induction, IFN signaling pathway genes, in particular IRF1 and IRF2, ISG15 and ISG56, and STAT1 and STAT2, were upregulated at mRNA level by p53 (Fig. 4D; Supplementary Fig. S4C–S4E). Interestingly, we could not detect IRF9 and IRF5 induction, previously suggested to be p53 targets (31). According to ChIP-seq data, the only upregulated IFN pathway gene whose promoter was bound by p53 in all three cell lines was TLR3, confirming it being a direct p53 target (Supplementary Table S1). Therefore, we conclude that the induction of IFN pathway genes by p53 was mainly indirect. Consistent with mRNA induction, we observed an increased protein expression of pSTAT1 and type I IFN receptor α upon p53 activation by MDM2 inhibitors (Fig. 4F; Supplementary Fig. S4F). Depletion of p21 did not affect the induction of IFNs and pSTAT1 (Supplementary Fig. S4G and S4H), in line with our results mentioned above.

Importantly, the induction of the IFN response was dependent on p53-mediated inhibition of ERV regulators LSD1 and DNMT1. The ectopic expression of LSD1 or DNMT1 significantly attenuated the induction of IFNs and IFN-related genes (Fig. 4G and H; Supplementary Fig. S4I and S4J). Doxorubicin also induced IFNs, in line with previously published data (32). Notably, the induction of IFNλ2/3 and some IFN-related genes by doxorubicin was p53-dependent (Supplementary Fig. S4K).

p53 Activation Enhances Antigen Processing and Peptide Presentation

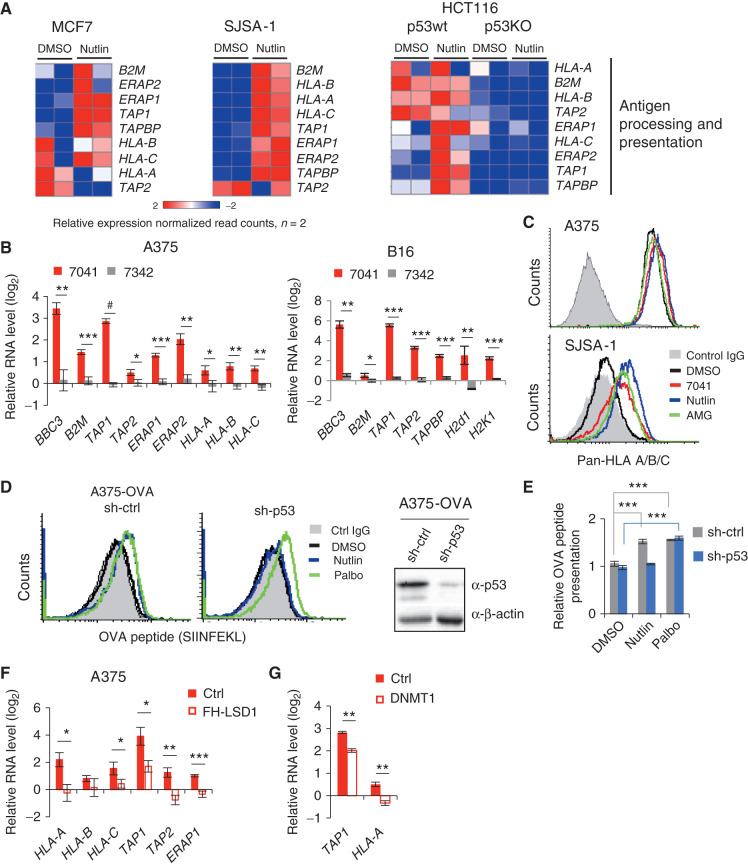

Antigen processing and presentation (APP) by MHC class I molecules is critical for immune surveillance. It is well established that APP genes are downstream targets of the IFN pathway (13, 33). Our GSEA identified a significant impact of p53 on expression of genes involved in inflammatory response (Supplementary Fig. S5A). Analysis of RNA-seq data showed that APP-associated genes were upregulated by nutlin, as shown in heat maps in Fig. 5A. This effect was p53-dependent, because it was lost in HCT116 p53KO cells (Fig. 5A, right).

Figure 5.

Activation of p53 in cancer cells enhances antigen processing and presentation. A, Heat maps show the induction of APP genes in MCF7, SJSA-1, and HCT116 cells, as assessed by RNA-seq. Absence of induction of APP genes in HCT116 p53KO cells confirms p53 dependency. B, qPCR shows the induction of APP genes in melanoma cells A375 (left) and B16 (right) upon treatment with p53-activating stapled peptide 7041 (red bars), but not control peptide 7342 (gray bars). Results shown are the mean ± SD from three independent experiments performed in triplicate (comparison between peptides vs. DMSO treatment). C, Flow cytometry shows an increased cell surface expression of HLA-A/B/C upon treatment with three MDM2 inhibitors in A375 (top) and SJSA-1 cells (bottom). Shown is propidium iodide–negative (PI−) population. D and E, p53-dependent enhanced presentation of heterologous OVA peptide-SIINFEKL on the cell surface of A375-OVA cells upon nutlin treatment, as assessed by flow cytometry (n = 3). DMSO was used as a negative control, palbociclib (Palbo) served as a positive control. F, Overexpression of FH-LSD1 prevented the induction of APP genes upon p53 activation, as assessed by qPCR in A375 cells transfected with FH-LSD1 expression vector and treated with 7041 versus control vector-transfected cells. G, Partial rescue of APP genes induction upon by ectopic expression of DNMT1, assessed as in F. B, E, F, G, Student t tests. Error bars, SD. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; #, P < 0.0001.

We found that the genes encoding MHC class I molecules B2M, HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C were upregulated in A375 cells upon p53 activation by 7041, but not control peptide 7342. 7041 treatment induced genes encoding peptide transporters TAP1 and TAP2, and peptide cleavage ERAP1 and ERAP2 (Fig. 5B, left). Induction of these genes was p53-dependent, because we did not observe it in p53-null A375p53KO cells (Supplementary Fig. S5B). Orthologous APP genes were induced by MDM2 inhibitors in murine B16 cells (Fig. 5B, right; Supplementary Fig. S5C). Similarly, p53-activating compounds nutlin and AMG232 induced APP-associated genes in a p53-dependent manner in diverse cancer cell lines (Supplementary Fig. S5C and S5D). Consistent with qPCR data, MDM2 inhibitors increased MHC class I cell surface expression in a p53-dependent manner (Fig. 5C; Supplementary Fig. S5E).

To verify the functional consequences of increased expression of APP genes, we tested the presentation of heterologous MHC class I–bound peptide SIINFEKL, derived from chicken ovalbumin (OVA). Treatment with nutlin induced the cell surface presentation of OVA peptide in wtp53 OVA-transfected A375 cells, but not in p53-depleted cells (Fig. 5D and E). The CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib, serving as a positive control (14), induced OVA presentation irrespective of p53 status (Fig. 4D and E). Similarly, we detected the upregulation of MHC class I–bound SIINFEKL peptide in murine B16-OVA cells (Supplementary Fig. S5F). Doxorubicin induced APP genes as well, several of them in a p53-dependent manner (Supplementary Fig. S5G). Because CDK inhibitors can induce APP genes (14), we tested the contribution of CDK inhibitor p21. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S5H, p21 depletion did not significantly prevent the p53-mediated induction of the APP genes. In contrast, ectopic expression of LSD1 and DNMT1 partially prevented the induction of APP genes (Fig. 5F and G). This is consistent with the role of LSD1 and DNMT1 in the induction of ERVs and IFN response by p53.

Taken together, our results demonstrate that inhibition of LSD1 and DNMT1 by p53, leading to ERV derepression and dsRNA stress, is involved in the activation of viral mimicry response and antigen processing and presentation pathway in cancer cells.

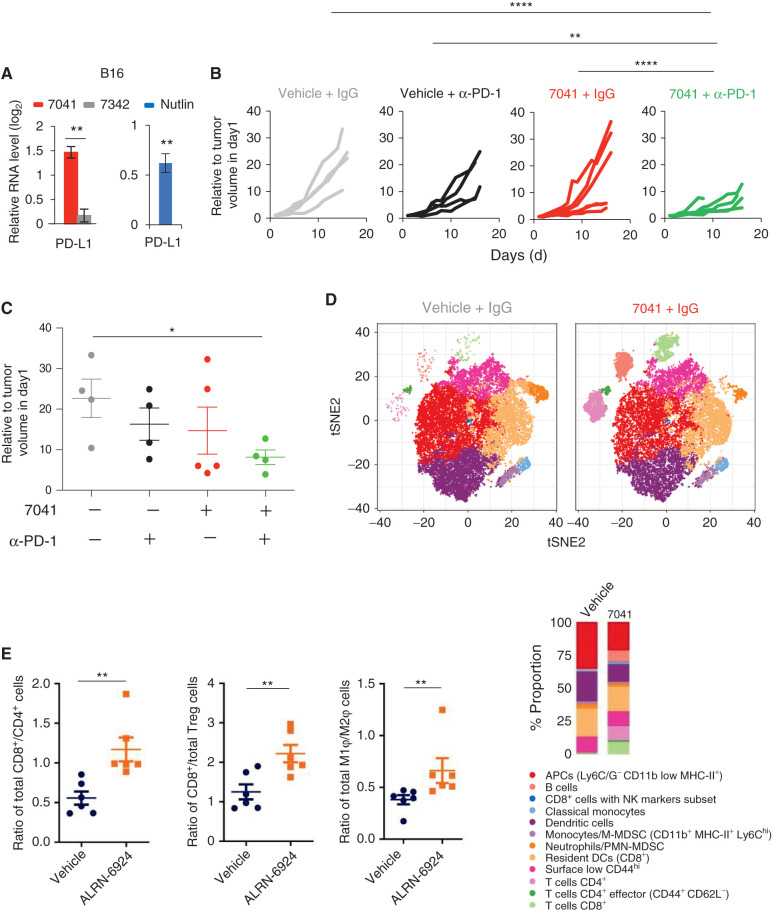

Pharmacologic Activation of p53 Overcomes Tumor Resistance to Checkpoint Blockade

On the basis of our in vitro results that p53 can stimulate cellular pathways related to anticancer immune response, we next determined whether p53 activation will trigger antitumor immunity in vivo. Importantly, our in vitro data suggested an induction of PD-L1 upon treatment with MDM2 inhibitors in mouse melanoma, which can potentially synergize with checkpoint inhibitors (Fig. 6A). While p53 is not a direct regulator of PD-L1, MDM2 inhibitors have been shown to induce PD-L1, most likely indirectly via the IFN pathway (34, 35).

Figure 6.

Pharmacologic reactivation of p53 enhanced T-cell infiltration and overcame tumor resistance to PD-1 blockade in vivo. A, Upregulation of PD-L1 expression upon p53 activation by 7041 or nutlin in B16 melanoma, as assayed by qPCR (n = 3). B and C, Tumor growth (B) and endpoint tumor volume (C) of B16 tumors grown in immunocompetent mice treated with vehicle, 7041, anti–PD-1 antibody, or 7041/anti–PD-1 combination. D, tSNE plot depicting 12 identified immune cell populations (panel below). Each plot represents the merged population of two different tumors per treatment. Bar plots are showing the differential proportion of each cell population in tumors treated with vehicle or 7041. E, Increased infiltration of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and tumor-suppressive M1 macrophages in vivo in colon carcinoma model Colon26 upon treatment with stapled peptide MDM2 inhibitor ALRN-6924, as assessed by flow cytometry. Data are presented as a ratio representing total cell counts where Student t tests (A, E) and one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction (C). Error bars, SD. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

Therefore, we reasoned that p53-mediated enhancement of tumor immunogenicity might sensitize otherwise resistant tumors to checkpoint blockade therapy. We interrogated this possibility using a syngeneic poorly immunogenic B16 mouse model, known to be nonresponsive to PD-L1 blockade in the absence of vaccination (36). As expected, α-PD-1 antibody alone had weak, if any, effect on B16 tumor growth, as did a subtherapeutic dose of 7041. Importantly, when it was administered together with p53 activation by 7041, PD-1 blockade markedly reduced tumor growth in the absence of toxic effects (Fig. 6B and C; Supplementary Fig. S6A).

To understand the effects of p53 activation on immune cell infiltration, we immunophenotyped tumors using single-cell mass cytometry (cytometry by time-of flight, CyTOF). We identified the immune cell populations according to the expression of several clusters of cell surface markers. We analyzed simultaneously 19 markers discriminating initially 20 subpopulations (Supplementary Fig. S6B), which were subsequently clustered into 12 subpopulations (Fig. 6D). p53 activation by 7041 enables a proinflammatory tumor microenvironment, as evidenced by the markedly increased infiltration of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, T-cell CD4+ effector markers, as well as B cells, and decreased number of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC) in the tumors. We did not detect an obvious change in immune cell populations in the spleen upon MDM2 inhibitor (Supplementary Fig. S6C). Furthermore, we found that the treatment leads to the infiltration of active T cells, as judged by the substantially increased expression of Granzyme B detected by IHC (Supplementary Fig. S6D).

We found that the infiltration of immune cells and sensitization to checkpoint therapy was associated with the induction of IFN-related immune response genes in B16 tumors. qPCR analysis of tumor samples revealed the induction of mouse ERVs, dsRNA sensor MAVS, type I and type III IFN and IFN-sensitive gene ISG56 upon p53 activation by 7041 in vivo (Supplementary Fig. S6E–S6G).

Furthermore, we found that the MDM2/MDMX inhibitor ALRN-6924, an advanced analogue of ATSP-7041, caused a significant alteration of immune cell populations and promoted tumor infiltration of immune cells in another mouse model. Treatment of Colon26 allografts with ALRN-6924 resulted in recruitment of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL), in particular cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, as well as an increased number of tumor-suppressing M1 macrophages (Fig. 6E; Supplementary Table S2). We found a significantly decreased tumor growth kinetics upon treatment with ALRN-6924 and a trend for complementary, but not statistically significant, antitumor effect for ALRN-6924 + αPD-1 (Supplementary Fig. S6H). While the potentiation of checkpoint inhibitor therapy is not as striking in this model as in the B16 melanoma model, it shows cooperation that correlates with chemotaxis of immune cells to the tumor environment.

Taken together, our findings demonstrate that pharmacologically activated p53 can boost antitumor immune response and overcome resistance to checkpoint therapy in vivo.

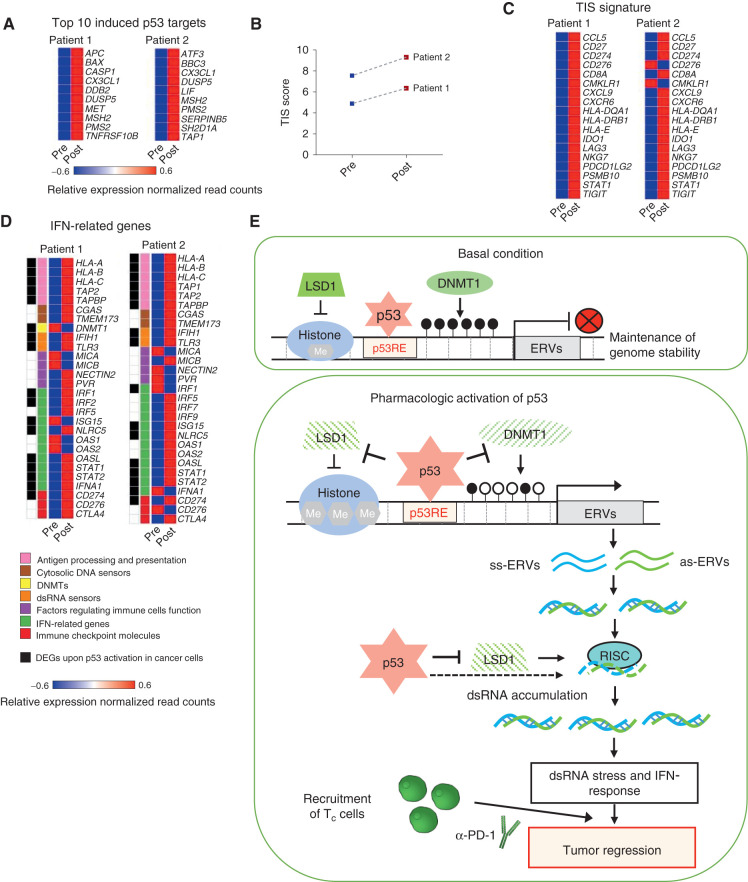

MDM2 Inhibitor ALRN-6924 Induces Intratumoral IFN Response in Patients

To validate our preclinical findings in patients, we analyzed gene expression in pre- and posttreatment biopsy samples from two patients with melanoma enrolled in a clinical trial of ALRN-6924 (37). The first melanoma patient received 4.4 mg/kg ALRN-6924 on days 1, 8, and 15 of a 28-day cycle, while the second patient received 2.0 mg/kg ALRN-6924 on days 1, 4, 8, and 11 of a 21-day cycle. We performed gene expression analysis in tumor biopsies taken before the start of treatment and after two cycles of ALRN-6924 therapy using NanoString PanCancer IO360 and Immune Profiling. First, we assessed whether p53 was activated in patient tumors by the treatment. Indeed, several p53 target genes were induced (Fig. 7A; Supplementary Fig. S7A), indicating p53 activation. Pathway analysis of the PanCancer IO360 genes that were differentially expressed in patient tumors upon treatment revealed highly statistically significant induction of the “Lymphoid” pathway, as well as the IFN pathway (Supplementary Fig. S7B). Next, we compared the expression of Tumor Inflammation Signature (TIS) genes (38) in pre- and posttreatment cancer biopsies. Our analysis revealed the induction of TIS genes, including CD8+ T-cell markers, enzymes of cytotoxic immune cells, chemokines known to increase recruitment of immune cells, and immune checkpoints, including CD274 encoding PD-L1, in both patients (Fig. 7B and C).

Figure 7.

Induction of IFN pathway and immune-related genes in patients with melanoma enrolled in ALRN-6924 clinical trial. A, Heat map showing top 10 induced p53 target genes in tumor biopsies of patients with melanoma enrolled in ALRN-6924 clinical trial, as assessed by NanoString. B, Dot plot depicting the induction of Tumor Inflammation Score (TIS) in patient tumors upon treatment with ALRN-6924. C, Heat map showing the induction of expression of the 18 TIS genes in tumor biopsies from patients pre- and post-ALRN-6924 treatment. D, Heat map representing the differentially expressed IFN- and immune-related genes in patient tumors pre- and posttreatment with ALRN-6924. The colored bars indicate functional categories, as shown in the panel below. Genes labeled in black correspond to the set of IFN pathway genes which were induced in a p53-dependent manner upon treatment of cancer cell lines with different MDM2 inhibitors. Only those genes are shown which are included in PanCancer IO360 Gene Expression Panel. E, Model: top, at basal condition p53 binds to its response elements (RE) in ERVs and cooperates with DNMT1 and LSD1 to repress them. Bottom, upon pharmacologic p53 activation, p53 inhibits the expression of DNMT1 and LSD1, abrogating epigenetic silencing of ERVs. Furthermore, p53 binding to ERVs is increased along with p53 accumulation in cells. This is probably followed by the recruitment of transcriptional activators, replacing DNMT1 and LSD1. Together, these lead to the activation of expression of ERVs and generation of dsRNA. Active p53 downregulates RISC genes, contributing to dsRNA accumulation and dsRNA stress, induction of dsRNA sensors, and unleashing of viral mimicry response, thus potentiating anticancer immune response and synergy with immune checkpoint therapy.

We determined whether the set of viral mimicry response genes which we found to be induced by MDM2 inhibitors in cancer cell lines will be differentially expressed in patients upon treatment with the MDM2 inhibitor. We compared the expression of viral mimicry pathway-related genes in pre- and posttreatment tumor biopsy samples from the two patients with melanoma. As shown in Fig. 7D, several APP genes, IFN-related genes, dsRNA sensors, and immune checkpoint molecules were induced in patient tumors. More than a half of these genes we identified as the p53-dependent genes upregulated upon MDM2 inhibitors in human and mouse cancer cells of different origin.

Thus, in line with our preclinical studies, these clinical findings point to p53 activation as a powerful strategy to augment intratumoral IFN signaling and recruitment of tumor-suppressive immune cells to the tumor thereby boosting immune surveillance.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have demonstrated that pharmacologic activation of p53 induced the expression of ERVs and generation of dsRNA, which caused intracellular dsRNA stress leading to type I and type III IFN responses and induction of APP genes. We found that p53 activation promotes the recruitment of immune cells to tumors in mouse models in vivo and sensitizes refractory tumors to PD-1 blockade. Notably, the analysis of pre- and posttreatment tumor biopsy samples from patients with melanoma treated with the MDM2 inhibitor ALRN-6924 revealed the induction of viral mimicry response genes, as well as immune function signatures suggesting infiltration of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells. These results are very encouraging and suggest sensitization to immune therapy in patients, thereby underscoring the potential of combining MDM2 inhibitors with immune therapy.

Independent studies of patients with cancer who were treated with immunotherapy have provided fundamental insights into mechanisms promoting immune evasion, including loss of antigen presentation machinery or defects in IFN signaling (39). Unbiased CRISPR/Cas9 genetic screening on a genome scale identified genes involved in IFN signaling among the core CTL-evasion genes and pathways (40). Therefore, elucidation of the mechanisms and factors that can restore IFN signaling could lead to the design of combination therapeutic strategies for the treatment of low immunogenic cancers. Several studies demonstrated that ablation of repressive marks at ERVs, thus unleashing their expression, leads to the formation of dsRNA, which in turn triggers the IFN pathway thus boosting the response to immune checkpoint therapy (11, 12, 14, 15).

Importantly, a key to our findings is that pharmacologically activated p53 induces the transcription of a subset of ERVs in human and in mouse cells, which leads to the generation of dsRNA and dsRNA stress that triggers viral defense responses. We show that p53 accumulation upon MDM2 inhibition is associated with increased occupancy of p53 on ERV promoters. Moreover, p53-mediated inhibition of two major repressors of ERVs, histone demethylase LSD1 and DNA methyltransferase DNMT1, contributes to the derepression of ERVs. While DNMT1 has been shown to be repressed by p53 (24), inhibition of LSD1 has not been found before.

Our finding that activated p53 induces the expression of repetitive sequences is quite unexpected. Several previous studies have established that p53 antagonizes the expression of repetitive sequences, including ERVs. p53 response elements (RE) are found in ERV-derived LTRs, which accounted for 30% of p53-binding sites (6, 7). Interestingly, p53RE associated with transposons are high-affinity sites that are characterized by higher occupancy than nontransposon RE (41). Leonova and colleagues have shown that p53 together with DNMT1 is required for silencing repetitive elements. In the absence of wtp53, treatment of mouse cells with the DNMT1 inhibitor 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine resulted in increased transcription of repetitive elements. Produced dsRNA triggered the innate immune system in these cells to express IFN, which led to cell death (8). It has been found that p53 in flies and fish restrains the movement of repetitive mobile elements, along with DNA methylation, histone modifications, and the piRNA protein complexes (42). A recent study demonstrated that p53 binds to the internal promoter of human LINE1 retrotransposons and stimulates deposition of repressive histone marks for their transcriptional suppression (43). Furthermore, loss of p53 leads to derepression of LINE1 and chromosomal rearrangements linked to LINE1 elements (43). Together, these studies establish the suppression of repetitive elements as a conserved property of p53-mediated tumor suppression that safeguards human somatic cells against genomic instability (9).

In contrast to these prior, independent studies, our findings demonstrate the induction of ERV transcription upon pharmacologic activation of p53. To explain this paradox, we propose the following model (Fig. 7E). In unstressed cells p53 binds to its RE in ERVs and cooperates with DNMT1 and LSD1 to repress them. Therefore, p53 loss leads to partial derepression of ERVs, as shown in articles cited above. However, because p53 negatively regulates DNMT1 and LSD1, in the absence of p53 the expression of DNMT1 and LSD1 is increased, which partially compensates for the effect of p53 deficiency. On the contrary, upon pharmacologic p53 activation, DNMT1 and LSD1 expression is repressed, abrogating epigenetic silencing of ERVs. At the same time, p53 binding to ERV promoters is increased, along with overall p53 accumulation in cells. Increased p53 occupancy at ERV promoters is probably followed by the recruitment of transcriptional activators, replacing DNMT1 and LSD1. This leads to the activation of expression of ERVs, thus unleashing a viral mimicry response (Fig. 7E). It remains unclear why derepression occurs preferentially at ERVs, while other types of repetitive elements are mainly repressed. Furthermore, the relative contribution of different repetitive sequences to the shaping of the immune microenvironment remains to be determined.

Several studies have described the effect of pharmacologic activation of p53 on antitumor immunity, including IFN induction, polarization of macrophages, induction of PD-L1, and potentiation of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in cell culture and mouse tumor models (34, 44–47). Having identified the derepression of ERVs upon p53 activation as a mechanism that triggers IFN response, our study offers novel mechanistic insight into p53-mediated enhancement of antitumor immunity.

Much research effort has been dedicated to combining immune checkpoint inhibitors with standard-of-care chemotherapies. However, in clinical trials, both immunosuppressive and immunostimulating effects of chemotherapy in combination with checkpoint inhibitors have been observed (32). The absence of biomarkers allowing stratification of patients who will benefit from the combination treatment might account for failed clinical trials. Notably, Zitvogel and colleagues have found that anthracyclines stimulate the production of type I IFNs by cancer cells via activation of the endosomal pattern recognition receptor TLR3 (48). While the authors implicated TLR3 in the apical signal transduction of this pathway, the mechanism of TLR3/IFN induction by doxorubicin remained unclear. Our findings demonstrate that doxorubicin, via p53-mediated induction of ERVs, triggers the induction of dsRNA sensor TLR3 and the IFN response. On the basis of our findings taken together with previously published data, we speculate that wtp53 status might serve as one important biomarker that can predict the successful combination of anthracyclines with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Furthermore, it is possible that other DNA-damaging chemotherapeutics, known to activate p53, are likely to invoke the same or similar mechanisms of p53-induced innate and adaptive immune responses. It might also be beneficial to test the application of MDM2 inhibitors as an addition to standard therapy to sensitize tumors to immune checkpoint inhibitors.

In summary, our data in cancer cell lines, tumor-bearing mouse models, and patients with melanoma demonstrate that pharmacologic p53 reactivation triggers the ERV–dsRNA–IFN pathway within tumor cells thereby altering the tumor microenvironment toward a therapeutically responsive phenotype and evoking tumor immune surveillance. Restoring IFN signaling by pharmacologic reinstatement of p53 function has potential to release the “brake” that cancer uses to evade the immune system. The encouraging antitumor results shown reinforce the MDM2 inhibitor/immune checkpoint inhibitor combination results from Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Ascentage Pharma, who initiated human clinical trials to test these combinations in patients with cancer (clinicaltrials.gov). Our article provides a rational biological mechanism to explain the potentiation of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy by MDM2 inhibition to further justify pursuit of this combination as a therapeutic intervention for patients with cancer.

METHODS

Cell Culture

Human osteosarcoma SJSA-1 and U2OS cells lines were cultured in RPMI1640 medium (Hyclone) supplemented with 10% FBS (Hyclone), 100 U/mL of penicillin, and 100 mg/mL of streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich). Human melanoma A375, breast cancer MCF7, embryonic kidney 293T cells, and murine melanoma B16 were cultured in DMEM (Hyclone) supplemented with 10% FBS, and antibiotics. All cell lines were incubated in 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C and tested negative for Mycoplasma before assay.

Compounds

Types and sources of compounds and their treatment conditions used for in vitro experiments are described in the Supplementary Methods.

Accession Numbers

RNA-seq profiles were downloaded from the publicly available data with accession number GSE8622. p53 ChIP-seq data from nutlin-treated cells were obtained from GSE86164.

RNA extraction, reverse transcription quantitative PCR, and immunoblot were performed as described previously (49). Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table S3. Antibodies are listed in Supplementary Methods.

dsRNA Analysis by J2 Dot Blot and dsRNA analysis by immunofluorescent staining were performed as described previously (15, 22). For details, see Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References.

ELISA Detection of IFNα

After 7041 treatment, the culture media were replaced with serum-free media for 24 hours. The supernatant was collected by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 5 minutes subjected to a Human IFNα (pan specific) ELISAPRO kit (MABTECH) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The data were analyzed using elisaanalysis.com.

Flow Cytometry

For MHC class I detection and OVA-peptide detection, 106 cancer cells per condition were stained with the appropriate antibodies diluted in PBS plus 2% FBS (Hyclone) for 30 minutes on ice. Matched isotype control was used to subtract the noise. To omit dead cells during analysis, cells were stained with 1 μg/mL propidium iodide (Thermo Fisher Scientific, catalog no. P3566) before assay. Antibodies information is listed in Supplementary Table S3.

The intracellular dsRNA detection using J2 antibody was performed as described above, except cells were permeabilized and blocked with 0.1% Triton X-100 in FACS buffer for 15 minutes at room temperature.

For IFN reporter assay, the ISRE-mCherry–transduced cells were treated with compounds for 24 hours, trypsinized, washed, and saturated in ice-cold PBS.

Immuno-profiling of splenocytes was performed as described previously (50). For details, see Supplementary Methods. FACS analyses were performed on FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences), LSR II (BD Biosciences) or LSRFortessa X-20 (BD Biosciences) and the data were analyzed by CellQuest Pro and FlowJo (version 10.5.3 Tree Star Inc.).

Animal Experiments

Animal experiments were approved by the regional ethics committee for animal research (N391/11 and N26/11), appointed and under the control of the Swedish Board of Agriculture and the Swedish Court. The animal experiments were in accordance with national regulations (SFS 1988:534, SFS 1988:539 and SFS 1988:541).

For the B16 melanoma mouse model, 6-week-old female C57BL/6 mice were injected subcutaneously with 1 × 106 B16 cells. For Colon26 mice model, 8- to 12-week-old BALB/c mice were implanted with 1 × 106 Colon26 cells subcutaneously. When the tumors reached 80–120 mm3, 30 mg/kg of ATSP-7041 for B16 model or 20 mg/kg ALRN-6924 for Colon26 model were administered intravenously twice weekly for two weeks (days 1, 4, 8, 11). For antibody treatment, mice were given 10 mg/kg of anti–PD-1 or isotype control (BioXCell, Nordic Biosite) antibody via intraperitoneal injection at day 5, 9, and 12. Tumor volume was measured by caliper three times per week, and the volume was calculated based on the formula (in ml): L/10*W/10*W/10*0.44 (L, length; W, width of tumor). Mice were sacrificed when tumors reached 2 cm3 or upon bleeding. A satellite group in n = 6 mice/group was sacrificed for analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells at day 14. Twenty-four hours after the final dose each satellite animal was euthanized, and the tumor was harvested and processed for flow cytometry.

Patient Data

Patients 18 years or older with advanced solid tumors or lymphomas were recruited to participate in a phase I, open-label, multicenter, dose-escalation trial registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02264613) and was conducted with adherence to all local and national guidelines and in compliance with good clinical practice and with approval of institutional review boards at each participating clinical site. Tumor TP53-wt status was conducted using next-generation sequencing of TP53, and nucleic acid extract from pre- and posttreatment biopsies was analyzed using the NanoString PanCancer IO360 and Immune Profiling platform (NanoString Technologies Inc.; www.nanostring.com). All samples were obtained from patients who provided written informed consent.

CyTOF

The mass cytometry data were obtained and analyzed as previously described (51). For details, see Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References.

Authors' Disclosures

V. Guerlavais reports other support from Aileron Therapeutics outside the submitted work. L. Carvajal was an employee of Aileron Therapeutics. M. Aivado reports other support from Aileron Therapeutics during the conduct of the study; in addition, M. Aivado has a patent for Peptidomimetic Macrocycles and uses thereof pending. D. Annis reports personal fees from Aileron Therapeutics, Inc during the conduct of the study. J. Johnsen reports grants from The Swedish Cancer Foundation, grants from The Cancer Research Foundations of Radiumhemmet, and grants from Märta and Gunnar V Philipson Foundation during the conduct of the study; grants from The Swedish Childhood Cancer Foundation outside the submitted work. G. Selivanova is a co-founder of Aprea Therapeutics AB, developing mutant p53-reactivating compounds. No disclosures were reported by the other authors.

Supplementary Material

P53 CHIP-SEQ

Raw data for FACs profiling of immune cells on CT26

Primers, siRNAs and CRISPR guide RNAs

All Supplementary Figures

Supplementary Methods

References for supplementary methods file

Acknowledgments

We are greatly indebted to all our colleagues who provided reagents and cell lines to us and CyTOF facility at SciLifeLab for their help.

This study was supported by the Swedish Cancer Society (20 1127 PjF 01 H, to G. Selivanova), the Swedish Research Council (2019-01725, to G. Selivanova), and the Karolinska Institutet Research foundation (to G. Selivanova).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of publication fees. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Cancer Discovery Online (http://cancerdiscovery.aacrjournals.org/).

Authors' Contributions

X. Zhou: Conceptualization, data curation, software, formal analysis, validation, investigation, visualization, methodology, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing. M. Singh: Conceptualization, data curation, software, formal analysis, validation, investigation, visualization, methodology, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing. G. Sanz Santos: Data curation, formal analysis, visualization, writing–original draft. V. Guerlavais: Data curation, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, methodology. L. Carvajal: Data curation, investigation. M. Aivado: Data curation, investigation. Y. Zhan: Data curation, investigation. M.M. Oliveira: Data curation, investigation, methodology. L.S. Westerberg: Resources, data curation, supervision, methodology, writing–review and editing. D. Annis: Data curation, investigation. J. Johnsen: Resources, data curation, validation, methodology, writing–review and editing. G. Selivanova: Conceptualization, resources, software, supervision, funding acquisition, validation, investigation, visualization, writing–original draft, project administration, writing–review and editing.

References

- 1. Martins CP, Brown-Swigart L, Evan GI. Modeling the therapeutic efficacy of p53 restoration in tumors. Cell 2006;127:1323–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ventura A, Kirsch DG, McLaughlin ME, Tuveson DA, Grimm J, Lintault Let al. Restoration of p53 function leads to tumour regression in vivo. Nature 2007;445:661–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Xue W, Zender L, Miething C, Dickins RA, Hernando E, Krizhanovsky Vet al. Senescence and tumour clearance is triggered by p53 restoration in murine liver carcinomas. Nature 2007;445:656–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sanz G, Singh M, Peuget S, Selivanova G. Inhibition of p53 inhibitors: progress, challenges and perspectives. J Mol Cell Biol 2019;11:586–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chang YS, Graves B, Guerlavais V, Tovar C, Packman K, To KHet al. Stapled alpha-helical peptide drug development: a potent dual inhibitor of MDM2 and MDMX for p53-dependent cancer therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013;110:E3445–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Harris CR, Dewan A, Zupnick A, Normart R, Gabriel A, Prives Cet al. p53 responsive elements in human retrotransposons. Oncogene 2009;28:3857–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang T, Zeng J, Lowe CB, Sellers RG, Salama SR, Yang Met al. Species-specific endogenous retroviruses shape the transcriptional network of the human tumor suppressor protein p53. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007;104:18613–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Leonova KI, Brodsky L, Lipchick B, Pal M, Novototskaya L, Chenchik AAet al. p53 cooperates with DNA methylation and a suicidal interferon response to maintain epigenetic silencing of repeats and noncoding RNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013;110:E89–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Levine AJ, Ting DT, Greenbaum BD. P53 and the defenses against genome instability caused by transposons and repetitive elements. Bioessays 2016;38:508–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Groh S, Schotta G. Silencing of endogenous retroviruses by heterochromatin. Cell Mol Life Sci 2017;74:2055–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chiappinelli KB, Strissel PL, Desrichard A, Li H, Henke C, Akman Bet al. Inhibiting DNA methylation causes an interferon response in cancer via dsRNA including endogenous retroviruses. Cell 2015;162:974–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Roulois D, Loo Yau H, Singhania R, Wang Y, Danesh A, Shen SYet al. DNA-demethylating agents target colorectal cancer cells by inducing viral mimicry by endogenous transcripts. Cell 2015;162:961–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Parker BS, Rautela J, Hertzog PJ. Antitumour actions of interferons: implications for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2016;16:131–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Goel S, DeCristo MJ, Watt AC, BrinJones H, Sceneay J, Li BBet al. CDK4/6 inhibition triggers anti-tumour immunity. Nature 2017;548:471–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sheng W, LaFleur MW, Nguyen TH, Chen S, Chakravarthy A, Conway JRet al. LSD1 ablation stimulates anti-tumor immunity and enables checkpoint blockade. Cell 2018;174:549–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Weber J. Immune checkpoint proteins: a new therapeutic paradigm for cancer–preclinical background: CTLA-4 and PD-1 blockade. Semin Oncol 2010;37:430–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Perier-Muzet M, Gatt E, Peron J, Falandry C, Amini-Adle M, Thomas Let al. Association of immunotherapy with overall survival in elderly patients with melanoma. JAMA Dermatol 2018;154:82–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sharma P, Hu-Lieskovan S, Wargo JA, Ribas A. Primary, adaptive, and acquired resistance to cancer immunotherapy. Cell 2017;168:707–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kastenhuber ER, Lowe SW. Putting p53 in context. Cell 2017;170:1062–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Munoz-Fontela C, Mandinova A, Aaronson SA, Lee SW. Emerging roles of p53 and other tumour-suppressor genes in immune regulation. Nat Rev Immunol 2016;16:741–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Andrysik Z, Galbraith MD, Guarnieri AL, Zaccara S, Sullivan KD, Pandey Aet al. Identification of a core TP53 transcriptional program with highly distributed tumor suppressive activity. Genome Res 2017;27:1645–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Leonova K, Safina A, Nesher E, Sandlesh P, Pratt R, Burkhart Cet al. TRAIN (Transcription of Repeats Activates INterferon) in response to chromatin destabilization induced by small molecules in mammalian cells. eLife 2018;7:e30842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fischer M, Quaas M, Steiner L, Engeland K. The p53-p21-DREAM-CDE/CHR pathway regulates G2/M cell cycle genes. Nucleic Acids Res 2016;44:164–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lin RK, Wu CY, Chang JW, Juan LJ, Hsu HS, Chen CYet al. Dysregulation of p53/Sp1 control leads to DNA methyltransferase-1 overexpression in lung cancer. Cancer Res 2010;70:5807–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li H, Lakshmikanth T, Garofalo C, Enge M, Spinnler C, Anichini Aet al. Pharmacological activation of p53 triggers anticancer innate immune response through induction of ULBP2. Cell Cycle 2011;10:3346–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tan HH, Porter AG. p21(WAF1) negatively regulates DNMT1 expression in mammalian cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2009;382:171–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ho JS, Ma W, Mao DY, Benchimol S. p53-Dependent transcriptional repression of c-myc is required for G1 cell cycle arrest. Mol Cell Biol 2005;25:7423–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chaudhary R, Lal A. Long noncoding RNAs in the p53 network. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 2017;8: 10.1002/wrna.1410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Qi HH, Ongusaha PP, Myllyharju J, Cheng D, Pakkanen O, Shi Yet al. Prolyl 4-hydroxylation regulates Argonaute 2 stability. Nature 2008;455:421–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kassiotis G, Stoye JP. Immune responses to endogenous retroelements: taking the bad with the good. Nat Rev Immunol 2016;16:207–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Munoz-Fontela C, Macip S, Martinez-Sobrido L, Brown L, Ashour J, Garcia-Sastre Aet al. Transcriptional role of p53 in interferon-mediated antiviral immunity. J Exp Med 2008;205:1929–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wu J, Waxman DJ. Immunogenic chemotherapy: dose and schedule dependence and combination with immunotherapy. Cancer Lett 2018;419:210–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhou F. Molecular mechanisms of IFN-gamma to up-regulate MHC class I antigen processing and presentation. Int Rev Immunol 2009;28:239–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fang DD, Tang Q, Kong Y, Wang Q, Gu J, Fang Xet al. MDM2 inhibitor APG-115 synergizes with PD-1 blockade through enhancing antitumor immunity in the tumor microenvironment. J Immunother Cancer 2019;7:327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cha JH, Chan LC, Li CW, Hsu JL, Hung MC. Mechanisms controlling PD-L1 expression in cancer. Mol Cell 2019;76:359–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kleffel S, Posch C, Barthel SR, Mueller H, Schlapbach C, Guenova Eet al. Melanoma cell-intrinsic PD-1 receptor functions promote tumor growth. Cell 2015;162:1242–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Meric-Bernstam F, Saleh MN, Infante JR, Goel S, Falchook GS, Shapiro Get al. Phase I trial of a novel stapled peptide ALRN-6924 disrupting MDMX- and MDM2-mediated inhibition of WT p53 in patients with solid tumors and lymphomas. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:2505. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ayers M, Lunceford J, Nebozhyn M, Murphy E, Loboda A, Kaufman DRet al. IFN-gamma-related mRNA profile predicts clinical response to PD-1 blockade. J Clin Invest 2017;127:2930–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rooney MS, Shukla SA, Wu CJ, Getz G, Hacohen N. Molecular and genetic properties of tumors associated with local immune cytolytic activity. Cell 2015;160:48–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lawson KA, Sousa CM, Zhang X, Kim E, Akthar R, Caumanns JJet al. Functional genomic landscape of cancer-intrinsic evasion of killing by T cells. Nature 2020;586:120–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Su D, Wang X, Campbell MR, Song L, Safi A, Crawford GEet al. Interactions of chromatin context, binding site sequence content, and sequence evolution in stress-induced p53 occupancy and transactivation. PLoS Genet 2015;11:e1004885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wylie A, Jones AE, D'Brot A, Lu WJ, Kurtz P, Moran JVet al. p53 genes function to restrain mobile elements. Genes Dev 2016;30:64–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tiwari B, Jones AE, Caillet CJ, Das S, Royer SK, Abrams JM. p53 directly represses human LINE1 transposons. Genes Dev 2020;34:1439–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Li L, Ng DS, Mah WC, Almeida FF, Rahmat SA, Rao VKet al. A unique role for p53 in the regulation of M2 macrophage polarization. Cell Death Differ 2015;22:1081–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Li R, Zatloukalova P, Muller P, Gil-Mir M, Kote S, Wilkinson Set al. The MDM2 ligand Nutlin-3 differentially alters expression of the immune blockade receptors PD-L1 and CD276. Cell Mol Biol Lett 2020;25:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Guo G, Yu M, Xiao W, Celis E, Cui Y. Local activation of p53 in the tumor microenvironment overcomes immune suppression and enhances antitumor immunity. Cancer Res 2017;77:2292–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sahin I, Zhang S, Navaraj A, Zhou L, Dizon D, Safran Het al. AMG-232 sensitizes high MDM2-expressing tumor cells to T-cell-mediated killing. Cell Death Discov 2020;6:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sistigu A, Yamazaki T, Vacchelli E, Chaba K, Enot DP, Adam Jet al. Cancer cell-autonomous contribution of type I interferon signaling to the efficacy of chemotherapy. Nat Med 2014;20:1301–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Peuget S, Zhu J, Sanz G, Singh M, Gaetani M, Chen Xet al. Thermal proteome profiling identifies oxidative-dependent inhibition of the transcription of major oncogenes as a new therapeutic mechanism for select anticancer compounds. Cancer Res 2020;80:1538–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kritikou JS, Oliveira MM, Record J, Saeed MB, Nigam SM, He Met al. Constitutive activation of WASp leads to abnormal cytotoxic cells with increased granzyme B and degranulation response to target cells. JCI Insight 2021;6:e140273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Nowicka M, Krieg C, Crowell HL, Weber LM, Hartmann FJ, Guglietta Set al. CyTOF workflow: differential discovery in high-throughput high-dimensional cytometry datasets. F1000Res 2017;6:748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

P53 CHIP-SEQ

Raw data for FACs profiling of immune cells on CT26

Primers, siRNAs and CRISPR guide RNAs

All Supplementary Figures

Supplementary Methods

References for supplementary methods file