Abstract

A DNA fragment carrying the genes coding for EcoO109I endonuclease and EcoO109I methylase, which recognize the nucleotide sequence 5′-(A/G)GGNCC(C/T)-3′, was cloned from the chromosomal DNA of Escherichia coli H709c. The EcoO109I restriction-modification (R-M) system was found to be inserted between the int and psu genes from satellite bacteriophage P4, which were lysogenized in the chromosome at the P4 phage attachment site of the corresponding leuX gene observed in E. coli K-12 chromosomal DNA. The sid gene of the prophage was inactivated by insertion of one copy of IS21. These findings may shed light on the horizontal transfer and stable maintenance of the R-M system.

Escherichia coli H709c has been widely used as an antigenic tester strain of the E. coli O109 group, and the serotype formula of this strain was established as O109:K(−):H19 by Ørskov et al. (23). A type II restriction endonuclease, R.EcoO109I, which recognizes and cleaves the nucleotide sequence of 5′-(A/G)G↓GNCC(C/T)-3′, has been isolated from E. coli H709c (21). It has been reported that R.EcoO109I cleavage is inhibited by the modification of the outer cytosine in the recognition sequence (29). However, neither the position nor the products of methylation by the cognate methyltransferase, M.EcoO109I, have been determined yet.

To date, about 150 type II restriction-modification (R-M) genes have been cloned and their nucleotide sequences have been analyzed (27). The genes coding for endonuclease and methyltransferase are closely linked on either chromosomal DNA or plasmid DNA. Of the 167 type II R-M enzymes isolated from E. coli, 11 genes have been cloned and their nucleotide sequences have been analyzed. The EcoRI (22), EcoRV (3), EcoRII (16), and Eco29kI (40) systems are encoded by plasmid DNA, whereas the EcoHK31I (17) system is encoded by chromosomal DNA. The characterization of type II R-M systems has shown that some systems contain other components in addition to the requisite endonuclease and methyltransferase. One of these is the C element, which is known to activate R expression in the BamHI and PvuII R-M systems (12, 33). Genes encoding proteins involved in DNA mobility, such as transposases, integrases, and invertases, are sometimes found in the vicinity of R-M systems located on chromosomal DNA (1, 5, 13, 17, 31, 35). These proteins might facilitate the transfer of R-M genes among different bacterial strains.

In this study, we report the cloning and characterization of the EcoO109I R-M system and the location of the system on the chromosome. The nucleotide sequence adjacent to the R-M system has led to interesting speculation about the evolutionary history of EcoO109I.

Purification of R.EcoO109I and M.EcoO109I.

R.EcoO109I and M.EcoO109I were partially purified from the cell extracts by combined chromatography on DEAE-Sephacel, phosphocellulose, hydroxylapatite, and heparin-Sepharose. When the peak fractions were electrophoresed on a sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel, R.EcoO109I and M.EcoO109I produced major bands of 32.5 and 45 kDa, respectively. The corresponding bands were blotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (20) and then subjected to N-terminal amino acid sequence analysis. The first 20 amino acids of R.EcoO109I and M.EcoO109I obtained on Edman degradation were Met-Asn-Lys-Gln-Glu-Val-Ile-Leu-Lys-Val-Gln-Glu-Xxx-Ala-Ala- Trp-Trp-Ile-Leu-Glu and Ser-Ser-Lys-Lys-Phe-Ile-Ser-Leu- Phe-Ser-Gly-Ala-Met-Gly-Leu-Xxx-Leu-Gly-Leu-Gln (Xxx, not identified), respectively.

Isolation of EcoO109I R-M genes.

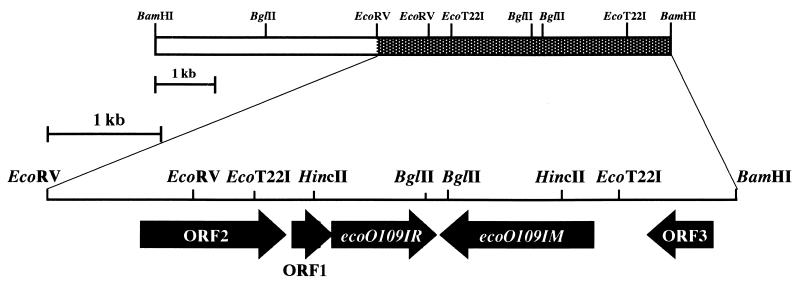

To isolate the two genes, oligonucleotide N1 (Table 1) was synthesized from the N-terminal amino acid sequence of R.EcoO109I and used as a probe for Southern hybridization with E. coli H709c chromosomal DNA digested with various restriction endonucleases. The 4.8-kb BglII fragment was cloned into the BamHI site of the pUC118 vector to obtain pUC-B1. The purified plasmid DNA from the clone was digested with R.EcoO109I, and the plating efficiency of λ virulent phage for the cells carrying pUC-B1 was the same as that for control cells carrying no plasmid. These results suggested that a partial, i.e., not the complete, EcoO109I R-M gene was located on the 4.8-kb BglII fragment. In order to find longer DNA fragments carrying genes encoding complete EcoO109I R-M enzymes within the E. coli H709c chromosomal DNA, the 9-kb BamHI fragment was cloned into the BamHI site of the λEMBL3 vector to obtain EMBL3-25. DNA was purified from the phage, and the 5.8-kb EcoRV-BamHI fragment was analyzed in detail (Fig. 1). The 3.1-kb EcoT22I fragment was inserted into the PstI site of pKF3 and the resulting recombinant plasmid, pKF3-1, was transferred to E. coli TH2. R.EcoO109I activity in the cell extract was assayed at 37°C by adding 2 μl of enzyme solution to 15 μl of reaction mixture (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.5 μg of T4 cytosine-containing DNA [dC DNA]). M.EcoO109I activity was assayed as the susceptibility of pKF3-1 to R.EcoO109I. The colonies carrying the plasmid expressed both endonuclease and methyltransferase activities. These results indicated that the 3.1-kb region is essential for encoding both the restriction endonuclease and the methyltransferase.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, phages, and oligonucleotides

| Strain, plasmid, phage, or oligonucleotide | Relevant characteristic(s) and description | Reference(s) or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| H709c | O109:K(−):H19 | 21, 23 |

| HB101 | supE44 hsdS20(rB− mB−) recA13 ara-14 proA2 lacY1 galK2 rpsL20 xyl-5 mtl-1 leuB6 thi-1 | 4 |

| JM109 | recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi hsdR17 supE44 relA1 Δ(lac-proAB)/F′ [traD36 proAB+lacIqlacZΔM15] | 39 |

| LE392 | F−hsdR514(rK− mK−) supE44 supF58 lacY1 galK2 galT22 metB1 trpR55 λ− | 28 |

| TH2 | supE44 hsdS20 (rB− mB−) recA13 ara-14 proA2 lacY1 galK2 rpsL20 xyl-5 mtl-1 thi trpR624 | 34 |

| W3110 | K-12 F− λ− | Lab collection |

| XL-1 Blue MRF′ | Δ(mcrA)183 Δ(mcrCB-hsdSMR-mrr)173 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi1 supE44 relA1 lac/F′ [proAB+ lacIqlacZΔM15::Tn10(Tetr)] | Stratagene |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC118 | Cloning vector | 39 |

| pKF3-1 | Cloning vector | 10 |

| pGEM-T | Cloning vector | Promega |

| pUC-B1 | 4.8-kb BglII insert from E. coli H709c chromosomal DNA cloned in BamHI of pUC118 | This study |

| pKF3-1 | 3.1-kb EcoT22I insert with R.EcoO109I and M.EcoO109I genes from EMBL3-25 cloned in PstI of pKF3 | This study |

| Phages | ||

| λgtλC | Virulent phage | 14 |

| λEMBL3 | Cloning vector | Clontech |

| EMBL3-25 | 9.0-kb BamHI insert with R.EcoO109I and M.EcoO109I genes in BamHI site of λEMBL3 | This study |

| Oligonucleotides with special features | ||

| N1 | 5′-CA(A/G)GA(A/G)TG(C/T)GCIGCITGGTGAAT-3′ | This study |

| R1 | 5′-CTTTTATATCTGCTTCTTTTACAGC-3′ | This study |

| R2 | 5′-TATATGCTGGTAAAGAATTTTGGTC-3′ | This study |

| δ-Ca | 5′-CAGCCCTCATTCCAGACGCAGCGAATATGATTGTG-3′ | This study |

| δ-Na | 5′-TGATTTACTGTCCGTCGTGTGGACATGTTGCTCAC-3′ | This study |

| Att | 5′-CGAAGGCCGGACTCAAACATCAAAATAAGTTAATG-3′ | This study |

| sid-Ca | 5′-GTGTGAGCAACATGTCCACACGACGGACAG-3′ | This study |

| sid-N topa | 5′-CTGACCACACTATCCCTGAATATCTGCAAC-3′ | This study |

| sid-N bottoma | 5′-GTTGCAGATATTCAGGGATAGTGTGGTCAG-3′ | This study |

| mcrC-Ca | 5′-TTATTTGAGATATTCATCGAAAATGTCGAG-3′ | This study |

| mcrC-Na | 5′-GTGGAACAGCCCGTGATACCTGTCCGTAAT-3′ | This study |

| mcrB-Ca | 5′-CTATGAGTCCCCTAATAATTTGTTGGTCCA-3′ | This study |

| mcrB-Na | 5′-ATGAGGAAGGCATATCTTATGGAATCTATT-3′ | This study |

| hsdS-Ca | 5′-TCAGGATTTTTTACGTGAGGCTTTTTTACC-3′ | This study |

| hsdR-Na | 5′-ATGTTATGGGCCTTAAATATTTGGACAGGC-3′ | This study |

| mrr-Ca | 5′-TCACTCAAAATAGTCCATATCCAGTTTCGG-3′ | This study |

| mrr-Na | 5′-ATGACGGTTCCTACCTATGACAAATTTATT-3′ | This study |

| mcrA-Ca | 5′-TTATTTCTGTAATCGGTTTATATTAACGTA-3′ | This study |

| mcrA-Na | 5′-ATGCATGTTTTTGATAATAATGGAATTGAA-3′ | This study |

Oligonucleotides were synthesized based on the nucleotide sequence encoding N-terminal (N) and C-terminal (C) regions of each protein.

FIG. 1.

Restriction map of the 9-kb BamHI fragment. The positions and orientation of the R.EcoO109I (ecoO109IR) and M.EcoO109I (ecoO109IM) genes, as well as those of ORF1, ORF2, and ORF3, are indicated by arrows.

Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences.

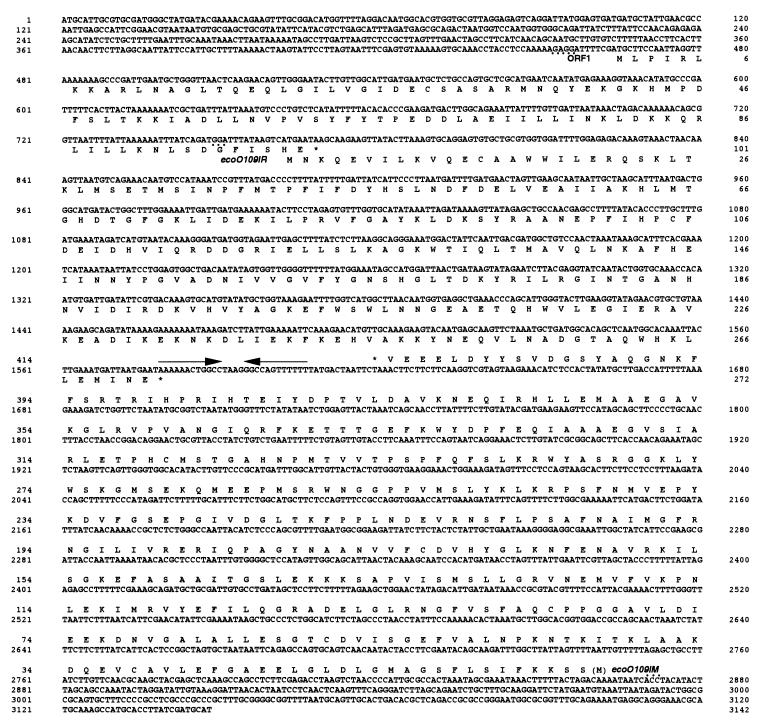

The DNA sequence of the 3.1-kb EcoT22I fragment that covers the entire EcoO109I R-M gene is shown in Fig. 2. The two open reading frames (ORFs) were aligned tail to tail, and a 38-bp spacer region was found between them. A putative palindromic sequence, which is found in the StsI R-M system (15), was seen within the spacer region; this could be the transcriptional termination site for both genes. In the ORF assigned to the endonuclease gene, an ATG codon appeared at nucleotide position 762 and a termination codon at nucleotide position 1578. In addition, an appropriate ribosome-binding sequence, GGA, was present 11 bp upstream of the ATG codon. The ORF consisted of 816 bp and encoded a 272-amino-acid-residue polypeptide. The predicted mass, 31,435 Da, was close enough to the value estimated on SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. R.EcoO109I exhibits identity with R.SinI (13) and R.Eco47I (31), which recognize G ↓ G(A/T)CC, and R.Sau96I (32) and R.Eco47II (31), which recognize G ↓ GNCC.

FIG. 2.

Nucleotide sequence of the 3,142-bp EcoT22I fragment. The amino acid sequences assigned to ecoO109IR and ORF1 are given below the nucleotide sequence, and the sequence assigned to ecoO109IM is given above the nucleotide sequence. The nucleotide sequence is numbered from the leftmost end, and the amino acid sequences of ecoO109IR and ecoO109IM are numbered from the initiation codon of each gene. The potential ribosome-binding sequences are dotted. A pair of arrows indicates palindromic sequences characteristic of the termination signal.

In the ORF assigned to the methylase gene, a TTG codon appeared at nucleotide position 2863, an ATG codon appeared at nucleotide position 2823, and a termination codon appeared at nucleotide position 1620. The ORF consisted of 1,242 bp and encoded a 414-amino-acid-residue polypeptide. The predicted mass, 45,701 Da, was close enough to the value estimated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. An appropriate ribosome-binding sequence, AGG, was present 8 bp upstream of the TTG codon. M.EcoO109I exhibits identity with M.SinI (13), M.HgiBI (6), M.HgiCII (7), and M.HgiEI (8), which recognize GG(A/T)CC, and M.Sau96I (32), M.Eco47II (31), and M.PspI (26), which recognize GGNCC. All these methylases catalyze the formation of 5-methylcytosine at the inner cytosine (24).

Sequences flanking the R-M system.

Two additional ORFs (ORF1 and ORF2) and one ORF (ORF3) were discovered upstream of the R.EcoO109I and the M.EcoO109I genes, respectively. ORF1 (303 bp) was discovered upstream of the R.EcoO109I gene and partially overlaps the gene. A molecular mass of 11,455 Da is in good agreement with the predicted sizes of other C proteins, which associate with several type II R-M systems and regulate the expression of R-M genes (1, 37). ORF1 appears to be distantly related to known C proteins but shows homology to the DNA-binding domains of various regulatory proteins (18, 36, 38). The role of ORF1 is under investigation.

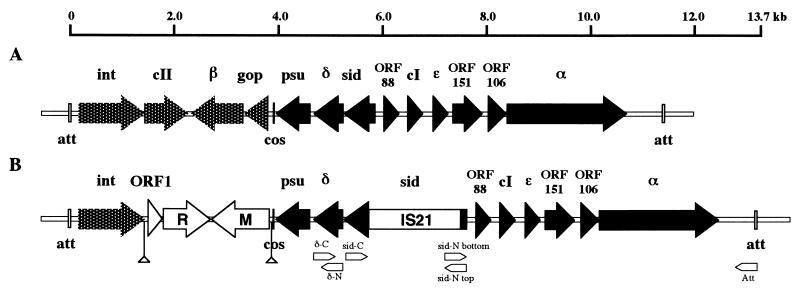

One ORF (ORF2; 1,284 bp), which showed significant homology to the integrase from the P4 phage (9), was identified upstream of ORF1. Furthermore, BLAST searches of the GenBank database revealed that a DNA sequence similar to that of the P4 phage attachment site followed by the E. coli K-12 MG1655 leuX gene (2) was found upstream of the int gene. The 190-amino-acid polypeptide (ORF3) encoded upstream of the M.EcoO109I gene also exhibited similarity with the psu gene product from the P4 phage. The DNA upstream of M.EcoO109I also contains sequences that exhibit identity with the cos sequence and δ genes from the P4 phage. From these results, we assumed that the DNA of the hybrid P4 phage, in which the cII, β, and gop genes were replaced by R-M genes (including ORF1), was inserted into E. coli H709c chromosomal DNA through site-directed recombination catalyzed by P4 integrase.

In order to confirm that the complete P4 genes, except for the cII, β, and gop genes, were inserted into the E. coli H709c chromosome, we synthesized several oligonucleotides based on the DNA sequence of P4 phage DNA and used them for PCR (Table 1). PCR was carried out with ExTaq DNA polymerase and an LA-PCR kit (Takara Shuzo Co. Ltd., Kyoto, Japan) as recommended by the manufacturer. The lengths of the fragments amplified from E. coli H709c DNA with the δ-N, δ-C, sid-N bottom, and Att oligonucleotides were the same as expected from the nucleotide sequence. The restriction profiles of these fragments were the same as expected. However, the fragments amplified with the δ-C and Att oligonucleotides were 2 kb longer than expected. These results suggested the possibility of rearrangement or insertion of a new sequence into the sid gene. The nucleotide sequence of the 3-kb DNA fragment amplified with the sid-C and sid N-top oligonucleotides was analyzed, and it was shown that one copy of IS21 (25) was inserted between nucleotides 312 and 313 in the top strand and between nucleotides 308 and 309 in the bottom strand of the sid gene, which generated a frameshift mutation of the sid protein. The results are summarized in Fig. 3.

FIG. 3.

Schematic diagram of the EcoO109I R-M genes on the E. coli H709c chromosome. (A) Gene order of the P4 phage integrated into the E. coli chromosome. (B) Gene order of the E. coli H709c chromosome adjacent to EcoO109I R-M genes. The genes, their directions of transcription, and cos and phage attachment sites (att) are shown. Genes that are necessary and unnecessary for lytic growth of the P4 phage are shown by black and dotted arrows, respectively. The positions where the R-M system is integrated into P4 are indicated by open triangles. R and M represent ecoO109IR and ecoO109IM, respectively. The locations of the PCR primers used for amplification of the genes are also indicated.

Absence of type I R-M genes and a methylation-specific restriction system in E. coli H709c.

E. coli has been shown to contain type I R-M systems, such as EcoK, EcoB, and EcoIC, as well as restriction systems requiring modification, such as Mcr and Mrr. In order to determine whether or not E. coli H709c possesses one of those genes for type I R-M systems and systems requiring modification, in addition to the type II EcoO109I R-M system, we amplified these genes by PCR. Primers based on the nucleotide sequence of E. coli K-12 MG1655 were designed to amplify these genes (Table 1). DNA fragments of the expected sizes were amplified from E. coli W3110 DNA but not from E. coli H709c or E. coli XL-1 Blue MRF′ DNA. These results suggested that E. coli H709c did not contain the EcoK, mcrABC, and mrr genes, which are present in E. coli K-12 derivatives.

There have been several reports of the close association between enzymes involved in DNA mobility and R-M systems. A partial P4 phage int gene occurs next to the R.SinI (13), M.EcoHK31I, and M.EaeI genes (17); a partial integrase gene of retronphage φR73 also occurs next to the R.EaeI gene (11, 17); and a gene for the Int family of recombinases occurs 3′ to the M.AccI gene (5). A gene for a DNA invertase-like enzyme is found near the M.PaeR7I (35) gene, and the transposon resolvase gene is located upstream of the R.BglII gene (1). A putative transposase-encoding gene is found in the intergenic area between the R.Eco47I and M.Eco47II genes (31). These enzymes are supposed to facilitate the transfer of the R-M systems among bacterial species.

We found that complete P4 phage genes, other than the cII, β, and gop genes, were lined up in a sequential order adjacent to the EcoO109I R-M system. Furthermore, a DNA sequence similar to that of the P4 phage attachment site, followed by E. coli K-12 MG1655 chromosomal DNA, was found upstream of the int gene. Comparison of the G+C contents of the sequenced regions of the EcoO109I R-M system, including ORF1 and the surrounding system, revealed an interesting feature: although the overall G+C content of P4 phage DNA was 49%, the genes in the EcoO109I R-M system had an average G+C content of 36%. This indicates that the P4 phage was lysogenized in the E. coli H709c chromosome at the P4 attachment site observed in E. coli K-12, in which genes nonessential for lytic growth, i.e., the cII, β, and gop genes, were replaced by EcoO109I R-M genes, including ORF1.

P4 can complete its life cycle only if it infects a cell that already has a helper phage, such as P2, within it or if a helper phage is supplied later. This means that P4 acts as a satellite phage or a parasite. We have found that one copy of IS21 was inserted in the sid gene, which generates a frameshift mutation of the sid protein. The sid gene product is supposed to be responsible for determining the precise size and symmetry of the structure into which the helper P2 gene products will assemble. Inactivation of the P4 sid gene does not necessarily prevent the formation of plaques, and the mutant produces P4 PFU with large P2-sized capsids which contain two or three copies of the mutant P4 genome (30).

P4 can inject its own DNA into E. coli and other gram-negative bacteria, such as Salmonella and Klebsiella (19). When P4 infects a sensitive E. coli host harboring the genome of helper phage P2, it may enter either the lysogenic or lytic pathway, being dependent on all the morphopoietic and lytic functions encoded by the helper to accomplish the latter mode of replication. In the absence of the helper phage, infection of E. coli by P4 may lead to either an immune-integrated condition, analogous to the lysogenic state, or the establishment of the multicopy plasmid mode of maintenance. This property, as well as P4’s genetic organization, suggests that P4 may be considered an episomal element that evolved the ability to exploit a helper bacteriophage for horizontal propagation through a novel specialized transduction mechanism (19). These data are consistent with the following hypothesis for the transfer of the EcoO109I R-M system to the chromosome DNA. First, a hybrid P4, in which the cII, β, and gop genes were replaced by EcoO109I R-M genes, was produced through bacterial recombination. Second, the bacteria carrying the hybrid P4 were infected by a helper phage, such as P2, and thus the P4 phage particles were released. Third, E. coli H709c was infected by the hybrid P4 phage, and the P4 DNA was integrated into the chromosome. Finally, the sid gene was inactivated by the insertion of IS21, and the prophage carrying the EcoO109I R-M system was maintained stably on the chromosome. It is conceivable that migration of the R.EcoO109I gene alone is not unfavorable for the P4 phage because of the lack of a target site of R.EcoO109I in its DNA (9) but is lethal for the host cell. It is quite interesting that the int genes found in four of seven R-M systems were similar to those of P4 and related φR73 phages. Extensive analysis of the nucleotide sequences adjacent to other R-M systems will provide clues to the evolution and migration of the R-M systems in bacteria.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The GenBank accession number for the DNA sequence of the gene encoding the EcoO109I R-M system is AF157599.

Acknowledgments

E. coli H709c was obtained from M. Miyahara (Institute of Public Health, Tokyo, Japan).

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas (no. 296) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture, Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anton B P, Heiter D F, Benner J S, Hess E J, Greenough L, Moran L S, Slatko B E, Brooks J E. Cloning and characterization of the BglII restriction-modification system reveals a possible evolutionary footprint. Gene. 1997;187:19–27. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00638-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blattner F R, Plunkett III G, Bloch C A, Perna N T, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Vides J, Glasner J D, Rode C K, Mayhew G F, Gregor J, Davis N W, Kirkpatrick H A, Goeden M A, Rose D J, Man B, Shao Y. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 1997;277:1453–1461. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bougueleret L, Schwarzstein M, Tsugita A, Zabeau M. Characterization of the genes coding for the EcoRV restriction and modification system of Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:3659–3676. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.8.3659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyer H W, Roulland-Dussoix D. A complementation analysis of the restriction and modification of DNA in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1969;41:459–472. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(69)90288-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brassard S, Paquet H, Riym P H. A transposon-like sequence adjacent to the AccI restriction-modification operon. Gene. 1992;157:69–72. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)00734-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dusterhoft A, Erdmann D, Kroger M. Isolation and genetic structure of the AvaII isoschizomeric restriction-modification system HgiBI from Herpetosiphon giganteus Hpg5: M.HgiBI reveals high homology to M.BanI. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:3207–3211. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.12.3207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Erdmann D, Horst G, Dusterhoft A, Kroger M. Stepwise cloning and genetic organization of the seemingly unclonable HgiCII restriction-modification system from Herpetosiphon giganteus strain Hpg9, using PCR technique. Gene. 1992;117:15–22. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90484-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erdmann D, Kroger M. DNA sequence of RM system HgiEI. EMBL Data Library accession no. X55142. 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halling C, Calendar R, Christie G E, Dale E C, Deho G, Finkel S, Flensburg J, Ghisotti D, Kahn M L, Lane K B, Lin C S, Lindqvist B H, Pierson III L S, Six E W, Sunshine M G, Ziermann R. DNA sequence of satellite bacteriophage P4. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:1649. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.6.1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hashimoto-Gotoh T, Tsujimura A, Kuriyama K, Matsuda S. Construction and characterization of new host-vector systems for the enforcement-cloning method. Gene. 1993;137:211–216. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90008-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inoue S, Sunshine M, Six E W, Inoue M. Retronphage φR73: an E. coli phage that contains a retroelement and integrates into a tRNA gene. Science. 1991;256:969–971. doi: 10.1126/science.1709758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ives C L, Nathan P D, Brooks J E. Regulation of the BamHI restriction-modification system by a small intergenic open reading frame, bamHIC, in both Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7194–7201. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.22.7194-7201.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karreman C, de Waard A. Cloning and complete nucleotide sequences of the type II restriction-modification genes of Salmonella infantis. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:2527–2532. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.6.2527-2532.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kita K, Kotani H, Sugisaki H, Takanami M. The FokI restriction-modification system. I. Organization and nucleotide sequences of the restriction and modification genes. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:5751–5766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kita K, Suisha M, Kotani H, Yanase H, Kato N. Cloning and sequence analysis of the StsI restriction-modification gene: presence of homology to FokI restriction-modification enzymes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:4167–4172. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.16.4167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kossykh V, Repyk A, Kaliman A, Buuryanov Y. Nucleotide sequence of the EcoRII restriction endonuclease gene. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;1009:290–292. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(89)90117-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee K F, Shaw P C, Picone S J, Wilson G G, Lunnen K D. Sequence comparison of the EcoHK31I and EaeI restriction-modification systems suggests an intergenic transfer of genetic material. Biol Chem. 1998;379:437–441. doi: 10.1515/bchm.1998.379.4-5.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lereclus D, Agaisse H, Gominet M, Salamitou S, Sanchis V. Identification of a Bacillus thuringiensis gene that positively regulates transcription of the phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C gene at the onset of the stationary phase. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2749–2756. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.10.2749-2756.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindqvist B H, Deho G, Calendar R. Mechanisms of genome propagation and helper exploitation by satellite phage P4. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:683–702. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.3.683-702.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsudaira P. Sequence from picomole quantities of proteins electroblotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:10035–10038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mise K, Nakajima K. Restriction endonuclease EcoO109 from Escherichia coli H709c with heptanucleotide recognition site 5′-PuG/GNCCPy-3′. Gene. 1985;36:363–367. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90192-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newman A K, Rubin R A, Kim S-H, Modrich P. DNA sequences of the structural genes for EcoRI DNA restriction and modification enzymes. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:2131–2139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ørskov I, Ørskov F, Jann B, Jann K. Serology, chemistry, and genetics of O and K antigens of Escherichia coli. Bacteriol Rev. 1977;41:667–710. doi: 10.1128/br.41.3.667-710.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Posfai J, Bhagwat A S, Posfai G, Roberts R J. Predictive motifs derived from cytosine methyltransferases. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:2421–2435. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.7.2421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reimmann C, Moore R, Little S, Savioz A, Willetts N S, Haas D. Genetic structure, function and regulation of the transposable element IS21. Mol Gen Genet. 1989;215:416–424. doi: 10.1007/BF00427038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rina M, Caufrier F, Markaki M, Mavromatis K, Kokkinidis M, Bouriotis V. Cloning and characterization of the gene encoding PspPI methyltransferase from the Antarctic psychrotroph Psychrobacter sp. strain TA137. Predicted interaction with DNA and organization of the variable region. Gene. 1997;197:353–360. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00283-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts R J, Macelis D. REBASE-restriction enzymes and methylases. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:312–313. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schnetz K, Rak B. Cleavage by EcoO109I and DraII is inhibited by overlapping dcm methylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:1623. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.4.1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shore D, Deho G, Tsipis J, Goldstein R. Determination of capsid size by satellite bacteriophage P4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:400–404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.1.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stankevicius K, Povilionis P, Lubys A, Menkevicius S, Janulaitis A. Cloning and characterization of the unusual restriction-modification system comprising two restriction endonucleases and one methyltransferase. Gene. 1995;157:49–53. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)00796-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szilak L, Venetianer P, Kiss A. Cloning and nucleotide sequences of the genes coding for Sau96I restriction modification enzymes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:4659–4664. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.16.4659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tao T, Bourne J C, Blumenthal R M. A family of regulatory genes associated with type II restriction-modification systems. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1367–1375. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.4.1367-1375.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Toba-Minowa M, Hashimoto-Gotoh T. Characterization of the spontaneous elimination of streptomycin sensitivity (Sms) on high-copy-number plasmids: Sms-enforcement cloning vectors with a synthetic rpsL gene. Gene. 1992;121:25–33. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90158-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vaisvilla R, Vilkaitis G, Janulaitis A. Identification of a gene encoding a DNA invertase-like enzyme adjacent to the PaeR7I restriction-modification system. Gene. 1995;157:81–84. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)00793-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van de Guchte M, Daly C, Fitzgerald G F, Arendt E K. Identification of the putative repressor-encoding gene cI of the temperate lactococcal bacteriophage Tuc2009. Gene. 1994;144:93–95. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90209-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilson G, Murray N E. Restriction and modification systems. Annu Rev Genet. 1991;25:585–627. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.25.120191.003101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wood H E, Devine K M, McConnell D J. Characterization of a repressor gene (xre) and a temperature-sensitive allele from the Bacillus subtilis prophage, PBSX. Gene. 1990;96:83–88. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90344-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zakharova M Z, Beletskaya I V, Kravetz A N, Pertzev A V, Mayorov S G, Shlyapnikov M G, Solonin A S. Cloning and sequence analysis of the plasmid-borne genes encoding the Eco29kI restriction and modification enzymes. Gene. 1998;208:177–182. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00637-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]