Abstract

Homeless shelters throughout the U.S. are overcrowded and under-resourced. Families with children face substantial barriers to timely, successful shelter exit, and prolonged shelter stays threaten child mental health. This community-based system dynamics study explored barriers to timely, successful shelter exit and feedback mechanisms driving length of stay and child mental health risk. Group model building – a participatory systems science tool – and key informant interviews were conducted with clients (N = 37) and staff (N = 6) in three family homeless shelters in a Midwestern region. Qualitative content analysis with emergent coding identified key themes feedback loops. Findings indicated overcrowding delayed successful shelter exit; longer stays exacerbated crowding and stress in a vicious cycle. Furthermore, longer stays exacerbated child risk for mental disorder both directly and indirectly via crowding and caregiver stress. Capacity constraints limited families served, while contributing to ongoing unmet need. Future research should investigate the roles of these dynamic feedback relationships in the persistent vulnerability of homeless families. Service design should prioritize interventions that alleviate crowding and subsequent threats to mental health such as private or scattered-site shelter accommodations, affordable child care, and homelessness prevention to facilitate successful shelter exit and mitigate child mental health risk.

Homelessness impacts thousands of families with children in the United States each year. Despite a concerted effort to end family homelessness by 2020, there has been only marginal improvement over the past decade (Henry et al., 2019; U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness, 2015). Families rely on emergency shelters, which remain overburdened and struggle to meet relentless demand. In this context of scarce resources, families and providers must navigate services and consider tradeoffs between imperfect options. Entrenched rates of shelter use, increasing length of stay, stagnant rates of reentry, and persistent indicators of child and family distress suggest ongoing unmet need (Bradley, McGowan, & Michelson, 2018; Evans & Kim, 2007). The formal and informal policies of homeless service agencies, providers, and clients driving these trends have not been fully elucidated, impeding effective system-wide intervention. Greater understanding of the mechanisms driving patterns of homeless service use is needed to develop and implement sustainable systems-level change.

Family Homelessness

Half a million families with children enter shelters each year in the U.S. despite sustained federal and local efforts to end family homelessness (Henry et al., 2018). Shelter entry often signals high levels of family risk. Occurring amid extreme poverty, a homeless episode reflects a culmination of ongoing socioeconomic vulnerability in the face of insufficient affordable housing options (O’Flaherty, 2009). The unpredictability of life in poverty contributes risk for housing instability; a homeless episode may be triggered by a crisis such as job loss, health problem, or domestic violence incident (Culhane, Metraux, Park, Schretzman, & Valente, 2007; Shinn et al., 1998). Family homelessness in the United States impacts households with existing socioeconomic vulnerabilities and few resources to withstand crises (O’Flaherty, 2009).

Homeless threatens child mental health. Up to half of children in homeless shelters display clinically significant behavior problems (Bassuk, Richard, & Tsertsvadze, 2015; Haskett, Armstrong, & Tisdale, 2016). A homeless episode exposes children to a range of adverse experiences that increase stress and interfere with healthy development (Evans & English, 2002; Shonkoff et al., 2012). A large body of research indicates a cumulative effect, whereby greater exposure to adversity translates to greater risk for mental disorder (Evans, Gonella, Marcynyszyn, Gentile, & Salpekar, 2005; Evans & Kim, 2007). Thus, a developmentally-informed homeless system must aim to mitigate the chaos to which children are exposed while homeless, and minimize the time they spend without stable housing.

Homeless Services

The majority of families who enter the homeless system utilize shelters (Henry et al., 2018). Temporary or emergency shelter is intended for brief crisis management and initial housing search support. Shelters may be single- or scattered-site, and sleeping arrangements may include private rooms for families or communal, dorm-style living; families stay on average 30–90 days (Henry et al., 2018). Families typically stay longer than childless individuals, and their needs can be more complex given household sizes (Culhane, Park, & Metraux, 2011). Emergency shelters provide the first line of defense for families who lose their homes; nonetheless, substantial gaps exist in our knowledge of the role shelters play in triaging families and helping them move through services efficiently (Culhane et al., 2011; Mayberry, 2016). Little evidence guides how to best assess and prioritize client needs (Shinn, Greer, Bainbridge, Kwon, & Zuiverdeen, 2013), and service utilization patterns can be driven by policy or availability rather than client need (Culhane et al., 2007; Kushel, Vittinghoff, & Haas, 2001). Efficient assessment and referral are hindered by the complexity of diverse client needs and tremendously scarce resources.

The Need for Innovative Approaches in Homeless Services Research

It is crucial to understand the processes underlying current homeless shelter utilization patterns in order to efficiently meet families’ needs. A systems perspective offers promise by considering the complex dynamics of homelessness, while engaging stakeholders to articulate policy-resistant problems and identify potential solutions (Hovmand, 2014; Sterman, 2000). Families seeking shelter display a range of complex challenges that require more than a “one-size-fits-all” approach, as providers work with limited information and scarce resources (Fowler, Farrell, Marçal, Chung, & Hovmand, 2017). Multiple factors aside from reduced homelessness may reduce rates of homeless service use and service seeking; lack of service availability, family reluctance to enter shelters, or lack of perceived benefits of services may all balance rates of homeless service utilization in spite of persistent housing-related risk across communities. This complexity suggests compensatory feedback processes that are poorly understood, indicating a mismatch between services and needs.

Present Study

The present study probed processes underlying patterns of family homeless shelter use. We applied a system dynamics perspective to address three research questions:

What are the major barriers to timely, successful shelter exit for families?

How do barriers interact to delay successful shelter exit?

How do barriers interact with length of shelter stay to drive child risk for mental health problems over time?

Data were collected through key informant interviews and group model building – a qualitative systems science approach used to elicit rich, firsthand insights into complex processes. Analyses drew upon participant insights to articulate feedback processes driving key outcomes.

Methods

Study Location

The study was conducted in a medium-sized metropolitan area in the Midwestern United States. Homeless shelter use patterns among families with children in the region mirrored national trends; shelter use had remained constant over the past decade, and approximately one in five families reentered shelters within two years. The average length of stay was 50 days – nearly twice HUD’s goal of 30 days.

Recruitment

Participants were recruited from three family homeless shelters. The PI distributed flyers with study information throughout the shelters and visited multiple times before data collection to provide information about the study. Agency staff assisted with informing clients about the study and distributing contact information for the research team. Inclusion criteria for clients included being: a) over age 18, b) a client of one of the three study agencies, and c) the main caregiver for at least one child. For staff, inclusion criteria were: a) being employed at one of the three agencies, and b) having frequent direct contact with clients. Each participant was informed about the study purpose and procedures, and was provided time to review the consent document and ask questions. Participants were compensated with a $20 gift card per session. Study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the principal investigator’s university as well as the National Institute of Mental Health Human Subjects Protection Board.

Group Model Building

Clients and staff were invited to participate in group model building (GMB) sessions. This qualitative, participatory approach elicits diverse perspectives on system structure, stakeholder and researcher assumptions, and formal and informal policies in order to develop insights about system behavior (Hovmand, 2014; Sterman, 2000). Facilitators lead groups in “scripts” designed to elicit complex systems thinking (Andersen & Richardson, 1997; Hovmand et al., 2011). GMB is a promising implementation strategy (Powell et al., 2017) and has been applied to a range of complex problems (e.g. Fowler, Wright, Marçal, Ballard, & Hovmand, 2018; Williams, Colditz, Hovmand, & Gehlert, 2018). Key strengths of GMB include the emphasis on community-engaged procedures for eliciting complex systems thinking (Hovmand, 2014). The present study utilized GMB and key informant interviews to develop a causal feedback theory of factors driving persistent rates of shelter use, length of stay, and child risk for mental disorder among families in homeless shelters. Client participants (N = 37) were invited to take part in two one-hour GMB sessions (one initial and one follow-up). Staff members participated in GMB sessions (N = 3) or semi-structured interviews (N = 3).

Variable elicitation:

This script generated ideas about key factors in service-related decision-making processes (Luna-Reyes et al., 2006). The facilitator presented an initial problem statement to the group – “It is hard to find appropriate homeless services” – and gave examples of variables such as “long waitlists for services,” “provider burnout,” or “frustration” that might be important based on prior research. Participants spent 5–10 minutes individually writing down what they perceived to be important causal or outcome variables. The group then reconvened and took turns presenting their variables in a “round-robin” fashion. The facilitator asked probing questions so that each variable was clearly articulated and understood by everyone in the group.

Graphs over time.

This script captured changes in variables over time. The facilitator provided sheets of paper with x and y axes displayed. The x axes were labeled from a minimum of Day of Entry to a maximum of Day of Exit to capture average behavior over the duration of a typical shelter stay. The y-axes were labeled from Low to High to capture general trends in key variables rather than specific parameter values. Participants were asked to provide graphs of key variables over time as well as bivariate graphs illustrating the relationships between two variables – e.g. how client stress was related to shelter crowding. Again, participants presented graphs to the group; facilitators posed clarifying questions so the “story” of each variable or relationship was understood by the group.

Initiating and elaborating a causal loop diagram.

This script used the variables elicited above to develop a formal theoretical model (causal loop diagram; CLD) of how homeless families and providers made decisions about navigating services (Richardson & Andersen, 1995; Vennix, 1995). After displaying all variables on a whiteboard or large flipchart paper, the facilitator asked participants to describe causal connections between variables. The modeler drew arrows between variables, with + or − signs to indicate the directionality of the effect.

Causal mapping with seed structure.

In follow-up sessions, the facilitator presented a seed structure based on initial CLDs (Luna-Reyes et al., 2006). Participants provided feedback on what was right, wrong, or incomplete. With assistance from two participant co-facilitators, the facilitation team revised the seed structure based on participant input. Particular emphasis was placed on identifying feedback relationships among variables, indicated by reinforcing loops (vicious or virtuous cycles) or balancing loops (compensatory or equilibrium-seeking processes). Causal links elicited from participants connected variables to articulate feedback loops driving key outcomes: crowding, length of stay, and child risk for mental health problems (Hovmand, 2014).

Key Informant Interviews

Interviews were conducted with three staff members serving in various roles at the sampled agencies. Job responsibilities included organizational leadership, facilities and operational tasks, and case management; all three had direct contact with clients; the staff member in a leadership position also had intimate understanding of the governance structure, funding mechanisms, and policies of the local homeless services system. Each key informant completed a 45- to 60-minute semi-structured interview that covered his or her experiences working in the agency.

Analytic Approach

Data were analyzed in multiple phases, and model validation occurred iteratively throughout data collection and analyses. Outputs from initial group model building sessions were reviewed and summarized in memos by at least two members of the research team. Key variables were identified using content analysis with emergent coding (Stemler, 2001). Coding was conducted independently by two researchers to identify themes, and reviewed for convergence (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). Any coding discrepancies between the two researchers were resolved through discussion, review of session memos and causal loop diagrams, and consultation of existing literature resolved coding discrepancies. Follow-up GMB sessions were used to seek participant feedback on initial causal structures and check researcher interpretations (Hovmand, 2014). The final causal loop diagram incorporated key themes and causal links identified from GMB sessions and the subsequent coding process. The full causal model was revised through feedback from subsequent GMB sessions and consultation with existing literature.

Results

Participants

Client GMB participants included 37 homeless clients with children. They were overwhelmingly female (91%) and Black (87%), and two-thirds were first-time shelter clients (65%). The mean age was 39.6 (SD = 13.0) years. Families on average included 2.5 children (SD = 1.8), family size ranged from 1 to 5 children. Client GMB sessions were supplemented with additional sessions and key informant interviews with agency staff in various roles. Staff participants were all female and primarily Black (83%). Agency employment tenures ranged from five to 24 years. Interviews were conducted with an executive director, a shelter manager, and a case manager who offered perspectives on client experiences of shelter stays and their own experiencing as providers.

Major Themes

A number of key themes emerged from group model building sessions and key informant interviews with clients and staff members.

Crowding.

Crowding and lack of privacy that accompanied shelter living was challenging for many caregivers. Clients felt that the undesirable conditions in shelters increased stress, making them feel less capable and more emotionally drained. Crowding also limited time with caseworkers and availability of resources, which made it more difficult to make progress toward shelter exit. Clients described the push-and-pull feeling of wanting to adapt to the shelter in order to feel more at home and reduce their stress, but also not wanting to let themselves “get comfortable;” they believed this would reduce their drive to make progress toward their goals.

Key informants confirmed the link between crowding and stress, indicating that when shelters feel below 20% vacancy, it began to “feel” overcrowded, impacting caregiver, child, and staff mental health. Key informants discussed the pressures that crowding placed on staff, who were reluctant to let families stay longer than the indicated 30 days when calls increased: “We’re always full… We get hotline calls all day long. That forces us to move people as quickly as we can.” Another staff member echoed the problem with crowding, explaining that it had been compounded by recent policy changes that shifted funding away from transitional housing programs: “We need more ‘next-step’ beds. Everything would be in its proper queue. We’ve become the transitional housing.” This phenomenon also forced more difficult decisions about client exit, as clients typically had to move directly shelter to independent housing, without the intermediate supports of a transitional housing setting. Staff shared that lack of this “step-down” approach increased likelihood of subsequent homelessness and shelter reentry. Key informants believed more accurate assessment and targeted referrals would reduce the burden on shelters, ease bottlenecks at system entry, and help families stabilize more quickly.

Length of Stay.

Clients confirmed a relationship between length of shelter stay and that the longer a family stayed in shelter, the more likely they were to experience a decline in empowerment, and thus feel less capable of regaining independent housing quickly; this constituted a “vicious cycle” that reinforced longer stays and delayed timely exit.

Staff believed caregiver stress increased over time – particularly as their target exit dates approached and the prospect of having to leave the shelter became more “real” to them:

As soon as people walk in here, they want to know how long they can stay. When they approach that time, they start getting stressed. They start asking [other clients], ‘How long have you been here? How long have you been here? Why do I have to leave?’

Staff also described a feedback relationship between length of stay and increased stress:

If people stay longer and aren’t making progress, their stress goes up. ‘The longer I’m not making my goal, the more stressed I am because I’m stuck here.’ People get comfortable, but even in that comfortability they get stressed because they see other people making progress.

Caregiver Mental Health.

Caregivers emphasized the emotional strain they experienced during their shelter stay, describing it as a function of the chaos of living in crowded quarters, the guilt and stress of parenting, and the limited resources offered by the shelters. Rating her stress on a scale from one to 10, one woman stated, “I’m at a 12.” There was consensus among the group that their stress levels increased throughout the duration of the stay; caregivers reported stress intensified over time, and that stress increased as crowding increased. One woman described:

The emotional strain on you, the mental strain on you, the social strain on you - I don’t know if I have what it takes to fight through everything just to get back on my feet as an adult to get what everyone wants as an adult: to get your own place for you and your children.

A father discussed how safety and stability were integral to his ability to make progress toward returning to housing:

The shelter should make you feel a sense of stability, because you’re already so stressed. If I’m going for one chaotic situation to one that’s even more chaotic, where am I going to have that sense of peace and understanding to hit my points?

Caregivers talked extensively about their own internal motivation and self-efficacy, captured as empowerment. Clients felt a sense of responsibility to stay focused on securing a stable future for their children. One woman stated, “[Empowerment] is a sense of motivation, accomplishment, getting yourself out of a bad situation… Empowerment means moving forward.” Another defined empowerment as: “A sense of ownership, owning up to your role in coming here. Deal with it, process it, move on.” Clients expressed pragmatism in discussing the effort required to move forward. One said:

It falls on the shelter and also falls on us. It’s our mentality. It’s going to be how you want it to be. You’ve got to keep moving… It’s on me to make it what I want it to be.

A young mother of a son with a physical disability said:

I had him. The state didn’t have him. So I have to take care of him. […] As black people, we can’t expect things to come to us without putting anything in.

Participants emphasized the significance of internal motivation in concert with concrete resources from the homeless services system as essential components of successful shelter exit. Many felt too much of service delivery applied a “one-size-fits-all” approach without acknowledging the complexity of families’ circumstances and needs. In one agency, for example, clients were not allowed to enter the building 8am- 4pm even if they worked nights, lacked transportation, or suffered from depression that made it difficult to motivate action.

Child Risk for Mental Disorder.

Caregivers nearly uniformly expressed concerns for the effects of the shelter stay on children’s well-being. Parenting posed particular challenges as caregivers attempted to manage children’s emotional and behavioral well-being in the shelter setting. Caregivers in larger families struggled to follow shelter rules requiring them to direct supervise children at all times while in the shelter. Parents felt disempowered to discipline their children, who observed their parents being reprimanded by staff and were thus not motivated to respect parents’ authority. Furthermore, parents felt “under a microscope” and worried about being reported to Child Protective Services. A staff member explained:

They want to discipline their kids, but we can’t let them slap or hit or kick the kids. We are mandated reporters. So parents get frustrated that they can’t control their kids.

Caregivers felt that their stress in managing these dynamics contributed to risk for children developing lasting emotional and behavioral problems.

Children’s emotional and behavioral problems tended to increase over time as they became more aware of and frustrated by their surroundings; caregivers noted increased “acting out” and other behavior problems indicative of mental health risk the longer children spent in the shelter. Crowding also affected child mental health; a staff member estimated that when the shelter got more crowded, “Moms are stressed, kids are stressed, staff is stressed” and, as a mother explained, “When kids are stressed, they act out… [They get] very needy, looking for attention.” In addition to crowding and length of stay contributing to child mental health risk, caregivers and staff members described a reciprocal relationship between caregiver mental health and child mental health. A caregiver explained how her children had become increasingly needy throughout the shelter stay, which contributed to her stress and made her more likely to lose her patience. A staff member described, “Mom’s stress affects the child’s stress; it works both ways.” The challenges of parenting for caregivers were compounded by the shelter conditions, unrelenting stress, and uncertainty around return to stable housing.

Causal Theory

Insights from primary data collection were synthesized into unified causal theory of families’ experiences of homeless shelters. Key constructs comprised feedback loops that described endogenous processes. Feedback loops made up a larger unified causal theory supported by a combination of insights from key informant interviews, GMB sessions, and prior literature on homeless services and families’ experiences of shelters (Table 2).

Table 2.

Key causal links with sources

| Causal link | Source |

|---|---|

| Crowding increases stress | GMB, key informant interview, Pable 2012; Evans & English, 2002 |

| Length of stay increases stress | GMB, key informant interview |

| Stress erodes empowerment | GMB; Banyard & Graham-Bermann, 1995 |

| Empowerment reduces length of stay | GMB, key informant interview |

| Length of stay erodes self-efficacy | GMB; Banyard & Graham-Bermann, 1995 |

| Demand for services increases pressure on caseworkers | GMB; key informant interview |

| Importance of considering “empowerment” in service delivery | Tischler, Edwards, & Vostanis 2009 |

Note: GMB = Group Model Building

Key Constructs

System capacity referred to the number of available units for families. Families in shelter relative to capacity indicated the extent of crowding. Participants uniformly stated agencies were always full or nearly full. Staff estimated that when the proportion of occupied spots exceeded 75–80% of total capacity, agencies began to “feel” overcrowded, affecting stress levels. Length of stay referred to the time families spent in shelters in a given homeless episode; staff estimated the average length of stay as 50–60 days, although some families stayed up to 15 months.

Caregivers described empowerment as a key component of their ability to return to stable housing. This construct was described variably as: “self-empowerment,” “strong foundation,” and “commitment,” but all emphasized determination, believing in one’s ability to pursue self-sufficiency, and being a good parent. This was labeled empowerment in the model based on prior explorations of similar qualities and their relation to homeless mothers’ perceived capabilities (Banyard & Braham-Bermann, 1995; Peterson, 2014).

Pressure on staff was elicited from both staff members and clients, who noted that caseworkers felt pressure from funders, agency policy, and overwhelming demand to move people through services as quickly as possible. Clients were allowed to stay beyond the typical timelines (30 days in shelter and 2 years in transitional housing) if they were perceived to be making progress; “progress” was a subjective assessment, and pressure to move clients more quickly intensified when hotline calls increased.

Caregiver stress indicated the amount of emotional strain caregivers experienced in services. Caregivers self-reported rated stress levels throughout their shelter stays on a scale of 1–10.

Child risk encompassed child risk for mental health, as defined by caregivers and prior research on the cumulative effects of exposure to adversity (Evans & Kim, 2007). This construct incorporated children’s exposure to the adversity of living in a shelter – including the heightened stress, environmental chaos, lack of stable home, and distressed caregivers – and the theoretically indicated risk for emotional and behavioral disorder (Evans & English, 2002; Evans & Kim, 2007) and was operationalized as a function of length of stay and shelter crowding.

Key causal links were reviewed independently by two researchers and cross-checked against existing literature for consistency and validity. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion, further consultation of literature, and consultation with key content experts. Causal links that created feedback loops were identified and labeled. Feedback loops described the dynamics underlying patterns of service use and family well-being.

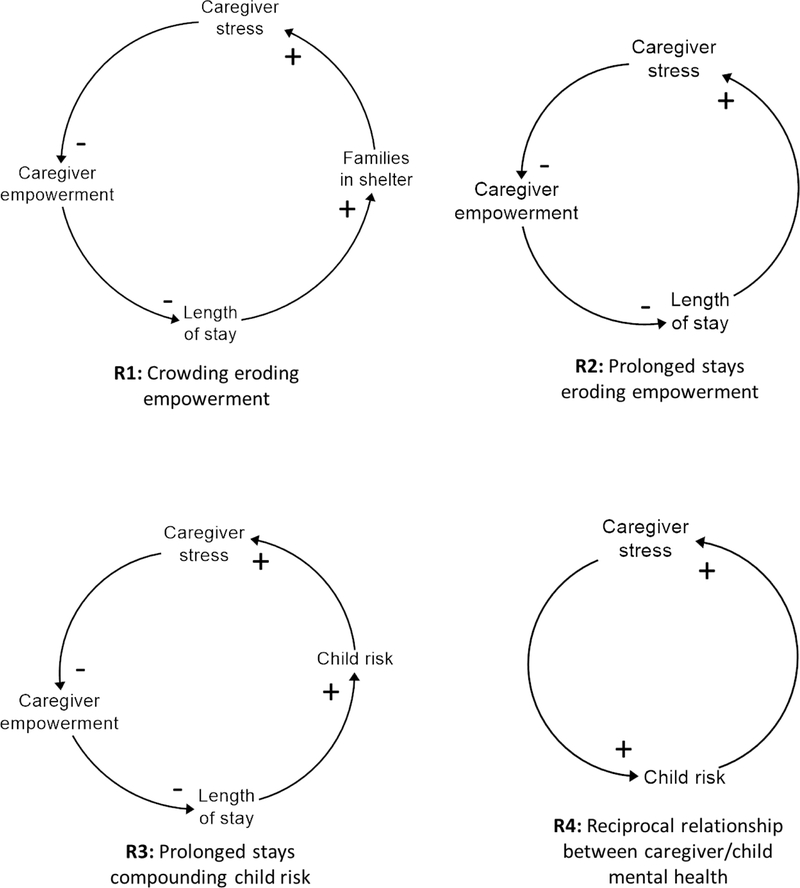

Feedback Loops: Reinforcing

Four major reinforcing loops created vicious or virtuous cycles impacting the number of families in services, length of stay, and child risk for mental disorder (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Reinforcing loops

R1:

“Crowding eroding empowerment.” Caregivers, staff, and prior literature concurred that when more families entered the system and services became more crowded, client stress increased; this eroded empowerment. Families who were less empowered were less likely to make progress toward stable housing and move through services quickly; longer stays resulted in more families in services over time and thus more crowding.

R2:

“Prolonged stays compounding stress.” Caregivers and providers alike described a sense of stress, frustration, and defeat emerging the longer clients stayed in shelter. Repeat rejections from landlords or housing programs elevated stress that drove down empowerment. Lower empowerment further contributed to longer stays as caregivers felt helpless to engage with services and hopeless about making progress.

R3:

“Prolonged stays compounding child risk for mental health problems.” Caregivers’ and providers’ insights converged regarding the impact of shelter stays on child risk. Child stress increased throughout shelter stays, as they faced prolonged exposure to the chaotic environment and their caregivers’ distress. Participants agreed that child behavior problems increased over time, thus contributing to caregiver stress and the overall complexity of the family’s needs.

R4:

“Reciprocal relationship between caregiver and child mental health.” Both staff and caregivers described a feedback cycle in which caregivers worried about children’s mental health, and children sensed and were adversely affect by caregivers’ stress.

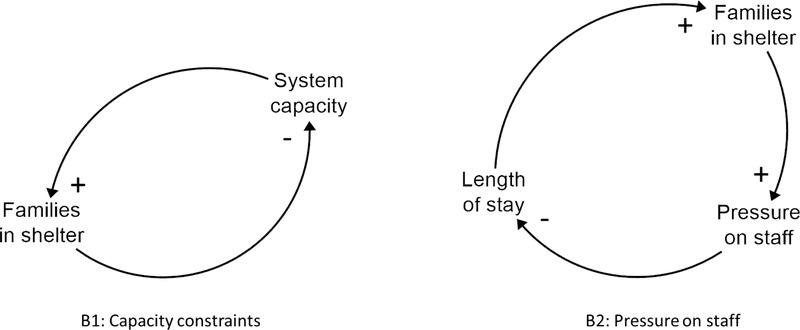

Feedback Loops: Balancing

Few reinforcing processes can persist forever. For example, crowding can worsen to a point, but only so many families can physically enter the shelter. Two balancing loops acted as checks on the reinforcing loops above (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Balancing loops

B1:

“Capacity constraints.” This loop is a simple story of supply and demand. The more families who entered services, the fewer services were available for new families. When families left, in contrast, more services became available allowing for more entries and reentries.

B2:

“Pressure on staff.” With more families entering services, staff members were pressured both internally (by agency policy) and externally (by funders) to move families more quickly through services, reducing the average length of stay and overall families in services. In this scenario, decisions to exit clients were driven by capacity constraints rather than client needs or readiness, thus reducing the likeliness of successful shelter exit to stable, long-term housing.

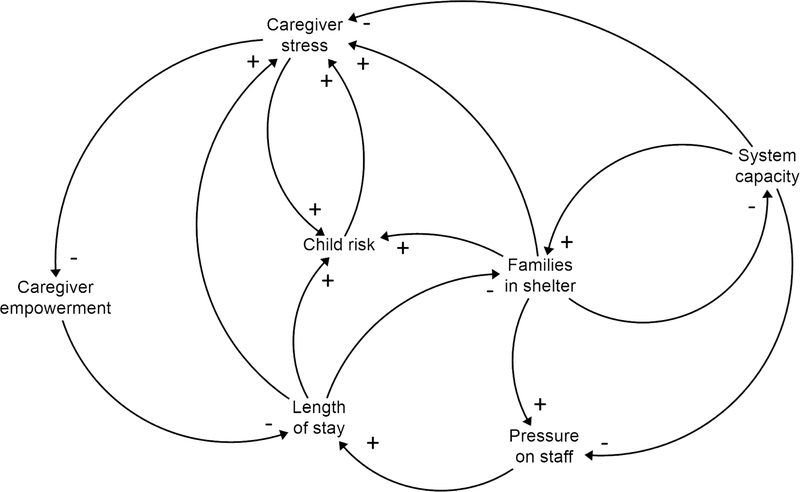

The loops described above comprised a broader theory describing families’ experiences in homeless shelters (Figure 3). Balancing and reinforcing loops interacted to indicate the complexity of serving families in shelters, and point to opportunities for intervention.

Figure 3.

Full causal feedback map of homeless shelter service delivery

Discussion

The present study engaged providers and clients to explore processes driving length of shelter stay, successful exits, and child mental health risk among families in homeless shelters. The innovative participatory systems approach elicited rich “on-the-ground” insights that informed development of a complex causal feedback theory. Stakeholders highlighted the dynamic interactions between service delivery systems and psychological processes. With shelters constantly full to capacity, both staff and clients reported that overcrowded conditions increased client stress and eroded the empowerment needed to make progress toward shelter exit. This delayed return to stable housing, as families’ needs were compounded by the stress caused by shelter conditions. A counterintuitive insight that emerged from group model building was that crowding could also accelerate client exit via increased pressure on staff members providing services in the context of extreme scarcity; when exit decisions were driven by capacity constraints rather than client readiness, it was less likely that families would exit shelters to sustainable stable housing and the risk for subsequent reentry increased. Thus, length of stay and successful shelter exit were impacted both positively and negatively by crowding. Complex dynamics linking service use, client housing decisions, and child mental health unfolded in this context of scarcity.

The significance of stress and its implications for mental health, parenting, and housing stability emerged strongly from modeling sessions. Clients described feeling crippled by stress due to crowded conditions, demands from children, paperwork for housing applications, and conflicts with other clients or staff members. Mental health problems figured prominently into discussions of the shelter experience. Although not directly assessed for mental health disorders, several participants disclosed diagnoses of depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder – a trend supported by prior literature that has established high rates of mental disorder among mothers experiencing housing crises (Marçal, 2018). Mental disorder created stigma and shame compounded by caregivers’ homeless status, which interfered with ability to seek independent housing and engage in positive parenting. Findings converged with prior research suggesting homelessness and entrance into homeless services pose significant barriers to the routines of positive parenting, interfering with caregiver autonomy and parent-child attachment (Bradley et al., 2018; Mayberry et al., 2014). Both clients and staff felt underequipped to manage the challenges posed by prevalent depression and anxiety among shelter populations, and felt these posed concrete obstacles to efficient return to stable housing.

Caregivers and providers emphasized the impact of inefficiencies in service delivery on child mental health. The stress of the shelter environment interfered with healthy child emotional and behavioral development, which increased child risk for mental health problems, strained caregivers, and increased families’ needs (Evans et al., 2015; Evans & Kim, 2007; Haskett et al., 2015). Child mental health was threatened by a range of factors including overcrowded conditions (Solari & Mare, 2012), caregiver stress (Conger et al., 1992, 1994), and prolonged exposure to homelessness (Shonkoff et al., 2012). Thus, efforts to improve efficiency of service delivery and support child well-being are intertwined. Emerging research has shown promise for using systems approaches to improve services for homeless and insecurely housed families (Fowler et al., 2017, 2018), but little empirical evidence guides the implementation of developmentally-informed services into the homeless system. Future research must consider children’s unique developmental trajectories when designing and testing interventions to improve outcomes for homeless families.

Finally, the study highlighted the immense socioeconomic disparities that persist by race across the U.S. The client sample for the present study was nearly exclusively African American, reflecting the disproportionate representation of minority groups among those experiencing homelessness (Henry et al., 2018). American cities remain highly racially segregated (Fischer & Massey, 2004), presenting Black Americans with increased barriers to securing and maintaining stable housing. While race emerged in the present study, future research should specifically explore the informal mechanisms employed by minority populations to cope with discrimination in the search for housing.

Findings must be considered in light of limitations. Data were collected in three homeless shelters in urban and suburban areas of the Midwestern U.S. It is possible dynamics differ in agencies serving more sparsely populated rural regions. The study only included families who had entered homeless shelters, thus excluding those at risk but not yet homeless, or who had either been unable or unwilling to enter a shelter. Given overwhelming demand for homeless services in the region, only a fraction of homeless families were represented in shelters; thus, findings may not be generalizable to homeless families more broadly. Furthermore, limited time was spent with participants; more in-depth conversations over longer periods of time may have yielded additional insights. Future research should employ additional methods such as in-depth interviewing with clients to further probe individual decision-making processes that underlie service use and housing patterns. Finally, literature on child development suggests a compensatory process by which resilience counteracts detrimental effects of adversity that did not emerge from participants in the current study (Engle, Castle, & Menon, 1996; Patterson, 2002).

Limitations notwithstanding, a number of practical implications emerge from the present findings. First, homeless shelters must contend with the overwhelmingly negative effects of crowding on staff and client mental health; the strain of living in communal quarters was so intense that it actually hindered service quality and successful shelter exits. Scattered-site shelters or increased transitional housing programs could alleviate some of the overcrowding issues experienced by current shelter models. Private quarters in single-site shelters could increase access to privacy and provide some relief from the stressors of communal living. Second, on-site child care and counseling could reduce parenting stress for caregivers and provide early intervention for children with emerging mental health risks. Interrupting the vicious cycle of increasing caregiver and child stress could serve as a leverage point to promote mental health in both caregivers and children, in turn allowed clients to benefit more from work with case managers and other shelter staff. At the community level, increased investment in homelessness prevention interventions such as rental or utility assistance, landlord mediation, and tenant right-to-counsel in eviction hearings could reduce the inflow of families into the homeless system, alleviating crowding and preventing children’s exposure to the adversity of homelessness.

The present study highlights the importance of including diverse stakeholders in the process of developing theoretical understanding of complex problems. Many of the mechanisms driving stagnation and inefficiency in service delivery are hidden from view – outside “official” agency policies and procedures. Improving system performance to promote family and child well-being must take these mechanisms into account in order to disrupt entrenched patterns of system behavior. The all-encompassing nature of homeless services make them unlike many other social services such as weekly counseling or support groups; thus the feedback of shelter conditions on stress, self-efficacy and length of stay is likely more influential on the system as a whole. Future researchers and providers must consider this feedback when designing services, assessing families, and delivering interventions.

Table 1.

Key themes and variables from GMB and key informant interviews

| Variables | Example Quotations |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Caregiver stress | “The emotional strain on you, the mental strain on you, the social strain on you - I don’t know if I have what it takes…” - Caregiver “It makes you crazy. You feel helpless. It’s just never-ending.” – Caregiver |

| Empowerment | “It’s a sense of motivation, accomplishment, getting yourself out of a bad situation. Empowerment means ‘moving forward.’” - Caregiver “Either you’re gonna become resilient, or you gonna fall and crumble.” – Caregiver |

| Child mental health risk | “Moms are stressed, kids are stressed, staff is stressed.” - Caregiver “Mom’s stress affects the child’s stress; it works both ways.” – Staff |

| “When kids are stressed, they act out…very needy, looking for attention” – Caregiver

“They want to discipline their kids, but we can’t let them slap or hit or kick the kids. We are mandated reporters. So parents get frustrated that they can’t control their kids.” – Staff |

|

| Complex family needs | “[We] have very different needs and that makes it hard for caseworkers to provide for needs.” – Caregiver

“Length of stay depends on: how complicated are their needs…how many steps do they have to take?” – Staff |

| Crowding | “When it’s more crowded, it’s definitely more stressful, especially for the children.” – Staff “We’re always full… We get hotline calls all day long. That forces us to move people as quickly as we can.” – Staff “We like them out in 90 days but some stay up to a year… If we have space, they can stay.” – Staff |

| Available housing resources | “Clients want to just put their names on any list, [they] don’t necessarily know the criteria or realize how long the wait will be and that they shouldn’t count on it.” – Staff “It’s so hard to get [a housing voucher], but it’s even harder to use it.” – Caregiver “All of the affordable housing is in a rough neighborhood.” – Caregiver |

References

- Andersen DF & Richardson GP (1997). Scripts for group model building. System Dynamics Review, 13, 107–29. doi:AID-SDR120>3.0.CO;2–7. [Google Scholar]

- Banyard VL & Graham-Bermann S (1995). Building an empowerment policy paradigm: Self-reported strengths of homeless mothers. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 65, 479–91. doi: 10.1037/h0079667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley C, McGowan J, & Michelson D (2018). How does homelessness affect parenting behavior? A systematic critical review and thematic synthesis of qualitative research. Clinical Child & Family Psychology Review, 21, 94–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Elder GH, Lorenz FO, Simons RL, & Whitbeck LS (1992). A family process model of economic hardship and adjustment of early adolescent boys. Child Development, 63, 526–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Ge X, Elder GH, Lorenz FO, & Simons RL (1994). Economic stress, coercive family process, and developmental problems of adolescents. Child Development, 65, 541–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW & Creswell JD (2018). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Washington, D.C.: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Culhane DP, Metraux S, Park JM, Schretzman M, & Valente J (2007). Testing a typology of family homelessness based on patterns of public shelter utilization in four U.S. jurisdictions: Implications for policy and program planning. Housing Policy Debate, 18, 59–67. doi: 10.1080/10511482.2007.9521594 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Culhane DP, Park JM, & Metraux S (2011). The patterns and costs of service use among homeless families. Journal of Community Psychology, 39(7), 815–825. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20473 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Engle PL, Castle S, & Menon P (1996). Child development: Vulnerability and resilience. Social Science & Medicine, 43, 621–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW & English K (2002). The environment of poverty: multiple stressor exposure, psychophysiological stress, and socioemotional adjustment. Child Development, 73, 1238–1248. doi:10.1111%2F1467-8624.00469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, Gonella C, Marcynyszyn LA, Gentile L, & Salpekar N (2005). The role of chaos in poverty and children’s socioemotional adjustment. Psychological Science, 16, 560–565. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.01575.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, & Kim P (2007). Cumulative risk exposure and stress dysregulation. Psychological Science, 18(11), 953–958. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.02008.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer MJ & Massey DS (2004). The ecology of racial discrimination. City & Community, 3 221–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1535-6841.2004.00079.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler PJ, Farrell AF, Marçal KE, Chung S, & Hovmand PS (2017). Housing and child welfare: Emerging evidence and implications for scaling up services. American Journal of Community Psychology, 60, 134–144. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler PJ, Wright K, Marçal KE, Ballard E, & Hovmand PS (2018). Capability traps impeding homeless services: A community-based system dynamics evaluation. Journal of Social Service Research, doi: 10.1080/01488376.2018.1480560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskett ME, Armstrong JM, & Tisdale J (2015). Developmental status and social–emotional functioning of young children experiencing homelessness. Early Childhood Education Journal. doi:/ 10.1007/s10643-015-0691-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henry M, Bishop K, de Sousa T, Shivji A, & Watt R (2018). The 2018 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress. Part 2: Estimates of Homelessness in the United States. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. [Google Scholar]

- Henry M, Watt R, Mahathey A, Ouellette J &, Sitler A (2019). The 2019 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress Part 1: Point-in-Time Estimates of Homelessness. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. [Google Scholar]

- Hovmand PS (2014) Community Based System Dynamics. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kushel MB, Vittinghoff E, & Haas JS (2001). Factors associated with the health care utilization of homeless persons. JAMA, 285, 200–206. doi:/ 10.1001/jama.285.2.200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna-Reyes LF, Martinez-Moyano IJ, Pardo TA, Cresswell AM, Andersen DF, & Richardson GP (2006). Anatomy of a group model-building intervention: Building dynamic theory from case study research. System Dynamics Review, 22(4), 291–320. [Google Scholar]

- Marçal K (2018). Timing of housing crises: Impacts on maternal depression. Social Work in Mental Health, 16, 266–83. doi: 10.1080/15332985.2017.1385565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberry LS (2016). The hidden work on exiting homelessness: Challenges of housing service use and strategies of service recipients. Journal of Community Psychology, 44, doi: 10.1002/jcop.21765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberry LS, Shinn M, Benton JG, & Wise J (2014). Families experiencing housing instability: The effects of housing programs on family routines and rituals. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84, 95–109. doi: 10.1037/h0098946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Flaherty Brendan. 2009. What shocks predict homelessness? Columbia University, Department of Economics, Discussion Papers: 0809–14. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson JM (2002). Understanding family resilience. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58, 233–246. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson NA (2014). Empowerment theory: Clarifying the nature of higher-order multidimensional constructs. American Journal of Community Psychology, 53, 96–108. doi: 10.1007/s10464-013-9624-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell BJ, Beidas RS, Lewis CC, Aarons GA, McMillen JC, Proctor EK, & Mandell DS (2017). Methods to improve the selection and tailoring of implementation strategies. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research 44, 177–194. doi: 10.1007/s11414-015-9475-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinn M, Greer AL, Bainbridge J, Kwon J, & Zuiverdeen S (2013). Efficient targeting of homelessness prevention. American Journal of Public Health, 103, 324–330. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinn M, Weitzman BC, Stojanovic D, Knickman JR, Jiménez L, Duchon L…Krantz DH (1998). Predictors of homelessness among families New York City: From Shelter request to housing stability. American Journal of Public Health, 88, 1651–57. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.88.11.1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, Garner AS, Siegel BS, Dobbins MI, Earls MF, Garner AS….Wood DL (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics, 129, e232–e246. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solari CD & Mare RD (2012). Housing crowding effects on children’s wellbeing. Social Science Research, 41, 464–476. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2011.09.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stemler S (2001). An overview of content analysis. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 7. 137–146. [Google Scholar]

- Sterman J (2000). Business Dynamics: Systems Thinking and Modeling for a Complex World. Irwin\McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness. (2015). Opening Doors: Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness. Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- Vennix J (1995). Group Model Building: Facilitating Team Learning Using System Dynamics. Chichester: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Williams F, Colditz GA, Hovmand PS, & Gehlert S (2018). Combining community-engaged research with group model building to address racial disparities in breast cancer mortality and treatment. Journal of Health Disparities Research & Practice, 1, 160–178. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]