Abstract

This qualitative research aimed to examine Senegalese disabled women’s access to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services and information. Poor access to SRH services and information can lead to a range of negative consequences, including poor sexual, reproductive, and maternal health outcomes; rights violations; and impacts on mental health and livelihoods. Disabled women, who are marginalised and stigmatised both by their gender and their disability, may face significant barriers in access, but a full understanding of this access is lacking due to a dearth of research on this population. We used a snowball sampling method to identify 31 women with physical motor disabilities in the Dakar region, and we interviewed them from October to December 2019 using a semi-structured questionnaire. We analysed interviews using thematic analysis, which we complemented with frequency calculations and graphs where appropriate. Respondents reported having difficulties accessing SRH services and information because of structural inaccessibility within health care establishments, financial limitations, inaccessible transportation and far-away health establishments, long wait times in health care establishments, and prejudices and discrimination from health providers. Women had low knowledge of STIs, but were generally well-informed on different types of contraception, felt that accessing SRH information is easier than accessing services, and wished to see improvements in the Senegalese health care system specifically geared towards people with disabilities. Evidence from this research can inform policy and programmatic efforts to improve disabled women’s access to SRH services and information.

Keywords: disability, sexual and reproductive health, Senegal, women’s health, accessibility, carte d’égalité des chances

Résumé

Cette recherche à méthodologie qualitative portait sur l’accès des Sénégalaises handicapées aux services et à l’information de santé sexuelle et reproductive (SSR). Le faible accès aux services et à l’information de SSR peut aboutir à un éventail de conséquences négatives, notamment un mauvais état de santé sexuelle, reproductive et maternelle; des violations des droits; et des impacts sur la santé mentale et les moyens de subsistance. Les femmes handicapées, qui sont marginalisées et stigmatisées, aussi bien du fait de leur sexe que de leur invalidité, se heurtent parfois à d’importants obstacles dans l’accès, mais une totale compréhension de cet accès fait défaut en raison de la rareté des recherches sur cette population. Nous avons utilisé une méthode d’échantillonnage dite “boule de neige” pour identifier 31 femmes porteuses de handicaps physiques et moteurs dans la région de Dakar, et nous les avons interrogées à l’aide d’un questionnaire semi-structuré. Nous avons analysé les entretiens avec une analyse thématique, que nous avons complétée par des calculs et graphiques de fréquence, le cas échéant. Les répondantes ont indiqué qu’elles avaient des difficultés à bénéficier des services et informations de SSR du fait de l’inaccessibilité structurelle des établissements de santé, de limitations financières, d’un manque de moyens de transports accessibles et de l’éloignement des établissements de santé, des longs délais d’attente dans les établissements de santé, ainsi que des préjugés et de la discrimination de la part des prestataires de santé. Les femmes connaissaient mal les IST, mais étaient en général bien informées des différents types de contraception. Elles estimaient qu’il était plus facile d’avoir accès aux informations sur la SSR que d’avoir accès aux services, et souhaitaient voir des améliorations dans le système de santé sénégalais, pensées spécifiquement pour les personnes handicapées. Les données provenant de cette recherche peuvent guider les activités politiques et programmatiques destinées à élargir l’accès des femmes handicapées aux services et informations de SSR.

Resumen

Esta investigación de metodología cualitativa tenía como objetivo examinar el acceso de las mujeres senegalesas discapacitadas a servicios e información de salud sexual y reproductiva (SSR). El mal acceso a servicios e información de SSR puede causar una variedad de consecuencias negativas, tales como malos resultados de salud sexual, reproductiva y materna; violaciones de derechos; e impactos en la salud mental y en el sustento. Las mujeres con discapacidad, que son marginadas y estigmatizadas tanto por su género como por su discapacidad, podrían enfrentar barreras significativas al acceso, pero se carece de una comprensión total de este acceso debido a la escasez de investigaciones sobre esta población. Utilizamos el método de muestreo de bola de nieve para identificar a 31 mujeres con discapacidad físico-motriz en la región de Dakar y las entrevistamos utilizando un cuestionario semiestructurado. Analizamos las entrevistas utilizando análisis temático, que suplementamos con cálculos y gráficos de frecuencia, si procedía. Las entrevistadas informaron tener dificultades para acceder a servicios e información de SSR debido a la inaccesibilidad estructural dentro de los establecimientos de salud, limitaciones financieras, transporte inaccesible y establecimientos de salud muy lejanos, largos tiempos de espera en establecimientos de salud, y prejuicios y discriminación de prestadores de servicios de salud. Las mujeres tenían poco conocimiento de ITS, pero generalmente estaban bien informadas sobre diferentes tipos de anticoncepción, creían que acceder a la información sobre SSR es más fácil que acceder a los servicios, y deseaban ver mejoras en el sistema de salud senegalés dirigidas específicamente a las personas con discapacidad. La evidencia de esta investigación puede informar los esfuerzos normativos y programáticos por mejorar el acceso de las mujeres con discapacidad a los servicios e información de SSR.

Introduction

Poor access to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services and information for women around the world can result in unwanted and/or mistimed pregnancies, poor maternal health, and high rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) including HIV/AIDS, as well as other negative consequences on health, livelihoods and economic success.1 Beyond preventing negative consequences, access to SRH services and information is a fundamental right for all humans that should be protected and upheld. Marginalised people who experience social exclusion, stigma, and discrimination, such as people with disabilities, are more likely to have poor access to these services and information.2 In Senegal, disabled women are doubly marginalised, by both their gender and their disability, yet we lack a full understanding of the state of their access to SRH services and information due to a dearth of research on this population.

The importance of studying this key population cannot be ignored; multilateral development agreements such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which Senegal adopted, show a global concerted effort to improve health equity and access for all. Within the SDGs, people with disabilities are a focal point, and making “sexual and reproductive health-care facilities accessible for persons with disabilities” (p. 30) is recommended by the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs and confirms the importance of disabled people’s health matters both worldwide and within Senegal.3 Within Senegal, innumerable international and national organisations and actors are working to strengthen Senegal’s health and health education systems, making it a pertinent issue for further exploration.

Disabilities in Senegal

According to the last census in Senegal in 2013, around 5.9% of the population has a disability of some type.4 The rates of disability for women are higher than for men, particularly in urban areas, such as Dakar, the capital city, where 6.3% of women and 5.3% of men have a disability of some type. The most common disabilities are vision-related (2.1%) and motor-related (1.9%).

Disability rights laws

Citizens with disabilities have specific rights and protections under Senegalese law, as stated in the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.5 In 2010, the National Assembly of Senegal enacted a Social Orientation law that aims “to guarantee equal opportunities for disabled people as well as the promotion and protection of their rights against all forms of discrimination” (p.4).5 Various other Senegalese laws and decrees guarantee disabled people the right to an education, mandate that existing and new infrastructure follow international accessibility criteria, prohibit job discrimination, and state that health care establishments must be physically accessible for disabled people.5 Yet, despite these laws and protections, disabled people are more likely to be unemployed, have poor access to education and public buildings, and live in impoverished conditions compared to non-disabled people.5 Health facilities with disability accommodations are rare, and health care remains costly.6

Perhaps one of the most well-known initiatives for improving disabled people’s quality of life in Senegal is the “carte d’égalité des chances”, established through the Social Orientation law. All people who have disabilities are eligible to receive this card, which entitles the owner to monetary benefits, free or subsidised transportation, full or partial coverage of public health services and a reduction of health care costs in private health care structures, although there is no specific information on the exact health services that are included or excluded from coverage by the card.7 Because the law does not mention any services that are excluded, it is assumed that SRH services are also covered by the card. Despite the creation of this card, studies show that the card is either not available to all disabled people or “has had no impact on their access to health services” (p.10),8 and that the cards cannot yet be used for discounted transportation or education, according to the Senegalese Federation of Disabled People’s Associations (FSAPH).8 As a result, the cards are not benefiting disabled people as intended. Currently, people can apply for the carte d’égalité des chances by going to either the SDAS (Departmental Service of Social Action) or the CPRS (Center of Social Promotion and Reintegration). There are currently four SDASs in the region of Dakar (one in each department). Although there should be one CPRS per commune, the Ministry of Health and Social Action states that actual coverage is around 11.5%, revealing a significant gap to be filled.9

Disabilities and sexual and reproductive health

Previous research on sexual and reproductive health (SRH) for disabled people in Senegal has revealed inequities, discrimination, and low levels of access to services and information. Young Senegalese participants with disabilities in a qualitative study reported low knowledge of, and difficulties accessing, SRH services including contraception and gynaecological consultations, despite a clear need for them, and spoke of being stigmatised and marginalised.7

There exist few statistics on SRH service needs among disabled women in Senegal, but among women aged 15-49 in general, 14% of married and 49% of unmarried but sexually active women have unmet needs for contraception, and only 30% of women have complete knowledge on HIV/AIDS, compared to 40% of men.10 Women are 1.6 times more likely than men to contract HIV; among disabled people specifically, HIV prevalence is almost two times higher for disabled women than for disabled men (2.5% versus 1.3%).11,12

Disabled women in particular are marginalised both by their disability and their gender, presenting unique challenges for their health care. This is understood through the sociological concept of intersectionality, coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw, which is the intersection of different social categorisations, marginalisations, and discrimination for populations or individuals.7 These women also face a double stigmatisation related to their sexual health and their disability, as sex in general, particularly pre-marital sex, can be taboo in Senegal, and disabled people face the stereotype that they are not sexually active.13 These stigmas and taboos can cause people to be hesitant to discuss SRH issues and seek care, thus reducing access to and use of SRH services.14 Additionally, health care workers’ knowledge of and response to the health and sexuality needs of women with disabilities has been found to be often insufficient.15

It is evident that people with disabilities, and particularly women with disabilities, are a marginalised and stigmatised population in Senegal and are confronted with significant challenges in their sexual and reproductive health. There remain significant gaps in research on the state of access to SRH services and information for these women. Research on this topic can provide evidence for those who aim to create policies and programmes that shape health care for disabled women in Senegal.

This study aims to:

increase understanding of the experiences that Senegalese women with physical motor disabilities have when accessing SRH services and information;

examine the attitudes and opinions that these women have toward the accessibility of SRH care services and information;

identify where these women access SRH information, who or what they rely on for quality information, and how well-informed they feel regarding SRH topics; and

highlight their suggestions for improving access to and the quality of these services and information.

Methodology

The researchers carried out this study from October to December 2019 in the region of Dakar in Senegal, which includes the four departments of Dakar, Guédiawaye, Pikine, and Rufisque. The researchers used a semi-structured interview protocol containing 46 closed and 30 open-ended questions and conducted a total of 31 in-depth interviews throughout all four departments. A mix of closed and open-ended questions was used to encourage rich and diverse perspectives while also allowing for the identification of sample demographics. Participants from outside of the Dakar region were not considered for this study due to time constraints. In order to be eligible to participate, respondents had to identify as a woman, be aged between 20 and 30, have a physical motor disability, and consent to being interviewed. Other researchers, disability activists, and public health actors in Senegal suggested a younger population would be particularly pertinent for research. Researchers initially selected an age criterion of 20-24 years old to narrow the participant pool, but due to difficulties in finding participants within this age range, extended the age limit to 30 years old. Physical motor disabilities were chosen as the primary criterion as they are one of the two most common types of disability in Senegal. They were defined as a disability causing “the partial or total loss of function of a body part, usually a limb or limbs” (p.1).16 Women with disability types other than physical motor disabilities were excluded in order to produce results specific to women with physical motor disabilities. Further, women with other disability types may have different experiences and challenges in accessing SRH services and information which may have different programmatic and policy implications. Examining these experiences as well would have exceeded the scope of this manuscript. The SRH services examined in this study were defined as medical services providing care and consultation for STIs, contraception, maternal care, and other issues or illnesses related to the reproductive organs. Initial participants were recruited with the help of a local disability association, who called women and informed them of the study before we contacted them directly. Working directly with disability associations also ensured a community-based participatory approach to this study, meaning that the study’s components, including seeking participants and designing the interview protocol, were the result of collaboration with these associations. Participants received a consent form, and we explained the objectives and potential risks and benefits of the study, after which they chose whether or not to participate. The snowball sampling method was used from thereon, with some participants being recruited with the aid of previous participants, other disability associations, public health workers, and disability activists throughout Dakar. The researchers travelled to each participant to meet them at their residence or local disability association and conducted all interviews in a private location. Each interview took about thirty minutes and was conducted in either French or Wolof depending on the wishes of the participant (both researchers speak Wolof fluently). All interviews were recorded using a voice recorder and then loaded onto the principal investigator’s computer which is password-protected.

Data analysis

All interviews were transcribed verbatim and interviews that were conducted in Wolof were translated into French by the co-researcher, who is Senegalese. The interview transcripts were then loaded onto NVivo qualitative data analysis software and analysed by the principal researcher using thematic analysis. “Nodes,” similar to labels, were created by going through each interview and highlighting significant segments of text. For example, every time a participant spoke about feeling judged for her disability, the relevant section was highlighted and saved under the node “disability judgement.” This was repeated for all interviews. The principal investigator then went through all nodes to identify themes that overlapped, consolidating material where appropriate and grouping themes together under larger, overarching themes that emerged from the data. Quotes from different participants were selected to demonstrate these themes and provide a narrative. Excel was used to compute basic frequencies and proportions for responses of interest, from which tables and histograms were created.

Ethical considerations

Ethics approval was obtained from the National Ethics Committee for Health Research (CNERS) located at the Ministry of Health and Social Action in Dakar (Approval Date: 23 September 2019, Approval Number 00169) as well as from the University of Missouri-St. Louis’ Institutional Review Board (IRB) (Approval Date: 12 October 2019, Application Number: 1507192-1) before research began. The researchers also formed partnerships with multiple disability associations throughout Dakar to recruit study participants. The associations guided the researchers in learning more about disabilities in Senegal, how to be sensitive to and mindful of the diverse experiences that participants have had, how to build trust with participants, and how to ask the most appropriate questions during interviews. All participants signed consent forms before the interviews began, and researchers made sure that all participants fully understood the scope of the study, the potential risks and benefits, and the autonomy that they had whether or not to participate and to stop the interview at any time with no repercussions.

Results

Sample overview

In total, 31 participants were interviewed. One woman who was approached declined to participate after review of the consent form. Table 1 provides a breakdown of ages of participants, their geographical locations, their employment status, their highest level of education, and whether they use support equipment such as a wheelchair or cane.

Table 1.

Distribution of participants’ geographic locations, ages, employment and education, and use of technical equipment such as wheelchairs or canes (n = 31)

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Location | ||

| Dakar | 22 | 70.9 |

| Guédiawaye | 4 | 12.9 |

| Pikine | 3 | 9.7 |

| Rufisque | 2 | 6.5 |

| Age | ||

| 20–24 | 15 | 48.4 |

| 25–30 | 16 | 51.6 |

| Paid employment status | ||

| Currently employed | 2 | 6.5 |

| Unemployed | 29 | 93.5 |

| Highest level of education completed | ||

| None | 5 | 16.1 |

| Primary school | 8 | 25.8 |

| Secondary school | 6 | 19.4 |

| Higher education | 12 | 38.7 |

| Use of technical equipment such as a cane or wheelchair | ||

| No | 16 | 51.6 |

| Sometimes | 1 | 3.2 |

| Yes | 14 | 45.2 |

Of the 31 women interviewed, 16 had ever visited a health care establishment to seek SRH services or information, and 11 reported having had sexual intercourse. All of the women who reported having had sexual intercourse had also sought out SRH services or information.

Access to sexual and reproductive health services and information

Overall, 16 of the 31 women interviewed stated that the SRH services in Dakar are not physically accessible to them and 12 stated that they are physically accessible. One woman did not know if services were accessible or not, one woman felt that services were somewhat accessible, and one woman did not respond. Out of the 16 women who had ever sought out SRH services or information, 11 said that their disability affects the way in which they access these services and information. Sixteen women said that SRH information is not accessible to them, 14 stated that the information is accessible, and one woman did not know. Most women felt that accessing SRH information was easier than accessing SRH services. The interviews uncovered five key themes that emerged as core barriers in accessing SRH services and information:

- structural barriers within health facilities

- financial barriers

- long wait times

- transportation difficulties and health facility distances

- health providers’ attitudes/lack of orientation

These are discussed in more detail below.

Structural barriers within health care facilities

One of the most common barriers cited to accessing SRH services was a lack of wheelchair ramps and elevators. Participants described having significant difficulties getting into health facilities and then making it to consultation rooms. They described consultation tables as being inaccessible, explaining that “sometimes, when you go up [on to the table], you fall” (P11). One woman explained that pregnant disabled women have significant difficulties getting onto hospital beds to give birth. Another woman explained that “when you are disabled, [medical professionals] barely help you, it’s only your guide who helps you” within health facilities (P9). Another woman expressed feeling disregarded at health facilities, saying that “there is no one to help me. There is one person over there who I exhaust often. Every day, he’s the one who helps me when I go into the hospital” (P27). Navigating hospitals with no ramps and going up stairs was noted overall as one of the biggest structural impediments. On the other hand, a couple of women stated that they have found hospitals with ramps, and that they were pleased with these facilities’ accessibility.

Financial barriers

Many women spoke of having difficulties paying for consultations within health facilities. Although the carte d’égalité des chances is supposed to provide a reduction in the cost of services, the cards are not accepted by all health establishments, and some women have not yet received their cards, telling stories of some people waiting years before finally getting them. Two women spoke of their cards not being accepted at Dantec Hospital and Philippe Senghor Hospital, two major public hospitals in Dakar. One woman recounted her financial difficulties in accessing SRH services, explaining that during her last consultation,

“[the doctor] told me that it’s possible I’m pregnant. And that I should do an ultrasound. But you know, it’s hard to find money to go do an ultrasound, that’s why I haven’t yet gone to my appointment. And also, since then I haven’t had my period. But as soon as I have money I’ll go to the ultrasound” (P11).

One woman explained that both she and her husband travel downtown to ask for money on the streets. If they don’t have enough money, she cannot get the medical care she needs, and at one point was unable to seek follow-up care after surgery because she did not have the money. Another woman explained that she has never sought out SRH care services because of a “lack of money.” Indeed, 29 participants do not currently have a paying job, and most are financially supported by their parents or by other family members. Several women spoke of the inevitable refusals if they were to seek jobs because of discrimination against their disabilities. As one woman put it,

“Not all workplaces hire disabled people. There are certain ones, when you go to search for a job, they disregard you because of your disability. You can be capable of doing the work, but they won’t hire you because they see your disability and say to themselves ‘Ah, if we hire her too, her work will not be normal,’ for example” (P19).

One woman explained that Humanité & Inclusion, an international NGO that supports vulnerable populations, supports her financially by paying for her transportation and for trainings each month that teach technical skills.

Long wait times

Long wait times in health facilities were cited many times by participants as being exceedingly difficult and exhausting, making it hard to access SRH services. Participants told of waiting more than three hours and even entire days to see doctors. As one woman explained,

“I wake up very early, you have to wake up at 5 in the morning because … if you don’t leave early, if you arrive late, they will not see you. I’ve gone twice and they didn’t consult me because I arrived late, so I went back home” (P19).

Many women expressed the desire to be given priority over non-disabled patients waiting at health facilities. Even when certain participants expressed satisfaction with the level of accessibility of SRH services, some of them still noted that the wait time in health facilities is difficult and could be improved.

Transportation difficulties and health facility distances

Participants described health facilities as being too far away and recounted difficulties when trying to access public transportation. One woman said that she faces discrimination when using public transportation and that it is expensive to go to the hospital because it costs around 5000 CFA (US$ 8.51). Multiple women expressed that transportation is expensive because the hospitals are so far away from where they live. On the other hand, others said that health care facilities were nearby, and some women even noted that there were accessible health facilities on their university campus. One woman described a discriminatory experience she faced when using public transportation:

“If you get on the bus, they make you get off, saying that your wheelchair doesn’t have a place on the bus. I remember when I was at full-term pregnancy, going to the hospital for an appointment, they made me get off the bus. That day I cried, asking myself why they made me get off while the able-bodied people get to continue. My appointment was approaching, I was supposed to be there at noon. It was difficult … I had to wait for another bus” (P11).

Other women expressed difficulties trying to obtain public transportation as well – as one woman put it, “when I stop a means of transport, they rarely accept because they think of the time it will take them so that I can get onto the bus” (P30).

Health providers’ attitudes and lack of orientation

Many women expressed disappointment in “l’accueil” (French) or “teertu bi” (Wolof) at health care facilities, which directly translate to “the welcome,” understood as the manner of welcoming one into an establishment or a home. The welcome can also encapsulate various aspects of one’s experience in a health care facility, from the orientation when one arrives – i.e. the signs that indicate where different services within a health facility are located – to the way that the doctor speaks to patients and interacts with them. In terms of orientation within health facilities, many women expressed that it is difficult to know where to go to buy a ticket† to see the doctor; secretaries and other workers within the hospital are not helpful and orientation signs are not clear. Once women arrive to see the doctor, midwife, or gynaecologist, they speak of having poor experiences because of health professionals’ attitudes and behaviours. According to one participant,

“If you come asking [for SRH information], especially if you have a certain age, [medical professionals], in their minds, they will look at you with a certain look, they have the tendency to judge you, even though they should give you information. For me, this is maybe why I have not gone” (P2).

Other women spoke of this issue too, and noted that it is difficult to seek out SRH information and services when you are not married:

“If you go to see the midwife to ask her about things concerning birth control, automatically she will have reservations and ask you if you are married or not. As soon as you tell her that no, you are not married, she will look at you in a poor way and judge you” (P21).

This fear of being judged for seeking SRH information was a common theme and is related both to the cultural taboos of sexuality and sex before marriage as well as to being disabled, as several women stated that they feel judged by medical professionals when seeking SRH information specifically because of their disability. As one woman said,

“There are people, when you approach them to get information and you are not married like me, they refuse to give you the correct information and to tell you everything, even though in my opinion as soon as a girl begins to have her period, she should be informed” (P21).

Another woman expressed it being difficult to obtain SRH information because people with disabilities are ignored in society, “whether that be in the hospitals, in establishments, in the social life” (P24).

Other women told of being rushed by medical professionals, and not being listened to because staff are “hurried” and there “are too many sick people” (P32). Another woman described an experience she had where the medical professional consulting her said “hurry up, you’re slow, I’m in a hurry,” while she was hoisting herself up onto the consultation table, something which takes longer for her than for non-disabled women (P11). Participants described midwives belittling them, and several spoke of pregnant women being disrespected and mistreated by midwives while giving birth. Several women also spoke of there not being enough medical professionals in hospitals.

Knowledge of and sources of SRH information

Overall, most women (61%) reported not feeling well-informed on sexuality, contraception, and sexual and reproductive organs; 23% of women felt somewhat informed, and 16% felt well-informed.

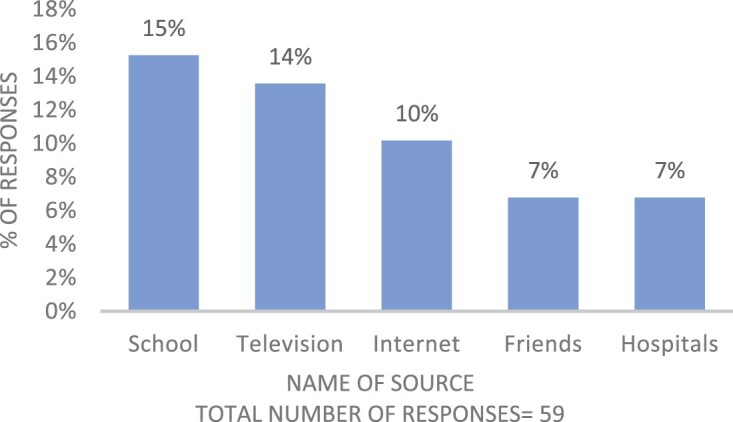

Participants were asked what sources they used to access information on contraception, sexuality, and sexual and reproductive organs. The five most commonly cited sources were school, television, internet, friends, and hospitals (Figure 1). Several women noted campaigns and informational sessions hosted by non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and disability associations as being highly instructive on SRH matters. Marie Stopes International (an international NGO), Taxaw Jigeen (a Senegalese NGO), and various local disability associations in Dakar were noted as being important sources of information. Bajenu gox (a Wolof phrase translating directly to “neighborhood aunt”) were also cited by various participants as playing a key role in educating women on SRH topics. Bajenu gox are women leaders designated by communities to act as community health care workers, and they are particularly involved in promoting women’s health throughout Senegal. They are considered by community members to have a good reputation and do crucial work that maintains well-being in families.17

Figure 1.

The top 5 most common sources of information on sexuality, contraception, and sexual & reproductive organs

Participants listed multiple sources in their responses. Only the five most recurrent sources are shown in this figure. The other 47% of responses were varied and included “radio” and “family members” as responses.

When asked to cite their most reliable sources of information on sexuality, contraception, and sexual and reproductive organs, respondents’ top five responses were midwives, doctors, gynecologists, hospitals and the internet information (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The top five most reliable sources for obtaining information on sexuality, contraception, and sexual & reproductive organs

* Participants listed multiple sources in their responses. Only the five most recurrent sources are shown in this figure. The other 40% of responses were varied and included “friends” and “television” as responses.

Seventy-one per cent of women said that they do not feel generally well-informed regarding STIs and only 10% said that they do feel well-informed, while 16% feel “somewhat” informed. One woman did not respond.

Regarding contraceptive methods, more than 75% of participants knew at least three different types of contraceptive methods, the most commonly cited ones being contraceptive pills, condoms, and the intrauterine device (IUD). Out of the 31 participants, 87% reported having never used contraception, while 13% said they had. The top five most common sources of information on HIV/AIDS were school, television, media, the radio, and undefined sources‡ (Figure 3). The majority (77%) of participants did not know of any other STI other than HIV; among those who did, only two participants knew of at least two and could properly name them.

Figure 3.

The top five most common sources of information on HIV/AIDS

* Participants listed multiple sources in their responses. Only the five most recurrent sources are shown in this figure. The other 38% of responses were varied and included “friends” and “hospitals” as responses.

At the time of the study, 84% of participants had attended or were attending school. Of these, 82% believed that there are not enough school courses on SRH subjects. Almost all participants who had attended school reported that they had taken at least one course that discussed SRH, and most cited school as one of their top five sources of SRH information.

One woman stated that her disability prevented her from going to school sometimes, and another woman explained that she was turned away from registering at a particular school because she uses a wheelchair and the school could not accommodate her. Another woman said that her disability is what caused her to stop school at the elementary level. Others described difficulties adapting to school because of their disabilities and the fact that school was mostly comprised of non-disabled students. One woman told of students in her class bullying her for excelling, saying that they couldn’t let a disabled person do better than them in class. There are only a handful of schools in Dakar that are specifically dedicated to students with disabilities. Several public schools in Dakar are currently trying to integrate students with disabilities into schools with non-disabled students while providing them specialised tools they need to succeed.8

The carte d’égalité des chances: concerns and barriers

Fifty per cent of participants did not use the carte d’égalité des chances because they did not currently possess one, but all of the women except one (who was not asked) expressed that they would like to use the card. One of the most common complaints from participants was that their card had not yet been distributed to them. Many participants explained that they had been waiting for two years or more, yet each time they checked to see if the card was ready, they were told that their card is not available or that their names are “not registered on the lists.” Many participants told stories of presenting their cards in hospitals and not receiving deductions in medical care costs. Others explained that they had received information that the card would help them obtain a job, yet they have not seen this benefit. One woman said that “there are others who even have the card and don’t even see the [trimonthly sum of money]§ nor the free transportation ticket, and so for those people, the card is no use” (P23). She also explained that within the disability association that she is a member of, there are disabled people who don’t know where to sign up for the card, and who have applied for the card but have never received it. Some women, on the other hand, told of going to hospitals to receive medical care, being asked to present their cards, and receiving deductions of up to 50% in the cost of treatment. A majority of participants expressed wanting to see an increase in the trimonthly payments, as well as quicker turnaround times in receiving the card after sign-up. A majority would like to see the card cover more transportation and medical costs.

Respondents’ recommendations to improve SRH services and information in Dakar

Participants offered a number of recommendations to improve SRH services and information in Dakar. One participant suggested that health care establishments should “properly welcome people when they arrive [and not] judge people differently just because someone has a disability and another person does not” (P18). Another participant explained that:

“There are people that go to the hospital and [health care providers] don’t welcome them like they should. They throw them to the side or yell at them. For people who are pregnant, they mistreat them. We must reinforce the capacities of [health care providers]” (P28).

Two women offered suggestions for improving the accessibility of the carte d’égalité des chances:

“[The people who manage the carte d’égalité des chances] can go to the field again and conduct surveys because there are people who cannot and who do not know where they can go to get the card, but if the [carte d’égalité des chances] people themselves, they come to us, they can explain it to us. Because there are a lot of people who believe that we all have our cards, but this is not the case” (P7).

Another participant explained that:

“There are disabled people who want to go [get the card] but moving about is not easy, so each neighborhood should have a location where one can apply for the carte d’égalité des chances. Once the card is ready, they’ll let you know that this is where you can claim the card. If they do this, it will be easier for disabled people” (P1).

One woman expressed wanting “health care establishments to come to us, we the disabled, because we need it, because there are disabled people who are here, but they don’t know [about SRH information]” (P7). Another spoke of technology’s role in SRH, explaining, “seeing as young people use social media, [public health actors] could create applications to raise awareness about reproductive health” (P1). Commenting on the wait times, accessibility, and transportation, a respondent suggested that health care establishments:

“give a larger priority to people with disabilities. The wait is long for us when we go to consultations, and it’s not easy to access health care facilities without ramps. [Health care or government actors] need to facilitate transportation for us” (P12).

On the topic of health care providers’ interactions with disabled women, one woman said that they should “not preoccupy themselves with who is married or not, who is single or not. I believe that every woman who goes to a health care facility, she is in need of and wants to have reliable information” (P21). To reduce prejudices and biases from SRH providers, one woman suggested that:

“to avoid certain prejudices … like at church you see someone who is talking with the priest but you don’t see him, [health care workers] could do something like that too, you know like you come and sit, the person who responds to your questions will not know that it’s you who has come here” (P2).

Another woman spoke of SRH education in schools, saying, “I think that courses [on SRH] should be expanded because I only took them in middle school” (P17).

Discussion

Very few studies have been conducted on disabled women’s access to SRH services in Senegal. This study responds to this research gap by providing targeted insights on the experiences of women with physical motor disabilities in the region of Dakar. Interventions that may be developed from this research will benefit from having evidence that is specific to this population.

Overall, results show that participants experienced significant barriers to accessing SRH services and information. Physical inaccessibility within health centres was cited numerous times as being a major barrier. Many participants spoke of financial difficulties as limiting access as well. This is also a barrier for women in the general population: a 2017 study revealed that 45% of women ages 15–49 face financial barriers to accessing health care services.10 It may be notable that all but two participants were unemployed at the time of the study. The reasons behind the high unemployment rate among participants were not deeply probed, but participants’ stories suggest that societal discrimination against their disabilities may impact their ability to find work. Thus, even though both disabled and non-disabled women face financial barriers in accessing health care, these difficulties may be greater for disabled women who face greater hurdles in obtaining employment and are more likely to be unemployed. Financial barriers to accessing SRH services could be lessened by ensuring that all people with disabilities have the carte d’égalité des chances and know where the card will be accepted. Greater attention could be given to ensuring that people with disabilities have equal access to work in Senegal, and businesses could implement more inclusive hiring practices.

Participants reported feeling judged by health care professionals both because of taboos surrounding sex and because of their disability. Senegalese disabled participants in a 2017 study also noted that health care providers “make you feel your disability,” (p. 8) marginalise disabled people, and neglect disabled patients because of their disabilities.7 In another 2017 study of people with disabilities and their health care access in Saint Louis, Senegal, 35% of participants reported having negative interactions with health care professionals, who they felt were insensitive to their needs. Health providers interviewed in this study noted that some of their staff “lacked awareness or experience handling people with disabilities” (p. 7).18 Although judgement surrounding premarital sex also applies to non-disabled women, this judgement, coupled with stereotypes surrounding the sexuality of disabled people, creates a double stigmatisation that disabled women confront when accessing SRH services and information. Ideally, health professionals could receive training in remaining unbiased and non-judgmental in their work with disabled patients and unmarried patients (it is not clear whether or not health care professionals in Senegal are currently trained in working with patients with disabilities).

Poor orientation within health care structures was noted as a barrier by participants and seems to be experienced by the general population in Senegal as well. In a 2016 study conducted in ten regions of Senegal including the Dakar region, only 33% of health care establishments observed had proper orientation signs with images.19 In a separate study on health care accessibility in the regions of Dakar and Kaolack, researchers found that a lack of orientation in the emergency department as well as absence of personnel and communication difficulties between personnel and patients created large obstacles to accessing care.20 Although both disabled patients and non-disabled patients can experience poor orientation and treatment from health personnel, these experiences may be more difficult for disabled women. They may spend extra time locating the department or provider they are seeking care from because of structural inaccessibility coupled with poor orientation. Strengthening the orientation within health care structures in Senegal will be pertinent not only for the health care experiences of disabled people but also for the general population.

Long wait times in public hospitals and other public health facilities in Senegal are widespread and may not be specific to women with disabilities. One potential reason for long wait times could be shortages in health care professionals. Throughout the entire country, there were only 0.1 physicians to 1000 people and 0.3 nurses and midwives to 1000 people in 2017.21 Further research to determine whether disabled people wait longer than non-disabled people would be pertinent. Waiting for an extended period may be more challenging for those with disabilities because of structural inaccessibility within health establishments. If the waiting area cannot accommodate a wheelchair, or if bathrooms are inaccessible, for example, patients with disabilities may experience more discomfort than non-disabled patients. Disabled participants in the Senghor et al study18 also spoke of long wait times, and some noted that they were not given priority, despite having the carte d’égalité des chances. It is unknown whether or not the carte d’égalité des chances allows disabled patients to be seen first, but if not, this could be standardised throughout the country. Health care facilities specifically dedicated to treating disabled people could be created as a way to give people with disabilities their own space that is adapted to their needs.

Many participants described the long distances to health care establishments as a barrier to accessing SRH services and information. A geographical study examining health care establishment distribution in the region of Dakar found that establishments become sparser in the eastern region (toward Guédiawaye, Pikine, and Rufisque) and away from major towns, and are mostly concentrated in the Dakar department.22 It is possible that the participants in this study who spoke of long distances to reach SRH services live in areas of the Dakar region where health establishments offering these services are less available. Future research that examines the relationship between participants’ access to SRH services and their geographical distance to health establishments could help identify areas where access to these services is lacking. Participants also spoke of difficulties taking public transportation, illuminating the need for more accessible public transportation that can accommodate wheelchairs and other technical equipment that people with disabilities may use.

In general, participants showed low levels of knowledge of STIs, and most participants reported not feeling knowledgeable on various SRH topics such as STIs, contraception, sexuality, and sexual and reproductive organs. Every participant had heard of HIV/AIDS, which is comparable to the general population, in which 96% of women had heard of HIV/AIDS.10 Low levels of knowledge confidence may be due to the barriers revealed through participant interviews and discussed above that make it difficult to access services to obtain information on SRH. Despite a majority reporting not feeling knowledgeable on these topics, more than 75% knew of at least three types of contraception. These results are also comparable to the general population, as 90% of Senegalese people know of at least one type of contraception.10 Women’s most common sources of information on contraception were the radio and television.10 This is similar to the common sources that the women in our study listed, as television was the second most cited source for information on sexuality, contraception, and sexual and reproductive organs and radio was one of the top five most common sources for information on HIV/AIDS. Increasing the dissemination of messages on SRH topics through television and the radio may increase not only disabled women’s knowledge but the general population’s knowledge as well.

A lack of quality instruction on SRH topics could be a factor in the low levels of knowledge confidence that were reported. While school was cited as the most common source for learning about contraception, sexuality, and sexual and reproductive organs, most of the participants stated that there are not enough SRH-related classes in school. Deeper research into the relationship between SRH education in schools and SRH knowledge among disabled women is necessary. Investigating the SRH curriculum that is currently taught in schools and identifying content that addresses disabilities would be particularly valuable. Various women spoke of difficulties attending school because of their disability. Structural accommodations in schools such as wheelchair ramps and adapted bathrooms for disabled people are not widely available and there exist no constitutional clauses that prohibit schools from turning away disabled students or that require them to adequately accommodate disabled students.8 Future research on this subject could look at the relationship between levels of knowledge on SRH matters for disabled women and their school attendance, and the factors affecting school attendance.

Disabled women’s access to SRH services and information can only be improved by taking into account the perspectives of people with disabilities and directly involving them in decision-making processes. The Senegalese Federation of Disabled People’s Associations’ report highlights the current state of disabled people’s rights and social inclusion in Senegalese society and offers numerous suggestions for improving education, job inclusion, and health care for disabled people (with a particular focus on women as well), among other areas.8 This source could be beneficial for actors looking for concrete ways to make improvements in key areas.

One of the strengths of this study was that the researchers worked directly with local disability associations to recruit participants; this helped to build trust between the researchers and the participants as participants were able to reach out to their associations with questions or concerns. A limitation was that the researchers faced hurdles in gathering participants, which limited the sample size to 31 participants instead of the 40 initially planned. Despite this, the sample included a large range of ages, although it lacked variety in the geographical distribution of participants. Given that 16 out of the 31 women interviewed had ever sought SRH information or services, some responses from participants may have been based on perceptions, or stories that they may have heard from others, and not on direct experiences. Due to time and budget constraints, the researchers did not interview health providers or government officials; these perspectives should be included in future research to gain a comprehensive understanding of the shortcomings in provision of SRH services and information. Another limitation was the fact that one of the researchers is not Senegalese and the fact that neither of the researchers have any physical disabilities. This could have lessened the amount of trust between the researchers and participants, thus affecting the amount of information participants were willing to share. However, both researchers speak Wolof and French fluently and thus were able to spend time building rapport with participants before beginning interviews, and in most cases, also spent time speaking with participants’ families, as most women lived with their families.

Conclusion

Based on the results of this study, the recommendations from participants, and recommendations from disability associations in Senegal, we propose three key steps for improving access to SRH services for disabled women and people in general. First, it is important to strengthen and implement standardised training for health care workers on working with patients with disabilities. For professionals who work in sexual and reproductive health, training should address implicit biases that they may hold toward disabled people and their sexuality. Training should also reinforce the importance of providing sexual and reproductive health care to everyone, regardless of marital status, gender, age, disability, or any marginalised identity, and regardless of providers’ personal beliefs. Second, the distribution of the carte d’égalité des chances should be scaled up, and clearer documentation on the exact services that are covered by the card should be produced. Making sure that people with disabilities know where to apply for and receive the card or other programmes for subsidising the cost of health services is crucial. Interviewing the directors of health establishments and government officials in charge of the carte d’égalité des chances is necessary to gain clearer understanding of the program. Finally, implementation of and continuous follow-up on accessibility standards in all health care establishments is crucial. As one participant perfectly summarised, “[people need] to change infrastructures and adapt them to people with disabilities to better facilitate our access to hospitals. And especially better respect us as patients within these services” (P8).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank and express deep gratitude first and foremost to all of the participants in this study for welcoming us into their homes, sharing their stories with us, teaching us about disabilities and health care in Senegal, and agreeing to have their stories published and shared with others. We hope that we have honoured your voices and stories in the most accurate way possible. We also wish to sincerely thank and express deep gratitude and appreciation to the following people who contributed to this research and guided, supported, and helped us throughout the study: Dr. Larry Irons, Associate Teaching Professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of Missouri-St. Louis; Salif Camara, Coordinator, Field Researcher at Global Research and Advocacy Group; Khadim Talla, President of the Association Handicap.sn; Kiné Ndiaye, Social Worker, Special Education Teacher, and Coordinator of Special Education at the Fédération Sénégalaise Des Associations De Personnes Handicapées; Fatou Khady Ba, President of the Women’s Committee in the Fédération Sénégalaise Des Associations De Personnes Handicapées; Virginie Marie Odile Kantoussan, Coordinator for the Health Department at Africa Consultants International; Ndeye Dagua Dieye; Amadou Moreau, Founder and Vice President of Global Initiatives at Global Research and Advocacy Group; Moustapha Dieng, Technical Advisor, HIV, for the Conseil National de Lutte Contre le SIDA; and Arama Samba, member of the Association des Handicapés Moteurs in Yoff. Your various contributions were numerous and invaluable – without your input, guidance, instruction, and support, we could not have done this important research.

Footnotes

In many Senegalese public health establishments, patients must pay a fee and receive a ticket before seeing a doctor or other medical professional if they do not have an appointment.

Sources that were not clearly defined by participants. For example, several participants responded that they had heard of HIV/AIDS but were not sure where they had heard of it, or that they had heard of it on the street.

This sum of money refers to the “Programme National de Bourses de Sécurité Familiale,” a social aid program designed to provide 300,000 impoverished and vulnerable Senegalese families with 25,000 FCFA ($46.69 USD) every 3 months.23

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- 1.Cohen SA. The broad benefits of investing in sexual and reproductive health. Guttmacher Rep Public Policy. 2004;7(1):5–8. Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2004/03/broad-benefits-investing-sexual-and-reproductive-health#. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mac-Seing M, Zarowsky C.. Une méta-synthèse sur le genre, le handicap et la santé reproductive en afrique subsaharienne. Santé Publique. 2018;29(6):909–919. doi: 10.3917/spub.176.0909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs . Disability and development report: realizing the sustainable development goals by, for and with persons with disabilities. 2018. Available from: https://social.un.org/publications/UN-Flagship-Report-Disability-Final.pdf.

- 4.Agence Nationale de la Statistique et de la Démographie (ANSD) . Rapport Definitif: Recensement Général de la Population et de l’Habitat, de l’Agriculture et de l’Elevage (RGPHAE). 2014. Available from: https://www.ansd.sn/ressources/rapports/Rapport-definitif-RGPHAE2013.pdf.

- 5.Handicap International . Guide de poche sur la législation du handicap au Sénégal. 2010. Available from: https://www.societeinclusive.org/images/pdf_files/Afrique/Guide_legislation_senegal_broch.pdf.

- 6.Thiam A, Sy Sow SA.. Sénégal. Afr Disability Rts YB. 2016;4. Available from: https://upjournals.up.ac.za/index.php/adry/article/view/488. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Journal Officiel de la Republique du Sénégal . Loi d’orientation sociale n° 2010-15 du 6 juillet 2010. 2010. Available from: http://www.jo.gouv.sn/spip.php?article8267.

- 8.Burke E, Kébé F, Flink I, et al. . A qualitative study to explore the barriers and enablers for young people with disabilities to access sexual and reproductive health services in Senegal. Reprod Health Matters. 2017;25(50):43–54. DOI: 10.1080/09688080.2017.1329607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fédération Sénégalaise Des Associations De Personnes Handicapées . Rapport Complémentaire Au Rapport Initial Du Sénégal Sur La Mise En Œuvre De La Convention Relative Aux Droits Des Personnes Handicapées. 2019. Available from: https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CRPD/Shared%20Documents/SEN/INT_CRPD_CSS_SEN_33931_F.docx.

- 10.Ministère de la Santé et de l’Action Sociale . Plan National de Développement Sanitaire et Social (PNDSS) 2019–2028. 2019. Available from: https://www.sante.gouv.sn/sites/default/files/1%20MSAS%20PNDSS%202019%202028%20Version%20Finale.pdf.

- 11.Agence Nationale de la Statistique et de la Démographie (ANSD) [Sénégal] and ICF . Sénégal: Enquête Démographique et de Santé Continue (EDS-Continue 2017). 2018. Available from: http://www.ansd.sn/ressources/rapports/Rapport%20Final%20EDS%202017.pdf.

- 12.Conseil National de Lutte Contre le SIDA . Enquête Nationale De Surveillance Combinée Des IST Et Du VIH/SIDA: ENSC 2015. 2017. Available from: https://www.cnls-senegal.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/RAPPORT-DE-SYNTHESE-ENSC-2015-1.pdf.

- 13.Conseil National de Lutte Contre le SIDA . Rapport Annuel 2016. 2017. Available from: http://www.cnls-senegal.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/rapport-annuel-2016-1.pdf.

- 14.World Health Organization, United Nations Population Fund . Promoting sexual and reproductive health for persons with disabilities: WHO/UNFPA guidance note. World Health Organization; 2009. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44207.

- 15.Griffin S. Literature review on Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights: universal access to services, focussing on East and Southern Africa and South Asia. United Kingdom Department for International Development; 2006. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08c2940f0b64974001036/LitReview.pdf.

- 16.Diatta Sagna M. Le vécu social des femmes avec des limitations fonctionnelles et porteuses du VIH/sida au sénégal [Master’s thesis]. Université de Sherbrooke; 2013. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/11143/6505.

- 17.Henderson JM. Motor impairment. International Neuromodulation Society; 2012. Available from: https://www.neuromodulation.com/motor-impairment.

- 18.Diop RA, Kébe GF, Sarr SC, et al. . The Bajenu Gox as social mobilization and social norms transformation agents in maternal, child and youth health in Senegal. Afr J Reprod Health. 2021;25(3s). Available from: https://www.ajrh.info/index.php/ajrh/article/view/2806/pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Senghor DB, Diop O, Sombié I.. Analysis of the impact of healthcare support initiatives for physically disabled people on their access to care in the city of Saint-Louis, Senegal. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(S2). doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2644-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.L’Institut Panafricain pour la Citoyenneté, les Consommateurs et Développement (CICODEV AFRIQUE) & OSIWA . Accueil dans les structures de santé: Présentation des résultats. 2016. Available from: http://www.cicodev.org/cloud/ACCUEIL-VF_Presentation-resultats120516.pdf.

- 21.Gueye AK, Seck PS. Etude de l’accessibilité des populations aux soins hospitaliers au Sénégal. Groupe Thématique Santé. 2009. Available from: https://www.plateforme-ane.sn/IMG/pdf/etude_accessibilit_des_populations_aux_soins_hospitaliers_au_s_n_gal.pdf.

- 22.The World Bank . Physicians (per 1,000 people) – Senegal. The World Bank: Data; 2017. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.MED.PHYS.ZS?locations=SN.

- 23.Ndonky A, Oliveau S, Lalou R, et al. . Mesure de l’accessibilité géographique aux structures de santé dans l’agglomération de Dakar. Cybergeo. 2015. doi: 10.4000/cybergeo.27312. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.La Banque Mondiale . “La bourse familiale, un coup de pouce indispensable pour briser le cycle de la pauvreté.” 2019. Available from: https://www.banquemondiale.org/fr/news/feature/2019/06/14/the-family-allowance-a-critical-boost-to-help-break-the-chain-of-intergenerational-poverty