Abstract

Chlorpyrifos (CPF) is an organophosphate (OP) pesticide that causes acute toxicity by inhibiting acetylcholinesterase (AChE) in the nervous system. However, endocannabinoid (eCB) metabolizing enzymes in brain of neonatal rats are more sensitive than AChE to inhibition by CPF, leading to increased levels of eCBs. Because eCBs are immunomodulatory molecules, we investigated the association between eCB metabolism, lipid mediators, and immune function in adult and neonatal mice exposed to CPF. We focused on lung effects because epidemiologic studies have linked pesticide exposures to respiratory diseases. CPF was hypothesized to disrupt lung eCB metabolism and alter lung immune responses to lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and these effects would be more pronounced in neonatal mice due to an immature immune system. We first assessed the biochemical effects of CPF in adult mice (≥ 8 weeks old) and neonatal mice after administering CPF (2.5 mg/kg, oral) or vehicle for 7 days. Tissues were harvested 4 h after the last CPF treatment and lung microsomes from both age groups demonstrated CPF-dependent inhibition of carboxylesterases (Ces), a family of xenobiotic and lipid metabolizing enzymes, whereas AChE activity was inhibited in adult lungs only. Activity-based protein profiling (ABPP)-mass spectrometry of lung microsomes identified 31 and 32 individual serine hydrolases in neonatal lung and adult lung, respectively. Of these, Ces1c/Ces1d/Ces1b isoforms were partially inactivated by CPF in neonatal lung, whereas Ces1c/Ces1b and Ces1c/BChE were partially inactivated in adult female and male lungs, respectively, suggesting age- and sex-related differences in their sensitivity to CPF. Monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL) and fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) activities in lung were unaffected by CPF. When LPS (1.25 mg/kg, i.p.) was administered following the 7-day CPF dosing period, little to no differences in lung immune responses (cytokines and immunophenotyping) were noted between the CPF and vehicle groups. However, a CPF-dependent increase in the amounts of dendritic cells and certain lipid mediators in female lung following LPS challenge was observed. Experiments in neonatal and adult Ces1d−/− mice yielded similar results as wild type mice (WT) following CPF treatment, except that CPF augmented LPS-induced Tnfa mRNA in adult Ces1d−/− mouse lungs. This effect was associated with decreased expression of Ces1c mRNA in Ces1d−/− mice versus WT mice in the setting of LPS exposure. We conclude that CPF exposure inactivates several Ces isoforms in mouse lung and, during an inflammatory response, increases certain lipid mediators in a female-dependent manner. However, it did not cause widespread altered lung immune effects in response to an LPS challenge.

Keywords: chlorpyrifos, organophosphates, 2-arachidonoylglycerol, carboxylesterases, endocannabinoids, pulmonary inflammation

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Despite restrictions limiting its use in commercial and household settings, chlorpyrifos (CPF) remains a commonly used organophosphate (OP) insecticide and continues to be a potential exposure risk for those living in agricultural communities.1, 2 In addition to its occupational exposure risks in adults, there is also evidence that children are exposed to this compound.3-5 Furthermore, childhood exposures to CPF have been linked to developmental neurotoxicities, such as altered brain morphology, cognitive disabilities, motor skill deficits, and decreased IQ and working memory.6-8 Following its absorption, CPF is biotransformed in the body into a bioactive metabolite – termed chlorpyrifos-oxon (CPO; Figure 1) – that inhibits acetylcholinesterase (AChE) in the central nervous system and at neuromuscular junctions when administered at high doses, thereby inducing acute signs of cholinergic crisis.9, 10 In addition, non-cholinergic serine hydrolases in laboratory animals are also susceptible to inhibition following CPF treatment at doses that induce minimal AChE inhibition. For example, enzymes that metabolize lipid mediators called endocannabinoids (eCBs), such as fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) and monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL), are particularly susceptible to inactivation.11, 12

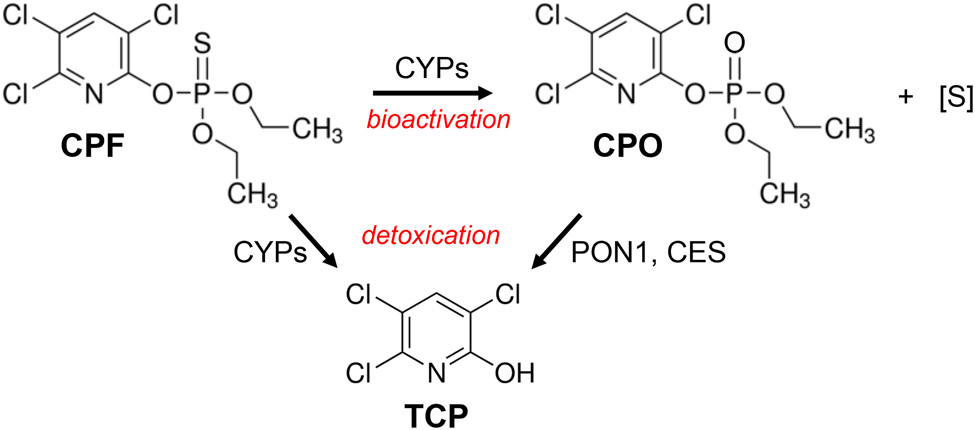

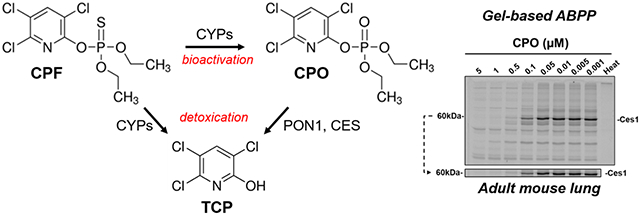

Figure 1.

Chemical schematic describing the bioactivation of CPF to CPO, the bioactive metabolite of the parent insecticide, and the detoxication pathways of CPF and CPO that yield 3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridinol (TCP). CYPs, cytochrome P450s; PON1, paraoxonase-1; CES, carboxylesterase; [S], elemental sulfur.

Since its discovery in central and peripheral tissues in the 1990s, the eCB system has been shown to have important roles in a wide range of physiological processes, including those involved in brain development, immunity, and energy metabolism.13, 14 Given the sensitivity of eCB metabolizing enzymes to inhibition by oxon metabolites,15 the disruption of the eCB system following OP exposures could lead to detrimental effects in multiple ways. For example, juvenile rats exposed to sub-chronic low-dose CPF exhibited marked reductions in FAAH and MAGL activities in brain, whereas AChE activity was not altered.16-18 At the same time, the respective eCB substrates for these enzymes (i.e. anandamide (AEA) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG)) were significantly increased in the brain as a result.16 Interestingly, these biochemical effects correlated with decreased measures of juvenile rat anxiety17 and adolescent social behavior.19 In addition to their roles in the brain, eCBs also have important functions in the immune system although several contradictory effects have been reported.20 Immunomodulatory effects induced by eCBs are typically reported as being anti-inflammatory; for example, their ability to decrease pro-inflammatory cytokines has been well characterized.21-24 On the other hand, eCBs have also been shown to exert pro-inflammatory effects in the context of atherosclerosis and allergic inflammation.25, 26 Thus, the homeostatic and pathophysiological actions exerted by the eCB system are complex and several data gaps exist, particularly in settings of environmental toxicant exposures.

Carboxylesterases (gene annotations are Ces and CES for murine and human, respectively) are also members of the serine hydrolase superfamily and have roles in the hydrolytic metabolism of pesticides and lipids.27, 28 They are expressed in multiple tissues and are an important binding site for CPO that aids its detoxication (Figure 1).29 Ces/CES enzymes react in a 1:1 stoichiometric ratio with oxons, which for CPO yields a diethylphosphorylated adduct on the active-site serine residue resulting in an inactivated enzyme.30 In contrast to humans, which have only one protein-encoding CES1 gene and one protein-encoding CES2 gene, the murine genome contains at least eight Ces1 and eight Ces2 genes that exhibit a high degree of sequence homology within each gene family.31 The Ces1d isoform is considered to be the murine orthologue of human CES1, in terms of both sequence homology and function.28 Although Magl/MAGL (Magl in rodents, MAGL in humans) is the primary 2-AG hydrolytic enzyme in both mammalian brain and human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs),32, 33 human CES1 and CES2 isoforms were also shown to hydrolyze 2-AG.34, 35 Indeed, recombinant human CES1 and MAGL each hydrolyzed 2-AG with similar catalytic efficiencies (kcat/Km).34, 36 Thus, it is possible that Ces/CES enzymes have an important backup role as a 2-AG hydrolytic enzyme in tissues where Magl/MAGL is either not expressed or present at low levels. Because CES1 is expressed in human monocytes/macrophages and can metabolize immunomodulatory lipids, such as eCBs and prostaglandin glyceryl esters,34, 35, 37 the CES enzymes might have underappreciated roles in lipid mediator metabolism and immune responses. Indeed, our previous study demonstrated that 2-AG hydrolytic activity in mouse spleen was downregulated during lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammation.38 Further, on the basis of activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) of serine hydrolases in spleen, this effect was attributed to an LPS-mediated selective decrease in Ces2g activity, while Magl activity was not altered. Taken together, these studies indicated that Ces/CES enzymes are capable of metabolizing bioactive lipids, they are sensitive targets of oxon poisons, and suggested that their enzymatic activity can be modulated in settings of inflammation.

The lung is known to express a large quantity of Ces/CES enzymes39 and it is an obvious site of inflammation following pathogen exposure. Rat lung microsomes and pulmonary alveolar macrophages contain a Ces activity that can hydrolyze the insecticides malathion and phenthoate.40 Furthermore, intranasal inoculation with Pseudomonas aeruginosa induced this activity in alveolar macrophages (the specific Ces isoform was impossible to know at the time) without affecting the same activity in lung tissue microsomes.40 This suggested that Ces in alveolar macrophages might have an adaptive function following exposure to lung pathogens and a role in immune responses. Several epidemiological studies have suggested a link between exposure to pesticides and respiratory illness, chronic bronchitis, airway hypersensitivity, and asthma.41-45 Although the mechanisms for these effects are not known in all cases, OP pesticides can cause airway hypersensitivity though a mechanism that does not involve direct AChE inhibition. Rather, it might involve dysregulated neuronal M2 muscarinic receptor function on parasympathetic neurons.9, 46, 47 There is also evidence that CPF can induce pro-inflammatory cytokines in human THP-1 monocytes/macrophages,48 which is relevant because IL-1β and TNF-α were shown to downregulate M2 receptors in guinea pig lung and a human embryonic lung cell line.49, 50 How pesticides such as CPF activate lung inflammatory cells and/or epithelial cells and induce cytokine production has not been established.9 Outside of studies on asthma, few laboratory investigations have focused on the links between pesticides and respiratory illness. One study found no difference in the extent of LPS-induced lung inflammation following 90-day oral exposures of mice to ethion (an OP insecticide) and vehicle.51 On the other hand, mice exposed to methamidophos in drinking water from gestation day 10 to postnatal day 21 had lower levels of IL-6 following infection with respiratory syncytial virus.52 However, on the whole, there is a paucity of laboratory data that have examined the relationship between pesticides and lung health.

Given that (i) Ces enzymes are present in both pulmonary macrophages and lung epithelial cells and can metabolize lipid mediators,34, 35, 53 (ii) alveolar macrophages possess Ces activity capable of hydrolyzing pesticides,40 and (iii) evidence exists that pesticides affect viral respiratory immune responses,52 we opted to explore the ability of CPF to alter lung immune responses through a mechanism involving the eCB system in a murine model of LPS-induced inflammation. Further justification for examining lung Ces enzymes in the context of CPF exposure and inflammation comes from our observations that adult female Ces1d−/− mice exhibit heightened levels of lung Il6 mRNA compared to their WT counterparts following an LPS challenge.54 Therefore, the objectives of the present study were to determine whether sub-acute, low-dose CPF exposure can inactivate eCB metabolizing enzymes in the lungs of neonatal and adult mice and whether this exposure modulates LPS-induced inflammation. First, the effect of oral CPF treatment on eCB metabolic enzyme activity in lung was determined. Second, ABPP identified those serine hydrolases in lung that were inhibited by CPF treatment. Selective small-molecule inhibitors of Magl and Ces1d were also used to identify the 2-AG metabolizing enzymes in the lung. Finally, we assessed whether CPF could modulate immune responses in mouse lung following an LPS challenge administered after seven consecutive days of CPF treatment, and if any of the observed effects could be connected to CPF-dependent inactivation of eCB catabolic enzymes.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Chemicals and Reagents.

Chlorpyrifos (>99%, determined by HPLC-photodiode array analysis) was a generous gift from DowElanco Chemical Company (Indianapolis, IN). Antibodies for flow cytometry and ELISA were purchased from Biolegend. Authentic standards of lipid mediators were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Solvents for LC-MS/MS were from Thermo Fisher. p-Nitrophenyl valerate (pNPVa) and LPS (E. coli 0111:B4) were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Antibodies for western blots were from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). The activity probes fluorophosphonate (FP)-biotin and FP-TAMRA were from Toronto Research Chemicals (North York, ON) and Thermo Fisher, respectively. Reagents for ABPP-mass spectrometry (MS) were from sources described in Wang et al.35

Animal Studies.

C57BL/6 wild type (WT) mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) and used to establish a breeding colony in a murine norovirus-free facility. Adult WT mice were bred on site or purchased and acclimated for one week before experiments. Neonate and adult (7-8 weeks) male and female mice were used for these experiments. Global Ces1d−/− mice on a C57BL/6 background were established as previously described55 and used to establish a breeding colony in a separate facility due to their origin from a facility where murine norovirus is endemic. Mice from the WT breeding colony were relocated to this facility to establish a breeding colony to serve as controls for the Ces1d−/− mice. Genotypes of both sets of mice were confirmed prior to initiating experiments; both neonate and adult male mice were used for the knockout studies. All mice were housed in temperature- and humidity-controlled AAALAC-approved facilities (20-25 °C and 40-60% humidity) under a 12-h light cycle and used in accordance with the Mississippi State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Animal Treatment and Tissue Collection.

CPF was dissolved in research-grade corn oil (CO, Sigma, C8267, Lot #MKBS6944V) and administered at a volume of 1 mL/kg body weight for adult mice (7-8 weeks) or 0.5 mL/kg for neonatal mice. For neonatal studies, the day of birth was designated as postnatal day 0 (PND 0). Neonatal mouse pups (PND 4-10 or 10-16, n=4-8, randomized from 2-3 litters) received either CO or CPF (2.5 mg/kg) orally every day for 7 days. Solutions were delivered to the back of the throat using a 25-μl tuberculin syringe equipped with a 1-inch x 24-gauge straight intubation needle. Adult mice (n=5/sex/group) received either CO or CPF (2.5 mg/kg) by oral gavage every day for 7 days. Body weights were recorded during the treatment period. The CPF dose was chosen on the basis that it does not significantly alter brain AChE activity.56-59 At 4 h after the final CPF dose, mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation and tissues (lung, liver, spleen, and brain) collected and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. In some studies, trunk blood was collected immediately following cervical dislocation and serum prepared by centrifuging the clotted blood (4°C, 10 min, 3,000 x g). All frozen tissues and sera were stored at −80°C until further use.

Immune Studies.

CPF or CO was administered to mice (WT and Ces1d−/−) as described above. At 0.5 h after the final dose, adult mice (n=5/sex/group, repeated 3x in males) or neonatal mice (PND 10-16, n=9-13/group, randomized from 6 litters) were injected with LPS (1.25 mg/kg, i.p.) or saline in a volume of 100 μL/adult and 50 μL/neonatal mouse. The LPS dose was the same as that of our previous studies.38 Six hours after LPS injection, mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation and tissues collected. The right inferior lung lobe was placed in 1x PBS and stored on ice until further processing immediately following collection of all tissues. The right middle lung lobe was placed in RNA later™ (Thermo Fisher) before flash-freezing and storing at −80°C until use. The remaining lung lobes and additional tissues were flash-frozen and stored at −80°C. In immune studies that compared WT and Ces1d−/− mice, adults (n=4/group, only LPS treatments in WT mice) or neonates (PND 10-16, n=5/group, randomized from 4 litters for each genotype) from WT or Ces1d−/− mice were used.

Isolation and Culture of Alveolar Macrophages.

Alveolar macrophages were obtained from untreated C57BL/6 wild-type adult mice by bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and pooled. Following sacrifice, the trachea was exposed, and a 22-gauge catheter was inserted into the trachea. One-mL 1x PBS containing 3% FBS was injected into the lungs and withdrawn 5-7 times per mouse. Cells in the pooled BAL fluid were collected, washed, and plated in culture dishes overnight at 37 °C in 5% CO2 atmosphere to allow macrophages to adhere. Alveolar macrophages were left as naïve or treated with LPS (100 ng/mL) for 24 hours at 37 °C. After 24 hours, RNA was extracted for RT-qPCR as described below.

Preparation of Tissue Homogenates.

Whole-tissue homogenates (lung, liver, spleen, and brain) were prepared on ice at 20% w/v in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) buffer using a Dounce homogenizer. The crude homogenates were centrifuged at low speed to remove debris (4 °C, 20 min, 1,000 x g). For some studies, lung subcellular fractions were prepared: lungs were homogenized in sucrose buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 0.32 M sucrose, pH 7.4), centrifuged at low speed (4 °C, 5 min, 1,000 x g), and the resulting supernatant was centrifuged at high speed (4 °C, 60 min, 100,000 x g). The resulting pellet was washed and resuspended in sucrose buffer by sonication, then re-centrifuged (4 °C, 60 min, 100,000 x g); this wash step is critical for removing contaminating soluble blood components. The final pellet was sonicated in 400 μL of sucrose buffer to give washed lung microsomes. All homogenates and microsomes were stored at −80 °C until analysis. Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA reagent (ThermoPierce) with bovine serum albumin standards.

Forebrain and Lung AChE Activity.

The forebrain was homogenized as previously described60 and an aliquot of homogenate was diluted in cold 0.05 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4 at 37°C) at a final tissue concentration of 0.625 mg/mL. AChE activity was measured spectrophotometrically using a modification61 of Ellman et al.62 with acetylthiocholine as the substrate (1 mM final concentration) and 5,5’-dithiobis(nitrobenzoic acid) as the chromogen. Protein concentrations were quantified with the Folin phenol reagent using bovine serum albumin as a standard.63 ChE activity of lung (washed microsomes or cytosols from the post-caval lung lobe) was monitored spectrophotometrically for 10 min at 412 nm in a microplate. Some samples were pretreated with iso-OMPA (10 μM final concentration) to distinguish acetylcholinesterase and butrylcholinesterase activities. Non-enzymatic control samples were prepared utilizing eserine sulfate (10 μM final concentration), a pan-esterase inhibitor. The resulting slopes were standardized to protein (BCA method) to give specific enzyme activities.

Endocannabinoid Hydrolysis Assays.

Fifty μg of tissue homogenate or microsomal protein was added to 100 μL of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) buffer. Samples were pre-incubated for 5 min at 37°C, then 2-AG or AEA was added to a final concentration of 50 μM and the samples incubated at 37°C for 20 min. The reactions were quenched with 200 μL of cold acetonitrile containing an internal standard (2.5 μM of arachidonic acid-d8). After sitting on ice for 10 min, the samples were centrifuged (4°C, 10 min, 16,100 x g) and the resulting supernatant transferred to HPLC vials containing volume-reducing inserts. The samples were stored at −20°C until analysis by LC-MS/MS. ‘Blank’ samples of each tissue homogenate (i.e., not supplemented with exogenous 2-AG or AEA) were prepared to account for endogenous arachidonic acid levels. Non-enzymatic control samples were also prepared; these contained 2-AG or AEA but not tissue homogenate. For some naïve lung microsomes (both neonate and adult), the samples were preincubated with vehicle (DMSO), WWL113 (Ces1d inhibitor, 1 or 10 μM), JZL184 (Magl inhibitor, 1 or 10 μM), CPO (1 μM), or paraoxon (PO, 1 μM) for 30 min at 37°C before adding exogenous 2-AG substrate.

Determination of Ces Activity Using pNPVa.

An appropriate amount of tissue homogenates, serum, or microsomes were diluted in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) and pre-incubated for 5 min at 37°C. pNPVa was added to reactions at a final concentration of 750 μM, and the production of the hydrolysis product (para-nitrophenol) was monitored at 405 nm for a period of 5 min. Enzyme activities were normalized on protein amounts to give specific enzyme activities.

Gel-based Activity-Based Protein Profiling and Western Blotting.

Lung homogenates were diluted in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) to yield a final protein concentration of 1 mg/mL in a 50-μL reaction volume. FP-biotin was added to give a final concentration of 8 μM and the samples allowed to react at room temperature for 1 h. Negative control reactions were heated for 5 min at 90°C before adding FP-biotin. All reactions were quenched by adding 10 μL of 6x SDS-loading buffer (reducing) then heating at 90°C for 5 min. After samples cooled, proteins were separated on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel (25 μg protein per well) and transferred to a PVDF membrane. After blocking the membrane with 5% w/v non-fat milk in Tween buffer, biotinylated proteins were detected with using avidin-peroxidase (Sigma, 1:1000 v/v diluted in Tween buffer) and Thermo Supersignal West Pico ECL reagent. Chemiluminescent signals were visualized on film and serine hydrolases tentatively identified based on their molecular weight and by comparison to previous publications.38, 64, 65 After visualizing the biotinylated proteins, the PVDF membranes were stripped and re-probed with a rabbit monoclonal anti-human CES1 antibody (Abcam Cat# 2312-1, RRID:AB_1266968; antibody cross-reacts with mouse Ces1 isoforms). In a separate experiment, the FP-TAMRA probe was used to examine serine hydrolase activities in lung microsomes following their pre-incubation with increasing concentrations of CPO (30 min, 37 °C), as previously described.37

Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP-Mass Spectrometry).

Lung proteomes (microsomes) were adjusted to a concentration of 1 mg/mL protein in a volume of 1 mL of 50 mM Tris-HCl (adult female lung was <1 mg/mL due to limited protein amounts). For adults, the biological replicate represents one individual animal, whereas for neonates the biological replicate represents the combination of lungs from two individual animals (i.e., because of their smaller size, two individual neonate lungs were pooled to make one sample). Each sample was treated with FP-biotin and prepared for proteomic analysis as previously described,38 until the desalting step. Samples were desalted using Thermo Scientific Pierce peptide desalting spin columns following the manufacturer’s instructions and solvents were evaporated in a Speedvac concentrator. Peptide samples were sent to the UC Davis proteomics core facility for analysis using a Q-Exactive mass spectrometer and the data analyzed (protein identification and quantification) as previously described.35 Spectral counting is a semiquantitative method that counts the number of tandem mass spectra (MS2 data) collected for each detected peptide.66-68 The assumption that underlies spectral counting is that a linear relationship exists between a protein’s abundance and its degree of sampling during an LC-MS/MS run (i.e., the number of spectral counts detected per peptide). This assumption has been validated in several studies.67-70 We chose spectral counting in the current study because its utility has been well established by several groups.35, 67, 71-78

Lung Immunophenotype by Flow Cytometry.

Right inferior lung lobes were homogenized on ice in 1x PBS using a pellet pestle and motorized grinder immediately following their collection. The homogenate was passed through a 70-μm sieve, followed by a 35-μm mesh strainer to obtain a single-cell suspension that was subsequently stained for adaptive and innate immune cell markers. Individual cells were blocked with Fc block (CD16/32; BD Biosciences Cat# 553142, RRID:AB_394657) then stained using one of two protocols. To detect adaptive immune cells, lung cells were stained with extracellular antibodies for CD4 (PECy5; BioLegend Cat# 100410, RRID:AB_312695), CD8 (PECy7; BioLegend Cat# 100722, RRID:AB_312761), and CD19 (BV650; BioLegend Cat# 115543, RRID:AB_11218994). Innate immune cells were stained with extracellular antibodies for CD49b (FITC; BioLegend Cat# 103504, RRID:AB_313027), F4/80 (PECy7; BioLegend Cat# 123114, RRID:AB_893478), CD11b (APC; BioLegend Cat# 101212, RRID:AB_312795), CD11c (PE; BD Biosciences Cat# 553802, RRID:AB_395061), and Gr1 (PacBlue; BioLegend Cat# 108430, RRID:AB_893556). All cells were fixed in BD Cytofix™ (BD Biosciences) following staining. An ACEA Novocyte Flow Cytometer was used to analyze the stained and fixed cells. Antibody-capture beads were used as compensation controls and fluorescent-minus one controls were used to set gates. Adaptive immune cells were identified as cytotoxic T cells (CD8+), T helper cells (CD4+), or B cells (CD19+) and quantified as the percentage of the parent lymphocytes (Supporting Information, Figure S1A). Using previously reported staining protocols,79, 80 innate immune cells were identified as natural killer cells (CD49+, CD11b−), alveolar macrophages (F4/80+, CD11c+, CD11b−), monocytes (F4/80+, CD11b+, Gr1−), dendritic cells (CD11b+, CD11c+), or neutrophils (CD11b+, CD11c−, Gr1+) and quantified as the percentage of the parent immune cells (Figure S1B).

Lung mRNA Extraction and Gene Expression Analysis by Quantitative RT-PCR.

Total RNA from the right middle lung lobe was extracted following the manufacturer’s instructions utilizing a RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen). RNA was quantified on a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer before preparing cDNA with a RevertAid First Strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time PCR was performed with SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Qiagen) on a Stratagene Mx3005P thermocycler. The list of primers used for RT-qPCR analysis is given in Table S1 (Supporting Information). GAPDH was used as the reference gene and the comparative cycle threshold (ΔΔCT) was used to determine gene expression changes, with results compared to the control condition [(2−ΔΔCT)]. WT control mice from each experiment were utilized as the control condition except in the experiment utilizing adult Ces1d−/− mice, where Ces1d−/− mice treated with CO and saline were set as the control due to the lack of a WT saline group.

Cytokine Determination by ELISA.

The left lung lobe was homogenized, lysed, and prepared for ELISA as previously described.81 IL-6 was measured by sandwich-based ELISA utilizing a previously described protocol and anti-mouse IL-6 antibodies (Biolegend).32 IL-1β and TNF-α were measured by ELISA using the manufacturer’s protocol (Thermo Fisher).

Analysis of Lung Lipid Mediators.

Lipid mediators, including endocannabinoids, N-acylethanolamines, and select eicosanoids, in the right superior lung lobe were extracted as previously described.82 One-hundred μL of methanol was added to the dried extracts and transferred to HPLC vials with volume-reducing inserts for analysis by LC-MS/MS as previously described.35

Statistical Methods.

The number of mice used for experiments are provided in the Figure captions. Although the sex was recorded, male and female neonatal data were combined for analysis because there were no differences between sexes. The mean and standard deviation (or standard error of mean) was calculated for each experimental group. A Student’s t-test, one-way ANOVA, or two-way ANOVA assessed differences between experimental groups and employed either GraphPad Prism (Version 7, San Diego, CA, USA) or SigmaPlot (Version 11.0, San Jose, CA, USA). Grubb’s outlier test was used to identify outliers in data sets. Data from flow cytometry and quantitative RT-PCR were log-transformed prior to analysis. p-values <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

CPF Did Not Alter Mouse Weight or Inhibit Brain AChE Activity in Neonates and Adults, Whereas it Did Inhibit Lung AChE Activity in Adults but Not Neonates.

Treatment of mice with 2.5 mg/kg CPF (oral) for 7 consecutive days did not alter the weights of adults of either sex when compared to CO controls (Figure S2A). In addition, no differences were noted in the rates of weight gain of neonatal mice treated with CPF and CO during the PND 10-16 and PND 4-10 periods (Figures S2B and S2C, respectively). Importantly, CPF treatment did not inhibit brain AChE activity in either neonate or adult mice as compared to their corresponding CO controls (Figure S3A,B). On the other hand, our treatment regimen inhibited lung microsomal and cytosolic AChE activity in adult mice but not neonates (Figure S3E,G). BChE activity (Figure S3F,H) was also inhibited in lung microsomal and cytosolic fractions from all ages and sexes, except microsomes from adult female mice.

CPF Had Minimal Effects on Endocannabinoid Hydrolysis Activity.

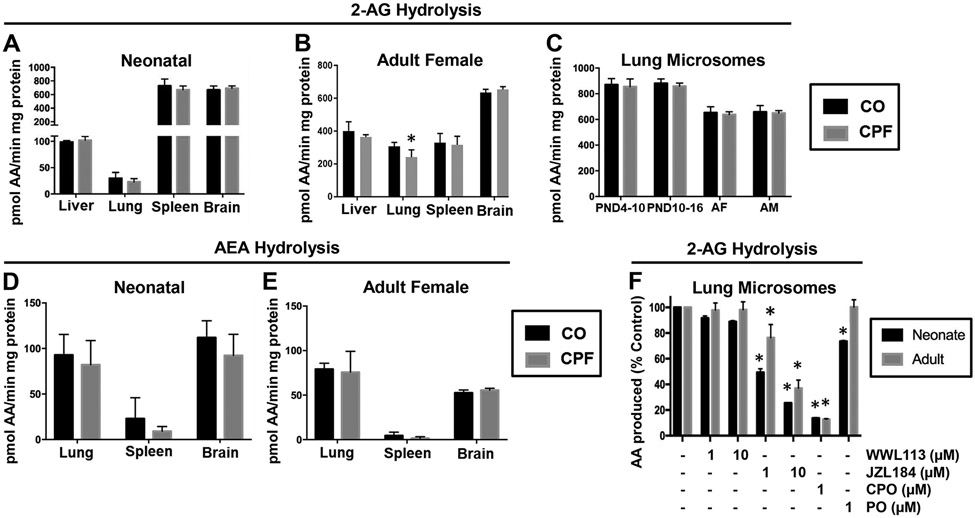

2-AG hydrolysis specific activities in neonate mouse tissues under control (CO) conditions followed the rank order: brain≈spleen>>liver>lung (Figure 2A), whereas in adult female the 2-AG hydrolysis activity in brain was higher than that in liver, lung, and spleen (Figure 2B). Females were used for initial evaluation of adult mice because female mice have been shown to be more susceptible to some types of pulmonary disease.83, 84 CPF treatment did not alter 2-AG hydrolytic activities in liver, spleen, and brain of either neonatal mice (treated from PND 10-16) or adult mice (Figure 2A,B). However, it slightly inhibited this activity in adult female lung (p=0.0495) but not in neonatal lung. Because Ces isoforms and Magl are located primarily in the membranes (microsomes) of tissue subcellular fractions, the 2-AG hydrolysis activity of lung microsomes was determined for all age groups (Figure 2C). CPF treatment, however, did not alter the 2-AG hydrolytic activity of lung microsomes from any age group. Male and female adult mice were used for these experiments, but no sex differences were noted. CPF treatment also did not alter AEA hydrolytic activities in lung, spleen, and brain of either neonate mice (Figure 2D) or adult female mice (Figure 2E). Lung and brain AEA hydrolysis activities in neonate and adult mice were comparable to each other, whereas much lower activity was present in the spleen. Together these results indicated that eCB metabolism activities were not significantly affected by CPF treatment.

Figure 2.

2-AG and AEA hydrolysis activity in tissues obtained from CPF- and vehicle (CO)-treated mice. 2-AG hydrolysis activities in whole-tissue homogenates of brain, liver, lung, and spleen from neonatal mice (A) and adult female mice (B) (n=4-5). (C) 2-AG hydrolysis activities in lung microsomes from neonate (n=2-4) and adult mice (n=5; AF, adult female; AM, adult male). AEA hydrolysis activities in whole-tissue homogenates of brain, liver, lung, and spleen from neonatal mice (D) and adult female mice (E) (n=4-5). Data are presented as mean ± SD; *p<0.05 relative to CO control. (F) 2-AG hydrolytic activity in neonate and adult lung microsomes (n=2-3 per condition) was assessed by pre-incubation of microsomes with inhibitors or vehicle (DMSO) prior to adding exogenous 2-AG. Data are expressed as percent vehicle control (mean ± SD). Statistical significance was assessed by two-way ANOVA and Sidak’s multiple comparison test.

Pharmacological inhibitors of Ces1c, Ces1d, and Magl were utilized to identify the 2-AG hydrolytic enzyme(s) in neonate and adult lung microsomes (Figure 2F). JZL184 (Magl inhibitor) inhibited 2-AG hydrolytic activity by >50% at concentrations of 1 and 10 μM. WWL113 (Ces1c and Ces1d inhibitor), on the other hand, had minimal effects (<20% inhibition at 10 μM). CPO, which is a promiscuous inhibitor of serine hydrolases,11 caused the greatest degree of inhibition (~80%); whereas PO, which is a more selective inhibitor than CPO at 1 μM,34 inhibited ~25% of the 2-AG hydrolytic activity. These results, taken together, suggested that Magl is the primary 2-AG hydrolytic enzyme in lung microsomes, although other enzymes such as Ces1d and Ces1c probably have a minor role in metabolizing 2-AG.

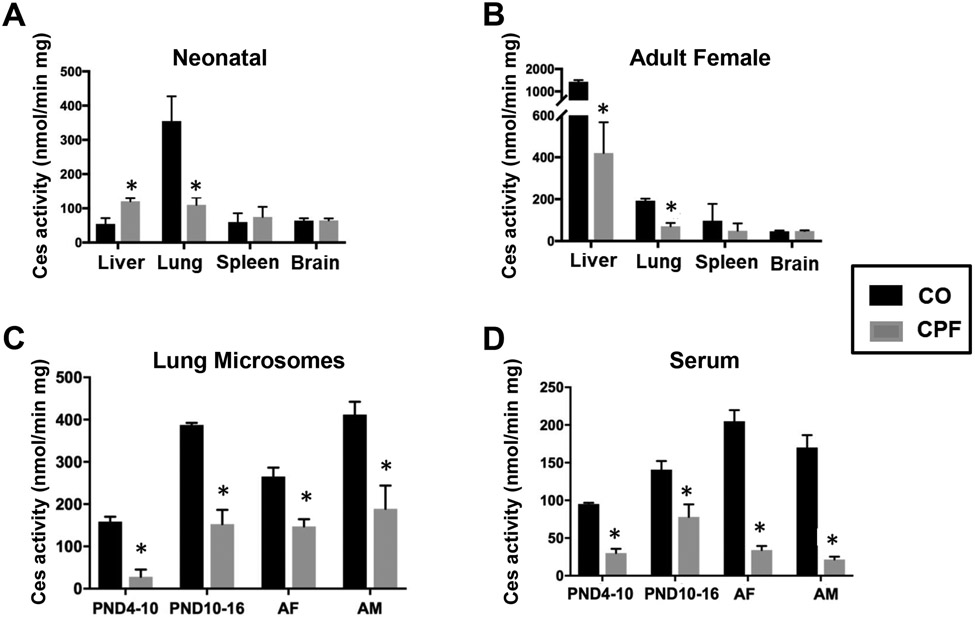

CPF Altered Carboxylesterase Activity.

CPF treatment significantly inhibited Ces activity (assessed using the pan-Ces substrate pNPVa)85 in whole tissue homogenates of lungs from neonatal and adult female mice (Figure 3A,B), whereas it did not alter Ces activity in brain and spleen. Ces activity in adult liver was inhibited by CPF, whereas it was slightly increased in neonate liver (Figure 3A,B). Ces activities in lung microsomes (Figure 3C) and serum (Figure 3D) in neonatal and adult mice of both sexes were markedly inhibited by CPF treatment. Thus, Ces enzymes in mouse lungs from all age groups were sensitive targets of inactivation.

Figure 3.

Ces activity in tissues obtained from CPF- and vehicle (CO)-treated mice. Whole-tissue homogenates of liver, lung, spleen, and liver from neonatal (A) and adult female mice (B) (n=4-5). Ces activity in lung microsomes (C) or serum (D) from neonatal mice exposed during PND 4-10 (n=3-4) and PND 10-16 (n=2-4), or during adulthood (n=5, AF, adult female; AM, adult male). Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was assessed using a two-way ANOVA and Sidak’s multiple comparison test; *p<0.05 relative to CO control.

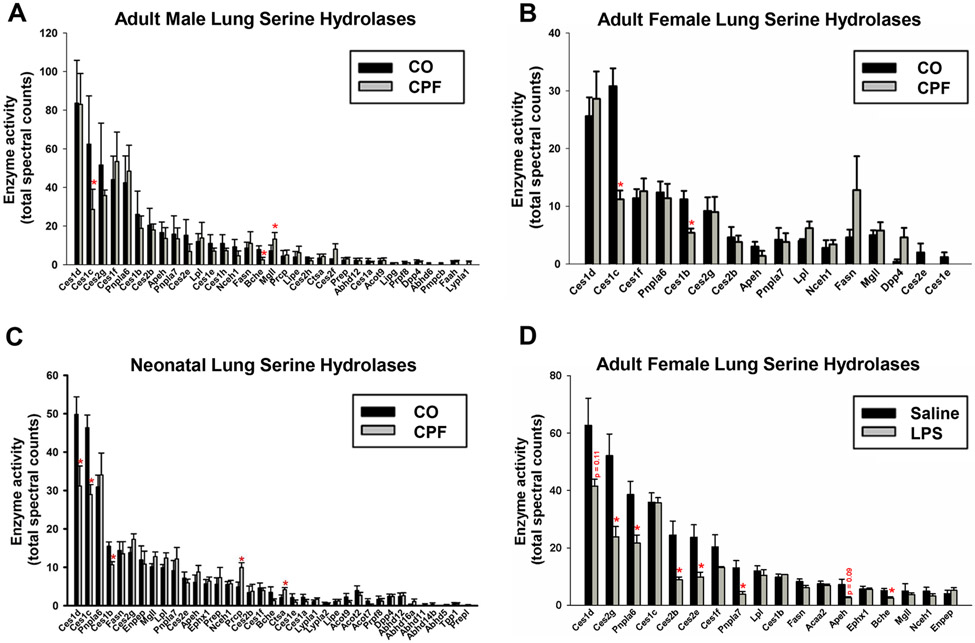

CPF Inhibited Multiple Ces1 Isoforms in Lung in an Age-Dependent Manner.

We employed the ABPP approach to determine which serine hydrolases in lung were inactivated by CPF treatment. This method evaluates intrinsic enzyme activities in tissues by using activity probes that assess the conserved catalytic mechanism of the interrogated enzyme family.78 For example, the catalytic serine residue of serine hydrolases are covalently labeled by FP-biotin, whereas inactive enzymes cannot react with this probe. ABPP-MS of lung microsomes obtained from CO- and CPF-treated mice detected 32, 16, and 31 serine hydrolases in adult male, adult female, and neonatal mice, respectively (Figure 4A-C). The smaller number detected in females was likely due to the lower protein yield in the microsomal preparation. CPF treatment partially inactivated Ces1d, Ces1c, and Ces1b in neonatal mice. In addition, it partially inactivated Ces1c and Ces1b in adult female mice, whereas Ces1c and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) were inactivated in adult male mice. Thus, Ces1 isoforms in lung are prominent targets for inhibition following CPF treatment, while Mgll (also annotated Magl) was not inactivated. In addition, Faah was undetectable in mouse lungs from all age groups, whether from animals treated with CPF or not.

Figure 4.

ABPP-MS of mouse lung microsomes obtained from CPF- and vehicle (CO)-treated mice (A-C), or LPS- and saline-treated mice (D). Serine hydrolases identified in murine lungs from neonatal mice (n=7 biological replicates, 14 mice per condition) (A), adult female mice (n=5 mice per condition) (B), adult male mice (n=6 mice per condition) (C), and adult female mice (n=5 mice per condition) (D). Following sacrifice, mouse lungs were harvested and processed for ABPP-MS, as described previously 35. Serine hydrolases are denoted by their gene symbols and those with significantly reduced activity are denoted by a red asterisk. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n=5-7 mice per condition); *p<0.05 relative to CO control or saline control.

A separate cohort of adult female mice was treated with LPS (no CPF) to assess how inflammation affects serine hydrolase activities in lung. Six hours after LPS injection, ABPP-MS showed that Ces2g, Ces2b, and Ces2e activities in lung were significantly decreased compared to those from saline controls (Figure 4D). Ces1d activity trended downward but it did not reach statistical significance (p=0.11), while Ces1c and Mgll activities were notably unaffected.

CPF Inhibited Lung Ces1 Activity Without Altering Ces1 Protein Abundance.

Gel-based ABPP is another format in which activity probe-labeled proteins are separated by SDS-PAGE.78 In this case, treatment of lung proteomes with FP-biotin resulted in the detection of Ces1, which constitutes multiple isoforms of MW~60 kDa (the most prominent in lung is Ces1d), Magl, and Nceh1 (Figure S4A). Of these, Ces1 isoforms were the only ones inactivated in neonatal and adult lungs following in vivo CPF treatment. Ces1 proteins were also detected in lung proteome samples by using an antibody that recognizes murine Ces1 orthologues. Importantly, CPF treatment did not alter the collective levels of Ces1 protein(s), as indicated by its consistent signal intensity in the control and CPF lung proteomes (Figure S4A, western blot, bottom). This finding was further confirmed by in vitro reactions using the probe FP-TAMRA, which contains a fluorophore tag instead of biotin. Pretreatment of naïve lung microsomes with the bioactive CPO metabolite prior to reaction with a fixed amount of FP-TAMRA caused the fluorescent intensity of the Ces1 band (60 kDa) in the activity gel to be reduced in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure S4B; IC50 = 77 nM). Therefore, because Ces1 protein expression appears to be unchanged by in vivo CPF exposure, whereas their activities are decreased after in vivo and in vitro treatments, the most logical explanation is that these enzymes undergo direct covalent inactivation by CPO.

CPF Did Not Markedly Alter Lung Immunophenotype Following LPS Challenge.

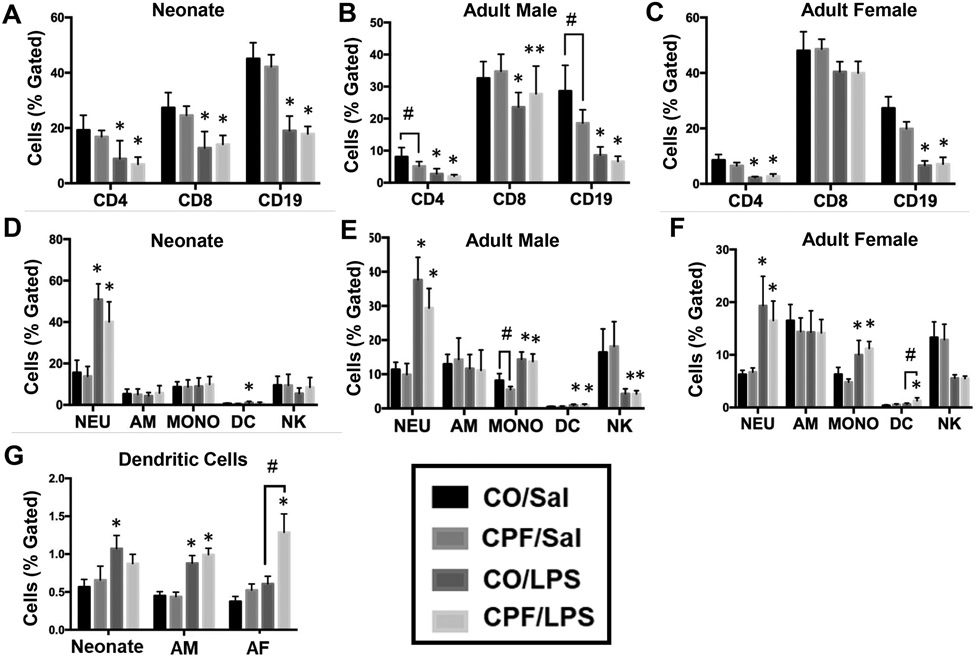

Next, we used flow cytometry to assess lung immunophenotypes following CPF treatment and subsequent LPS challenge (for gating strategy, see Figure S1). CPF treatment did not alter the distribution of adaptive and innate immune cells in response to LPS challenge in the neonate lung (Figure 5A,D), adult male lung (Figure 5B,E), or adult female lung (Figure 5C,F), with the exception of a slight increase in the percentage of dendritic cells in adult female mice (Figure 5G). In the absence of LPS, CPF treatment slightly decreased the percentage of CD4+ T cells, CD19+ B cells, and monocytes in adult male lung (Figure 5B), while there was a decreased trend in these cell types in neonate and adult female lungs (Figure 5A,C). The percentage of neutrophils (CD11b+, CD11c−, Gr1+) in all age groups of either sex increased following LPS challenge, whether mice were treated with CPF or not (Figure 5D-F). Monocytes (F4/80+, CD11b+, Gr1−) and dendritic cells (CD11b+, CD11c+) in adult mice of either sex were also increased by LPS (Figure 5E,F). In adult mice, the percentage of NK cells (CD49+, CD11b−) was significantly decreased in response to LPS, regardless of whether CPF was included (Figures 5E-F), while the percentage of alveolar macrophages (F4/80+, CD11c+, CD11b−) was similar in all treatment and age groups (Figure 5D-F). LPS challenge also decreased the percentage of T helper cells (CD4+) and B cells (CD19+) in all ages and sexes regardless of whether CPF was used, while the percentage of cytotoxic T cells (CD8+) also decreased or trended downward in neonate and adult lungs (Figure 5A-C). These data indicate that the lung immunophenotype was not substantially altered by CPF exposure.

Figure 5.

Lung innate and adaptive immunophenotypes were assessed by flow cytometry. Cells were stained for extracellular markers to identify the adaptive lung immunophenotypes of neonate mice (n=10-13) (A), adult male mice (n=15) (B), and adult female mice (n=5) (C) following LPS challenge. Cells were also stained for extracellular markers to identify the innate lung immunophenotype of neonate mice (n=9-13) (D), adult male mice (n=15) (E), and adult female mice (n=5) (F) following LPS challenge. Cells were identified as T helper cells (CD4+), cytotoxic T cells (CD8+), B cells (CD19+), natural killer cells (NK, CD49+, CD11b-), alveolar macrophages (AM, F4/80+, CD11c+, CD11b-), monocytes (MONO, F4/80+, CD11b+, Gr1-), dendritic cells (DC, CD11b+, CD11c+), or neutrophils (NEU, CD11b+, CD11c-, Gr1+). To highlight the DC populations, a separate graph is given with all ages and sexes (G). Data are expressed as the mean of percent lymphocyte gated ± SD. A two-way ANOVA and Tukey multiple comparisons test was used to assess significance; *p<0.05, **p=0.056 compared to saline controls; #p<0.05 for indicated comparison.

Because Ces enzymes have important roles as stoichiometric scavengers of oxons, we also treated neonate and adult Ces1d−/− mice with CPF to determine whether the absence of this detoxication enzyme might unmask immunomodulatory effects in lung following subsequent LPS challenge. As indicated above, Ces1d is the murine orthologue of human CES1, which is the major CES in human lung. We first established that the Ces activity of Ces1d−/− lung microsomes, determined using the substrate pNPV, was reduced by ~80% compared to that of WT lung microsomes under baseline conditions (Ces1d−/− and WT: 232±4 and 1130±4 μmol min−1 mg−1, respectively; n=3, p<0.001). In general, however, similar trends were noted in the distribution of adaptive and innate cells in lungs of neonatal and adult WT and Ces1d−/− mice (Figure S5A-D). The only difference between genotypes was the higher percentage of monocytes in neonate Ces1d−/− lungs relative to their WT counterparts, an effect that was independent of CPF or LPS treatments (Figure S5C).

CPF Did Not Alter LPS-Induced Cytokines in Lung.

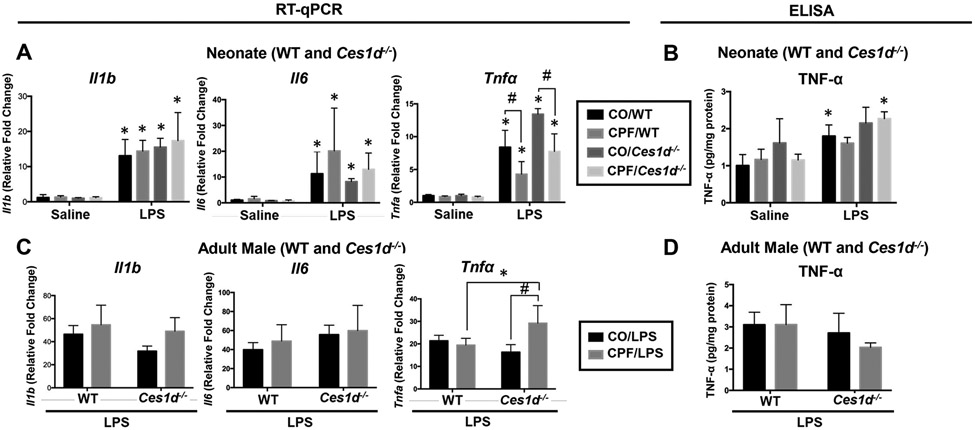

Cytokine levels in neonate and adult WT mouse lungs were evaluated by gene expression and ELISA (Figure S6A-F). LPS challenge induced a robust increase in all cytokines; however, CPF did not alter their levels, regardless of age or sex. In another experiment using neonate and adult male WT and Ces1d−/− mice, CPF treatment did not alter mRNA levels of Il1b or Il6 in response to LPS, irrespective of genotype or age (Figure 6A,C). On the other hand, CPF attenuated the LPS-induced Tnfa mRNA levels in neonate WT and Ces1d−/− mice (Figure 6A), whereas it increased Tnfa mRNA expression in adult Ces1d−/− mice but not WT mice (Figure 6C). These differences, however, were not detectable by ELISA of lung tissue extracts (Figure 6B,D).

Figure 6.

Cytokine mRNA and protein levels in WT and Ces1d−/− lungs were determined by RT-qPCR and ELISA. RNA was extracted from the right middle lung lobe and reverse transcribed to measure Il1b, Il6, and Tnfa mRNA (A,C). A sandwich-based ELISA assay was used to measure tissue cytokines (B,D). Results are shown for WT and Ces1d−/− neonatal mice (A,B, n=5) and adult mice (C,D, n=4). mRNA data are expressed as fold-change compared to vehicle/saline controls. In Ces1d−/− neonatal mice, data are compared to WT vehicle/saline controls. For Ces1d−/− adult male mice, data are compared to Ces1d−/− vehicle/saline controls. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. A two-way ANOVA and Tukey multiple comparisons test was used to assess significance; *p<0.05 compared to saline control, #p<0.05 for indicated comparisons.

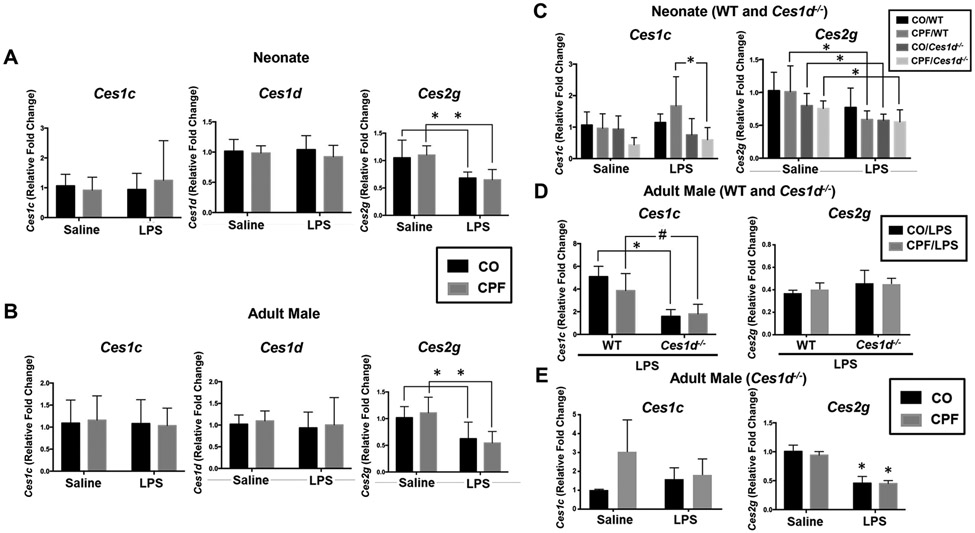

CPF Did Not Alter Ces or SP Gene Expression in Lung.

Based on previous work, the expression level of the three highest Ces mRNA species in adult C57BL/6 murine lung follows the rank order: Ces1d >> Ces2g > Ces1c.39 Therefore, we evaluated the expression of these genes in WT neonate and adult male lungs (Figure 7A,B). Although Ces1c and Ces1d expression in neonate and adult lung was unaltered by CPF and/or LPS treatment, Ces2g expression was downregulated by LPS in both age groups, irrespective of CPF treatment (Figure 7A,B). This result might explain the reduced lung Ces2g activity observed following LPS treatment (Figure 4D). Another novel observation was that Ces1d expression was detected in pulmonary alveolar macrophages from naïve WT adult mice, whereas Ces2g and Ces1c expression was undetectable (Figure S7). Interestingly, Ces1d mRNA levels were also reduced by >60% when the alveolar macrophages were challenged with LPS ex vivo (Figure S7).

Figure 7.

Ces mRNA levels were determined by RT-qPCR. RNA was extracted from the right middle lung lobe and reverse transcribed to assess the expression of genes that encode Ces isoforms in WT neonatal mice (n=9-10) (A), WT adult male mice (n=10) (B), WT and Ces1d−/− neonatal mice (n=5) (C), and adult mice (n=4) (D, WT and Ces1d−/−; E, Ces1d−/− only). Data are expressed as mean ± SD. A two-way ANOVA and Tukey multiple comparisons test was used to assess significance; *p<0.05, #p=0.0623 for indicated comparisons.

In the neonate mice on either WT or Ces1d−/− genetic backgrounds, lung Ces1c and Ces2g mRNA levels were unaffected by CPF or LPS treatments compared to their respective controls, although there was a significant difference in Ces1c mRNA levels between WT and Ces1d−/− neonate mice treated with both CPF and LPS (Figure 7C). In the setting of LPS-induced lung inflammation, Ces1c mRNA expression (but not Ces2g) was also significantly lower in adult Ces1d−/− mice than in adult WT mice, irrespective of CPF treatment (Figure 7D). The reduced expression of Ces1c in Ces1d−/− lung compared to its WT counterpart was not observed under baseline conditions, i.e., in the absence of LPS stimulus (data not shown). On the other hand, Ces2g mRNA, but not Ces1c, was downregulated in adult Ces1d−/− mice by LPS, irrespective of CPF treatment (Figure 7E), which is like that seen in adult WT mice (Figure 7B).

We next determined the levels of surfactant protein (SP) gene expression following repeated low-level CPF exposure in the absence and presence of LPS, because they have not been examined under these conditions and are known to be altered in some respiratory diseases.86-89 Genes that encode the surfactant proteins A (Sftpa1), B (Sftpb), C (Sftpc), and D (Sftpd) were evaluated in WT neonatal and adult male lungs (Figure S8A,B). Although CPF treatment on its own had no effect on these genes, Sftpb and Sftpc levels were slightly but significantly downregulated following LPS challenge in CPF-treated neonatal mice (Figure S8A). In addition, Sftpb was downregulated following LPS challenge in CO-treated adult male mice. Thus, CPF per se had no effect on lung surfactant protein gene expression, although some modest LPS-induced effects were detected.

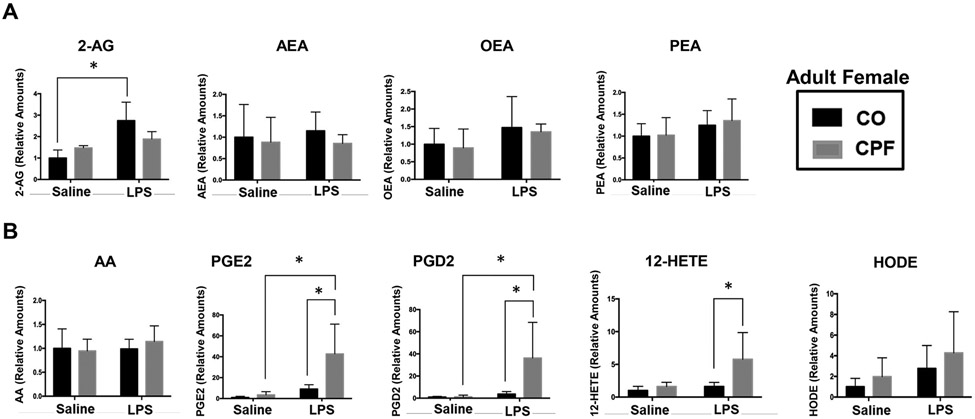

CPF Augmented the Levels of Some LPS-Induced Lipid Mediators in Lung.

Because CPF treatment inactivates Ces isoforms in lung, we were interested in identifying those lipid mediators that changed in abundance. In general, CPF on its own minimally altered lung eCB levels (2-AG, AEA) and N-acylethanolamine levels [oleoylethanolamide (OEA), palmitoylethanolamide (PEA)] in adult females (Figure 8A), neonates (Figure S9A), and adult males (Figure S9B), regardless of the presence of LPS. On the other hand, LPS challenge did increase lung OEA levels in neonates treated with CO vehicle (Figure S9A). In adult males, CPF alone increased arachidonic acid (AA) levels, and LPS increased AEA and OEA levels independent of CPF (Figure S9B). The most striking effects, however, were found in adult female lungs. For example, LPS induced 2-AG levels in CO-treated mice but not in CPF-treated mice (Figure 8A). Moreover, CPF treatment augmented the levels of LPS-stimulated prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), prostaglandin D2 (PGD2), and 12-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (12-HETE) (Figure 8B). In addition, there were minimal differences in the lung lipid profiles between WT and Ces1d−/− mice, irrespective of CPF treatment or exposure to LPS (Figure S9C,D). The only significant difference was that CO-treated Ces1d−/− neonate mice had higher levels of PGD2 than their CO-treated WT counterparts following LPS challenge (Figure S9C). In general, however, the absence of Ces1d did not appear to alter the mouse lung lipid profile.

Figure 8.

Lung lipid mediators were measured by LC-MS/MS. The right superior lung lobe was extracted, and lipid mediators were quantified. Adult female mouse lung extracts were evaluated for eCBs and N-acylethanolamines (A), and eicosanoids (B). Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n=5 mice per condition). A two-way ANOVA and Tukey multiple comparisons test was used to assess significance; *p<0.05 for indicated comparisons. HODE, hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid. Authentic standards of 9-HODE and 13-HODE co-eluted under the chromatographic conditions and exhibit the same selected reaction monitoring value; therefore, the chromatographic peak was defined as ‘HODE’ and likely represents a mixture of regioisomers.

DISCUSSION

CPF is still widely used in agriculture because of its ability to prevent crop damage by insects.1, 2 However, it has been associated with neurotoxic effects in humans and laboratory animals,6-8, 16-18 raising issues about its continued registration with regulatory bodies.90 OP insecticides as a class have also been linked to human immune effects in epidemiological studies,45, 91 but laboratory animal studies that assess the biological plausibility for such effects have been limited. Possible links between OP exposures and development of respiratory illness, chronic bronchitis, airway hypersensitivity, and asthma have also been raised.41-45 Specifically, OPs appear to induce neuronal M2 muscarinic receptor dysfunction and airway hyperreactivity in animal models.9, 46, 47 OP exposure can – by still undefined mechanisms – ‘derepress’ ACh release from postganglionic parasympathetic neurons that synapse onto airway smooth muscle cells, thereby causing their contraction and airway hyperreactivity. Importantly, these effects occur at doses lower than those required to inhibit AChE in lung airways. Here, we examined whether CPF exposures during different life stages could alter subsequent immune responses in the murine lung following LPS challenge. We investigated a mechanism by which CPF might disrupt lung immune homeostasis by utilizing a murine model of LPS-induced inflammation. OPs can inhibit eCB metabolizing enzymes in animal models at dose levels that do not inhibit brain AChE, thereby causing localized increases in eCB levels.16-18, 56, 60 The effects of increased eCB tone on immune functions are known to be complicated; for example, eCBs can either attenuate23, 92 or augment25 the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Here, we identified putative xenobiotic and lipid metabolizing Ces isoforms – Ces1d, Ces1c, and Ces1b – in murine lung at different ages that were partially inactivated following oral CPF exposures, then explored whether their inhibition altered the lung’s immune responses to LPS challenge.

Our CPF treatment regimen could decrease adult lung AChE activity, whereas neonate lung activity was unchanged. However, some caveats regarding the inhibition results are warranted. AChEs in a non-saline perfused mouse lung will come from multiple sources. For example, AChEs are found in the extensive vascular/capillary network in lungs, such as the soluble forms in plasma and membrane-bound forms in RBCs and endothelial cells,93 and in lung parenchyma, such as epithelial cells, fibroblasts, macrophages, and other immune cells. The ‘washed’ lung microsomes we prepared will be free of most contaminating soluble/cytosolic proteins; however, trace amounts of RBC membranes and endothelial membranes will likely contaminate the preparation. Therefore, AChEs from these sources – some of which are probably inhibited by CPO – will likely contribute to the measured lung enzyme activity and its apparent inhibition. Thus, whereas brain AChE activity was not inhibited by CPF, the AChE activity in adult (but not neonate) lung tissue was.

2-AG and AEA hydrolysis activities in lung, liver, brain, and spleen following CPF exposures in neonatal (treatment from PND 10-16) and adult female mice were mostly unaltered. Our data for eCB hydrolysis activities in neonatal mice differ from those in neonatal rats where CPF at 1 mg/kg was shown to disrupt 2-AG and AEA hydrolysis in brain, liver, and spleen,60 thus the mice seem to be more sensitive than rats. We are currently exploring the reasons behind this (Carr et al., unpublished data). CPF exposure also inhibited Ces activities in neonate and adult serum and lung and in adult liver, whereas it slightly induced Ces activity in neonate liver. Ces specific activity in rat and mouse lung is comparatively high relative to other extrahepatic tissues.40, 94 Moreover, Ces isoforms appear to be the dominant serine hydrolases within mouse lung. For example, our ABPP-MS results demonstrated that Ces isoforms accounted for 3 or 4 of the most active serine hydrolases in murine lung from all age groups. Ces isoforms are also more intrinsically sensitive targets of oxon-dependent covalent inhibition than Magl and Faah,11, 95, 96 thereby acting as sentinels that protect these regulatory enzymes. This was corroborated by our study because lung Magl was not inhibited by CPF treatment, whereas Ces1b, Ces1c, and Ces1d were. In vitro experiments using selective chemical inhibitors also showed that Magl was the primary 2-AG hydrolytic enzyme in murine lung, whereas Ces enzymes seemed to play a minor role. Together these findings probably explain why the 2-AG hydrolytic activity in lung microsomes was not altered by in vivo CPF treatment. In addition, although the Faah enzyme was not detectable in lung by ABPP-MS, AEA hydrolysis activity was discernable but it was not altered by CPF treatment. Consistent with these findings, our lipidomic analysis showed that 2-AG and AEA levels in lung were also unchanged by CPF treatments. Thus, the treatment regimen used in this study did not seem to perturb the eCB system in the lung, as was hypothesized. However, LPS challenge on its own did increase adult female lung 2-AG levels.

As the lung matures there is a steady increase in Ces expression,94 thus changes in the expression of individual Ces isoforms during ontogenesis is likely one reason for the age-related difference in sensitivity to OP toxicants. Indeed, our data indicated that Ces enzymes in neonate lung were more sensitive than those in adult lung (Figure 3C). Because Ces isoforms in lung are known to be distributed in different subcellular fractions,97 it is feasible that some Ces isoforms might be inaccessible to the reactive oxon during the maturation process. This could explain the differential sensitivity of Ces1d in neonatal and adult mice toward CPF-dependent inactivation. CPF treatment also did not alter the expression of Ces1d, Ces1c, and Ces2g mRNA in lungs of either neonates or adults. On the other hand, LPS was shown to downregulate Ces2g mRNA levels and its enzymatic activity (based on ABPP-MS data), irrespective of CPF treatment and genotype. This finding is consistent with our previous study in which Ces2g activity in mouse spleen was decreased by LPS treatment.38 Thus, LPS-mediated inflammation seems to reduce the transcription of the Ces2g gene, although the molecular mechanism for this effect is currently unclear.

Ces/CES enzymes have the ability to metabolize 2-AG and other immunomodulatory lipids, such as prostaglandin glyceryl esters (PG-Gs),34, 35, 37, 75 thus their inactivation or overexpression could alter immune responses.98, 99 Although CPF treatment inhibited Ces isoforms in lung (between 40-60% reduction), this did not alter the levels of LPS-induced cytokines and the immunophenotype of lung cells (except for a small increase in the percentage of LPS-induced dendritic cells in female lungs). Furthermore, treatment of Ces1d−/− mice with CPF did not uncover adverse immune responses that were not observed in WT mice, except for one endpoint: CPF augmented Tnfa mRNA levels in lungs of adult Ces1d−/− mice but not WT mice in response to LPS. On the other hand, CPF attenuated LPS-induced Tnfa mRNA levels in neonate lungs irrespective of genotype. Overall, the absence of Ces1d – a putative detoxification enzyme of CPO – did not appear to make the mice more susceptible to CPF-dependent acute toxicity (i.e., brain AChE activities were similar between WT and Ces1d−/− mice) or adverse immune effects following LPS challenge.

The general absence of immune effects in our study is similar to that of a previous study, which reported that a 90-day oral treatment of mice with the OP insecticide ethion also did not alter the levels of LPS-induced cytokines.51 On the other hand, several reports indicated that CPF exposure could lead to altered immune responses in vivo and in vitro. One report indicated that the levels of circulating monocytes and macrophages were altered in a colitis mouse model exposed to CPF.100 In another, rats treated with CPF (5 mg/kg, twice weekly for a period of 28 days) exhibited altered T-lymphocyte blastogenesis in response to concanavalin A, whereas B-lymphocyte blastogenesis in response to LPS was normal.101 Furthermore, in vitro studies had shown that TNF-α levels were increased in guinea pig alveolar macrophages and differentiated human THP-1 cells following exposures to OP compounds alone (in the absence of an immune stimuli).48, 102 Therefore, several reports, using different models, do suggest that CPF exposure can lead to altered immune responses. In our study, however, we assessed lung immune responses at a single time point (6 h) following an LPS challenge, so it is difficult to make head-to-head comparisons of our results with those previous studies.

eCBs, arachidonic acid, and eicosanoids are immunomodulatory lipids with important roles in pro- and anti-inflammatory processes.103-109 The activities of these lipid mediators are tightly regulated by their biosynthesis and degradation. Previous studies have examined the effects of CPF and other OPs on the brain lipidome and demonstrated significant changes in the concentrations of lipid mediators;16, 64, 110 however, our study is the first to our knowledge to examine lipid mediators in the lung following an OP exposure. We found that CPF treatment did not alter the lung profiles of 2-AG, AEA, OEA, and PEA, which is also consistent with the fact that CPF did not alter lung 2-AG and AEA hydrolytic activities. There was, however, a CPF-mediated effect on several lipid mediators following LPS stimulation, including PGE2, PGD2, and 12-HETE, which were shown to be augmented by CPF treatment in adult female lung but not adult male lung. The sex difference for this effect is interesting because it was previously shown that adult female rats were also more sensitive than adult male rats to CPF in an airway hyperreactivity model.111 The significance of increased PGE2 levels is that it might exacerbate LPS-induced inflammation and inflammatory pain.38 The sex difference for these lipid mediators might be related to the Ces1b isoform being inhibited by CPF treatment in female lung but not in male lung (Figure 4); however, more work needs to be done to evaluate this.

Although the CPF dosing regimen that we used (2.5 mg/kg, 7 days) and the assessment of immune effects at a single time point after LPS challenge might have limited us from observing CPF-dependent alterations in lung immunity, an alternative explanation is that Ces isoforms in lung provide an important protective function that prevents CPF-mediated immunotoxic effects because of their ability to neutralize reactive oxons.59, 94, 112 This is supported by the observation that Ces isoforms were the main serine hydrolases inactivated in lung (Figure 4). Studies in guinea pigs and rats also suggested that the lung is an important site for the detoxification of OPs.94, 97 Interestingly, our data indicated Ces1c was inhibited by CPF in mice of all ages. Further, Ces1d was not targeted and inactivated in adult lung, thus Ces1c may be the main protective enzyme that prevents overt CPF-dependent immunotoxic effects, at least in adults. Our data support this hypothesis, because in the setting of LPS-induced inflammation, the augmented production of Tnfa mRNA in adult Ces1d−/− mice following CPF exposure (Figure 6C) seems to parallel the downregulation of Ces1c mRNA in lungs of knockout mice compared to WT mice, irrespective of CPF exposure (Figure 7D). Because less Ces1c is available in the Ces1d−/− lung in the setting of LPS-induced inflammation, the knockout mice might reveal more CPF-mediated immune effects, such as increased Tnfa, than WT mice do.

CONCLUSIONS

This is the first study to identify the Ces isoforms in mouse lung (Ces1c, Ces1d, and Ces1b) that are inactivated following CPF treatment. We demonstrated that subacute, low-level CPF exposure can inhibit pulmonary Ces isoforms in an age-dependent manner. Neonatal mice were more sensitive to this inhibition, with Ces1d, Ces1c, and Ces1b being partially inactivated, whereas inhibition of Ces1d was not observed in adult mice. However, inhibition of Ces enzymes by CPF treatment did not alter the metabolism of eCBs in lung microsomes, but this was not surprising given that Magl is the primary 2-AG hydrolytic enzyme in murine lung and it was not inhibited by CPF in our model. Although Ces enzymes were hypothesized to play a role in immune regulation, their attenuated activities following CPF treatment did not lead to widespread altered lung immune responses to LPS, except for some adult female-dependent increases in dendritic cells and lipid mediator levels. We conclude that CPF exposure can inactivate several Ces isoforms in mouse lung and, in the setting of inflammation, increase certain lipid mediators in a female-dependent manner, suggesting a sex-dependent effect of CPF. However, it can also be concluded that CPF treatment did not lead to widespread altered lung immune effects in response to a subsequent LPS challenge.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Drs. Shirley Guo-Ross and Jim Nichols for their assistance with the animal studies, and Hannah Shaeffer and Juliet Ryan for their technical assistance. We also thank Michelle Salemi at the UC Davis proteomic core facility for advice on sample preparation. Funding was provided by NIH R15GM128206 and the Mississippi State University College of Veterinary Medicine.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Primer sequences used for RT-qPCR analysis; Gating strategy used to identify immune cells in the lung; daily mouse weights during the CPF treatment regimen; AChE activities of brain and lung samples; gel-based ABPP and western blots of neonate and adult lungs; innate and adaptive immunophenotypes in WT and Ces1d−/− mouse lungs determined by flow cytometry; cytokine mRNA and protein levels in WT mouse lungs determined by RT-qPCR and ELISA; cytokine and Ces isoform mRNA levels in mouse pulmonary alveolar macrophages determined by RT-qPCR; lung surfactant protein mRNA levels determined by RT-qPCR; lung lipid mediators quantified by targeted LC-MS/MS analysis

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Costa LG (2018) Organophosphorus Compounds at 80: Some Old and New Issues. Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology, 162, 24–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Grube A, Donaldson D, Kiely T, and Wu L (2011) Pesticides industry sales and usage. US EPA, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Arcury TA, Grzywacz JG, Barr DB, Tapia J, Chen H, and Quandt SA (2007) Pesticide urinary metabolite levels of children in eastern North Carolina farmworker households. Environ Health Perspect, 115, 1254–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Tamaro CM, Smith MN, Workman T, Griffith WC, Thompson B, and Faustman EM (2018) Characterization of organophosphate pesticides in urine and home environment dust in an agricultural community. Biomarkers, 23, 174–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Koch D, Lu C, Fisker-Andersen J, Jolley L, and Fenske RA (2002) Temporal association of children's pesticide exposure and agricultural spraying: report of a longitudinal biological monitoring study. Environ Health Perspect, 110, 829–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Rauh VA, Perera FP, Horton MK, Whyatt RM, Bansal R, Hao X, Liu J, Barr DB, Slotkin TA, and Peterson BS (2012) Brain anomalies in children exposed prenatally to a common organophosphate pesticide. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109, 7871–7876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Rauh V, Arunajadai S, Horton M, Perera F, Hoepner L, Barr DB, and Whyatt R (2011) Seven-year neurodevelopmental scores and prenatal exposure to chlorpyrifos, a common agricultural pesticide. Environ Health Perspect, 119, 1196–1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Rauh VA, Garfinkel R, Perera FP, Andrews HF, Hoepner L, Barr DB, Whitehead R, Tang D, and Whyatt RW (2006) Impact of prenatal chlorpyrifos exposure on neurodevelopment in the first 3 years of life among inner-city children. Pediatrics, 118, e1845–1859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Shaffo FC, Grodzki AC, Fryer AD, and Lein PJ (2018) Mechanisms of organophosphorus pesticide toxicity in the context of airway hyperreactivity and asthma. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol, 315, L485–L501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Hulse EJ, Davies JOJ, Simpson AJ, Sciuto AM, and Eddleston M (2014) Respiratory complications of organophosphorus nerve agent and insecticide poisoning. Implications for respiratory and critical care. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 190, 1342–1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Quistad GB, Liang SN, Fisher KJ, Nomura DK, and Casida JE (2006) Each Lipase Has a Unique Sensitivity Profile for Organophosphorus Inhibitors. Toxicological Sciences, 91, 166–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Quistad GB, Klintenberg R, Caboni P, Liang SN, and Casida JE (2006) Monoacylglycerol lipase inhibition by organophosphorus compounds leads to elevation of brain 2-arachidonoylglycerol and the associated hypomotility in mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol, 211, 78–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Lu HC, and Mackie K (2016) An Introduction to the Endogenous Cannabinoid System. Biol Psychiatry, 79, 516–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Pacher P, Bátkai S, and Kunos G (2006) The endocannabinoid system as an emerging target of pharmacotherapy. Pharmacol Rev, 58, 389–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Crow JA, Bittles V, Herring KL, Borazjani A, Potter PM, and Ross MK (2012) Inhibition of recombinant human carboxylesterase 1 and 2 and monoacylglycerol lipase by chlorpyrifos oxon, paraoxon and methyl paraoxon. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol, 258, 145–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Carr RL, Adams AL, Kepler DR, Ward AB, and Ross MK (2013) Induction of endocannabinoid levels in juvenile rat brain following developmental chlorpyrifos exposure. Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology, 135, 193–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Carr RL, Armstrong NH, Buchanan AT, Eells JB, Mohammed AN, Ross MK, and Nail CA (2017) Decreased anxiety in juvenile rats following exposure to low levels of chlorpyrifos during development. Neurotoxicology, 59, 183–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Carr RL, Graves CA, Mangum LC, Nail CA, and Ross MK (2014) Low level chlorpyrifos exposure increases anandamide accumulation in juvenile rat brain in the absence of brain cholinesterase inhibition. Neurotoxicology, 43, 82–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Carr RL, Alugubelly N, de Leon K, Loyant L, Mohammed AN, Patterson ME, Ross MK, and Rowbotham NE (2020) Inhibition of fatty acid amide hydrolase by chlorpyrifos in juvenile rats results in altered exploratory and social behavior as adolescents. Neurotoxicology, 77, 127–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Turcotte C, Chouinard F, Lefebvre JS, and Flamand N (2015) Regulation of inflammation by cannabinoids, the endocannabinoids 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol and arachidonoyl-ethanolamide, and their metabolites. Journal of leukocyte biology, 97, 1049–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Alhouayek M, Lambert DM, Delzenne NM, Cani PD, and Muccioli GG (2011) Increasing endogenous 2-arachidonoylglycerol levels counteracts colitis and related systemic inflammation. FASEB J, 25, 2711–2721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Gallily R, Breuer A, and Mechoulam R (2000) 2-Arachidonylglycerol, an endogenous cannabinoid, inhibits tumor necrosis factor-alpha production in murine macrophages, and in mice. Eur J Pharmacol, 406, R5–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Rettori E, De Laurentiis A, Zorrilla Zubilete M, Rettori V, and Elverdin JC (2012) Anti-inflammatory effect of the endocannabinoid anandamide in experimental periodontitis and stress in the rat. Neuroimmunomodulation, 19, 293–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Facchinetti F, Del Giudice E, Furegato S, Passarotto M, and Leon A (2003) Cannabinoids ablate release of TNFalpha in rat microglial cells stimulated with lypopolysaccharide. Glia, 41, 161–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Mimura T, Oka S, Koshimoto H, Ueda Y, Watanabe Y, and Sugiura T (2012) Involvement of the endogenous cannabinoid 2 ligand 2-arachidonyl glycerol in allergic inflammation. Int Arch Allergy Immunol, 159, 149–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Mach F, and Steffens S (2008) The role of the endocannabinoid system in atherosclerosis. J Neuroendocrinol, 20 Suppl 1, 53–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Ross MK, Streit TM, and Herring KL (2010) Carboxylesterases: Dual roles in lipid and pesticide metabolism. J Pestic Sci, 35, 257–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Lian J, Nelson R, and Lehner R (2018) Carboxylesterases in lipid metabolism: from mouse to human. Protein & Cell, 9, 178–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Timchalk C, Nolan RJ, Mendrala AL, Dittenber DA, Brzak KA, and Mattsson JL (2002) A Physiologically based pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic (PBPK/PD) model for the organophosphate insecticide chlorpyrifos in rats and humans. Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology, 66, 34–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Ross MK, and Edelmann MJ (2012) Carboxylesterases: A Multifunctional Enzyme Involved in Pesticide and Lipid Metabolism, In Parameters for Pesticide QSAR and PBPK/PD Models for Human Risk Assessment pp 149–164, American Chemical Society. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Holmes RS, Wright MW, Laulederkind SJ, Cox LA, Hosokawa M, Imai T, Ishibashi S, Lehner R, Miyazaki M, Perkins EJ, Potter PM, Redinbo MR, Robert J, Satoh T, Yamashita T, Yan B, Yokoi T, Zechner R, and Maltais LJ (2010) Recommended nomenclature for five mammalian carboxylesterase gene families: human, mouse, and rat genes and proteins. Mamm Genome, 21, 427–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Szafran BN, Lee JH, Borazjani A, Morrison P, Zimmerman G, Andrzejewski KL, Ross MK, and Kaplan BLF (2018) Characterization of Endocannabinoid-Metabolizing Enzymes in Human Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells under Inflammatory Conditions. Molecules, 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Blankman JL, and Cravatt BF (2013) Chemical probes of endocannabinoid metabolism. Pharmacol Rev, 65, 849–871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Xie S, Borazjani A, Hatfield MJ, Edwards CC, Potter PM, and Ross MK (2010) Inactivation of lipid glyceryl ester metabolism in human THP1 monocytes/macrophages by activated organophosphorus insecticides: role of carboxylesterases 1 and 2. Chemical research in toxicology, 23, 1890–1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Wang R, Borazjani A, Matthews AT, Mangum LC, Edelmann MJ, and Ross MK (2013) Identification of palmitoyl protein thioesterase 1 in human THP1 monocytes and macrophages and characterization of unique biochemical activities for this enzyme. Biochemistry, 52, 7559–7574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Grabner GF, Zimmermann R, Schicho R, and Taschler U (2017) Monoglyceride lipase as a drug target: At the crossroads of arachidonic acid metabolism and endocannabinoid signaling. Pharmacol Ther, 175, 35–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Scheaffer HL, Borazjani A, Szafran BN, and Ross MK (2020) Inactivation of CES1 Blocks Prostaglandin D2 Glyceryl Ester Catabolism in Monocytes/Macrophages and Enhances Its Anti-inflammatory Effects, Whereas the Pro-inflammatory Effects of Prostaglandin E2 Glyceryl Ester Are Attenuated. ACS Omega. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Szafran B, Borazjani A, Lee JH, Ross MK, and Kaplan BL (2015) Lipopolysaccharide suppresses carboxylesterase 2g activity and 2-arachidonoylglycerol hydrolysis: A possible mechanism to regulate inflammation. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat, 121, 199–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Jones RD, Taylor AM, Tong EY, and Repa JJ (2013) Carboxylesterases are uniquely expressed among tissues and regulated by nuclear hormone receptors in the mouse. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals, 41, 40–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Imamura T, Schiller NL, and Fukuto TR (1983) Malathion and phenthoate carboxylesterase activities in pulmonary alveolar macrophages as indicators of lung injury. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 70, 140–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Doust E, Ayres JG, Devereux G, Dick F, Crawford JO, Cowie H, and Dixon K (2014) Is pesticide exposure a cause of obstructive airways disease? European Respiratory Review, 23, 180–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Hernandez AF, Parron T, and Alarcon R (2011) Pesticides and asthma. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol, 11, 90–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Mamane A, Raherison C, Tessier JF, Baldi I, and Bouvier G (2015) Environmental exposure to pesticides and respiratory health. Eur Respir Rev, 24, 462–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Gascon M, Morales E, Sunyer J, and Vrijheid M (2013) Effects of persistent organic pollutants on the developing respiratory and immune systems: A systematic review. Environment International, 52, 51–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Ye M, Beach J, Martin JW, and Senthilselvan A (2013) Occupational pesticide exposures and respiratory health. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 10, 6442–6471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Fryer AD, Lein PJ, Howard AS, Yost BL, Beckles RA, and Jett DA (2004) Mechanisms of organophosphate insecticide-induced airway hyperreactivity. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol, 286, L963–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Lein PJ, and Fryer AD (2005) Organophosphorus insecticides induce airway hyperreactivity by decreasing neuronal M2 muscarinic receptor function independent of acetylcholinesterase inhibition. Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology, 83, 166–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Proskocil BJ, Grodzki ACG, Jacoby DB, Lein PJ, and Fryer AD (2019) Organophosphorus Pesticides Induce Cytokine Release from Differentiated Human THP1 Cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol, 61, 620–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Haddad EB, Rousell J, Lindsay MA, and Barnes PJ (1996) Synergy between tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin 1beta in inducing transcriptional down-regulation of muscarinic M2 receptor gene expression. Involvement of protein kinase A and ceramide pathways. J Biol Chem, 271, 32586–32592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Nie Z, Jacoby DB, and Fryer AD (2009) Etanercept prevents airway hyperresponsiveness by protecting neuronal M2 muscarinic receptors in antigen-challenged guinea pigs. Br J Pharmacol, 156, 201–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Verma G, Mukhopadhyay CS, Verma R, Singh B, and Sethi RS (2019) Long-term exposures to ethion and endotoxin cause lung inflammation and induce genotoxicity in mice. Cell and Tissue Research, 375, 493–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Watanabe W, Yoshida H, Hirose A, Akashi T, Takeshita T, Kuroki N, Shibata A, Hongo S, Hashiguchi S, Konno K, and Kurokawa M (2013) Perinatal Exposure to Insecticide Methamidophos Suppressed Production of Proinflammatory Cytokines Responding to Virus Infection in Lung Tissues in Mice. BioMed research international, 2013, 151807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Ghosh S (2000) Cholesteryl ester hydrolase in human monocyte/macrophage: cloning, sequencing, and expression of full-length cDNA. Physiological genomics, 2, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Szafran B, Borazjani A, Carr RL, Ross MK, Kaplan BLF (2021) Carboxylesterase Inactivation by Chlorpyrifos: Immunotoxic or Protective in the Murine Lung?, In 2021 Society of Toxicology Annual Meeting, The Toxicologist Abstract #3110, Virtual meeting. [Google Scholar]

- (55).Wei E, Ben Ali Y, Lyon J, Wang H, Nelson R, Dolinsky VW, Dyck JR, Mitchell G, Korbutt GS, and Lehner R (2010) Loss of TGH/Ces3 in mice decreases blood lipids, improves glucose tolerance, and increases energy expenditure. Cell metabolism, 11, 183–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Howell GE 3rd, Kondakala S, Holdridge J, Lee JH, and Ross MK (2018) Inhibition of cholinergic and non-cholinergic targets following subacute exposure to chlorpyrifos in normal and high fat fed male C57BL/6J mice. Food Chem Toxicol, 118, 821–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Ricceri L, Markina N, Valanzano A, Fortuna S, Cometa MF, Meneguz A, and Calamandrei G (2003) Developmental exposure to chlorpyrifos alters reactivity to environmental and social cues in adolescent mice. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 191, 189–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Ricceri L, Venerosi A, Capone F, Cometa MF, Lorenzini P, Fortuna S, and Calamandrei G (2006) Developmental Neurotoxicity of Organophosphorous Pesticides: Fetal and Neonatal Exposure to Chlorpyrifos Alters Sex-Specific Behaviors at Adulthood in Mice. Toxicological Sciences, 93, 105–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]