Abstract

A pleiotropic mutant of Paracoccus denitrificans, which has a severe defect that affects its anaerobic growth when either nitrate, nitrite, or nitrous oxide is used as the terminal electron acceptor and which is also unable to use ethanolamine as a carbon and energy source for aerobic growth, was isolated. This phenotype of the mutant is expressed only during growth on minimal media and can be reversed by addition of cobalamin (vitamin B12) or cobinamide to the media or by growth on rich media. Sequence analysis revealed the mutation causing this phenotype to be in a gene homologous to cobK of Pseudomonas denitrificans, which encodes precorrin-6x reductase of the cobalamin biosynthesis pathway. Convergently transcribed with cobK is a gene homologous to cobJ of Pseudomonas denitrificans, which encodes precorrin-3b methyltransferase. The inability of the cobalamin auxotroph to grow aerobically on ethanolamine implies that wild-type P. denitrificans (which can grow on ethanolamine) expresses a cobalamin-dependent ethanolamine ammonia lyase and that this organism synthesizes cobalamin under both aerobic and anaerobic growth conditions. Comparison of the cobK and cobJ genes with their orthologues suggests that P. denitrificans uses the aerobic pathway for cobalamin synthesis. It is paradoxical that under anaerobic growth conditions, P. denitrificans appears to use the aerobic (oxygen-requiring) pathway for cobalamin synthesis. Anaerobic growth of the cobalamin auxotroph could be restored by the addition of deoxyribonucleosides to minimal media. These observations provide evidence that P. denitrificans expresses a cobalamin-dependent ribonucleotide reductase, which is essential for growth only under anaerobic conditions.

Denitrification is the dissimilatory reduction of nitrate and nitrite to gaseous products (NO, N2O, and N2), during which the N-oxyanions and N-oxides are used as the terminal electron acceptors for anaerobic respiration (1, 32). The membrane-associated nitrate and NO reductases and the periplasmic nitrite and N2O reductases which are required for the sequential reduction of nitrate to N2 have all been purified from cultures of Paracoccus denitrificans, one of several organisms for which denitrification is well understood (1). P. denitrificans can also use oxygen as a terminal electron acceptor, and the transcription of genes required for denitrification is activated under anoxic growth conditions (32). Transcription factors designated FnrP and Nnr, which are required for the activation of some of the denitrification genes in P. denitrificans, have recently been characterized (33). P. denitrificans also expresses a soluble periplasmic nitrate reductase which can catalyze nitrate reduction in the presence of oxygen and may have a role in redox balancing (1).

As part of an effort to identify other genes involved in the regulation of denitrification, mutants with pleiotropic defects in the ability to utilize N-oxyanions and N-oxides as electron acceptors for anaerobic growth were sought. One such mutant, whose anaerobic growth is severely impaired when nitrate, nitrite, or N2O is used as an electron acceptor, was unexpectedly discovered to have a mutation in a cobalamin (vitamin B12) biosynthesis gene. Analysis of this mutant provided evidence that P. denitrificans expresses a cobalamin-dependent ribonucleotide reductase, which is required for growth only under anaerobic conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids, and growth media.

The strain of P. denitrificans used was Pd1222, a restriction-deficient mutant which shows increased frequencies of conjugation and is therefore well suited for genetic analysis (9). The strains of Escherichia coli used were as follows: S17-1 (thi pro hsdR recA integrated RP4-2 Tc::Mu Km::Tn7) as the donor strain for transposon mutagenesis (29), JM83 (ara Δ[lac-proAB] rpsL φ80lacZΔM15) for the routine propagation of plasmid DNA, and JRG13 (metE) (from J. R. Guest). The vector used for construction of the P. denitrificans genomic library was pLAFR3, as described previously (6). Other plasmids used were the broad-host-range cloning vector pRK415 (17), the broad-host-range promoter probe vector pMP220 (31), the suicide vector pSUP202 (29), pUC18 and pLITMUS28 for the subcloning of DNA fragments, and pSUP2021 for the delivery of Tn5 (29). The rich medium used for growth of E. coli and P. denitrificans was L broth (tryptone [10 g liter−1], yeast extract [5 g liter−1], NaCl [5 g liter−1]). The defined medium for P. denitrificans was that described by Harms et al. (11), supplemented with 1 μg of cobalamin or cobinamide ml−1 as required.

Mutant isolation.

For transposon mutagenesis, 50-ml cultures of exponentially growing E. coli S17-1(pSUP2021) and 50-ml stationary-phase cultures of P. denitrificans (both in L broth, with 100 μg of ampicillin ml−1 for the E. coli culture) were harvested and resuspended in a minimal volume of L broth. The E. coli culture was washed three times in a small volume of L broth to remove traces of ampicillin. The two cell suspensions were mixed and dispensed onto a sterile 0.45-μm-pore-size nitrocellulose filter on the surface of L agar in a petri dish, which was then incubated overnight at 30°C. Bacteria were washed off the filter into 1 ml of L broth. Serial dilutions in L broth were made, and aliquots were plated onto L broth containing rifampin (100 μg ml−1) (to select against the E. coli donor) and kanamycin (100 μg ml−1) (to select P. denitrificans exconjugants which had acquired a copy of Tn5). Chlorate-resistant mutants were isolated by the method of Zumft et al. (35), which involved incubating the plates anaerobically for 2 days to kill the chlorate-sensitive cells, followed by overnight growth under aerobic conditions to rescue the chlorate-resistant survivors. Chlorate-resistant mutants were purified for further characterization. For mutagenesis with the Ω interposon (21), S17-1 transformed with a pSUP202 derivative containing P. denitrificans DNA disrupted with the Ω interposon was conjugated with P. denitrificans Pd1222 as described above, and exconjugants were selected on L agar containing rifampin (100 μg ml−1) and streptomycin (100 μg ml−1). Fifty exconjugants were grown as patches on nitrocellulose filters on the surface of L agar for analysis by colony hybridization, which was done according to the method of Sambrook et al. (25), to identify exconjugants which had acquired the Ω interposon by a double crossover. Candidates were further analyzed by the isolation of genomic DNA (using the Wizard genomic DNA purification system; Promega) and hybridization analysis.

DNA manipulation and sequencing.

All routine DNA methods and Southern transfer and hybridization procedures were performed as described by Sambrook et al. (25). For DNA sequence analysis, subclones of pSAD17 were isolated in pUC18 and sequences were determined with the vector universal and reverse primers. Sequencing was completed with synthetic oligonucleotides designed on the basis of the partial sequence. The 2-kb PstI-SphI fragment of pSAD17 was fully sequenced on both strands.

Construction of lacZ fusions and β-galactosidase assays.

To construct a cobL-lacZ fusion, the 700-bp SphI-BamHI fragment containing the 5′ ends of cobL and cobK (Fig. 1) was first cloned into pUC18. The fragment was then excised with SphI and KpnI and was cloned into pMP220, such that the putative cobL promoter was oriented to drive the transcription of lacZ. To construct a cobK-lacZ fusion, the same 700-bp fragment was excised from the pUC18 clone with BamHI and HindIII and was cloned into pLITMUS28. The fragment was then excised from pLITMUS28 with XbaI and PstI and was cloned into the corresponding sites in pMP220 to orient the putative cobK promoter with lacZ. Plasmids derived from pMP220 were introduced into P. denitrificans by conjugation with E. coli S17-1, as described above. For β-galactosidase assays, cultures were grown aerobically and anaerobically in defined media (supplemented with 1 μg of cobalamin ml−1 as required). Samples were taken during log phase, cells were disrupted with chloroform-sodium dodecyl sulfate, and β-galactosidase was assayed (19).

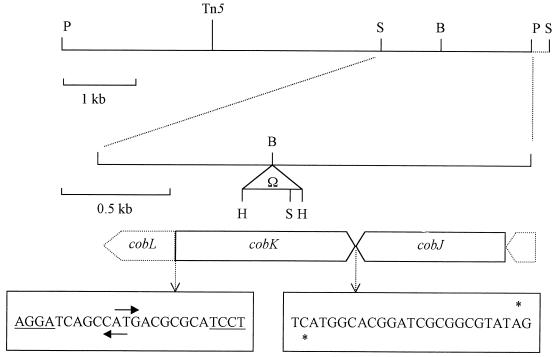

FIG. 1.

Map of a part of the cob locus of P. denitrificans. The approximate location of the original Tn5 insertion in the 9.6-kb PstI fragment that complements the Tn5 insertion mutant is indicated. The 2-kb PstI-SphI fragment that was sequenced is shown in expanded form, including the site of the Ω insertion (not to scale). Abbreviations: P, PstI; H, HindIII; B, BamHI; S, SphI. Nucleotide sequences from the regions where genes overlap are shown; start codons are indicated by arrows, stop codons are indicated by asterisks, and potential ribosome binding sites are underlined.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The DNA sequence has been deposited in the EMBL database under the accession no. AJ242870.

RESULTS

Mutant isolation and preliminary characterization.

Resistance to chlorate was used as a preliminary screen to identify mutants unable to express the respiratory membrane-bound nitrate reductase (35). P. denitrificans was subjected to random mutagenesis with the transposon Tn5, and approximately 300 chlorate-resistant mutants were isolated. It was confirmed that all of these mutants were unable to grow anaerobically by utilizing nitrate as an electron acceptor, and they were then screened for the ability to utilize nitrite. One mutant which was unable to grow on either nitrate or nitrite in the absence of oxygen but grew normally in the presence of oxygen was identified. Genomic DNA from this strain, designated AH6, was probed with Tn5, which revealed that it had acquired a single copy of the transposon. Surprisingly, it was discovered that AH6 denitrifies normally on rich media, such as L broth or brain heart infusion, both supplemented with nitrate, and expresses its mutant phenotype only on defined media. By making additions to defined media, it was found that this effect could be ascribed to cobalamin: AH6 grew anaerobically on minimal media with nitrate or nitrite, provided that cobalamin was provided exogenously. A similar effect was achieved by the addition of cobinamide, an intermediate in cobalamin biosynthesis. This suggests that the primary defect of AH6 is an inability to synthesize cobalamin and that the mutation is in a gene involved in part I of the cobalamin pathway, which is responsible for cobinamide biosynthesis (24). The cobalamin auxotrophy of AH6 was confirmed by showing that, unlike its parent, Pd1222, AH6 was unable to utilize ethanolamine as a carbon source for aerobic growth unless it was provided with exogenous cobalamin. This indicates that P. denitrificans expresses a cobalamin-dependent ethanolamine ammonia lyase (as does Salmonella typhimurium) (5), which is inactive in AH6 due to its inability to synthesize cobalamin; this also suggests that P. denitrificans synthesizes cobalamin under both aerobic and anaerobic growth conditions.

Complementation of AH6.

A genomic library of P. denitrificans in the broad-host-range vector pLAFR3 (6) was introduced into AH6 by conjugation, and six exconjugants capable of anaerobic growth on nitrate were independently isolated. The six cosmids isolated from these exconjugants shared a 9.6-kb PstI fragment, which was subcloned into the broad-host-range vector pRK415 to generate a plasmid designated pSAD17. The introduction of pSAD17 into AH6 also restored its ability to grow on nitrate and nitrite. A partial restriction fragment of the 9.6-kb PstI fragment is shown in Fig. 1; this figure also shows the approximate location of the Tn5 insertion in the equivalent region of the chromosome of AH6, which was determined by hybridization analysis. Three regions of the PstI fragment were sequenced on one strand only, and translations of those sequences showed significant similarity to the products of the cobK, cobJ, and cobF genes of Pseudomonas denitrificans, which are involved in part I of the cobalamin biosynthesis pathway. Thus, it appears that the Tn5 insertion in AH6 is in a region of the chromosome that contains a cluster of cobinamide biosynthesis genes.

Gene disruption in the cob region.

The fact that all of the phenotypes of AH6 can be reversed by the addition of cobalamin or cobinamide to growth media and the results of the hybridization analysis suggested that the single transposon insert in AH6 is responsible for all of its defects. Nevertheless, the possibility that there are multiple mutations in AH6, could not be excluded, especially since chlorate is a known mutagen (22). Thus, the same region of the chromosome in the wild-type strain, Pd1222, was mutated with the Ω interposon, which contains genes for resistance to streptomycin and spectinomycin and transcriptional terminators at both ends (21). Approximately 2 kb from the right end of the PstI fragment (right of the SphI site) which complements AH6 were cloned into the suicide vector pSUP202, and the Ω interposon was inserted into the BamHI site (Fig. 1). This construct was introduced into Pd1222 by conjugation, and five exconjugants which were thought to have acquired Ω alone by a double crossover (since they were hybridization negative with pSUP202) were identified and cultured for further analysis. One such strain, designated NS52, was chosen for all further work since hybridization analysis of its genomic DNA indicated that NS52 had acquired the Ω interposon at the expected location by a double crossover event. Genomic DNA from NS52 was digested with SphI and was probed with the 2-kb SphI-PstI fragment from pSAD17 (Fig. 1). Fragments of approximately 2.4 and 1.8 kb hybridized (data not shown), which was as predicted from the map shown in Fig. 1, given that there is an SphI site 0.3 kb from the right end of Ω. When digested with SphI and HindIII, 0.7- and 1.5-kb fragments of NS52 DNA hybridized with the probe (data not shown), which is also consistent with the pattern predicted for the insertion of Ω at the BamHI site. Thus, it was concluded that NS52 had acquired the Ω interposon through a double crossover event.

It was found that NS52 has a pleiotropic phenotype similar to that of AH6: the inability to utilize nitrate and nitrite as electron acceptors and the inability to grow on ethanolamine unless supplied with exogenous cobalamin or cobinamide. One difference between AH6 and NS52 was, however, noted; the latter is sensitive to chlorate during anaerobic growth with nitrate (on rich media) whereas AH6 is chlorate resistant under these conditions (AH6 was initially isolated as a chlorate-resistant mutant). The most likely explanation for this difference between the strains is that AH6 has a secondary mutation which renders it resistant to chlorate (for example, a mutation that inactivates the membrane-bound nitrate reductase). For this reason, all subsequent work was done with NS52.

Analysis of the P. denitrificans cobJ and cobK genes.

To confirm the presence of cobalamin biosynthesis genes in pSAD17, the nucleotide sequence of the 2-kb PstI-SphI fragment, into which the Ω interposon was inserted to construct NS52, was determined. Comparison with sequences present in the databases revealed this fragment to contain a homologue of the cobK gene, which encodes precorrin-6x reductase in Pseudomonas denitrificans (2). As is also the case for Pseudomonas denitrificans, downstream of cobK and transcribed convergently with it is the cobJ gene, which encodes precorrin-3b methyltransferase (Fig. 1). Upstream of cobK and divergently oriented is the 5′ end of the cobL gene, the product of which catalyzes the conversion of precorrin-6y to precorrin-8x in Pseudomonas denitrificans (3). The gene organization in this region is rather unusual (Fig. 1). The coding regions of the divergent cobL and cobK genes overlap; the most likely start codon for cobK (as judged by the quality of its predicted ribosome binding site) overlaps with the start codon of cobL. There is a similar situation in Pseudomonas denitrificans, in which the coding frames of cobL and cobK overlap by 10 codons (2). In both organisms, the convergent cobK and cobJ reading frames overlap.

The cobK and cobL promoters.

The gene organization suggests that the cobK gene is not cotranscribed with other genes, so there should be a promoter upstream of cobK and probably also upstream of cobL. To test this possibility, the 700-bp SphI-BamHI fragment of pSAD17 was cloned into the broad-host-range promoter probe vector pMP220, in both orientations, to construct cobK-lacZ and cobJ-lacZ transcriptional fusions. These constructs were introduced into Pd1222 and NS52, and β-galactosidase activities following aerobic and anaerobic growth in the presence and absence of cobalamin were measured (Table 1). The putative cobK promoter showed a significant activity which was unaffected by cobalamin or the cobK mutation but was increased approximately twofold following anaerobic growth (Table 1). The putative cobL promoter showed a weaker but significant activity which increased only slightly under anaerobic growth conditions and was unaffected by the presence of cobalamin or the cobK mutation.

TABLE 1.

β-Galactosidase activities directed by cobK-lacZ and cobL-lacZ fusions in Pd1222 and NS52a

| Fusion | β-Galactosidase activity ina:

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pd1222

|

NS52

|

||||||

| Aerobic

|

Anaerobic

|

Aerobic, − | Anaerobicb

|

||||

| − | + | − | + | − | + | ||

| cobK-lacZ | 172 | 171 | 341 | 338 | 150 | 373 | 405 |

| cobL-lacZ | 81 | 81 | 105 | 107 | 70 | 95 | 97 |

| None (pMP220 alone) | 7 | ND | 8 | ND | 8 | 8 | ND |

Activities are the means of at least six determinations of independently grown cultures in the presence (+) or absence (−) of cobalamin, and they did not differ by more than 10%. ND, not done. Units of activity are as defined by Miller (19).

Activities in the low biomass of NS52 that develops during anaerobic growth were measured.

Features of the cobK and cobJ gene products.

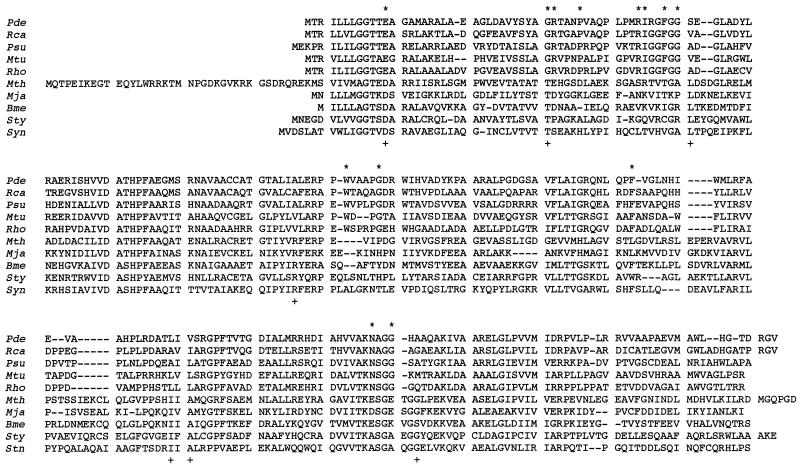

The cobK gene product of P. denitrificans is very likely to be precorrin-6x reductase since it has 45% amino acid sequence identity with the cobK product of Pseudomonas denitrificans (Fig. 2) (2). The cobK gene is also closely related to the cobK gene of Rhodococcus sp. strain NI86/21 (8) and to predicted cobK genes from the genomes of Rhodobacter capsulatus and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Fig. 2). These organisms are facultatively or obligately aerobic and are likely to synthesize cobalamin by the aerobic pathway that has been well characterized for Pseudomonas denitrificans. A phylogenetic analysis (not shown) and sequence alignment (Fig. 2) indicate that P. denitrificans CobK is more distantly related to a distinct group of precorrin-6x reductase sequences from Methanobacterium thermautotrophicum, Methanococcus jannaschii, Bacillus megaterium (product of the cbiJ gene), S. typhimurium (product of the cbiJ gene), and Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803 (Fig. 2). It has been suggested that M. jannaschii, B. megaterium, S. typhimurium, and Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803 synthesize cobalamin by the anaerobic pathway, which does not require oxygen at the ring contraction step (23), and it is likely that the obligately anaerobic M. thermautotrophicum does also.

FIG. 2.

Alignment of CobK (precorrin-6x reductase) of P. denitrificans (Pde) with its orthologues from R. capsulatus (Rca [34]), Pseudomonas denitrificans (Psu [2]), M. tuberculosis (Mtu) (EMBL accession no. Q10680), and Rhodococcus sp. strain NI86/21 (Rho [8]). Included in the alignment are more distantly related precorrin-6x reductases from M. thermautotrophicum (Mth [30]), M. jannaschii (Mja [4]), B. megaterium (Bme [23]), S. typhimurium (Sty [24]), and Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803 (Syn [16]), organisms which utilize the anaerobic pathway for cobalamin synthesis (23). Residues conserved only in enzymes from the aerobic pathway and only in enzymes from the anaerobic pathway are highlighted above (∗) and below (+) the alignment, respectively. Dashes indicate gaps introduced for alignment.

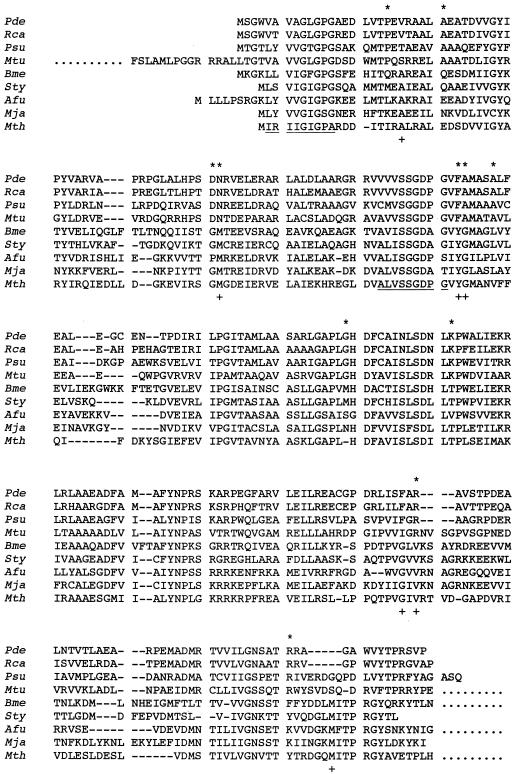

The cobJ product of P. denitrificans is 51% identical to the cobJ product of Pseudomonas denitrificans and can therefore be predicted to be S-adenosylmethionine (SAM)-dependent precorrin-3b methyltransferase (Fig. 3). This assignment is further supported by the presence of SAM-binding motifs in CobJ (Fig. 3) (15). The cobJ gene is also related to predicted cobJ genes which have been found in the genomes of R. capsulatus, M. tuberculosis, Archaeoglobus fulgidus, M. jannaschii, and M. thermautotrophicum and to the cbiH genes of S. typhimurium and B. megaterium, which also encode precorrin-3b methyltransferase (Fig. 3). Phylogenetic analysis of the CobJ sequence alignment (not shown) and examination of the alignment reveal that the proteins cluster into two distinct groups; those from P. denitrificans, R. capsulatus, Pseudomonas denitrificans, and M. tuberculosis fall into a closely related group. These organisms are all facultative anaerobes; Pseudomonas denitrificans synthesizes cobalamin by the aerobic pathway. The remaining CobJ sequences, from B. megaterium, A. fulgidus, M. jannaschii, M. thermautotrophicum, and S. typhimurium, fall into a distinct cluster. S. typhimurium and B. megaterium synthesize cobalamin by the anaerobic pathway (23), which may also be the case for the three obligately anaerobic members of Archaea.

FIG. 3.

Alignment of CobJ (precorrin-3b methyltransferase) of P. denitrificans (Pde) with its orthologues from R. capsulatus (Rca [34]), Pseudomonas denitrificans (Psu [7]), and M. tuberculosis (Mtu) (SWISS-PROT accession no. Q10677). The M. tuberculosis sequence is the C-terminal portion of a fusion to precorrin-2 methyltransferase. Also in the alignment are more distantly related precorrin-3b methyltransferases from B. megaterium (Bme [23]), A. fulgidus (Afu [18]), M. jannaschii (Mja [4]), S. typhimurium (Sty [24]), and M. thermautotrophicum (Mth [30]). The A. fulgidus sequence is the N-terminal portion of a fusion to precorrin-8x methyltransferase. The M. thermautotrophicum protein has an additional 112 residues at its C terminus which are not shown. Residues conserved only in enzymes from the aerobic pathway and only in enzymes from the anaerobic pathway are highlighted above (∗) and below (+) the alignment, respectively. Regions corresponding to motifs I and III of SAM-dependent methyltransferases, as defined by Kagan and Clarke (15), are underlined. Dashes indicate gaps introduced for alignment.

Thus, CobK and CobJ orthologues both fall into two distinct families; the grouping probably reflects whether the enzymes are part of an aerobic or anaerobic cobalamin biosynthesis pathway. The CobK and CobJ alignments reveal several residues conserved within the aerobic and anaerobic groups, but not between them (Fig. 2 and 3). This may reflect the necessity of binding slightly different substrates, since the anaerobic enzymes act on cobalt-containing intermediates, whereas cobalt is inserted at a later stage in the aerobic pathway (27).

Characterization of the cobalamin auxotroph.

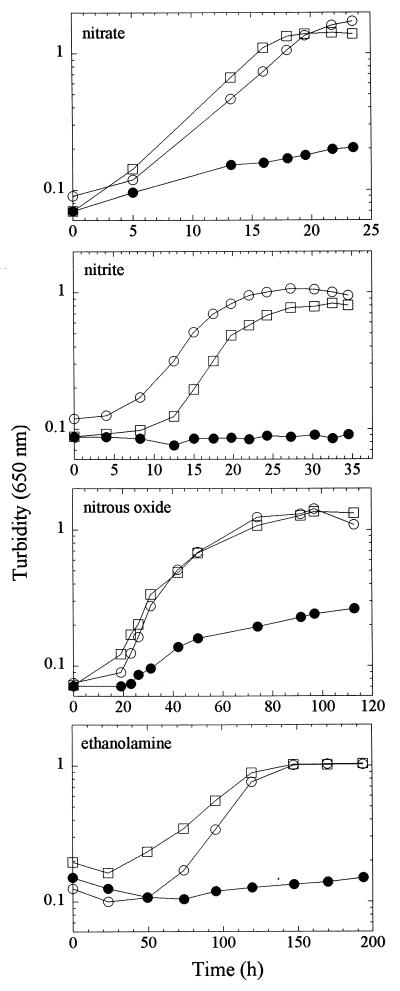

The mutation made within the predicted cobK gene resulted in a pleiotropic phenotype of NS52 that can be reversed by the addition of cobalamin to growth media. Like AH6, NS52 has a pleiotropic defect in anaerobic growth and is unable to grow aerobically on ethanolamine in the absence of cobalamin (Fig. 4). This, combined with the fact that cobK is probably transcribed as a monocistronic mRNA, indicates that the phenotype of NS52 is a direct result of the insertion of Ω into cobK rather than a polar effect on a downstream gene unrelated to cobalamin biosynthesis. The wild-type strain P. denitrificans Pd1222 and the cob mutant NS52 were cultured anaerobically on defined media containing either nitrate, nitrite, or nitrous oxide. The anaerobic growth of NS52 in the presence of all three electron acceptors was severely impaired, with final culture densities being less than 30% of those of the wild-type strain in all cases (Fig. 4). In cultures of NS52 grown under microaerobic conditions, the activation of transcriptional lac fusions to the nir and nor promoters at wild-type levels could be detected. Further, in cultures of NS52 growing poorly under microaerobic conditions, significant activities of nitrate reductase and nitrite reductase could also be detected (data not shown). These observations exclude the possibility that a defect in the expression or activity of the enzymes of denitrification is responsible for the phenotype of NS52. An alternative possibility is that P. denitrificans expresses a cobalamin-dependent ribonucleotide reductase which is required for growth only under anaerobic conditions (since NS52 grows normally aerobically, except on ethanolamine). This was tested by plating dilutions of NS52 cultures onto solid minimal medium supplemented with deoxyribonucleosides. Addition of all four deoxyribonucleosides restored anaerobic growth to NS52 (implying that P. denitrificans is capable of transporting deoxyribonucleosides). This is most easily explained by postulating the existence of an anaerobically inducible cobalamin-dependent ribonucleotide reductase in P. denitrificans, which is consistent with a previous report (10). It is possible that the restoration of the growth of NS52 by the deoxyribonucleosides was due to contaminating traces of cobalamin. This possibility was excluded by demonstrating that the deoxyribonucleoside preparation failed to restore growth to a metE mutant of E. coli that requires either cobalamin or methionine (since it lacks the cobalamin-independent methionine synthase). The aerobic growth of P. denitrificans and the residual anaerobic growth of NS52 must presumably require an alternative cobalamin-independent ribonucleotide reductase. This was confirmed by demonstrating that the residual anaerobic growth of NS52 can be abolished by the addition of hydroxyurea to growth media; hydroxyurea is an inhibitor of the cobalamin-independent ribonucleotide reductases (13).

FIG. 4.

Growth of Pd1222 and the cobalamin auxotroph NS52. Cultures of Pd1222 (open circles), NS52 (filled circles), and NS52 supplemented with cobalamin (squares) were grown anaerobically on succinate with either nitrate (50 mM), nitrite, or nitrous oxide as the terminal electron acceptor or aerobically with ethanolamine as the sole carbon and energy source. For growth on nitrite, the starting concentration was 3 mM and nitrite concentrations in the culture supernatants were monitored during growth. Periodic additions of nitrite were made to maintain the concentration at approximately 3 mM. For growth on nitrous oxide, bottles filled with media were sparged with N2O prior to inoculation and again at approximately 24-h intervals thereafter.

DISCUSSION

The defect in the anaerobic growth of the cobalamin auxotroph of P. denitrificans is very likely due to the requirement for a cobalamin-dependent ribonucleotide reductase under anaerobic growth conditions. This contrasts with the situation of the closely related organism R. capsulatus; cobalamin auxotrophs have a growth defect under microaerobic conditions because they are impaired in the ability to synthesize photopigments (20). The promoter of a cobalamin biosynthesis gene from R. capsulatus (in a translational fusion) has been shown to be insensitive to oxygen and cobalamin (20), unlike the P. denitrificans cobK promoter, which is shown here to be enhanced under anaerobic conditions. P. denitrificans evidently makes cobalamin by the aerobic pathway, which requires molecular oxygen. In Pseudomonas denitrificans, which also uses the aerobic pathway, the conversion of precorrin-3 to the ring-contracted intermediate precorrin-4 requires an oxygen-dependent monooxygenase encoded by cobG (28). It is, therefore, something of a paradox that P. denitrificans appears to utilize the aerobic pathway to make cobalamin under anaerobic growth conditions. Perhaps P. denitrificans has a chimeric pathway and uses an anaerobic-type enzyme to catalyze ring contraction (equivalent to CbiH of S. typhimurium [26]). Further biochemical and genetic characterizations of the P. denitrificans pathway would be required to resolve this issue.

Ribonucleotide reductases fall into three classes (13). The class I enzyme requires oxygen for the formation of a tyrosyl radical and is found in aerobic bacteria and eukaryotes. The class II enzyme utilizes cobalamin, does not require oxygen, and is found in aerobes and anaerobes. The class III enzyme uses a glycyl radical-based mechanism involving SAM and an iron-sulfur cluster and is found in facultative and strict anaerobes. Among the domains Bacteria and Archaea, the cobalamin-dependent (class II) ribonucleotide reductase is widespread (13). Deinococcus radiodurans and M. tuberculosis are reported to have a class I enzyme in addition to the cobalamin-dependent ribonucleotide reductase (13). There is also evidence that Propionibacterium freudenreichii has a second oxygen-requiring ribonucleotide reductase in addition to the cobalamin-dependent enzyme (12). Recently, it has been shown that several Pseudomonas species express both class I and class II enzymes and also have the genes for a class III ribonucleotide reductase (14). Thus, it is common for prokaryotes to express more than one type of ribonucleotide reductase. P. denitrificans must also contain a second ribonucleotide reductase to serve the organism’s needs during aerobic growth, when the cobalamin-dependent enzyme is apparently dispensable. P. denitrificans is thus one of several organisms which express both cobalamin-dependent and -independent ribonucleotide reductases. This work indicates that the cobalamin-dependent enzyme is essential for growth under anaerobic conditions but dispensable under aerobic growth conditions, during which a cobalamin-independent enzyme must be functional.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Lynda Flegg for technical assistance, to Heidi Jillings for contributing to the construction of the lac fusions, and to D. J. Kelly, A. W. B. Johnston, and J. R. Guest for gifts of strains and plasmids.

This work was supported by the United Kingdom BBSRC through the provision of research studentships to A.P.H. and N.S.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berks B C, Ferguson S J, Moir J W B, Richardson D J. Enzymes and associated electron transport systems that catalyse the respiratory reduction of nitrogen oxides and oxyanions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1232:97–173. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(95)00092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanche F, Thibaut D, Famechon A, Debussche L, Cameron B, Crouzet J. Precorrin-6x reductase from Pseudomonas denitrificans: purification and characterization of the enzyme and identification of the structural gene. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1036–1042. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.3.1036-1042.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blanche F, Famechon A, Thibaut D, Debussche L, Cameron B, Crouzet J. Biosynthesis of vitamin B12 in Pseudomonas denitrificans: the biosynthetic sequence from precorrin-6y to precorrin-8x is catalyzed by the cobL gene product. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1050–1052. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.3.1050-1052.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bult C J, White O, Olsen G J, Zhou L, Fleischmann R D, Sutton G G, Blake J A, Fitzgerald L M, Clayton R A, Gocayne J D, Kerlavage A R, Dougherty B A, Tomb J-F, Adams M D, Reich C I, Overbeek R, Kirkness E F, Weinstock K G, Merrick J M, Glodek A, Scott J L, Geoghagen N S M, Weidman J F, Fuhrmann J L, Nguyen D, Utterback T R, Kelley J M, Peterson J D, Sadow P W, Hanna M C, Cotton M D, Roberts K M, Hurst M A, Kaine B P, Borodovsky M, Klenk H-P, Fraser C M, Smith H O, Woese C R, Venter J C. Complete genome sequence of the methanogenic archaeon, Methanococcus jannaschii. Science. 1996;273:1058–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5278.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang G W, Chang J T. Evidence for the B12-dependent enzyme ethanolamine deaminase in Salmonella. Nature. 1975;254:150–151. doi: 10.1038/254150a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crossman L C, Moir J W B, Enticknap J J, Richardson D J, Spiro S. Heterologous expression of heterotrophic nitrification genes. Microbiology. 1997;143:3775–3783. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-12-3775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crouzet J, Cameron B, Cauchois L, Rigault S, Rouyez M-C, Blanche F, Thibaut D, Debussche L. Genetic and sequence analysis of an 8.7-kilobase Pseudomonas denitrificans fragment carrying eight genes involved in transformation of precorrin-2 to cobyrinic acid. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:5980–5990. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.10.5980-5990.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Mot R, Nagy I, Schoofs G, van der Leyden J. Sequences of the cobalamin biosynthetic genes cobK, cobL and cobM from Rhodococcus sp. NI86/21. Gene. 1994;143:91–93. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90610-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Vries G E, Harms N, Hoogendijk J, Stouthamer A H. Isolation and characterization of Paracoccus denitrificans mutants with increased conjugation frequencies and pleiotropic loss of a (nGATCn) DNA-modifying property. Arch Microbiol. 1989;152:52–57. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gleason F K, Hogenkamp H P C. 5′-Deoxyadenosylcobalamin-dependent ribonucleotide reductase: a survey of its distribution. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1972;277:466–470. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(72)90089-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harms N, de Vries G E, Maurer K, Veltkamp E, Stouthamer A H. Isolation and characterization of Paracoccus denitrificans mutants with defects in the metabolism of one-carbon compounds. J Bacteriol. 1985;164:1064–1070. doi: 10.1128/jb.164.3.1064-1070.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iordan E P, Petukhova N I. Presence of oxygen-consuming ribonucleotide reductase in corrinoid-deficient Propionibacterium freudenreichii. Arch Microbiol. 1995;164:377–381. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jordan A, Reichard P. Ribonucleotide reductases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:71–98. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jordan A, Torrents E, Sala I, Hellman U, Gibert I, Reichard P. Ribonucleotide reduction in Pseudomonas species: simultaneous presence of active enzymes from different classes. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3974–3980. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.13.3974-3980.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kagan R M, Clarke S. Widespread occurrence of three sequence motifs in diverse S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferases suggests a common structure for these enzymes. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994;310:417–427. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaneko T, Sato S, Kotani H, Tanaka A, Asamizu E, Nakamura Y, Miyajima N, Hirosawa M, Sugiura M, Sasamoto S, Kimura T, Hosouchi T, Matsuno A, Muraki A, Nakazaki N, Naruo K, Okumura S, Shimpo S, Takeuchi C, Wada T, Watanabe A, Yamada M, Yasuda M, Tabata S. Sequence analysis of the genome of the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. II. Sequence determination of the entire genome and assignment of potential protein-coding regions. DNA Res. 1996;3:109–136. doi: 10.1093/dnares/3.3.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keen N T, Tamaki S, Kobayashi D, Trollinger D. Improved broad-host-range plasmids for DNA cloning in Gram-negative bacteria. Gene. 1988;70:191–197. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klenk H P, Clayton R A, Tomb J F, White O, Nelson K E, Ketchum K A, Dodson R J, Gwinn M, Hickey E K, Peterson J D, Richardson D L, Kerlavage A R, Graham D E, Kyrpides N C, Fleischmann R D, Quackenbush J, Lee N H, Sutton G G, Gill S, Kirkness E F, Dougherty B A, McKenney K, Adams M D, Loftus B, Peterson S, Reich C I, McNeil L K, Badger J H, Glodek A, Zhou L X, Overbeek R, Gocayne J D, Weidman J F, McDonald L, Utterback T, Cotton M D, Spriggs T, Artiach P, Kaine B P, Sykes S M, Sadow P W, Dandrea K P, Bowman C, Fujii C, Garland S A, Mason T M, Olsen G J, Fraser C M, Smith H O, Woese C R, Venter J C. The complete genome sequence of the archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus. Nature. 1997;390:364–379. doi: 10.1038/37052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller J H. A short course in bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pollich M, Klug G. Identification and sequence analysis of genes involved in late steps of cobalamin (vitamin B12) synthesis in Rhodobacter capsulatus. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4481–4487. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.15.4481-4487.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prentki P, Krisch H M. In vitro insertional mutagenesis with a selectable DNA fragment. Gene. 1984;29:303–313. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prieto R, Fernandez E. Toxicity and mutagenesis by chlorate are independent of nitrate reductase activity in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;237:429–438. doi: 10.1007/BF00279448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raux E, Lanois A, Warren M J, Rambach A, Thermes C. Cobalamin (vitamin B-12) biosynthesis: identification and characterization of a Bacillus megaterium cobI operon. Biochem J. 1998;335:159–166. doi: 10.1042/bj3350159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roth J R, Lawrence J G, Rubenfield M, Kieffer-Higgins S, Church G M. Characterization of the cobalamin (vitamin B12) biosynthetic genes of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3303–3316. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3303-3316.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santander P J, Roessner C A, Stolowich N J, Holderman M T, Scott A I. How corrinoids are synthesized without oxygen: nature’s first pathway to vitamin B12. Chem Biol. 1997;4:659–666. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(97)90221-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scott A I. On the duality of mechanisms of ring contraction in vitamin B12 biosynthesis. Heterocycles. 1994;39:471–476. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scott A I, Roessner C A, Stolowich N J, Spencer J B, Min C, Ozaki S I. Biosynthesis of vitamin B12. Discovery of the enzymes for oxidative ring contraction and insertion of the fourth methyl group. FEBS Lett. 1993;331:105–108. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80306-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simon R, Priefer U, Pühler A. A broad host range mobilisation system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram negative bacteria. Bio/Technology. 1983;1:784–791. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith D R, Doucette-Stamm L A, Deloughery C, Lee H, Dubois J, Aldredge T, Bashirzadeh R, Blakely D, Cook R, Gilbert K, Harrison D, Hoang L, Keagle P, Lumm W, Pothier B, Qiu D, Spadafora R, Vicaire R, Wang Y, Wierzbowski J, Gibson R, Jiwani N, Caruso A, Bush D, Safer H, Patwell D, Prabhakar S, McDougall S, Shimer G, Goyal A, Pietrokvski S, Church G M, Daniels C J, Mao J-I, Rice P, Nölling J, Reeve J N. Complete genome sequence of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum ΔH: functional analysis and comparative genomics. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7135–7155. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.22.7135-7155.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spaink H P, Okker R J H, Wijffelman C A, Pees E, Lugtenberg B J J. Promoters in the nodulation region of the Rhizobium leguminosarum Sym plasmid pRL1JI. Plant Mol Biol. 1987;9:27–39. doi: 10.1007/BF00017984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Spanning R J M, de Boer A P N, Reijnders W N M, De Gier W L, Delorme C O, Stouthamer A H, Westerhoff H V, Harms N, van der Oost J. Regulation of oxidative phosphorylation: the flexible respiratory network of Paracoccus denitrificans. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1995;27:499–512. doi: 10.1007/BF02110190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Spanning R J M, de Boer A P N, Reijnders W N M, Westerhoff H V, van der Oost J. FnrP and Nnr of Paracoccus denitrificans are both members of the FNR family of transcriptional activators but have distinct roles in respiratory adaptation in response to oxygen limitation. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:893–907. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2801638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vlcek C, Paces V, Maltsev N, Paces J, Haselkorn R, Fonstein M. Sequence of a 189-kb segment of the chromosome of Rhodobacter capsulatus SB1003. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9384–9388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zumft W G, Blumle S, Braun C, Korner H. Chlorate resistant mutants of Pseudomonas stutzeri affected in respiratory and assimilatory nitrate utilization and expression of cytochrome cd1. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;91:153–158. [Google Scholar]