Abstract

In gram-positive bacteria, the HPr protein of the phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system (PTS) can be phosphorylated on a histidine residue at position 15 (His15) by enzyme I (EI) of the PTS and on a serine residue at position 46 (Ser46) by an ATP-dependent protein kinase (His∼P and Ser-P, respectively). We have isolated from Streptococcus salivarius ATCC 25975, by independent selection from separate cultures, two spontaneous mutants (Ga3.78 and Ga3.14) that possess a missense mutation in ptsH (the gene encoding HPr) replacing the methionine at position 48 by a valine. The mutation did not prevent the phosphorylation of HPr at His15 by EI nor the phosphorylation at Ser46 by the ATP-dependent HPr kinase. The levels of HPr(Ser-P) in glucose-grown cells of the parental and mutant Ga3.78 were virtually the same. However, mutant cells growing on glucose produced two- to threefold less HPr(Ser-P)(His∼P) than the wild-type strain, while the levels of free HPr and HPr(His∼P) were increased 18- and 3-fold, respectively. The mutants grew as well as the wild-type strain on PTS sugars (glucose, fructose, and mannose) and on the non-PTS sugars lactose and melibiose. However, the growth rate of both mutants on galactose, also a non-PTS sugar, decreased rapidly with time. The M48V substitution had only a minor effect on the repression of α-galactosidase, β-galactosidase, and galactokinase by glucose, but this mutation abolished diauxie by rendering cells unable to prevent the catabolism of a non-PTS sugar (lactose, galactose, and melibiose) when glucose was available. The results suggested that the capacity of the wild-type cells to preferentially metabolize glucose over non-PTS sugars resulted mainly from inhibition of the catabolism of these secondary energy sources via a HPr-dependent mechanism. This mechanism was activated following glucose but not lactose metabolism, and it did not involve HPr(Ser-P) as the only regulatory molecule.

The phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system (PTS) is the principal sugar transport system in oral streptococci (41). The PTS uses phosphoenolpyruvate in a group translocation process to phosphorylate incoming sugars via a cascade of phosphoryl transfers involving the non-sugar-specific proteins enzyme I (EI) and HPr and a family of sugar-specific, membrane-bound enzyme II (EII) complexes that catalyze the transport and phosphorylation of mono- and disaccharides (28). The EII complexes commonly comprise three distinct regions or domains, designated A, B, and C, that can be found on a single protein or on separate polypeptides (32). EI, HPr, and domains IIA and IIB sequentially transfer the phosphate group from phosphoenolpyruvate to the incoming sugar. Domain IIC is not phosphorylated and forms the transmembrane channel whereby sugars diffuse into the cell. During sugar transport, the protein HPr is phosphorylated by phospho-EI on a histidine (His) residue at position 15 (His∼P). HPr(His∼P) subsequently transfers its phosphate group to a IIA domain, which itself phosphorylates its IIB counterpart. The phosphoryl group is then transferred to the incoming sugar (for reviews, see references 23, 28, and 32).

In gram-positive bacteria, HPr can also be phosphorylated on a serine (Ser) residue at position 46 by an ATP-dependent HPr(Ser) kinase (Ser-P) (4, 8, 11, 29). HPr(Ser-P) cannot transfer its phosphate group to PTS IIA domains and thus does not participate in sugar transport (8). Compelling evidence has indicated that HPr(Ser-P) is involved in catabolite repression either by expelling inducers or preventing their entry (42–44) or by regulating gene transcription (7). The latter function is accomplished in conjunction with a DNA binding protein called CcpA that recognizes a specific DNA sequence called CRE located in the promoter region of target operons. The association of CcpA with a number of CRE sequences is promoted by HPr(Ser-P) (6, 10, 15, 20) and results in the activation or inhibition of gene transcription depending on whether the CRE sequence is located upstream or downstream from the promoter sequence (17, 19). Several results indicated that HPr(His∼P) is also involved in the regulation of sugar metabolism in gram-positive bacteria by controlling the activity of the lactose permease of Streptococcus thermophilus (27), the catabolic enzyme glycerol kinase of Enterococcus faecalis (9), and transcriptional regulatory proteins (34) by reversible phosphorylation of histidine residues.

The mechanisms by which HPr of oral streptococci exerts its regulatory functions are still poorly understood. Several findings, however, suggest that they may differ to some extent from those reported in other gram-positive bacteria with low guanine-plus-cytosine contents. For example, unlike other gram-positive bacteria, the HPr(Ser) kinase of oral streptococci, as that of E. faecalis (21), is not activated by fructose-1,6-diphosphate (4, 35), nor does its product, HPr(Ser-P), function to reduce PTS activity (35). Moreover, inactivation of regM, a gene coding for a CcpA homologue, does not abolish catabolite repression in Streptococcus mutans (33). Finally, exponentially growing cells of oral streptococci possess significant amounts of the doubly phosphorylated product HPr(Ser-P)(His∼P) (35, 38). The presence of this intermediate has not been reported in other bacteria in vivo, although the formation of the doubly phosphorylated product under in vitro conditions was shown with HPrs from Streptococcus pyogenes (30) and E. faecalis (5). Nevertheless, recent results obtained with a Streptococcus salivarius HPr mutant in which Ile-47 was replaced by a threonine unequivocally demonstrate the involvement of streptococcal HPr in the regulation of catabolic gene expression (14). In this work, we report the analysis of ptsH mutants from S. salivarius with a point mutation replacing HPr Met-48 with a valine.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

S. salivarius ATCC 25975 was provided by I. R. Hamilton (University of Manitoba). Strains Ga3.14 and Ga3.78 are spontaneous mutants independently isolated from S. salivarius by positive selection on a medium containing 200 mM galactose and 5 mM 2-deoxyglucose. These mutants have a missense mutation in the ptsH gene resulting in the substitution of the methionine (Met) at position 48 in HPr by a valine (Val) (M48V). Cells were grown at 37°C in a medium containing 10 g of tryptone, 5 g of yeast extract (Difco Laboratories), 2.5 g of NaCl, and 2.5 g of disodium phosphate per liter. Sugars were sterilized by filtration (0.22-μm-pore-size filter; Millipore) and were added aseptically to the medium to give the appropriate concentrations. Cells of the parental strain cultured in this medium with no sugar added grew to an optical density at 660 nm (OD660) of approximately 0.1 and then growth stopped. Generation times were determined by culturing the cells at 37°C in the presence of 0.5% sugar in tubes (16 by 125 mm) containing 8 ml of medium. Cultures were inoculated with 0.4 ml of an overnight culture grown in the presence of 0.1% sugar. Growth was monitored by following the OD660. Generation times were calculated for cultures in exponential growth by plotting the logarithm of the OD660 as a function of time. For growth studies in media containing two sugars, cells were grown in tubes containing 15 ml of medium and the following mixtures of sugars: (i) 0.1% (wt/vol) glucose (a PTS sugar) and 0.2% (wt/vol) galactose, lactose, or melibiose (non-PTS sugars) or (ii) 0.2% (wt/vol) lactose and 0.1% (wt/vol) galactose. Samples (0.5 ml) were taken at intervals, were heated at 100°C for 10 min to stop metabolism, were centrifuged to remove cells, and were kept at −20°C for sugar determinations.

Metabolism of sugars by resting cells.

Cells were cultured in the presence of 0.2% (wt/vol) sugar, and growth was stopped during the exponential phase of growth (OD660 of approximately 0.4) by the addition of chloramphenicol (50 μg/ml). The cells were harvested by a 5-min centrifugation at 22,000 × g, were washed twice with 10 mM MgSO4, and were resuspended in 100 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0) at 200 mg/ml (wet weight). One milliliter of this cell suspension was added to 9 ml of 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). The cellular suspension was maintained at 37°C and was gently mixed on a magnetic stirrer. After 5 min of preincubation, sugars were added to a final concentration of 0.2 or 0.4% (wt/vol), and the pH was maintained at 7.0 ± 0.1 by automatic titration using 0.1 N NaOH. Samples (0.25 to 0.5 ml) were taken at intervals, were heated at 100°C for 10 min, were centrifuged to remove cells, and were kept at −20°C for sugar determinations.

HPr determination.

The different forms of HPr in growing cells were determined by crossed immunoelectrophoresis (38). Cells were grown in the presence of 0.5% (wt/vol) sugar. When the culture reached mid-log phase, chloramphenicol (50 μg/ml) and Gramicidin D (1 μM) were added, the pH was adjusted to 4.5 using HCl, and the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4°C. This procedure was shown to inactivate EI, the HPr(Ser) kinase, and the HPr(Ser-P) phosphatase (38). The cells were ruptured by grinding with alumina (36) in 10 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.0) containing 0.1 μM Pepstatine A, 0.1 μM leupeptine, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 14 mM 2-mercaptoethanol. The mixture was centrifuged first at 3,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C to remove intact cells and alumina and then at 16,000 × g for 20 min to remove cell debris. Cytoplasmic proteins were separated from the membrane fragments by ultracentrifugation (150,000 × g for 16 h). Crossed immunoelectrophoresis was carried out as described (38). A standard curve was obtained by using purified HPr from S. salivarius.

ATP-dependent phosphorylation of HPr.

The [32P]ATP-dependent phosphorylation of HPr was performed as described by Thevenot et al. (35) using membrane fragments of wild-type S. salivarius as a source of HPr(Ser) kinase or using purified recombinant HPr(Ser) kinase from S. salivarius (4). The product, HPr(Ser-32P), was separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) in the presence of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) (22) and was located by autoradiography by placing the dried gel on Kodak X-ray film (X-Omat AR) for 16 h at room temperature.

Ion-spray mass spectroscopy.

Molecular mass determination of HPr by mass spectroscopy was carried out with a triple quadropole mass spectrometer API III LC/MS/MS system as described previously (40). Presumptive HPr(Ser-P) was purified from mutant Ga3.78 as described previously (31). The homogeneity of the preparation was confirmed by SDS-PAGE. As S. salivarius possesses two forms of HPr that can be distinguished by the absence (HPr-1) or presence (HPr-2) of the N-terminal Met (40), the preparation of phospho-HPr was further purified by preparative electrophoresis as described previously (31) to separate phospho-HPr-1 from phospho-HPr-2. Phospho-HPr-1 was used for mass spectroscopy analyses.

Treatment with alkaline phosphatase.

Phospho-HPr purified from mutant Ga3.78 was incubated in the presence of calf intestine alkaline phosphatase (Stratagene) at 37°C for 17 h in a buffer containing 100 mM sodium carbonate (pH 10.3), 2 to 8 units of phosphatase, and 1.5 μg of phospho-HPr. Samples were then analyzed by native PAGE as described previously (31).

IIABMan analysis by Western blotting.

The IIABMan content of mutant strains was determined by SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis as described previously (13). Visualization was carried out with rabbit polyclonal antibodies directed against S. salivarius IIABHMan and anti-rabbit alkaline phosphatase conjugate by following the manufacturer’s instructions (Bio-Rad). Anti-IIABHMan antibodies react with both IIABHMan and IIABLMan (2).

Enzymatic assays.

Cellular extracts used for the determination of enzyme activities were prepared as described by Gauthier et al. (14). β-Galactosidase activity was determined using o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG) as the substrate (16), whereas α-galactosidase activity was determined using p-nitrophenyl-α-galactopyranoside (25). Galactokinase was determined by measuring the rate of phosphorylation of [14C]galactose at the expense of ATP as described previously (37). Assays were performed under conditions where the rate of reaction was constant with the time of incubation and proportional to the enzyme concentration.

Protein and sugar determinations.

Protein concentrations were determined by the method of Peterson (26) or Bradford (3) with bovine serum albumin as the standard. Glucose was determined using a peroxidase-glucose oxidase assay (Sigma). Lactose and melibiose were assayed in the presence of glucose by measuring the concentration of glucose in samples before and after acid hydrolysis (7.2 N H2SO4 for 2 h at 100°C). Lactose was also assayed by measuring the amount of glucose or galactose produced after hydrolysis of the disaccharide with β-galactosidase in 350 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.6) containing 89 mM MgSO4 and 144 U of β-galactosidase (Worthington) per μl. Galactose was determined with a peroxidase-galactose oxidase assay (1).

RESULTS

Generation times.

Generation times of the wild-type and mutant strains in the presence of PTS sugars (glucose, fructose, and mannose) and non-PTS sugars (lactose and melibiose) are listed in Table 1. The growth of mutant strains on PTS sugars was not affected, indicating that the mutation did not impede the transfer of the phosphate group from phospho-EI to HPr and from HPr(His∼P) to IIA domains. Growth on lactose and melibiose was also unchanged. However, the growth of both mutants on galactose was modified, as the growth curve plotted as the logarithm of absorbance versus time was not linear and rapidly decreased with time (data not shown). This aberrant growth prevented the determination of the generation time on galactose. Therefore, two mutants bearing the identical alteration in the HPr protein were found to behave the same when grown in a range of sugars.

TABLE 1.

Generation times of S. salivarius ATCC 25975 and mutants Ga3.14 and Ga3.78

| Sugar (0.5%) | Generation time ofa:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parental strain | Mutant Ga3.14 | Mutant Ga3.78 | |

| Glucose | 31 ± 1 | 33 ± 4 | 32 ± 1 |

| Fructose | 30 ± 4 | 35 ± 2 | 31 ± 1 |

| Mannose | 38 ± 2 | 38 ± 1 | 36 ± 1 |

| Lactose | 39 ± 2 | 33 ± 1 | 36 ± 2 |

| Melibiose | 34 ± 1 | 36 ± 1 | 37 ± 2 |

Values represent the means ± standard errors of three separate experiments and are expressed in minutes.

Growth on mixed substrates.

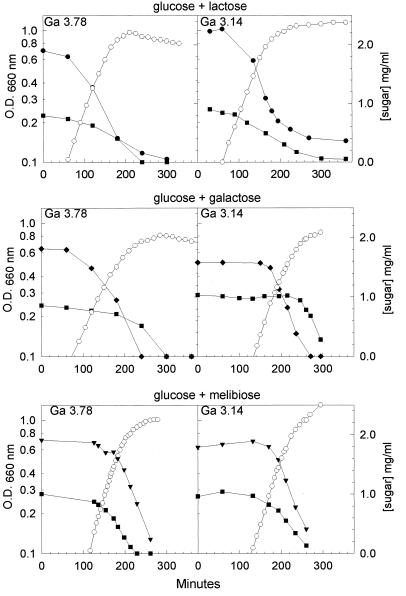

When the wild-type strain was cultured in mixtures containing glucose (a PTS sugar) and a non-PTS sugar (lactose, melibiose, or galactose), the growth curve was diauxic (i.e., glucose was metabolized, and there was a pause in growth before the non-PTS sugar was consumed [data not shown and references 12 and 14]). In contrast, in a mixture containing lactose and galactose, two non-PTS sugars, the growth of the wild-type strain was not diauxic and both sugars were used concurrently (data not shown). Growth of mutants Ga3.78 and Ga3.14 in mixtures containing glucose and a non-PTS sugar was never diauxic (Fig. 1). However, the pattern of sugar utilization was unpredictable. In glucose-lactose and glucose-melibiose mixtures, the mutants metabolized both sugars at the same time. With the glucose-galactose combination, the galactose was consumed before the glucose.

FIG. 1.

Growth of mutants Ga3.78 and Ga3.14 in medium containing glucose and a non-PTS sugar. Cells were grown overnight in the presence of 0.1% glucose. One-milliliter aliquots of glucose-grown cells were used to inoculate 15-ml tubes containing a mixture of glucose and non-PTS sugars (lactose, galactose, and melibiose). The symbols represent the OD660 (○) and the consumption of glucose (■), lactose (●), galactose (⧫), and melibiose (▾).

Expression of enzymes involved in the metabolism of non-PTS sugars.

We measured the activities of β-galactosidase, α-galactosidase, and galactokinase, the first enzymes involved in the metabolism of lactose, melibiose, and galactose, respectively. Results shown in Table 2 indicate that the wild-type strain produced only basal levels of these enzymes after growth on glucose. The replacement of Met48 by Val had only a minor effect on the repression of these enzymes by glucose, resulting in an approximately twofold increase in basal activities. In wild-type and mutant strains, growing the cells in the presence of the inducing sugar resulted in a 6- to 185-fold increase in enzyme activity.

TABLE 2.

α-Galactosidase, β-galactosidase, and galactokinase activities in S. salivarius ATCC 25975 and mutants Ga3.14 and Ga3.78

| Strain | Enzyme | Specific activity after growth ona:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | Melibiose | Lactose | Galactose | ||

| Wild-type | α-Galactosidase | 106 ± 48 | 1,288 ± 68 | N.D. | N.D. |

| β-Galactosidase | 28 ± 1 | N.D.b | 753 ± 54 | N.D. | |

| Galactokinase | 4 ± 0.2 | N.D. | N.D. | 740 ± 76 | |

| Mutant Ga3.14 | α-Galactosidase | 251 ± 58 | 1,435 ± 92 | N.D. | N.D. |

| β-Galactosidase | 48 ± 9 | N.D. | 564 ± 192 | N.D. | |

| Galactokinase | 13 ± 4 | N.D. | N.D. | 786 ± 159 | |

| Mutant Ga3.78 | α-Galactosidase | 175 ± 16 | 932 ± 57 | N.D. | N.D. |

| β-Galactosidase | 44 ± 11 | N.D. | 787 ± 67 | N.D. | |

| Galactokinase | 12 ± 2 | N.D. | N.D. | 769 ± 68 | |

Activities are expressed as nanomoles of product per milligram of protein per minute. Each value is the mean (± standard error) of four determinations performed on two different cultures.

N.D., not determined.

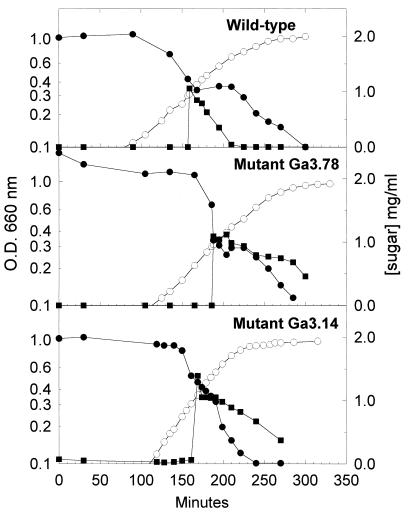

Inducer exclusion by growing cells.

When glucose was added during the exponential phase of growth to wild-type cells growing on medium containing lactose (Fig. 2), galactose, or melibiose (data not shown) as the sole energy source, we observed that the cells rapidly stopped using the non-PTS sugar and consumed glucose exclusively. The metabolism of the non-PTS sugar resumed only when the glucose was depleted. The addition of glucose to mutant cells growing on lactose (Fig. 2), galactose, or melibiose (data not shown) did not prevent the metabolism of these sugars, and both glucose and the non-PTS sugar were used at the same time. Thus, the HPr-M48V mutation prevents induced cells from shutting off the metabolism of a non-PTS sugar when glucose becomes available.

FIG. 2.

Effect of glucose on lactose metabolism by growing cells. Cells were grown overnight in the presence of 0.2% lactose. A 0.75-ml aliquot was used to inoculate 15 ml of culture medium containing 0.2% lactose. When the culture reached mid-log phase, the medium was supplemented with 0.1% glucose. The symbols represent the OD660 (○), the consumption of lactose (●), and the consumption of glucose (■).

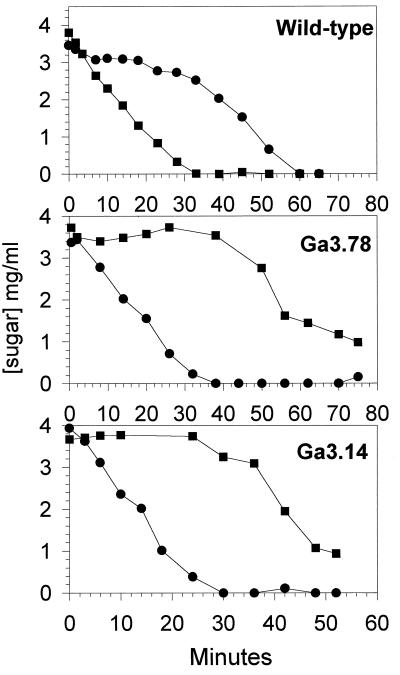

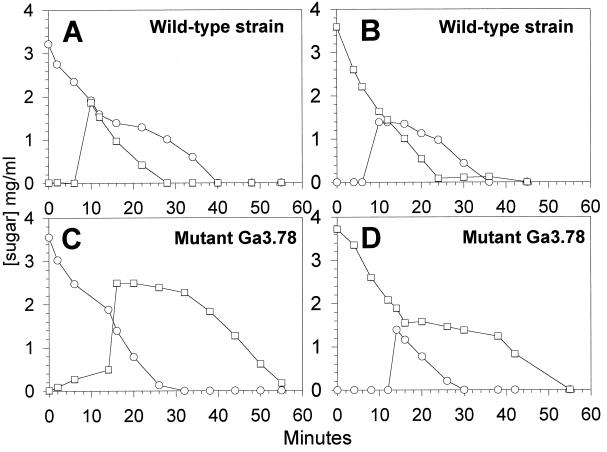

Pattern of sugar utilization by resting cells.

Previous experiments were carried out with growing cells that possessed abundant energy generated from ongoing metabolism. We carried out experiments with resting cells to determine whether the energy status of the cell affected the pattern of sugar metabolism with cells exposed to a mixture of sugars. Lactose-grown cells of wild-type and mutant strains which were harvested at mid-log phase, centrifuged, and suspended in a phosphate buffer for 30 min prior to the addition of an energy source were able to metabolize glucose or lactose at approximately the same rate (data not shown). Consistent with the results obtained with growing cells, resting mutant cells were unable to selectively metabolize glucose over lactose when incubated in a medium containing both sugars, and the cells metabolized lactose before glucose under these conditions (Fig. 3). When wild-type resting cells were incubated in a medium containing lactose and glucose, they simultaneously utilized both sugars for the first 8 min. After this period, lactose consumption stopped, and it resumed only after the glucose was depleted (Fig. 3). Hence, exposure of resting wild-type cells to a mixture of glucose and lactose did not result in immediate and total inhibition of the non-PTS sugar metabolism. These results suggested that resting cells were, at the beginning of the experiment, in a physiological state that did not permit the inhibition of lactose metabolism by external glucose. However, this property was recovered following a period of energy generation. We therefore analyzed the pattern of sugar utilization by resting cells after letting them metabolize an energy source for 10 to 16 min before exposure to a mixture of sugars. Results presented in Fig. 4A were obtained with wild-type resting cells that were first incubated with 0.4% lactose for 10 min. After this, glucose was added to the medium (final concentration, 2%) which still contained approximately 0.2% lactose. The addition of glucose did not instantly prevent the metabolism of lactose, which continued to be metabolized at the same rate for about 2 min. Therefore, the utilization of lactose was strongly reduced and resumed only when the glucose was depleted. When wild-type cells were first incubated in the presence of glucose (Fig. 4B) and then provided with lactose, the disaccharide was ignored by the cells and was slowly metabolized only after the glucose was almost exhausted. Thus, preincubation of wild-type cells with glucose generated a physiological state where external glucose inhibited the metabolism of lactose, a phenomenon not observed when the cells were preincubated with lactose (a non-PTS sugar). This result was consistent with the observation that during growth of the wild-type strain in a mixture of lactose and galactose, lactose was unable to prevent the metabolism of galactose and both sugars were used concomitantly. Experiments conducted in which resting cells of both mutants were preincubated with glucose or lactose did not restore the ability of the cells to consume glucose in preference to the non-PTS sugar; indeed, lactose metabolism was unaffected by the presence of glucose in all cases (results are shown for mutant Ga3.78 only) (Fig. 4C and D). Moreover, lactose prevented the metabolism of glucose.

FIG. 3.

Sugar metabolism by resting cells. Cells were grown in the presence of 0.2% lactose, were harvested during the exponential phase of growth, were washed once, and were suspended in phosphate buffer at pH 7.0. Glucose and lactose (final concentrations, approximately 0.4%) were added at 0 min. The symbols represent the consumption of lactose (●) and the consumption of glucose (■).

FIG. 4.

Sugar metabolism by energized resting cells. Cells were grown in the presence of 0.2% lactose, were harvested during the exponential phase of growth, were washed once, and were suspended in phosphate buffer at pH 7.0. At 0 min, approximately 0.4% lactose (panels A and C) or 0.4% glucose (panels B and D) was added. When the concentration of sugar in the medium was decreased approximately by half, glucose (panels A and C) or lactose (panels B and D) were added at a final concentration of 0.2%. The symbols represent the consumption of lactose (○) and the consumption of glucose (□).

Intracellular concentrations of the different forms of HPr.

As reported previously (38), wild-type cells cultured on glucose contained mainly HPr(Ser-P) and HPr(Ser-P)(His∼P) and very low levels of free HPr and HPr(His∼P) (Table 3). To determine whether these concentrations were modified when cells were cultured on a non-PTS sugar whose metabolism was inhibited by glucose, we determined the levels of the different forms of HPr in cells growing on lactose. The results shown in Table 3 indicate that the levels of each form of HPr in glucose- and lactose-grown cells were virtually the same. To determine whether the M48V mutation prevented the phosphorylation of HPr at Ser46, we analyzed the HPr content of mutant Ga3.78 grown on glucose (Table 3). Surprisingly, we found that the mutant contained high levels of a compound that migrated like HPr(Ser-P). Nevertheless, although the total amount of HPr remained virtually unchanged, the proportions of the four forms of HPr differed from that of the wild-type strain. The levels of free HPr and HPr(His∼P) were much higher and those of the HPr(Ser-P)-like form were the same, while the levels of HPr(Ser-P)(His∼P) were approximately threefold lower.

TABLE 3.

Intracellular levels of the different forms of HPr in S. salivarius ATCC 25975 and mutant Ga3.78a

| Strain | Sugar | Level of:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPr | HPr(His∼P) | HPr(Ser-P) | HPr(Ser-P)(His∼P) | Total HPr | ||

| Parental | Glucose | <1 | 10 ± 6 | 45 ± 9 | 49 ± 20 | 104 |

| Lactose | <1 | 10 ± 3 | 36 ± 17 | 73 ± 7 | 119 | |

| Ga3.78 | Glucose | 18 ± 13 | 27 ± 14 | 45 ± 12 | 14 ± 5 | 104 |

Cells were grown in TYE (tryptone yeast extract) broth supplemented with 0.5% (wt/vol) glucose or lactose and were harvested at mid-log phase. Concentrations are expressed in nanograms of HPr per microgram of cytoplasmic protein. The values (± standard errors) are the means of eight determinations from four cultures for glucose-grown cells of the parental strain and the means of four determinations from two cultures for lactose-grown and glucose-grown cells of the parental strain and mutant Ga3.78, respectively.

Analysis of Ga3.78 putative HPr(Ser-P).

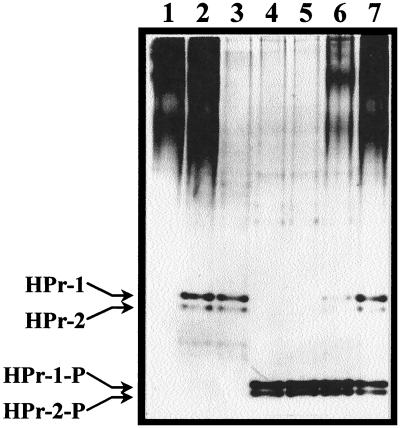

We purified the modified form of HPr from mutant Ga3.78, which migrated in crossed immunoelectrophoresis as HPr(Ser-P). As streptococci possess two forms of HPr that differ by the absence (HPr-1) or presence (HPr-2) of the N-terminal Met (40), we purified the modified form of HPr-1 as described in Materials and Methods and determined the molecular weight of the protein by ion-spray mass spectroscopy. The molecular weight of free HPr-1 determined using this technique is 8,776.48 (40). Taking into account the replacement of Met48 by Val in the HPr of mutant Ga3.78, the calculated molecular weight of mutated free HPr-1 is 8744.38. The molecular weight determined for the modified form of HPr-M48V that migrated as HPr(Ser-P) in crossed immunoelectrophoresis was 8824.86 (± 0.15). The difference between these two molecular weights is 80.47, which is very close to the calculated molecular weight of a phosphate group minus the molecular weight of a water molecule (79.98). These results suggested that the modified form of HPr isolated from mutant Ga3.78 was a phosphate derivative. This was substantiated by the fact that incubation of the purified modified protein in the presence of alkaline phosphatase generated free HPr (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Effect of alkaline phosphatase on the modified form of Ga3.78 HPr. The modified form of HPr was purified to homogeneity from strain Ga3.78 and was incubated in the presence or absence of alkaline phosphatase for 17 h at 37°C. The proteins were separated by PAGE under native conditions that allow the separation of free HPr from phospho-HPr and the separation of HPr-1 (without N-terminal Met) from HPr-2 (with N-terminal Met). The proteins were revealed by staining with silver nitrate. Lane 1, 8 U of alkaline phosphatase; lane 2, 1.5 μg of free Ga3.78 HPr and 8 U of alkaline phosphatase; lane 3, 1.5 μg of free Ga3.78 HPr; lane 4, 1.5 μg of purified modified HPr from mutant Ga3.78; lane 5, 2 μg of purified modified HPr from mutant Ga3.78; lane 6, 1.5 μg of purified modified HPr from mutant Ga3.78 incubated with 2 U of alkaline phosphatase; lane 7, 1.5 μg of purified modified HPr from mutant Ga3.78 incubated with 8 U of alkaline phosphatase.

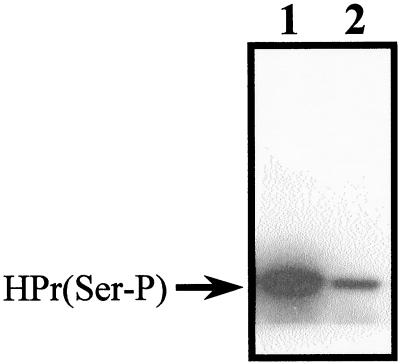

In vitro phosphorylation of HPr by the HPr(Ser) kinase.

The results reported above suggested that HPr-M48V could be phosphorylated on Ser46 in vivo. We thus verified whether the protein could be phosphorylated in vitro at the expense of ATP by the HPr(Ser) kinase. We first carried out the phosphorylation experiment with membrane fragments of the wild-type strain as a source of HPr(Ser) kinase and membrane-free cellular extracts as a source of HPr. Under these conditions, no phosphoryl-derivative of Ga3.78 HPr-M48V could be observed, whereas wild-type phospho-HPr could be easily detected (not shown). We recently cloned S. salivarius hprK, the gene encoding the HPr(Ser) kinase (4). Expression of the enzyme in E. coli enabled us to obtain large amounts of purified enzyme. We then measured the in vitro ATP-dependent phosphorylation of Ga3.78 HPr using recombinant purified S. salivarius HPr(Ser) kinase. The results shown in Fig. 6 indicated that the HPr-M48V was phosphorylated in the presence of 100 ng of purified HPr(Ser) kinase.

FIG. 6.

In vitro phosphorylation of HPr by the ATP-dependent HPr(Ser) kinase. Mutant Ga3.78 was cultured in the presence of 0.5% glucose and was harvested at mid-log phase. A membrane-free cellular extract was obtained after the cells were ruptured by grinding with alumina and differential centrifugation. Purified HPr (2 μg) from the wild-type strain (lane 1) and cellular extract (8.25 μg of proteins) from mutant Ga3.78 (lane 2) were incubated in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP and purified recombinant S. salivarius HPr(Ser) kinase (100 ng). Proteins were then separated by SDS-PAGE, and phosphoproteins were revealed by autoradiography.

Presence of protein IIABLMan in HPr-M48V mutants.

In 1994, we reported the isolation of S. salivarius mutant A66 in which Met48 was replaced by Val (39). Surprisingly, we found that this mutant also lacked protein IIABLMan, a PTS protein involved in the transport of glucose, mannose, and fructose (41). We analyzed the IIABMan content of mutants Ga3.14 and Ga3.78 by Western blotting (Fig. 7) and found that both mutants possessed the two forms of IIABMan (IIABLMan and IIABHMan). These results indicate that the absence of IIABLMan in mutant A66 was not a pleiotropic consequence of the HPr M48V mutation.

FIG. 7.

Western blot analyses with anti-IIABHMan. Cellular extracts containing 25 μg of protein were electrophoresed in 10% acrylamide gels by the method of Laemmli (22) and were electrophoretically transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Lane 1, wild-type strain; lane 2, mutant Ga3.14; lane 3, mutant Ga3.78.

DISCUSSION

In this work, we report the phenotypic consequences resulting from the replacement of Met48 by Val in the HPr protein of S. salivarius. The results were obtained with two spontaneous mutants that were isolated from separate cultures by independent selection and yet possess identical properties and a point mutation resulting in the M48V substitution in the HPr of S. salivarius. A single spontaneous mutation is a rare event, therefore the likelihood of two unidentified mutations spontaneously occurring in two strains and generating the same phenotype is extremely remote. Therefore, both mutants likely carry the single, described mutation that accounts for the observed differences in phenotype from the wild-type parent.

HPrs from gram-positive bacteria can be phosphorylated at a serine residue at position 46 by an ATP-dependent HPr(Ser) kinase. In contrast, HPrs from gram-negative bacteria cannot be phosphorylated by the HPr(Ser) kinase even though they possess Ser46. One striking difference in HPr sequences between gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria is the nature of the residue at position 48. There is a Met at this position in all HPrs from gram-positive bacteria and a phenylalanine in HPrs from gram-negative bacteria. The residue at position 48 is thus considered an important structural element that determines the ability of HPr to interact with the HPr(Ser) kinase (18, 45). In this study, we report several lines of evidence suggesting that the M48V substitution did not prevent phosphorylation of S. salivarius HPr at Ser46 by the HPr(Ser) kinase. The evidence is as follows: (i) analysis of the different forms of HPr in growing cells of mutant Ga3.78 by crossed immunoelectrophoresis revealed the presence of a modified form of HPr that was resistant to heat and migrated as HPr(Ser-P), (ii) analysis of this purified intermediate by mass spectrometry indicated that it possesses the molecular weight predicted for a phosphorylated derivative of HPr, (iii) incubation of this modified form of HPr with alkaline phosphatase generated free HPr; and (iv) incubation of free HPr-M48V with purified recombinant S. salivarius HPr(Ser) kinase and [γ-32P]ATP resulted in the formation of heat-stable phospho-HPr. The mutation had no effect on the total amount of HPr, but it perturbed the relative proportions of the different forms of HPr in growing cells. The levels of free HPr and HPr(His∼P) were higher and those of HPr(Ser-P) remained the same, while the levels of the doubly phosphorylated product were approximately threefold lower. These results suggested that the M48V mutation did not interfere with the phosphorylation of free HPr by the HPr(Ser) kinase in vivo. However, the fact that, in vitro, the mutated HPr could be phosphorylated in the presence of large amounts of purified kinase but not by small amounts of enzyme such as those found in a membrane-free cellular extract suggested that the M48V substitution does interfere with the interaction of the HPr kinase with its substrate. We propose that this effect is counteracted in vivo by the presence of large amounts of HPr, preventing a decrease in the rate of phosphorylation of HPr at Ser46 by the HPr(Ser) kinase. The M48V substitution would also affect the interaction between EI and HPr(Ser-P), as the levels of the doubly phosphorylated product were threefold lower.

Growth of the mutants on PTS sugars remained virtually unchanged. This is consistent with the observation that the levels of HPr(His∼P) were high in mutant Ga3.78. This also suggests that the M48V mutation does not interfere with the interaction of HPr(His∼P) with IIA domains. Growth on the non-PTS sugars lactose and melibiose was also unchanged. However, growth on galactose, also a non-PTS sugar, was modified, as the growth was not exponential. Recently, Luesink et al. (24) found that ptsH and ptsI mutants of Lactococcus lactis have reduced growth on the non-PTS sugars galactose and maltose. These authors suggested that the metabolism of these sugars in L. lactis is stimulated by HPr(His∼P). This hypothesis does not explain the aberrant growth on galactose of M48V S. salivarius mutants, as more HPr(His∼P) was found in mutant Ga3.78 than in the parental strain. At this time we have no explanation for this phenotype.

Unlike with the wild-type strain, growing mutants in media containing glucose and non-PTS sugars never resulted in the preferential metabolism of glucose over the non-PTS sugar. This deficiency may be caused by the derepression of genes coding for permeases and enzymes involved in the metabolism of non-PTS sugars and/or by an incapacity to control proteins involved in the catabolism of these secondary energy sources. These results indicated that the M48V substitution had only a minor effect on the regulatory functions of HPr associated with gene expression. Indeed, determination of α-galactosidase, β-galactosidase, and galactokinase activities revealed that the encoding genes were expressed at basal levels in the wild-type strain after growth on glucose and that the genes were only slightly derepressed (about twofold) in the mutants cultured under the same conditions, while levels in induced cells increased 6- to 185-fold.

The addition of glucose to wild-type cells growing in the presence of lactose, galactose, or melibiose rapidly resulted in the inhibition of lactose, galactose, or melibiose consumption, which resumed only when the glucose in the medium was depleted. In contrast, the presence of glucose did not stop the metabolism of the non-PTS sugars by growing mutants Ga3.78 and Ga3.14. These results suggest that HPr regulates proteins involved in the catabolism of non-PTS sugars in oral streptococci and that replacement of HPr Met48 by Val prevents this.

Experiments with resting cells have demonstrated, however, that the presence of glucose in the medium did not constitute per se a sufficient condition to prevent the catabolism of non-PTS sugars by wild-type cells. The results indicated that the ability of the cells to exclude secondary energy sources in the presence of glucose is acquired following glucose metabolism, a property that is not acquired following the metabolism of lactose. Surprisingly, however, lactose- and glucose-grown cells contained virtually the same levels of the different forms of HPr, including HPr(Ser-P). Thus, although the physiological state permitting the exclusion of non-PTS sugars is linked to HPr, as is demonstrated by the behavior of mutants Ga3.78 and Ga3.14, it is obviously not the only molecule involved.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the Medical Research Council of Canada (grant MT-6979) to C.V., the Conseil des Recherches en Pêche et en Agroalimentaire du Québec (CORPAQ, grant 4486) to C.V. and M.F., and the Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec to M.F. P.P. was this recipient of a studentship from the CRSNG.

REFERENCES

- 1.Avigad G, Amaval D, Ascensio C, Horecker B L. The d-galactose oxydase of Polyporus circinatus. J Biol Chem. 1962;237:2736–2743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bourassa S, Gauthier L, Giguère R, Vadeboncoeur C. A IIIMan protein is involved in the transport of glucose, mannose, and fructose by oral streptococci. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1990;5:288–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1990.tb00427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brochu D, Vadeboncoeur C. The HPr(serine) kinase of Streptococcus salivarius: purification, properties, and cloning of the hprK gene. J Bacteriol. 1998;181:709–717. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.3.709-717.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deutscher J, Engelmann R. Purification and characterization of an ATP-dependent protein kinase from Streptococcus faecalis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1984;23:157–162. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deutscher J, Küster E, Bergstedt U, Charrier V, Hillen W. Protein kinase-dependent HPr/CcpA interaction links glycolytic activity to carbon catabolite repression in gram-positive bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:1049–1053. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deutscher J, Reizer J, Fisher C, Galinier A, Saier M H, Jr, Steinmetz M. Loss of protein kinase-catalyzed phosphorylation of HPr, a phosphocarrier protein of the phosphotransferase system, by mutation of the ptsH gene confers catabolite repression resistance to several catabolic genes of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3336–3344. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.11.3336-3344.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deutscher J, Saier M H., Jr ATP-dependent protein kinase-catalyzed phosphorylation of a seryl residue in HPr, a phosphate carrier protein of the phosphotransferase system in Streptococcus pyogenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:6790–6794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.22.6790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deutscher J, Sauervald H. Stimulation of dihydroxyacetone and glycerol kinase activity in Streptococcus faecalis by phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent phosphorylation catalyzed by enzyme I and HPr of the phosphotransferase system. J Bacteriol. 1986;166:829–836. doi: 10.1128/jb.166.3.829-836.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujita Y, Miwa Y, Galinier A, Deutscher J. Specific recognition of the Bacillus subtilis gnt cis-acting catabolite-responsive element by a protein complex formed between CcpA and seryl-phosphorylated HPr. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:953–960. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17050953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galinier A, Kravanja M, Engelmann R, Hengstenberg W, Kilhoffer M C, Deutscher J, Haiech J. New protein kinase and protein phosphatase families mediate signal transduction in bacterial catabolite repression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1823–1828. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gauthier L, Bourassa S, Brochu D, Vadeboncoeur C. Control of sugar utilization in oral streptococci. Properties of phenotypically distinct 2-deoxyglucose-resistant mutants of Streptococcus salivarius. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1990;5:352–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1990.tb00440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gauthier L, Thomas S, Gagnon G, Frenette M, Trahan L, Vadeboncoeur C. Positive selection for resistance to 2-deoxyglucose gives rise, in Streptococcus salivarius, to seven classes of pleiotropic mutants, including ptsH and ptsI missense mutants. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:1101–1109. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gauthier M, Brochu D, Eltis L D, Thomas S, Vadeboncoeur C. Replacement of isoleucine-47 by threonine in the HPr protein of Streptococcus salivarius abrogates the preferential metabolism of glucose and fructose over lactose and melibiose but does not prevent the phosphorylation of HPr on serine-46. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:695–705. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4981870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gösseringer R, Küster E, Galinier A, Deutscher J, Hillen W. Cooperative and non-cooperative DNA binding modes of catabolite control protein CcpA from Bacillus megaterium result from sensing two different signals. J Mol Biol. 1997;266:665–676. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamilton I R, Lo G C Y. Co-induction of β-galactosidase and the lactose-P-enolpyruvate phosphotransferase system in Streptococcus salivarius and Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol. 1978;136:900–908. doi: 10.1128/jb.136.3.900-908.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henkin T M. The role of the CcpA transcriptional regulator in carbon metabolism in Bacillus subtilis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;135:9–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb07959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herzberg O, Reddy P, Sutrina S, Saier M H, Jr, Reizer J, Kapadia G. Structure of the histidine-containing phosphocarrier protein HPr from Bacillus subtilis at 2.0-Å resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:2499–2503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hueck C J, Hillen W, Saier M H., Jr Analysis of a cis-acting sequence mediating catabolite repression in gram-positive bacteria. Res Microbiol. 1994;145:503–518. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(94)90028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones B E, Dossonnet V, Küster E, Hillen W, Deutscher J, Klevit R E. Binding of the catabolite repressor protein CcpA to its target is regulated by phosphorylation of its corepressor HPr. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:26530–26535. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kravanja M, Engelmann R, Dossonnet V, Blüggel M, Meyer H E, Frank R, Galinier A, Deutscher J, Schnell N, Hengstenberg W. The hprK gene of Enterococcus faecalis encodes a novel bifunctional enzyme: the HPr kinase/phosphatase. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:59–66. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lengeler J W, Jahreis K, Wehmeier U F. Enzymes II of the phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent phosphotransferase systems: their structure and function in carbohydrate transport. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1188:1–28. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(94)90017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luesink E J, Christel M A B, Kuipers O P, de Vos W M. Molecular characterization of the Lactococcus lactis ptsHI operon and analysis of the regulatory role of HPr. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:764–771. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.3.764-771.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCleary B V. α-Galactosidase from luciferine and guar seed. Methods Enzymol. 1988;160:627–632. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peterson G L. Determination of total protein. Methods Enzymol. 1983;91:95–119. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(83)91014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poolman B, Knol J, Mollet B, Nieuwenhuis B, Sulter G. Regulation of bacterial sugar-H+ symport by phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent enzyme I/HPr-mediated phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:778–782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.3.778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Postma P W, Lengeler W, Jacobson G R. Phosphoenolpyruvate:carbohydrate phosphotransferase system of bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:543–594. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.3.543-594.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reizer J, Hoischen C, Titgemeyer F, Rivolta C, Rabus R, Stülke J, Karamata D, Saier M H, Jr, Hillen W. A novel protein kinase that controls carbon catabolite repression in bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:1157–1169. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reizer J, Novotny M J, Hengstenberg W, Saier M H., Jr Properties of ATP-dependent protein kinase from Streptococcus pyogenes that phosphorylates a seryl residue in HPr, a phosphocarrier protein of the phosphotransferase system. J Bacteriol. 1984;160:333–340. doi: 10.1128/jb.160.1.333-340.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robitaille D, Gauthier L, Vadeboncoeur C. The presence of two forms of the phosphocarrier protein HPr of the phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system in streptococci. Biochimie (Paris) 1991;73:573–581. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(91)90025-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saier M H, Jr, Reizer J. Proposed uniform nomenclature for the proteins and protein domains of the bacterial phophoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1433–1438. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.5.1433-1438.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simpson C L, Russell R R B. Identification of a homolog of CcpA catabolite repressor protein in Streptococcus mutans. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2085–2092. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2085-2092.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stülke J, Arnaud M, Rapoport G, Martin-Verstraete I. PRD—a protein domain involved in PTS-dependent induction and carbon catabolite repression of catabolic operons in bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:865–874. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thevenot T, Brochu D, Vadeboncoeur C, Hamilton I R. Regulation of ATP-dependent P-(Ser)-HPr formation in Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus salivarius. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2751–2759. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.10.2751-2759.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vadeboncoeur C. Structure and properties of the phosphoenolpyruvate:glucose phosphotransferase system of oral streptococci. Can J Microbiol. 1984;30:495–502. doi: 10.1139/m84-073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vadeboncoeur C, Bourgeau G, Mayrand D, Trahan L. Control of sugar utilization in the oral bacteria Streptococcus salivarius and Streptococcus sanguis by the phosphoenolpyruvate:glucose phosphotransferase system. Arch Oral Biol. 1983;28:123–131. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(83)90119-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vadeboncoeur C, Brochu D, Reizer J. Quantitative determination of the intracellular concentration of the various forms of HPr, a phosphocarrier protein of the phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system in growing cells of oral streptococci. Anal Biochem. 1991;196:24–30. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90112-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vadeboncoeur C, Gauthier L, Gagnon G, Leduc A, Brochu D, Lapointe R, Desjardins B, Frenette M. Properties of a Streptococcus salivarius mutant in which the methionine at position 48 in the protein HPr has been replaced by a valine. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:524–527. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.2.524-527.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vadeboncoeur C, Konishi Y, Dumas F, Gauthier L, Frenette M. HPr polymorphism in oral streptococci is caused by the partial removal of the N-terminal methionine. Biochimie (Paris) 1991;73:1427–1430. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(91)90174-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vadeboncoeur C, Pelletier M. The phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system of oral streptococci and its role in the control of sugar metabolism. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1997;19:187–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1997.tb00297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ye J J, Neal J W, Cui X, Reizer J, Saier M H., Jr Regulation of the glucose:H+ symporter by metabolite-activated ATP-dependent phosphorylation of HPr in Lactobacillus brevis. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3484–3492. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.12.3484-3492.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ye J J, Reizer J, Cui X, Saier M H., Jr Inhibition of the phosphoenolpyruvate:lactose phosphotransferase system and activation of a cytoplasmic sugar-phosphate phosphatase in Lactococcus lactis by ATP-dependent metabolite-activated phosphorylation of serine 46 in the phosphocarrier protein HPr. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:11837–11844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ye J J, Reizer J, Cui X, Saier M H., Jr ATP-dependent phosphorylation of serine-46 in the phosphocarrier protein HPr regulates lactose/H+ symport in Lactobacillus brevis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3102–3106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhu, P. P., O. Herzberg, and A. Peterkofsky. 1998. Topography of the interaction of HPr(Ser) kinase with HPr. 37:11762–11770. [DOI] [PubMed]