Several factors were associated with higher coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-related anxiety.

Higher COVID-19-related anxiety was associated not only with mask wearing but also with weight gain and less adherence to healthier lifestyles.

Interventions are needed to support healthy behaviors in patients with CKD experiencing increased anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, anxiety, chronic kidney disease, chronic renal disease, COVID-19, disparity, epidemiology and outcomes, SARS-CoV-2

Visual Abstract

Abstract

Background

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is associated with anxiety and depression. Although the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has increased stressors on patients with CKD, assessments of anxiety and its predictors and consequences on behaviors, specifically virus mitigation behaviors, are lacking.

Methods

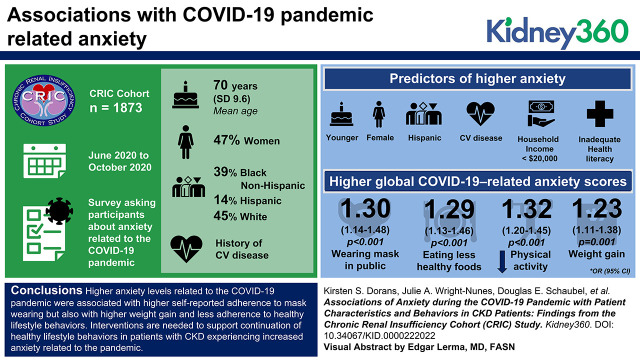

From June to October 2020, we administered a survey to 1873 patients in the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study, asking participants about anxiety related to the COVID-19 pandemic. We examined associations between anxiety and participant demographics, clinical indexes, and health literacy and whether anxiety was associated with health-related behaviors and COVID-19 mitigation behaviors.

Results

The mean age of the study population was 70 years (SD=9.6 years), 47% were women, 39% were Black non-Hispanic, 14% were Hispanic, and 38% had a history of cardiovascular disease. In adjusted analyses, younger age, being a woman, Hispanic ethnicity, cardiovascular disease, household income <$20,000, and marginal or inadequate health literacy predicted higher anxiety. Higher global COVID-19-related anxiety scores were associated with higher odds of reporting always wearing a mask in public (OR=1.3 [95% CI, 1.14 to 1.48], P<0.001) and of eating less healthy foods (OR=1.29 [95% CI, 1.13 to 1.46], P<0.001), reduced physical activity (OR=1.32 [95% CI, 1.2 to 1.45], P<0.001), and weight gain (OR=1.23 [95% CI, 1.11 to 1.38], P=0.001).

Conclusions

Higher anxiety levels related to the COVID-19 pandemic were associated not only with higher self-reported adherence to mask wearing but also with higher weight gain and less adherence to healthy lifestyle behaviors. Interventions are needed to support continuation of healthy lifestyle behaviors in patients with CKD experiencing increased anxiety related to the pandemic.

Introduction

Patients with CKD are at high risk for poor clinical outcomes, including ESKD and cardiovascular complications (1,2). In addition, patients who have CKD experience a high prevalence of depression and anxiety (3). A systematic review estimated 19% prevalence of anxiety disorders and 43% prevalence of high-anxiety symptoms among adults with CKD (4). Anxiety has been linked to poorer ratings of self-reported health in other chronic conditions (5). Further, low health-related quality of life and diminished well-being often co-exist in patients with CKD, potentially leading to even worse clinical outcomes, including premature mortality (6,7).

The devastating and negative consequences of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic are far-reaching and difficult to quantify. The negative effect of the pandemic spans economic, physical, and mental health domains (8). Anxiety, an important target to address in support of mental health, is particularly relevant in CKD. Patients with CKD face challenges managing their chronic condition with the many demands it places on them. CKD patients are at substantially elevated risk of COVID-19-related adverse outcomes and mortality (9,10). Further, during the pandemic, patients have faced new dilemmas related to maintaining employment and healthy relationships while optimizing physical health, all while trying to avoid contracting or spreading COVID-19. Interactions with other people, which in the past may have helped to alleviate anxiety, were drastically altered, reduced, or even eliminated. When they did occur, interactions during the pandemic were often adversely affected by guidelines or laws that reduced physical contact, increased distance from others, and employed physical (e.g., face masks) or other (e.g., vaccine) barriers to interaction.

As a result, patients with CKD could be particularly vulnerable to developing anxiety or worsening of preexisting anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic that could lead to behaviors that limit their risk of contracting or spreading COVID-19 or to unhealthy lifestyle behaviors that could accelerate their disease. Understanding more about anxiety that patients have experienced during this pandemic could be used to inform interventions to reduce or to channel anxiety constructively. Further, identifying predictors or characteristics placing patients at higher risk for anxiety could allow for tailoring of interventions that can prevent or reduce anxiety during or outside of a pandemic.

Here, we report results of a study assessing anxiety related to COVID-19 in patients with CKD. The assessment was performed via a survey administered to participants in the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study from June to October 2020. We examined patient self-report of anxiety, underlying subconstructs of anxiety, and whether and to what extent anxiety was associated with patient-level factors or selected behaviors, including some virus-mitigation behaviors.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Population

Prior publications have described the design of the CRIC Study (11–13). This study recruited 5625 men and women with mild to moderate CKD in the United States. Participants were recruited from seven clinical centers in two phases: (1) phase 1, from 2003 to 2008 (3939 participants) and (2) phase 3, from 2013 to 2015 (1686 participants). Major eligibility criteria for phase 1 included adults aged 21–74 years with an eGFR of 20–70 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Major eligibility criteria for phase 3 included eGFR 45–70 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and age 45–79 years. All CRIC participants provided written informed consent. Institutional Review Boards at each participating site approved the CRIC protocol, and the protocol was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

COVID-19 Survey

CRIC participants completed a telephone survey regarding how COVID-19 was affecting their lives. Survey questions included the components described below. For this analysis, trained research staff called all 2860 enrolled CRIC study participants from June to October 2020 to invite them to participate in a telephone survey regarding their experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic (1805 participants had died before this time; others had withdrawn or not registered for follow-up for unknown reasons). Survey data were collected before emergency use authorization of COVID-19 vaccines in the United States.

Anxiety, Worry, and Mood

Via survey items, participants reported whether they strongly disagreed, disagreed, neither agreed nor disagreed, agreed, or strongly agreed with the statements shown in Supplemental Table 1, all of which related to symptoms of anxiety, worry, and mood associated with COVID-19. This specific survey had not previously been administered; questions were devised to collect information on mental health as it related to the COVID-19 pandemic in a timely manner. Some questions were modified from existing mental health surveys to fit the context of COVID-19 (14,15). Survey item responses were coded from –4 to +4 for this analysis. Responses “strongly agree” and “strongly disagree” were scored as +4 and –4, respectively, “agree” and “disagree” as +1 and –1, respectively, and “neutral” as 0. Responses to the question about feeling hopeful were reverse coded. This scale is consistent with the strength of the agreement/disagreement response being a quadratic function because we expected that choosing the “strongly” agree or disagree response reflected a substantially more pronounced feeling than choosing the agree or disagree response option. In a sensitivity analysis, we replaced +4 and –4 with +2 and –2, respectively (analogous to strength of response being a linear function). In another sensitivity analysis, we defined presence of any anxiety as responding “disagree” or “strongly disagree” to the question about feeling hopeful or “agree” or “strongly agree” to any of the other questions. Similarly, we derived presence of general anxiety, worry, and adverse mood using survey responses for questions within each respective subconstruct.

COVID-19 Mitigation Behaviors and Other Behaviors

Participants who reported access to a mask were asked how often in the past week they wore a mask; this was categorized into survey responses of “all of the time” or “less than all of the time.” Aligning with the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines at the time (16), participants were asked how often they remained at least 6 feet away from people who were not part of their household and whether they had traveled outside of their home (including outside of the state or outside the United States since the start of the pandemic). We asked whether, compared with before the pandemic, the participant’s physical activity level increased, decreased, or stayed the same; whether the participant’s weight increased, decreased, or stayed the same; and whether the participant’s eating habits changed. Full questions are provided in Supplemental Table 2.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

All covariates were collected or measured at the first CRIC study visit (2003–2008 in phase 1 and 2013–2015 in phase 3) or regular follow-up. At the first CRIC visit, participants self-reported sociodemographic information (education, employment status, health insurance, household income). At the first and follow-up visits, participants self-reported medical history, medication use, and lifestyle factors. In 2006–2008 for phase 1 and in 2013–2015 for phase 3, participants completed the Short Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults questionnaire (17).

Standard protocols were used to collect anthropometric measures, BP, and self-reported information. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease were self-reported annually. eGFR was calculated using the CRIC equation (18). Laboratory analyses were performed with stringent quality control at the CRIC Study Central Laboratory.

Statistical Analyses

Survey Analysis

Using responses to the statements in Supplemental Table 1, we derived composite scores for anxiety-related survey questions. Composite scores created for all questions collectively (referred to as overall global anxiety) were calculated by averaging responses for all questions. Composite scores for the subconstructs of general anxiety, worry, and mood/feelings were calculated by averaging survey responses for questions within each subconstruct. A higher summary score was indicative of stronger symptoms. To assess self-consistency of each composite score, we calculated Cronbach’s α for each summary subconstruct (19). We also examined correlations between each subconstruct.

Descriptive Statistics

We compared demographic and health characteristics among CRIC participants who did versus did not respond to the COVID-19 survey. Continuous variables are reported as mean and SD, and categorical variables are reported as number and percentage.

Modeling

Covariates used in models included those typically employed in analyses of CRIC data in the context of frequently analyzed outcomes, such as death or CKD progression. All models included age, sex, race and ethnicity, education, clinic site, employment status, health literacy, health insurance coverage, income, marital status, smoking status, presence of diabetes, presence of CVD, and eGFR. Demographic factors were measured at baseline. For all other factors, the most recent covariate value was used. We also adjusted for the difference in time between baseline CRIC visit and the date that the participants took the COVID survey.

Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression Related to COVID-19 Pandemic

Linear regression was used to look at the relationship of predictive factors of interest with overall global anxiety and with the three subconstruct scores. Logistic regression was used to look at the relationships of predictive factors of interest with presence of any anxiety, general anxiety, worry, and adverse mood.

COVID-19 Mitigation Behaviors and Other Behaviors

Logistic regression was used to examine associations between some health behaviors and anxiety, with questions including wearing a mask in public, staying 6 feet away from others, and traveling out of home state or country. Lastly, we examined associations of anxiety with questions assessing whether participants reported being less active than before the pandemic (compared with no change or being more active than before the pandemic), eating less healthy than before the pandemic (compared with no change or eating healthier than before the pandemic), and gaining weight since the start of the pandemic (compared with no change in weight or losing weight since the start of the pandemic). We examined association of overall anxiety and specific anxiety subconstructs with these outcomes. For analyses of specific anxiety subconstructs, we adjusted for other anxiety subconstructs.

Results

In total, 1873 individuals (66% of current CRIC participants) responded to a COVID-19 telephone survey from June to October 2020 (Table 1). Compared with survey nonresponders, those who responded were older, more likely to be women, had higher education, and were more likely to be non-Hispanic White. Compared with nonresponders, those who responded also had a lower prevalence of diabetes, hypertension, CVD, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and had less advanced CKD.

Table 1.

Comparison between CRIC COVID-19 survey participants and nonparticipants

| Characteristic | Participated in COVID-19 Survey (N=1873) | Eligible, but Did Not Participate in COVID-19 Survey (N=987) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 70±9.6 | 68±10.9 |

| Women | 872 (47) | 422 (43) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 253 (14) | 164 (17) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 728 (39) | 424 (43) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 849 (45) | 353 (36) |

| Other | 43 (2) | 46 (5) |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 275 (15) | 203 (21) |

| High school graduate | 306 (16) | 169 (17) |

| Some college | 518 (28) | 286 (29) |

| College graduate or higher | 773 (41) | 328 (33) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 32±7.2 | 31.8±7.8 |

| Diabetes | 997 (53) | 611 (62) |

| Hypertension | 1744 (93) | 955 (97) |

| History of CVD | 719 (38) | 502 (51) |

| History of COPD | 295 (16) | 205 (21) |

| eGFR (CRIC equation) | 53.1±20 | 35.3±23.5 |

| CKD stage | ||

| 2 (eGFR >60) | 651 (35) | 171 (17) |

| 3a (eGFR>45–60) | 524 (28) | 140 (14) |

| 3b (eGFR >30–45) | 454 (24) | 159 (16) |

| 4 (eGFR >15–30) | 216 (12) | 297 (30) |

| 5 (eGFR <15) | 22 (1) | 219 (22) |

| Days between eGFR and survey, median (min, max) | 356 (–89, 5688) | n/a |

Reported as mean±SD or n (%) unless indicated otherwise. Age at date of survey; education categorized as of CRIC entry; BMI, diabetes, hypertension, history of CVD and COPD, eGFR, and CKD stage, most recent value before survey date was used. CRIC, Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

The COVID-19 anxiety survey composite scores showed excellent self-consistency. Cronbach’s α was 0.87 for the set of question-specific scores (across all aforementioned domains) and 0.91 for scores (in this case, domain-specific averages) representing the general anxiety, worry, and mood subconstructs. Subconstructs were moderately to highly correlated with one another (ρ=0.66 for worry and general anxiety scores; ρ=0.63 for mood and general anxiety scores; and ρ=0.48 for worry and mood scores). As such, the three construct scores appear to be positively correlated but not duplicative of each other. The full correlation matrix for all questions is shown in Supplemental Table 3.

Overall, the most common response to the anxiety-related questions was “disagree,” with the majority of responses being either “disagree” or “strongly disagree.” The average overall global anxiety composite score was –0.83 (SD=1.15). For the general anxiety subconstruct, the average composite score was –1.21 (SD=1.4), and average scores were <0 for all questions; most participants disagreed or strongly disagreed with statements that they had a hard time sleeping or difficulty concentrating or were feeling overwhelmed because of COVID-19, or that they were anxious about seeing a doctor for health care unrelated to COVID-19 (Table 2). The average score for the subconstruct of worry was –0.48 (SD=1.39). For questions within this subconstruct, the average score was highest for worry about family or friends getting COVID-19, whereas participants were least worried about having enough food (Table 2). For the mood subconstruct, the average score was –0.96 (SD=1.23); average scores were <0 for all questions, with most participants feeling hopeful about the future and not reporting negative mood (Table 2).

Table 2.

Relative frequency of responses to anxiety-related questions in CRIC COVID-19 survey

| Anxiety Category | Question (Abridged) | SD | D | N | A | SA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General anxiety related to COVID-19 | Hard time sleeping | 549 (29) | 1118 (60) | 62 (3) | 109 (6) | 32 (2) |

| Difficulty concentrating | 504 (27) | 1146 (61) | 61 (3) | 133 (7) | 27 (1) | |

| Feeling overwhelmed | 361 (19) | 974 (52) | 106 (6) | 345 (18) | 85 (5) | |

| Anxious about seeing doctor | 296 (16) | 951 (51) | 89 (5) | 447 (24) | 87 (5) | |

| Worry | Very worried about getting COVID-19 | 175 (9) | 667 (36) | 161 (9) | 614 (33) | 254 (14) |

| Very worried: family/friends getting COVID-19 | 99 (5) | 408 (22) | 128 (7) | 884 (47) | 352 (19) | |

| Very worried about transmitting COVID-19 | 255 (14) | 778 (42) | 130 (7) | 502 (27) | 206 (11) | |

| Worried about money | 419 (22) | 1028 (55) | 62 (3) | 278 (15) | 84 (5) | |

| Worried about having enough food | 484 (26) | 1107 (59) | 43 (2) | 182 (10) | 54 (3) | |

| Worried about medical bills | 404 (22) | 993 (53) | 75 (4) | 287 (15) | 111 (6) | |

| Mood | Social distancing negatively affects mood | 359 (19) | 853 (46) | 139 (7) | 421 (23) | 99 (5) |

| Feeling alone and isolated | 394 (21) | 1011 (54) | 72 (4) | 338 (18) | 55 (3) | |

| Have felt depressed | 382 (20) | 977 (52) | 85 (5) | 367 (20) | 59 (3) | |

| Have felt hopeful about future | 50 (3) | 212 (11) | 201 (11) | 1138 (61) | 268 (14) |

Data shown as n (%). SD, strongly disagree; D, disagree; N, neutral; A, agree; SA, strongly agree; CRIC, Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort; COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019.

Results examining the associations between anxiety, patient factors, and health literacy are shown in Table 3. Age was negatively associated with overall scores of anxiety and the subconstructs of worry and mood. Being a woman, Hispanic ethnicity, and marginal and inadequate health literacy were also associated with higher overall anxiety composite score and at least one subconstruct score. Non-Hispanic Black participants had lower (better) mood scores than non-Hispanic White participants. Participants with a history of CVD had higher (worse) mood scores than those without a history of CVD. Higher household income at baseline visit was associated with lower anxiety in the composite survey score and worry and mood subconstruct scores.

Table 3.

Linear regression examining associations between patient factors, anxiety composite score, and anxiety survey subconstruct scores

| Factor | Overall Anxiety | General Anxiety | Worry | Mood |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (per 5 yr) | –0.06 (–0.09, –0.03)a | –0.04 (–0.08, 0)b | –0.08 (–0.12, –0.05)a | –0.05 (–0.09, –0.01)a |

| Women | 0.17 (0.06, 0.28)a | 0.32 (0.18, 0.45)a | 0.01 (–0.12, 0.14) | 0.27 (0.14, 0.39)a |

| Hispanic | 0.68 (0.44, 0.92)a | 0.9 (0.6, 1.2)a | 0.89 (0.6, 1.18)a | 0.13 (–0.14, 0.4) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.01 (–0.12, 0.13) | 0.06 (–0.09, 0.22) | 0.09 (–0.06, 0.24) | –0.17 (–0.31, –0.03)a |

| Other | 0.16 (–0.18, 0.51) | 0.25 (–0.18, 0.67) | 0.31 (–0.09, 0.72) | –0.14 (–0.53, 0.24) |

| Diabetes | 0.01 (–0.09, 0.12) | 0.04 (–0.09, 0.18) | –0.01 (–0.13, 0.12) | 0.01 (–0.11, 0.13) |

| CVD | 0.07 (–0.04, 0.17) | 0.01 (–0.13, 0.14) | 0.05 (–0.08, 0.18) | 0.15 (0.03, 0.27)a |

| eGFR (per 10 units) | 0 (–0.02, 0.03) | –0.01 (–0.04, 0.03) | 0.01 (–0.02, 0.04) | 0 (–0.03, 0.03) |

| Unemployed | 0.06 (–0.06, 0.18) | 0.04 (–0.1, 0.19) | 0.06 (–0.08, 0.2) | 0.06 (–0.07, 0.2) |

| Marginal health literacy | 0.33 (0.09, 0.57)a | 0.27 (–0.03, 0.56)b | 0.33 (0.04, 0.61)a | 0.41 (0.14, 0.68)a |

| Inadequate health literacy | 0.25 (0, 0.49)a | 0.29 (–0.02, 0.59)b | 0.18 (–0.11, 0.47) | 0.3 (0.02, 0.57)a |

| Medicaid health insurance | –0.06 (–0.24, 0.12) | –0.03 (–0.25, 0.19) | –0.05 (–0.27, 0.16) | –0.10 (–0.3, 0.1) |

| No health insurance | 0.12 (–0.19, 0.43) | –0.1 (–0.48, 0.28) | 0.31 (–0.05, 0.68)b | 0.04 (–0.3, 0.39) |

| Former smoker | 0.07 (–0.03, 0.18) | 0.06 (–0.07, 0.2) | 0.05 (–0.07, 0.18) | 0.12 (–0.01, 0.24)b |

| Current smoker | 0.15 (–0.08, 0.37) | 0.28 (–0.01, 0.56)b | 0.13 (–0.14, 0.4) | 0.04 (–0.21, 0.3) |

| Household income >$100K | –0.34 (–0.56, –0.13)a | –0.27 (–0.54, 0)b | –0.41 (–0.67, –0.15)a | –0.32 (–0.56, –0.07)a |

Betas reported. Adjusted for age at survey (integer), sex, race and ethnicity, education, clinical site, history of diabetes, history of any CVD, eGFR using CRIC equation, total metabolic equivalents score from physical activity, status of employment, functional health literacy, health insurance status, annual income, marital status, current smoker, and time from first CRIC visit to COVID-19 survey. Reference groups: non-Hispanic White for race and ethnicity, employed for unemployed, adequate for health literacy, other for health insurance, household income ≤20,000 for income. CVD, cardiovascular disease; CRIC, Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

P<0.05.

0.05≤P<0.1.

Table 4 shows the results of adjusted logistic regression models examining associations between behaviors (mask wearing, distancing, travel, eating habits, physical activity, and weight gain) and the composite score of overall global anxiety. Overall global anxiety was associated with 1.3 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.14 to 1.48) higher odds of mask wearing and 1.29 higher odds of eating less healthy, 1.32 higher odds of reduced physical activity, and 1.23 higher odds of weight gain (P<0.001 for all). Similar patterns were observed for the subconstructs, although the association between adverse mood and always wearing a mask was not significant (Table 4)

Table 4.

Adjusted logistic regression examining associations of overall anxiety composite score and subconstructs with behaviors

| Outcome (0=No; 1=Yes) | Overall Anxiety | General Anxiety | Worry | Mood | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (P Value) | (95% CI) | Odds Ratio (P Value) | (95% CI) | Odds Ratio (P Value) | (95% CI) | Odds Ratio (P Value) | (95% CI) | |

| Wearing mask: always | 1.3 (<0.001) | (1.14 to 1.48) | 1.2 (<0.001) | (1.08 to 1.34) | 1.28 (<0.001) | (1.15 to 1.43) | 1.1 (0.1) | (0.98 to 1.24) |

| Remaining 6 feet apart: always | 1.01 (0.83) | (0.92 to 1.11) | 1.05 (0.21) | (0.97 to 1.13) | 1.02 (0.61) | (0.94 to 1.11) | 0.94 (0.13) | (0.86 to 1.02) |

| Travel out of state/country | 0.97 (0.64) | (0.85 to 1.1) | 1.01 (0.79) | (0.91 to 1.13) | 0.93 (0.22) | (0.84 to 1.04) | 1.01 (0.88) | (0.9 to 1.13) |

| Eating less healthy | 1.29 (0.001) | (1.13 to 1.46) | 1.22 (≤0.001) | (1.1 to 1.35) | 1.15 (0.01) | (1.03 to 1.28) | 1.23 (<0.001) | (1.1 to 1.38) |

| Reduced physical activity | 1.32 (0.001) | (1.2 to 1.45) | 1.24 (<0.001) | (1.15 to 1.33) | 1.21 (<0.001) | (1.12 to 1.31) | 1.21 (<0.001) | (1.11 to 1.31) |

| Weight gain | 1.23 (0.001) | (1.11 to 1.38) | 1.15 (0.001) | (1.06 to 1.25) | 1.15 (0.002) | (1.05 to 1.26) | 1.19 (<0.001) | (1.08 to 1.3) |

Adjusted for age at survey (integer), sex, race and ethnicity, education, clinical site, history of diabetes, history of any CVD, eGFR using CRIC equation, total metabolic equivalents score from physical activity, status of employment, functional health literacy, health insurance status, annual income, marital status, current smoker, and time from first CRIC visit to COVID-19 survey. For analyses of the subconstructs, also adjusted for each of the other anxiety subconstruct scores. CVD, cardiovascular disease; CRIC, Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

In sensitivity analyses using the alternative linear approach to scoring strongly disagree and strongly agree as –2 and +2, respectively, patterns were similar, although some of the associations were less pronounced (Supplemental Table 4). The overall patterns of results were also similar for the presence of overall anxiety and presence of general anxiety, worry, or adverse mood, although some associations were attenuated (Supplemental Table 5).

Discussion

Prior research on anxiety among patients with CKD during the COVID-19 pandemic has been limited and most often focused on patients receiving hemodialysis (20, 21). This study provides information for future interventions that promote mental health and address anxiety in a population not well studied with respect to anxiety. COVID-19 has significantly increased stressors on patients with CKD, and we identified that 14% reported significant worry about contracting COVID-19 themselves, whereas 19% reported significant worry about their friends or family members contracting COVID-19. Although data are emerging related to predictors of anxiety and behavior change in the context of a pandemic, there are still gaps in what is known, and this study sheds light on both of these areas. Participants tended to report greater worry related to COVID-19 than general anxiety related to COVID-19 or adverse mood symptoms. Younger age, sex, Hispanic ethnicity, and limited health literacy were associated with higher anxiety. Further, our results suggest that anxiety is associated both with mask wearing, a desirable health behavior, and with less desirable lifestyle behaviors, such as less healthy food choices, reduced physical activity, and weight gain.

Several demographic groups that we identified as being associated with higher anxiety have also been previously identified to be at risk for other poor outcomes (22–25). In general, women are more likely to have anxiety disorders than men, and anxiety disorders may also be more disabling in women (26). A 2020 national survey of women found 49% had experienced new or worsening health-related socioeconomic risks since the start of the pandemic (27). In line with our findings of higher anxiety in those of Hispanic ethnicity, Hispanic adults in other studies have reported a higher prevalence of psychosocial stress related to not having enough food or stable housing (28).

We also identified that age is an important factor, although it is negatively associated with anxiety. Several studies in community-dwelling adults have found that during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, older adults may have been more resilient to anxiety, depression, and stress-related mental health effects compared with younger adults (29–33). Participants with a higher household income (>$100,000 per year versus ≤$20,000 per year) at baseline CRIC visit had lower scores on overall global anxiety, worry, and mood, which is perhaps unsurprising. National polls have found that individuals with a lower income tend to be more likely to report major negative mental health effects from worry or stress related to the pandemic than those with higher incomes (34).

Interestingly, compared with those with adequate health literacy, individuals with inadequate or marginal health literacy had higher scores on overall global anxiety, worry, and mood and marginally higher general anxiety scores. Prior literature on the association of health literacy with anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic has been limited; thus, this finding contributes to existing information on the many potential negative consequences or associations that limited health literacy can have on patients. Given the strong and consistent associations with multiple anxiety-related constructs in our analyses, further exploration of this topic is needed, including whether this association may be influenced by sources of health information. Interventions targeting health literacy may potentially improve mental health outcomes in the setting of public health emergencies.

We found higher levels of anxiety were associated with higher odds of always wearing masks while in public, although not with travel (outside of country or state) or staying 6 feet or more apart from those outside one’s household. Those with higher anxiety may simply feel a stronger resolve to use additional precautions against COVID-19, or perhaps wearing a mask causes one to feel higher level of anxiety in doing so. Regardless, this points to a need to support mask wearing without worsening anxiety.

Encouragingly, self-consistency for the global composite anxiety score and for each of the anxiety subconstructs was excellent. We also found strong correlations between the subconstructs, supporting that although there are distinct facets of what each is measuring, they do relate to each other in the context of an overarching domain, i.e., anxiety. Further work should evaluate whether there are similar correlation patterns between surveys and examine longitudinal changes because data are continuing to emerge from national US surveys of worsening mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. During the second quarter of 2019, one in ten US adults reported experiencing symptoms of anxiety, depression, or both, whereas more than one in three reported such symptoms during the second quarter of 2020 (35). Additionally, from August 2020 to February 2021, the percentage of adults with symptoms of anxiety or a depressive disorder increased from 36% to 42%; yet, very few reporting these symptoms received mental health counseling (36).

This study has several limitations. Although we do not have available information on what proportions of those who did not complete the survey refused the survey or were unable to be reached, COVID-19 survey respondents tended to be healthier than nonrespondents, and they may have had lower levels of anxiety. As the survey was administered early in the pandemic, we used a nonvalidated COVID-19 instrument; it is possible that some of the questions (e.g., the one on how social distancing affected mood) may have been challenging for people with lower health literacy to understand. Importantly, we found high self-consistency for the global composite score and subconstructs. We also found overall similar patterns of results in sensitivity analyses in which continuous scores were redefined and in which anxiety was categorized as presence of any anxiety. Anxiety questions were asked once per participant during the COVID-19 survey; so, we are not able to evaluate within-person changes in these measures as the pandemic progressed and new more contagious variants emerged. Additionally, we only had categorical information on changes in physical activity, weight gain, and eating behavior since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. These data were also collected before emergency use authorization of COVID-19 vaccines in the United States. Future work should evaluate such changes over time, after availability of COVID-19 vaccines and post pandemic. Due to the nature of the study design, there was varying time between the date of measurement of some baseline demographics (income, health insurance, and employment status) and clinical factors compared with the date of COVID-19 survey administration (median time from baseline visit and COVID-19 survey was 15.3 years for phase 1 and 5.9 years for phase 3). Although we adjusted for time between baseline CRIC visit and COVID-19 survey administration, these findings should be interpreted with caution.

In summary, this study is novel in its exploration of the relationship between patient factors, including health literacy, clinical factors, and behaviors with self-reported anxiety among a large cohort of participants with CKD during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our findings reinforce the importance of considering multiple aspects of anxiety and mental health both generally and when intervening to support patients during and after the pandemic. At-risk groups more affected also need tailored support to help them through crises, especially when faced with major alterations in how they interact with and rely on others during these times. More needs to be done to support virus mitigation strategies without provoking or worsening anxiety in patients with CKD, or worsening health behaviors, especially in those who are already at high risk of poor outcomes.

Disclosures

L.J. Appel reports honoraria from Wolters Kluwer and other interests or relationships with Bloomberg Philanthropies. D.L. Cohen reports consultancy for Medtronic, Metavention, Novartis, and Recor; ownership interest in Incyte and Kura (spouse); research funding from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study and Medtronic; honoraria from Medtronic, Metavention, Novartis, and Recor; patents or royalties from Incyte (spouse); and an advisory or leadership role for Kura (spouse). H.I. Feldman reports being an employee of Perleman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania; consultancy for InMed, Inc., Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co., Ltd. (ongoing), and the National Kidney Foundation (ongoing); and an advisory or leadership role for the American Journal of Kidney Disease (editor in chief), the CRIC Study (steering committee chair), and the National Kidney Foundation (member of the Advisory Board). J.P. Lash reports an advisory or leadership role for Kidney360. R.G. Nelson reports being an employee of the National Institutes of Health. M. Rahman reports consultancy for Barologics; research funding from Bayer Pharmaceuticals and Duke Clinical Research Institute; honoraria from Bayer, Reata, and Relypsa; and an advisory or leadership role for CJASN (associate editor) and the American Journal of Nephrology (editorial board member). P.S. Rao reports honoraria from AstraZeneca, and an advisory or leadership role for the AstraZeneca nephrology fellowship advisory board, GSK scientific advisory board, and the Renal Research Institute. S.J. Schrauben reports honoraria from Cowen and Company, LLC. J.A. Wright Nunes reports research funding as Co-I in a state-wide collaborative research with UM team and Blue Cross Blue Shield to improve kidney care across Michigan; a patent pending with others on a kidney model for display and kidney learning (no royalties and was derived from a project at UM); an advisory or leadership role with the American Kidney Fund (board), Medical Advisory Committee (chair), the CSN Program (chair), and Kidney Patient Education and Outreach (vice chair); and is funded by NIH R01 DK115844-01. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

Funding for the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Study was obtained under a cooperative agreement from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (grants U01DK060990, U01DK060984, U01DK061022, U01DK061021, U01DK061028, U01DK060980, U01DK060963, and U01DK060902). In addition, this work was supported in part by Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania Clinical and Translational Science award NIH/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) UL1TR000003, Johns Hopkins University grant UL1 TR-000424, University of Maryland General Clinical Research Center grant M01 RR-16500, the Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland grant UL1TR000439 from the NCATS component of the NIH and NIH roadmap for Medical Research, Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research grant UL1TR000433, University of Illinois at Chicago Clinical and Translational Science Award grant UL1RR029879, Tulane Center of Biomedical Research Excellence for Clinical and Translational Research in Cardiometabolic Diseases grant P20GM109036, Kaiser Permanente NIH/National Center for Research Resources University of California San Francisco Clinical and Translational Science Institute grant UL1 RR-024131, and the Department of Internal Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine grant NM R01DK119199. None of the funders of this study had any role in the current study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; or the decision to submit the report for publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants, investigators, and staff of the CRIC Study for their time and commitment. These findings were reported as an abstract at Kidney Week 2021 (Abstract PO0098).

Contributor Information

Collaborators: The CRIC Study Investigators, Lawrence J. Appel, Jing Chen, Debbie L. Cohen, Harold I. Feldman, Alan S. Go, James P. Lash, Robert G. Nelson, Mahboob Rahman, Panduranga S. Rao, Vallabh O. Shah, and Mark L. Unruh

Author Contributions

L.J. Appel, D.L. Cohen, K.S. Dorans, H.I. Feldman, J.P. Lash, R.G. Nelson, M. Rahman, P.S. Rao, D.E. Schaubel, S.J. Schrauben, D. Sha, and J.A. Wright Nunes were responsible for the investigation and reviewed and edited the manuscript; L.J. Appel, D.L. Cohen, K.S. Dorans, H.I. Feldman, J.P. Lash, R.G. Nelson, M. Rahman, P.S. Rao, D.E. Schaubel, S.J. Schrauben, and J.A. Wright Nunes were responsible for the conceptualization of the study; L.J. Appel, D.L. Cohen, K.S. Dorans, H.I. Feldman, J.P. Lash, R.G. Nelson, M. Rahman, D.E. Schaubel, S.J. Schrauben, D. Sha, and J.A. Wright Nunes were responsible for the methodology; L.J. Appel, H.I. Feldman, J.P. Lash, M. Rahman, and P.S. Rao were responsible for funding acquisition; K.S. Dorans, D.E. Schaubel, and J.A. Wright Nunes wrote the original draft of the manuscript; H.I. Feldman, D.E. Schaubel, and S.J. Schrauben were responsible for project administration; H.I. Feldman, M. Rahman, and D.E. Schaubel were responsible for supervision; J.P. Lash, M. Rahman, D.E. Schaubel, and D. Sha were responsible for data curation; D.E. Schaubel and D. Sha were responsible for formal analysis; D. Sha was responsible for software and visualization; and each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and agrees to be personally accountable for the individual’s own contributions and to ensure that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work, even one in which the author was not directly involved, are appropriately investigated and resolved, including with documentation in the literature if appropriate.

Data Sharing Statement

The data from the CRIC Study that support the findings of this study are available upon request at the NIDDK Repository at https://repository.niddk.nih.gov/studies/cric/.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://kidney360.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.34067/KID.0000222022/-/DCSupplemental.

Questions from Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) survey regarding symptoms of anxiety, worry, and mood. Download Supplemental Table 1, PDF file, 196 KB (195.2KB, pdf) .

Questions from CRIC COVID-19 survey regarding mitigation and other behaviors. Download Supplemental Table 2, PDF file, 196 KB (195.2KB, pdf) .

Correlation matrix of all COVID-19 anxiety questions. Download Supplemental Table 3, PDF file, 196 KB (195.2KB, pdf) .

Linear regression examining associations between patient factors, anxiety composite score, and anxiety survey subconstruct scores, with scores coded as linear functions. Download Supplemental Table 4, PDF file, 196 KB (195.2KB, pdf) .

Logistic regression examining associations between patient factors and odds of any overall anxiety and anxiety survey subconstruct. Download Supplemental Table 5, PDF file, 196 KB (195.2KB, pdf) .

References

- 1.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY: Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med 351: 1296–1305, 2004. 10.1056/NEJMoa041031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ku E, Xie D, Shlipak M, Hyre Anderson A, Chen J, Go AS, He J, Horwitz EJ, Rahman M, Ricardo AC, Sondheimer JH, Townsend RR, Hsu C: Change in measured GFR versus eGFR and CKD outcomes. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 2196–2204, 2016. 10.1681/ASN.2015040341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simões E Silva AC, Miranda AS, Rocha NP, Teixeira AL: Neuropsychiatric disorders in chronic kidney disease. Front Pharmacol 10: 932, 2019. 10.3389/fphar.2019.00932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang CW, Wee PH, Low LL, Koong YLA, Htay H, Fan Q, Foo WYM, Seng JJB: Prevalence and risk factors for elevated anxiety symptoms and anxiety disorders in chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 69: 27–40, 2021. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El-Gabalawy R, Mackenzie CS, Shooshtari S, Sareen J: Comorbid physical health conditions and anxiety disorders: A population-based exploration of prevalence and health outcomes among older adults. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 33: 556–564, 2011. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Porter AC, Lash JP, Xie D, Pan Q, DeLuca J, Kanthety R, Kusek JW, Lora CM, Nessel L, Ricardo AC, Wright Nunes J, Fischer MJ; CRIC Study Investigators : Predictors and outcomes of health-related quality of life in adults with CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1154–1162, 2016. 10.2215/CJN.09990915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grams ME, Surapaneni A, Appel LJ, Lash JP, Hsu J, Diamantidis CJ, Rosas SE, Fink JC, Scialla JJ, Sondheimer J, Hsu C-Y, Cheung AK, Jaar BG, Navaneethan S, Cohen DL, Schrauben S, Xie D, Rao P, Feldman HI; CRIC Study Investigators : Clinical events and patient-reported outcome measures during CKD progression: Findings from the CRIC study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 36: 1685–1693, 2021. 10.1093/ndt/gfaa364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torales J, O’Higgins M, Castaldelli-Maia JM, Ventriglio A: The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. Int J Soc Psychiatry 66: 317–320, 2020. 10.1177/0020764020915212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pakhchanian H, Raiker R, Mukherjee A, Khan A, Singh S, Chatterjee A: Outcomes of COVID-19 in CKD patients: A multicenter electronic medical record cohort study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 785–786, 2021. 10.2215/CJN.13820820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K, Bacon S, Bates C, Morton CE, Curtis HJ, Mehrkar A, Evans D, Inglesby P, Cockburn J, McDonald HI, MacKenna B, Tomlinson L, Douglas IJ, Rentsch CT, Mathur R, Wong AYS, Grieve R, Harrison D, Forbes H, Schultze A, Croker R, Parry J, Hester F, Harper S, Perera R, Evans SJW, Smeeth L, Goldacre B: Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature 584: 430–436, 2020. 10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feldman HI, Appel LJ, Chertow GM, Cifelli D, Cizman B, Daugirdas J, Fink JC, Franklin-Becker ED, Go AS, Hamm LL, He J, Hostetter T, Hsu CY, Jamerson K, Joffe M, Kusek JW, Landis JR, Lash JP, Miller ER, Mohler ER 3rd, Muntner P, Ojo AO, Rahman M, Townsend RR, Wright JT; Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study Investigators : The Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study: Design and methods. J Am Soc Nephrol 14[Suppl 2]: S148–S153, 2003. 10.1097/01.ASN.0000070149.78399.CE [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lash JP, Go AS, Appel LJ, He J, Ojo A, Rahman M, Townsend RR, Xie D, Cifelli D, Cohan J, Fink JC, Fischer MJ, Gadegbeku C, Hamm LL, Kusek JW, Landis JR, Narva A, Robinson N, Teal V, Feldman HI; Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study Group : Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study: Baseline characteristics and associations with kidney function. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 1302–1311, 2009. 10.2215/CJN.00070109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hannan M, Ansari S, Meza N, Anderson AH, Srivastava A, Waikar S, Charleston J, Weir MR, Taliercio J, Horwitz E, Saunders MR, Wolfrum K, Feldman HI, Lash JP, Ricardo AC; Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study Investigators : Risk Factors for CKD progression: Overview of findings from the CRIC Study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 648–659, 2021. 10.2215/CJN.07830520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B: A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 166: 1092–1097, 2006. 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB: The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 16: 606–613, 2001. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD) : Guidance for Unvaccinated People: How to Protect Yourself & Others. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fprevent-getting-sick%2Fsocial-distancing.html#stay6ft. Accessed July 3, 2021

- 17.Baker DW, Williams MV, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nurss J: Development of a brief test to measure functional health literacy. Patient Educ Couns 38: 33–42, 1999. 10.1016/S0738-3991(98)00116-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009. 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cronbach LJ: Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 16: 297–334, 1951. 10.1007/BF02310555 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee J, Steel J, Roumelioti M-E, Erickson S, Myaskovsky L, Yabes JG, Rollman BL, Weisbord S, Unruh M, Jhamb M: Psychosocial impact of COVID-19 pandemic on patients with end-stage kidney disease on hemodialysis. Kidney360 1: 1390–1397, 2020. 10.34067/KID.0004662020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang Z-H, Pan X-T, Chen Y, Wang L, Chen Q-X, Zhu Y, Zhu Y-J, Chen Y-X, Chen X-N: Psychological profiles of Chinese patients with hemodialysis during the panic of coronavirus disease 2019. Front Psychiatry 12: 616016, 2021. 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.616016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fischer MJ, Go AS, Lora CM, Ackerson L, Cohan J, Kusek JW, Mercado A, Ojo A, Ricardo AC, Rosen LK, Tao K, Xie D, Feldman HI, Lash JP: CKD in Hispanics: Baseline characteristics from the CRIC (Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort) and Hispanic-CRIC Studies. Am J Kidney Dis 58: 214–227, 2011. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saunders MR, Ricardo AC, Chen J, Anderson AH, Cedillo-Couvert EA, Fischer MJ, Hernandez-Rivera J, Hicken MT, Hsu JY, Zhang X, Hynes D, Jaar B, Kusek JW, Rao P, Feldman HI, Go AS, Lash JP; Investigators on behalf of the CRIC Study : Neighborhood socioeconomic status and risk of hospitalization in patients with chronic kidney disease: A chronic renal insufficiency cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore) 99: e21028, 2020. 10.1097/MD.0000000000021028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ricardo AC, Yang W, Lora CM, Gordon EJ, Diamantidis CJ, Ford V, Kusek JW, Lopez A, Lustigova E, Nessel L, Rosas SE, Steigerwalt S, Theurer J, Zhang X, Fischer MJ, Lash JP; CRIC Investigators : Limited health literacy is associated with low glomerular filtration in the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study. Clin Nephrol 81: 30–37, 2014. 10.5414/CN108062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schrauben SJ, Hsu JY, Wright Nunes J, Fischer MJ, Srivastava A, Chen J, Charleston J, Steigerwalt S, Tan TC, Fink JC, Ricardo AC, Lash JP, Wolf M, Feldman HI, Anderson AH; CRIC Study Investigators : Health behaviors in younger and older adults with CKD: Results from the CRIC Study. Kidney Int Rep 4: 80–93, 2018. 10.1016/j.ekir.2018.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McLean CP, Asnaani A, Litz BT, Hofmann SG: Gender differences in anxiety disorders: Prevalence, course of illness, comorbidity and burden of illness. J Psychiatr Res 45: 1027–1035, 2011. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindau ST, Makelarski JA, Boyd K, Doyle KE, Haider S, Kumar S, Lee NK, Pinkerton E, Tobin M, Vu M, Wroblewski KE, Lengyel E: Change in health-related socioeconomic risk factors and mental health during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic: A national survey of U.S. women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 30: 502–513, 2021. 10.1089/jwh.2020.8879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McKnight-Eily LR, Okoro CA, Strine TW, Verlenden J, Hollis ND, Njai R, Mitchell EW, Board A, Puddy R, Thomas C: Racial and ethnic disparities in the prevalence of stress and worry, mental health conditions, and increased substance use among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, April and May 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 70: 162–166, 2021. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7005a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vahia IV, Jeste DV, Reynolds CF 3rd: Older adults and the mental health effects of COVID-19. JAMA 324: 2253–2254, 2020. 10.1001/jama.2020.21753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Czeisler MÉ, Lane RI, Petrosky E, Wiley JF, Christensen A, Njai R, Weaver MD, Robbins R, Facer-Childs ER, Barger LK, Czeisler CA, Howard ME, Rajaratnam SMW: Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, June 24–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 69: 1049–1057, 2020. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.González-Sanguino C, Ausín B, Castellanos MÁ, Saiz J, López-Gómez A, Ugidos C, Muñoz M: Mental health consequences during the initial stage of the 2020 coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. Brain Behav Immun 87: 172–176, 2020. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klaiber P, Wen JH, DeLongis A, Sin NL: The ups and downs of daily life during COVID-19: Age differences in affect, stress, and positive events. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 76: e30–e37, 2021. 10.1093/geronb/gbaa096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Tilburg TG, Steinmetz S, Stolte E, van der Roest H, de Vries DH: Loneliness and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: A study among Dutch older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 76: e249–e255, 2020. 10.1093/geronb/gbaa111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Panchal N, Kamal R, Cox C, Garfield R: The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and Substance Use. Available at: https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/the-implications-of-covid-19-for-mental-health-and-substance-use/. Accessed June 9, 2022

- 35.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics : Anxiety and Depression: Household Pulse Survey. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/pulse/mental-health.htm. Accessed June 9, 2022

- 36.Vahratian A, Blumberg SJ, Terlizzi EP, Schiller JS: Symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorder and use of mental health care among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, August 2020–February 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 70: 490–494, 2021. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7013e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Questions from Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) survey regarding symptoms of anxiety, worry, and mood. Download Supplemental Table 1, PDF file, 196 KB (195.2KB, pdf) .

Questions from CRIC COVID-19 survey regarding mitigation and other behaviors. Download Supplemental Table 2, PDF file, 196 KB (195.2KB, pdf) .

Correlation matrix of all COVID-19 anxiety questions. Download Supplemental Table 3, PDF file, 196 KB (195.2KB, pdf) .

Linear regression examining associations between patient factors, anxiety composite score, and anxiety survey subconstruct scores, with scores coded as linear functions. Download Supplemental Table 4, PDF file, 196 KB (195.2KB, pdf) .

Logistic regression examining associations between patient factors and odds of any overall anxiety and anxiety survey subconstruct. Download Supplemental Table 5, PDF file, 196 KB (195.2KB, pdf) .