Country Profile

Ethiopia is a landlocked country located in the northeastern part of Africa, otherwise known as the Horn of Africa, and occupies an area of 1,104,300 km2. It shares boundaries with North and South Sudan on the west, Somalia and Djibouti in the east, Eritrea in the north and northwest, and Kenya in the south. According to World Bank data from 2020, Ethiopia has a population of 115 million people, making it the second most populous country in Africa. Ethiopia has a GDP per capita income of US$934.6 and an international poverty rate (income <$1.9/day) of 31% and is classified as a low-income country. Life expectancy at birth is reported to be 66.2 years (1).

Although Ethiopia’s major health problems are infectious diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis, HIV, and maternal and childhood illnesses, there is ample evidence to indicate that noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) are becoming important causes of morbidity and mortality (2–4). According to a nationwide survey conducted in 2015, using the World Health Organization NCD STEPS instrument, the prevalence of hypertension and diabetes was 16% and 3%, respectively, in the adult population aged 15–69 years (5).

Prevalence of Kidney Diseases

Studies from Africa indicate that CKD is quite prevalent in the adult population. According to the International Society of Nephrology’s Global Kidney Health Atlas, the prevalence of CKD in Africa was 6%, with prevalence rate ranging between 5% and 18% (6). There is a dearth of data on the prevalence of kidney diseases in general and CKD/ESKD in particular in Ethiopia. Limited hospital-based observational studies indicate that CKD is a common health problem in Ethiopia, with diabetes, hypertension, and glomerular diseases being the most important causes (7).

History of RRT in Ethiopia

RRT was first introduced in Ethiopia in the early 1980s, with a single public hospital providing hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis for patients with presumed AKI. Maintenance dialysis services became available in 2001, and the first kidney transplant was done in 2015 (7,8). An impressive increase in dialysis services, particularly private for-profit-units, has occurred in urban areas in the last decade.

Dialysis for AKI

Dialysis is not readily available to most Ethiopian patients with dialysis requiring AKI. Hypovolemia, glomerulonephritis, pregnancy-related AKI, and sepsis account for more than three quarters of the etiologies for dialysis requiring AKI in Ethiopia. The majority of these patients are young, with about two-thirds being younger than 40 years of age (9).

Dialysis for both adult and pediatric patients with AKI has received little attention. The very few government hospitals with dialysis units provide hemodialysis to patients with AKI. If patients continue to require dialysis beyond a predefined period, usually 4 weeks, they can only continue the dialysis in private units from an out-of-pocket payment.

Children requiring acute dialysis have very limited access to dialysis. Whereas older children are dialyzed in “adult” units, younger children cannot be dialyzed at all. Only one public hospital in the entire country provides peritoneal dialysis for younger kids with presumed AKI using improvised peritoneal dialysis fluids and catheters.

Maintenance Hemodialysis: An Expensive and Difficult-to-Access Service

Presently, hemodialysis is the only dialysis modality available in Ethiopia for patients with ESKD. There is no peritoneal dialysis service in the country. The vast majority of patients with ESKD either cannot afford or cannot access a dialysis service and end up receiving palliative care.

In a survey conducted for the purpose of this article in September 2021, there are a total of 35 hemodialysis units in Ethiopia. Eleven units are in government-run hospitals, where the federal or regional governments subsidize the cost. The remaining units are private for-profit units. Thirty-one units are based in either a hospital or a clinic, whereas the remaining four are stand-alone dialysis units. The number of patients in a center varies widely, ranging from 10 to 250, with a median of 22 (interquartile range 23). A total of 1132 patients are on hemodialysis, making the prevalence about ten per million population.

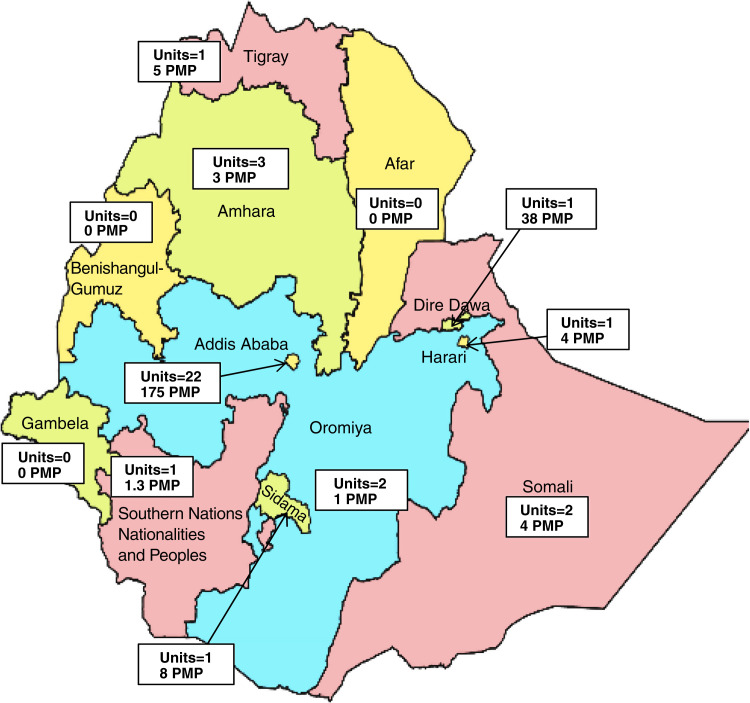

The majority of the dialysis centers and patients are concentrated in the capital city of Addis Ababa, where 23 of the 35 units (66%) and 77% of the patients receiving dialysis are located; however, the city accounts for only about 4% of the total population of the country. Most of the dialysis units outside the capital are also located in major urban areas, making them inaccessible for most of the population. Some regions do not have any dialysis services, even in their urban areas (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of hemodialysis units and prevalence per million population in the regions of Ethiopia.

The private sector is the major provider of services, catering for 79% of the prevalent patients on maintenance hemodialysis. This sector is challenged by the high cost of consumables and interruptions in the supply chain. It is also poorly regulated. A few public hospitals work in partnership with private companies in a public-private partnership (10).

Virtually all patients in the private sector pay out of pocket for all of the services. Excluding the cost of medications for comorbidities, anemia, and CKD-mineral and bone disorder treatment, the average cost of a single hemodialysis session in the private sector is 2300 Ethiopian birr (equivalent to US$51). For a patient who receives hemodialysis three times per week, the annual cost of hemodialysis alone is about US$8000. Contrasting this with the average per capita income of Ethiopians, which is estimated to be US$850, easily shows that maintenance hemodialysis is unaffordable to most Ethiopians. Most families face catastrophic health care expenditures when a family member starts maintenance hemodialysis. Health professionals and health administrators are faced with ethical challenges when they encounter patients with ESKD who need hemodialysis (10,11,12).

Due to the unbearable cost, more than half of prevalent hemodialysis patients cannot attend dialysis three times per week, with 48% and 9% of the patients attending twice and once per week, respectively.

Maintenance Hemodialysis Current Practice

The duration of a hemodialysis session in most units is 4 hours. A few units, accounting for 20% of the total, have a 3.5-hour session duration standard, and only one unit uses a 3-hour session duration. Arteriovenous fistula is the most commonly utilized vascular access, accounting for 72%. A sizable proportion (16%) of patients use temporary hemodialysis catheters, whereas the remaining 10% and 3% use tunneled hemodialysis catheters and arteriovenous grafts, respectively. In practice, we observe many patients with ESKD start dialysis as crash-landers on an emergency basis, making temporary catheter usage at the beginning quite common. The nurse-to-patient ratio in dialysis units is 4:1, and on average, patients are seen by a nephrologist once a month (Table 1).

Table 1.

Basic information on dialysis services in Ethiopia

| Number | Characteristic | n and/or % |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Total number of dialysis patients in the country | 1132 (around 10 pmp) |

| 2. | Number of patients on dialysis in the capital city | 875 (175 pmp) |

| 3. | Number of patients in private (for-profit) dialysis units | 892 (79%) |

| 4. | Total number of dialysis units | 35 |

| 5. | Hospital based versus freestanding units | 31 versus 4 (79% versus 21%) |

| 6. | Average cost of hemodialysis per session | US$51 |

| 7. | Modality of payment | Out of pocket |

| 8. | Staff who deliver dialysis | Dialysis nurses |

| 9. | Typical nurse-to-patient ratio | 1:4 |

| 10. | Length of dialysis sessions | 4 hr (77%), 3.5 hr (20%), 3 hr (3%) |

| 11. | Frequency of dialysis | 3×/wk (44%) |

| 2×/wk (48%) | ||

| 1×/wk (9%) | ||

| 12. | Proportion of dialysis units with a nephrologist | 69% |

| 13. | Frequency of nephrologist’s visit per month | At least once |

| 14. | Vascular access | AVF=72% |

| AVG=3% | ||

| Tunneled CVC=10% | ||

| Nontunneled CVC=16% |

pmp, per million population; AVF, arteriovenous fistula; AVG, arteriovenous graft; CVC, central venous catheter.

Kidney Transplantation in Ethiopia

There is one government-run national kidney transplant center in the country, which started its services in 2015. Between September 2015 and March 2020, 145 living-related donor kidney transplants were done in the center. The center has not done any transplants since March 2020.

The Nephrology Workforce

Ethiopia currently has 30 nephrologists (+13 trainees), giving a nephrologist-to-population ratio of 0.26 per million population; 80% of the nephrologists are based in the capital, leaving many of the regions without a single nephrologist. There are two nephrology fellowship training programs in the country. Whereas the first few nephrologists were trained abroad, the majority were trained locally.

There is no organized training program for dialysis nurses, but the nurses get on-the-job training and training provided by dialysis machine providing companies.

Renal Service: The Policy Vacuum in Ethiopia

The challenges to the provision of RRT in Ethiopia are quite daunting and range from policy issues to lack of resources. Despite public outcry for the provision of services, there is no national policy and strategy for renal care. Hence, renal care in Ethiopia exists in a policy vacuum. This has resulted in the inability of stakeholders to work in tandem. Services in a particular hospital or clinic start through the efforts of a single individual or a few individuals and are difficult to sustain. Provision of dialysis is largely left to the private sector, with almost all patients paying out of pocket. Dialysis centers operate with very little, if any, oversight, and one cannot even contemplate on enforcing minimum quality standards.

Prospects

On a more positive note, the Addis Ababa city administration and a few regional governments subsidize the cost of dialysis for patients dialyzing in the public dialysis units in their respective regions. In addition, the federal government’s attention to NCDs combined with public pressure for access to renal care will hopefully translate into a policy and strategy framework commensurate with the needs and means of the country. The increasing number of nephrologists and the availability of local training programs will provide additional impetus to the efforts to improve the care of patients with kidney diseases, including those who require RRT (Table 2).

Table 2.

Major challenges and prospects in the provision of dialysis in Ethiopia

| Challenges in the public sector |

| Lack of clear policy and strategy on kidney diseases in general and RRT in particular |

| Limited investment |

| Lack of sustainable funding |

| Limited or no access to dialysis in regions outside the capital |

| Challenges in the private for-profit sector |

| High cost of imported dialysis consumables |

| Interruptions in the supply chain |

| Poorly regulated quality of service |

| Lack of standard training for dialysis personnel |

| Unregulated and uncoordinated fundraising activities by commissioned fundraisers for only a few individual patients to fund their hemodialysis |

| Ethical challenges |

| Health care workers facing the challenge of caring for patients with dialysis requiring AKI with limited or no access to dialysis service |

| Most patients with ESKD, including those with life-threatening uremic emergencies, being left untreated |

| Prospects |

| A rapidly growing number of private for-profit dialysis facilities |

| Better attention being provided by the political leadership in the capital city and few regions |

Disclosures

All authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

None.

Acknowledgments

We thank the nephrologists and dialysis nurses who provided us with the data for the survey we conducted.

The content of this article reflects the personal experience and views of the authors and should not be considered medical advice or recommendation. The content does not reflect the views or opinions of the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) or Kidney360. Responsibility for the information and views expressed herein lies entirely with the authors.

Author Contributions

Y.T. Mengistu conceptualized the study and was responsible for the organization of data collection; A.M. Ejigu was responsible for data analysis; and both authors wrote the original draft of the manuscript, curated the data, and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

References

- 1.World Bank : Ethiopia. Available at: https://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/471041492188157207/mpo-eth.pdf. Accessed September 18, 2021

- 2.Shiferaw F, Letebo M, Misganaw A, Feleke Y, Gelibo T, Getachew T, Defar A, Assefa A, Bekele A, Amenu K, Teklie H, Tadele T, Taye G, Getnet M, Gonfa G, Bekele A, Kebede T, Yadeta D, GebreMichael M, Challa F, Girma Y, Mudie K, Guta M, Tadesse Y: Non-communicable diseases in Ethiopia: Disease burden, gaps in health care delivery and strategic directions. Ethiop J Health Dev 32: 1–12, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Misganaw A, Mariam DH, Ali A, Araya T: Epidemiology of major non-communicable diseases in Ethiopia: A systematic review. J Health Popul Nutr 32: 1–13, 2014 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ethiopia NCDI Commission : The Ethiopia Noncommunicable Diseases and Injuries (NCDI) Commission Report. Available at: http://www.ncdipoverty.org/ethiopia-report/. Accessed June 10, 2022

- 5.Gebreyes YF, Goshu DY, Geletew TK, Argefa TG, Zemedu TG, Lemu KA, Waka FC, Mengesha AB, Degefu FS, Deghebo AD, Wubie HT, Negeri MG, Tesema TT, Tessema YG, Regassa MG, Eba GG, Beyene MG, Yesu KM, Zeleke GT, Mengistu YT, Belayneh AB: Prevalence of high bloodpressure, hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, metabolic syndrome and their determinants in Ethiopia: Evidences from the National NCDs STEPS Survey, 2015. PLoS One 13: e0194819, 2018. 10.1371/journal.pone.0194819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oguejiofor F, Kiggundu DS, Bello AK, Swanepoel CR, Ashuntantang G, Jha V, Harris DCH, Levin A, Tonelli M, Niang A, Wearne N, Moloi MW, Ulasi I, Arogundade FA, Saad S, Zaidi D, Osman MA, Ye F, Lunney M, Olanrewaju TO, Ekrikpo U, Umeizudike TI, Abdu A, Nalado AM, Makusidi MA, Liman HM, Sakajiki A, Diongole HM, Khan M, Benghanem Gharbi M, Johnson DW, Okpechi IG; ISN Africa Regional Board : International Society of Nephrology Global Kidney Health Atlas: Structures, organization, and services for the management of kidney failure in Africa. Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 11: e11–e23, 2021. 10.1016/j.kisu.2021.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ejigu AM, Ahmed MM, Mengistu YT: Nephrology in Ethiopia. In: Nephrology Worldwide, edited by Moura-Neto JA, Divino-Filho JC, Ronco C, Geneva, Switzerland, Springer, 2020, pp 35–40 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmed MM, Tedla FM, Leichtman AB, Punch JD: Organ transplantation in Ethiopia. Transplantation 103: 449–451, 2019. 10.1097/TP.0000000000002551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ibrahim A, Ahmed MM, Kedir S, Bekele D: Clinical profile and outcome of patients with acute kidney injury requiring dialysis—An experience from a haemodialysis unit in a developing country. BMC Nephrol 17: 91, 2016. 10.1186/s12882-016-0313-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paltiel O, Berhe E, Aberha AH, Tequare MH, Balabanova D: A public-private partnership for dialysis provision in Ethiopia: A model for high-cost care in low-resource settings. Health Policy Plan 35: 1262–1267, 2020. 10.1093/heapol/czaa085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Global Burden of Disease 2020 Health Financing Collaborator Network : Tracking development assistance for health and for COVID-19: A review of development assistance, government, out-of-pocket, and other private spending on health for 204 countries and territories, 1990-2050. Lancet 398: 1317–1343, 2021. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01258-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luyckx VA, Miljeteig I, Ejigu AM, Moosa MR: Ethical challenges in the provision of dialysis in resource-constrained environments. Semin Nephrol 37: 273–286, 2017. 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2017.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]