Abstract

The ActII-ORF4 protein has been characterized as a DNA-binding protein that positively regulates the transcription of the actinorhodin biosynthetic genes. The target regions for the ActII-ORF4 protein were located within the act cluster. These regions, at high copy number, generate a nonproducer strain by in vivo titration of the regulator. The mutant phenotype could be made to revert with extra copies of the wild-type actII-ORF4 gene but not with the actII-ORF4-177 mutant. His-tagged recombinant wild-type ActII-ORF4 and mutant ActII-ORF4-177 proteins were purified from Escherichia coli cultures; both showed specific DNA-binding activity for the actVI-ORF1–ORFA and actIII-actI intergenic regions. DNase I footprinting assays clearly located the DNA-binding sites within the −35 regions of the corresponding promoters, showing the consensus sequence 5′-TCGAG-3′. Although both gene products (wild-type and mutant ActII-ORF4) showed DNA-binding activity, only the wild-type gene was capable of activating transcription of the act genes; thus, two basic functions can be differentiated within the regulatory protein: a specific DNA-binding activity and a transcriptional activation of the act biosynthetic genes.

Members of the genus Streptomyces are filamentous soil bacteria, and they produce about half of all known microbial antibiotics (4, 47). This genus also possess a complex life cycle, which includes morphological and physiological differentiation (11, 27). Antibiotic production usually begins at the transition phase between vegetative growth and the development of spore-bearing aerial mycelium, suggesting that there is a close relationship between the two processes antibiotic production and morphological differentiation (11).

Streptomyces coelicolor is an excellent model to study these process; it is the genetically most intensively studied Streptomyces species and produces four chemically different antibiotics, whose biosynthetic genes have been isolated: the blue-pigmented polyketide actinorhodin (65), undecylprodigiosin (42, 55), methylenomycin (12, 66), and the calcium-dependent antibiotic (14, 35, 37). There are extensive studies showing a close correlation between antibiotic production and other cellular processes, suggesting that control of antibiotic production might be operating on several levels. The first level includes genes which are implicated in antibiotic production and morphological differentiation, such as the bld genes (10, 25, 38, 46, 52), or those acting on the stringent response, such as relC (50) and relA (8, 44). A second level is represented by genes with pleiotropic effects on one or more antibiotic biosynthetic pathways, such as absA, absB (1, 6, 9), afsB (24), afsR (30), afsS (45), afsQ1 and afsQ2 (32), and ptpA (62). Finally the last level of this presumptive cascade of regulators is represented by the so called pathway-specific regulators, because mutations in these genes specifically affect only one antibiotic.

Several specific regulators for different biosynthetic pathways such as those for streptomycin (16), bialaphos (2), undecylprodigiosin (42, 49), cephamycin (51), and daunorubicin (59), have been identified in Streptomyces. For actinorhodin, the specific regulator, which was shown to be a positive regulator, was located in the central part of the act cluster (18) and assigned to the actII-ORF4 gene.

The amino acid sequence of ActII-ORF4 protein is very similar to the deduced products of the dnrI (59), redD (49), and ccaR (51) transcriptional activators and the N terminus of the AfsR protein (31) (37, 33, 25.9, and 34% identity, respectively). All of these proteins belong to an expanding family of regulatory proteins (SARPs) that possibly have a similar mechanism of transcriptional activation throughout DNA binding to specific nucleotides sequences (64). The dnrI gene can complement an actII-ORF4 mutation (59), but redD and ccaR cannot. Recent studies (60) have demonstrated that DnrI protein binds specifically to the promoter regions in the daunorubicin cluster and in this way controls the expression of many of the DNR biosynthetic genes. Nevertheless, the role of ActII-ORF4 protein as transcriptional regulator of the biosynthetic act genes is supported by indirect evidence (7, 22, 23, 44).

For further characterization of the actII-ORF4 gene product as transcriptional regulator, we overexpressed and purified the wild-type and mutant 177 (17) ActII-ORF4 proteins in Escherichia coli. This paper demonstrate that the positive regulator actII-ORF4 product is a DNA-binding protein that recognize specific regions of DNA within the act promoters.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and bacteriophages.

The E. coli strains used were JM101 (67) and BL21(DE3)pLysS (58). The Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) strains used were J1501 (hisA1 uraA1 strA1 pgl SCP1− SCP2−) (13) and JF1 (argA1 guaA1 redD42 actII-177 SCP1− SCP2−) (17). The Streptomyces lividans strain used was TK21 (str-6 SLP2− SLP3−) (29). E. coli and Streptomyces vectors are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Vectors and recombinant clones used in this study

| Vector | Relevant characteristicsa | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC18 | pBR322-derived E. coli vector; bla | 67 |

| pBR329 | E. coli general-purpose vector | 15 |

| pIJ2921 | pUC-derived E. coli vector with a modified polylinker; bla | 33 |

| pIJ2925 | pUC-derived E. coli vector with a modified polylinker; bla | 33 |

| pSU19 | pACYC184-derived E. coli vector; cat | 3 |

| pET-19b | pBR322-derived E. coli T7 polymerase expresion vector | (Novagen, Madison, Wis.) |

| pMV303 | KpnI-PstI fragment of actVI-ORF1–ORFA (nt 1406–2632) cloned in pSU19; cat | 20 |

| pMF1013 | SalI(11.8–13.3) fragment cloned in pIJ2925; carries the wild-type actII-ORF4 gene; bla | 18 |

| pMF2001.2 | NaeI-SmaI fragment (nt 1914–2231) of the actVI intergenic region, cloned in pIJ2925 (HincII site); bla | 20 |

| pMF2065 | 447-bp MboII fragment carrying the actIII-actI intergenic region, cloned in pIJ2925, bla | 19, 23 |

| pPAC2 | SphI-SacI fragment (positions 13.4–14.1) of the actIII-actI intergenic region, cloned in pIJ2925; bla | 19 |

| pPAC6 | Same as pMF1013; carries the actII-ORF4-177 gene from S. coelicolor JF1; bla | This work |

| pPAC10 | NdeI-BglII fragment carrying the recombinant wild-type actII-ORF4 gene cloned in pET-19b (NdeI-BamHI sites); bla | This work |

| pPAC14 | Same as pPAC10 but with the actII-ORF4-177 gene; bla | This work |

| Phage | ||

| M13mp18 | E. coli phage vector for DNA sequencing | 67 |

| Streptomyces | ||

| Plasmids | ||

| pIJ486 | High-copy-number pIJ101 derivative vector, tsr | 63 |

| pIJ80 | Unstable SCP2* derivative plasmid; neo | 60a |

| pIJ702 | High-copy-number vector; mel tsr | 34 |

| pIJ941 | Low-copy-number SCP2* derivative plasmid; tsr hyg | 40 |

| pMF1100 | SalI fragment (positions 11.8–13.3) cloned in pIJ941; carries the wild-type actII-ORF4 gene; hyg tsr | 18 |

| pMF1125 | SalI fragment (positions 11.8–13.3) cloned in pIJ702; carries the wild-type actII-ORF4 gene; tsr | This work |

| pMF1123 | EcoRI-HindIII fragment of pMF2001.2 cloned in pIJ486; tsr | This work |

| pMF1135 | EcoRI-HindIII fragment of pMF2065 cloned in pIJ486; tsr | This work |

| pPAS1 | BglII fragment of pPAC6 cloned in pPAS3; carries the actII-ORF4-177 gene; hyg | This work |

| pPAS3 | pIJ941-derivd vector with a frameshit within the thiostrepton resistance gene; hyg | 44 |

| pPAS4 | SalI fragment (positions 11.8–13.3) cloned in pPAS3; carries the wild-type actII-ORF4 gene; hyg | 44 |

| Phages | ||

| PM1 | φC31-derived vector; att− tsr hyg | 41 |

| φAB9 | BglII fragment from pMF1013 cloned in the BamHI-BglII sites of PM1; hyg | This work |

Abbreviations: bla, ampicillin resistance gene; cat, chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene; hyg, hygromicin resistsance gene; neo, neomycin resistance gene; tsr, thiostrepton resistance gene; mel, tyrosinase gene; nt, nucleotides.

Media, culture conditions, and microbiological procedures.

Streptomyces manipulations were as described previously (28). Thiostrepton (Sigma no. T-8902) was used at 50 μg/ml in agar medium and 10 μg/ml in broth cultures. Hygromycin B (Sigma no. H-2638) was used at 200 and 50 μg/ml in solid and liquid media, respectively. Neomycin (Sigma no. N-1876) was used at 12 μg/ml in solid media. E. coli was grown on Luria agar or in Luria broth (43), and transformants were selected with 50 μg of ampicillin per ml and 25 μg of chloramphenicol per ml.

DNA and RNA manipulations.

For isolation, cloning, and manipulation of nucleic acids, the methods used were those previously described for Streptomyces (28) and E. coli (43).

For high-resolution S1 assays, 0.08 pmol of 32Pi-labeled probe denatured at 65°C for 15 min was hybridized to 50 μg of total RNA as previously described (48). RNA was extracted from 3-day-old mycelium (28) grown on the surface of cellophane discs on R5 agar plates as previously described (39). For actI-ORF1, a 798-bp SphI-SacI fragment (positions 13.4 to 14.1 [19]) labeled at the 5′ end of the SacI site was used as a probe. For actVI-ORF1, the KpnI-BssHII fragment (nucleotides 1406 to 2252 [20]) was labeled at the 5′ end of the BssHII site. For actVI-ORFA, the CelII-SmaI fragment (nucleotides 1757 to 2231 [20]) was labeled at the 5′ end of the CelII site.

For DNA-binding assays with the actVI-ORF1–ORFA intergenic region, pMF2001.2 was digested with BamHI and end labeled with polynucleotide kinase and 50 pmol of [γ-32P]ATP (5,000 Ci mmol−1; Amersham). Then the DNA was digested with HindIII, and a 329-bp fragment was purified. For the actIII-actI intergenic region, pMF2065 was digested with HindIII and end-labeled with polynucleotide kinase as described above; a second digestion with XbaI gave the 450-bp fragment used as a probe. Shorter DNA fragments within these intergenic regions were generated by PCR (56). PCR mixtures consisted of 5 ng of pMF2001.2 or pMF2065 for the actVI-ORF1–ORFA or actIII-actI region, respectively, as templates, 20 pmol of primers G1 (5′-GGAAGCGCGGTGATGGTCAT-3′) and G39 (5′-GTGAACAGGTTGATCCATCCCAGG-3′) for the actVI-ORF1–ORFA region and primers G10 (5′-TTTGGGCGCCCGGCTCGAGC-3′) and G31 (5′-ATGACGACTCTGCGCTTCAATCCG-3′) for the actIII-actI region, 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and 1 U of Taq polymerase in a final volume of 50 μl, in the commercial buffer (Boehringer). The cycling conditions were 2 min of denaturation at 94°C; 30 cycles of denaturation (2 min at 90°C), annealing (1 min at 55°C), and extension (2 min at 72°C); and one cycle of 10 min at 72°C. The PCR-generated products, called F139 and F1031 for actVI-ORF1–ORFA and actIII-actI respectively, were purified from low-melting-temperature agarose. To prepare radiolabeled DNA fragments for gel mobility shift analysis and footprinting assays, primers were previously end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP (Amersham) and T4 polynucleotide kinase and then subjected to PCR amplification as described above.

Construction of S. coelicolor PM218.

For a further characterization of the role of the actII-ORF4 gene product as a transcriptional regulator, a strain with most of the act cluster deleted (including the regulatory region but leaving some act cluster deleted (including the regulatory region but leaving some act biosynthetic genes intact) was generated. As an additional advantage, this strain would not contain intermediates of the act pathway, which might affect the transcription of the actII-ORF4 or actII-ORF4-dependent genes. To construct this strain, the 4.4-kb BamHI (positions 1 to 3) and the 4.0-kb BamHI-BglII (positions 18 to 21) (41) fragments of the act cluster were ligated (in the same relative positions as they are located in the act cluster) within the BamHI site of pBR329. The resulting pBR329 derivative plasmid was linearized with EcoRI and ligated into the unique EcoRI site of pIJ941, and the ligation mixture was used to transform S. lividans TK21. The pIJ941 derivative carrying the recombinant pBR329 was selected by its hygromycin sensitivity. The resulting plasmid was finally introduced by transformation into S. coelicolor J1501, in which we expected that the deletion of the act cluster, cloned in the recombinant plasmid, would be transferred by homologous recombination into the chromosome. Colonies derived from a single crossover would carry an extra copy of actII-ORF4 and so might have an overproducing phenotype (18). A single colony with the predicted phenotype was isolated. The strain was cured for the pIJ941 derivative by introduction of pIJ80 (Table 1) after selection for its neomycin resistance marker. pIJ80 was then easily lost after growing the strain on R5 plates without selective pressure. The deletion in the act cluster was confirmed by Southern hybridization experiments (data not shown), and the strain was named S. coelicolor PM218. Few act genes are still present in this mutant: the actVI-ORFA, 1 and 2, a non-in-frame fusion between the truncated 5′ end of actVI-ORF3 and the 3′ end of actVII genes, and the complete actIV and actVB genes.

Isolation of actII-ORF4-177.

To isolate the actII-ORF4-177 gene, primers NdeI (5′-GGGGGCGCATATGAGATTC-3′) and BamHI (5′-CGCTGGATTTCCGGCGTCGGATCC-3′) were used in PCR amplifications of a 735-bp DNA fragment from the S. coelicolor JF1 chromosome under the conditions described above. The amplified fragment was cloned in an E. coli vector, and several clones were sequenced. The wild type PstI-BamHI fragment, internal to the actII-ORF4 gene (18) (from pMF1013), was replaced with that from the amplified fragment carrying the actII-177 mutation, yielding pPAC6 (see Table 1).

DNA sequencing.

DNA sequencing was carried out by the dideoxy-chain termination method (57) with the 7-deaza-dGTP reagent kit from U.S. Biochemical Corp. (no. 70750).

Cloning of actII-ORF4 in E. coli expression plasmids.

A NdeI site at translational start codon was generated by PCR with specific primers. The amplified fragment was cloned in the pIJ2921 vector, and the NdeI-BglII fragment carrying the whole gene was finally ligated into the NdeI-BamHI sites of pET-19b vector (Novagen), to give pPAC10. In this construction, the PstI(12)-BamHI(13) internal fragment (18) was replaced with the corresponding fragment from pPAC6, giving plasmid pPAC14, which carries the recombinant actII-ORF4-177 gene (Table 1).

Protein analysis.

Protein concentrations were determined by the method of Bradford (5). Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was performed by the method of Laemmli (36). Western blotting was carried out by transferring proteins to polyvinylidine difluoride (Immobilon-P; Millipore) membranes in 10mM CAPS buffer (pH 11) as is described previously (61). The immunodetection assay was performed with a monoclonal antibody raised against the His tag (Dianova) at a 1:1,000 dilution. A goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G peroxidase conjugate at a 1:1,000 dilution was used as the secondary antibody (Dako); the immunodetection assay mixture was processed with 4-chloro-1-naphthol and H2O2 as substrates.

Preparation of crude extracts from Streptomyces.

S. coelicolor PM218 containing pIJ702 vector or pMF1125 was grown in YEME medium (28) with 5 μg of thiostrepton per ml at 30°C with stirring at 250 rpm for 48 h. The cells were harvested, washed, and resuspended in TEG buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 0.5 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol, 50mM NaCl) plus 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Cells were disrupted by sonication, and cell debris was removed by centrifugation to yield the cell extract. Proteins in the cell extract were fractionated between 20 and 60% saturated ammonium sulfate, prepared in TEG buffer, and collected by centrifugation. The protein samples were dialyzed overnight at 4°C against TEG buffer and stored at −80°C until use.

Purification of the His-tagged ActII-ORF4 proteins from E. coli.

BL21(DE3)pLysS harboring plasmid pPAC10 or pPAC14 was grown at 37°C to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6; isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to a final concentration of 100 μM and incubated for 3.5 h at 28°C. Cells were harvested, washed with binding buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 1 M NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 0.1% Brij 36T, 100 mM imidazole) plus 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, resuspended in the same buffer, and disrupted by sonication. The cell lysate was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C in a Sorvall SS 34 rotor to remove the insoluble fraction. The supernatant containing the soluble His-tagged ActII-ORF4 protein was loaded on a Ni2+ chelating column (Invitrogen) and eluted with 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8)–100 mM NaCl–5 mM MgCl2–20% glycerol–0.1% Brij 36T–1 M imidazole–1 mM β-mercaptoethanol–0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The GroEL protein, which copurified with the recombinant ActII-ORF4 proteins, was removed by an additional wash, before the elution step, with binding buffer supplemented with 5 mM ATP. The eluted fractions containing the protein were pooled and dialyzed overnight against TEG buffer. Aliquots of the protein sample were stored at −80°C for DNA-binding assays. The purified ActII-ORF4 proteins (wild type and mutant) were unstable, and they lost most of the DNA-binding activity when stored at −80°C for 2 months. The wild-type and mutant ActII-ORF4 proteins behaved identically on the chromatography columns and showed the same purification pattern.

DNA-protein-binding assays.

For the gel mobility shift assays 0.6 to 0.9 μg of purified His-tagged protein was allow to stand for 10 min at 4°C in TEG buffer plus 70 mM KCl (final volume, 35 μl). Between 1 and 3 ng of end-labeled DNA fragments was finally added and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. For the supershift assays, the monoclonal antibody (0.3 μg) was preincubated with the proteins for 15 min at room temperature before the probe was added. Protein-bound and free DNA were applied on the loading buffer (10% glycerol, 0.5× TBE buffer [89 mM Tris (pH 8.3), 89 mM boric acid 2 mM EDTA], 0.05% bromphenol blue) to 4% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels and run in 0.5× TBE buffer. The gels were dried and exposed to Kodak X-ray film at −80°C. DNase I footprinting assays were performed essentially as described previously (21). These assays were carried out in 100 μl of the same reaction mixture described above for gel mobility shift assays. After incubation for 30 min at room temperature, 50 ng of DNase I (prepared in a solution containing 100 mM MgCl2 and 5 mM CaCl2) was added to each reaction mixture, and the mixtures were incubated for 3 min at room temperature, extracted with phenol, and then precipitated. The resulting pellet was resuspended in the sequencing loading buffer (U.S. Biochemical Corporation) and applied to an acrylamide-bisacrylamide (38:2)–40% urea sequencing gel along with dideoxy DNA sequencing ladders made with primers G1 and G39 for the actVI-ORF1–ORFA region and primers G10 and G31 for actIII-actI. After electrophoresis, the gels were dried and analyzed by autoradiography. In all DNA-protein-binding assays, the DNA-binding specificity was tested with 1 μg of poly(dI-dC)-(dI-dC) as a nonspecific competitor.

Computer analysis of sequences.

Protein secondary-structure prediction was made with the PHD program (53).

RESULTS

Cloning the actII-ORF4-177 gene.

The region of the act cluster which was genetically postulated as a regulatory region (actII) (54) for actinorhodin biosynthesis is physically located in the middle of the act cluster (41). One particular mutation (actII-177) was mapped on the 515-bp PstI-BamHI fragment (positions 12 to 13) which lies within the coding sequence of the actII-ORF4 gene (18). To gain insight into the structure-function relationship of the positive regulator, it was of interest to isolate this mutation for further characterization of the biological activity of its gene product. Thus, the PstI-BamHI fragment from S. coelicolor JF1 was cloned from the chromosome as described in Materials and Methods. The fragment showed that the actII-177 mutation carries a single change (C instead of T) at nucleotide 257 of the coding sequence of the actII-ORF4 gene (18), giving rise to a translated product with a change of a single amino acid (serine instead of leucine) at position 86 of the protein. No complementation was observed when this gene was introduced into the actII mutants (pPAS1), suggesting that the actII-ORF4-177 gene had lost the ability to induce expression of the act genes, and thus it would be useful in attempts to understand its role as a transcriptional regulator of the act biosynthetic genes.

The actII-ORF4 gene as transcriptional activator.

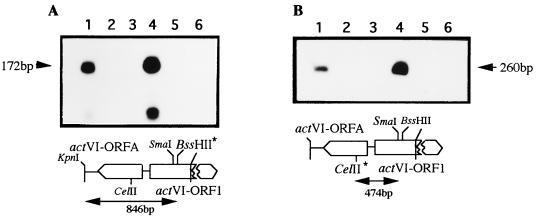

From genetics and DNA sequence analysis, it was suggested that transcription of the act genes might take place in a small number of polycistronic units and that it is presumably controlled by promoters located at the act intergenic regions (19, 20, 23, 41). To gain insight into the role of actII-ORF4 gene, we focused on one of these regions as a possible target for the ActII-ORF4 protein: the actVI-ORF1–ORFA (20) intergenic region. This region contains divergently arranged promoters for transcription of the actVI-ORFA and actVI-ORF1 genes. S. coelicolor PM218 was used for transcription determination of actVI-ORFA or actVI-ORF1, in either the presence or absence of the actII-ORF4 gene. Thus, S. coelicolor J1501 and PM218 (with most of the act cluster deleted, as indicated in Materials and Methods) were transformed with pPAS3 (control vector), pPAS4, or pPAS1 (carrying the actII-ORF4 and actII-ORF4-177 genes, respectively) (Table 1). Total RNA from all of them was extracted and hybridized with the corresponding probes. As shown in Fig. 1, S1 digestion-resistant fragments were observed only in the strains carrying the wild-type actII-ORF4 gene but not in S. coelicolor PM218 or in this strain carrying the actII-ORF4-177 gene, which gave similar results to the strain carrying the vector alone. When extra copies of the actII-ORF4 gene (strains carrying pPAS4) were present, the detected level of the S1-resistant fragments increased in relation to that obtained with the wild-type strain, suggesting that transcription of the act genes was enhanced by the actII-ORF4 gene. The actVI-ORF1 transcript was increased nearly twofold above the level of the wild-type strain, whereas that of actVI-ORFA was increased up to fivefold (Fig. 1). All these results strongly suggest that transcription of these act genes are clearly dependent on both the presence of the actII-ORF4 gene and its gene dose within the range of our experimental conditions.

FIG. 1.

High-resolution S1 mapping within the actVI-ORF1–ORFA intergenic region in S. coelicolor PM218. Transcriptional analysis of the actVI-ORF1 (A) and actVI-ORFA (B) genes is shown. The RNAs were extracted from the S. coelicolor strains: J1501 (lane 1), PM218 (lane 2), PM218 carrying pPAS3 as a control (lane 3), PM218 carrying the wild-type actII-ORF4 gene in pPAS4 (lane 4), PM218 carrying the actII-ORF4-177 gene in pPAS1 (lane 5), and E. coli tRNA as a control (lane 6). The probes, indicated by double-headed arrows, were the 846-bp KpnI-BssHII fragment (A) and the 474-bp CelII-SmaI fragment (B). The fragments were labeled at the positions indicated by the asterisks. Protected fragments of the expected size are indicated by arrows. As size marker, the HinfI-digested pBR329 was used.

The act intergenic regions as targets for the actII-ORF4 gene product. (i) In vivo titration of the actII-ORF4 gene product.

To clarify the possible role of the act intergenic regions as targets for the ActII-ORF4 protein, the actVI-ORF1–ORFA (20) and actIII-actI (19, 23) intergenic regions were cloned in the high-copy-number vector pIJ486. Thus, the 447-bp MboII fragment (19, 23), carrying the actIII and actI-ORF1 intergenic region, was blunt ended and cloned in the HincII site of pIJ2925 to yield pMF2065; the insert was recovered with EcoRI-HindIII double digestion and recloned into the EcoRI-HindIII sites of pIJ486, yielding pMF1135. In the same way, the 317-bp NaeI-SmaI fragment (nucleotides 1914 to 2231 [20]), carrying the actVI-ORF1–ORFA intergenic region, was cloned in the HincII site of E. coli vector pIJ2925 to yield pMF2001.2; then the insert was recloned into the EcoRI-HindIII sites of pIJ486 to give plasmid pMF1123. S. coelicolor J1501 was transformed with either pMF1135 or pMF1123; the transformants showed an actinorhodin-nonproducing phenotype, suggesting that a trans-acting element might be titrated in vivo by the cloned DNA. No changes were observed when the actII-ORF4 promoter region was present in high copy number (data not shown). When one extra copy of the actII-ORF4 gene was introduced in cis by using the att− recombinant phage φAB9 (Table 1), actinorhodin production was partially restored in transformants carrying pMF1135 but not in those carrying pMF1123. The wild-type phenotype was completely recovered when either strain was transformed with pPAS4 but not with the plasmid carrying the mutant actII-ORF4-177 gene (pPAS1), suggesting that the functional actII-ORF4 gene is needed for complete restoration of the wild-type phenotype.

All these results strongly suggest that (i) the actVI-ORF1–ORFA and actIII-actI intergenic regions in high copy number might titrate, in vivo, most of the free regulatory protein, thus preventing its interaction with the corresponding chromosomal regions, and (ii) this regulatory element may well be the actII-ORF4 gene product. If these assumptions are correct, a strong reduction in the transcription rate within both chromosomal intergenic regions, irrespective of which intercistron is present in high copy number, without affecting the actII-ORF4 transcription levels, might be expected.

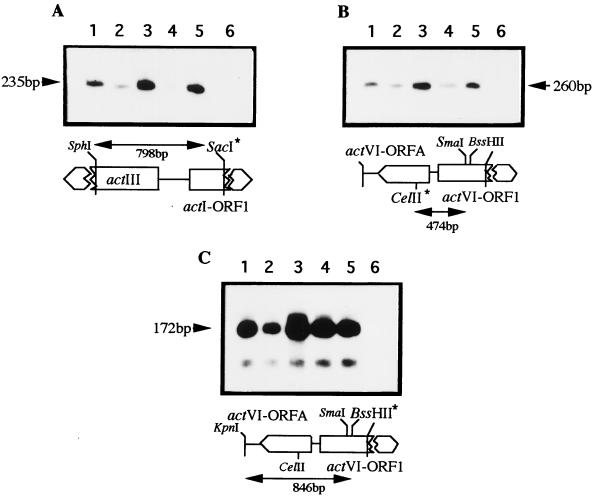

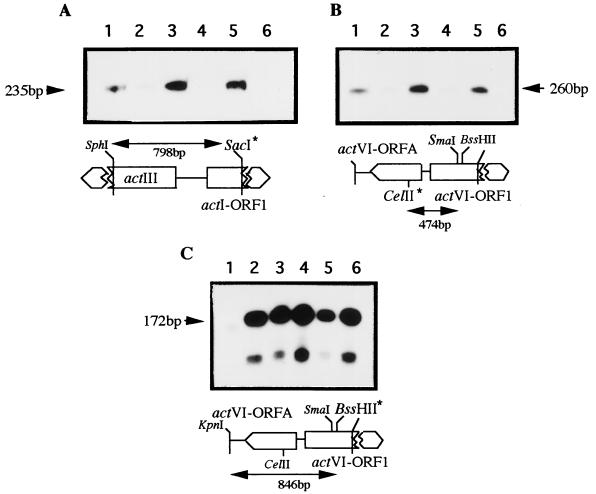

(ii) Transcriptional analysis of act biosynthetic genes in the recombinant mutants.

To confirm that the mutant phenotype was due to a reduced transcription of the act structural genes rather than a reduction of the actII-ORF4 transcription, two sets of S1-mapping experiments were carried out with RNA extracted from those mutants, with or without extra copies of either wild-type or mutant actII-ORF4 genes (Fig. 2 and 3). In the first set, transcription of the act structural genes was determined in those mutants generated with the actVI-ORF1–ORFA intergenic region in high copy number (Fig. 2). The detected transcription levels for actI-ORF1 (Fig. 2A) and actVI-ORFA (Fig. 2B) were only 25% of that of the control strains (S. coelicolor J1501 with or without pIJ486), while for the actVI-ORF1 gene (Fig. 2C), the detected transcription level was nearly 40% of that of the wild-type strains. When extra copies of the wild-type actII-ORF4 gene, but not the mutant gene, were introduced in these strains, the observed levels of actI-ORF1 and actVI-ORFA increased 3-fold whereas that of actVI-ORF1 was 1.5-fold higher than that of the control strain. In the second set of experiments, transcription levels were determined in mutants carrying the actIII-actI region in high copy number (Fig. 3). In these mutants, the transcription of the structural genes showed a different pattern: the levels of the actI-ORF1 (Fig. 3A) and actVI-ORFA (Fig. 3B) genes were similar to those in the previous mutants, whereas that of the actVI-ORF1 gene (Fig. 3C) showed no differences in any of these mutants. The levels of the actII-ORF4 transcripts were also determined on both recombinant mutants (data not shown) and proved to be unaffected in any of them. These results strongly suggest that the actinorhodin-nonproducing phenotype might well be due to a reduction of the amount of the free ActII-ORF4 protein (below the levels needed for activation of the act structural genes) rather than to a reduction of its transcription levels. With these data, it can be concluded that the ActII-ORF4 protein would probably be a DNA-binding protein whose targets could be located within the act intergenic regions.

FIG. 2.

Transcriptional analysis of some act genes in the recombinant strains carrying the actVI-ORF1–ORFA region in high copy number. Transcription was determined for the actI-ORF1 (A), actVI-ORFA (B), and actVI-ORF1 (C) genes. The RNAs were extracted from the following S. coelicolor strains: J1501 carrying pIJ486 as a control (lane 1); J1501 containing pMF1123, the actVI-ORF1–ORFA intergenic region, in high copy number (lane 2); the same strain carrying, in addition to pMF1123, the wild-type actII-ORF4 gene (lane 3) or the actII-ORF4-177 gene (lane 4) respectively, in the compatible plasmids pPAS4 or pPAS1; J1501 (lane 5); and E. coli tRNA as a control (lane 6). The probes and their respective sizes are indicated accordingly. The labeled positions are indicated by asterisks. The respective S1-protected fragments are indicated by arrows. The size markers are as in Fig. 1.

FIG. 3.

Transcriptional analysis of some act genes in the recombinant strains carrying the actIII-actI region in high copy number. Transcription was determined for the actI-ORF1 (A), actVI-ORFA (B), and actVI-ORF1 (C) genes. The RNAs were extracted from the following S. coelicolor strains: J1501 carrying pIJ486 as a control (lane 1); J1501 carrying pMF1135, the actIII-actI intergenic region, in high copy number (lane 2); the same strain carrying, in addition to pMF1135, the wild type actII-ORF4 gene (pPAS4) (lane 3) or the actII-ORF4-177 gene (pPAS1) (lane 4); J1501 (lane 5); and E. coli tRNA (lane 6) as a control. The probes were as in Fig. 2 and were labeled at the restriction site indicated by asterisks. The sizes of the protected fragments are indicated. The size markers are as in Fig. 1.

Overexpression of actII-ORF4 gene in S. coelicolor.

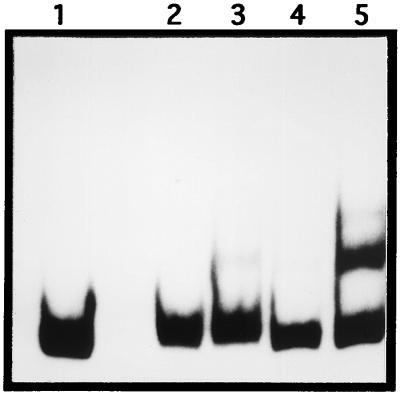

To test a possible DNA-binding activity related to the presence of the actII-ORF4 gene, S. coelicolor PM218 was transformed with a high copy number of actII-ORF4 gene (pMF1125) and with the control plasmid (pIJ702). In this strain we could overexpress the regulatory gene without overproduction of intermediates of the act biosynthetic pathway, thus avoiding a putative lethality. Cell extracts and fractions precipitated with ammonium sulfate were prepared from S. coelicolor PM218 harboring pMF1125 or pIJ702; these samples were used in gel mobility shift analysis with the actVI-ORF1–ORFA (20) (Fig. 4) and actIII-actI (19) (data not shown) intergenic regions as probes. DNA-binding activity was detected only with samples from S. coelicolor PM218 containing the actII-ORF4 gene (Fig. 4). Because the only difference between both strains is the presence of the regulator, we can concluded that the observed band shift might be due to the ActII-ORF4 protein.

FIG. 4.

Gel mobility shift analysis of the actVI-ORF1–ORFA intergenic region with crude extracts from Streptomyces. Lanes: 1, probe actVI-ORF1–ORFA intergenic region (329 bp); 2 and 4, cell extract and 60% ammonium sulfate precipitated from S. coelicolor PM218(pIJ702), respectively; 3 and 5, cell extract and 60% ammonium sulfate fraction from S. coelicolor PM218(pMF1125), respectively.

The enrichment of the DNA-binding activity observed within the 60% ammonium sulfate fraction could not be correlated with any protein with the expected size of ActII-ORF4, in Coomassie blue-stained gels. This suggest that the expressed level of the ActII-ORF4 might be low, although it is cloned in a high-copy-number vector. To overcome these additional difficulties, we decided to use E. coli to express and purify the regulatory protein.

Functional analysis of the ActII-ORF4 protein. (i) Purification of wild-type ActII-ORF4 and ActII-ORF4-177 proteins.

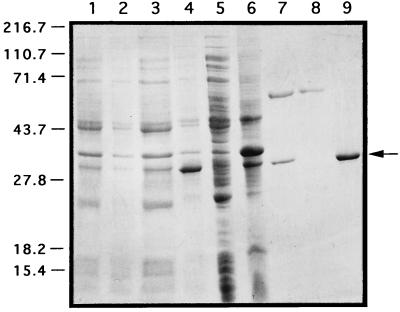

To overexpress the ActII-ORF4 protein in E. coli, the gene was cloned in the expression vector pET-19b (Novagen) to yield pPAC10 (see Materials and Methods) and used to transform E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS. In the same way, pPAC14 containing the actII-ORF4-177 gene from S. coelicolor JF1 was constructed. From the induced cultures, the proteins carrying the His tag fused at their N terminus were purified from the soluble fraction by Ni2+ affinity chromatography. The steps used in the purification of wild-type His-tagged ActII-ORF4 are shown in Fig. 5; the same purification pattern was obtained for the recombinant mutant protein (data not shown). Western blot analysis with a specific monoclonal antibody against the His tag epitope confirmed that the protein of 30.6 kDa from the eluted fractions was the recombinant His-tagged ActII-ORF4 protein (data not shown). The protein of 60 kDa that copurified with our proteins was end sequenced and shown to be the E. coli chaperon GroEL and was removed as in Materials and Methods (Fig. 5, lanes 8 and 9). As shown in lane 9, the ActII-ORF4 protein was purified almost to homogeneity.

FIG. 5.

Purification pattern of the wild-type His-tagged ActII-ORF4 protein. Lanes: 1 and 2, total-cell lysate of E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS/pET-19b not induced and induced, respectively; 3 and 4, total-cell lysate of E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS/pPAC10 not induced and induced, respectively; 5 and 6, soluble and insoluble fractions, respectively, from a cell extract of E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS/pPAC10; 7, fraction from a Ni2+ column eluted with 1 M imidazole; 8, fraction eluted with 0.1 M imidazole plus 5 mM ATP; 9, purified His-tagged ActII-ORF4 protein. Molecular masses are indicated in kilodaltons.

To find if the His-tagged fusion proteins were functional, we cloned the recombinant genes from plasmids pPAC10 and pPAC14 in Streptomyces vectors. The resulting plasmids were used to transform S. lividans TK21 and S. coelicolor JF1. Both strains harboring the recombinant wild-type actII-ORF4 gene in the low-copy-number vector, but not those harboring the mutant, showed an actinorhodin-producing phenotype, so that the recombinant gene was functional and complemented the mutation actII-177 of S. coelicolor JF1. Western blot analysis with the monoclonal anti-His tag antibody was carried out to confirm that the recombinant proteins were present.

(ii) Gel mobility shift assays with the recombinant proteins.

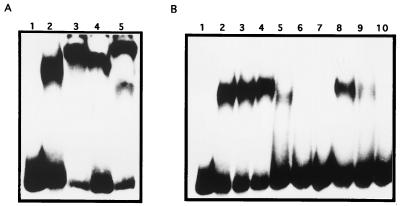

We next tested the ability of the purified ActII-ORF4 recombinant proteins to interact with specific regions of the act promoters. Gel mobility shift assays were initially carried out with probes consisting of those fragments which were previously tested in vivo as possible targets for such interaction. Thus, the actVI-ORF1–ORFA and actIII-actI intergenic regions were purified and end labeled (see Materials and Methods). Both proteins showed band shift activity with either fragments (data not shown). These probes were shortened to delimit the interacting regions by using PCR amplified fragments (see Materials and Methods). These smaller act regions still retain the band shift activity. Figure 6A shows that both wild-type and mutant His-tagged ActII-ORF4 proteins were interacting with the F139 fragment of the actVI-ORF1–ORFA region. The involvement of the recombinant proteins in the interaction was tested by a supershift assay involving the monoclonal anti-His tag antibody; in this case, a slower-running complex can be detected (Fig. 6A, lanes 3 and 5). The DNA-protein complexes with wild type and mutant proteins seemed to be different, as deduced from the differences in their mobilities. When the probe was the F1031 fragment, similar results were obtained (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

DNA-binding assays. (A) Gel mobility shift analysis of the actVI-ORF1–ORFA intergenic region and supershift assays. Lanes: 1, probe, F139 fragment (154 bp); 2, wild-type His-tagged ActII-ORF4 protein (0.7 μg); 3, wild-type His-tagged ActII-ORF4 protein (0.7 μg) plus anti-His tag antibody; 4, His-tagged ActII-ORF4-177 protein (0.7 μg); 5, His-tagged ActII-ORF4-177 protein (0.7 μg) plus anti-His tag antibody. (B) Cross-competitions in gel mobility shift analysis of the actVI-ORF1–ORFA intergenic region. Lanes: 1, probe, F139 fragment; 2, 3, and 4, His-tagged ActII-ORF4 protein (0.7, 0.8, and 0.9 μg, respectively); 5, 6, and 7, wild-type His-tagged ActII-ORF4 protein (0.9 μg) plus cold F139 fragment (50, 100, and 200 ng, respectively; 8, 9, and 10, wild-type His-tagged ActII-ORF4 protein (0.9 μg) plus cold F1031 fragment (50, 100, and 200 ng, respectively).

The relative affinities of ActII-ORF4 protein for either of the act regions were tested by gel mobility shift assays with the fragment F139 (Fig. 6B) or F1031 (data not shown) as the probe; cross-competitions for complexes formation were performed with equivalent amounts of the same unlabeled fragments. Providing that the two fragments are similar in size, the results of these assays showed that the wild-type recombinant ActII-ORF4 protein had higher affinity for the actVI-ORF1–ORFA than for the actIII-actI intergenic region, because more F1031 fragment was needed to compete the complex generated with the F139 fragment (Fig. 6B, lanes 5 and 8).

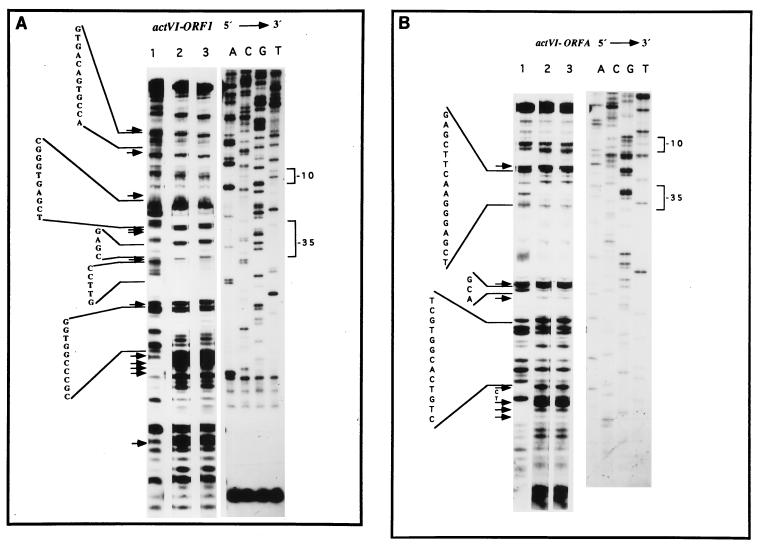

(iii) DNase I footprinting analysis.

To locate the sites of interaction between ActII-ORF4 and its targets of DNA, DNase I footprinting analysis were carried out (see Materials and Methods). When the fragment F139 (primer G1 5′-labeled) previously incubated in the presence or absence of the two His-tagged ActII-ORF4 recombinant proteins was digested with DNase I, five protected sites of the digestion were observed (Fig. 7A). The protected regions extended from about 4 to 12 bp and are flanked by multiples sites hypersensitive to DNase I digestion. Assays with the same fragment labeled in the complementary strand (Fig. 7B) gave three protected regions that extended from about 3 to 16 bp along the intergenic region. The protected regions were located close to the −10 and −35 regions of the promoters and in some cases overlapped them. Similarly, the actIII-actI intergenic region was also tested; unlike the actVI-ORF1–ORFA region, no clear protected sequences could be seen whereas well-defined hypersensitive regions were exhibited (data not shown). A summary of the results of the different footprinting assays with the actVI-ORF1–ORFA and actIII-actI intergenic regions are shown in Fig. 8A and B, respectively. There was no significant differences in the protected pattern with either the wild-type or mutant ActII-ORF4 proteins (Fig. 7A and B, lanes 2 and 3).

FIG. 7.

DNase I footprinting analysis in the actVI region. (A) Upper strand: F139 fragment 5′-labeled (G1 primer) as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Lower strand: F139 fragment 5′-labeled (G39 primer). Lanes: 1, probes; 2, wild-type His-tagged ActII-ORF4 protein (1.5 μg); 3, His-tagged ActII-ORF4-177 protein (1.5 μg). Sequencing reactions (ACGT) generated with the corresponding primers (G1 or G39) were run in parallel. The hypersensitive regions are indicated by arrows. The −10 and −35 regions of the promoters are indicated.

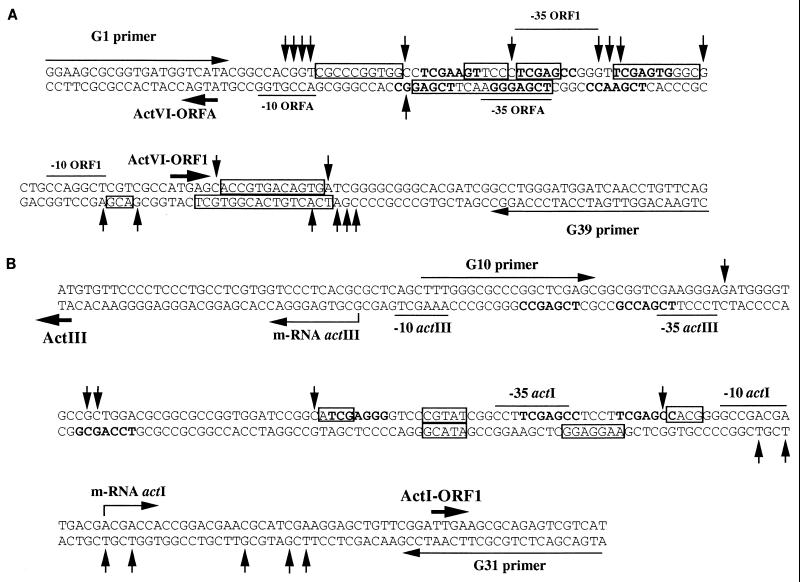

FIG. 8.

Summary of DNase I footprinting analysis for the actVI-ORF1–ORFA (A) and actIII-actI-ORF1 (B) intergenic regions. The transcriptional and translational start points from the act genes are indicated by thin and thick arrows, respectively. For the actVI-ORF1 and ORFA, transcriptional and translational start points are the same (20). Transcription start points for the actIII (23) and actI-ORF1 (50a) genes are also indicated, along with the −10 and −35 regions. The protected (boxes) and hypersensitive (vertical arrows) regions are marked in the sequence.

DISCUSSION

The role of the actII gene as regulator for actinorhodin biosynthesis was first suggested by Rudd and Hopwood (54) based on the phenotypic characteristics of their representative act mutants. Hallam et al. (23) showed that the expression of the actIII transcripts takes place only when the actII mutation is complemented with the wild-type actII region. When the DNA sequence of the actII region was determined, the actII mutation was located within the coding region of the so-called actII-ORF4, and strong evidence that its gene product was a putative transcriptional activator was provided (18). More recently, Gramajo et al. (22) showed that transcription of some act biosynthetic genes takes place after the actII-ORF4 transcripts reached their maximal levels; they suggested that the key feature for the onset of actinorhodin production in S. coelicolor would be the availability of the ActII-ORF4 protein for promoting activation of the act structural genes in the cells. In all cases, the nature of the actII-ORF4 gene product as a transcriptional regulator was supported only by circumstantial evidences. This work clearly demonstrates that the ActII-ORF4 protein is indeed a DNA-binding protein and activates the transcription of the act structural genes by specific interactions within the act promoters. Two regions of the act cluster were used for this experiment: the actIII-actI (19, 23) and the actVI-ORF1–ORFA (20) intergenic regions, which carry divergently arranged promoters for the “early”- and “late”-acting biosynthetic steps, respectively. The ActII-ORF4 protein could be titrated in vivo by increasing the copy number of its target sequences, thus generating a nonproducer strain; the mutant phenotype generated with the actIII-actI region could be easily reverted with one extra copy of the wild-type regulatory gene, while more copies are needed for reverting the nonproducer phenotype generated by the actVI-ORF1–ORFA intergenic region. These results suggest that in vivo, the affinity of the positive regulator for its target sequences seemed to be higher for the promoters of the “late”-acting genes than of the “early”-acting ones. This differential affinity can explain the higher transcription rate observed for the actVI genes than that for the actI genes. This higher expression might be important, because the gene products of the actVI genes (20) are involved in the so-called tailoring steps, leading to the production of several biologically active metabolites (54) and might well be susceptible to generation of oxidative stress. This effect can presumably be reduced by increasing the expression of the genes whose products might be involved in keeping the internal concentrations of such metabolites at a very low level. Alternatively, such putative active metabolites would be inducers for other transcriptional regulators, which finally will directly activate the transcription of these “late” act structural genes. This last possibility can be ruled out, because no differences were observed in the transcription patterns of these genes from those of the wild-type strain and S. coelicolor PM218 mutant (a strain with no such intermediates because the early-acting and most of the late-acting genes were removed).

Attempts to overexpress the ActII-ORF4 protein in Streptomyces were unsatisfactory. The gene was cloned in a high-copy-number vector, either with its own promoter or under the control of the tipA promoter (26); both systems yielded a very low level of the protein (as was the case for the DnrI protein [60]), even in S. coelicolor PM218, where accumulation of the act pathway intermediates is not possible. This low expression level could be due mainly to the presence in the actII-ORF4 gene of several unusual codons (18), which may be a bottleneck in the translation process, making the expression of this gene in Streptomyces very difficult for conventional protein purification. Because of these difficulties, the recombinant proteins (wild-type ActII-ORF4 and ActII-ORF4-177) were purified from E. coli cultures. Only the wild-type engineered protein complemented the actII-ORF4-177 mutation, suggesting that in vivo this recombinant protein behaved similarly to the wild type in activating the expression of the act structural genes. Although, most of the ActII-ORF4 proteins are expressed in E. coli as inclusion bodies, enough soluble protein was produced to allow their purification and functional characterization. The gel mobility shift assays showed that both purified proteins had a specific DNA-binding activity for the act intergenic regions. Competition experiments in these DNA-binding assays showed that the recombinant wild-type protein had higher affinity for the actVI-ORF1 than for the actI-ORF1 promoters, in good agreement with the results derived from in vivo titration; thus, we can conclude that the protein used in in vitro experiments is likely to be similar, at least in some biological properties, to that used in in vivo assays in Streptomyces.

The DNase I footprinting assays revealed some DNA sequences which are protected from the DNase I digestion. Although no large protected fragment were observed in any of the promoters tested, some regions with hypersensitivity to DNase I digestion can be observed; this footprinting pattern can be explained if the DNA-protein complexes had a short life or were relatively unstable. Some of the protected fragments or those flanked by hypersensitive regions within the actVI promoters overlap the imperfect repeated sequences 5′-TCGAG-3′, which were also protected by the DnrI protein in the daunorubicin biosynthetic cluster (60). This sequence is located near the −35 region of those promoters and is contained within the heptameric imperfect direct-repeat sequence 5′-TCGAGC(G/C)-3′, which was suggested by Wietzorrek and Bibb (64) to be the putative binding sites for the ActII-ORF4 and DnrI proteins. Despite this good correlation observed within the actVI promoters, this could not be established for the actIII-actI intergenic region under our experimental conditions, perhaps due to the lower affinity of the regulator for this region. It is noteworthy that a clear additional protected region was observed within the actVI-ORF1 transcript; although it does not overlap with the TCGAG sequence, this binding site might well be used for alternative transcriptional start points within the actVI polycistronic mRNA.

From all these, experiments we can conclude that the actII-ORF4 gene product is a DNA-binding protein. Recently, Wietzorrek and Bibb have suggested that the ActII-ORF4 protein (like other members of the SARP family) (64) contains the DNA-binding fold similar to the OmpR family and thus a helix-turn-helix motif. The mutation of the ActII-ORF4-177 protein (Ser instead of Leu at position 86) lies outside the helix-turn-helix motif and falls within the first predicted β-sheet (β6) (64), immediately after the putative DNA-binding fold; this might explain why the ActII-ORF4-177 protein still retains the specific DNA-binding activity. The β6-sheet is predicted to be partially buried (53), and the resulting change from a hydrophobic to another hydrophilic amino acid is likely to destroy this β-sheet structure; these changes could possibly generate an unstable protein, thus leading to a faster in vivo degradation. If the mutant protein is more easily degraded, it is possible that the protein never reaches the critical concentration needed for transcription activation; alternatively, it can be speculated that the generated changes prevent interactions between this transcriptional regulator and the RNA polymerase. In any case, the actII-177 mutation clearly demonstrates the existence of two different functions within the regulatory protein: specific DNA recognition and transcriptional activation. Isolation and characterization of additional mutations in the actII-ORF4 gene, will indeed be needed to generate more experimental data and a plausible model for transcriptional activation of the act structural genes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from Spanish CICYT (BIO96-1168-CC01-01) and European Union (BIO2-CT94-2067 and ERBCHRXCT940570).

We thank E. Montejo de Garcini, J. Ortín, and A. Nieto for helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adamidis T, Riggle P, Champness W. Mutations in a new Streptomyces coelicolor locus which globally block antibiotic biosynthesis but not sporulation. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:2962–2969. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.6.2962-2969.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anzai H, Murakami T, Imai S, Satoh A, Nagaoka K, Thompson C J. Transcriptional regulation of bialaphos biosynthesis in Streptomyces hygroscopicus. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:3482–3488. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.8.3482-3488.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartolomé B, Jubete Y, Martínez E, de la Cruz F. Construction and properties of a family of pACYC184-derived cloning vectors compatible with pBR322 and its derivatives. Gene. 1991;102:75–78. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90541-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bérdy J. New ways to obtain antibiotics. Chin J Antibiot. 1984;7:272–290. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brian P, Riggle F J, Santos R A, Champness W C. Global negative regulation of Streptomyces coelicolor antibiotic synthesis mediated by an absA-encoded putative signal transduction system. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3221–3231. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.11.3221-3231.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chakraburtty R, Bibb M. The ppGpp synthetase gene (relA) of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) plays a conditional role in antibiotic production and morphological differentiation. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5854–5861. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.18.5854-5861.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chakraburtty R, White J, Takano E, Bibb M. Cloning, characterization and disruption of a (p)ppGpp synthetase gene (relA) of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:357–368. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.390919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Champness W, Riggle P, Adamidis T. Loci involved in regulation of antibiotic synthesis. J Cell Biochem. 1990;14A:88. . (Abstract.) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Champness W C. New loci required for Streptomyces coelicolor morphological and physiological differentiation. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:1168–1174. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.3.1168-1174.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chater K F. Multilevel regulation of Streptomyces differentiation. Trends Genet. 1989;5:372–377. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(89)90172-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chater K F, Bruton C J. Resistance, regulatory and production genes for the antibiotic methylenomycin are clustered. EMBO J. 1985;4:1893–1897. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03866.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chater K F, Bruton C J, King A A, Suarez J E. The expression of Streptomyces and Escherichia coli drug-resistance determinants cloned into the Streptomyces phage φC31. Gene. 1982;19:21–32. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(82)90185-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chong P P, Podmore S M, Kieser H M, Redenbach M, Turgay K, Marahiel M, Hopwood D A, Smith C P. Physical identification of a chromosomal locus encoding biosynthetic genes for the lipopeptide calcium-dependent antibiotic (CDA) of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Microbiology. 1998;144:193–199. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-1-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Covarrubias L, Bolivar F. Construction and characterization of new cloning vehicles. VI. Plasmid pBR329, a new derivative of pBR328 lacking the 482-base-pair inverted duplication. Gene. 1982;17:79–89. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(82)90103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Distler J, Ebert A, Mansouri K, Pissowotzki K, Stockmann M, Piepersberg W. Gene cluster for streptomycin biosynthesis in Streptomyces griseus: nucleotide sequence of three genes and analysis of transcriptional activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:8041–8056. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.19.8041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feitelson J S, Hopwood D A. Cloning of a Streptomyces gene for an O-methyltransferase involved in antibiotic biosynthesis. Mol Gen Genet. 1983;190:394–398. doi: 10.1007/BF00331065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fernández-Moreno M A, Caballero J L, Hopwood D A, Malpartida F. The act cluster contains regulatory and antibiotic export genes, direct targets for translational control by the bldA tRNA gene of Streptomyces. Cell. 1991;66:769–780. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90120-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernández-Moreno M A, Martínez E, Boto L, Hopwood D A, Malpartida F. Nucleotide sequence and deduced function of a set of cotranscribed genes of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) including the polyketide synthase for the antibiotic actinorhodin. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:19278–19290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fernández-Moreno M A, Martinez E, Caballero J L, Ichinose K, Hopwood D A, Malpartida F. DNA sequence and functions of the actVI region of the actinorhodin biosynthetic gene cluster of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) J Biol Chem. 1994;269:24854–24863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galas D J, Schmiz A. DNase footprint: a simple method for the detection of protein-DNA binding specificity. Nucleic Acid Res. 1978;5:3157–3170. doi: 10.1093/nar/5.9.3157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gramajo H C, Takano E, Bibb M J. Stationary-phase production of the antibiotic actinorhodin in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) is transcriptionally regulated. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:837–845. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hallam S E, Malpartida F, Hopwood D A. Nucleotide sequence, transcription and deduced function of a gene involved in polyketide antibiotic synthesis in Streptomyces coelicolor. Gene. 1988;74:305–320. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90165-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hara O, Horinouchi S, Uozumi T, Beppu T. Genetic analysis of A-factor synthesis in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) and Streptomyces griseus. J Gen Microbiol. 1983;129:2939–2944. doi: 10.1099/00221287-129-9-2939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harasym M, Zhang L H, Chater K, Piret J. The Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) bldB region contains at least two genes involved in morphological development. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:1543–1550. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-8-1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holmes D J, Caso J L, Thompson C J. Autogenous transcriptional activation of a thiostrepton-induced gene in Streptomyces lividans. EMBO J. 1993;12:3183–3191. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05987.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hopwood D A. The Leeuwenhoek Lecture, 1987. Toward an understanding of gene switching in Streptomyces, the basis of sporulation and antibiotic production. Proc R Soc London Ser B. 1988;235:121–138. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1988.0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hopwood D A, Bibb M J, Chater K F, Kieser T, Bruton C J, Kieser H M, Lydiate D J, Smith C P, Ward J M, Schrempf H. Genetic manipulation of Streptomyces: a laboratory manual. Norwich, United Kingdom: The John Innes Foundation; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hopwood D A, Kieser T, Wright H M, Bibb M J. Plasmids, recombination and chromosome mapping in Streptomyces lividans 66. J Gen Microbiol. 1983;129:2257–2269. doi: 10.1099/00221287-129-7-2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horinouchi S, Hara O, Beppu T. Cloning of a pleiotropic gene that positively controls biosynthesis of A-factor, actinorhodin, and prodigiosin in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) and Streptomyces lividans. J Bacteriol. 1983;155:1238–1248. doi: 10.1128/jb.155.3.1238-1248.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horinouchi S, Kito M, Nishiyama M, Furuya K, Hong S K, Miyake K, Beppu T. Primary structure of AfsR, a global regulatory protein for secondary metabolite formation in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Gene. 1990;95:49–56. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90412-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ishizuka H, Horinouchi S, Kieser H M, Hopwood D A, Beppu T. A putative two-component regulatory system involved in secondary metabolism in Streptomyces spp. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7585–7594. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.23.7585-7594.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Janssen G R, Bibb M J. Derivatives of pUC18 that have BglII sites flanking a modified multiple cloning site and that retain the ability to identify recombinant clones by visual screening of Escherichia coli colonies. Gene. 1993;124:133–134. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90774-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katz E, Thompson C J, Hopwood D A. Cloning and expression of the tyrosinase gene from Streptomyces antibioticus in Streptomyces lividans. J Gen Microbiol. 1983;129:2703–2714. doi: 10.1099/00221287-129-9-2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kempter C, Kaiser D, Haag S, Nicholson G, Gnau V, Walk T, Gierling K H, Decker H, Zahner H, Jung G, Metzger J W. CDA: Calcium-dependent peptide antibiotics from Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) containing unusual residues. Angew Chem Int Ed English. 1997;36:498–501. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lakey J H, Lea E J, Rudd B A, Wright H M, Hopwood D A. A new channel-forming antibiotic from Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) which requires calcium for its activity. J Gen Microbiol. 1983;129:3565–3573. doi: 10.1099/00221287-129-12-3565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lawlor E J, Baylis H A, Chater K F. Pleiotropic morphological and antibiotic deficiencies result from mutations in a gene encoding a tRNA-like product in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Genes Dev. 1987;1:1305–1310. doi: 10.1101/gad.1.10.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leskiw B K, Mah R, Lawlor E J, Chater K F. Accumulation of bldA-specified transfer RNA is temporally regulated in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1995–2005. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.7.1995-2005.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lydiate D J, Malpartida F, Hopwood D A. The Streptomyces plasmid SCP2*: its functional analysis and development into useful cloning vectors. Gene. 1985;35:223–235. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malpartida F, Hopwood D A. Physical and genetic characterisation of the gene cluster for the antibiotic actinorhodin in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Mol Gen Genet. 1986;205:66–73. doi: 10.1007/BF02428033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malpartida F, Niemi J, Navarrete R, Hopwood D A. Cloning and expression in a heterologous host of the complete set of genes for biosynthesis of the Streptomyces coelicolor antibiotic undecylprodigiosin. Gene. 1990;93:91–99. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90141-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martínez-Costa O H, Arias P, Romero N M, Parro V, Mellado R P, Malpartida F. A relA/spoT homologous gene from Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) controls antibiotic biosynthetic genes. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10627–10634. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsumoto A, Ishizuka H, Beppu T, Horinouchi S. Involvement of a small ORF downstream of the afsR gene in the regulation of secondary metabolism in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Actinomycetologica. 1995;9:37–43. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Merrick M J. A morphological and genetic mapping study of bald colony mutants of Streptomyces coelicolor. J Gen Microbiol. 1976;96:299–315. doi: 10.1099/00221287-96-2-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miyadoh S. Research on antibiotic screening in Japan over the last decade: a producing microorganisms approach. Actinomycetologica. 1993;7:100–106. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murray G M G. Use of sodium trichloroacetate and mung bean nuclease to increase sensitivity and precision during transcript mapping. Anal Biochem. 1986;158:165–170. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(86)90605-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Narva K E, Feitelson J S. Nucleotide sequence and transcriptional analysis of the redD locus of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) J Bacteriol. 1990;172:326–333. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.1.326-333.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ochi K. A relaxed (rel) mutant of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) with a missing ribosomal protein lacks the ability to accumulate ppGpp, A-factor and prodigiosin. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:2405–2412. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-12-2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50a.Parro, V. Personal communication.

- 51.Pérez-Llarena F J, Liras P, Rodríguez García A, Martín J F. A regulatory gene (ccaR) required for cephamycin and clavulanic acid production in Streptomyces clavuligerus: amplification results in overproduction of both beta-lactam compounds. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2053–2059. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.6.2053-2059.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Puglia A M, Cappelletti E. A bald superfertile U.V.-resistant strain in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Microbiologica. 1984;7:263–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rost B. PHD: predicting one-dimensional protein structure by profile-based neural networks. Methods Enzymol. 1996;266:525–539. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)66033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rudd B A, Hopwood D A. Genetics of actinorhodin biosynthesis by Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) J Gen Microbiol. 1979;114:35–43. doi: 10.1099/00221287-114-1-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rudd B A, Hopwood D A. A pigmented mycelial antibiotic in Streptomyces coelicolor: control by a chromosomal gene cluster. J Gen Microbiol. 1980;119:333–340. doi: 10.1099/00221287-119-2-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saiki R K, Gelfand D H, Stoffel S, Scharf S J, Higuchi R, Horn G T, Mullis K B, Erlich H A. Primer directed enzymatic amplification of DNA with thermostable DNA polymerase. Science. 1988;239:487–491. doi: 10.1126/science.2448875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Studier W R, Moffatt B A. Use of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase to direct selective high-level expression of cloned genes. J Mol Biol. 1986;189:113–130. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stutzman-Engwall K J, Otten S L, Hutchinson C R. Regulation of secondary metabolism in Streptomyces spp. and overproduction of daunorubicin in Streptomyces peucetius. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:144–154. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.1.144-154.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tang L, Grimm A, Zhang Y X, Hutchinson C R. Purification and characterization of the DNA-binding protein DnrI, a transcriptional factor of daunorubicin biosynthesis in Streptomyces peucetius. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:801–813. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.01528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60a.Thompson, C. J. Personal communication.

- 61.Towbin H T, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Umeyama T, Tanabe Y, Aigle B D, Horinouchi S. Expression of the Streptomyces coelicolor a3(2) ptpA gene encoding a phosphotyrosine protein phosphatase leads to overproduction of secondary metabolites in Streptomyces lividans. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;144:177–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ward J M, Janssen G R, Kieser T, Bibb M J, Buttner M J, Bibb M J. Construction and characterisation of a series of multi-copy promoter-probe plasmid vectors for Streptomyces using the aminoglycoside phosphotransferase gene from Tn5 as indicator. Mol Gen Genet. 1986;203:468–478. doi: 10.1007/BF00422072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wietzorrek A, Bibb M. A novel family of proteins that regulates antibiotic production in streptomycetes appears to contain an OmpR-like DNA-binding fold. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:1181–1184. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5421903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wright L F, Hopwood D A. Actinorhodin is a chromosomally determined antibiotic in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) J Gen Microbiol. 1976;96:289–297. doi: 10.1099/00221287-96-2-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wright L F, Hopwood D A. Identification of the antibiotic determined by the SCP1 plasmid of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) J Gen Microbiol. 1976;95:96–106. doi: 10.1099/00221287-95-1-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 cloning vector and host strains: nucleotide sequences of M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]