Abstract

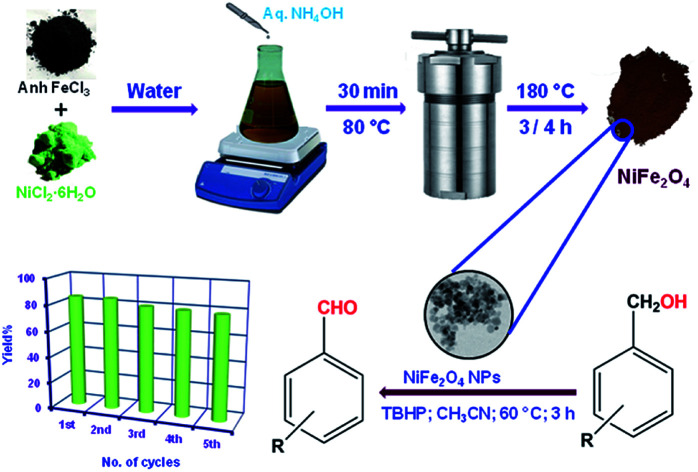

Benzaldehyde is one of the most important and versatile organic chemicals for industrial applications. This study explores a milder approach for the fabrication of NiFe2O4 nanoparticles (NPs) for use as a catalyst in the selective oxidation of benzyl alcohol to benzaldehyde. A co-precipitation method coupled with hydrothermal aging has been adopted to synthesize NiFe2O4 NPs in the absence of any additive. Different techniques such as electron microscopy, diffractometry, and photoelectron spectroscopy have been used to characterize the products. The results showed that the synthesized NiFe2O4 NPs are spherical, pure, and highly crystalline with sizes below 12 nm possessing superparamagnetic behaviour. The catalytic activity of the synthesized NiFe2O4 NPs has been assessed in the selective oxidation of benzyl alcohol under ambient reaction conditions. A conversion of 85% benzyl alcohol with 100% selectivity has been attained with t-butyl hydroperoxide at 60 °C in 3 h. With the optimized reaction conditions, the generality of the newly developed protocol has been expanded to a wide array of substituted benzyl alcohols with good performance. The NiFe2O4 nanocatalysts are magnetically separable and are reusable up to five cycles without loss of catalytic activity.

NiFe2O4 nanoparticles of well-controlled sizes have been synthesized for use as a catalyst in the selective oxidation of benzyl alcohol.

1. Introduction

Ferrites are categorized as electro-ceramics with ferromagnetic properties, mainly consisting of ferric oxide, α-Fe2O3.1 The general formula of ferrites is represented by (M1−xFex)A (MxFe2−x)BO4, where A and B represent tetrahedral and octahedral sites respectively.2 Magnetic ferrites are inverse spinel where the divalent ions occupy the octahedral sites and the trivalent ions occupy both the octahedral and tetrahedral sites giving rise to various magnetic behaviors.2 Both the structural and magnetic properties of ferrites vary depending on their sizes. Nickel ferrite (NiFe2O4) is a cubic ferrimagnetic oxide with an inverse structure where the divalent ion (Ni2+) occupies the octahedral sites and the trivalent ions (Fe3+) occupy both the tetrahedral and octahedral sites.3 The ferrimagnetism arises from the magnetic moment of the inverted spins present between the Fe3+ ions in the tetrahedral sites and Ni2+ ions in the octahedral sites.2 So, NiFe2O4 is considered as a soft ferromagnetic material.4 It is reported that when the diameter of the particle is less than that of a single magnetic domain, spinel ferrite nanoparticles (NPs) become superparamagnetic.4 Among different ferrites, spinel NiFe2O4 became a topic of interest in recent times because of its excellent technological applications.5–9 These technological applications motivated researchers to develop an efficient chemical technique to synthesize NiFe2O4 of controlled sizes and shapes. Among different chemical synthesis methods, the hydrothermal method is considered to be the most efficient because of various advantages associated with such techniques such as well-controlled particle size, morphology, and crystallinity. Also by changing the reaction time, pH of the reaction medium, and temperature, highly crystallized and weakly accumulated powders having narrow size distributions can be produced.10,11 Moreover, hydrothermal methods are simple, environment-friendly, and cost-effective.4,12 Accordingly, many researchers utilized the hydrothermal method under different reaction conditions to synthesize NiFe2O4 NPs. For example, Shen et al. reported the synthesis of highly ordered octahedral like NiFe2O4 with enhanced magnetic performance via a novel multistep hydrothermal approach at 180 °C for 8 h in the presence of ethylene glycol.13 Kesavan et al. synthesized NiFe2O4 NPs with a cubic crystal structure with an average crystallite size of 16 nm by a hydrothermal method at 130 °C for 12 h in the presence of polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) as an additive. They further calcined the isolated sample at 550 °C for 4 h to get the desired product.14 Safaei et al. presented a simple and efficient method to synthesize a magnetic NiFe2O4 nanocatalyst under hydrothermal conditions at 200 °C for 24 h using urea and polyethylene glycol (PEG) as additives.15 Paul et al. reported a novel and facile approach for the synthesis of spinel NiFe2O4 NPs employing homogeneous chemical precipitation followed by hydrothermal treatment using tributylamine (TBA) as a hydroxylating agent in the presence of PEG as a surfactant.16 Karaagac et al. synthesized NiFe2O4 NPs of different sizes and shapes in a two-step co-precipitation/hydrothermal process by varying the temperature between 125 and 200 °C for 40 h.17 Li et al. reported the synthesis of nanocrystalline NiFe2O4via a hydrothermal method at 160 °C for 6 h assisted with homogeneous co-precipitation at low temperatures in the presence of urea.18 There was no defined morphology and size of the formed NiFe2O4 nanocrystal. Rafique et al. reported the synthesis of NiFe2O4 nanooctahedra in the gram scale via a hydrothermal method at 220 °C for 12 h.19 Nejati et al. reported the synthesis of NiFe2O4 NPs by a hydrothermal method at different temperatures of 100, 130, and 150 °C for 18 h.20 They used triethylamine in ethyl acetate solution to adjust the pH of the reaction mixture. They further investigated the inhibition of the surfactant (glycerol or sodium dodecyl sulphate) on particle growth. Although the above reports were of successfully synthesized NiFe2O4 NPs, most of the reports utilized additives in the form of surfactants or polymers or the reaction was performed at higher temperatures or the reaction was continued for a long time. So, the processes are lengthy, energy-consuming, and in some cases complex due to the presence of additives. Hence, a mild and simple hydrothermal method of synthesis of uniform NiFe2O4 NPs without using any additive is highly desirable and is the current topic of research interest.

One of the most important and versatile organic chemicals in the chemical industry is benzaldehyde. It serves as a synthetic intermediate for agrochemicals, dyes, perfumery, and pharmaceuticals.21 It appears as the second most important aromatic molecule after vanillin used in the cosmetics and flavour industries.22,23 In commercial practice, benzaldehyde is commonly prepared by the partial oxidation of benzyl alcohol, alkaline hydrolysis of benzyl chloride, liquid-phase oxidation of toluene, and the carbonylation of benzene.24,25 However, the existence of a chlorinated product and low selectivity towards benzaldehyde are the main concerns of these processes.26 Another method to produce benzaldehyde is through the catalytic oxidation of styrene at the side chain.27 However, the harsh reaction conditions and complex and expensive methodologies implemented for the controlled conversion of styrene into one desired oxygenated product (selectivity issue) limit the applicability of this method. Therefore, many new routes have been introduced in recent years for the synthesis of benzaldehyde. One of the popular techniques is the catalytic oxidation of benzyl alcohol selectively using both homogeneous and heterogeneous catalyst systems.28 Although homogeneous systems were found to be successful, reusability, cost, sustainability, and toxicity issues limit their uses.28 Whereas, heterogeneous catalysts are in general more favourable than traditional homogeneous ones due to their promising easy separation and potential recycling. Subsequently, several heterogeneous catalyst systems were reported recently for the oxidation of benzyl alcohol with different oxidants. But satisfactory results in terms of selectivity were attained in only a few cases.29–34 Therefore, the demand for efficient and selective catalysts is the driving force for the researchers to synthesize new catalysts. Among different heterogeneous catalysts, magnetic ferrites occupied a significant position due to their easy recovery, low cost, and low toxicity. For example, Gawande et al. reported the use of recyclable Fe3O4–Co NPs for the oxidation of alcohols to carbonyl compounds using t-butyl hydroperoxide (TBHP) as the oxidant. They attained a conversion of 82% benzyl alcohol to benzaldehyde at 80 °C after 5 h.35 Saranya et al. reported the use of supported NiFe2O4 for the oxidation of benzyl alcohol in an acetonitrile medium at 80 °C using O2 as the oxidant. The conversion of benzyl alcohol reached a maximum of 77% with 100% selectivity.36 Sadri et al. reported the use of the magnetically separable nano-CoFe2O4 catalyst for oxidation of primary and secondary benzylic and aliphatic alcohols to produce the corresponding carbonyl products in water with oxone as the oxidizing agent at room temperature.37 Zhu et al. reported the use of CuFe2O4 as a catalyst for the oxidation of benzyl alcohol in the presence of TEMPO in water at 100 °C for 24 h using O2 as the oxidant. They recorded a maximum yield of 95%, which decreased when the amount of TEMPO was lowered.38 Bhat et al. reported the use of different ferrites for the oxidation of benzyl alcohol in an acetonitrile medium using H2O2 as an oxidant at 80 °C for 7 h. The maximum conversion of 82.4% was attained with a nanofunctionalized NiFe2O4 catalyst.39 Nasrollahzadeh et al. studied the performance of CoFe2O4 NPs in the oxidation of benzyl alcohol to benzaldehyde using H2O2 as an oxidant under solvent-free conditions. They acquired >99% conversion of benzyl alcohol to benzaldehyde at 110 °C for 5 h.40 A careful investigation suggests that in the above reports either the catalyst system was prepared using a complex methodology or harsh conditions such as high temperatures or longer reaction time was applied for the desired conversion. So, it is highly desirable to design and develop an efficient and mild protocol for the selective oxidation of benzyl alcohol to benzaldehyde. To address the above issues with the synthesis of ferrites and the selective oxidation of benzyl alcohol, the objective of the current investigation is (i) to synthesize uniform, easily separable, and cost-effective non-toxic catalysts easily and simply and (ii) to use the synthesized catalyst for selective oxidation of benzyl alcohol to benzaldehyde under mild reaction conditions. Subsequently, we were able to address some of the issues by synthesizing NiFe2O4 NPs via coprecipitation coupled with hydrothermal treatment in the absence of any additive or other toxic agents at a temperature of 180 °C for 3 h. We were able to produce highly crystalline, uniform particles. These particles successfully catalyze the oxidation of benzyl alcohol and its substituted derivative selectively under mild conditions. So, the objective of the research was accomplished with great success.

2. Experimental section

2.1. Chemicals

Anhydrous ferric chloride (FeCl3), nickel chloride hexahydrate (NiCl2·6H2O), benzyl alcohol (C6H5CH2OH), hydroquinone, and ammonium hydroxide (NH4OH; 25%) were purchased from Merck India. t-Butyl hydroperoxide (TBHP; 70% in water) and other substituted benzylic and aliphatic alcohols were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and Alfa-Aesar with the purity of 97–99%. All the reagents were used without further purification. All the glassware was cleaned in a bath of freshly prepared aqua-regia solution (HCl : HNO3 = 3 : 1 V/V) and then rinsed thoroughly with double distilled water. Double distilled water was used for all types of material preparation.

2.2. Synthesis of NiFe2O4 nanoparticles

To synthesize NiFe2O4, equal volume of aqueous NiCl2 (25 mL; 0.05 M) and FeCl3 (25 mL; 0.1 M) solution were taken in a round bottom (RB) flask fitted with a condenser and placed at 80 °C to get a Ni2+ to Fe3+ ratio of 1 : 2. The mixture of metal salt solutions was then subjected to constant stirring to get a homogeneous solution followed by the dropwise addition of aqueous NH4OH (5.25 M; 20 mL) solution. The reaction mixture was stirred for 30 min at the same temperature. The color of the reaction mixture gradually changed and finally, a reddish-brown precipitate was noticed. The whole reaction mixture was then transferred into a 100 mL Teflon lined autoclave and aged for 3 h at 180 °C. After that, the reactor containing the product was allowed to cool down to room temperature naturally. The solid precipitate was collected by magnetic separation using a simple bar magnet. The isolated solid product was purified by washing with H2O several times till a pH of 7.0 was obtained and finally dried in a vacuum at 60 °C for 12 h. This sample was labelled as NiFe2O4-3. Another set of the reaction was carried out by changing the hydrothermal aging time to 4 h keeping all the reaction conditions the same as the previous one and the sample was denoted as NiFe2O4-4. The synthesized particles were characterized by different spectroscopic, microscopic, and diffractometric techniques as discussed in detail in the ESI.†

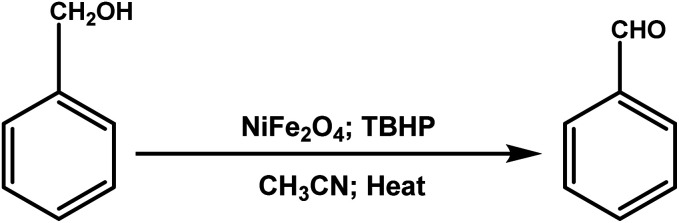

2.3. General procedure for the oxidation of benzyl alcohol

For the oxidation reaction, 10 mg of NiFe2O4 NPs (0.04 mmol; sample NiFe2O4-3) was added to 3 mL of acetonitrile taken in a clean dry round bottom flask of volume 10 mL. For the efficient dissolution of the catalyst, the mixture was sonicated for about 5 min. Following this, 0.104 mL benzyl alcohol (1 mmol) and 0.05 mL of 70% TBHP (0.4 mmol) was added to the reaction mixture and was subjected to magnetic stirring at 60 °C under reflux conditions. The progress of the reaction was monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC). After the complete conversion of the reaction, the reaction mixture was allowed to cool to room temperature and the catalyst was separated using a simple bar magnet. The reaction mixture was then diluted with an optimum amount of ethyl acetate and water. The organic layer was separated and washed with brine and dried over Na2SO4. The solvent was removed in a rotary evaporator (Buchi) under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (5% ethyl acetate in hexane) on silica gel (100–200 mesh) to get the desired product. The products were identified by 1H NMR and 13C NMR.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. X-ray diffraction study

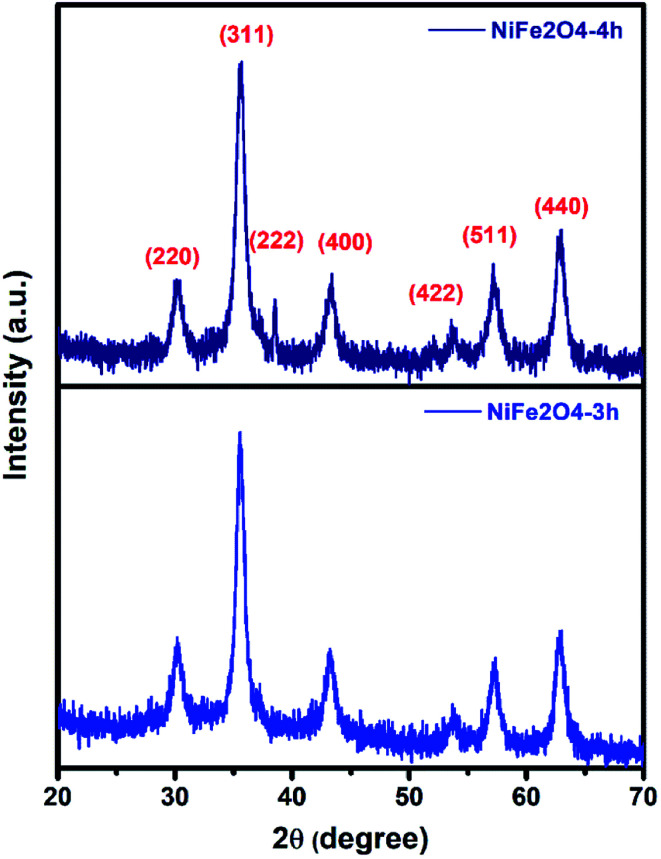

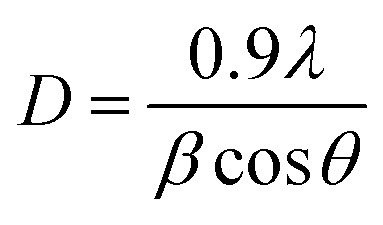

Fig. 1 shows the X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of the as-prepared samples. The diffractogram showed diffraction peaks at 2θ = 30.1, 35.6, 37.2, 43.2, 53.7, 57.1, and 62.7° which are assigned to (220), (311), (222), (400), (422), (511), and (440) planes of cubic structures of spinel NiFe2O4 (JCPDS Card no. 10-0325).41 No additional diffraction peaks due to impurities were noticed in the XRD pattern indicating the formation of pure and highly crystalline spinel NiFe2O4. Similar XRD results were reported earlier for both spherical and sheet-like NiFe2O4 NPs.4,42 The average crystallite size as measured using Scherer's equation (eqn (1)) was found to be 8.2 nm for both the samples.

|

1 |

where λ is the wavelength of the X-ray radiation (0.154 nm), θ is the diffraction angle and β is the full width at half maximum (FWHM).

Fig. 1. XRD patterns of NiFe2O4 NPs prepared at the hydrothermal aging time of 3 and 4 h.

3.2. Electron microscopy study

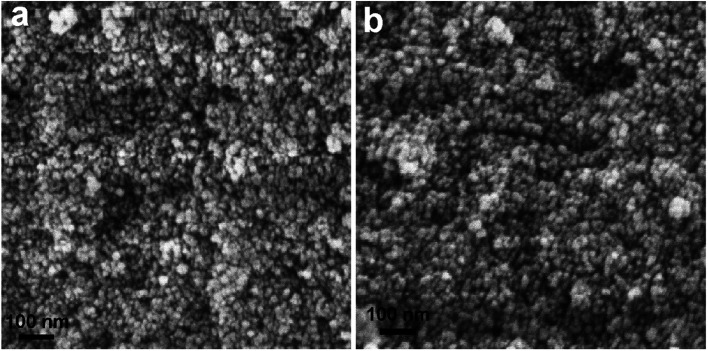

To examine the morphological evolution, we recorded the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the samples. Fig. 2a shows the SEM image of sample NiFe2O4-3 prepared at the hydrothermal aging time of 3 h, which is dominated by highly populated spherical particles of sizes below 15 nm. The SEM image of NiFe2O4-4 prepared at the hydrothermal aging time of 4 h also shows similar morphology and sizes. This might indicate that the hydrothermal aging time does not have much influence on the morphology and size of the products. Srivastava et al. also reported the formation of spherical NiFe2O4 NPs of sizes 15–20 nm by a hydrothermal method at 160 °C for 15 h.4 Abu-Dief et al. reported the synthesis of spherical NiFe2O4 NPs of an average size of 5 nm by the hydrothermal method at 180 °C for 24 h in presence of PEG.8 Ganesh et al. observed the formation of clusters of sheets of NiFe2O4 of average crystallite size of 16 nm from the respective salts in an aqueous medium by a hydrothermal method performed at 130 °C for 12 h in presence of PVP.42 The comparison of the results indicated that in the absence of any additive, nearly monodisperse NiFe2O4 NPs can be obtained within a shorter time. The energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy analysis confirmed the presence of elemental Ni, Fe, and O in the atomic ratio of approximately 1 : 2 : 4 in both the samples (Fig. S1 in the ESI†).

Fig. 2. FESEM images of the as-prepared NiFe2O4 NPs: (a) sample NiFe2O4-3 and (b) sample NiFe2O4-4.

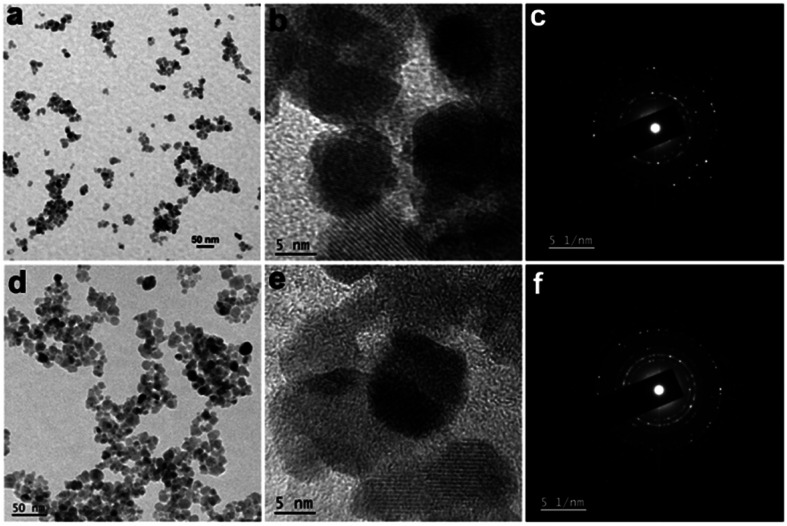

Further to study the morphological evolution, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were recorded from the samples. The TEM image recorded from sample NiFe2O4-3 (Fig. 3a) further confirmed the presence of spherical NPs those are mostly aggregated. This might be due to the absence of any stabilizer or magnetic properties of the particles. The high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) image recorded from a portion (Fig. 3b) showed the presence of well-resolved lattice fringes with a d space value of 0.3 nm. This value corresponds to the (220) lattice plane in NiFe2O4. The selected area electron diffraction (SAED) study (Fig. 3c) revealed the presence of bright spots superimposed on a ring pattern confirming that the NiFe2O4 NPs are polycrystalline. The TEM image recorded from sample NiFe2O4-4 (Fig. 3d) also shows similar structural evolution as observed in sample NiFe2O4-3. In this case, the particles are more uniform compared to the previous one. The HRTEM image and SAED pattern also show similar characteristics as observed in sample NiFe2O4-3. The mean size of NiFe2O4 NPs for both the samples was calculated from TEM micrographs considering 100 particles (Fig. S2 in the ESI†). The mean sizes of NiFe2O4 NPs are 11.3 and 10.2 nm respectively for samples NiFe2O4-3 and NiFe2O4-4. A slight decrease in the particle size in sample NiFe2O4-4 might be attributed to the high hydrothermal aging time. Further, the average size obtained from TEM is slightly larger than the crystallite sizes of NiFe2O4 obtained from XRD results.

Fig. 3. TEM images of the as-prepared NiFe2O4 NPs: (a) TEM image, (b) HRTEM image, and (c) SAED pattern recorded from sample NiFe2O4-3 and (d) TEM image, (e) HRTEM image, and (f) SAED pattern recorded from sample NiFe2O4-4.

3.3. Magnetic property study

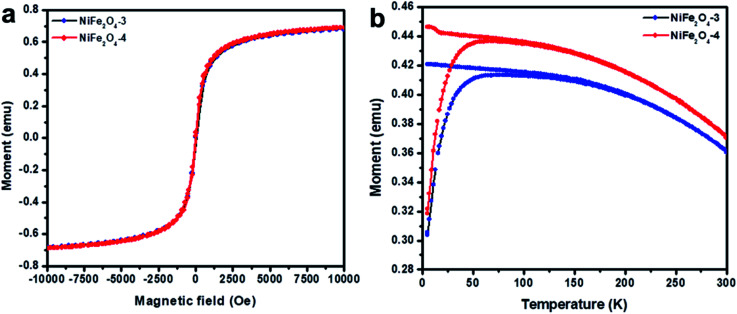

The hysteresis curve of the NiFe2O4 NPs was investigated using a vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM) at room temperature (300 K). The hysteresis curves of NiFe2O4 samples are shown in Fig. 4a. The NiFe2O4 NPs in both the samples exhibit super-paramagnetic behavior with the saturation magnetic moment (Ms) of 0.6 emu and without magnetic hysteresis loop, coercivity (Hc), and remanent magnetization (Mr). A similar observation was also noticed in the magnetic properties of NiFe2O4 NPs in sample NiFe2O4-4 which is a characteristic of super-paramagnetism.43 The obtained saturation magnetization (Ms) value is lower than the values of bulk NiFe2O4 particles reported elsewhere.11 Super-paramagnetic behavior arises from the fact that when a magnetic field is applied, the NPs need to overcome the thermal barrier to align themselves with the direction of the field and above TB due to thermal energy, this barrier is overcome.

Fig. 4. (a) Magnetic hysteresis curves (M vs. H) of samples NiFe2O4-3 and NiFe2O4-4 at 300 K and (b) temperature dependence of magnetization of samples NiFe2O4-3 and NiFe2O4-4 measured under field-cooled (FC) and zero-field-cooled (ZFC) conditions at an applied field of 500 Oe.

The temperature-dependent magnetization of NiFe2O4 NPs was studied from zero field cooling-field cooling (ZFC-FC) measurements. For the ZFC-FC measurements, the sample was cooled down to 5 K in zero fields and the magnetization was recorded as the sample was heated to 300 K in an applied field of 500 Oe. Then, the sample was cooled to 5 K under an applied field of 500 Oe and the magnetization was recorded as the sample was heated to 300 K in the same field. The ZFC-FC curves of NiFe2O4 NPs are shown in Fig. 4b that exhibited a sharp divergence below 150 K with blocking temperatures (TB) around 75 and 58 K respectively for samples NiFe2O4-3 and NiFe2O4-4. That is, the sample of NiFe2O4 NPs has a maximum in ZFC measurements and constant moments below TB for FC measurements. This was due to the blocking of magnetic moments because of the presence of anisotropy. Such divergence of the magnetization below the blocking temperature in the ZFC-FC measurements is due to the existence of the energy barriers of magnetic anisotropy and the slow relaxation of the particles below the blocking temperature. This magnetic anisotropy energy barrier is the key to superparamagnetic relaxation.

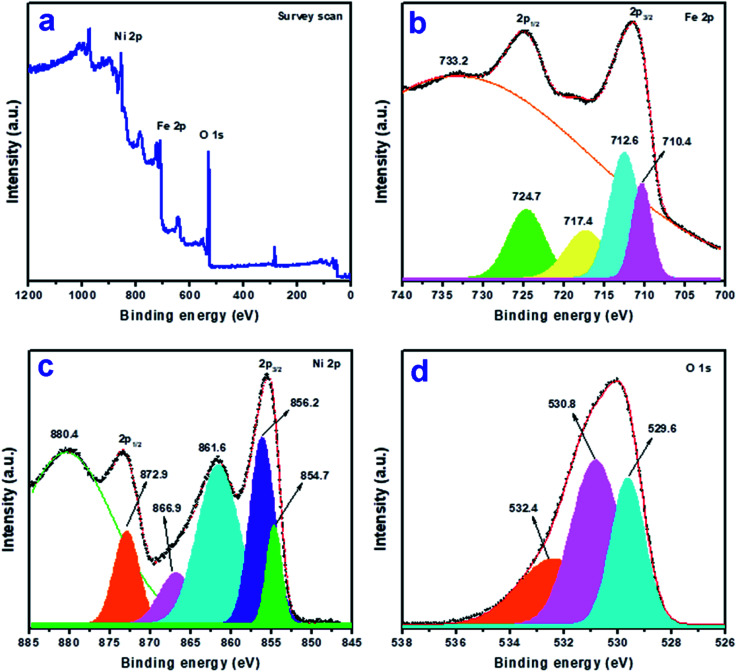

3.4. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy study

To study the elemental composition and the oxidation states of the elements present in the synthesized product, we analyzed the sample NiFe2O4-4 by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). A typical survey scan XPS spectrum present in Fig. 5a shows the presence of elements O 1s, Ni 2p, and Fe 2p. The high-resolution XPS spectrum of the core level Fe 2p region (Fig. 5b) shows two broad peaks at a binding energy of 724.9 eV (Fe 2p1/2) and 711.5 eV (Fe 2p3/2) with a satellite peak of Fe 2p3/2 at around ∼718.2 eV. These peaks correspond to the presence of Fe in the Fe(iii) state in the product.44 The presence of a satellite peak further supports the absence of the Fe3O4 phase in the composite. The Fe 2p3/2 peak can further be fitted into two peaks at ∼712.6 and ∼710.4 eV which corresponds to the presence of Fe3+ ions in both octahedral and tetrahedral sites of NiFe2O4 respectively.44 These observations further indicate that NiFe2O4 has a partial inverse spinel structure. Fig. 5c shows the high-resolution XPS spectrum of core level Ni 2p where two peaks were observed at 873.4 (Ni 2p1/2) and 855.5 (Ni 2p3/2) which are accompanied by another satellite peak at 861.6 eV. The Ni 2p3/2 peak can further be fitted into two peaks at ∼856.2 and ∼854.7 eV which reveals the presence of two non-equivalent bonds due to two types of lattice sites, i.e. tetrahedral and octahedral sites of NiFe2O4.44Fig. 5d shows the O 1s core-level spectrum, where three peaks were observed at 529.6, 530.8, and 532.4 eV in the fitted curve. The peak found at 529.6 eV is due to O2− in the NiFe2O4 crystal lattice, whereas the peak at 530.8 is due to the chemisorbed oxygen associated with the surface adsorbed hydroxyl groups. The peak at binding energy 532.4 eV is attributed to the presence of water. A similar observation was reported earlier for NiFe2O4 thin films deposited on a quartz substrate deposited by radiofrequency magnetron sputtering.45

Fig. 5. X-ray photoelectron spectra of sample NiFe2O4-4: (a) survey scan, and (b) Fe 2p, (c) Ni 2p, and (d) O 1s regions.

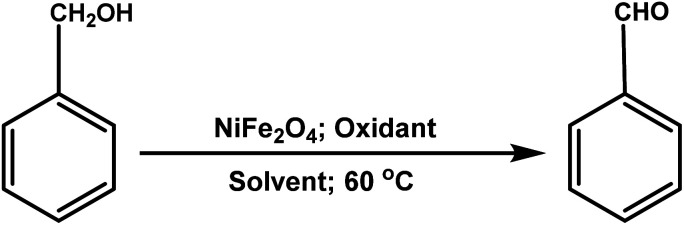

3.5. Oxidation of benzyl alcohol

To investigate the catalytic activity of prepared NiFe2O4 NPs, oxidation of benzyl alcohol was chosen. For the selection of oxidants, we tried first the oxidation of benzyl alcohol using different mild oxidants such as O2, H2O2, and TBHP in the absence of any solvent. The use of molecular O2 and H2O2 shows no significant conversion over a considerable time at 60 °C when 10 mg catalyst was used (Table 1; entry 1 and 2). The ineffectiveness of H2O2 in this system might be due to the possible decomposition of H2O2 over ferrite catalysts as reported earlier.46 We observed that the system offers satisfactory results with TBHP (Table 1; entry 3). So, TBHP was used as an oxidant for the catalytic oxidation of benzyl alcohol. We also tried to investigate whether the reaction can be performed without a catalyst which produced a trace amount of product that undergoes further oxidation to benzoic acid (Table 1; entry 4). This result revealed the usefulness of a catalyst for the oxidation of benzyl alcohol using TBHP as the oxidant at 60 °C. In the next assessment, the activity of the prepared catalyst was studied under different solvent atmospheres. So, we performed a set of reactions in the presence of different solvents such as ethanol, methanol, 2-propanol, acetonitrile, and water (Table 1, entry 5 to 9). Surprisingly in acetonitrile medium maximum activity of the catalyst was observed at 60 °C (Table 1, entry 8). The reaction achieved a conversion yield of 85% in 3 h. Polar and polar protic solvents like water and ethanol showed no satisfactory conversion (Table 1, entry 5, and 9), while methanol and 2-propanol offered a conversion of 15 and 42% yield respectively (Table 1, entry 6 and 7). So, we consider acetonitrile to be the effective solvent for the proposed conversion for the remaining study. The formation of the product was initially confirmed by the FTIR spectra (Fig. S3 in the ESI†). In the FTIR spectrum of pure benzyl alcohol, the broadband located at 3325.6 cm−1 could be attributed to the O–H stretching. The band shows peaks at 2878.2 cm−1 and 1452.9 cm−1 which are attributed to the C–H stretching and C–O–H peak respectively, whereas, in the spectrum of the product, an intense peak located at 1733.1 cm−1 could be observed which is attributed to the C O stretching of benzaldehyde. The peaks at 2850.2 and 2920.9 cm−1 are associated with C–H stretching of the aldehyde respectively. The band located at 2959.2 cm−1 is attributed to the C–H aromatic stretching of the aldehyde.

Optimization of reaction conditions for the oxidation of benzyl alcohol in terms of solvent and oxidanta.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Solvent (mL) | Oxidant (mL) | Time (h) | Yieldc (%) |

| 1 | — | O2 | 6 | Trace |

| 2 | — | H2O2 (0.5) | 6 | Trace |

| 3 | — | TBHP (0.05) | 6 | 30 |

| 4b | — | TBHP (0.05) | 6 | Trace |

| 5 | C2H5OH (3.0) | TBHP (0.05) | 6 | Trace |

| 6 | CH3OH (3.0) | TBHP (0.05) | 6 | 15 |

| 7 | 2-Propanol (3.0) | TBHP (0.05) | 6 | 42 |

| 8 | CH3CN (3.0) | TBHP (0.05) | 3 | 85 |

| 9 | H2O (3.0) | TBHP (0.05) | 6 | Trace |

Benzyl alcohol = 1.0 mmol; catalyst = 10 mg (0.04 mmol).

No catalyst was used.

Isolated yield.

To investigate the effect of temperature on the catalytic activity, we varied the temperature from room temperature to 110 °C (Table 2, entry 1–5). We observed that under similar reaction conditions the best yield of 87% was achieved at 110 °C in 3 h (Table 2, entry 1). However, the use of such a high temperature violates the rule of green chemistry and so the study is believed to be irrelevant. Optimizing and reducing the temperature to 60 °C with the same reaction condition showed a conversion with an 85% yield in 3 h (Table 2, entry 2). Further reduction of temperature to 50 and 40 °C slowed down the conversion and the calculated yield was found to be 73 and 55% respectively after 3 h (Table 2, entry 3, 4). When the reaction was carried out at room temperature (26 °C), nearly 20% conversion was observed after 24 h (Table 2, entry 5). So the best temperature was chosen as 60 °C for the remaining study. In the next step, we optimized the reaction for the catalyst loading (Table 2, entry 6–8) and observed that 5 mg (0.02 mmol) of the NiFe2O4 NP catalyst produces a conversion with a 60% yield under similar reaction conditions. When the catalyst loading was further increased to 10, 15, and 20 mg, conversion with 85% yield was obtained at 60 °C in 3 h (Table 2). So, for the next assessment, we fixed the catalyst loading at 10 mg (0.04 mmol). Further to find the minimum amount of oxidant required for satisfactory conversion, we varied the amount of oxidant from 0.01 mL (0.08 mmol) to 0.1 mL (0.8 mmol) (Table 2, entry 9–11). We observed that 0.05 mL (0.4 mmol) of TBHP is sufficient for the maximum conversion (Table 2, entry 2).

Optimization of temperature, catalyst loading, and oxidant amounta.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | NiFe2O4 (mg) | TBHP (mL) | Temperature (°C) | Time (h) | Yieldb (%) |

| 1 | 10 | 0.05 | 110 | 3 | 87 |

| 2 | 10 | 0.05 | 60 | 3 | 85 |

| 3 | 10 | 0.05 | 50 | 3 | 73 |

| 4 | 10 | 0.05 | 40 | 3 | 55 |

| 5 | 10 | 0.05 | rt | 24 | ∼20 |

| 6 | 5 | 0.05 | 60 | 3 | 60 |

| 7 | 15 | 0.05 | 60 | 3 | 85 |

| 8 | 20 | 0.05 | 60 | 3 | 85 |

| 9 | 10 | 0.01 | 60 | 3 | 52 |

| 10 | 10 | 0.03 | 60 | 3 | 70 |

| 11 | 10 | 0.1 | 60 | 3 | 60 |

Reaction conditions: benzyl alcohol: 1 mmol.

Isolated yield.

It is well known that t-BuOOH mediated reactions proceed via a free radical mechanism. To prove the fact, we carried out a reaction in the presence of a radical quencher, hydroquinone which is an effective free radical scavenger for TBHP as reported earlier.47 So, a set of reactions in the presence of hydroquinone (0.5 mmol) were performed keeping all other reaction parameters fixed as the parent reaction. As expected, we observed that the reaction is inhibited in the presence of the radical quencher as no significant product formation was noticed after 3 h of reaction. This observation proved that the reaction proceeds through the involvement of the radical intermediate. Further, to examine the efficiency and capability of the present protocol, the result of the current study is compared with other related ferrite and non-ferrite based catalyst systems (Table 3). The comparative study revealed the effectiveness of the current catalyst system in the selective oxidation of benzyl alcohol to benzaldehyde under mild reaction conditions. Also, it can be seen that most of the catalysts required support which played a major role in the enhanced activity of the catalyst. However, the present catalyst system attained almost similar activity without any support materials.

Comparison of the efficiency of the current catalyst in the oxidation of benzyl alcohol to benzaldehyde with a few reported ferrite and non-ferrite catalysts.

| Entry | Catalyst (Amount) | Oxidant | Temperature (°C) | Solvent | Time (h) | Conversion (%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CoFe2O4 NPs | H2O2 | 110 | — | 5 h | >99 | 40 |

| 2 | Supported NiFe2O4 | O2 | 80 | Acetonitrile | — | 77 | 36 |

| 3 | NiFe2O4 | TBHP | 120 (MW) | — | 2 h | 46.2 | 48 |

| 4 | CoFe2O4 | TBHP | 120 (MW) | — | 2 h | 88.9 | 48 |

| 5 | Nano CoFe2O4 | Oxone | rt | Water | 20 min | 93 | 37 |

| 6 | CuFe2O4 | O2/TEMPO | 100 | Water | 24 h | 95 | 38 |

| 7 | CoFe2O4@SiO2 | H2O2 | rt | Water | 6 h | 51.2 | 49 |

| 8 | Nano-functionalized NiFe2O4 | H2O2 | 80 | Acetonitrile | 7 h | 82.4 | 39 |

| 9 | PEG-NiFe2O4 NPs | H5IO6 | rt | Water | 1.5 h | 98 | 16 |

| 10 | ZrOx-MnCO3/HRG nanocomposites | O2 | 100 | Toluene | 4 min | ∼99 | 29 |

| 11 | La0.95Ce0.05MnO3 | O2 | 120 | Toluene | 12 h | 40 | 32 |

| 12 | Au/Sm-CeO2 | O2 | 90 | Toluene | 3 h | 27.4 | 21 |

| 13 | Polyoxometalate-based catalyst PW4/DAIL/MIL-100(Fe) | TBHP | 100 | Chloroform | 6 h | 92 | 33 |

| 14 | MnO2 NPs (calcined) | TBHP | 110 | Alcohol | 24 h | 89 | 34 |

| 15 | Ce0.8Zr0.2O2 | TBHP | 120 | — | 4 h | 92.5 | 50 |

| 16 | NiFe2O4 NPs | TBHP | 60 | Acetonitrile | 3 h | 85 | This work |

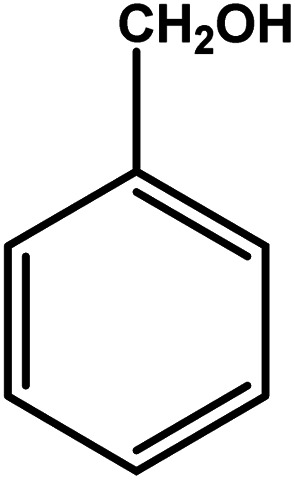

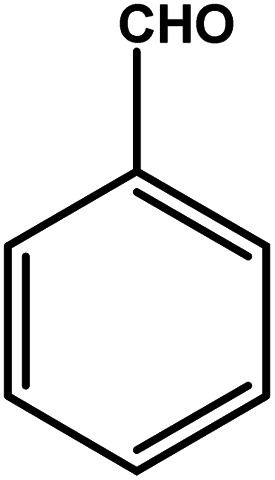

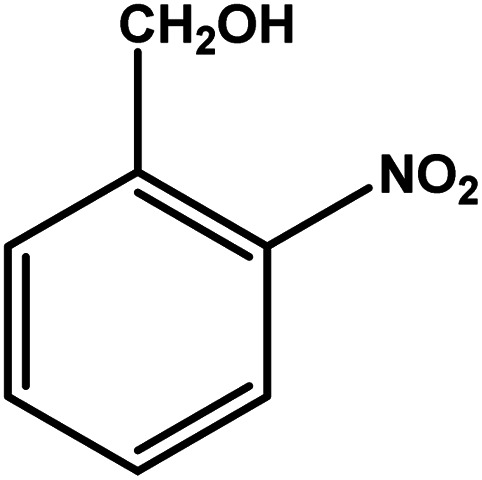

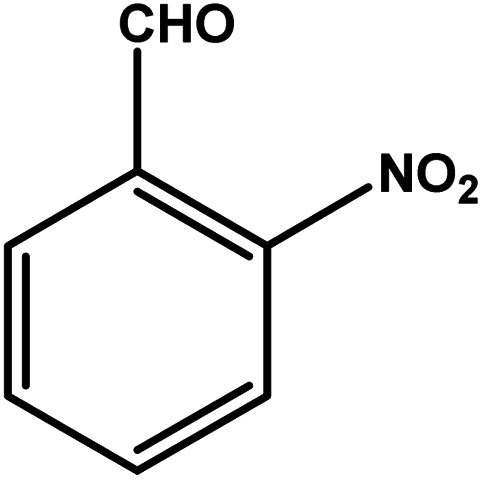

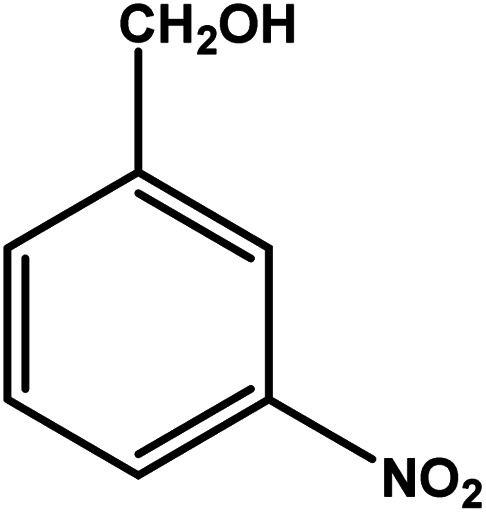

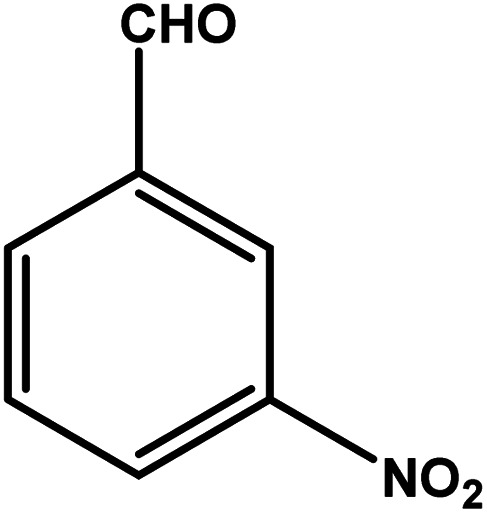

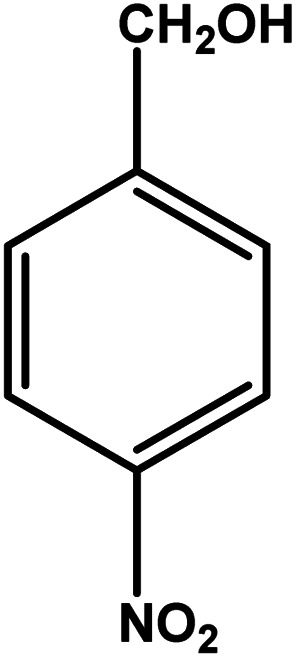

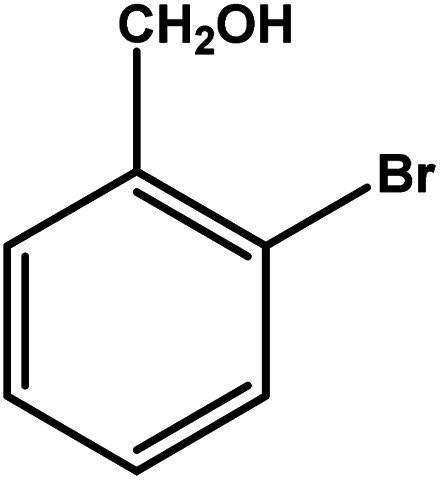

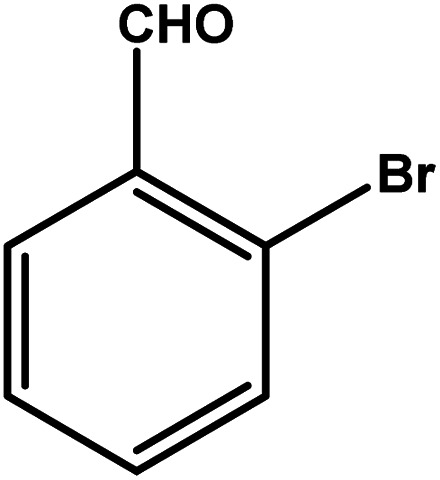

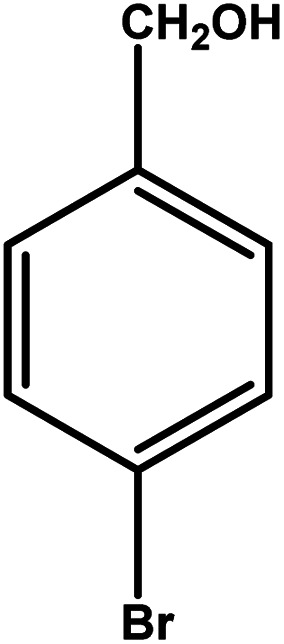

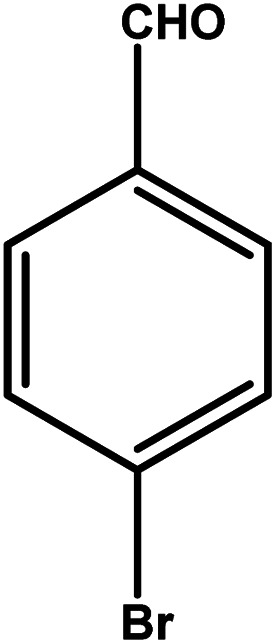

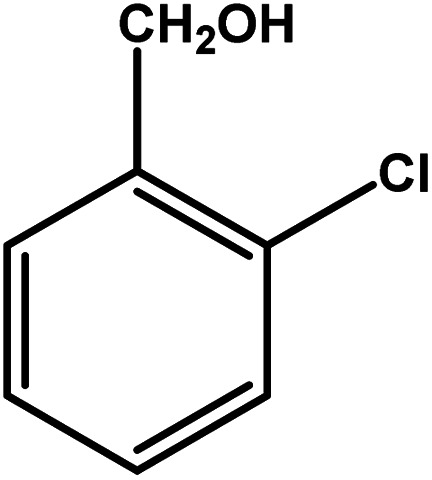

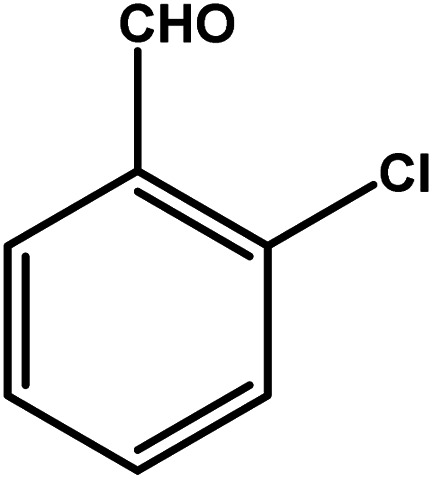

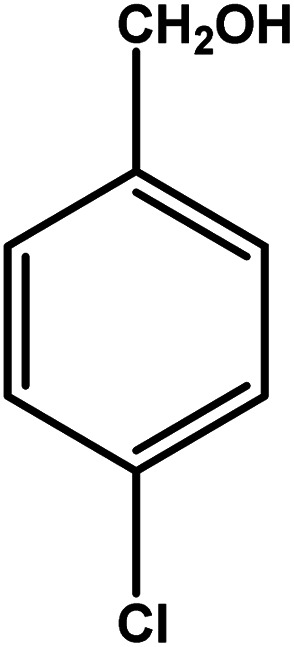

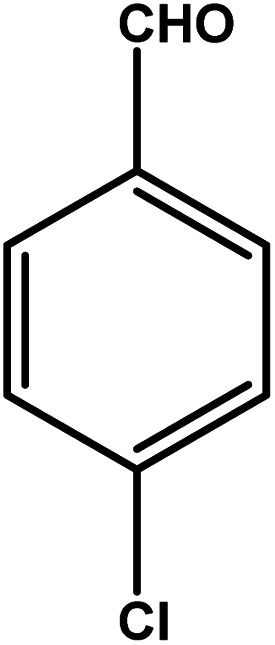

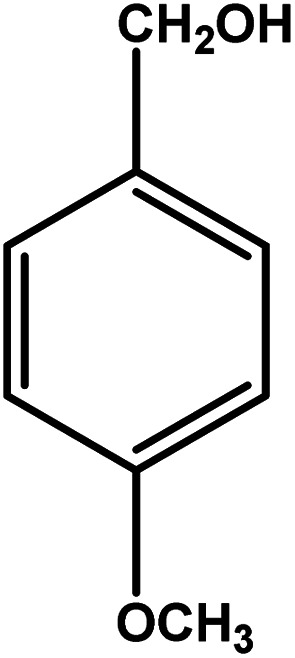

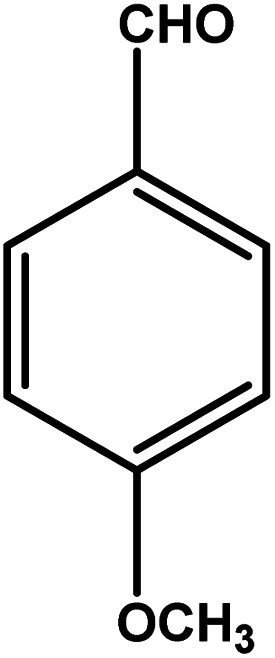

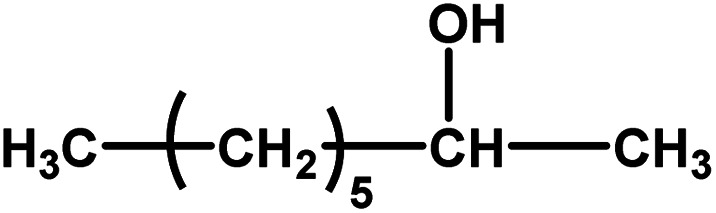

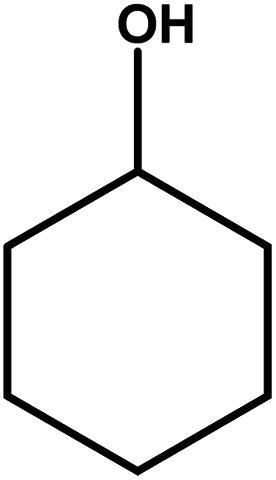

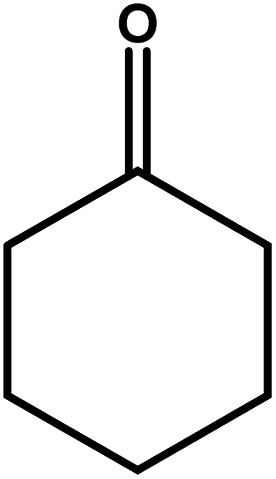

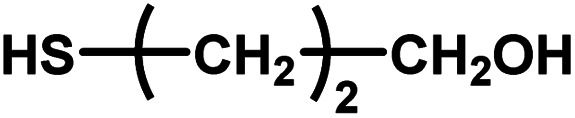

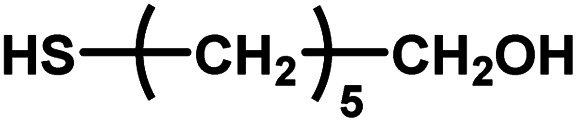

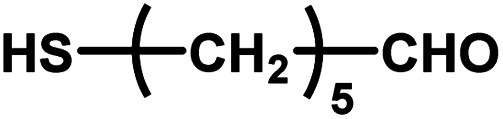

To find the general applicability and the effectiveness of the TBHP/NiFe2O4 catalytic system, oxidations of various substituted benzyl alcohols and a few aliphatic and heteroatomic alcohols were performed under the optimized conditions and the results are shown in Table 4. It can be seen from Table 4 that the p-substituted electron-withdrawing group (–NO2, –Cl, and –Br) showed a greater yield of the product, whereas the ortho and meta substituted benzyl alcohols produce a lower yield. This might be due to the hindrance effect at the ortho position which causes slow oxidation of alcohol. On the other hand, the electron-donating group (–OCH3) at the p-position of the ring also showed a low product formation in comparison with the electron-withdrawing group but a slightly better yield compared to the ortho and para-substituted electron-withdrawing groups. The specific catalytic activity, turnover number (TON), and turnover frequency (TOF) was found to be high for p-bromo benzyl alcohol. It was also observed that the current optimized conditions are too mild for the oxidation of aliphatic as well as heteroatomic alcohols (Table 4; entry 10–13) as a trace amount or no product formation was observed with these alcohols. The absence of conjugation in the β-position of the hydroxyl group might be the reason for this observation as reported earlier.29 Also, the literature reports suggest that the oxidation of aliphatic alcohols is much more difficult than the oxidation of aromatic alcohols.30,31,51,52 From these results, we conclude that the experimental conditions of the present catalyst system are not so favourable for the oxidation of aliphatic alcohols but very effective for selective oxidation of benzylic alcohols.

Catalytic performance in the oxidation of benzylic and aliphatic alcoholsa.

| Entry | Alcohol | Product | Time (h) | Conversionb (%) | Specific activity (mmol g−1 h−1) | TONc | TOFd (h−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

|

3 | 85 | 28.3 | 21.25 | 7.1 |

| 2 |

|

|

3 | 76 | 25.3 | 19.0 | 6.3 |

| 3 |

|

|

3 | 70 | 23.3 | 17.5 | 5.8 |

| 4 |

|

|

3 | 88 | 29.3 | 22.0 | 7.3 |

| 5 |

|

|

3.5 | 75 | 21.4 | 18.75 | 5.3 |

| 6 |

|

|

2 | 88 | 44.0 | 22.0 | 11.0 |

| 7 |

|

|

4 | 68 | 17.0 | 17.0 | 4.3 |

| 8 |

|

|

3 | 81 | 27.0 | 20.25 | 6.8 |

| 9 |

|

|

3 | 79 | 26.3 | 19.75 | 6.6 |

| 10 |

|

No reaction | 24 (observation) | — | — | — | — |

| 11 |

|

|

18–24 | Trace amount | — | — | — |

| 12 |

|

No reaction | 24 (observation) | — | — | — | — |

| 13 |

|

|

12–24 | ∼30 | — | — | — |

Reaction conditions: benzyl alcohol: 1 mmol; TBHP: 0.5 mmol; NiFe2O4: 10 mg; solvent: CH3CN; temperature: 60 °C.

Isolated yield.

TON: turnover number = number of moles of substrate consumed/number of moles of catalyst.

TOF: turnover frequency = TON/time of reaction in h.

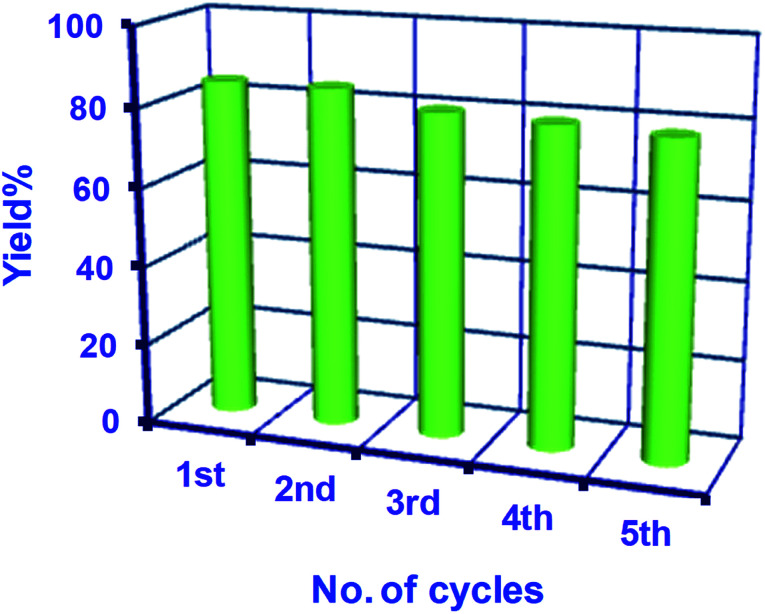

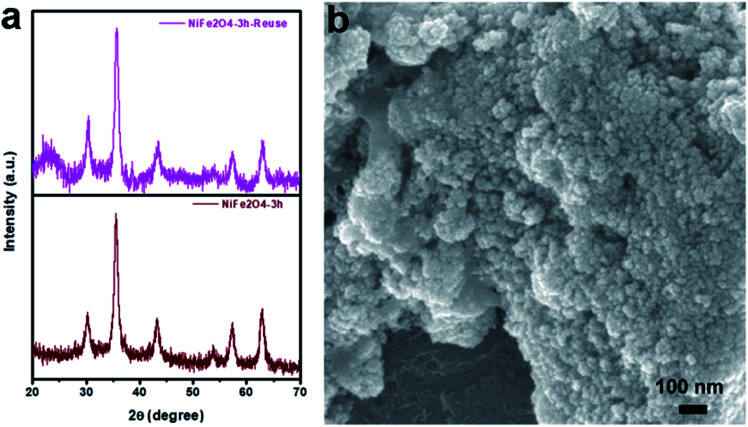

To check the reusability of the catalyst, first, we separated the catalyst magnetically using a bar magnet after the reaction, and the isolated products were purified by washing with water and a water–ethanol mixture to get rid of any organic reactants or products. The isolated mass was dried in an oven at 60 °C under vacuum overnight. The isolated catalyst was used for new batches of the oxidation reaction under identical reaction conditions as discussed above. The process of isolation, purification, and the catalysis reaction were repeated for 5 cycles. The performance of the reused catalyst was quite satisfactory up to the 5th cycle (Fig. 6). To study the fate of NiFe2O4 NPs during catalysis, the solid catalyst was isolated after the first cycle of reaction and dried at 60 °C under vacuum for further characterization. The XRD pattern of the used NiFe2O4 NPs exhibited similar crystalline properties with the nascent NiFe2O4 NPs (Fig. 7a). No major change in the crystalline properties was observed due to catalysis, although background noise could be observed in the XRD pattern. This might be due to the low quantity of the recovered sample. Also, the SEM image of the recovered sample (Fig. 7b) shows the presence of uniformly distributed spherical NiFe2O4 NPs. The results confirmed the stability of the sample during the catalysis.

Fig. 6. Bar diagram showing the yield% of the product in different cycles of reuse of NiFe2O4 NPs.

Fig. 7. (a) XRD pattern and (b) SEM image of the recovered NiFe2O4 NPs after catalysis.

4. Conclusion

Spherical NiFe2O4 NPs of sizes below 12 nm have been prepared by a precipitation method coupled with hydrothermal aging in water. The formed NiFe2O4 NPs are pure and highly crystalline possessing cubic structures. The hydrothermal aging time does not have any influence on the particle size and morphology. The NiFe2O4 NPs exhibit super-paramagnetic behavior with the saturation magnetic moment (Ms) of 0.6 emu without any magnetic hysteresis loop, coercivity (Hc), and remnant magnetization (Mr). These ferrite NPs exhibit excellent catalytic activity in the selective oxidation of benzyl alcohol and substituted benzyl alcohol under ambient conditions with 100% selectivity. Being magnetic, these ferrite NPs are easily separable from the reaction mixture with a simple bar magnet and are reusable up to five cycles without loss of catalytic activity.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

SI acknowledges Rajiv Gandhi University for providing the research fellowship. The authors also thank IACS Kolkata, NEIST Jorhat, SAIC, TU, UGC-DAE CSR Indore (Dr A. Banerjee, and Dr M. Gupta) and UGC-DAE CSR Kalpakkam (Dr S. Hussain) for providing instrumental facilities to us.

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/d0na00591f

References

- Sugimoto M. The past, present, and future of ferrites. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1999;82:269–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1551-2916.1999.tb20058.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta N. Jain P. Rana R. Shrivastava S. Current development in synthesis and characterization of nickel ferrite nanoparticle. Mater. Today: Proc. 2017;4:342–349. [Google Scholar]

- Šutka A. Pärna R. Käämbre T. Kisand V. Synthesis of p-type and n-type nickel ferrites and associated electrical properties. Phys. B. 2015;456:232–236. doi: 10.1016/j.physb.2014.09.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava M. Chaubey S. Ojha A. K. Investigation on size dependent structural and magnetic behavior of nickel ferrite nanoparticles prepared by sol–gel and hydrothermal methods. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2009;118:174–180. doi: 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2009.07.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lasheras X. Insausti M. Gil de Muro I. Garaio E. Plazaola F. Moros M. De Matteis L. de la Fuente J. M. Lezama L. Chemical synthesis and magnetic properties of monodisperse nickel ferrite nanoparticles for biomedical applications. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2016;120:3492–3500. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b10216. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharifi I. Shokrollahi H. Amiri S. Ferrite-based magnetic nanofluids used in hyperthermia applications. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2012;324:903–915. doi: 10.1016/j.jmmm.2011.10.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Umut E. Coşkun M. Pineider F. Berti D. Güngüneş H. Nickel ferrite nanoparticles for simultaneous use in magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic fluid hyperthermia. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019;550:199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2019.04.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Dief A. M. Nassar I. F. Elsayed W. H. Magnetic NiFe2O4 nanoparticles: Efficient, heterogeneous and reusable catalyst for synthesis of acetylferrocene chalcones and their anti-tumour activity. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2016;30:917–923. doi: 10.1002/aoc.3521. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atashkar B. Rostami A. Rostami A. Zolfigol M. A. NiFe2O4 as a magnetically recoverable nanocatalyst for odourless C-S bond formation via the cleavage of C–O bond in the presence of S8 under mild and green conditions. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2019;33:e4691. doi: 10.1002/aoc.4691. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bućko M. M. Haberko K. Hydrothermal synthesis of nickel ferrite powders, their properties and sintering. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2007;27:723–727. doi: 10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2006.04.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. Shi J. Gong M. Synthesis of magnetic nickel spinel ferrite nanospheres by a reverse emulsion-assisted hydrothermal process. J. Solid State Chem. 2009;182:2135–2140. doi: 10.1016/j.jssc.2009.05.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huo J. Wei M. Characterization and magnetic properties of nanocrystalline nickel ferrite synthesized by hydrothermal method. Mater. Lett. 2009;63:1183–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2009.02.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W. Zhang L. Zhao B. Du Y. Zhou X. Growth mechanism of octahedral like nickel ferrite crystals prepared by modified hydrothermal method and morphology dependent magnetic performance. Ceram. Int. 2018;44:9809–9815. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2018.02.219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kesavan G. Nataraj N. Chen S.-M. Lin L.-H. Hydrothermal synthesis of NiFe2O4 nanoparticles as an efficient electrocatalyst for the electrochemical detection of bisphenol A. New J. Chem. 2020;44:7698–7707. doi: 10.1039/D0NJ00608D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Safaei M. Beitollahi H. Shishehbore M. R. Synthesis and characterization of NiFe2O4 nanoparticles using the hydrothermal method as magnetic catalysts for electrochemical detection of norepinephrine in the presence of folic acid. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2019;66:1597–1603. doi: 10.1002/jccs.201900073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paul B. Purkayastha D. D. Dhar S. S. Size-controlled synthesis of NiFe2O4 nanospheres via a PEG assisted hydrothermal route and their catalytic properties in oxidation of alcohols by periodic acid. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016;370:469–475. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.02.129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karaagac O. Atmaca S. Kockar H. A facile method to synthesize nickel ferrite nanoparticles: Parameter effect. J. Supercond. Novel Magn. 2017;30:2359–2369. doi: 10.1007/s10948-016-3796-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. Wu H.-z. Xiao G.-x. Effects of synthetic conditions on particle size and magnetic properties of NiFe2O4. Powder Technol. 2010;198:157–166. doi: 10.1016/j.powtec.2009.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rafique M. Y. Ellahi M. Iqbal M. Z. Javed Q.-u.-a. Pan L. Gram scale synthesis of single crystalline nano-octahedron of NiFe2O4: Magnetic and optical properties. Mater. Lett. 2016;162:269–272. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2015.10.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nejati K. Zabihi R. Preparation and magnetic properties of nano size nickel ferrite particles using hydrothermal method. Chem. Cent. J. 2012;6:23. doi: 10.1186/1752-153X-6-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal S. Bando K. K. Santra C. Maity S. James O. O. Mehta D. Chowdhury B. Sm-CeO2 supported gold nanoparticle catalyst for benzyl alcohol oxidation using molecular O2. Appl. Catal., A. 2013;452:94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.apcata.2012.11.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kahlich D., Wiechern U. and Lindner J., Propylene oxide; ullmann's encyclopedia of industrial chemistry, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co., 2000 [Google Scholar]

- Patel A. Pathan S. Solvent free selective oxidation of styrene and benzyl alcohol to benzaldehyde over an eco-friendly and reusable catalyst, undecamolybdophosphate supported onto neutral alumina. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012;51:732–740. doi: 10.1021/ie2020608. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan G. Hong Y. Lu F. Ibrahim A.-R. Du M. Sun D. Huang J. Li Q. Li J. Kinetics of liquid phase oxidation of benzyl alcohol with hydrogen peroxide over bio-reduced Tu/TS-1 catalysts. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2013;366:215–221. doi: 10.1016/j.molcata.2012.09.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wiener C. and Pittet Alan O., Process for preparing natural benzaldehyde and acetaldehyde, natural benzaldehyde and acetaldehyde compositions, products produced thereby and organoleptic utilities therefor, US Pat. US 4617419 A, 1986

- Kantham M., Shreekanth P., Rao K., Kumar T., Rao B. C., and Choudhury B., Selective liquid phase air oxidation of toluene catalysed by composite catalytic system, Patent Appl. US6743952B2, 2003

- Chai J. Chong H. Wang S. Yang S. Wu M. Zhu M. Controlling the selectivity of catalytic oxidation of styrene over nanocluster catalysts. RSC Adv. 2016;6:111399–111405. doi: 10.1039/C6RA23014H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kopylovich M. N., Ribeiro A. P. C., Alegria E. C. B. A., Martins N. M. R., Martins L. M. D. R. S. and Pombeiro A. J. L., in Advances in organometallic chemistry, ed. P. J. Pérez, Academic Press, 2015, vol. 63, pp. 91–174 [Google Scholar]

- Assal M. E. Shaik M. R. Kuniyil M. Khan M. Al-Warthan A. Siddiqui M. R. H. Khan S. M. A. Tremel W. Tahir M. N. Adil S. F. A highly reduced graphene oxide/ZrOx–MnCO3 or –Mn2O3 nanocomposite as an efficient catalyst for selective aerial oxidation of benzylic alcohols. RSC Adv. 2017;7:55336–55349. doi: 10.1039/C7RA11569E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Assal M. E. Shaik M. R. Kuniyil M. Khan M. Alzahrani A. Y. Al-Warthan A. Siddiqui M. R. H. Adil S. F. Mixed zinc/manganese on highly reduced graphene oxide: A highly active nanocomposite catalyst for aerial oxidation of benzylic alcohols. Catalysts. 2017;7:391. doi: 10.3390/catal7120391. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Assal M. E. Kuniyil M. Shaik M. R. Khan M. Al-Warthan A. Siddiqui M. R. H. Adil S. F. Synthesis, characterization, and relative study on the catalytic activity of zinc oxide nanoparticles doped MnCO3, –MnO2, and –Mn2O3 nanocomposites for aerial oxidation of alcohols. J. Chem. 2017;2017:2937108. doi: 10.1155/2017/2937108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ansari A. A. Ahmad N. Alam M. Adil S. F. Ramay S. M. Albadri A. Ahmad A. Al-Enizi A. M. Alrayes B. F. Assal M. E. Alwarthan A. A. Physico-chemical properties and catalytic activity of the sol-gel prepared Ce-ion doped LaMnO3 perovskites. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:7747. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-44118-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abednatanzi S. Abbasi A. Masteri-Farahani M. Immobilization of catalytically active polyoxotungstate into ionic liquid-modified MIL-100(Fe): A recyclable catalyst for selective oxidation of benzyl alcohol. Catal. Commun. 2017;96:6–10. doi: 10.1016/j.catcom.2017.03.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar F. Nunes C. D. Selective catalytic oxidation of benzyl alcohol by MoO2 nanoparticles. Catalysts. 2020;10:265. doi: 10.3390/catal10020265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gawande M. B. Rathi A. Nogueira I. D. Ghumman C. A. A. Bundaleski N. Teodoro O. M. N. D. Branco P. S. A recyclable ferrite–Co magnetic nanocatalyst for the oxidation of alcohols to carbonyl compounds. ChemPlusChem. 2012;77:865–871. doi: 10.1002/cplu.201200081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saranya R. Raj R. A. AlSalhi M. S. Devanesan S. Dependence of catalytic activity of nanocrystalline nickel ferrite on its structural, morphological, optical, and magnetic properties in aerobic oxidation of benzyl alcohol. J. Supercond. Novel Magn. 2018;31:1219–1225. doi: 10.1007/s10948-017-4305-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sadri F. Ramazani A. Massoudi A. Khoobi M. Azizkhani V. Tarasi R. Dolatyari L. Min B.-K. Magnetic CoFe2O4 nanoparticles as an efficient catalyst for the oxidation of alcohols to carbonyl compounds in the presence of oxone as an oxidant. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2014;35:2029–2032. doi: 10.5012/bkcs.2014.35.7.2029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X. Yang D. Wei W. Jiang M. Li L. Zhu X. You J. Wang H. Magnetic copper ferrite nanoparticles/TEMPO catalyzed selective oxidation of activated alcohols to aldehydes under ligand- and base-free conditions in water. RSC Adv. 2014;4:64930–64935. doi: 10.1039/C4RA14152K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat P. B. Bhat B. R. Magnetically retrievable nickel hydroxide functionalised AFe2O4 (A = Mn, Ni) spinel nanocatalyst for alcohol oxidation. Appl. Nanosci. 2016;6:425–435. doi: 10.1007/s13204-015-0456-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nasrollahzadeh M. Bagherzadeh M. Karimi H. Preparation, characterization and catalytic activity of CoFe2O4 nanoparticles as a magnetically recoverable catalyst for selective oxidation of benzyl alcohol to benzaldehyde and reduction of organic dyes. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016;465:271–278. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2015.11.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivakumar P. Ramesh R. Ramanand A. Ponnusamy S. Muthamizhchelvan C. Preparation and properties of nickel ferrite (NiFe2O4) nanoparticles via sol–gel auto-combustion method. Mater. Res. Bull. 2011;46:2204–2207. doi: 10.1016/j.materresbull.2011.09.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesh K. Nandini N. Chen S.-M. Lin L.-H. Hydrothermal synthesis of NiFe2O4 nanoparticles as an efficient electrocatalyst for the electrochemical detection of bisphenol a. New J. Chem. 2020;44:7698–7707. doi: 10.1039/D0NJ00608D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deb P. Basumallick A. Chatterjee P. Sengupta S. P. Preparation of α-Fe2O3 nanoparticles from a nonaqueous precursor medium. Scr. Mater. 2001;45:341–346. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6462(01)01039-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav R. S. Havlica J. Masilko J. Kalina L. Wasserbauer J. Hajdúchová M. Enev V. Kuřitka I. Kožáková Z. Effects of annealing temperature variation on the evolution of structural and magnetic properties of NiFe2O4 nanoparticles synthesized by starch-assisted sol–gel auto-combustion method. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2015;394:439–447. doi: 10.1016/j.jmmm.2015.07.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Solís C. Somacescu S. Palafox E. Balaguer M. Serra J. M. Particular transport properties of NiFe2O4 thin films at high temperatures. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2014;118:24266–24273. doi: 10.1021/jp506938k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lahiri P. Sengupta S. K. Spinel ferrites as catalysts: A study on catalytic effect of coprecipitated ferrites on hydrogen peroxide decomposition. Can. J. Chem. 1991;69:33–36. doi: 10.1139/v91-006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waffel D. Alkan B. Fu Q. Chen Y.-T. Schmidt S. Schulz C. Wiggers H. Muhler M. Peng B. Towards mechanistic understanding of liquid-phase cinnamyl alcohol oxidation with tert-butyl hydroperoxide over noble-metal-free LaCo1–xFexO3 perovskites. ChemPlusChem. 2019;84:1155–1163. doi: 10.1002/cplu.201900429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins N. M. R. Martins L. M. D. R. S. Amorim C. O. Amaral V. S. Pombeiro A. J. L. Solvent-free microwave-induced oxidation of alcohols catalyzed by ferrite magnetic nanoparticles. Catalysts. 2017;7:222. doi: 10.3390/catal7070222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tan J. Liu X. B. Chen W. F. Hu Y. L. Synthesis of magnetically separable nanocatalyst CoFe2O4@SiO2@MIL-53(Fe) for highly efficient and selective oxidation of alcohols and benzylic compounds with hydrogen peroxide. ChemistrySelect. 2019;4:8477–8481. doi: 10.1002/slct.201901690. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akinnawo C. A. Bingwa N. Meijboom R. Tailoring the surface properties of meso-CeO2 for selective oxidation of benzyl alcohol. Catal. Commun. 2020;145:106115. doi: 10.1016/j.catcom.2020.106115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Assady E. Yadollahi B. Riahi Farsani M. Moghadam M. Zinc polyoxometalate on activated carbon: An efficient catalyst for selective oxidation of alcohols with hydrogen peroxide. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2015;29:561–565. doi: 10.1002/aoc.3332. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hasannia S. Yadollahi B. Zn–Al LDH nanostructures pillared by Fe substituted keggin type polyoxometalate: Synthesis, characterization and catalytic effect in green oxidation of alcohols. Polyhedron. 2015;99:260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.poly.2015.08.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.