Abstract

Insulin secretion is regulated in multiple steps, and one of the main steps is in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Here, we show that UDP-glucose induces proinsulin ubiquitination by cereblon, and uridine binds and competes for proinsulin degradation and behaves as sustainable insulin secretagogue. Using insulin mutagenesis of neonatal diabetes variant-C43G and maturity-onset diabetes of the young 10 (MODY10) variant-R46Q, UDP-glucose:glycoprotein glucosyltransferase 1 (UGGT1) protects cereblon-dependent proinsulin ubiquitination in the ER. Cereblon is a ligand-inducible E3 ubiquitin ligase, and we found that UDP-glucose is the first identified endogenous proinsulin protein degrader. Uridine-containing compounds, such as uridine, UMP, UTP, and UDP-galactose, inhibit cereblon-dependent proinsulin degradation and stimulate insulin secretion from 3 to 24 h after administration in β-cell lines as well as mice. This late and long-term insulin secretion stimulation is designated a day sustainable insulin secretion stimulation. Uridine-containing compounds are designated as proinsulin degradation regulators.

Subject terms: Bioinorganic chemistry, Carbohydrates, Chemical modification, Proteolysis, Endocrinology

Introduction

Impairment of insulin secretion leads to diabetes mellitus1–4. Hypoinsulinemia in insulin variants is found in maturity-onset diabetes of the young type 10 (MODY 10) and neonatal diabetes6–13. Mechanistically, insulin variants in MODY10 are considered to cause diabetes due to impaired processing of insulin leading to hypoinsulinemia proinsulinR46Q variant13 or impaired insulin receptor signaling in case of R89H-variant14. More severe hypoinsulinemia of the insulin variant of C43G15 is neonatal diabetes. The difference in MODY10 and neonatal diabetes is not yet known. Here, we found two different reasons for genetic hypoinsulinemia. One is that proinsulinR46Q is retained in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and not secreted. The other is that proinsulinC43G is ubiquitinated and degraded and then not secreted.

Insulin is secreted by stress response. One of the unfolding protein responses (UPRs) is ER-associated protein degradation (ERAD). Under (oxidative) stress, unfolding protein is eliminated by HMG-CoA reductase degradation 1 (HRD1) in the ER16–18. Another candidate ubiquitin ligase in the ER is cereblon19. Cullin–RING ubiquitin ligase complex 4 (CRL4) includes cullin4 (CUL4), DNA damage-binding protein 1 (DDB1) and cereblon (CRL4CRBN)20,21.

Here, we found that even the proinsulinWT protein was also degraded by the ERAD system, indicating that inhibiting proinsulin degradation leads to insulin secretion stimulation. Insulin secretagogues, such as glucose and arginine, stimulate insulin secretion immediately and are soon reduced22,23. It forms one sharp peak22,23. Here, using inhibition of the proinsulin ERAD system, we found several chemicals that induce daily sustainable insulin secretion.

Results

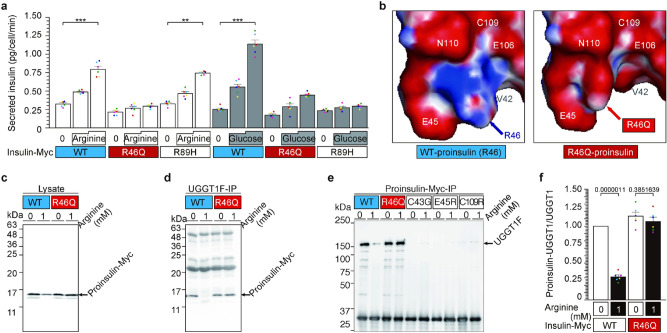

The R46 residue of proinsulin is involved in arginine-induced insulin secretion (Figs. 1 and S1)

Figure 1.

The R46 residue of proinsulin is involved in arginine-induced insulin secretion. (a) The R46 residue of proinsulin is involved in arginine-induced insulin secretion. NIT1 cells transfected with insulin-Myc vectors expressing WT, R46Q, and R89H were preincubated with arginine- or glucose-free F-12 K medium for 30 min. Then, the cells were treated with arginine or glucose for 5 min. The culture supernatant was collected, and secreted insulin was analyzed by ELISA. Data are presented as mean ± S.E. n = 6 **p < 0.005; ***p < 0.0001. (b) The predicted structure of R46 (WT) and R46Q proinsulin. Protruding R46 residue and surrounding amino acid ring of proinsulin. Basic groups are shown in blue, and acidic groups are shown in red. The original structural data of proinsulin (https://www.rcsb.org/structure/3w7y) were used 28. The non-protruding R46Q residue was calculated using PyMOL software. Other directions of the R46 and R46Q structures are shown in Fig. S1a. (c, and d) R46Q-mutated proinsulin protein bound to UGGT1 and was retained in the ER with/without arginine. NIT1 cells transfected with WT or R46Q proinsulin were pretreated in arginine-free F-12 k for 30 min and stimulated with 1 mM arginine for 5 min. Intracellular proinsulin and UGGT1 were analyzed by WB (c and Fig. S1b). Proinsulin bound to UGGT1 was assessed by IP of UGGT1 followed by IP-WB (d and Fig. S1c). (e, and f) Three proinsulin variants of the acid ring consisting of V42, C43, E45, E106, C109 and N110 residues of proinsulin were tested for their interaction with UGGT1 along with R46Q proinsulin. Vectors expressing mutated proinsulin were transfected, and cell lysates were prepared with or without arginine treatment. Proinsulin was immunoprecipitated and blotted for UGGT1 (c, d, Fig. S1b–d).

We previously reported that proinsulin increases its binding to UGGT1 and is retained in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) when β-cell lines and mouse pancreases are maintained under arginine-depleted conditions22. Arginine administration releases proinsulin from UGGT1 in the ER and causes new complex formation between arginine and UGGT1. To assess the physiological importance of this interaction, we performed mutagenesis of the proinsulin gene to express the proinsulin variant associated with MODY 10 (maturity-onset diabetes of the young). Among four arginine residues (R46, R55, R56 and R89) in proinsulin, three variants (R46Q, R55C, R89H) are reported to cause MODY104–9,13,14,24–26. R55, R56 and R89 are cleavage sites of protein convertase (PC1 and 2)4,10,11,13,14,27, and R46 is only one arginine residue of a non-cleavage site. Therefore, we chose two MODY 10 variants of proinsulin, R46Q and R89H, and tested the impact of the mutations on glucose- or arginine-induced secretion in NIT1 cells (Fig. 1a). Both arginine and glucose strongly induced WT insulin secretion, as expected. Glucose failed to induce secretion of MODY10 variants of R46Q and R89H insulin (Fig. 1a). Interestingly, arginine administration significantly induced R89H-insulin secretion but not R46Q-insulin secretion (Fig. 1a), indicating that the R46 residue is involved in arginine-induced insulin secretion.

The PDB database (https://www.rcsb.org/structure/3w7y)28 of proinsulin predicts that R46 is surrounded by a ring structure formed by valine 42 (V42), cysteine 43 (C43), glutamate 45 (E45), E106, C109, and asparagine 110 (N110) and protrudes from the plane formed by the ring (Figs. 1b and S1a). When a change in the three-dimensional structure of R46Q proinsulin was predicted using PyMOL software, the R46Q residue did not protrude from the ring (Figs. 1b and S1a). Immunoprecipitation of UGGT1 showed that the WT but not the R46 proinsulin residue interacts with UGGT1 in an arginine-dependent manner (Figs. 1c–e and S1b–d). We tested three insulin variants of C43G-neonatal diabetes, E45R and C109R, involving amino acids forming the ring structure, V42, C43, E45, E106, C109(-C43) and N110. C43G and C109R are associated with neonatal diabetes11,14,27. In agreement with immunoprecipitation of UGGT1, immunoprecipitation of WT insulin showed coprecipitation of UGGT1 that was lost in the presence of arginine. R46Q insulin maintains interaction with UGGT1 even in the presence of arginine. In contrast, three mutants involving the ring structure failed to interact with UGGT1 even in the absence of arginine, indicating that these residues are critical for the interaction of proinsulin with UGGT1 in the absence of arginine at the ER (Fig. 1e and S1e). Collectively, proinsulinWT is bound to UGGT1 in the absence of arginine and released from UGGT1 upon arginine administration, promoting secretion. In contrast, a MODY 10 variant of proinsulinR46Q is capable of binding to UGGT1 under arginine depletion but is unable to be released by arginine, preventing arginine-induced secretion of R46Q-insulin secretion.

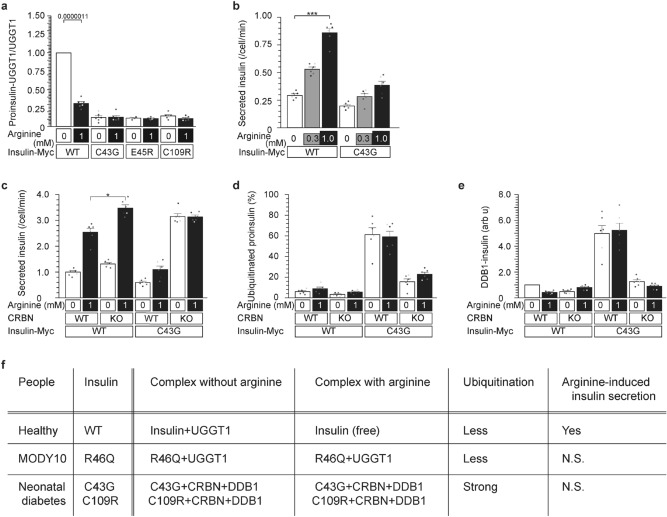

Impaired UGGT1-interaction in the C43G-neonatal diabetes variant (Figs. 2 and S2)

Figure 2.

Impaired UGGT1-interaction in the C43G-neonatal diabetes variant. (a) Impaired interaction of mutant insulin and UGGT1. WT, C43G, E45R, and C109R insulin were analyzed for their interaction with UGGT1 by immunoprecipitation (Fig. S2a). All three variants and mutants of acidic amino acid rings failed to bind to UGGT1 in the presence or absence of arginine. (b–e) Variant MODY10C43G, a mutation at the acidic amino acid ring, promotes degradation by CRBN and blunts secretion in response to arginine. Arginine-induced insulinC43G secretion was blunted in CRBNWT and CRBNKO cells (b and c). Ubiquitination of the insulinC43G protein and association with DDB1 were observed only in CRBNWT cells (d, e, Fig. S2a,b). (f) Summary of the interaction of insulin (R46Q and C43G variants) with UGGT1 and CRBN in the presence and absence of arginine.

Next, we performed further characterization of three mutants of acidic amino acids that form ring structures around the R46 residue, C43G, E45R and C109R (Figs. 1b,e and S1a,d). When proinsulinWT showed binding to UGGT1 only in the absence of arginine, none of three mutants (C43G, E45R, or C109R) showed binding to UGGT1 either in the presence or absence of arginine, indicating that they may not be retained at the ER where UGGT1 resides (Fig. 2a).

We previously reported that arginine prevents the degradation of glucokinase by the E3 ubiquitin ligase cereblon (CRL4CRBN) using cereblon KO cells23. Thus, we tested whether degradation of proinsulinC43G is increased and mediated by cereblon. Indeed, proinsulinC43G showed ubiquitination only in NIT cells expressing cereblon (Figs. 2d and S2a). We previously reported that cereblon interacts with damage-specific DNA binding protein 1 (DDB120,) for ubiquitination because they are two components of cullin ring ubiquitin ligase 4 (CRL4). In agreement with the interaction of proinsulinC43G with cereblon, proinsulinC43G interacted with DDB1 in cereblon+ cells but not in cereblon-KO cells (Figs. 2d and S2c) in the presence or absence of arginine. Then, we analyzed whether CRL4CRBN contributes to arginine-induced C43G-insulin secretion (Figs. 2b–d and S2a,b). The secretion of C43G mutant insulin in response to arginine was blunted compared with WT insulin in NIT1 cells expressing cereblon (Fig. 2b,c). The impairment in arginine-induced insulin secretion was not rescued by cereblon knockout in NIT1 cells expressing the C43G variant (Figs. 2c and S2b).

Collectively, these data indicated that proinsulinC43G interacts with cereblon and DDB1 instead of UGGT1, which leads to ubiquitination of proinsulinC43G by cereblon and subsequent degradation (Fig. 2e). Both proinsulinWT and proinsulinR46Q interact with UGGT1 in the absence of arginine (Fig. 2e). Whereas proinsulinWT is released from UGGT1 and secreted when arginine becomes available, the R46Q variant does not compete with arginine and remains bound to UGGT1, leading to ER retention and reduced secretion (Fig. 2e).

Based on two mutants, we propose that R46 and C43 residues of proinsulin have a distinct role in mediating arginine-induced insulin secretion. The R46 residue competes with arginine for the interaction with UGGT1, and the C43 residue mediates binding regardless of the availability of arginine. Thus, two variants (R46Q and C43G) responsible for MODY and neonatal diabetes cause impaired arginine-induced insulin secretion due to altered interaction with UGGT1.

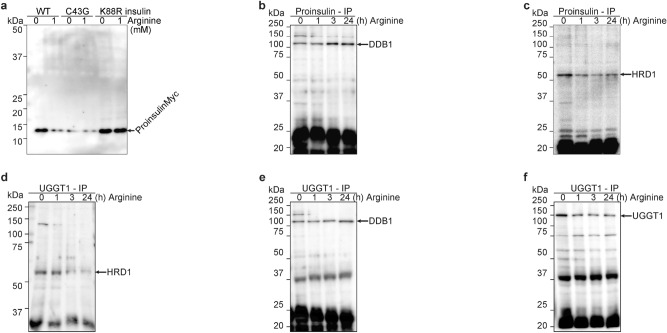

Arginine switches proinsulin associated E3 ubiquitin ligases from HRD1 to cereblon (Figs. 3 and S3)

Figure 3.

Arginine switches proinsulin associated E3 ubiquitin ligases from HRD1 to CRBN. (a) WT proinsulin was degraded after arginine administration, and C43G proinsulin was degraded with/without arginine, although K88R proinsulin was not degraded with/without arginine. Arginine was depleted for 30 min, and cells were treated with 0 or 1 mM arginine. The cell lysates were visualized with anti-Myc WB. (b–f) Both proinsulin and UGGT1 are associated with the E3 ubiquitin ligase DDB1 after arginine administration. Arginine was depleted from the medium for 30 min, and NIT1 cells were treated with 1 mM arginine for the indicated times (0, 1, 3, and 24 h). The cell lysates were IPed with proinsulin (b and c) or UGGT1 (d–f), and then these IP-ed lysates were visualized with DDB1 (b, and e), HRD1 (c and d), or UGGT1 (f, control).

In Fig. 2, we demonstrate that UGGT1 not only retains proinsulin in the ER but also protects proinsulin from ubiquitination and degradation by CRL4CRBN. This protection is releasing by arginine-replacing. Ubiquitination occurs on the lysine residue of K88-proinsulin. Non-ubiquitinated K88R-proinsulin actually existed at much higher levels than WT-proinsulin (Fig. 3a). This indicates that WT proinsulin in the ER is ubiquitinated and degraded. Non-ubiquitinated proinsulin K88R was secreted much more highly than WT proinsulin (Fig. S3a).

Proinsulin is one of the forms of insulin in the ER and the Golgi body1,2, leading to proinsulin ubiquitination called ERAD (ER-associated degradation). The main E3 ubiquitin ligase in ERAD is thought to be HRD1 (HMG-CoA reductase degradation protein 1)16–18. Other E3 ubiquitin ligases, CRL4 (CUL4-DDB1-CRBN), also include proinsulin ubiquitination (Fig. 2). First, arginine-induced proinsulin ubiquitination enzymes were investigated (Fig. 3b,c). Arginine administration induces proinsulin-associated DDB1 (Fig. 3b); nevertheless, arginine administration reduces proinsulin-associated HRD1 (Fig. 3c). On the other hand, UGGT1-associated E3 ubiquitin ligases were also analyzed. UGGT1 was also associated with DDB1 after arginine administration (Fig. 3d), but HRD1 dissociated after arginine administration (Fig. 3e). In fact, proinsulin and UGGT1 were mainly degraded after arginine administration (Fig. 3a and f), indicating that CRL4 (CUL4-DDB1-CRBN) is the E3 ubiquitin ligase that ubiquitinates and degrades proinsulin and UGGT1 after arginine administration. Cereblon colocalizes with UGGT1 in the ER with UDP-glucose and arginine (Fig. S3b).

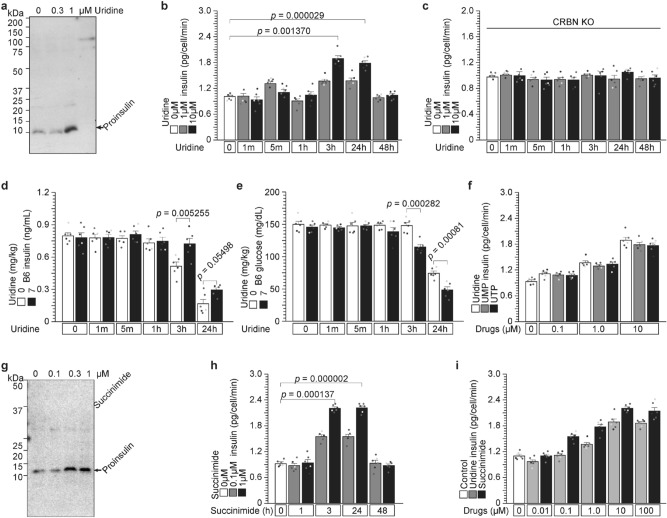

Uridine and succinimide protect proinsulin degradation from cereblon and stimulate insulin secretion from 3 to 24 h (Figs. 4 and S4)

Figure 4.

Uridine and succinimide protect proinsulin degradation from cereblon and stimulate insulin secretion from 3 to 24 h. (a–e) Uridine binds to cereblon and protects against proinsulin degradation by endogenous ligand X. (a) Uridine protects against proinsulin degradation in a dose-dependent manner. NIT1 cells were treated with 0, 0.3, or 1 µM uridine for 3 h. Intracellular proinsulin was detected by WB. (b and c) Uridine administration to NIT1 cells stimulates insulin secretion from 3 to 24 h with a cereblon contribution. Uridine was administered to CRBN-WT (b) and CRBN-KO (c) cells, and insulin secretion was analyzed using ELISA from 1 m to 48 h. (d and e) Uridine (7 mg/kg) administration to C57/BL6J mice induces circulating insulin (d) and reduces circulating glucose (e) from 1 m to 24 h. (f) Other uridine-containing compounds, UMP and UTP, stimulate insulin secretion from 3 to 24 h. (g–i) Succinimide also binds to cereblon and protects against proinsulin degradation. (g) Succinimide protects against proinsulin degradation in a dose-dependent manner. NIT1 cells were treated with 0, 0.1, 0.3, and 1 µM succinimide for 3 h. (h and i) Succinimide administration to NIT1 cells stimulated insulin secretion from 3 to 24 h in a dose-dependent manner.

Therefore, we demonstrate that UGGT1 protects against proinsulin ubiquitination by CRL4 (CUL4-DDB1-CRBN), and arginine administration releases this protective effect (Fig. 3), indicating that arginine-induced insulin secretion is a new step in inducing proinsulin degradation. If, this degradation is reduced, stimulating insulin secretion as a drug target such as K88R-insulin (Figs. 3a and S3a).

How repress cereblon-dependent ubiquitination? Cereblon is ligand-induced E3 ubiquitin ligase. First identified exogenous ligand is thalidomide20. Its substrate (ubiquitinated) protein is Ikaros26. A possible endogenous ligand is uridine24, but its substrate protein is not known. MEIS2 has been identified as an unknown endogenous/natural ligand A by competing with thalidomide26. Another exogenous ligand is succinimide24. cereblon-binding chemicals, such as uridine and succinimides, bind to cereblon and compete for endogenous/natural ligand A or proinsulin degrader X (Fig. S4c).

First, we administered uridine to NIT1 cells (Fig. 4a–c) and C57BL/6 J mice (Fig. 4d,e). Uridine released proinsulin degradation by endogenous proinsulin degrader X and increased proinsulin protein levels in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4a). Surprisingly, uridine-induced insulin secretion occurs from 3 to 24 h (Fig. 4b), because general insulin secretions, such as glucose and arginine, induce insulin secretion in minutes22,23. This induction was not observed after 1–5 min or in cereblon KO cells (Fig. 4b,c), indicating that uridine-competitive proinsulin degradation occurs through CRL4CRBN. Uridine administration to C57BL6 mice also induced insulin and reduced glucose concentrations from 3 to 24 h (Fig. 4d,e). There was no insulin induction immediate early of 1 and 5 min after administration in cells as well as WT-mice (Fig. 4b–e). Taken together, uridine-induced insulin secretion starts late and sustainably. Note that other uridine-containing chemicals, UMP and UTP, also induced insulin secretion (Fig. 4f) sustainably.

We have used CRBNYWAA mutant without thalidomide binding activity (1 and Fig. S4a). Glutarimides of immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs), thalidomide, lenalidomide, and pomalidomide, bind to cereblon, although IMiDs do not bind to cereblonYWAA (Fig. S4a). IN fact, uridine and UDP-glucose contain glutarimide structure (Fig. S4a). So, using CRBNYWAA mutant, UDP-glucose dependent UGGT1 degradation was analyzed, and CRBNYWAA mutant protein was resistant UDP-glucose triggering UGGT1 degradation (Fig. S4b,c). UDP-glucose bound to cereblon similar way to IMiDs, and induced UGGT1 degradation.

Succinimide (Fig. 4g–i) is an artificial cereblon-binding chemical24 and is a smaller molecule than uridine. Succinimide might not have a substrate protein-binding motif and has a higher affinity for cereblon than uridine24, indicating that succinimide may behave as a stronger cereblon inhibitor and stimulate insulin secretion than uridine. In fact, succinimide binds to cereblon, protects proinsulin degradation from proinsulin degrader X in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4g), and sustainably stimulates insulin secretion (Fig. 4h). Succinimide stimulates insulin secretion more than uridine does (Fig. 4i). The IC50 of succinimide was 1.541 μM (Fig. S4a), and the IC50 of uridine was 0.3473 μM (Fig. S4b).

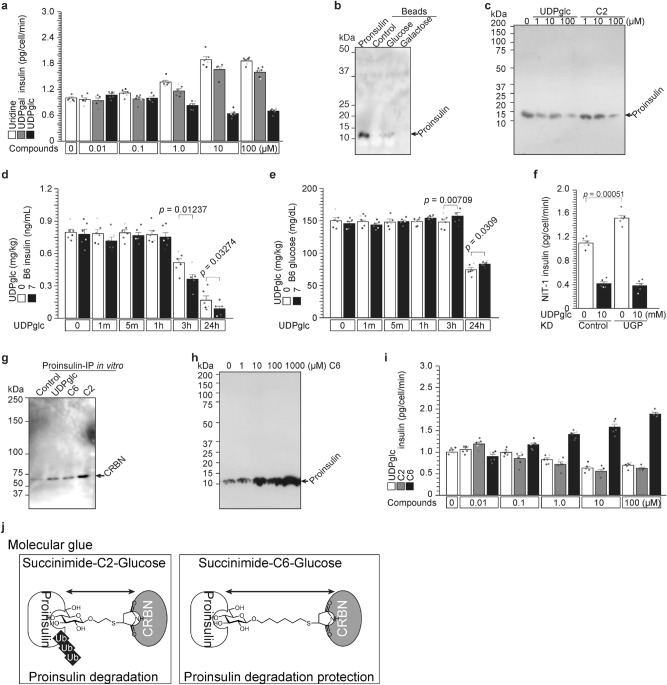

UDP-glucose is an endogenous proinsulin protein degrader through cereblon (Figs. 5 and S5)

Figure 5.

UDP-glucose is an endogenous proinsulin protein degrader through cereblon. (a–c) The proinsulin protein degrader X is UDP-glucose. Uridine and UDP galactose administration increased insulin secretion (Fig. 4), although UDP glucose decreased insulin secretion in a dose-dependent manner (a). Proinsulin binds to glucose but does not bind to galactose (b). UDP glucose and succinimide-C2-glcuose degraded proinsulin protein (c). (d and e) Administration of the proinsulin protein degrader UDP-glucose to C57/BL6J mice decreased circulating insulin (d) and increased glucose concentration (e). (f) Significant higher insulin secretion in UGP KD cells31. (g–j) Succinimide-glucose degrades or protects proinsulin. (g) Succinimide-C2-glucose strongly stimulates the proinsulin and cereblon interaction in vitro. (h) Succinimide-C6-glucose protects endogenous UDP-glucose-dependent proinsulin degradation in a dose-dependent manner. (i) UDP glucose and succinimide-C2-glucose reduced insulin secretion in a dose-dependent manner, although succinimide-C6-glucose induced insulin secretion (like UDP-galactose). (j) Possible model of molecular glue with/without proinsulin degradation.

We explored uridine monosaccharide to identify the proinsulin protein degrader X. Similar to uridine (Fig. 4), UDP-galactose also stimulated insulin secretion in β cells (Fig. 5a), while UDP-glucose repressed insulin secretion (Fig. 5a). These data indicated that UDP-glucose is the proinsulin degrader X, which degraded proinsulin in a dose-dependent manner. Uridine binds to cereblon (Fig. 4), and glucose weakly binds to proinsulin (Fig. 5b). Nevertheless, galactose does not bind to proinsulin (Fig. 5b). These data suggested that UDP-glucose combined with CRL4CRBN and proinsulin as a molecular glue. UDP-glucose administration to NIT1 cells reduced proinsulin in a dose-dependent manner (Figs. 5c and S5b–d, IC50 = 1.322 μM). UDP-glucose administration to C57/BL6J mice reduced insulin concentrations (Fig. 5d) and induced glucose concentrations (Fig. 5e) from 3 to 24 h, not immediate early times of 1 and 5 min. Furthermore, uridine-induced insulin secretion and UDP-glucose-reduced insulin secretion were confirmed with high glucose condition of NIT-1 (Fig. S5k), MIN6, and RIN5-F cells (Fig. S5l).

UDP-glucose and cereblon degrade UGGT1 (Figs. 5 and S5)

Cereblon degrade UGGT1 as well (Figs. 3 and S3). UDP-glucose is also UGGT1 degrader. In vitro IP-WB was performed (Fig. S5a). Protein–protein interaction was observed without UDP-glucose, and UDP-glucose induced the interaction (Fig. S5a). Using KD of cereblon and HRD1, and cereblon concerned with UDP-glucose dependent UGGT1 degradation (Fig. S5b).

We used two mutant proteins (Fig. S5c), and one is GTF which defect glucose transfer activity29. CRBNYWAA mutant protein has less binding activity to thalidomide1 and as well as uridine (Fig. S4a–c). Near 384Y and 386 W, there are two tryptophan residues of 380 W and 400 W. These three tryptophan residues are indispensable for IMiDs binding30. In the UGGT1, we found similar three tryptophan region, and made mutant named UGGT13W>3A (Fig. S5c). Uridine or glucose binding activity of these three UGGT1 proteins were analyzed, and indicating that WT and GTF mutant proteins bound to uridine as well as glucose, although 3 W > 3A mutant did not bind neither uridine nor glucose (Fig. S5d). Cereblon-UGGT1 interaction was analyzed, and UDP-glucose induced interaction of CRBNWT (Fig. S5a and e), although did not induce interaction of CRBN3W>3A (Fig. S5e,f).

Intracellular UDP-glucose concentration of various cells was analyzed by metabolome analysis (Fig. S5g). The highest UDP-glucose concentration was in HEK293 cells and the lowest concentration in NCI-H929-1α cells. UDP-glucose was administered to these cells and the UGGT1 degradation was analyzed (Fig. S5i,j). Higher UDP-glucose (1 mM) was necessary to HEK293, and lower UDP-glucose (100 μM) was necessary for H929-1α cells.

UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (UGP) is the enzyme of UDP-glucose synthesis from glucose-1-phosphate (G1P) and UTP.

UGP was knocked down (KD) in NIT-1 cells31. UDP-glucose was administered to these cells, and insulin secretion was analyzed (Fig. 5f). Significantly higher insulin secretion was observed in UGP-KD cells, but secreted insulin reduction by UDP-glucose administration were similarly observed in control and UGP-KD NIT-1 cells (Fig. 4f). Taken together, UDP-glucose administration in pancreatic β-cells first induces an interaction between cereblon and proinsulin as the molecular glue and then induces ubiquitination and degradation of proinsulin. Degraded proinsulin also reduced insulin secretion.

UDP-glucose and succinimide-glucose degrade insulin (Figs. 5 and S5)

Succinimide binds to cereblon with higher affinity than uridine (Fig. 4, and24), indicating that succinimide-linker-glucose may behave as a proinsulin degrader. We synthesized two linker lengths (C2H4 and C6H12), and the linkers were combined with succinimide and glucose. Succinimide-C2-glucose (C2) and succinimide-C6-glucose (C6) were synthesized and analyzed. In vitro complex formation analysis showed that UDP-glucose and C6 stimulated complex formation rather weakly, and C2 stimulated complex formation strongly (Fig. 5g). UDP-glucose and C2 degraded proinsulin in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5c), although surprisingly, C6 induced proinsulin protein in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5h). These phenomena are reproducible for insulin secretion (Fig. 5i). UDP-glucose and C2 reduce insulin secretion, although C6 induces insulin secretion in a dose-dependent manner. Note: UDP-glucose-IC50 = 1.322 μM (Fig. S5b–d), C2-IC50 = 0.475 μM (Fig. S5e–g), C6-IC50 = 0.489 μM (Fig. S5h-j).

Discussion

Proinsulin ERAD by cereblon controlled by uridine and UDP-glucose

ER-associated protein degradation (ERAD) is one unfolded protein response (UPR) cascade that eliminates unfolded proteins. Generally, unfolded proteins in the ER are ubiquitinated by HRD1. The HRD1 ubiquitination system is controlled by oxidative stress. Here, we identify other E3 ubiquitin ligase CRL4CRBN. Cereblon is ligand-inducible E3 ubiquitin ligase. The first identified ligand is thalidomide, and the thalidomide-CRBN substrate protein is Ikaros21. In addition, we identified two types of CRBN ubiquitination signaling molecules: agonists (UDP-glucose) and antagonists (uridine). Both are endogenous chemicals that always exist in each cell. This indicates endogenous chemical control of the ERAD system. As described above, the existence of unfolding proteins triggers ERAD but does not control other molecules. This is the first evidence of endogenous chemicals controlling UPR and ERAD.

UDP-glucose-dependent proinsulin degradation

Not only unfolded proinsulinC43G mutated protein but also proinsulinWT protein were degraded by cereblon (Figs. 3 and 4). Endogenous cereblon ligand for proinsulin degradation is UDP-glucose (Fig. 5). So, most probably proinsulin is always degraded by endogenous UDP-glucose. Using UGP KD system, endogenous UDP-glucose was decreased31. Insulin secretion were increased by MGP-KD (Fig. 5f). The data indicated that endogenous UDP-glucose degraded proinsulin protein. Administrated uridine competed with endogenous UDP-glucose-dependent proinsulin degradation, and led to increasing insulin secretion (Fig. 4 and S4). So, not only uridine (Figs. 4a–f,i, S4d and S5j,k), but also administered UMP (Fig. 4f), UTP (Fig. 4f), and UDP-galactose (Fig. 5a,b) inhibited UDP-glucose-dependent proinsulin degradation.

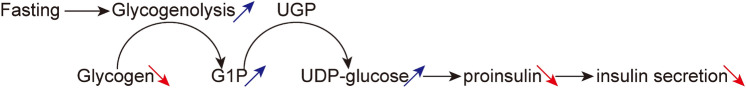

Possible physiological role of UDP-glucose-dependent proinsulin degradation

UDP-glucose is produced from G1P and UTP by UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (UGP, Fig. 5, and 31), and G1P is produced from glycogen by glycogenolysis 32. Glycogenolysis is the breakdown of glycogen (n) to G1P and glycogen (n-1). Glycogenolysis is mainly activated by fasting 32. Physiological role of UDP-glucose-induced proinsulin degradation might be one of the signaling under fasting (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Possible model of fasting induced UDP-glucose- and cereblon-dependent proinsulin degradation.

Preclinical study

Xu et al.(2018) reported preclinical study, using Akita mice with INS2C96Y/C96 (INS1C96/C96,33. This mouse insulin mutant disease is similar to rare disease MODY10 variant, dominant mutation. Here, we used insulinWT/WT, might be similar to type2 DM or aged people. Mutated protein (INS2C96Y) is generally recognized unfolded protein response (UPR), and eliminated with ER-associated protein degradation (ERAD) system with HRD1. Here, we identified other E3 ubiquitin ligase cereblon with UDP-glucose triggering.

Conclusion

We previously reported that proinsulin is retained in the ER through binding to the ER resident protein UGGT1 when the availability of arginine is low and that arginine releases proinsulin from the ER through competition with UGGT122. Here, we report MODY10- or neonatal diabetes-associated proinsulin variants that interfere with their interaction with UGGT1. Through the analysis of these variants, we further refined the molecular basis of the interaction between proinsulin and UGGT1. Proinsulin binds to UGGT1 via the R46 residue and amino acid residues that form a ring around R46 when the availability of arginine is low in the ER, causing the retention of proinsulin in the ER of pancreatic β cells. The C43, E45, and C109 residues of proinsulin form a ring structure that mediates the binding of proinsulin to UGGT1. In support of this hypothesis, C43G and C109R variants of proinsulin associated with neonatal diabetes failed to bind UGGT1. These variants bind the CRL4 E3 ubiquitin ligase of cereblon and DDB1 instead, leading to degradation after ubiquitination both in the presence and absence of arginine. This allows proinsulin to be further processed at the Golgi network and mature into secretory vesicles for insulin secretion. ProinsulinR46Q and proinsulinC43G genetic mutations associated with MODY/neonatal diabetes all cause impairment in arginine-inducing insulin secretion but cause distinct defects in the interaction between UGGT1 and proinsulin.

Free proinsulinWT also interacts with UDP-glucose and CRBN + DDB1 after dissociation from UGGT1 and is ubiquitinated. UDP-glucose and proinsulin are the first identified endogenous cereblon ligands and their substrate proteins.

This UDP-glucose-dependent proinsulin degradation is associated with linker length and is important. A shorter linker (C2) strengthens the complex, and proinsulin is degraded. A longer linker (C6) makes the complex weaker, but proinsulin is not ubiquitinated.

Using uridine or succinimide, proinsulin degradation by UDP-glucose and cereblon was inhibited, and insulin secretion was induced from 3 to 24 h (Fig. 4). Generally, insulin secretion stimulation is in minutes22,23. Insulin secretagoues (glucose, arginine, etc.) activate glucokinase activity and UGGT1 ER retention and stimulate insulin secretion immediately. Instead of acute induction by glucose or arginine, uridine, succinimide and succinimide-C6-glucose stimulation starts late and sustainably. They might be developing a new anti-diabetes drug.

Methods

Antibodies

The following antibodies were purchased: β-actin (sc-47778, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), insulin (L6B10, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA, and sc-9168, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), UGGT1 (14,170–1-AP, Proteintech, Rosemont, IL, USA; sc-374565, Santa Cruz Biotechnology; and ab13520-50, Abcam), and FLAG (F-1804, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). UGP knockdown siRNA (sc-154894) was purchased from Santa Cruz31.

Cells

Mouse β NIT-1 cells (CRL-2055TM purchased from ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA), human embryo kidney 293 T (HEK293T) cells and human hepatocellular carcinoma (Hep G2) cells were maintained as described previously16,17,22,23,25,26,34–36.

Analysis of insulin secretion from cells

Insulin secretion was determined using a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Shibayagi, Gunma, Japan)22,23 as described previously.

Immunoprecipitation (Ip) and Western blot (WB)

Ip and WB analysis were performed as described previously22,23,25,26,34–36. Immune complexes were detected using Immunostar LD (Wako) substrate. Signals were quantified with the LAS 4000 imaging system (GE Healthcare).

Structure analysis

Homology models of human proinsulin were generated using the Swiss-Model server. The template with the highest quality (2kqp.1; PDB ID: 2KQP)28 was selected for model building. Computer modeling of R46Q was performed using the PyMOL mutagenesis algorithm wherein the backbone-dependent rotamers of glutamine were examined. Only the rotamer with the highest frequency of appearance in proteins is shown. Global and per-residue model quality was evaluated using the QMEAN4 scoring function. The obtained scores were –5.83 and –6.06 for wild-type and mutant humans, respectively.

Proinsulin mutants

Using mutated synthesized oligomers and a PrimeSTAR mutagenesis basal kit (Takara, Kyoto, Japan), mutated insulin and UGGT1 expression vectors were produced. NIT-1 cells were transfected with pCDNA-insulin (WT, C43G, E45R, R46Q or C109R)-Myc expression vectors with Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher, Rockford, IL, USA). On the next day, these cells were cultivated in arginine-free medium for 30 min before arginine was added. The supernatants were analyzed with a Myc-ELISA kit (Shibayagi, Japan). The transfection efficiency was ~ 10% for NIT-1 cells and 80% for HEK293FT cells.

Chemical synthesis

General

1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl3-d and D2O using a Bruker AVANCE 400 Plus Nanobay instrument (400 and 101 MHz) and a Bruker AVANCE 500 instrument fitted with a cryoprobe (500 and 126 MHz), respectively. Chemical shifts (δ) are given in ppm and referenced to tetramethylsilane (0.00 ppm) or the internal solvent signal used as an internal standard. Assignments in the NMR spectra were made by first-order analysis of the spectra and were supported by 1H − 1H COSY and 1H − 13C HMQC correlation results. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight high-resolution mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF HRMS) spectra were recorded on a Jeol JMS-S3000 using 2,5-dihydroxylbenzoic acid as the matrix. Unless otherwise stated, all commercially available solvents and reagents were purchased from FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation and Tokyo Chemical Industry Company Limited without further purification.

2-Bromoethyl 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (2)

To a solution of compound 1 (3.00 g, 6.09 mmol) and 2-bromoethanol (743 μL, 10.4 mmol) in dichloromethane (28.4 mL) was added molecular seives 3 Å powder (3.00 g), and cooled at − 40 °C. To the mixture was added boron trifluoride-ethyl ether complex (229 μL, 1.82 mmol) diluted in dichloromethane (2.1 mL) and stirred at − 40 °C for 30 min. The solution was diluted with dichloromethane and filtered through celite. The filtrate was washed with aqueous sodium hydrogen carbonate and brine, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, filtered, and evaporated. The residue was purified by silica gel chromatography with 8:1 to 4:1 (v/v) hexane–ethyl acetate to give 2 (1.84 g, 66%): 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 5.22 (t, 1 H, J2,3 = 9.5 Hz, H-3), 5.09 (t, 1 H, J3,4 = 9.5 Hz, H-4), 5.02 (dd, 1 H, Hz, H-2), 4.58 (d, 1 H, J1,2 = 8.0 Hz, H-1), 4.58 (dd, 1 H, J = 4.8 Hz, J6a,6b = 12.3 Hz, H-6a), 4.20–4.13 (m, 2 H, H-6b, –OCH2–), 3.85–3.79 (m, 1 H, –OCH2–), 3.74–3.69(m, 1 H, H-5), 3.49–3.45 (m, 2 H, –CH2Br), 2.10 (s, 3 H, Ac), 2.08 (s, 3 H, Ac), 2.03 (s, 3 H, Ac), 2.02 (s, 3 H, Ac); 13C{1H} NMR δ (CDCl3, 101 MHz): 170.6, 170.2, 169.4, 169.4, 101.0, 72.6, 71.9, 71.0, 69.8, 68.3, 61.8, 29.8, 20.7, 20.6, 20.5.

6-Bromohexyl 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (3)

To a solution of compound 1 (3.00 g, 6.09 mmol) and 6-bromoethanol (2.49 mL, 10.3 mmol) in dichloromethane (28.4 mL) was added molecular sieves 4 Å powder (3.00 g) and cooled at − 40 °C. To the mixture was added boron trifluoride-ethyl ether complex (229 μL, 1.82 mmol) diluted in dichloromethane (2.1 mL) and stirred at − 40 °C for 30 min, at − 20 °C for 30 min and then at 0 °C for 30 min. The solution was diluted with dichloromethane and filtered through celite. The filtrate was washed with aqueous sodium hydrogen carbonate and brine, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, filtered, and evaporated. The residue was purified by silica gel chromatography with 10:1 to 3:1 (v/v) hexane–ethyl acetate to give 3 (2.06 g, 66%): 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 5.21 (t, 1 H, J2,3 = 9.5 Hz, H-3), 5.09 (t, 1 H, J3,4 = 9.7 Hz, H-4), 4.99 (dd, 1 H, Hz, H-2), 4.49 (d, 1 H, J1,2 = 8.0 Hz, H-1), 4.27 (dd, 1 H, J = 4.7 Hz, , J6a,6b = 12.3 Hz, H-6a), 4.14 (dd, 1 H, J5,6a = 2.4 Hz, H-6b), 3.91–3.85 (m, 1 H, − OCH2− ), 3.72–3.67 (m, 1 H, H-5), 3.51–3.46 (m, 1 H, − OCH2− ), 3.41 (t, 2 H, J = 6.8 Hz, − CH2Br), 2.11 (s, 3 H, Ac), 2.05 (s, 3 H, Ac), 2.03 (s, 3 H, Ac), 2.01 (s, 3 H, Ac), 1.89–1.82 (m, 2 H, − CH2− ), 1.62–1.55 (m, 2 H, − CH2− ), 1.46–1.32 (m, 4 H, − CH2− ); 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3,101 MHz) δ 170.7, 170.3, 169.4, 169.2, 100.8, 72.8, 71.7, 71.3, 69.9, 68.4, 62.0, 33.7, 32.6, 29.2, 27.7, 25.0, 20.7, 20.6, 20.6, 20.6.

2-S-Thioacetylethyl 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (4)

To a solution of compound 2 (500 mg, 1.10 mmol) and thioacetic acid (117 μL, 1.64 mmol) in N,N-dimethylformamide (3.67 mL) was added potassium carbonate (228 mg, 1.65 mmol) and stirred at room temperature for 12 h. The solution was diluted with ethyl acetate, washed with aqueous sodium hydrogen carbonate and brine, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, filtered, and evaporated. The residue was purified by silica gel chromatography with 4:1 (v/v) hexane–ethyl acetate to give 4 (492 mg, 99%): 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 5.21 (t, 1 H, J2,3 = 9.5 Hz, H-3), 5.09 (t, 1 H, J3,4 = 9.7 Hz, H-4), 4.99 (dd, 1 H, Hz, H-2), 4.53 (d, 1 H, J1,2 = 8.0 Hz, H-1), 4.26 (dd, 1 H, J = 4.8 Hz, , J6a,6b = 12.3 Hz, H-6a), 4.14 (dd, 1 H, J = 2.4 Hz, , J6a,6b = 12.3 Hz, H-6b), 4.01–3.95 (m, 1 H, –OCH2–), 3.73–3.68 (m, 1 H, H-5), 3.65–3.59 (m, 1 H, H-5, –OCH2–), 3.26–3.01 (m, 2 H, –CH2S), 2.34 (s, 3 H, SAc), 2.09 (s, 3 H, Ac), 2.08 (s, 3 H, Ac), 2.03 (s, 3 H, Ac), 2.01 (s, 3 H, Ac); 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 101 MHz) δ 195.2, 170.6, 170.2, 169.4, 169.3, 100.8, 72.7, 71.9, 71.1, 68.6, 68.3, 61.8, 30.5, 28.8, 20.7, 20.7, 20.6, 20.5.

6-S-Thioacetylhexyl 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (5)

To a solution of compound 3 (700 mg, 1.37 mmol) and thioacetic acid (146 μL, 1.79 mmol) in N,N-dimethylformamide (4.57 mL) was added potassium carbonate (284 mg, 2.05 mmol) and stirred at room temperature for 17.5 h. The solution was diluted with ethyl acetate, washed with water and brine, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, filtered, and evaporated. The residue was purified by silica gel chromatography with 8:1 to 4:1 (v/v) hexane–ethyl acetate to give 5 (561 mg, 83%): 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 5.20 (t, 1 H, J2,3 = 9.5 Hz, H-3), 5.09 (t, 1 H, J3,4 = 9.7 Hz, H-4), 4.98 (dd, 1 H, Hz, H-2), 4.49 (d, 1 H, J1,2 = 8.0 Hz, H-1), 4.27 (dd, 1 H, J = 4.7 Hz, , J6a,6b = 12.3 Hz, H-6a), 4.14 (dd, 1 H, J = 2.4 Hz, J6a,6b = 12.3 Hz, H-6b), 3.90–3.84 (m, 1 H, –OCH2–), 3.71–3.67 (m, 1 H, H-5), 3.50–3.44 (m, 1 H, H-5, –OCH2–), 2.85 (t, 2 H, J = 7.3 Hz –CH2S), 2.33 (s, 3 H, SAc), 2.09 (s, 3 H, Ac), 2.04 (s, 3 H, Ac), 2.03 (s, 3 H, Ac), 2.01 (s, 3 H, Ac), 1.59–1.52 (m, 4 H, –CH2–), 1.37–1.32 (m, 4 H, –CH2–); 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 101 MHz) δ 196.0, 170.7, 170.3, 169.4, 169.3, 100.8, 72.9, 71.8, 71.3, 69.0, 68.5, 62.0, 30.6, 29.4, 29.2, 29.0, 28.4, 25.3, 20.8, 20.7, 20.6, 20.6.

2-S-Ethyl-β-D-glucopyranose S-linked maleimide (6)37

A solution of 4 (50.0 mg, 111 μmol) in methanol (950 μL) was added to 28% NaOMe-MeOH (50 μL) and then stirred at room temperature for 1 h. Diaion™ SK1B was added to the solution for quenching and filtration and evaporation. The residue was dissolved in methanol (2.22 mL), Et3N (22 μL) and maleimide (53.9 mg, 555 μmol) were added, and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h. The solution was concentrated, and the residue was purified by silica gel chromatography with 50:1 to 5:1 (v/v) dichloromethane-methanol to give 6 (30.3 mg, 81%): 1H NMR (D2O, 400 MHz) δ 4.30 (d, 1 H, J1,2 = 8.0 Hz, H-1), 3.98–3.90 (m, 2 H, –CH2SCH–, –OCH2–), 3.75–3.72 (m, 2 H, H-6, –OCH2–), 3.53 (dd, 1 H, J5,6a = 6.0 Hz, , J6a,6b = 12.1 Hz, H-6), 3.31–3.25 (m, 2 H, H-3, H-5), 3.21–3.07 (m, 3 H, H-2, H-4, –SCHCH2–), 2.90–2.86 (m, 1 H, –CH2S–), 2.80–2.75 (m, 1 H, –CH2S–), 2.63–2.58 (m, 1 H, –SCHCH2–); 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 126 MHz) δ 180.9, 179.7, 102.3, 75.8, 75.5, 72.9, 69.4, 69.0, 60.6, 41.5, 41.4, 37.2, 30.3; MALDI-TOF HRMS m/z: [M + Na] + : Calcd for C12H19N1O8S1 + Na + : 360.0724; Found: 360.0676.

6-S-Hexyl-β-D-glucopyranose S-linked maleimide (7)37

A solution of 5 (50.0 mg, 101 μmol) in methanol (950 μL) was added to 28% NaOMe-MeOH (50 μL) and then stirred at room temperature for 2.5 h. Diaion™ SK1B was added to the solution for quenching, filtration, and evaporation. The residue was dissolved in methanol (2.02 mL), Et3N (20 μL) and maleimide (49.0 mg, 505 μmol) were added, and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h. The solution was concentrated, and the residue was purified by reverse-phase C18 silica gel chromatography with 1:0 to 4:1 (v/v) H2O-CH3CN to give 6 (27.5 mg, 72%): 1H NMR (D2O, 500 MHz) δ 4.32 (d, 1 H, J1,2 = 8.0 Hz, H-1), 3.98–3.93–3.90 (m, 1 H, –CH2SCH–), 3.82–3.78 (m, 2 H, H-6a, –OCH2–), 3.61–3.52 (m, 2 H, H-6b, –OCH2–), 3.38–3.30 (m, 2 H, H-3, H-5), 3.27–3.10 (m, 3 H, H-2, H-4, –SCHCH2–), 2.67–2.57 (m, 3 H, –SCHCH2–, –CH2S–), 1.52–1.47 (m, 4 H, –CH2–), 1.32–1.24 (m, 4 H, –CH2–); 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 126 MHz) δ 181.2, 179.9, 102.0, 75.8, 75.7, 73.0, 70.4, 69.5, 60.6, 41.4, 37.2, 30.0, 28.4, 28.1, 27.4, 24.4; MALDI-TOF HRMS m/z: [M + Na] + : Calcd for C16H27N1O8S1 + Na + : 416.1350; Found: 415.1309.

Statistical analysis

The values are reported as the means ± standard error (n = 6) with six individual data points. Statistical significance (single-sided Student’s t test) is indicated in the figure legends as follows: *p < 0.05. n = 6 for statistical analysis22,23,25,26,34–36.

Ethical approval

The study is reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines. All mouse experiments were performed in accordance with the ethical guidelines for animal care of National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology, and the experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Care Committee of National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology22,23,25,26,34–36.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to our department members at NCGG for their helpful discussions and Dr. N. Maekawa and M Umeda for technical assistance, Pr. T. Satoh at Nagoya City University for protein structure analysis, and Pr. T. Ito at Tokyo Medical University for CRBN KO cells.

Author contributions

J.C., A.M., K.Y., W.A., Y.T., and H.M. performed the experiments, T.I. designed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT 18659493), the Japan Science and Technology Agency (A-STEP-AS2312036G and FY2013-SICP) and NCGG (28–25, 19–7, 21–3) to TI.

Data availability

Requests for data and materials should be addressed to TI (timai@ncgg.go.jp).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-18902-5.

References

- 1.Rhodes, C. J., Shoelson, S., & Halban, P. A. Insulin biosynthesis, processing, and chemistry, Joslin’s Diabetes Mellitus Fourteenth Edition 2005 Chapter 5 (65–82) (2005).

- 2.Herquin, J.C. Cell biology of insulin secretion, Joslin’s Diabetes Mellitus Fourteenth Edition 2005 Chapter 6 (83–108) (Lippincott Williams and Wilkins) (2005).

- 3.Chen C, Cohrs CM, Stertmann J, Bozsak R, Speier S. Human beta cell mass and function in diabetes: Recent advances in knowledge and technologies to understand disease pathogenesis. Mol. Metab. 2017;6:943–957. doi: 10.1016/j.molnet.2017.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boland BB, Rhodes CJ, Grimsby JS. The dynamic plasticity of insulin production in beta-cells. Mol. Metab. 2017;6:958–973. doi: 10.1016/j.molnet.2017.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pueyo ME, Clement K, Vaxillaire M, Passa P, Froguel P, Robert JJ, Velho G. Arginine-induced insulin release in glucokinase-deficient subjects. Diabet. Care. 1994;17:1015–1021. doi: 10.2337/diacare.17.9.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Støy J, Edghill EL, Flanagan SE, Ye H, Paz VP, Pluzhnikov A, Below JE, Hayes MG, Cox NJ, Lipkind GM, Lipton RB, Greeley SA, Patch AM, Ellard S, Steiner DF, Hattersley AT, Philipson LH, Bell GI. Neonatal diabetes international collaborative group, insulin gene mutations as a cause of permanent neonatal diabetes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:15040–15044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707291104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meur G, Simon A, Harun N, Virally M, Dechaume A, Bonnefond A, Fetita S, Tarasov AI, Guillausseau PJ, Boesgaard TW, Pedersen O, Hansen T, Polak M, Gautier JF, Froguel P, Rutter GA, Vaxillaire M. Insulin gene mutations resulting in early-onset diabetes: marked differences in clinical presentation, metabolic status, and pathogenic effect through endoplasmic reticulum retention. Diabetes. 2010;59:653–661. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2015.39.6.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park SY, Ye H, Steiner DF, Bell GI. Mutant proinsulin proteins associated with neonatal diabetes are retained in the endoplasmic reticulum and not efficiently secreted. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010;391:1449–1454. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.12.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajan S, Eames SC, Park SY, Labno C, Bell GI, Prince VE, Philipson LH. In vitro processing and secretion of mutant insulin proteins that cause permanent neonatal diabetes. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010;298:E403–E410. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00592.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu M, Lara-Lemus R, Shan SO, Wright J, Haataja L, Barbetti F, Guo H, Larkin D, Arvan P. Impaired cleavage of preproinsulin signal peptide linked to autosomal-dominant diabetes. Diabetes. 2012;61:828–837. doi: 10.2337/db11-0878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guo H, Xiong Y, Witkowski P, Cui J, Wang LJ, Sun J, Lara-Lemus R, Haataja L, Hutchison K, Shan SO, Arvan P, Liu M. Inefficient translocation of preproinsulin contributes to pancreatic β cell failure and late-onset diabetes. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:16290–16302. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.562355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu M, Wright J, Guo H, Xiong Y, Arvan P. Proinsulin entry and transit through the endoplasmic reticulum in pancreatic beta cells. Vitam. Horm. 2014;95:35–62. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800174-5.00002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Støy J, Olsen J, Park SY, Gregersen S, Hjørringgaard CU, Bell GI. In vivo measurement and biological characterisation of the diabetes-associated mutant insulin p. R46Q (GlnB22-insulin) Diabetologia. 2017;60:1423–1431. doi: 10.1007/s00125-017-4295-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishi M, Nanjyo K. Insulin gene mutations and diabetes. J. Diabetes Investig. 2011;2:92–100. doi: 10.1111/j.2040-1124.2011.00100.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eames SC, Kinkel MD, Rajan S, Prince VE, Philipson LH. Transgenic zebrafish model of the C43G human insulin gene mutation. J. Diabet. Investig. 2013;4:157–167. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei J, Yanzhi Yuan L, Chen YX, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Yang Y, Peek CB, Diebold L, Yang Y, Gao B, Jin C, Melo-Cardenas J, Chandel NS, Zhang DD, Pan H, Zhang K, Wang J, He F, Fang D. ER-associated ubiquitin ligase HRD1 programs liver metabolism by targeting multiple metabolic enzymes. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:3659. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06091-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shrestha N, Liu T, Ji Y, Reinert RB, Torres M, Li X, Zhang M, Tang C-HA, Chih-Chi Andrew H, Liu C, Naji A, Liu M, Lin JD, Kersten S, Arvan P, Qi L. Sel1L-Hrd1 ER-associated degradation maintains β cell identity via TGF-β signaling. J. Clin. Invest. 2020;130:3499–3510. doi: 10.1172/JCI134874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tijun W, Zhang S, Jialiang X, Zhang Y, Sun T, Shao Y, Wang J, Tang W, Chen F, Han X. HRD1, an important player in pancreatic β-cell failure and therapeutic target for type 2 diabetic mice. Diabetes. 2020;69:940–953. doi: 10.2337/db19-1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi, Q., & Chen, L. Cereblon: A protein crucial to the multiple functions of immunomodulatory drugs as well as cell metabolism and disease generation. J. Immunol. Res. (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Ito T, Ando H, Suzuki T, Ogura T, Hotta K, Imamura Y, Yamaguchi Y, Handa H. Identification of a primary target of thalidomide teratogenicity. Science. 2005;327:1345–1350. doi: 10.1126/science.1177319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fischer ES, Böhm K, Lydeard JR, Yang H, Stadler MB, Cavadini S, Nagel J, Serluca F, Acker V, Lingaraju GM, Tichkule RB, Schebesta M, Forrester WC, Schirle M, Hassiepen U, Ottl J, Hild M, Beckwith REJ, Harper JW, Jenkins JL, Thomä NH. Structure of the DDB1–CRBN E3 ubiquitin ligase in complex with thalidomide. Nature. 2014;512:49–53. doi: 10.1038/nature13527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho J, Hiramoto M, Masaike Y, Sakamoto S, Imai Y, ImaiY HH, Imai T. UGGT1 retains proinsulin in the endoplasmic reticulum in an arginine dependent manner. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020;527:668–675. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.04.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cho J, Horikawa Y, Enya M, Takeda J, Imai Y, Imai Y, Handa H, Imai T. L-Arginine prevents cereblon-mediated ubiquitination of glucokinase and stimulates glucose-6-phosphate production in pancreatic β-cells. Commun. Biol. 2020;3:497. doi: 10.1038/s42003-020-01226-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heim C, Pliatsika D, Mousavizadeh F, Bär K, Hernandez Alvarez B, Giannis A, Hartmann MD. De-novo design of cereblon (CRBN) effectors guided by natural hydrolysis products of thalidomide derivatives. J. Med. Chem. 2019;62(14):6615–6629. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Umeda M, Hiramoto M, Watanabe A, Tsunoda N, Imai T. Arginine-induced insulin secretion in endoplasmic reticulum. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015;466:717–722. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uebi T, Umeda M, Imai T. Estrogen induces Estrogen Receptor alpha expression and hepatocyte proliferation in the livers of the male mice. Genes Cells. 2015;20:217–223. doi: 10.1111/gtc.12214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ozturk MA, Kurtoglu S, Bastug O, Korkmaz L, Daar G, Memur S, Halis H, Günes T, Hussain K, Ellard S. Neonatal diabetes in an infant of diabetic mother: Same novel INS missense mutation in the mother and her offspring. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014;27(7–8):745–748. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2013-0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang Y, Hua QX, Liu J, Shimizu EH, Choquette MH, Mackin RB, Weiss MA. Solution structure of proinsulin: Connecting domain flexibility and prohormone processing. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:7847–7851. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C109.084921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Satoh T, Song C, Zhu T, et al. Visualization of a flexible modular structure of the ER folding-sensor enzyme UGGT. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:12142. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-12283-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamamoto J, Ito T, Yamaguchi Y, Handa H. Discovery of CRBN as a target of thalidomide: A breakthrough for progress in the development of protein degraders. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022 doi: 10.1039/d2cs00116k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cho J, Miyagawa A, Yamaguchi K, Abe W, Tsugawa Y, Yamamura H, Imai T. UDP-glucose: A cereblon-dependent glucokinase protein degrader. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23:9094. doi: 10.3390/ijms23169094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harris, R. A., Crabb, D. W. Metabolic interrelationships, Textbook of biochemistry with clinical corrections (850–890) Sixth edition, Devlin editor, Wiley-Liss (2006).

- 33.Xu B, Allard C, Alvarez-Mercado AI, Fuselier T, Kim JH, Coons LA, Hewitt SC, Urano F, Korach KS, Levin ER, Arvan P, Floyd ZE, Mauvais-Jarvis F. Estrogens promote misfolded proinsulin degradation to protect insulin production and delay diabetes. Cell Rep. 2018;24(1):181–196. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Umeda M, Hiramoto M, Imai T. Partial hepatectomy induces delayed hepatocyte proliferation and normal liver regeneration in ovariectomized mice. Clin. Exp. Gastroenterol. 2015;8:175–182. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S80212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsugawa Y, Natori M, Handa H, Imai T. Estradiol accelerates liver regeneration through estrogen receptor α. Clin. Exp. Gastroenterol. 2019;12:331–336. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S214196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsugawa Y, Hiramoto M, Imai T. Estrogen induces estrogen receptor α expression and hepatocyte proliferation in late pregnancy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019;511:592–596. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.02.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stolz RM, Northrop BH. Experimental and theoretical studies of selective thiol-ene and thiol-yne click reactions involving n-substituted maleimides. J. Org. Chem. 2013;78:8105–8116. doi: 10.1021/jo4014436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Requests for data and materials should be addressed to TI (timai@ncgg.go.jp).