Abstract

yqxM is a Bacillus subtilis gene of unknown function residing in an operon with sipW, which encodes a signal peptidase, and tasA, which encodes an antibiotic protein secreted in a sipW-dependent manner. YqxM was undetectable during growth in a variety of rich media, including Luria-Bertani (LB) medium, or in minimal media or under heat shock or ethanol stress conditions but was synthesized and secreted during growth in LB medium supplemented with 1.2 M NaCl. Consistent with the possible involvement of sipW in YqxM secretion, inactivation of sipW prevented YqxM secretion. YqxM was produced and secreted in a sipW-dependent manner during growth in LB medium when the sequences upstream of yqxM were replaced with those of the inducible Pspac promoter. Coexpression of yqxM and sipW in Escherichia coli resulted in a decrease in the apparent molecular mass of YqxM, consistent with the removal of a signal peptide. These experiments suggest that YqxM production is induced by a high concentration of salt and that YqxM is secreted under the control of SipW. We hypothesize that during most conditions of growth, YqxM is present at very low levels or is not synthesized at all and that this low level or absence is due, at least in part, to posttranscriptional repression.

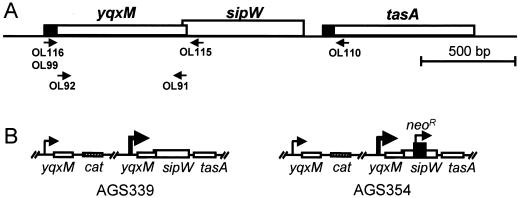

The ability to respond flexibly to a varying environment is essential to bacterial survival. Bacillus subtilis can respond to environmental challenges by spore formation, the uptake of foreign DNA (competence), the production of degradative enzymes and antibiotics, or the induction of a large set of general stress proteins (4, 5, 14). In previous work, we identified an operon, expressed during early-stationary-phase growth (12), consisting of yqxM, a gene of unknown function, sipW, which encodes a signal peptidase (15, 16), and tasA, which encodes an antibiotic protein which is secreted at the beginning of sporulation and is also built into the spore (11a, 13) (Fig. 1A). To date, TasA is the only candidate substrate for SipW in B. subtilis.

FIG. 1.

yqxM sipW tasA locus and Pspac-driven constructs. (A) The open boxes indicate genes, and the closed boxes at the 5′ ends of yqxM and tasA indicate potential signal peptide sequences. The directions of transcription are from left to right. Arrows underneath the genes indicate the binding sites of primers used in this study. (B) On the left, yqxM, sipW, and tasA are under the control of Pspac (thick arrow), as in strain AGS339. On the right, sipW has been inactivated by the introduction of a neomycin resistance gene (neo), resulting in strain AGS354. The thin arrows indicate the likely locations of an endogenous promoter (in front of yqxM), and the arrow above the neomycin resistance gene indicates its promoter and direction of transcription. The plasmid-borne cat marker is shown.

There is no readily observable phenotype when yqxM is deleted (13), and the predicted product of yqxM does not resemble any other proteins in the databases although it possesses a potential signal peptide at its N terminus (10). To begin to determine the role of YqxM, we have investigated the conditions for YqxM synthesis and secretion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General methods and detection of YqxM during growth.

Strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotide primers are described in Tables 1 and 2. Media and methods for the growth, sporulation by exhaustion, and genetic manipulation of B. subtilis are described in reference 2, and methods for cloning in Escherichia coli DH5α are described in reference 11. To identify conditions for the synthesis of YqxM, we grew cells in one of a variety of media for up to 48 h; prepared cell lysates, spore extracts, and culture supernatants; and subjected these to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (13). We then carried out Western blot analysis according to the method described in reference 13, except that 5% dry milk was used as the blocking reagent. Anti-YqxM antibody was used at a dilution of 1:7,500. We used the following media and growth conditions: incubation at 37, 42, or 52°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (11); incubation at 37°C in 2× YT, Terrific broth (11), King’s B medium (7) (in which sporulation is inhibited), or Difco sporulation medium (in which the majority of cells sporulate) (data not shown); incubation at 37°C in LB medium supplemented with 0.65, 0.7, 0.8, 1.2, or 1.4 M NaCl or with 2.5 or 10% ethanol; or incubation at 37°C in synthetic minimal medium (1). To analyze the synthesis of YqxM and TasA during growth with high concentrations of salt, we grew cells to stationary phase in LB medium, diluted the culture to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1 in LB medium with 1.2 M NaCl, and continued growth at 37°C. We then prepared cell extracts and concentrated culture supernatants at various times and analyzed them by Western blotting as described above. We used anti-TasA antibodies at a dilution of 1:10,000 (13).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids

| Strain or Plasmid (species) | Descriptiona | Reference, source, or construction |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| PY79 (B. subtilis) | Wild type | 19 |

| AG518 (B. subtilis) | abr::Tn917 trpC2 pheA1 | A. D. Grossman |

| AG839 (B. subtilis) | Δabr::cat trpC2 pheA1 | A. D. Grossman |

| AGS157 (B. subtilis) | sipWΔ::neo← | 13 |

| AGS175 (B. subtilis) | yqxM::neo→ | 13 |

| AGS339 (B. subtilis) | yqxMΩpAGS52 | This study |

| AGS347 (B. subtilis) | abrB::Tn917 | PY79 × DNA AG518 |

| AGS348 (B. subtilis) | ΔabrB::cat | PY79 × DNA AG839 |

| AGS354 (B. subtilis) | yqxMΩpAGS52 ΔsipW::neo→ | AGS339 × pAGS17-2 |

| AGS40 (E. coli) | BL21(DE3)/pET24b | This study |

| AGS249 (E. coli) | BL21(DE3)/pAGS36 | This study |

| AGS253 (E. coli) | BL21(DE3)/pAGS05 | This study |

| AGS275 (E. coli) | BL21(DE3)/pAGS41 | This study |

| AGS406 (E. coli) | BL21(DE3)/pAGS65 | This study |

| DH5α (E. coli) | Cloning host | Lab collection |

| BL21(DE3) (E. coli) | Overproduction host | Lab collection |

| Plasmids | ||

| pAG58 | Pspac expression plasmid | 6 |

| pAGS05 | Overexpression plasmid | 13 |

| pAGS17-2 | Insertion deletion in sipW | 13 |

| pAGS36 | T7 control of proless yqxM | This study |

| pAGS41 | T7 control of yqxM | This study |

| pAGS52 | Pspac control of yqxM | This study |

| pAGS65 | T7 control of yqxM and sipW | This study |

| pET24b | Overexpression plasmid | Novagen |

Arrows above gene names indicate directions of transcription.

TABLE 2.

Primersa

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence | Restriction endonuclease(s) | Nucleotide positions |

|---|---|---|---|

| OL91 | 5′ AAAAAAAAACTCGAGCTGATCAGCTTCATTGCT 3′ | XhoI | 741–758 |

| OL92 | 5′ AAAAAAAAACATATGTGCTTACAATTTTTC 3′ | NdeI | 99–114 |

| OL99 | 5′ AAAAACTCGAGCATATGTTTCGATTGTTTCAC 3′ | XhoI/NdeI | 1–18 |

| OL110 | 5′ AAAAAAGCGGCCGCCCTCCAACTAAAGCTAATCCTAGTG 3′ | NotI | 1424–1448 |

| OL115 | 5′ AAAAAAGCGGCCGCATGCTGAACGTGTTGAAATCACGAC 3′ | NotI/SphI | 808–818 |

| OL116 | 5′ AAAAAAGCTAGCATGTTTCGATTGTTTCAC 3′ | NheI | 1–18 |

The restriction endonuclease site(s) in each oligonucleotide is underlined (or in boldface), and the enzyme that cuts it is listed. For OL99, the XhoI site is underlined and the NdeI site is in boldface, and for OL115, the NotI site is underlined and the partially overlapping SphI site is in boldface. The region of the chromosome bound by each oligonucleotide is indicated as nucleotide positions relative to the start site of the yqxM open reading frame (9).

Overproduction of YqxM in E. coli and creation of an anti-YqxM antiserum.

We used PCR and the primers OL92 and OL91 to generate a DNA fragment beginning 99 nucleotides into the yqxM open reading frame (Fig. 1A) (and, therefore, missing most of the sequence encoding the putative signal peptide) and subcloned this fragment into the overexpression plasmid pAGS05 (13), adding six histidine codons to the 3′ end of yqxM. We transformed E. coli BL21(DE3) with the resulting plasmid (pAGS36), induced expression with IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) according to the directions supplied by Novagen, and prepared overproduced protein as described previously (13). We then lysed the cells by passing them twice through a French press (at 18,000 lb/in2), isolated the overproduced YqxM from the lysate by nickel chromatography using His-Bind resin (Novagen), and injected about 200 μg of the purified material into rabbits (3).

Pspac-driven expression of the locus.

To place yqxM, sipW, and tasA under the control of the inducible Pspac promoter (18), we first used PCR and the primers OL116 and OL115 to create a fragment of DNA beginning at the first codon of the yqxM open reading frame and ending 67 bp 3′ of yqxM (Fig. 1A). We digested the PCR product and pAG58 (6) with NheI and SphI and ligated these DNA fragments. We introduced the resulting plasmid (pAGS52) into the B. subtilis genome by Campbell-type single reciprocal integration (2) at yqxM, creating strain AGS339. This operation placed all three genes of the operon under the direction of Pspac and separated the locus from potential upstream regulatory sequences (Fig. 1B). To delete sipW from strain AGS339 by marker replacement, we transformed this strain with linearized pAGS17-2 (13) (Fig. 1B). We confirmed both integration events using PCR analysis (data not shown). We induced Pspac-driven expression of yqxM, sipW, and tasA by the addition of 1 mM IPTG to cells during exponential-phase growth (after culturing in LB medium for 3 h), and prepared cell extracts as described previously (13).

Overproduction of YqxM in E. coli to test secretion and processing.

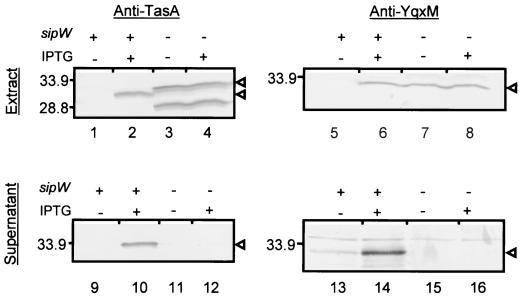

To overproduce YqxM or YqxM and SipW in E. coli (for the experiment whose results are shown in Fig. 4), we used PCR and the primers OL99 and OL91 or primers OL99 and OL110 to generate DNA fragments beginning at the first nucleotide of the yqxM open reading frame and ending at the last nucleotide of yqxM or ending 68 nucleotides downstream of sipW, respectively (Fig. 1A). We digested these fragments with NdeI and XhoI or with NdeI and NotI, respectively, subcloned them into appropriately digested pAGS05 or pET24b, respectively, and used the resulting plasmids to transform BL21(DE3). We induced expression of yqxM or yqxM and sipW by the addition of 1 mM IPTG for 0.75 h of growth in LB medium at 37°C. We then prepared cell extracts and concentrated culture supernatants, fractionated them by SDS-PAGE using 12% polyacrylamide gels, and performed Western blot analysis (13). In lanes 1 to 12 of Fig. 4, we loaded an amount of cell extract corresponding to 0.5 OD600 unit of the original culture, and in lanes 13 to 24, we loaded 200 μl of ethanol-precipitated culture supernatant. We used anti-acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) synthetase antibody, the kind gift of Alan Wolfe, at a dilution of 1:2,000. We used nucleotide sequencing to confirm that pAGS65 had no frameshift or nonsense mutations (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Western blot analysis of YqxM in E. coli. E. coli engineered to overproduce either YqxM (AGS275, lanes 2, 5, 8, 11, 14, 17, 20, and 23), YqxM and SipW (AGS406, lanes 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21, and 24), or no protein (AGS40, lanes 1, 4, 7, 10, 13, 16, 19, and 22) was grown without IPTG (lanes 1 to 3, 7 to 9, 13 to 15, and 19 to 21) or with IPTG (lanes 4 to 6, 10 to 12, 16 to 18, and 22 to 24), and cell extracts (lanes 1 to 12) and culture supernatants (lanes 13 to 24) were prepared. In each of lanes 1 to 8, we loaded an amount of cell extract corresponding to 0.5 OD600 unit of the original culture. For lanes 9 to 16, we loaded 200 μl of ethanol-precipitated culture supernatant (13). These preparations were subjected to electrophoresis on 12% polyacrylamide gels and Western blot analysis as described above. Samples were fractionated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes, and probed with anti-YqxM or anti-acetyl-CoA synthetase (Anti-Acs) antibodies. The three arrowheads adjacent to lane 6 indicate, from top to bottom, the immature form, the mature form, and a proteolytic product of YqxM. Molecular masses are indicated at the left of the gels in kilodaltons.

RESULTS

YqxM synthesis and secretion during growth with high concentrations of salt.

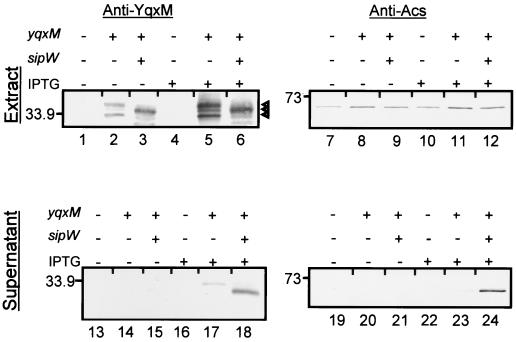

Surprisingly, we did not detect YqxM in cell lysates, spore extracts, or culture supernatants of B. subtilis grown under a wide variety of conditions, including growth in rich and minimal media and under heat and ethanol stress (see Materials and Methods and data not shown). However, we did detect YqxM in the culture supernatant, but not in cell extracts, during growth in LB medium supplemented with 0.65 to 1.2 M NaCl (results of growth with 1.2 M NaCl are shown in Fig. 2). YqxM first became detectable by Western blotting about 1 h prior to stationary phase and was present for at least 4 h (Fig. 2A and data not shown). We found that TasA became detectable at about the same time, as seen previously during growth in media with the standard concentration of NaCl (13) (data not shown). Under these conditions, YqxM migrated as a protein of approximately 38 kDa, similar to its apparent molecular mass when it was overproduced in E. coli (data not shown) but larger than the mass of about 24.5 kDa predicted from the sequence. Growth of the yqxM mutant strain (AGS175 [13]) was similar to that of the wild type during culture in either LB medium or LB medium with 1.2 M NaCl (13) (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Synthesis of YqxM during growth with high salt. (A) Wild-type cells (PY79) were grown in LB medium with 1.2 M NaCl. Culture at an OD600 of 0.2 was harvested at the indicated times ([T] in minutes) before or after the onset of stationary-phase growth, fractionated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes, and probed with anti-YqxM antibodies. The position of YqxM is indicated by an arrowhead. (B) Wild-type cells (PY79, lanes 1 and 2), yqxM mutant cells (AGS175, lanes 3 and 4), or sipW mutant cells (AGS157, lanes 5 and 6) were grown in LB medium with 1.2 M NaCl, and cell extracts (ext) (lanes 1, 3, and 5) and culture supernatants (sup) (lanes 2, 4, and 6) were prepared 16 h after the onset of stationary-phase growth. After fractionation by SDS-PAGE and transfer to PVDF membranes, blots were probed with anti-YqxM antibodies. The position of YqxM is indicated by an arrowhead. Molecular mass is indicated at the left in kilodaltons.

To learn whether sipW was required for YqxM secretion, we used Western blot analysis and anti-YqxM antibodies to examine cell extracts and culture supernatants prepared 16 h (Fig. 2B) after the beginning of stationary-phase growth, with LB medium containing 1.2 M NaCl. We found that the secretion of YqxM depended on sipW (Fig. 2B, compare lanes 2 and 6). We did not detect YqxM in extracts of sipW cells, suggesting that nonsecreted YqxM is rapidly proteolyzed.

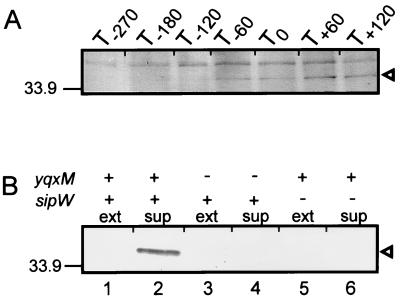

Pspac-driven yqxM expression permits YqxM synthesis.

The finding that YqxM synthesis is inhibited during growth conditions that permit expression of the operon (such as growth in LB medium [12]) suggested either that an upstream translational inhibitory sequence is present or that the level of yqxM message was insufficient for significant protein synthesis. To bypass both potential mechanisms, we placed yqxM, sipW, and tasA under the control of the inducible promoter Pspac (18), in a manner that uncoupled yqxM from the endogenous upstream sequences (in strains AGS339 and AGS354) (Fig. 1B). We then used Western blot analysis to determine the steady-state levels of YqxM and, as a control, TasA in these cells, when the cells were grown in LB medium. As expected from previous results, we found TasA in the cell extract and culture supernatants when IPTG was present (Fig. 3, lanes 2 and 10) (13). The secreted form of TasA migrated more slowly than TasA in cell extracts, possibly an effect of the culture supernatant on electrophoresis. We also detected YqxM in culture supernatants of these cells and, in contrast to what occurred with wild-type cells grown with high salt, in cell extracts (Fig. 2B, lane 1; Fig. 3, lanes 14 and 6). YqxM migrated as a protein of approximately 30 kDa, 8 kDa smaller than in cells grown with high salt or during overproduction in E. coli, possibly due to the action of a protease. The electrophoretic mobilities of YqxM in culture supernatants and in cell extracts were similar, suggesting that if YqxM is not secreted, it is cleaved at a position similar to that of secreted YqxM, towards the N terminus.

FIG. 3.

Western blot analysis of YqxM and TasA in cells with Pspac-induced synthesis. Cells with yqxM, sipW, and tasA expression under the control of Pspac (AGS339, lanes 1, 2, 5, 6, 9, 10, 13, and 14) or with yqxM under the control of Pspac, a mutation in sipW, and constitutive tasA expression (AGS354, lanes 3, 4, 7, 8, 11, 12, 15, and 16) were grown with IPTG (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, and 16) or without IPTG (lanes 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, and 15), and cell extracts (lanes 1 to 8) and culture supernatants (lanes 9 to 16) were prepared. After fractionation by SDS-PAGE and transfer to PVDF membranes, blots were probed with anti-YqxM (lanes 5 to 8 and 13 to 16) or anti-TasA (lanes 1 to 4 and 9 to 12) antibodies. The arrowheads adjacent to lane 4 indicate the immature (upper arrowhead) and the mature (lower arrowhead) forms of TasA. The arrowhead adjacent to lane 12 indicates the form of TasA found in the supernatant. The arrowheads adjacent to lanes 8 and 16 indicate YqxM. Molecular masses are indicated in kilodaltons.

It was possible that Pspac-driven expression of yqxM produced a protein due to an elevated level of message. To test this possibility, we analyzed strains bearing mutations in abrB (AGS347 and AGS348) which result in an approximately 15-fold derepression of tasA transcription (12). We did not detect YqxM in extracts of these cells by Western blot analysis (data not shown), which argues that increased transcription alone is probably insufficient to permit the appearance of YqxM. More likely, under most growth conditions, a posttranscriptional event represses the synthesis of YqxM. Although we have no data regarding ribosome binding, the Shine-Dalgarno sequence associated with yqxM is in perfect agreement with the B. subtilis consensus sequence (17).

To determine whether YqxM secretion is sipW dependent under these conditions of synthesis, we expressed yqxM in the absence of sipW (in strain AGS354) (Fig. 1B) and then used Western blot analysis to determine whether YqxM and, as a control, TasA, were present in extracts and supernatants of these cells. In this construct, tasA expression is constitutive (13) (Fig. 3, lanes 3 and 4). Consistent with the loss of SipW function, we detected the immature form of TasA in extracts and very little TasA in the supernatant (Fig. 3, lanes 3, 4, 11, and 12) (13). We observed YqxM in extracts of strain AGS354 but not in the culture supernatant (Fig. 3, lanes 7, 8, 15, and 16). Unexpectedly, YqxM was present in the sipW mutant strain when cells were grown without IPTG as well as with IPTG (Fig. 3, lanes 7 and 8). The reason for this result is unknown.

The above-described experiments established the dependency of YqxM secretion on sipW but did not permit us to visualize the expected change in YqxM mobility that should result from the cleavage of a signal peptide. Therefore, we examined SipW-dependent YqxM cleavage in E. coli. In cell extracts from an E. coli strain producing YqxM alone (AGS275), we detected a band of about 38 kDa as well as an approximately 33-kDa band that we suspect is the result of proteolytic cleavage (Fig. 4, lane 5). The presence of these bands in the absence of IPTG suggested some promoter activity even without IPTG (Fig. 4, lanes 2 and 3). In extracts from cells expressing yqxM and sipW (AGS406), we observed a band of approximately 35 kDa (Fig. 4, lane 3 and 6). This indicated that sipW was responsible for a decrease in the molecular mass of YqxM, consistent with the cleavage of the putative signal peptide. Presumably, the 35-kDa species had been translocated into the periplasm. The slight difference in mobility between the apparently secreted forms of YqxM in E. coli and in B. subtilis may reflect effects of the different cell extracts and supernatant on electrophoresis or different proteases in the two organisms.

We found some YqxM in the E. coli culture supernatant (Fig. 4, lanes 17 and 18). We hypothesized that this was the result of cell lysis and not translocation across the outer membrane. Consistent with this view, the levels of the cytoplasmic enzyme acetyl-CoA synthetase (8) (Fig. 4, lanes 23 and 24) reflected the levels of YqxM in the culture supernatant (Fig. 4, lanes 17 and 18).

DISCUSSION

Our results indicate that during growth with high salt, YqxM is produced and, in a sipW-dependent manner, secreted. Previously, we showed that the yqxM sipW tasA operon is transcribed during postexponential-phase growth (12), resulting in the SipW-dependent secretion of the antibacterial protein TasA (13). It seems likely that TasA provides a competitive advantage to cells in the soil during conditions of nutrient limitation. The present study suggests an additional role for the operon in adaptation to high levels of salt. The function of YqxM is unknown, but the lack of an obvious growth defect in yqxM mutant cells during growth with high salt argues against a direct role in protection from salt stress. Possibly, YqxM enables the cells to survive some additional environmental challenge concomitant with this stress in nature, much as we argue for TasA (13). An intriguing possibility is that YqxM is an antibiotic designed to function in the presence of elevated concentrations of salt.

We do not know how the 5′ end of the yqxM sipW tasA transcript participates in inhibition of YqxM synthesis during growth in rich media. Possibly, this portion of the message forms a structure or binds a protein that blocks access of the ribosome to the yqxM translational initiation site. Inhibition may be overridden by a posttranscriptional event that frees the translational initiation site or by use of an alternative transcriptional start site.

Our work also indicates that SipW can function in E. coli, an organism only distantly related to B. subtilis. This finding reinforces the notion that no additional specialized factors are required for SipW-dependent cleavage and further suggests that SipW participates in a mechanism of export that is relatively well conserved across species. The ability to study SipW activity and substrate specificity in a heterologous system may be advantageous in dissecting this secretory pathway and raises the intriguing question of whether SipW-like enzymes exist in E. coli. This study also demonstrates an approach for studying poorly characterized potential substrates of signal peptidases. By placing the gene for such a protein under the control of Pspac, the mechanism of secretion can be studied without any knowledge of the normal circumstances for its expression.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Alan Grossman for kind gifts of strains, Alan Wolfe for the anti-acetyl-CoA synthetase antibody, and Jean Greenberg, Shawn Little, and Jan Maarten van Dijl for critically reading the manuscript and for very helpful discussions. We also acknowledge the excellent technical assistance of Shawn Little and Dong Chae.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant GM539898 from the National Institutes of Health and the Schweppe Foundation. A.G.S. was funded, in part, by a Schmitt dissertation fellowship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antelmann H, Engelmann S, Schmid R, Sorokin A, Lapidus A, Hecker M. Expression of a stress- and starvation-induced dps/pexB-homologous gene is controlled by the alternative sigma factor ςB in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7251–7256. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.23.7251-7256.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cutting S M, Vander Horn P B. Molecular biological methods for Bacillus. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harlow E, Lane D. Antibodies: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hecker M, Schumann W, Volker U. Heat-shock and general stress response in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:417–428. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.396932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hecker M, Volker U. Non-specific, general and multiple stress resistance of growth-restricted Bacillus subtilis cells by the expression of the sigmaB regulon. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:1129–1136. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaacks K J, Healy J, Losick R, Grossman A D. Identification and characterization of genes controlled by the sporulation regulatory gene spoOH in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:4121–4129. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.8.4121-4129.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.King E O, Ward M K, Raney D E. Two simple media for the demonstration of pyocyanin and fluorescin. J Lab Clin Med. 1954;44:301–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumari S, Tishel R, Eisenbach M, Wolfe A J. Cloning, characterization, and functional expression of acs, the gene which encodes acetyl coenzyme A synthetase in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2878–2886. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.10.2878-2886.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kunst F, Ogasawara N, Moszer I, Albertini A M, Alloni G, Azevedo V, Bertero M G, Bessieres P, Bolotin A, Borchert S, Borriss R, Boursier L, Brans A, Braun M, Brignell S C, Bron S, Brouillet S, Bruschi C V, Caldwell B, Capuano V, Carter N M, Choi S K, Codani J J, Connerton I F, Danchin A, et al. The complete genome sequence of the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature. 1997;390:249–256. doi: 10.1038/36786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagarajan V. Protein secretion. In: Sonenshein A L, Hoch J, Losick R, editors. Bacillus subtilis and other gram-positive bacteria: biochemistry, physiology, and molecular genetics. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 11a.Serrano M, Zilhao R, Ricca E, Ozin A J, Moran C P, Jr, Henriques A O. A Bacillus subtilis secreted protein with a role in endospore coat assembly and function. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3632–3643. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.12.3632-3643.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stöver A G, Driks A. Regulation of the synthesis of the B. subtilis transition phase, spore-associated antibacterial protein TasA. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5476–5481. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.17.5476-5481.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stöver A G, Driks A. Secretion, localization, and antibacterial activity of TasA, a Bacillus subtilis spore-associated protein. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1664–1672. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.5.1664-1672.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strauch M A, Hoch J A. Transition-state regulators: sentinels of Bacillus subtilis post-exponential gene expression. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:337–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tjalsma H, Bolhuis A, van Roosmalen M L, Wiegert T, Schumann W, Broekhuizen C P, Quax W J, Venema G, Bron S, van Dijl J M. Functional analysis of the secretory precursor processing machinery of Bacillus subtilis: identification of a eubacterial homolog of archaeal and eukaryotic signal peptidases. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2318–2331. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.15.2318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tjalsma H, Noback M A, Bron S, Venema G, Yamane K, van Dijl J M. Bacillus subtilis contains four closely related type I signal peptidases with overlapping substrate specificities. Constitutive and temporally controlled expression of different sip genes. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25983–25992. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vellanoweth R L. Translation and its regulation. In: Sonenshein A L, Hoch J, Losick R, editors. Bacillus subtilis and other gram-positive bacteria: biochemistry, physiology, and molecular genetics. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yansura D G, Henner D J. Use of the Escherichia coli lac repressor and operator to control gene expression in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:439–443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.2.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Youngman P, Perkins J B, Losick R. Construction of a cloning site near one end of Tn917 into which foreign DNA may be inserted without affecting transposition in Bacillus subtilis or expression of the transposon-borne erm gene. Plasmid. 1984;12:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(84)90061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]