Abstract

The tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle aconitase gene acnA from Streptomyces viridochromogenes Tü494 was cloned and analyzed. AcnA catalyzes the isomerization of citrate to isocitrate in the TCA cycle, as indicated by the ability of acnA to complement the aconitase-deficient Escherichia coli mutant JRG3259. An acnA mutant was unable to develop aerial mycelium and to sporulate, resulting in a bald phenotype. Furthermore, the mutant did not produce the antibiotic phosphinothricin tripeptide, demonstrating that AcnA also affects physiological differentiation.

The structurally identical antibiotics phosphinothricin tripeptide (PTT) and bialaphos are produced by Streptomyces viridochromogenes Tü494 and S. hygroscopicus (1, 9), respectively. They consist of two molecules of l-alanine and one molecule of the unusual amino acid phosphinothricin. In both organisms, several proteins and genes involved in PTT biosynthesis have been characterized (4, 15, 16, 18). By analyzing bialaphos-nonproducing mutants of S. hygroscopicus, a putative biosynthetic pathway was postulated consisting of at least 13 biosynthetic steps (summarized in reference 18). In this pathway, the isomerization of phosphinomethylmalate (step 7) was found to be similar to the aconitase reaction of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and it was speculated that this step is catalyzed by the TCA cycle-specific enzyme reaction. All aconitases are characterized by a 4Fe-4S cluster at the catalytic site of the enzymes (5). Sequence analyzes of aconitase genes from several bacteria, plants, and fungi suggest the existence of two structural forms, called A and B, which differ in protein domain structure (5). Whereas in type A aconitases domain 4 is linked at the carboxy-terminal end of the protein, in type B aconitases domain 4 presents the amino terminus (5). The genes of both forms have been identified in several gram-negative bacteria, e.g., in Escherichia coli (5) and Helicobacter pylori (20). In this paper, we describe the isolation and characterization of the TCA cycle aconitase gene of S. viridochromogenes. Our results suggest that the aconitase is involved in the initiation of morphological and physiological differentiation in S. viridochromogenes.

Identification and characterization of the TCA cycle aconitase from S. viridochromogenes.

During the analysis of PTT biosynthesis in S. viridochromogenes, the PTT biosynthetic gene pmi (phosphinomethylmalate isomerase gene) was identified, whose deduced gene product has 48% overall identity to type A aconitases from E. coli and Legionella pneumophila (14a). A 2-kb internal EcoRI/SacI fragment of this gene was used to isolate the aconitase gene of the TCA cycle by Southern hybridization against a λ phage library of S. viridochromogenes (hybridization at 68°C using a DIG-DNA labeling kit [Boehringer]; stringent washing step with 0.5× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate]–0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate). Approximately 6,500 phage clones were examined, and 33 hybridizing clones were isolated. One phage clone (λ-ACN2) was characterized that carries a 1.6-kb hybridizing SacI DNA fragment which is not found in the pmi locus of the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster. The hybridizing SacI fragment and adjacent overlapping DNA fragments of λ-ACN2 were subcloned in vector pUC18, and the nucleotide sequence of a 4.3-kb DNA fragment was determined. The analysis of this sequence by the codon usage program of Staden and McLachlan (17) led to the identification of a single complete open reading frame on one strand and an incomplete open reading frame on the opposite strand named acnA and murA′, respectively. murA is located upstream of acnA (Fig. 1) and encodes a protein with similarity to MurA (UDP-N-acetylglucosamine enolpyruvoyl transferase) from different bacteria. By cloning of a 0.7-kb PvuII/BglII fragment in the promoter probe vectors pIJ486 and pIJ487, divergent DNA regions capable of promoting transcription initiation were identified on this fragment (Fig. 1). By homology search, the deduced AcnA protein with 931 amino acids clearly resembled type A aconitases from bacteria, plants, and fungi, such as AcnA of E. coli (55% overall identity) and Bacillus subtilis (50% overall identity). The highest similarity was found to the aconitases of S. coelicolor (17a) and Mycobacterium avium (10) with identities of 89 and 66%, respectively. Conserved amino acid residues involved in the formation of the 4Fe-4S cluster typical of this kind of enzyme (3) were identified in the deduced AcnA amino acid sequence (Fig. 2).

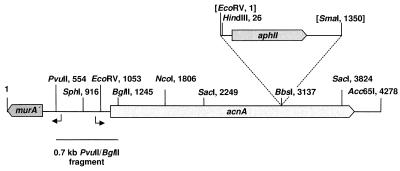

FIG. 1.

Genetic localization and gene insertion mutagenesis of the aconitase gene acnA. The genetic organization of a 4.3-kb DNA fragment of λ-ACN2 carrying the acnA gene is shown. acnA, gene encoding the TCA aconitase AcnA; murA′, 3′ terminus of a murA-like gene from S. viridochromogenes. Restriction sites used in subcloning experiments are marked, and regions with promoter activity are indicated by arrows. The kanamycin resistance cassette (aphII gene from transposon Tn5) and insertion sites used for inactivation of the acnA gene are shown. Restriction sites destroyed by insertion of the cassette are bracketed. The 0.7-kb PvuII/BglII fragment used in promoter probe experiments is marked.

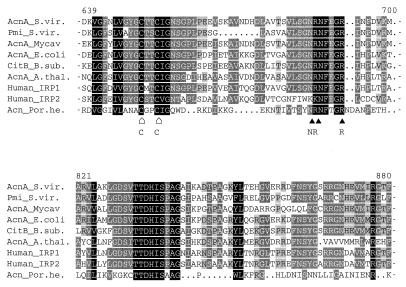

FIG. 2.

Alignment of conserved regions of aconitases and iron regulatory proteins, including AcnA and Pmi from S. viridochromogenes. The regions shown are located in domain 3 (amino acids 639 to 700) and domain 4 (amino acids 821 to 880) of aconitases. Conserved amino acid residues are marked by inverse letters. Corresponding to the structure of the pig heart aconitase (3), ▴ and ⌂, respectively, indicate amino acids and cysteine residues which are structurally conserved and involved in the formation of the 4Fe-4S cluster at the catalytic site. AcnA_S.vir., AcnA from S. viridochromogenes; Pmi_S.vir., phosphinomethylmalate isomerase from S. viridochromogenes; AcnA_Mycav, AcnA from M. avium; AcnA_E.coli; AcnA from E. coli; CitB_B.sub., aconitase CitB from B. subtilis; AcnA_A.thal., AcnA from Arabidopsis thaliana; Human_IRP1, human iron regulatory protein 1; Human_IRP2, human iron regulatory protein 2; Acn_Por.he., porcine heart mitochondrial aconitase.

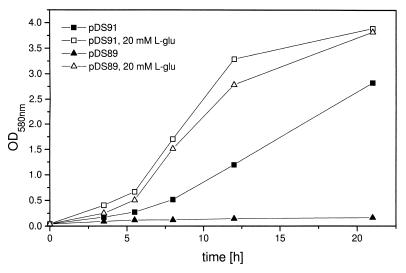

In order to verify the sequence data, an aconitase-deficient E. coli mutant (6) was used for complementation experiments with the acnA gene. The E. coli mutant JRG3259 is characterized by the inactivation of aconitase genes acnA and acnB (6). The mutant is l-glutamate auxotrophic on glucose-containing minimal medium. A 3.4-kb SphI/Acc65I DNA fragment containing the native acnA gene of S. viridochromogenes was subcloned downstream of the lacZ promoter, resulting in plasmid pDS91. E. coli JRG3259 was transformed with pDS91 and pDS89 (expression vector used as a control). A 20-ml volume of M9 minimal medium (14) (with or without 20 mM l-glutamate) in a 100-ml Erlenmeyer flask containing 50 μg of kanamycin ml−1, 15 μg of tetracycline ml−1, and 40 μg of chloramphenicol ml−1 was inoculated with 0.2 ml of an overnight culture of plasmid-carrying strain JRG3259 grown in Luria-Bertani medium. Incubation was performed for 21 h at 37°C and 180 rpm. Induction of the lacZ promoter was done with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). At different times, growth was measured by determination of the optical density at 580 nm. Under aerobic conditions, the S. viridochromogenes acnA gene was able to partially complement the mutant, as indicated by an increase in the growth rate compared to that of the nonsupplemented mutant JRG3259 carrying the expression vector only (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Complementation of aconitase-negative E. coli mutant JRG3259. A culture of JRG3259 with acnA expression plasmid pDS91 was incubated in M9 minimal medium with and without supplementation with l-glutamate (L-glu) for 21 h. As a control, JRG3259 with vector pDS89 was incubated under the same conditions. At different times, growth was measured by determination of the optical density (OD) at 580 nm.

Analysis of the physiological role of AcnA.

In order to examine the function of the AcnA aconitase, the acnA gene was inactivated. Inactivation was carried out with the nonreplicative plasmid pGK1, which carried an acnA gene fragment disrupted by insertion of the aphII gene (Table 1). The transcription of the inserted resistance gene aphII was oriented in the same direction as that of the acnA gene (Fig. 1). E. coli plasmids used for transformation of S. viridochromogenes were isolated from the methylase-negative strain E. coli ET12567 (11). Wild-type S. viridochromogenes was transformed by polyethylene glycol-mediated transformation by using this plasmid as described by Schwartz et al. (15). In Southern hybridization experiments, kanamycin-resistant transformants were identified showing a double-crossover event between the chromosomal copy of the acnA and the mutated fragment of pGK1. In contrast to the wild type, the acnA mutant (ACOA) was not able to develop aerial mycelium and to sporulate on yeast-malt (YM) medium (bald phenotype). The same phenotype was observed for the wild type when the competitive aconitase inhibitor sodium fluoroacetate (0.5% final concentration) was added to the YM medium, indicating that the bald phenotype resulted from the inactivation of acnA. In order to exclude the possibility that the bald phenotype of ACOA is caused by a decreased pH value due to the excretion of organic acids, filter disks soaked with Tris/HCl buffer (0.1 M, pH 8.0) were placed on ACOA mycelium. Thereby, no aerial mycelium formation around the disks was observed. Transformation of ACOA with plasmid pDS92 (Table 1) restored the ability of the mutant to develop aerial mycelium, to sporulate, and to product PTT. The genetic complementation results indicate that the phenotype of the insertion mutation in acnA is not a result of polar effects on genes located downstream.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and phage used in this study

| Strain, phage, or plasmid | Relevant genotype and phenotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| S. viridochromogenes | ||

| Tü494 | PTT-producing wild type | 1 |

| ACOA | Non-PTT-producing; acnA::aphII Kanr | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| ET12567 | F−dam-13::Tn9 dcm-6 hsdM hsdR lacYI | 11 |

| JRG3259 | acnA::KanracnB::Tetr, aconitase negative | 6 |

| Phage λ-ACN2 | λ phage clone carrying acnA gene from S. viridochromogenes | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pEM4 | Streptomyces-E. coli shuttle vector | 13 |

| pIJ486, pIJ487 | pIJ101 derivative; tsr, promoterless aphII gene, promoter probe vector | 21 |

| pSLE39 | pUC21 derivative carrying aphII of transposon Tn5 | 11a |

| pGK1 | pUC18 derivative, 1.6-kb SacI fragment of acnA interrupted by insertion of EcoRV/SmaI fragment of pSLE39 (aphII cassette) into blunt-ended single BbsI site | This study |

| pDS89 | pUC19 derivative; HincII/XmnI fragment of pACYC184 carrying cat gene cloned into SspI site; cat | This study |

| pDS91 | pDS89 derivative carrying acnA-containing 3.4-kb SphI/Acc65I fragment behind lacZ promoter; cat | This study |

| pDS92 | pEM4 derivative carrying acnA-containing 3.4-kb SphI/Acc65I fragment | This study |

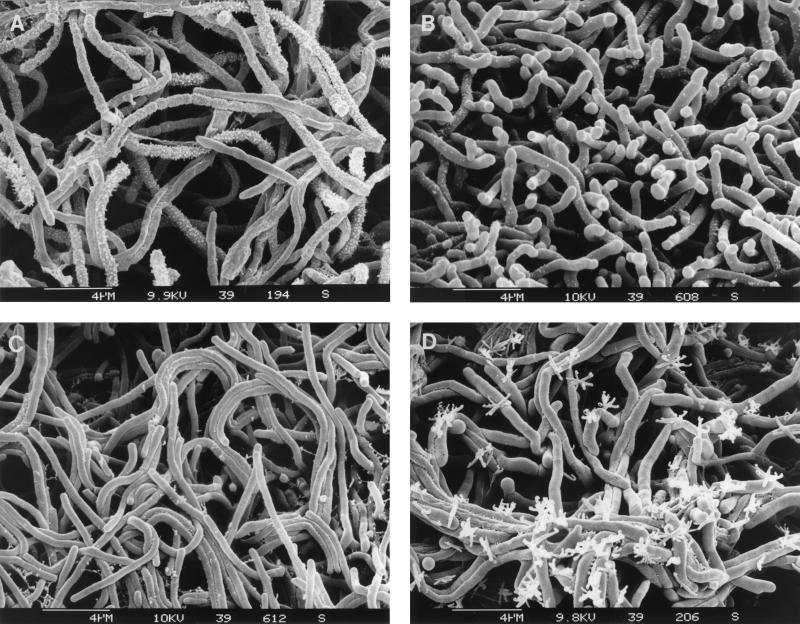

ACOA was also unable to produce the secondary metabolite PTT, suggesting a defect in physiological differentiation. Addition of l-glutamate (5 to 25 mM) to the YM medium partially restored the ability of ACOA to develop white aerial mycelium but not the formation of green spores. The formation of aerial mycelium of the ACOA mutant growing on medium supplemented with l-glutamate was further examined by electron microscopy as described by Tillotson et al. (19). On YM medium without l-glutamate, substrate mycelium with short hyphae was observed (Fig. 4B). Addition of l-glutamate at increasing concentrations resulted in the formation of longer aerial hyphae (Fig. 4C and D), as examined for the wild type (Fig. 4A). The formation of rough spores, characteristic of wild-type S. viridochromogenes (Fig. 4A), was not observed. However, on YM medium with 25 mM l-glutamate, unusual structural elements could be detected at the end of the hyphae, probably representing deformed spores or aerial hyphae (Fig. 4D).

FIG. 4.

Scanning raster electron microscopy of wild-type S. viridochromogenes and the mutant ACOA. Aerial mycelium of wild-type S. viridochromogenes and mutant ACOA grown on YM medium with and without supplementation with l-glutamate for 72 h was examined by raster electron microscopy. Panels: A, wild-type S. viridochromogenes grown on YM; B, ACOA grown on YM medium; C, ACOA grown on YM medium–12.5 mM l-glutamate; D, ACOA grown on YM medium–25 mM l-glutamate.

Not only morphological but also physiological differentiation is affected by supplementation of the mutant with 25 mM l-glutamate, as indicated by the reduced amount of PTT produced (approximately 10% of the wild-type activity).

In other bacteria, the TCA cycle and aconitases also affect morphological differentiation. In B. subtilis, the influence of the TCA cycle, especially of aconitase CitB, on sporulation was examined (2, 7). Inactivation of citB resulted in mutants which were defective in transcription of the expressed earliest sporulation genes (2). The activation of these sporulation genes is dependent on the activated transcription factor Spo0A. In a citB mutant, activation of Spo0A by phosphorylation failed, indicating that the accumulation of citrate or the subsequent lack of TCA intermediates may be responsible for the early sporulation block. It can be speculated that a similar mode of action is the reason for the inhibition of morphological differentiation in S. viridochromogenes.

S. viridochromogenes possesses a second aconitase activity.

Since mutant ACOA was able to grow on glucose minimal medium (12) with 10 g of glucose per liter, a second aconitase may be present in S. viridochromogenes. In order to detect a putative residual aconitase activity, cells of the wild type and mutant ACOA from comparable growth phases (24 to 96 h) were examined for aconitase activity. A 150-ml volume of YM medium in a 500-ml Erlenmeyer flask was inoculated with 1.5 ml of homogenized cells of a 2-day (wild type) or a 5-day (ACOA) preculture and incubated in an orbital shaker (180 rpm) at 30°C. Crude cell extracts were examined for aconitase activity as described by Kennedy et al. (8). Compared to the wild type, a residual aconitase activity of approximately 7% was determined for mutant ACOA (Table 2). The disrupted acnA gene encodes only a truncated AcnA protein missing domain 4, which has been shown to be essential for the function of aconitases (5). Considering the conserved protein structure of aconitases (3, 5), it seems unlikely that the residual activity is caused by this protein. Up to now, it was not known, whether the activity is due to a second aconitase or to an unrelated hydratase-dehydratase having a broad substrate specificity that includes citrate. This protein seems not to be encoded by the aconitase-like gene pmi of the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster, as indicated by the ability of an acnA pmi double mutant to grow on glucose minimal medium (14a).

TABLE 2.

Aconitase specific activity in crude cell extracts of wild-type S. viridochromogenes and acnA mutant ACOA from different growth phases

| Time (h) | Sp act (U/mg of protein)a

|

|

|---|---|---|

| S. viridochromogenes Tü494 (wild type) | S. viridochromogenes ACOA (acnA mutant) | |

| 24 | 0.0960 | 0.0070 |

| 48 | 0.0820 | 0.0041 |

| 72 | 0.0370 | 0.0028 |

| 96 | 0.0170 | 0.0015 |

One unit of enzyme activity could convert 1 nmol of the substrate (trisodium citrate dihydrate)/min (8).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences reported here have been assigned accession no. Y17270 and Y17269 in the EMBL data library. The GenBank accession numbers of the genes used for alignments are X82841, Z99113, X60293, AF002133, and J05224, and the Swiss-Prot numbers are P21399 and P48200.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the DFG (Graduiertenkolleg Mikrobiologie) and by the BMBF (ZSP Bioverfahrenstechnik, D 3.2 E). G. Kienzlen was supported by a grant of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung. Part of this work was financed by a grant of the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie (no. 163607).

We are very grateful to Charles Thompson for communicating results prior to publication and for helpful suggestions, to John R. Guest for providing the E. coli aconitase mutant JRG3259, and to C. F. Bardele and H. Schoeppmann for taking the electron micrographs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bayer E, Gugel K H, Hägele K, Hagenmaier H, Jassipow S, König W A, Zähner H. Stoffwechselprodukte von Mikroorganismen. Phosphinothricin und Phosphinothricyl-Alanyl-Alanin. Helv Chim Acta. 1972;55:224–239. doi: 10.1002/hlca.19720550126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Craig J E, Ford M J, Blaydon D C, Sonenshein A L. A null mutation in the Bacillus subtilis aconitase gene causes a block in Spo0A-phosphate-dependent gene expression. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7351–7359. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.23.7351-7359.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frishman D, Hentze M. Conservation of aconitase residues revealed by multiple sequence analysis. Implications for structure/function relationships. Eur J Biochem. 1996;239:197–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0197u.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grammel N, Schwartz D, Wohlleben W, Keller U. Phosphinothricin-tripeptide synthetases from Streptomyces viridochromogenes. Biochemistry. 1998;37:1596–1603. doi: 10.1021/bi9719410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gruer M J, Artymiuk P J, Guest J R. The aconitase family: three structural variations on a common theme. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:3–6. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(96)10069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gruer M J, Bradbury A J, Guest J R. Construction and properties of aconitase mutants of Escherichia coli. Microbiology. 1997;143:1837–1846. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-6-1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ireton K, Jin S, Grossman A D, Sonenshein A. Krebs cycle function is required for activation of the Spo0A transcription factor in Bacillus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2845–2849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kennedy M C, Emtage M H, Dreyer J-L, Bienert H. The role of iron in the activation-inactivation of aconitase. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:11098–11105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kondo Y, Shomura T, Ogawa Y, Tsuruoka T, Watanabe H, Totsukawa K, Suzuki T, Moriyama C, Yoshida J, Inouye S, Niida T. Studies on a new antibiotic, SF-1293. I. Isolation and physico-chemical and biological characterization of SF-1293 substances. Sci Rep Meiji Seika. 1973;13:34–41. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Labo M, Gusberti L, Rossi E D, Speziale P, Riccardi G. Determination of a 15437 bp nucleotide sequence around the inhA gene of Mycobacterium avium and similarity of the products of putative ORFs. Microbiology. 1998;144:807–814. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-3-807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacNeil D J, Gewain K M, Ruby C L, Dezeny G, Gibbons P H, MacNeil T. Analysis of Streptomyces avermitilis genes required for avermectin biosynthesis utilizing a novel integration vector. Gene. 1992;111:61–68. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90603-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11a.Muth, G. Unpublished data.

- 12.Plaga A. Studien zur mikrobiologischen Produktion von Phosphinothricin aus Streptomyces viridochromogenes Tü494. Ph.D. thesis. Tübingen, Germany: University of Tübingen; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quiros L M, Aguirrezabalaga I, Olano C, Mendez C, Salas J A. Two glycosyltransferases and a glycosidase are involved in oleandomycin modification during its biosynthesis by Streptomyces antibioticus. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:1177–1185. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sambrook J, Fritsch T, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 14a.Schwartz, D. Unpublished data.

- 15.Schwartz D, Alijah R, Nußbaumer B, Pelzer S, Wohlleben W. The peptide synthetase gene phsA from Streptomyces viridochromogenes is not juxtaposed with other genes involved in nonribosomal biosynthesis of peptides. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:570–577. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.2.570-577.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwartz D, Recktenwald J, Pelzer S, Wohlleben W. Isolation and characterization of the PEP-phosphomutase and the phosphonopyruvate decarboxylase genes from the phosphinothricin tripeptide producer Streptomyces viridochromogenes Tü494. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;163:149–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Staden R, McLachlan A D. Codon preference and its use in identifying protein coding regions in large DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1982;10:141–156. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.1.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17a.Thompson, C. J. Personal communication.

- 18.Thompson C J, Seto H. Genetics and biochemistry of antibiotic production. L. C. Vining and C. Stuttard (ed.) Oxford, England: Butterworth Heinemann Biotechnology; 1995. Bialaphos; pp. 197–222. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tillotson R D, Wösten H A B, Richter M, Willey J M. A surface active protein involved in aerial hyphae formation in the filamentous fungus Schizophillum commune restores the capacity of a bald mutant of the filamentous bacterium Streptomyces coelicolor to erect aerial structures. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:595–602. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tomb J F, Whit O, Kerlavage A G, Clayton R A, Sutton G G, Fleischmann R D, Ketchum K A, Klenk H P, Gill S, Dougherty B A, Nelson K, Quackenbush J, Zhou L, Kirknee E F, Peterson S, Loftus B, Richardson D, Dodson R, Khalak H G, Glodek A, McKenny K, Fitzegerald L M, Lee N, Adams M D, Venter J C. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1997;388:539–547. doi: 10.1038/41483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ward J M, Janssen G R, Kieser T, Bibb M J, Buttner M J. Construction and characterization of a series of multi-copy promoter-probe plasmid vectors for Streptomyces using the aminoglycoside phosphotransferase gene from Tn5 as indicator. Mol Gen Genet. 1986;203:468–478. doi: 10.1007/BF00422072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]