Abstract

We cloned and sequenced a 2.7-kb fragment of chromosomal DNA from Clostridium perfringens containing the superoxide dismutase-encoding gene, sod. Previously, rubrerythrin from C. perfringens had been isolated and its gene (rbr) had been cloned (Y. Lehmann, L. Meile, and M. Teuber, J. Bacteriol. 178:7152–7158, 1996). Northern blot experiments revealed a length of approximately 800 bases for each transcript of rbr and sod of C. perfringens. Thus, rbr and sod each represent a monocistronic operon. Their transcription start points were located by primer extension analyses. sod transcription was shown to depend on the growth phase, and it reached a maximum during the transition from log phase to stationary phase. Neither sod nor rbr transcription was influenced by oxidative stress.

The discovery of superoxide dismutase (SOD) (EC 1.15.1.1) activities in obligate anaerobic organisms has raised the question of whether SODs play the classical role of superoxide radical scavengers during the short exposure of these anaerobes to oxidating environments or another role which has not yet been defined (20). Various attempts to isolate the appropriate sod genes from SOD-positive anaerobes have failed due to the fact that the activity-staining assays are not specific for classical SODs. But such attempts have led to detection of the rubredoxin oxidoreductase gene, rbo, from Desulfovibrio vulgaris (15) and of the rubrerythrin gene, rbr, from Clostridium perfringens (9). Both gene products were shown to functionally complement Escherichia coli sodA sodB mutants lacking cytosolic SODs, but their physiological function is unknown. Recently, in vitro NADH oxidation by rubrerythrin was described (5), and it has been suggested that rubrerythrin is part of an oxidative stress response (9, 10).

The identification of complete sod gene sequences from strict anaerobes such as Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum (11), Porphyromonas gingivalis (13), and Bacteroides fragilis (EMBL M96560) and a partial sod-like sequence from C. perfringens (16) has opened the field to exploration of the function of SOD in obligate anaerobes. To date, however, no studies of the transcription of sod from anaerobes have been published. The present study describes the isolation of a complete sod gene from the strict anaerobe C. perfringens and mRNA analyses of both rbr and sod transcripts in different stages of growth and under oxidative stress conditions.

Cloning and sequencing of the sod gene region from C. perfringens.

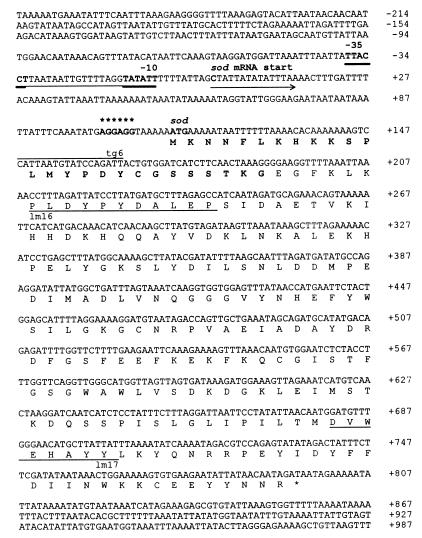

In order to clone the complete sod gene from C. perfringens NCIMB8875 (National Collection of Industrial and Marine Bacteria, Aberdeen, Scotland), a fragment from its genome was amplified by PCR with the primer pair lm16 (5′-CCITAYICITAYGAYGCIYTIGARCC-3′) and lm17 (5′-RTARTAIGCRTGYTCCCAIACRTC-3′). This fragment was used as a probe in Southern blots of C. perfringens chromosomal DNA for cloning and sequencing fragments of 2.7 kb of total length. The deduced amino sequence of a 684-bp open reading frame extending from nucleotides 114 to 798 (Fig. 1) showed extensive homology to amino acid sequences typically conserved in Mn-SODs (54.0% identity to Mn-SOD from Bacillus subtilis [8], 51.2% identity to Mn-SOD from Listeria monocytogenes [1], and 44.0% identity to Mn-SOD from E. coli [19]). Therefore, the coding region of this polypeptide was designated sod. The gene is preceded by a perfect ribosome binding site containing a box of 7 nucleotides complementary to the 3′ end of the 16S rRNA of C. perfringens (Fig. 1). However, the 227-amino-acid sequence encoded by sod is longer than that of other bacterial and archaeal Mn- and Fe-SODs. Sequence alignment with these organisms revealed that the N terminus of the C. perfringens SOD is extended by 26 amino acids, which is a structural feature postulated so far only for an Acinetobacter SOD (6). Finally, the gene was transformed into E. coli QC774 (2), which resulted in high SOD activity and functional complementation of this sodA sodB mutant (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Nucleotide sequence of the sod gene of C. perfringens and the predicted amino acid sequence of the encoded SOD and the sod promoter region. The underlined amino acids are highly conserved among SODs and indicate the regions from which oligonucleotides lm16 and lm17 were derived. The overlined nucleotide sequence indicates the complementary sequence of the primer (tg6) used for primer extension analysis. A potential ribosome binding site is marked by asterisks. The consensus promoter sequences (−35 and −10) are in underlined boldface, and the transcription start point is marked by an arrow. Boldface amino acids indicate the N terminus, which is unusually expanded compared to other Mn- and Fe-SODs.

Transcriptional analysis of the sod and rbr genes.

For all mRNA analysis experiments, C. perfringens was cultivated in brain heart infusion broth (Oxoid) containing 0.05% (wt/vol) cysteine hydrochloride and 0.1% resazurine (pH 7.2) at 37°C. The medium was prepared in an anaerobic hood (Coy Laboratory Products, Ann Arbor, Mich.) under an atmosphere of nitrogen containing 6% hydrogen. If required, a partially aerobic environment was achieved by adding both 0.5% (vol/vol) oxygen and 0.1 mM paraquat (methylviologen) to serum flasks when cultures reached an extinction coefficient of 0.18 to 0.2 at 600 nm, as previously described (9). If not otherwise indicated, standard procedures were used for all experiments (18). For each experiment, 30 μg of total RNA, isolated by a hot acid-phenol method, was used (14). In Northern blot experiments, guanidine thiocyanate was used as an alternative denaturant in place of formaldehyde (7). The probes used for Northern analysis and slot blots consisted of an internal fragment of the sod or rbr gene and were labeled with [α-32P]dATP by the random priming method. Membranes were hybridized either in a strong sodium dodecyl sulfate buffer (3) at 65°C or in the presence of 50% formamide at 42°C. Primer extension experiments were carried out with the [γ-32P]ATP end-labeled oligonucleotide tg6 (5′-AATCTGGATACATTAATG-3′ [Fig. 1]) or Rub5 (5′-AGATTTTCAGCAGTTTTA-3′ [see Fig. 4]).

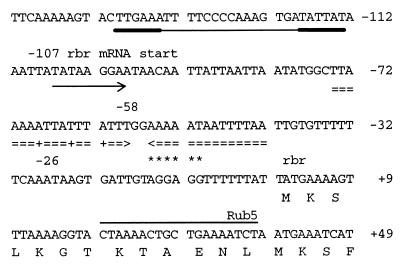

FIG. 4.

Nucleotide sequence of the rbr promoter region from C. perfringens (9). The overlined nucleotide sequence indicates the complementary sequence of the primer used for primer extension analysis. A potential ribosome binding site is marked by asterisks. Possible consensus promoter sequences are bold underlined, and the transcription start point is marked by an arrow. A predicted stem-loop structure that might have resulted in a preferred processing site at position −58 is double underlined (+, possible bulges).

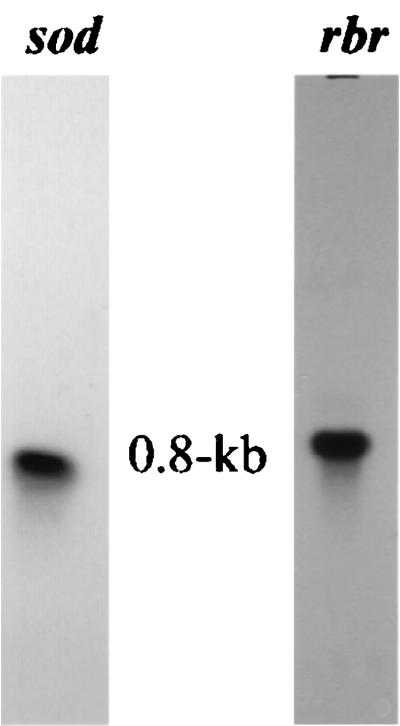

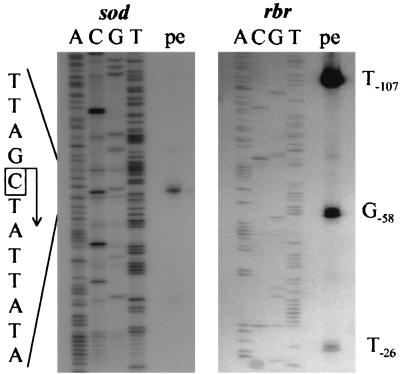

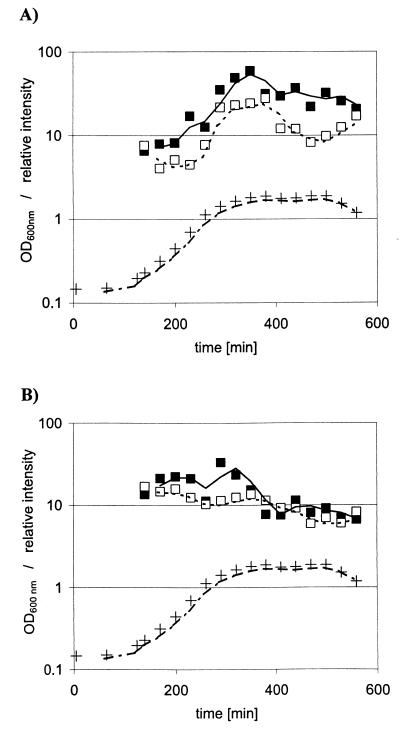

sod and rbr Northern hybridizations each revealed a single sharp signal corresponding to mRNA transcripts of approximately 800 nucleotides (Fig. 2). Thus, the sod and rbr genes are transcribed in C. perfringens as monocistronic operons. This is in contrast to the rbr gene from D. vulgaris, where rbr is cotranscribed with genes encoding a Fur-like and a rubredoxin-like protein (10). The transcription start point of the sod gene was then located by primer extension analysis 113 nucleotides upstream of the translational initiation codon. No other apparent transcriptional start sites were detected (Fig. 3). A good −10 promoter sequence (TATATT) is evident upstream of the transcriptional start site and a moderate, −35 promoter (TTACCT) was found 16 bases farther upstream (Fig. 1). In repeatable primer extension experiments of the rbr gene, three major signals were always detected (Fig. 3) independently of growth phase (mRNA from log and stationary phases was analyzed). The most probable transcription start point was found 107 nucleotides upstream of the initiation codon. Next to this site, consensus promoter sequences (TATTAT and TTGAAA) were found (Fig. 4). The other signals, at positions −58 and −26, were weaker, and their upstream regions had only low similarity to consensus promoter sequences; thus, they might represent degradation products. In particular, the strong signal at −58 corresponds to a G in the loop of a predicted large stem-loop structure (Fig. 4). RNA slot blots were done with total RNA isolated from anaerobically grown and oxidatively stressed cells. Total RNA was isolated every 30 min during exponential- and stationary-phase growth, the RNA concentration was equilibrated, and slot blots were done with five different dilutions (10, 5, 1, 0.5, and 0.1 μg). The same membranes were subsequently hybridized with sod or rbr probes, and 16S rRNA was hybridized as a control. Spot densities of the radiograms were measured with a digital imaging system (AlphaImager; Alpha Innotech Corp., San Leandro, Calif.). C. perfringens cultures stressed by both oxygen and paraquat had the same growth rate as the anaerobically inoculated cells, but their morphology changed from normal 5-μm-long rods to up to 100-μm-long threads (data not shown). Mn-SODs are part of the defense mechanism against reactive oxygen species. It was expected that oxidative stress would result in an induction of sod transcription, as is reported for sodA genes from gram-negative bacteria (21). However, a slight decrease in sod transcription was measured (Fig. 5A). The negative shift was only about twofold, and since experimental inaccuracy might be present, this negative shift was not considered significant. No inducible effect of paraquat on Mn-SOD activity in B. subtilis was measured either (8). Furthermore, induction of the Mn-SOD of Staphylococcus aureus occurred specifically during the postexponential growth phase (4). These results led to the conclusion that in gram-positive bacteria the regulation of SOD is substantially different than the well known SoxRS regulation mechanism of sodA in E. coli. Indeed, the sod mRNA level of C. perfringens increased during exponential growth and reached a maximum at the entry into stationary phase, independently of whether C. perfringens was grown under anaerobic or partially aerobic conditions (Fig. 5A). The sod transcript was 10-fold higher and decreased during stationary phase but remained still more than 5-fold higher than during exponential growth. This observation is consistent with the increased levels of Mn-SOD during stationary phase reported for other bacteria, such as B. subtilis (8), S. aureus (4), and E. coli (12), or for other enzymes of the defense mechanism against reactive oxygen species, such as catalase (12, 17). Interestingly, rubrerythrin transcription was influenced neither by oxidative stress nor by growth phase, and the rbr mRNA level decreased only slightly during growth (Fig. 5B). These results did not lead to any conclusions about the role of rubrerythrin in the defense system against oxygen in C. perfringens.

FIG. 2.

Northern blot analysis of the C. perfringens sod and rbr genes. sod and rbr represent monocistronic operons of approximately 800 nucleotides each.

FIG. 3.

Mapping of the 5′ ends of the sod and rbr transcripts of C. perfringens by primer extension analysis. Primer extension products (pe) are shown to the right of the corresponding sequencing ladder on a 6% (wt/vol) sequencing gel. The transcription start point is boxed for the sod operon (left), and three potential start points are numbered for the rbr operon (right). The numbers assigned to the nucleotides correspond to the numbering of the nucleotides in Fig. 4.

FIG. 5.

sod (A) and rbr (B) transcripts during log and stationary phases of C. perfringens grown under anaerobic (■) or partially aerobic (□) conditions. Relative intensities were determined by densitometry analysis. Growth was followed by spectrophotometry at 600 nm (+). OD, optical density.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of the C. perfringens NCIMB8875 sod gene has been submitted to the EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ databases under accession no. Y10531.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant 0-20-219-96 from ETH Zürich.

We thank D. Touati for providing E. coli strains.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brehm K, Haas A, Goebel W, Kreft J. A gene encoding a superoxide dismutase of the facultative intracellular bacterium Listeria monocytogenes. Gene. 1992;118:121–125. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90258-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carlioz A, Touati D. Isolation of superoxide dismutase mutants in Escherichia coli: is superoxide dismutase necessary for aerobic life? EMBO J. 1986;5:623–630. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04256.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Church G M, Gilbert W. Genomic sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:1991–1995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.7.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clements M O, Watson S P, Foster S J. Characterization of the major superoxide dismutase of Staphylococcus aureus and its role in starvation survival, stress resistance, and pathogenicity. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3898–3903. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.13.3898-3903.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coulter E D, Shenvi N V, Kurtz D M. NADH peroxidase activity of rubrerythrin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;255:317–323. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geissdörfer W, Ratajczak A, Hillen W. Nucleotide sequence of a putative periplasmic Mn superoxide dismutase from Acinetobacter calcoaceticus ADP1. Gene. 1997;186:305–308. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00728-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goda S K, Minton N P. A simple procedure for gel electrophoresis and Northern blotting of RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:3357–3358. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.16.3357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inaoka T, Matsumura Y, Tsuchido T. Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequence of the superoxide dismutase gene and characterization of its product from Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3697–3703. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.14.3697-3703.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lehmann Y, Meile L, Teuber M. Rubrerythrin from Clostridium perfringens: cloning of the gene, purification of the protein, and characterization of its superoxide dismutase function. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:7152–7158. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.24.7152-7158.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lumppio H L, Shenvi N V, Garg R P, Summers A O, Kurtz D M. A rubrerythrin operon and nigerythrin gene in Desulfovibrio vulgaris (Hildenborough) J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4607–4615. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.14.4607-4615.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meile L, Fischer K, Leisinger T. Characterization of the superoxide dismutase gene and its upstream region from Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum Marburg. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;128:247–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Michán C, Manchado M, Dorado G, Pueyo C. In vivo transcription of the Escherichia coli oxyR regulon as a function of growth phase and in response to oxidative stress. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2759–2764. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.9.2759-2764.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakayama K. The superoxide dismutase-encoding gene of the obligately anaerobic bacterium Bacteroides gingivalis. Gene. 1990;96:149–150. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90357-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oelmueller U, Krueger N, Steinbuechel A, Friedrich C G. Isolation of prokaryotic RNA and detection of specific messenger RNA with biotinylated probes. J Microbiol Methods. 1990;11:73–81. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pianzzola M J, Soubes M, Touati D. Overproduction of the rbo gene product from Desulfovibrio species suppresses all deleterious effects of lack of superoxide dismutase in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6736–6742. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.23.6736-6742.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poyart C, Berche P, Trieu-Cuot P. Characterization of superoxide dismutase genes from Gram-positive bacteria by polymerase chain reaction using degenerate primers. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;131:41–45. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(95)00232-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rocha E R, Smith C J. Regulation of Bacteroides fragilis katB mRNA by oxidative stress and carbon limitation. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7033–7039. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.22.7033-7039.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takeda Y, Avila H. Structure and gene expression of the Escherichia coli Mn-superoxide dismutase gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:4577–4589. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.11.4577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Touati D. Superoxide dismutases in bacteria and pathogen protists. In: Scandalios J G, editor. Oxidative stress and the molecular biology of antioxidant defenses. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1997. pp. 447–493. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Touati D. Transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation of manganese superoxide dismutase biosynthesis in Escherichia coli, studied with operon and protein fusions. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:2511–2520. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.6.2511-2520.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]