ABSTRACT

This study attempted to discuss the historical context and current practice of forensic medicine in South Asia. Comparisons within and between countries in South Asia, and between South Asia and the developed countries (represented by Japan and the USA) have been made to provide an insight into their distinct practice of forensic medicine. Though the formal establishment of forensic medicine in South Asia commenced at a comparable period to the developed countries, their pace of development has been considerably slow. Moreover, their ways of practice as well have evolved differently. In effect, South Asian countries follow an ‘integrated service’ system, whilst Japan and the USA practice ‘divided service’ systems to provide forensic medical services. Similarly, regarding the death investigations, most South Asian countries follow a Police-led death investigation system, whereas Japan and the USA follow a hybrid model and the Medical examiner’s system of death investigation, respectively. Indeed, forensic medicine in South Asia is undeniably underdeveloped. In this paper, by highlighting the issues and challenges confronted in South Asia, key actions for prompt redressal are discussed to improve the standard of forensic medical services in South Asia.

Keywords: death investigation system, forensic medicine, medicolegal system, South Asia

Forensic medicine is a subspecialty of medicine that utilizes medical knowledge to address legal issues. Its origin and development in the history of the medical profession can be traced back to ancient times. The roles and applications of forensic medicine have as well evolved and expanded over time.1, 2 Apart from the criminal and civil justice system, it is also applied in public health and social welfare programs today. However, the practice is not uniform worldwide. Indeed, the scope and the methods of practice largely depend on the existing legal system and healthcare approaches available in the country. Likewise, the availability of resources, priorities in developmental policies, and religious and cultural sentiments prevailing in the region, and or/country affect the pace of its development.3,4,5 On the other hand, the historical context of the practice might be significant in shaping the type of medicolegal system one country adopts. This is particularly true in the case of South Asia, where many countries once ruled by the British Empire, the English laws transplanted across them played a significant role in defining the medicolegal models.6 Furthermore, unlike other mainstream branches of clinical medicine, partly due to the reasons stated above, the practice of forensic medicine is often hard to standardize and subject to quality controls.1 Nevertheless, a poor medicolegal service carries far worse consequences.

South Asia is home to a fifth of the world’s population. The countries include Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka, which share deep cultural and geopolitical history. Moreover, many commonalities endure across them in developmental philosophies, healthcare approaches, and social goals. However, the region is faced with great socioeconomic inequalities creating huge gaps in access to healthcare.7 Additionally, it is a region with protracted conflicts. Conflicts within and between countries have resulted in considerable civilian deaths, injuries, and sexual abuses.8 Also, South Asia is prone to various natural disasters such as earthquakes, tsunamis, floods, etc., which demand responsive and dynamic healthcare systems.9 Fair access and provision to quality healthcare including forensic medical services in South Asia have recently become a topic of much discussion.7, 10, 11

In this paper, we discuss the practice of forensic medicine in South Asia. We are concerned with provisions of quality medico-legal services in the region, and our study will offer valuable insights into the current status quo of the same. We start by discussing the historical evolution of forensic medicine in the region and then examine its attributes typical to the region. Specifically, we look at what modes of practice are prevalent, and what dominant form of death investigation systems are being practiced in South Asia. The review makes comparisons within and between the South Asian countries. We also attempt to compare the practice of forensic medicine in South Asia among developed countries, represented by Japan and the United States of America (USA), to provide an understanding of their distinctiveness. In moving forward, issues and challenges faced by South Asian countries are highlighted and priorities for future actions are suggested. This study is based on the personal experiences of the authors and a scoping review of grey and available literature in the research databases (PubMed and Google Scholar).

ORIGIN AND DEVELOPMENT OF FORENSIC MEDICINE IN SOUTH ASIA

In this section, we briefly discuss the origin and development of forensic medicine in South Asia by highlighting remarkable events that have taken place in the context of its formal establishments.

British came to India in the 17th century and established the East India company. It was followed by the introduction of the British judiciary system in 1639, and the establishment of the first hospital in Chennai in 1664, respectively. The first recorded medicolegal autopsy was conducted by Dr. Edward Bulkley in August of 1693 at Chennai hospital, who later went on to be appointed as the Coroner in 1697. With the establishment of medical colleges (Calcutta medical school in 1822; Madras medical college in 1835), the creation of separate departments for medical jurisprudence ensued. Between 1909 and 1915, 1019 postmortem autopsies were performed in one of the government medical hospitals, in Madras alone.6

Bangladesh, once a part of British India also inherited the British medicolegal system. Between 1747 and 1947, usually referred to as the British period, the civil surgeons in the district provided all the medicolegal services under their jurisdictions. This system continued till the country gained its independence in 1971 from Pakistan. However, academic departments of medical Jurisprudences were established in several of the medical colleges during this period, and those civil surgeons were employed as part-time lecturers. After 1971, reorganizations in the departments were conducted by creating professional posts in newly named Forensic Medicine Departments in medical colleges across Bangladesh.12

Pakistan’s judiciary system is said to have evolved through three eras the ‘Hindu period’, the ‘Muslim Period’, and the ‘British colonial period.’ Before 1979, Pakistan followed the British medicolegal system, in which the Police investigated all the bodily crimes. Medical doctors’ role was limited to assisting the police in criminal death investigations. However, post-1979, significant changes were made in the criminal justice system by enacting and enforcing numerous ordinances. The notable ones are the Hudood ordinance, Qisas, and Diyat ordinances of 1990. These laws incorporated clauses related to bodily harm and sexual offenses from the Islamic perspective. Moreover, these new legislations provided provisions for appointing medical doctors for forensic medicine services across healthcare centers in Pakistan.13, 14

Sri Lanka, an island nation in the Indian subcontinent, gained its independence from the British in 1948. It was ruled by the Portuguese and Dutch between 1505-1815, and later by the British from 1815 to 1948. Expectedly, its legal system also underwent several transformations during those phases. The current legal system of Sri Lanka contains both elements of Roman-Dutch law and English law. The first modern hospital was built in Colombo in 1819 and was constantly upgraded since then. The hospital was also equipped with a mortuary. In 1870, the Colombo Medical school was established, which started giving lectures to students on forensic medicine. The formal death inquiry procedure in Sri Lanka was set up sometime in 1883, adapting from the British medicolegal system. As the hospitals and medical doctors increased in numbers, medicolegal services including autopsy were provided in most district hospitals. By 1935, the first qualified Sri Lankan medicolegal expert started rendering specialist forensic medicine services in Colombo.15, 16

The earliest written law for Nepal was enacted in 1854. It was based on Britain and continental Europe’s legal system. In it, the religious components of the Hindu principles were engrained. In 1951, as the country became a democratic republic from the monarchy systems, the written law underwent significant reforms. One notable change was evident in the systematization of the medicolegal services in Nepal. Autopsies for medicolegal reasons started only in the 1960s, with jail doctors, also referred to as Police surgeons appointed among the medical doctors started performing autopsies at Bir Hospital, Kathmandu, Nepal. A similar system was introduced at other hospitals where government-appointed medical doctors rendered medicolegal services including autopsy.17

The Forensic Medicine Directorate in Afghanistan was established in the year 1981 under the Ministry of Public Health. It looks after the forensic medicine services, forensic laboratory services, and medical malpractices of medical professionals in the country. The forensic medicine directorate office is in Kabul city, and it also has service provisions at the central level. At the provincial level, forensic medicine units provide the services. Besides the local law enforcement authorities (Police, attorneys and local courts), many national and international organizations working on humanitarian affairs have been equally benefiting from forensic medicine services in Afghanistan ever since.18

Bhutan is a small Himalayan kingdom in South Asia. The country has an area of 38,394 sq. km, placing 137th in size globally.19 Of about 0.73 million population, three-fourths are Buddhist, and the country’s culture and etiquette are influenced by Buddhism. As early as the eighth century, and through to the early 19th century, traditional healing practices were prevalent in Bhutan. However, the establishment of the first dispensary of western medicine in 1920, marked the start of the modern healthcare system in the country.20, 21 Not much is known about the past practice of forensic medicine in Bhutanese history. Anecdotal reports are ambiguous, and contradictory both in their practice and significance in traditional Bhutan. Until 1980, when a crime against a human body was reported, village heads probed minor cases whereas district officials investigated the serious ones including homicides. These medicolegal duties were performed by non-medical personnel without seeking medical opinions. Bhutan’s Police force was instituted in 1965 and the first comprehensive ‘Police Act’ was drafted in 1980. It was rescinded and replaced by the ‘Royal Bhutan Police Act’ in 2009.22, 23 Section 93 of the latter Act provides Investigating Police Officer (IPO) to call upon the medical doctors to provide their assistance in investigating crimes against the human body. Based on this medicolegal framework, medical doctors in Bhutan render forensic medicine services at their healthcare centers today. Jigme Dorji Wangchuk National Referral Hospital (JDWNRH), the largest in the country with the most specialist services available was established in 1954. In the year 2005, the first Bhutanese forensic medicine specialist doctor trained overseas returned to Bhutan and created the Department of Forensic Medicine and Toxicology at JDWNRH.24 Since then, the department has been actively involved in improving the country’s medicolegal system and forensic medicine services by providing training and consultative services to medical doctors and relevant stakeholders across the country.

Table 1 shows the historical landmarks related to the evolution of forensic medicine, types of forensic medical service systems, and principal forms of death investigation systems present in South Asia, Japan, and the USA.

Table 1. Historical landmarks, types of Forensic medical services, and death investigation systems present in South Asia, Japan and USA.

| Countries | Historical events related to evolution ofForensic Medicine in South Asia | Type of forensic medical service system | Death investigation systems |

| Afghanistan18 | ∙ Directorate of Forensic Medicine established in 1981 | Integrated service | ∙ Police, Magistrate, and family can request an autopsy |

| Bangladesh12 | ∙ Followed British medicolegal system between 1747 & 1947∙ Several medical jurisprudences created from 1947-to 1971∙ Medical jurisprudence renamed to Forensic Medicine Department & professional posts created post-1971 |

Integrated service | ∙ Police-based death investigation system |

| Bhutan24 | ∙ Modern healthcare introduced in 1920∙ Department of Forensic Medicine & Toxicology created at JDWNRH in 2005 |

Integrated service | ∙ Police-based death investigation system∙ A team of Police, Medical doctors, and local court officials conduct inquest for custodial deaths |

| India6, 27 | ∙ First medicolegal autopsy conducted in 1693 in Chennai∙ Medical jurisprudence departments created in medical schools (Calcutta medical school in 1822; Madras medical college in 1835) | Integrated service | ∙ Police inquest system for criminal deaths∙ Magistrate for custodial and maternal deaths |

| Nepal17, 25 | ∙ Systemization of medicolegal services by statutes in 1951∙ Medicolegal autopsy started in the 1960s | Integrated service | ∙ Police inquest system for criminal deaths∙ District chief officer investigates custodial deaths |

| Pakistan13, 14 | ∙ Before 1979- British medicolegal system was practiced∙ Post-1979 numerous laws were enacted favoring greater participation of medical doctors in matters related to forensic medicine |

Integrated service | ∙ Police-based death investigation |

| Sri Lanka15, 16 | ∙ First hospital established in Colombo in 1870∙ Colombo Medical school was founded in 1870 & lectures on medical jurisprudence started∙ Proper death investigation system based on Coroner system established in 1883∙ First native forensic medicine expert graduated and started working in Colombo in 1935 |

Integrated service | ∙ Magistrate investigates criminal deaths∙ Coroner and Inquirer into sudden deaths investigate sudden and unexpected deaths |

| Japan28, 29 | ∙ Death inspection system existed as early as 1737 in Japan∙ Department of Forensic Medicine at Tokyo Imperial University established in 1888∙ Judicial autopsy started in 1890 |

Divided service | ∙ Hybrid model of Police and Medical Examiner’s system∙ Judicial autopsy is always performed in Forensic Medicine Departments∙ ME’s office conducts administrative and consent autopsies |

| USA31, 32 | ∙ Coroner system introduced in 1635 by British colonial rule∙ First medicolegal autopsy conducted in 1665 in Maryland, USA∙ Introduced ME system in 1877 & by 1900s, most Coroner systems replaced by ME |

Divided service | ∙ Medical Examiner’s system |

MODE OF PRACTICE AND RELATED SERVICE FUNCTIONS

As mentioned elsewhere, the practice of forensic medicine differs worldwide, with numerous factors influencing it. One fundamental difference that exists in the systems can be explained in terms of how forensic medical practitioners render forensic medicine services. Putri et al. classified the systems into two categories, namely “integrated service” and “divided service” systems.1 In the former type, the forensic medical practitioner performs both clinical forensic medicine and forensic pathology-related duties simultaneously. On the other hand, in the “divided service” system, clinical forensic medicine and forensic pathology services are handled by different forensic medical practitioners.

South Asia, a region interlinked in many aspects, yet having had the influence of foreign powers in the recent past, inherited or represents similar forensic medicine practices. That is, most South Asian countries practice clinical forensic medicine and forensic pathology together using the ‘integrated service’ system. The forensic medical practitioner renders both services from designated government healthcare centers and dedicated forensic institutions. The Ministry of Health/Public health department of the respective country is directly concerned with the governing and management of human resources and infrastructure needed for efficient service delivery. Various healthcare facilities ranging from the university teaching hospitals and central forensic institutes to the primary healthcare centers are involved in the service provision. As different level of healthcare centers is involved, the availability and quality of forensic medical services differ within the country in South Asia. For example, at the higher centers and university teaching hospitals, the service providers are usually forensic medicine experts with higher academic qualifications. Whilst the general medical doctors render forensic medical services at the district hospitals and primary healthcare centers. This also translates to services often being limited and substandard, as the forensic units at peripheries lack basic kits or mortuary to perform forensic investigations compared to higher centers.9, 13, 17, 25, 26

Most countries in South Asia have designated government medical officers appointed at hierarchical levels of healthcare facilities (Central level, provincial hospitals, district hospitals, and primary healthcare centers) to offer forensic medical services. Furthermore, Pakistan has a legal requirement set in appointing medicolegal officers: A minimum of two years must have been served as a medical doctor since graduation to be appointed as a medicolegal officer, for example.14 On the other hand, it is not the case in Sri Lanka and Nepal, any junior medical officer with no added training or experience in the forensic field could be appointed by the government for the role.25, 26 In Bhutan’s case, there are only two practicing forensic medicine experts in the country who are placed in the Department of Forensic and Toxicology at JDWNRH. Forensic medical services at other healthcare centers are provided by the general medical doctors posted for routine clinical duties. Irrespective of their qualifications and experiences, they are challenged to render the forensic medical services once posted. The only forensic medicine-related lectures and exposure to field works they have is from their undergraduate medical training. Consultations and helps from the forensic medicine experts at JDWNRH are rendered to them, nonetheless.

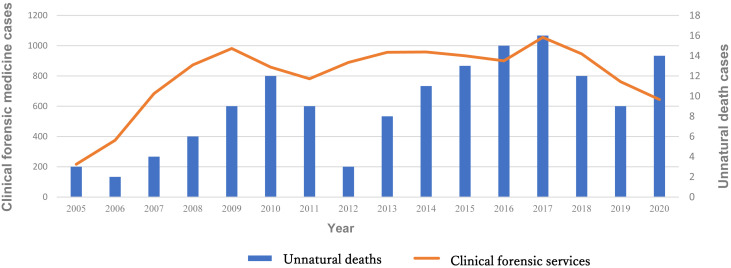

Forensic medical services in South Asia include (not limited to) examinations of victims from physical/sexual assaults/rape, accidental injuries, child abuse, elderly abuse, torture in prisons, forensic age estimation in children, examination of drunk drivers/crime perpetrators, embalming, unnatural death investigations and as an expert witness in courts. Depending on how advanced the forensic medicine department/unit is, it also caters to other forensically important services, like serving as one-stop crisis centers for the victims of domestic violence, providing first aid care and relevant counseling, etc. However, services related to clinical forensic medicine constitute major workloads in most forensic departments/units in South Asia. Figure 1 shows the medicolegal cases handled by the Department of Forensic Medicine and Toxicology at JDWNRH in Bhutan between 2005 and 2020.

Fig. 1.

Medicolegal services provided by the Department of Forensic and Toxicology at JDWNRH, Bhutan from 2005 to 2020. Clinical forensic medicine services include examination of victims/perpetrators of physical/sexual assaults, rape, etc. Embalming and postmortem external body examinations constitute forensic pathology services. Source: Department of Forensic and Toxicology, JDWNRH. JDWNRH, Jigme Dorji Wangchuk National Referral Hospital.

FORENSIC DEATH INVESTIGATION SYSTEMS IN SOUTH ASIA

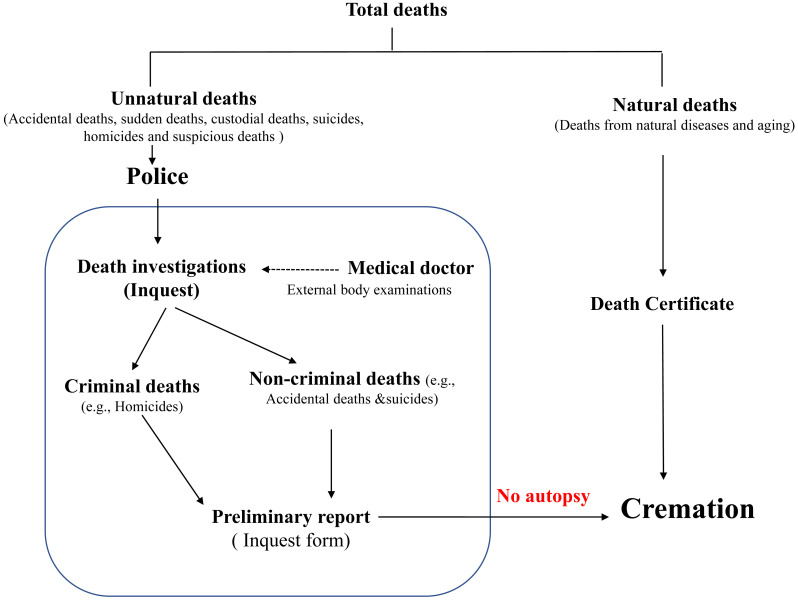

Bangladesh, Bhutan, Nepal, India, and Pakistan today have a Police-based death investigation system.12, 13, 25, 27 Though the Coroner’s system which was transplanted by British India once existed in these countries, it has been replaced and modified to suit the changes in legal systems and healthcare approaches over the decades. In these five countries, all unnatural death or that looks suspicious should be notified to the Police first. ‘Unnatural death’ largely constitutes accidental deaths, sudden deaths, custodial deaths, suicides, homicides, and suspicious deaths. The decision to probe further by performing an autopsy is made by the Police. The Police prepare an inquest report, and the body is released to the relatives if no foul play is suspected. If there is a suspicion of criminality, the body will be sent for autopsy at the nearby hospital. The IPO might also request a medical doctor to visit the scene of death to facilitate the investigation, but it is often rare. In special circumstances, for example, deaths in prison, a team of experts is formed to conduct an inquest. A team may comprise Police, a medical doctor, and an official from a local court, as in the case of Bhutan. Custodial deaths in Nepal are investigated by the Chief district officer whereas, in India, a Magistrate performs the inquest for the same. Medicolegal autopsies are performed by medical doctors with diverse qualification backgrounds and professional positions. However, it depends on the location and their availabilities across healthcare centers. In Nepal, doctors working in private sectors who have required training and qualifications may also be authorized to perform autopsies.25 In Bangladesh, in areas where medical colleges are available, the academic staff and postgraduate trainees perform autopsies, in other areas, the civil surgeons/ district health administrator in the district hospitals perform autopsies.12 The Police as the lead investigator play a decisive role in the police-led death investigation system. It is, however, to be noted that in Bhutan’s case, medical doctors are equally involved in the process right from the beginning and can be the sole service provider in the death investigation process. Moreover, death scene visit is a routine practice in Bhutan. Sadly, the country does not have any mortuaries with autopsy facilities, and as such, postmortem examination is limited to external body examinations in Bhutan. Figure 2 shows the current death investigation system of Bhutan.

Fig. 2.

Death investigation system of Bhutan. When unnatural deaths (Accidental deaths, sudden deaths, custodial deaths, suicides, homicides and suspicious deaths) are reported to the Police, a death investigation (Inquest) is initiated. A medical doctor performs external body examinations and assists the Police in determining the medical cause of death. In doing so, two types of deaths are determined: Criminal and non-criminal deaths. A preliminary report is compiled in an ‘Inquest form’ after which the body is released for cremation. No full-body autopsy is performed in Bhutan.

In Sri Lanka’s context, three distinct death investigative bodies exist, i.e., the ‘Magistrate’, ‘Coroner’, and ‘Inquirer into sudden deaths (ISD).’ Homicides, suspicious deaths, custodial deaths, and deaths resulting from criminal negligence are probed by the Magistrate. Coroners and ISD examine sudden and unexpected deaths, which are non-criminal. The Coroner system operates in large cities, whilst at the peripheries, ISD performs the above task. The Ministry of Justice appoints them (Coroner and ISD) from non-medical backgrounds and is dependent on the medical doctors in probing the medical cause of deaths. However, they still have the power to order medicolegal autopsies if the situation arises. The Coroner’s system in Sri Lanka, which is still practiced is said to be the remnants of the British medicolegal system.16

Like in Bhutan, autopsies are not performed as a routine practice in Afghanistan. In principle, three types of legal authorities can order an autopsy: Police, Prosecutor, and the family of the deceased. Each provincial hospital has a medicolegal doctor posted to render forensic medicine services including autopsy, but in practicality, it is hardly performed. This could be due to a lack of training and amenities available at their disposal. Moreover, the social stigma for forensic doctors exists in Afghanistan.18

FORENSIC MEDICINE IN JAPAN

Records show that the death inspection system in Japan existed as early as 1736, even during the times of the Samurai administration. With the establishment of the Department of Forensic Medicine at Tokyo Imperial University in 1888, academic lectures on forensic medicine were started. In 1890, the government of Japan introduced the Crime procedure law stipulating the provision of a judicial autopsy system. Before the second world war, the Japanese legal system had the influence of German law. However, after the second world war, the American laws were introduced in Japan which brought changes to the practice of forensic medicine as well.28

Japan follows a ‘divided service system’ in its practice of forensic medicine. A forensic pathologist and medical examiner are concerned with forensic pathology services, whilst the clinicians render clinical forensic medical services. Forensic pathologists are usually attached to the departments of forensic medicine in medical universities. They give lectures on forensic medicines to students and perform autopsies when the police ask them to. The medical examiner could be any licensed medical doctor who undergoes additional training and is allowed to investigate the deaths including autopsies. They work with the police death investigation team. The clinical forensic medicine services include the issuance of medical reports/certificates (injury following physical assaults, sexual assaults, road traffic accidents, birth, death, stillbirth, fitness, etc.) and as an expert witness in courts. No additional training in clinical forensic medicine is required for those clinicians to provide clinical forensic medical services. Any licensed clinician, working either in the private or public healthcare setup could render the above services.29

Japan’s death investigation system is an example of a ‘hybrid model.’ In Japan, both the Police-based death investigation system and Medical examiner’s (ME) system prevail. However, the ME system is available only in three big cities today, such as Tokyo, Kobe, and Osaka city. In Japan too, all unnatural deaths must be informed to the Police. Unnatural deaths, as defined explicitly in the ‘Japanese Medical Practitioners Law’ include 1) deaths due to external causes [unexpected accidents, traffic accidents, falls of all types, drowning, deaths caused by fire, asphyxiation, poisoning, exposure to the abnormal environment, electrocution]; 2) suicides; 3) homicides; 4) unexpected death related to medical action or suspicion/without evident cause, and 5) deaths resulting from unknown causes. Briefly, when unnatural deaths are reported to the Police, an IPO studies the circumstances and a medical examiner performs external body examinations. If suspected to be criminal, a judicial autopsy is performed. An administrative autopsy or a consent autopsy is performed (not always) to rule out hidden crimes and for public health purposes in non-criminal cases. It is to be noted that all the judicial autopsies are performed in the forensic medicine departments in Japan. The ME centers can perform only administrative or consent autopsies. Most forensic departments and medical examiner’s centers are equipped with CT scanners which facilitate the death investigations. Similarly, Police forensic laboratories all over Japan are well-equipped for various ancillary investigations.29, 30

FORENSIC MEDICINE IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA (USA)

The Coroner system was transplanted in the USA during the British colonial period as early as 1635. Yet, the first medicolegal autopsy in the USA was performed in Maryland in 1665. In 1877, the ME system was established in Massachusetts, and by the early 1900s, the Coroner system in the USA was entirely replaced with the ME system. In the ME system in the USA, the medical examiners investigate suicides, accidental deaths of any kind, and all criminal deaths. The medical examiner’s office has its forensic pathologists who have the full authority to decide on the autopsy and determine both the cause and manner of death. Like in Japan, medical examiners/forensic pathologists do not involve in clinical forensic medical services. As such, the USA too follows a ‘divided service’ system. Forensic science laboratories are highly advanced in the USA and are available nationwide.31, 32

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The formal practice of forensic medicine in South Asia like the developed countries (Japan and the USA) commenced in a comparable period. Despite having a deep historical influence, each has evolved and taken its course of evolution. This is evident from the fact that the British Coroner system once transplanted across South Asia and in the USA has largely been replaced by the Police-led death investigation system in South Asia, and by the ME system in the USA, respectively. Comparably, Japan also remodeled its medicolegal system from the German-based to the ‘hybrid model’ after the Second world war. South Asian countries have adopted the ‘integrated service’ system, whilst Japan and the USA practice ‘divided service’ systems as forensic medicine advanced in their own countries. This must be the reason South Asian countries stress forensic medicine education in medical training. It is expected that a medical graduate is capable to handle all the medicolegal work including autopsies, particularly in South Asia. This is in sharp contrast to Japan and the USA, where a forensic pathologist or a medical examiner needs additional training to be certified to perform autopsies.

The pace of development and modernization of forensic medicine is not parallel within and between South Asia, and between South Asia and developed countries. The practice of forensic medicine in the USA and Japan is so advanced today. Their higher standard of practice is facilitated by friendly and modern legislation, adequate resource allocations, and huge incentives for forensic medical practitioners all favoring revolution of forensic medicine. In south Asian countries, the practice of forensic medicine is often compromised by deficient/outdated legislations, scarcity of medical practitioners, poor infrastructural facilities, and low incentives for forensic medical practitioners. This is also compounded by the fact that deep religious and cultural sentiments overshadow the necessity to advance forensic medicine in some South Asian countries. For example, due to the reasons stated above, the creation of the Department of Forensic Medicine and Toxicology at JDWNRH in Bhutan occurred not until 2005. Moreover, in Afghanistan and Bhutan, a full-body autopsy is often considered unnecessary and said to carry social stigmas to the medical practitioners if performed.18 In Japan and USA, forensic medical practitioners do not have these religious and cultural difficulties in delegating their duties.

Most South Asian countries follow a Police-led death investigation system. The Police play a decisive role in death investigation processes including authorization for autopsies. This system has several flaws; the scope is limited to finding the criminality, and completely ignores other purposes of death investigations. Because of this investigative nature, medical doctors have fewer inputs in the death investigation process. In the Sri Lankan context, the existence of a Coroner system/ISD in addition to the Magistrate’s office is advantageous since it is broadening the scope of death investigations. In particular, it incorporates the concerns from public health and statistical viewpoints, which ultimately gives feedback to the policy advancements. However, like in the Police-based death investigation systems, forensic medical practitioners have limited involvement. In the ‘hybrid model’ of the Japanese death investigation system, indeed the Police play a bigger role, medical doctors also get to contribute equally or even more through the ME system. The mechanism to investigate all unnatural deaths exist in Japan, but the true benefit of the system is yet to be realized. The ME system in the USA is impressive. It functions independently and has the authority to investigate all unnatural deaths and determine both the cause and manner of deaths.

In moving forward, to improve and revamp the existing status quo of forensic medicine in South Asia, the authors recommend several key priorities. Specifically, it needs to start by enacting and implementing relevant and modern legislation that promotes forensic medicine. The law on ‘Postmortem autopsies’ and ‘Cremation’ must be amended as soon as possible. This is genuine in the case of Afghanistan and Bhutan, where the relatives of the deceased hurriedly cremate the body even when there is an element of true crime. With legislation, public education must be campaigned to dispel religious and cultural beliefs surrounding full-body autopsies. Autopsies must be viewed as a process to serve legal justice to the deceased and have more superior aims. If performing autopsies are difficult due to a lack of human resource or infrastructure, there need to be alternative arrangements designed to investigate the death. For example, postmortem computed tomography, which is non-destructive, yet yields comparable findings to a full-body autopsy could be attempted hand in hand with the clinical radiological departments of the hospitals. Limiting to external body inspections could lead to overlooking concealed crimes. Also, from the lens of public health and national statistics, countries should start investigating unnatural deaths more seriously. Bhutan uses morbidity and mortality data to plan and prioritize its healthcare programs. In 2019, hospital deaths constituted only 36.3% of annual total deaths (3220), which had proper medical certification of cause of death. On the other hand, out-of-hospital deaths (home, unknown places, etc.) were as high as > 60%, which were less investigated, or no proper cause of death was determined.33 It is questionable how seriously the policymakers in Bhutan considered this issue. It is rather high time now that the concerned government and relevant stakeholders take cognizance of the above issues and start investing more resources in forensic medicine in South Asia. A substandard medicolegal service is as bad as no justice served to the deceased and victims alike.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments: We are grateful to Dr. Duptho Sonam (General physician, JDWNRH) for sharing his experience of medicolegal practice in Bhutan, and to the staff of the Forensic Medicine and Toxicology Department, JDWNRH for their valuable assistance in sharing the relevant data.

The abstract and the concept of the paper were presented at the 2019 36th Chugoku-Shikoku Regional meeting of the Japanese Society of Legal Medicine, in Yonago, Japan.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Meilia PDI,Freeman MD,Herkutanto, Zeegers MP. A review of the diversity in taxonomy, definitions, scope, and roles in forensic medicine: implications for evidence-based practice. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2018;14:460-8. 10.1007/s12024-018-0031-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kharoshah MAA,Zaki MK,Galeb SS,Moulana AAR,Elsebaay EA. Origin and development of forensic medicine in Egypt. J Forensic Leg Med. 2011;18:10-3. 10.1016/j.jflm.2010.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salgado MSL. Forensic medicine in the Indo-Pacific region: history and current practice of forensic medicine. Forensic Sci Int. 1988;36:3-10. 10.1016/0379-0738(88)90208-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Syukriani YF,Novita N,Sunjaya DK. Development of forensic medicine in post reform Indonesia. J Forensic Leg Med. 2018;58:56-63. 10.1016/j.jflm.2018.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Waheeb S,Al-Kandary N,Aljerian K. Forensic autopsy practice in the Middle East: comparisons with the west. J Forensic Leg Med. 2015;32:4-9. 10.1016/j.jflm.2015.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathiharan K. Origin and development of forensic medicine in India. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2005;26:254-60. 10.1097/01.paf.0000163839.24718.b8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zaidi S,Saligram P,Ahmed S,Sonderp E,Sheikh K. Expanding access to healthcare in South Asia. BMJ. 2017;357:j1645. 10.1136/bmj.j1645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.David S,Gazi R,Mirzazada MS,Siriwardhana C,Soofi S,Roy N. Conflict in South Asia and its impact on health. BMJ. 2017;357:j1537. 10.1136/bmj.j1537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shrestha R,Krishan K,Kanchan T. Medico-legal encounters of 2015 Nepal earthquake – Path traversed and the road ahead. Forensic Sci Int. 2020;313:110339. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2020.110339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhutan Outraged. 8-year-old raped and murdered in Paro, 5-year-old raped in Dagana and 4-year-old molested in Thimphu – The Bhutanese [Internet]. Thimphu: The Bhutanese; 2019. [cited 2020 May 28]. Available from: https://thebhutanese.bt/bhutan-outraged-8-year-old-raped-and-murdered-in-paro-5-year-old-raped-in-dagana-and-4-year-old-molested-in-thimphu/

- 11.Mateen RM,Tariq A,Rasool N. Forensic science in Pakistan; present and future. Egypt J Forensic Sci. 2018;8:45. 10.1186/s41935-018-0077-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Islam MN,Islam MN. Forensic medicine in Bangladesh. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2003;5(suppl 1):S357-9. 10.1016/S1344-6223(02)00132-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmad N,Busuttil A,Path FRC. Medicolegal Practice in Pakistan. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1993;14:262-7. 10.1097/00000433-199309000-00018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hadi S. Medicolegal impact of the new hurt laws in Pakistan. J Clin Forensic Med. 2003;10:179-83. 10.1016/S1353-1131(03)00074-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruwanpura RP,Vidanapathirana M. Historical landmarks of the evolution of forensic medicine and comparative development of medico-legal services in Sri Lanka. Medico-Legal Journal of Sri Lanka. 2018;6:1. 10.4038/mljsl.v6i1.7366 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balachandra AT,Vadysinghe AN,William AL. Practice of forensic medicine and pathology in Sri Lanka. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:187-90. 10.5858/2008-0397-CCR.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Subedi ND,Deo S. Status of medico legal service in Nepal: problems along with suggestions. Journal of College of Medical Sciences-Nepal. 2015;10:49-54. 10.3126/jcmsn.v10i1.12769 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rahiq F,Xiquang L,Rehman M,Zahed A,Pashtoonyar KA,Taseer BA,et al. Suicide Cases and Causes Reported in Forensic Medicine Directorate and Isteqlal Hospital of the Ministry of Public Health, Kabul Afghanistan. IJMER. 2020;9:52-86. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Statistical Yearbook of Bhutan. 2020. [Internet]. Thimphu: National Statistics Bureau; 2021 [cited 2021 Mar 17]. Available from: https://www.nsb.gov.bt/publications/statistical-yearbook/

- 20.Yangchen S,Tobgay T,Melgaard B. Bhutanese health and the health care system: past, present, and future. Druk J. 2017;2020:1-10. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dorji T,Melgaard B. Medical History of Bhutan. 2nd ed. Thimphu: Centre for Research Initiatives Changangkha; 2018. 343 p. [Google Scholar]

- 22.The Royal Bhutan Police Act, 1980, Part One [Internet]. Thimphu: Royal Bhutan Police; 2009. [cited 2021 Mar 16]. Available from: https://www.nationalcouncil.bt/assets/uploads/docs/acts/2020/Royal%20Bhutan%20Police%20Act%20of%20Bhutan%201980_Eng.pdf

- 23.Royal Bhutan police. Royal Bhutan Police Act 2009 [Internet]. Thimphu: Royal Bhutan Police; 2009. [Cited 2021 Mar 16]. Available from: https://www.rbp.gov.bt/Forms/Police Act.pdf.

- 24.JDWNRH – National Referral Hospital [Internet]. Thimphu: JDWNRH; 2018. [cited 2021 Mar 15]. Available from: https://www.jdwnrh.gov.bt/

- 25.Atreya A,Menezes RG,Subedi N,Shakya A. Forensic medicine in Nepal: Past, present, and future. J Forensic Leg Med. 2022;86:102304. 10.1016/j.jflm.2022.102304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kodikara S. Practice of clinical forensic medicine in Sri Lanka: does it need a new era? Leg Med (Tokyo). 2012;14:167-71. 10.1016/j.legalmed.2012.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Menezes RG,Arun M,Krishna K. Death Investigation Systems: India. Encyclopedia of Forensic and Legal Medicine. 2016:18-24. 10.1016/B978-0-12-800034-2.00396-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ishihara K,Iwase H. Reform of the death investigation system in Japan. Med Sci Law. 2020;60:216-22. 10.1177/0025802420916590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sawaguchi T,Knight B. Legal Aspects of Medical Practice in Britain and Japan. 1st ed. Tokyo: Toyo Shoten; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fujimiya T. Legal medicine and the death inquiry system in Japan: A comparative study. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2009;11(suppl 1):S6-8. 10.1016/j.legalmed.2009.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choo TM,Choi YS. Historical Development of Forensic Pathology in the United States. Korean J Leg Med. 2012;36:15. 10.7580/KoreanJLegMed.2012.36.1.15 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.James SH,Nordby JJ,Bell S. Forensic science: An introduction to scientific and investigative techniques: 4th ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press/Taylor & Francis Group; 2014. 10.1201/b16445 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ministry of Health. Royal Government of Bhutan [Internet]. Thimphu: Ministry of Health, 2022. [cited 2022 Jan 10]. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.bt/