Abstract

The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is unique among eukaryotes in exhibiting fast growth in both the presence and the complete absence of oxygen. Genome-wide transcriptional adaptation to aerobiosis and anaerobiosis was studied in assays using DNA microarrays. This technique was combined with chemostat cultivation, which allows controlled variation of a single growth parameter under defined conditions and at a fixed specific growth rate. Of the 6,171 open reading frames investigated, 5,738 (93%) yielded detectable transcript levels under either aerobic or anaerobic conditions; 140 genes showed a >3-fold-higher transcription level under anaerobic conditions. Under aerobic conditions, transcript levels of 219 genes were >3-fold higher than under anaerobic conditions.

Aerobic organisms have evolved a multitude of defense mechanisms to protect themselves against oxygen, which is highly toxic to obligately anaerobic organisms. In addition to its role as electron acceptor in aerobic respiration, aerobes require molecular oxygen for various biosynthetic reactions (e.g., the oxygenase reactions involved in the synthesis of sterols and unsaturated fatty acids) (1, 2). Anaerobes have to bypass these oxygen-requiring reactions, either by acquiring their products from the environment or by using alternative pathways.

Most identified yeast species can ferment sugars to ethanol and carbon dioxide (24). Thus, they do not depend on oxygen for their dissimilatory metabolism and grow rapidly under oxygen-limited conditions. Only very few species can grow in the complete absence of oxygen (27). In fact, the most important yeast species in fundamental and applied research, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, stands out among yeasts and among eukaryotes with respect to its rapid growth under aerobic as well as strictly anaerobic conditions (27). In combination with the availability of its complete genome sequence (13), this makes S. cerevisiae an ideal model organism with which to study physiological adaptation to aerobiosis and anaerobiosis in eukaryotes. Research into the physiological mechanisms that enable S. cerevisiae to grow anaerobically is not only of fundamental scientific interest: oxygen requirement is a key factor in the application of yeasts in the production of alcoholic beverages and fuel ethanol (7, 22).

Genome-wide transcription analysis is a powerful tool for determining the complete set of mRNAs and their relative expression levels as a function of growth conditions. All studies published to date on genome-wide transcription in S. cerevisiae rely on the use of batch cultures (6, 10, 14, 30). The inherent drawback of this cultivation method is that it does not allow studies of the effect of individual cultivation parameters. For example, in standard shake flask cultures of yeasts, essential culture parameters such as pH, dissolved-oxygen concentration, and concentration of nutrients change continuously during growth. Even when pH and dissolved-oxygen concentrations are controlled (e.g., by using fermentor cultures), physical and chemical culture parameters cannot be manipulated independent of the specific growth rate. Since the specific growth rate has a drastic impact on the regulation of gene expression (11, 21), this readily obscures interpretation of the transcriptional patterns derived from such batch cultures.

Chemostat cultivation allows reproducible steady-state cultivation of microorganisms (20). In chemostat cultures, important parameters such as the specific growth rate, culture pH, and dissolved-oxygen concentration can be accurately controlled. Thus, chemostat cultivation allows physiological studies in which a single culture parameter is varied while all other conditions are kept constant (20, 29). This makes chemostat cultivation a virtually indispensable technique for genome-wide expression studies.

In this study, glucose-limited chemostat cultures of S. cerevisiae, grown at a fixed specific growth rate, pH, and temperature, were used to compare the aerobic and anaerobic transcript profiles of this yeast.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strain and growth conditions.

The prototrophic laboratory strain S. cerevisiae CEN.PK113-7D (MATa) was kindly provided by P. Kötter (J.-W. Goethe Universität, Frankfurt, Germany). Steady-state chemostat cultures were grown in 1-liter working-volume Applikon laboratory fermentors as described in detail elsewhere (23). In brief, the cultures were fed with a defined mineral medium containing glucose as the growth-limiting nutrient (25). The dilution rate (which equals the specific growth rate) in the steady-state cultures was 0.10 h−1, the temperature was 30°C, and the culture pH was 5.0. Aerobic conditions were maintained by sparging the cultures with air (0.5 liter · min−1). The dissolved-oxygen concentration, which was continuously monitored with an Ingold model 34 100 3002 probe, remained above 80% of air saturation. For anaerobic cultivation, the reservoir medium was supplemented with Tween 80 and ergosterol as described by Verduyn et al. (26). Anaerobic conditions were maintained by sparging the medium reservoir and the fermentor with pure nitrogen gas (0.5 liter · min−1). Furthermore, Norprene tubing and butyl rubber septa were used to minimize oxygen diffusion (27). Residual glucose concentrations in the aerobic and anaerobic chemostat cultures, assayed after rapid sampling in liquid nitrogen (11), were 0.17 and 0.40 mmol · liter−1, respectively.

mRNA isolation and cDNA preparation.

Cells for RNA isolation were harvested by a rapid sampling procedure, as induction of aerobic genes has been shown to occur within minutes after exposure of anaerobic cultures to oxygen (reference 5 and our unpublished results). Due to the large volumes, samples from the fermentor could not be harvested directly in liquid N2. We therefore collected 50-ml samples in a predetermined amount of ice in a centrifuge bucket placed in an ice-salt bath at −5°C such that the temperature of the sample dropped to 2°C within 15 s. The mixtures were centrifuged at the same temperature, and the pellets were frozen in liquid N2.

For total RNA extraction, the frozen pellet of 50 ml of culture was resuspended in 15 ml of phenol (pH 8.0), 15 ml of bead buffer (75 mM ammonium acetate, 10 mM EDTA), and 1 ml of 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate. After the addition of 5 g of glass beads (425- to 600-μm diameter, acid washed), the sample was vortexed twice for 1 min, incubated at 65°C in a water bath for 15 min, and vortexed again for 1 min. The upper phase was extracted with phenol-chloroform (50:50) and subsequently precipitated by adding 1/10 volume of 7.5 M ammonium acetate and 2 volumes of absolute ethanol. Poly(A)+ RNA was purified by using Oligotex-dT (Qiagen).

First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed by mixing 20 μg of poly(A)+ RNA with 3,000 pmol of dT21 in a final volume of 200 μl of 1× first-strand buffer (Gibco). The mixture was incubated at 65°C for 10 min and subsequently cooled on ice; 12 μl of 100 mM dithiothreitol, 4 μl of 20 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (Pharmacia), and 20 μl of Superscript II (200 U/μl; Gibco) were added, and reverse transcription was carried out at 42°C for 60 min, followed by the addition of 3 μl of bacterial DNA control mix to enable assessment of variation in the effectiveness of the labeling procedure. The mixture was extracted with phenol-chloroform (50:50), and cDNA was precipitated by adding 0.5 volume of 7.5 M ammonium acetate and 2.5 volumes of absolute ethanol.

Hybridization and data processing.

The cDNA was fragmented to an average size of approximately 50 bp by DNase I in 1× One-phor-all buffer (Pharmacia) containing CoCl2. After incubation at 37°C for 5 min, the DNase I was inactivated by incubation in a boiling water bath for 10 min. cDNA fragments were 3′ end labeled by a 60-min incubation at 37°C in the presence of biotinylated ddATP and terminal transferase (Boehringer). The hybridization mixture was prepared by adding 125 μl of 2× ST-T (2 M NaCl, 20 mM Tris [pH 7.6], 0.010% Triton X-100), 2 μl of herring sperm DNA (10 mg/ml), and 1 μl of control DNA (strain 948B; 5 nM in 6× SSPE-T [6× SSPE-T contains 0.9 M NaCl, 60 mM NaH2PO4, 6 mM EDTA, and 0.005% Triton X-100, adjusted to pH 7.6]) to the biotinylated cDNA, and the volume was adjusted to 250 μl. After incubation in a boiling water bath for 10 min followed by chilling on ice for 5 min, 200 μl of the target preparation was transferred into a prewetted chip chamber. Hybridizations were carried out at 43°C for 16 h, rotating at 60 rpm. Subsequently the hybridization mixture was collected and stored at −80°C for further use. The chip was rinsed with 6× SSPE-T, washed on a fluidics station (10 washes with 6× SSPE-T and 2 washes with 0.5× SSPE-T), rotated with SSPE-T at 43°C for 15 min, and then rinsed with 6× SSPE-T. The hybridized chips were stained by rotation with 0.4 μl of a 1-mg/ml streptavidin-phycoerythrin solution (Molecular Probes) and 10 μl of a 20-mg/ml bovine serum albumin solution in 190 μl of 6× SSPE-T at 43°C for 10 min. Prior to scanning, the chip was rinsed with 6× SSPE-T and washed on a fluidics station (five washes with 6× SSPE-T).

After subtraction of the values of the mismatch oligonucleotides, intensities of the signals were normalized to the total intensities of the chips. For the eight chips used (two sets of four), these values varied between 979,735 and 1,908,932 arbitrary units.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Genome-wide transcription patterns were analyzed in aerobic and anaerobic, steady-state chemostat cultures of the prototrophic laboratory strain S. cerevisiae CEN.PK113-7D (MATa) (9) using Affymetrix Ye6100 gene chips, which represent a DNA array encompassing virtually the entire S. cerevisiae genome. After scanning the arrays, data analysis was performed with Affymetrix GeneChip software. Transcript levels in aerobic and anaerobic cultures (which were hybridized to different gene chips) were compared after normalization. This involved division of individual fluorescence intensities through the fluorescence of the entire chip. The complete data set is available online (15).

Reliability of the DNA array analysis was evaluated by comparing transcript levels of three reference genes in the aerobic and anaerobic cultures with classical Northern data from the same RNA samples (Table 1). In addition, commonly used mRNA loading standards such as ACT1 (18), PDA1 (28), and HHO1 (21) exhibited the same transcript levels (<10% difference) in aerobic and anaerobic cultures. The measured aerobic/anaerobic values were 3,669/3,839 for ACT1, 2,561/2,687 for PDA1, and 2,083/2,071 for HHO1. Mating type a-specific genes (MFA1, MFA2, and STE2) were expressed in both cultures, whereas only low transcript levels of α-specific genes (MFα1, MFα2, and STE3) were detected. Few data are available from conventional Northern studies on transcription in aerobic and anaerobic chemostat cultures. However, published data from Northern studies for MAE1 (three- to fourfold-higher level in the anaerobic cultures) and ACS1 (present only under aerobic conditions) agreed well with our data (4, 23). For ACS2 (similar levels in aerobic and anaerobic cultures), a slight increase was previously reported (23).

TABLE 1.

Comparison of chip results to Northern data

| Gene | Chip (arbitrary units)

|

Chip ratio, anaerobe/aerobe | Northern ratioa | Comment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anaerobe | Aerobe | ||||

| CYC1 | 1,283 | 3,621 | 1:2.8 | 1:7.3 | Same RNA sample (this study) |

| ROX1 | 289 | 1,237 | 1:4.3 | 1:9.8 | Same RNA sample (this study) |

| DAN1 | 5,726 | 143 | 40:1 | >40:1b | Same RNA sample (this study) |

| MAE1 | 1,709 | 392 | 4.4:1 | 3-4:1 | Same strain, same conditions, different samples (4) |

| ACS1 | 340 | 2,180 | 1:6.4 | >6.4b | Different strain, same conditions (23) |

| ACS2 | 2,895 | 2,755 | 1.1:1 | 2.8:1 | Different strain, same conditions (23) |

From phosphorimager read-outs normalized to the ACT1 or PDA1 mRNA signal.

Anaerobic signal was 0.

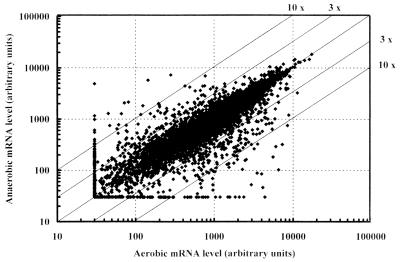

In the glucose-limited chemostat cultures, 5,738 (93%) of 6,171 open reading frames (ORFs) from the S. cerevisiae genome were transcribed at a detectable level under either aerobic or anaerobic conditions (Fig. 1). This fraction is higher than reported for previous genome-wide transcription studies on batch cultures of S. cerevisiae (30) and may reflect the alleviation of glucose catabolite repression that occurs as a result of the low residual glucose concentration in glucose-limited chemostat cultures (9, 21).

FIG. 1.

Transcript levels of 6,171 yeast ORFs represented on the Affymetrix Ye6100 gene chips in aerobic and anaerobic chemostat cultures (dilution rate = 0.10 h−1; pH 5.0; temperature = 30°C) of S. cerevisiae CEN.PK113-7D. Transcripts that were considered absent by the Affymetrix software are set at a value of 30 to allow calculation of a ratio. The diagonal lines indicate various ratios between aerobic and anaerobic transcript levels.

The majority of the yeast genes showed similar transcript levels under aerobic and anaerobic conditions (Fig. 1). Only 219 genes showed a >3-fold-higher transcription level under aerobic conditions. Under anaerobic conditions, transcript levels of 140 genes were >3-fold higher than aerobically. Only a very small number of genes exhibited a >10-fold difference between aerobic and anaerobic mRNA levels (examples given in Tables 2 and 3).

TABLE 2.

Aerobic genes

| ORFa | Gene name | mRNA level (arbitrary units)

|

Ratio, aerobic/anaerobic | Similarity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anaerobic | Aerobic | ||||

| YOR388C | FDH1 | Ab | 4,609 | ||

| YPL275W | A | 4,389 | YOR388C | ||

| YPL276W | A | 2,368 | YOR388C | ||

| YDR256C | CTA1 | A | 2,076 | ||

| YHR096C | HXT5 | A | 1,846 | ||

| YNL195C | A | 1,578 | Unknown | ||

| YGR110W | A | 1,497 | Unknown | ||

| YCR010C | A | 1,489 | Unknown | ||

| YDL218W | A | 1,189 | Unknown | ||

| YPL223C | GRE1 | 102 | 6,535 | 64 | |

| YJR095W | ACR1 | 52 | 2,956 | 57 | |

| YMR303C | ADH2 | 85 | 3,992 | 47 | |

| YGR236C | 88 | 3,491 | 40 | ||

| YHR139C | SPS100 | 125 | 4,477 | 36 | |

| YPR151C | 182 | 5,560 | 31 | Unknown | |

| YMR107W | 320 | 7,282 | 23 | Unknown | |

| YMR118C | 104 | 2,273 | 22 | Unknown | |

| YLR174W | IDP2 | 291 | 6,026 | 21 | |

| YPL201C | 162 | 2,545 | 16 | Unknown | |

| YDR380W | 156 | 2,456 | 16 | Unknown | |

| YMR058W | FET3 | 114 | 1,538 | 13 | |

| YBR047W | 138 | 1,772 | 13 | Unknown | |

| YML054C | CYB2 | 262 | 3,202 | 12 | |

| YLR205C | 162 | 1,968 | 12 | Unknown | |

| YPL147W | PXA1 | 133 | 1,520 | 12 | |

| YDR070C | 749 | 8,479 | 11 | Unknown | |

| YPR001W | CIT3 | 130 | 1,452 | 11 | |

| YER065C | ICL1 | 136 | 1,527 | 11 | |

| YKR009C | FOX2 | 325 | 3,546 | 11 | |

| YLL053C | 94 | 1,022 | 11 | Unknown | |

| YGR256W | GND2 | 189 | 1,948 | 10 | |

ORF with an aerobic/anaerobic ratio of at least 10 and with an aerobic expression level of 1,000 or more.

A, absence of transcription according to the Affymetrix software.

TABLE 3.

Anaerobic genes

| ORFa | Gene name | mRNA level (arbitrary units)

|

Ratio, anaerobic/aerobic | Similarity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anaerobic | Aerobic | ||||

| YMR319C | FET4 | 1,159 | Ab | ||

| YPR194C | 982 | A | Oligopeptide transporter | ||

| YIR019C | STA1/FLO11 | 981 | A | ||

| YHL042W | 608 | A | Unknown | ||

| YHR210C | 552 | A | Gal10p | ||

| YGL162W | SUT1/STO1 | 371 | A | ||

| YHL044W | 334 | A | Unknown | ||

| YOL015W | 320 | A | Unknown | ||

| YJR047C | ANB1/TIF51B | 4,901 | 21 | 231 | |

| YJR150C | DAN1 | 5,726 | 143 | 40 | |

| YML083C | 2,056 | 72 | 29 | Unknown | |

| YBR085W | AAC3 | 1,281 | 45 | 28 | |

| YOR010C | TIR2 | 2,140 | 81 | 27 | |

| YER011W | TIR1 | 7,262 | 278 | 26 | |

| YKR053C | YSR3/LBP2 | 1,268 | 66 | 19 | |

| YER188W | 746 | 47 | 16 | Unknown | |

| YCL025C | AGP1 | 1,817 | 123 | 15 | |

| YPL265W | DIP5 | 772 | 61 | 13 | |

| YDL241W | 645 | 58 | 11 | Unknown | |

| YBL029W | 1,223 | 116 | 11 | Unknown | |

| YDR044W | HEM13 | 4,420 | 422 | 11 | |

| YLR413W | 2,006 | 194 | 10 | Unknown | |

ORF with an anaerobic/aerobic ratio of at least 10 and an anaerobic expression level of 300 or more.

A, absence of transcription according to the Affymetrix software.

Surprisingly, the majority of genes involved in respiratory sugar metabolism (e.g., those encoding enzymes of the tricarboxylic acid cycle or proteins involved in respiration) showed little or no repression under anaerobic conditions. This result appears to contradict earlier work by DeRisi et al. (10), who found that transcription of most genes involved in respiration was strongly induced upon a switch from fermentative growth to respiratory growth. However, this contradiction is only apparent. In the experiments of DeRisi et al., the shift from fermentative metabolism to respiratory metabolism was accomplished by growing S. cerevisiae on glucose in batch cultures. This results in a typical diauxic pattern because initially, the high sugar concentration in the medium causes glucose catabolite repression of respiratory enzymes (12, 16). Only when glucose is exhausted and cells start consuming ethanol this repression is relieved. In our experiments, aerobic and anaerobic growth were studied in glucose-limited chemostat cultures in which the low residual glucose concentrations alleviated glucose repression. Apparently, under these conditions, the flux through the tricarboxylic acid cycle and respiration is primarily regulated posttranscriptionally (e.g., by concentrations of intracellular metabolites and effectors).

The physiological functions of several of the 53 genes which exhibited a strongly (>10-fold) elevated transcript level under aerobic conditions could be directly linked to typical aerobic processes. This group includes genes involved in respiration [e.g., NDE2, encoding an isoenzyme of the mitochondrial external NADH dehydrogenase; YMR118c, encoding a succinate dehydrogenase; and CYB2, encoding a cytochrome b-(l-lactate cytochrome c oxidoreductase)], protection against oxygen toxicity (CTA1, encoding the peroxisomal isoenzyme of catalase), and β oxidation (PXA1, encoding a transporter involved in translocation of long-chain fatty acids across the peroxisomal membrane; and FOX2, encoding 3-hydroxyacyl coenzyme A epimerase). For some other genes that were specifically expressed under aerobic conditions, the role in aerobic metabolism was less obvious, either because they encode proteins with unknown function (Table 2) or because the known functions of their protein products could not be clearly correlated with aerobic growth. This holds, for example, for the sporulation-specific gene SPS100 (Table 2), which exhibited a 36-fold-higher transcript level in aerobic cultures, even though sporulation did not occur in these cultures. Also, the high expression of three genes presumed to encode formate dehydrogenases (Table 2) in aerobic cultures is unclear.

A comparison of the aerobic and anaerobic transcript profiles of wild-type S. cerevisiae does not by itself allow conclusions about the molecular mechanisms of transcriptional regulation. However, the methodology used for this study is, in principle, well suited for disentangling the regulatory network via comparison of transcript profiles in wild-type strains and strains with defined modifications in regulatory genes. Some indication as to the involvement of known regulatory mechanisms can be obtained from the presence of consensus sequences in the promoters of aerobically and anaerobically induced genes. For example, 7 of the 11 previously identified Rox1-binding-site-containing hypoxic genes (SUT1, ANB1, HEM13, HMG2, AAC3, ROX1, and COX5b) (8, 17) showed elevated transcript levels under anaerobic conditions. It is not clear whether the marginal (1.3-fold) increases of the CPH1/CPR1 and OLE1 and the unchanged ERG11 and CYC7 mRNA levels are caused by the stringent anaerobic conditions in the fermentor cultures used in this study.

The functions of some of the genes exhibiting a strongly elevated transcript level under anaerobic conditions (Table 3) could be directly linked to anaerobic metabolism. For example, the anaerobic induction of SUT1, encoding a protein involved in sterol uptake (Table 3), can be directly linked to the strict requirement for uptake of exogenous sterols in anaerobic cultures. Similarly, the requirement of mitochondrial ATP under anaerobic conditions is reflected by the strong (28-fold) induction of AAC3, encoding a mitochondrial ATP/ADP translocator. The high transcript level of FET4, which encodes a low-affinity ferrous iron transporter, is probably related to the fact that in anaerobic cultures, iron is predominantly present as Fe(II). Indeed, aerobic cultivation resulted in the strong (13-fold) induction of FET3, encoding a cell surface ferroxidase required for high-affinity ferrous iron uptake. As for the aerobic genes of S. cerevisiae, the physiological role of many of the anaerobically induced genes remains unclear. This does not only hold for the substantial fraction of these genes that encode proteins with completely unknown function. For example, the roles in anaerobic metabolism of several genes implicated in stress response (DAN1, TIR1, TIR2, and YSR3/LBP2) or amino acid transport (AGP1 and DIP5) remain to be elucidated.

In quantitative terms, the aerobic and anaerobic transcript profiles of S. cerevisiae exhibit little difference. This observation can be interpreted in two ways. One possibility is that only few genes contribute to this eukaryote's unique ability to grow rapidly under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Alternatively, genes with similar aerobic and anaerobic transcription levels may contribute to this metabolic flexibility. Discrimination between these possibilities requires a combination of the results from this study with investigations, under well-defined aerobic and anaerobic conditions, of the fitness of defined null mutants in all yeast genes. In principle, competition experiments with large sets of defined yeast mutants (3) in aerobic and anaerobic chemostat cultures should present an excellent tool for such studies (19).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank our colleagues at Stanford, Leiden, and Delft for stimulating discussions, Marko Kuyper for his contribution to the chemostat experiments, and Theo van Vliet for setting up the website.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andreasen A A, Stier T J B. Anaerobic nutrition of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. I. Ergosterol requirement for growth in a defined medium. J Cell Comp Physiol. 1953;41:23–26. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1030410103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andreasen A A, Stier T J B. Anaerobic nutrition of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. II. Unsaturated fatty acid requirement for growth in defined medium. J Cell Comp Physiol. 1954;43:271–281. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1030430303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baganz F, Hayes A, Marren D, Gardner D J, Oliver S G. Suitability of replacement markers for functional analysis studies in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1997;13:1563–1573. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199712)13:16<1563::AID-YEA240>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boles E, de Jong-Gubbels P, Pronk J T. Identification and characterization of MAE1, the Saccharomyces cerevisiae structural gene encoding mitochondrial malic enzyme. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2875–2882. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.11.2875-2882.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burke P V, Raitt D, Allen L A, Kellogg E A, Poyton R O. Effects of oxygen concentration on the expression of cytochrome c and cytochrome c oxidase genes in yeast. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:14705–14712. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.23.14705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chu S, DeRisi J L, Eisen M, Mulholland J, Botstein D, Brown P O, Herskowitz I. The transcriptional program of sporulation in budding yeast. Science. 1998;282:699–705. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5389.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D'Amore T. Improving yeast fermentation performance. J Inst Brew. 1992;98:375–382. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deckert J, Perini R, Balusubramanian B, Zitomer R S. Multiple elements and auto-repression regulate Rox1, a repressor of hypoxic genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1995;139:1149–1158. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.3.1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Jong-Gubbels P, Vanrolleghem P, Heijnen S, van Dijken J P, Pronk J T. Regulation of carbon metabolism in chemostat cultures of Saccharomyces cerevisiae grown on mixtures of glucose and ethanol. Yeast. 1999;11:407–418. doi: 10.1002/yea.320110503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeRisi J L, Iyer V R, Brown P O. Exploring the metabolic and genetic control of gene expression on a genomic scale. Science. 1997;278:680–686. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diderich J A, Schepper M, van Hoek P, Luttik M A, van Dijken J P, Pronk J T, Klaassen P, Boelens H F M, Teixeira de Mattos J M, van Dam K, Kruckeberg A L. Glucose uptake kinetics and transcription of HXT genes in chemostat cultures of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:15350–15359. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gancedo J M. Carbon catabolite repression in yeast. Eur J Biochem. 1992;206:297–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goffeau A, et al. The yeast genome directory. Nature. 1997;387(Suppl.):5–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hauser N C, Vingron M, Scheideler M, Krems B, Hellmuth K, Entian K-D, Hoheisel J D. Transcriptional profiling on all open reading frames of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998;14:1209–1221. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19980930)14:13<1209::AID-YEA311>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.IMP Website. 1999. [Online.] http://wwwIMP.LeidenUniv.nl/∼Yeast.

- 16.Klein C J L, Olsson L, Nielsen J. Glucose control in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: the role of MIG1 in metabolic functions. Microbiology. 1998;144:13–24. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwast K E, Burke P V, Poyton R O. Oxygen sensing and the transcriptional regulation of oxygen-responsive genes in yeast. J Exp Biol. 1998;201:1177–1195. doi: 10.1242/jeb.201.8.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ng R, Abelson J. Isolation and sequence of the gene for actin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:3912–3916. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.7.3912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pennisi E. From genes to genome biology. Science. 1996;272:1736–1738. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5269.1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pirt S J. Principles of microbe and cell cultivation. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sierkstra L N, Verbakel J M A, Verrips C T. Analysis of transcription and translation of glycolytic enzymes in glucose-limited continuous cultures of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:2559–2566. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-12-2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skoog K, Hahn-Hägerdal B. Xylose fermentation. Enzyme Microbiol Technol. 1988;10:66–80. [Google Scholar]

- 23.van den Berg M A, de Jong-Gubbels P, Kortland C J, van Dijken J P, Pronk J T, Steensma H Y. The two acetyl-coenzyme A synthetases of Saccharomyces cerevisiae differ with respect to kinetic properties and transcriptional regulation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:28953–28959. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.46.28953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Dijken J P, van den Bosch E, Hermans J J, Rodrigues de Miranda L, Scheffers W A. Alcoholic fermentation by “non-fermentative” yeasts. Yeast. 1986;2:123–127. doi: 10.1002/yea.320020208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verduyn C, Postma E, Scheffers W A, van Dijken J P. Physiology of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in anaerobic glucose-limited chemostat cultures. Microbiol Rev. 1990;58:616–630. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-3-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Verduyn C, Postma E, Scheffers W A, van Dijken J P. Effect of benzoic acid on metabolic fluxes in yeasts: a continuous-culture study on the regulation of respiration and alcoholic fermentation. Yeast. 1992;8:501–517. doi: 10.1002/yea.320080703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Visser W, Scheffers W A, Batenburg-van der Vegte W H, van Dijken J P. Oxygen requirements of yeasts. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:3785–3792. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.12.3785-3792.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wenzel T J, Teunissen A W R H, Steensma H Y. PDA1 mRNA: a standard for quantitation of mRNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae superior to ACT1 mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:883–884. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.5.883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weusthuis R A, Pronk J T, van den Broek P J A, van Dijken J P. Chemostat cultivation as a tool for studies on sugar transport in yeasts. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:616–630. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.4.616-630.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wodicka L, Dong H, Mittmann M, Ho M-H, Lockhart D J. Genome-wide expression monitoring in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:1359–1367. doi: 10.1038/nbt1297-1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]