Abstract

Introduction:

There is a lack of information on illicitly manufactured fentanyl and fentanyl analogue-related (IMF) unintentional overdose death trends over time. The study analyzes IMF-related unintentional overdose fatalities that occurred between July 2015 and June 2017 in Montgomery County, Ohio, an area with the highest rates of unintentional overdose mortality in Ohio.

Methods:

LC-MS/MS-based method was used to identify fentanyl analogs and metabolites in 724 unintentional overdose death cases. The Chi-square statistic was used to assess differences over time in demographic and drug-related characteristics.

Results:

The number of unintentional overdose death cases testing positive for IMFs increased by 377% between second half of 2015 and first half of 2017. The majority of decedents were white (82.5%) and male (67.8%). The proportion of fentanyl-only (no other analogs) cases declined from 89.2% to 24.6% (p<0.001), while proportion of fentanyl analogue-containing cases increased from 9.8% to 70.3% (p<0.001) between the second half of 2015 and first half of 2017. The most commonly identified fentanyl analogs were carfentanil (29.7%), furanyl fentanyl (14.1%) and acryl fentanyl (10.2%). Proportion of IMF cases also testing positive for heroin declined from 21.6% to 5.4% (p<0.001), while methamphetamine positive cases increased from 1.4% to 17.8% (p<0.001) over the same time period

Discussion:

Emergence of fentanyl analogs contributed to substantial increases in unintentional overdose deaths. The data indicate a growing overlap between the IMF and methamphetamine outbreaks. Continuous monitoring of local IMF trends and rapid information dissemination to active users are needed to reduce the risks associated with IMF use.

Keywords: Fentanyl, Illicitly Manufactured Fentanyl, Fentanyl Analogs, Carfentanil, Unintentional Overdose Deaths, Ohio

1. Introduction

Since 2013–2014, illicitly manufactured fentanyl (IMF) has emerged as a significant threat to public health, contributing to notable increases in unintentional overdose deaths in the U.S. (Ciccarone, 2017; Jones et al., 2018; NDEWS, 2015; Peterson et al., 2016; Rudd et al., 2016). Ohio has been identified as one of the high burden states in terms IMF-related overdose mortality (Gladden et al., 2016; Rudd et al., 2016). Unintentional overdose deaths in Ohio increased from 2,110 in 2013 to 4,050 in 2016 (Ohio Department of Health, 2017a). Montgomery County (City of Dayton) is an urban county located in southwest Ohio, with a population of over 530,000 persons. Over the past several years, it has become an epicenter of the heroin and IMF epidemic (Ohio Department of Health, 2017a). According to 2011–2016 data, it had average age adjusted death rate of 42.5 per 100,000 population, the highest in Ohio, and several times greater than the national average (Ohio Department of Health, 2017a).

IMF is produced in clandestine laboratories and includes fentanyl analogs that display wide variability in potency. Although there is a lack of reliable data about the precise potency ratios of different types of IMFs, fentanyl is estimated to be between 30–50 times more potent than morphine (Ciccarone et al., 2017) (up to 100 according to other estimates (Suzuki and El-Haddad, 2017)). In contrast, acetyl fentanyl has lower potency, while some reports suggest that carfentanil has about 100 times greater potency compared to fentanyl (Suzuki and El-Haddad, 2017). Such notable variation in potency of IMF products make them even more dangerous and unpredictable in terms of overdose risks. Variations in chemical composition of fentanyl analogs make detection more difficult. Since fentanyl analogs have not been a part of routine toxicology testing at coroner’s offices across the country, there is a lack of consistent data to assess involvement of different IMF-type drugs in unintentional overdose deaths over time (Cicero et al., 2017; Slavova et al., 2017). To address this gap, Wright State University and the Montgomery County Coroner’s Office (MCCO) in Dayton, Ohio collaborated on a study on identification of fentanyl and its analogs/metabolites (IMFs) in unintentional overdose fatalities that occurred in Montgomery County over a 2 year period, between July 2015 and June 2017.

2. Methods

This study analyzes data obtained from the MCCO Toxicology laboratory on all unintentional overdose deaths that tested positive for IMFs and occurred in Montgomery County between July 1, 2015 -June 30, 2017. First, the study developed and validated a liquid-chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)-based method (Strayer et al., 2018) to identify 26 fentanyl analogs, metabolites, and other synthetic opioids in biological matrices at sub ng mL−1 concentrations: 1) 3-Methylfentanyl; 2) 4-ANNP (Despropionyl fentanyl); 3) Acetyl fentanyl; 4) Acetyl fentanyl 4-methylphenethyl; 5) Acryl fentanyl; 6) Alfentanil; 7, 8) Butyryl fentanyl/isobutyryl fentanyl; 9) Butyryl norfentanyl; 10) Carfentanil; 11) Despropionyl para-fluorofentanyl; 12) Fentanyl; 13) Furanyl fentanyl; 14) Furanyl norfentanyl; 15) Norfentanyl; 16, 17) para-Fluorobutyryl/fluoroisobutyryl fentanyl; 18) para-Methoxyfentanyl; 19) Remifentanil; 20) Remifentanil metabolite; 21) Sufentanil; 22) Valeryl fentanyl; 23) AH-7921; 24) U-47700 (detection methods for 24 analogs/metabolites is described in (Strayer et al., 2018)); 25) beta-Hydroxythiofentanyl; 26) para-Fluorofentanyl. (25 and 26 were developed at the MCCO Toxicology laboratory, but not described in (Strayer et al., 2018)). The isomeric forms butyryl fentanyl/isobutyryl fentanyl and para-fluorobutyryl/fluoroisobutyryl fentanyl could not be differentiated. AH-7921 and U-47700 are synthetic opioids not structurally related to fentanyl.

All cases included in this report tested positive for one or a combination of IMFs identified using newly developed LC-MS/MS-based method. Cases from 2015 and first half of 2016 (that were processed by the Coroner before LC-MS/MS became available) were stored if they screened positive for fentanyl and re-tested using the newly developed method. All subsequent accidental overdose cases were routinely tested using LC-MS/MS method. Data on toxicological testing for heroin, pharmaceutical opioids, benzodiazepines, cocaine, and methamphetamine were also obtained. Information on demographic characteristics including age, sex and race was collected for each decedent.

The Chi-square statistic was used to assess differences over time in demographic and drug-related characteristics of IMF-related unintentional overdose cases (for characteristics observed at every time period). The Hommel (Hommel, 1988) method was used to adjust for multiple testing over the 12 characteristics tested to preserve a 0.05 familywise Type I error rate.

3. Results

The dataset included a total of 724 IMF-related unintentional overdose cases that occurred in Montgomery County between July 2015 and June 2017. The number of unintentional overdose death cases testing positive for IMFs increased by 377% from 74 cases in the second half of 2015 to 353 cases in the first half of 2017. Among all 724 cases, 67.8% were males, 82.5% were non-Hispanic White, and 58.3% were between the ages of 25 and 44 years. There were no statistically significant changes in demographic characteristics over time (Table 1).

Table 1:

Characteristics of unintentional IMF-related overdose fatalities analyzed at the Montgomery County Coroner’s Office (Dayton, Ohio), July 2015-June 2017 (N=724).

| CHARACTERISTICS | ALL CASES n (100%) | 2015 July-Dec n (11.1%) | 2016 Jan. −June n (16.0%) | 2016 July-Dec n (25.6%) | 2017 Jan.-June n (47.3%) | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALL IMF-positive cases | N=724 | N=74 | N=125 | N=172 | N=353 | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 491 (67.8) | 53 (71.6) | 90 (72.0) | 110 (66.0) | 238 (67.4) | 0.441 |

| Female | 233 (32.2) | 21 (28.4) | 35 (28.0) | 62 (36.0) | 115 (32.6) / | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| <25 | 48 (6.6) | 8 (10.8) | 9 (7.2) | 10 (5.8) | 21 (5.9) | 0.275 |

| 25–34 | 215 (29.7) | 16 (21.6) | 48 (38.4) | 51 (29.7) | 100 (28.3) | |

| 35–44 | 207 (28.6) | 25 (33.8) | 38 (30.4) | 47 (27.3) | 97 (27.5) | |

| 45–54 | 140 (19.3) | 14 (18.9) | 16 (12.8) | 34 (19.8) | 76 (21.5) | |

| ≥55 | 114 (15.7) | 11 (14.9) | 14 (11.2) | 30 (17.4) | 59 (16.7) | |

| Race | ||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 597 (82.5) | 60 (81.1) | 101 (80.8) | 141 (82.0) | 295 (83.6) | 0.882 |

| African American or Other | 127 (17.5) | 14 (18.9) | 24 (19.2) | 31 (18.0) | 58 (16.4) | |

| Illicit Fentanyl/Analogues (some cases tested positive for more than one IMF) | ||||||

| Fentanyl | 636 (87.8) | 73 (98.6) | 125 (100) | 155 (90.1) | 283 (80.2) | <0.001 |

| Acetyl fentanyl | 28 (3.9) | 8 (10.8) | 3 (2.4) | 8 (4.7) | 9 (2.5) | - |

| Acryl fentanyl | 74 (10.2) | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.2) | 72 (20.4) | - |

| Carfentanil | 215 (29.7) | 0 | 0 | 43 (25.0) | 172 (48.7) | - |

| Furanyl fentanyl | 102 (14.1) | 0 | 1 (0.8) | 39 (22.7) | 62 (17.6) | - |

| Butyryl/isobutyryl fentanyl | 4 (0.6) | 0 | 0 | 1 (°.6) | 3 (0.8) | - |

| Fluoro(iso)butyryl fentanyl | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.6) | 0 | - |

| para-Fluorofentanyl | 2 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.5) | 0 | - |

| Cyclopropyl fentanyl (Crotonyl? | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | - |

| U-47700§§ | 10 (1.4) | 0 | 0 | 4 (2.9) | 5 a-4) | - |

| Fentanyl /Analogue Metabolites | ||||||

| Norfentanyl | 470 (64.9) | 66 (89.2) | 108 (86.4) | 135 (78.5) | 161 (45.6) | <0.001 |

| Despropionylfentanyl (4-ANPP)¶¶ | 144 (19.9) | 7 (9.5) | 10 (8.0) | 45 (26.2) | 82 (23.2) | <0.001 |

| Despropionyl para-Fluorofentanyl | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.6) | 0 | - |

| Furanyl Norfentanyl | 5 (0.7) | 0 | 0 | 3 a.7) | 2 (0.6) | - |

| Butyryl Norfentanyl J | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.6) | 0 | - |

| IMF combinations *** | ||||||

| Fentanyl/Norfentanyl Only (no Analogues) | 361 (49.9) | 66 (89.2) | 121 (96.8) | 87 (50.6) | 87 (24.6) | <0.001 |

| Any Analogue and/or Analogue Combinations | 362 (50.0) | 8 (10.8) | 4 (3.2) | 84 (48.8) | 266 (75.4) | <0.001 |

| Other Drugs | ||||||

| Heroin ††† | 79 (10.9) | 16 (21.6) | 18 (14.4) | 26 (15.1) | 19 (5.4) | <0.001 |

| Any Pharmaceutical Opioid | 128 (17.7) | 17 (23.0) | 13 (10.4) | 10 (11.6) | 78 (22.1) | 0.002 |

| Any Benzodiazepine | 214 (29.6) | 30 (40.5) | 37 (29.6) | 51 (29.7) | 96 (27.2) | 0.155 |

| Cocaine | 313 (43.2) | 27 (36.5) | 54 (43.2) | 77 (44.8) | 155 (43.9) | 0.659 |

| Methamphetamine | 88 (12.2) | 1 (1.4) | 11 (8.8) | 13 (7.6) | 63 (17.8) | <0.001 |

Chi-square test was used to assess differences across 4 time periods. Bold p-value indicates statistical significance at the 0.05 familywise level of significance (adjusting over the 13 tests using the Hommel method). Synthetic opioids not observed at all time periods were not tested.

Synthetic opioid not structurally related to fentanyl. U-47700 is approximately 7.5 times the strength of morphine.

4-ANPP is used as a precursor for the manufacture of fentanyl-type drugs; it is also an impurity found in fentanyl preparations and is a metabolite of fentanyl and furanyl fentanyl.

One case tested positive only for 4-ANPP and thus was not included in any of the 2 categories.

Cases that tested positive for 6-MAM and/or were identified by the coroner as heroin-related.

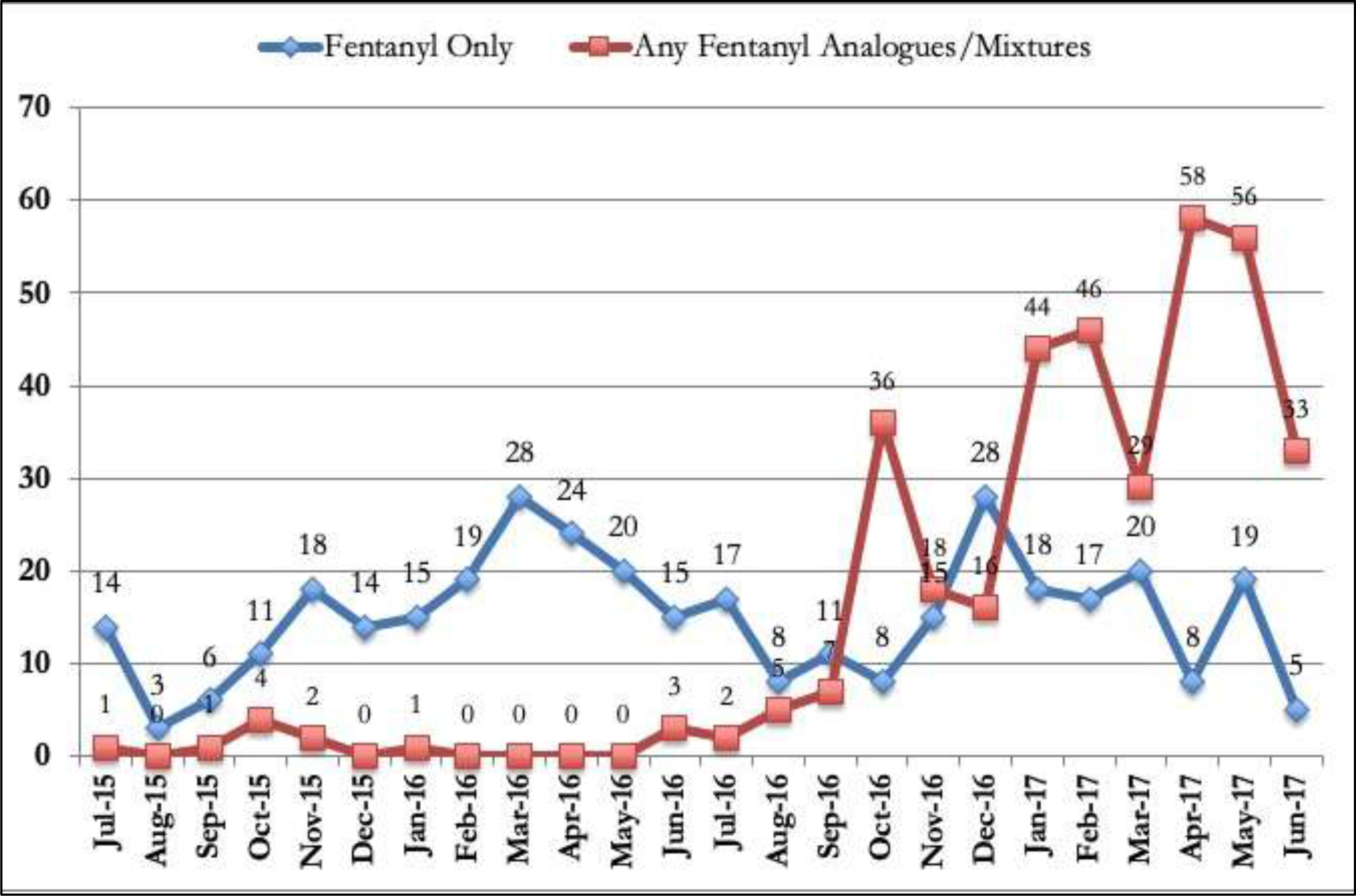

Among all IMF-related unintentional overdose death cases, 87.8% tested positive for fentanyl and 64.9% were positive for norfentanyl, a metabolite of fentanyl. The proportion of fentanyl-positive cases declined over time (p<0.001), as did the proportion positive for norfentanyl (p<0.001) (Table 1). The number of cases testing positive for fentanyl analogs, primarily carfentanil, furanyl fentanyl, and acryl fentanyl increased over time. Carfentanil was identified in 215 (29.7%) of all IMF positive unintentional overdoses. Carfentanil-positive cases first appeared in the summer of 2016, and the numbers increased from 43 (25%) cases in the second half of 2016 to 172 (48.7%) in the first half of 2017 (Table 1). Similarly, acryl fentanyl increased from 1 (1.2%) case in the second half of 2016 to 72 (20.4%) cases in the first half of 2017. Furanyl fentanyl first appeared in the first half of 2016 (1, 0.8%), increasing to 39 cases (22.7%) in the second half of 2016, and 62 cases (17.6%) in the first half of 2017 (Table 1). In contrast, acetyl fentanyl appeared earlier than most other analogs. In the second half of 2015, there were 8 acetyl fentanyl positive cases. Over a 2 year period, 28 cases tested positive for acetyl fentanyl. There were 10 cases positive for U-47700 over two year time period. (Table 1). Overall, while the proportion of fentanyl-only positive cases declined over time from 89.2% in the second half of 2015 to 24.6% in the first half of 2017 (p<0.001), cases testing positive for any fentanyl analogue (or analogue combinations) increased substantially from 10.8% to 75.4% over the same time period (p<0.001) (Table 1, Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Number of unintentional overdose cases testing positive for fentanyl only versus any fentanyl analogs, Montgomery County, July 2015-June 2017.

Many IMF-positive unintentional overdose cases also tested positive for a number of other drugs. The proportion of heroin-positive cases declined from 21.6% in the second half of 2015 to 5.4% in the first half of 2017 (p<0.001). The proportion of pharmaceutical opioid-positive cases differed over time (p<0.001), declining in the first half of 2016 but then increasing in the first half of 2017. Out of all 724 IMF-positive cases, more than 43% tested positive for cocaine. There were no statistically significant changes in the proportion of cocaine-positive cases over time. In contrast, methamphetamine positive cases increased from 1.4% to 17.8% over the same time period (p<0.001) (Table 1).

4. Discussion

Our data suggest that between the second half of 2015 and first half of 2017, there was an almost 4-fold increase in unintentional overdose death cases testing positive for IMFs in Montgomery County, Ohio. Similarly, analysis of unintentional overdose mortality trends at the national level shows notable increases in 2016 and 2017, compared to prior years (Hedegaard et al., 2018). The demographic characteristics of IMF-related unintentional overdose fatalities in our sample are consistent with prior studies showing that IMF users are more likely to be white and male (Carroll et al., 2017; NDEWS, 2017; Somerville et al., 2017). While prior studies focused on synthetic opioids in general (Jones et al., 2018), our results provide information on the heterogeneity of the IMF products detected in unintentional overdose cases.

The results indicate notable declines in overdose cases that tested positive for fentanyl only and surge in cases testing positive for analogs. Up until mid 2016, fentanyl analogs and their combinations were relatively rare among unintentional overdose cased in Montgomery County, while in the first half of 2017, fentanyl analogs accounted for over 75% of all IMF positive cases. Despite increased prevention and intervention efforts in the Montgomery County (Ohio Department of Health, 2017b), emergence of fentanyl analogs contributed to substantial further increases in unintentional overdose death cases related to IMFs.

Our data show a decline in the percentage of IMF-positive overdose cases that also tested positive for heroin. Declining presence of heroin positive cases among unintentional overdose fatalities has been noted in prior reports (Daniulaityte et al., 2017a; Rudd et al., 2016). Our data are consistent with findings from some prior studies suggesting shifts from heroin being contaminated with IMFs (Ciccarone et al., 2017; NDEWS, 2017) to IMF mixtures that do not contain heroin (NDEWS, 2017).

More than 40% of unintentional overdose deaths that tested positive for IMFs also tested positive for cocaine, and this proportion was relatively constant over time. In contrast, a study on IMF outbreak in New Hampshire reported cocaine prevalence among unintentional overdose fatalities at 30% (NDEWS, 2017), while national data showed about 22% prevalence of cocaine positives among synthetic opioid-related overdoses in 2016 (Jones et al., 2018). These differences might be partially related to regional variations in patterns of use. Our prior research found greater prevalence of cocaine positive cases among unintentional overdose fatalities in urban and suburban counties compared to rural counties in Ohio (Daniulaityte et al., 2017a). Use of cocaine is a common practice among illicit opioid users (Kuramoto et al., 2011). However, it is not known if these data indicate a pattern of intended polydrug use or if cocaine and IMF mixtures were sold to unsuspecting illicit opioid and/or cocaine users (Klar et al., 2016; Tomassoni et al., 2017).

Our data show a notable increase in methamphetamine-positive cases over time. Law enforcement reports also indicate an unprecedented surge in availability of high purity methamphetamine in many parts of the country (DEA, 2018a, b). Emerging research suggests growing popularity of methamphetamine use among opioid users to “balance out” the effects of opioids and/or help reduce opioid use (Ellis et al., 2018). There is also a growing concern about increased cases of methamphetamine being contaminated with IMFs (DEA, 2018b). Our results indicate a growing overlap between IMF and methamphetamine epidemics. More research with active drug users is needed to understand attitudinal and behavioral dimensions of the growing methamphetamine problem in the areas ravaged by IMF and other opioid use epidemics.

The findings in this report are subject to several limitations. First, toxicology data on decedents testing positive for multiple drugs cannot determine whether the decedent knowingly or unknowingly ingested combinations of different drugs. Second, because the study re-tested fentanyl ELISA positive cases from second half of 2015 and first half of 2016, some fentanyl analogue-positive cases from that time period might have been missed if they lacked cross-reactivity with the ELISA assay or were at low concentrations. However, available data suggest that notable amount of other fentanyl analogs emerged in the US drug supply in the second half of 2016 (O’Donnell et al., 2017).

These findings highlight the urgent need to continuously update toxicology tests to be able to identify new and emerging fentanyl analogs and other synthetic opioids. Epidemiological surveillance and public health intervention systems need tools for rapid assessment and dissemination of information on emerging substances, not just to the broader public health and scientific communities, but also to active illicit opioid and other drug users in affected communities. Currently, knowledge of IMFs and other synthetic opioids in the community is limited to forensic testing and drug overdose death data in places where adequate testing is available. Active epidemiologic monitoring of IMFs and other drugs from biologic samples of active users could be used to provide rapid assessment tools to inform users about what drugs they were using. There is increased interest in rapid testing technologies for such harm reduction approaches (Harper et al., 2017; Peiper et al., 2019), but additional research is needed to assess their capacity to identify different types of fentanyl analogs and other novel synthetic opioids. More research is needed to better understand the supply-side economics, distribution and marketing strategies associated with increased diversity of fentanyl analogue products. The growing role of dark web-based marketing and distribution of IMFs needs to be better researched and understood (Lokala, 2018).

Although preliminary qualitative data suggest that heroin users may express some confidence in their ability to identify fentanyl (Ciccarone et al., 2017; Mars et al., 2018; NDEWS, 2017), they generally lack knowledge about the existence of different types of fentanyl analogs and synthetic opioids (Daniulaityte, under review; Daniulaityte et al., 2017b). Expanded harm reduction initiatives are needed to educate active drug users about different types of fentanyl analogs, their unique toxicological features, and potential hazardous effects to help reduce the adverse consequences of IMF use. Expansion of access to evidence-based treatment and naloxone provision to those at risk of overdose remains an important strategy for preventing fentanyl-related overdoses.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

This study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Grants: 1R21DA042757 (Daniulaityte, PI) and R01 DA040811 (Daniulaityte, PI). The funding source had no further role in the study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, in the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest No conflict declared.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Carroll JJ, Marshall BDL, Rich JD, Green TC, 2017. Exposure to fentanyl-contaminated heroin and overdose risk among illicit opioid users in Rhode Island: A mixed methods study. Int. J. Drug Policy 46, 136–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarone D, 2017. Fentanyl in the US heroin supply: A rapidly changing risk environment. Int. J. Drug Policy 46, 107–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarone D, Ondocsin J, Mars SG, 2017. Heroin uncertainties: Exploring users’ perceptions of fentanyl-adulterated and -substituted ‘heroin’. Int. J. Drug Policy 46, 146–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Kasper ZA, 2017. Increases in self-reported fentanyl use among a population entering drug treatment: The need for systematic surveillance of illicitly manufactured opioids. Drug Alcohol Depend. 177, 101–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniulaityte R, Carlson R, Juhascik M, Strayer K, Pavel I, (Under Review, Nd). Street fentanyl use: Experiences, preferences, and concordance between self-reports and urine toxicology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniulaityte R, Juhascik MP, Strayer KE, Sizemore IE, Harshbarger KE, Antonides HM, Carlson RR, 2017a. Overdose deaths related to fentanyl and its analogs - Ohio, January-February 2017. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 66, 904–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniulaityte R, Lamy FR, Juhascik M, Sizemore IE, Zatreh M, Strayer KE, Carlson R, 2017b. “That fentanyl dope is way worse”: Characterizing fentanyl outbreaks in the Dayton (Ohio) area. College on Problems of Drug Dependence, Montreal, Canada. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318929062_That_fentanyl_dope_is_way_worse_Characterizing_fentanyl_outbreaks_in_the_Dayton_Ohio_area [Google Scholar]

- Drug Enforcement Administration, (DEA), 2018a. 2017 National Drug Threat Assessment Summary. https://www.dea.gov/documents/2017/10/01/2017-national-drug-threat-assessment

- Drug Enforcement Administration, (DEA), 2018b. National Forensic Laboratory Information System (NFLIS) 2017 Annual Report. U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration; Office of Diversion Control, Washington, DC. https://www.nflis.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/ [Google Scholar]

- Ellis MS, Kasper ZA, Cicero TJ, 2018. Twin epidemics: The surging rise of methamphetamine use in chronic opioid users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 193, 14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladden RM, Martinez P, Seth P, 2016. Fentanyl law enforcement submissions and increases in synthetic opioid-involved overdose deaths - 27 states, 2013–2014. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 65, 837–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper L, Powell J, Pijl EM, 2017. An overview of forensic drug testing methods and their suitability for harm reduction point-of-care services. Harm Reduct. J. 14, 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Warner M, 2018. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2017. NCHS Data Brief National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db329.htm

- Hommel G, 1988. A comparison of two modified Bonferroni procedures. Biometrika 75, 383–386. [Google Scholar]

- Jones CM, Einstein EB, Compton WM, 2018. Changes in synthetic opioid involvement in drug overdose deaths in the United States, 2010–2016. JAMA 319, 1819–1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klar SA, Brodkin E, Gibson E, Padhi S, Predy C, Green C, Lee V, 2016. Notes from the field: Furanyl-fentanyl overdose events caused by smoking contaminated crack cocaine - British Columbia, Canada, July 15–18, 2016. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 65, 1015–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuramoto SJ, Bohnert AS, Latkin CA, 2011. Understanding subtypes of inner-city drug users with a latent class approach. Drug Alcohol Depend. 118, 237–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lokala UL, Lamy FR, Daniulaityte R, Sheth A, Nahhas RW, Roden JI, Yadav S, Carlson RG 2018. Global trends, local harms: availability of fentanyl-type drugs on the dark web and accidental overdoses in Ohio. Comput. Math. Organ. Theory 10.1007/s10588-018-09283-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mars SG, Ondocsin J, Ciccarone D, 2018. Sold as heroin: Perceptions and use of an evolving drug in Baltimore, MD. J. Psychoactive Drugs 50, 167–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Drug Early Warning System, (NDEWS), 2015. Fentanyl and fentanyl analogs. NDEWS Special Report. https://ndews.umd.edu/resources/fentanyl [Google Scholar]

- National Drug Early Warning System, (NDEWS), 2017. Highlights from the NDEWS New Hampshire HotSpot study. https://ndews.umd.edu/sites/ndews.umd.edu/files/ndews-highlights-new-hampshire-hotspot-study-final.pdf [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell JK, Halpin J, Mattson CL, Goldberger BA, Gladden RM, 2017. Deaths involving fentanyl, fentanyl analogs, and U-47700 – 10 states, July-December 2016. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 66, 1197–1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohio Department of Health, 2017a., 2016 Ohio drug overdose data: General findings. https://www.odh.ohio.gov/en/features/2018/ODH-2017-Ohio-Drug-Overdose-Report

- Ohio Department of Health, 2017b. Combatting the opioid crisis in Ohio. https://mha.ohio.gov/Portals/0/assets/Initiatives/GCOAT/Combatting-the-Opiate-Crisis.pdf

- Peiper NC, Clarke SD, Vincent LB, Ciccarone D, Kral AH, Zibbell JE, 2019. Fentanyl test strips as an opioid overdose prevention strategy: Findings from a syringe services program in the Southeastern United States. Int. J. Drug Policy 63, 122–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson AB, Gladden RM, Delcher C, Spies E, Garcia-Williams A, Wang Y, Halpin J, Zibbell J, McCarty CL, DeFiore-Hyrmer J, DiOrio M, Goldberger BA, 2016. Increases in fentanyl-related overdose deaths - Florida and Ohio, 2013–2015. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 65, 844–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L, 2016. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths - United States, 2010–2015. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 65, 1445–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavova S, Costich JF, Bunn TL, Luu H, Singleton M, Hargrove SL, Triplett JS, Quesinberry D, Ralston W, Ingram V, 2017. Heroin and fentanyl overdoses in Kentucky: Epidemiology and surveillance. Int. J. Drug Policy 46, 120–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville NJ, O’Donnell J, Gladden RM, Zibbell JE, Green TC, Younkin M, Ruiz S, Babakhanlou-Chase H, Chan M, Callis BP, Kuramoto-Crawford J, Nields HM, Walley AY, 2017. Characteristics of fentanyl overdose - Massachusetts, 2014–2016. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 66, 382–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strayer KE, Antonides HM, Juhascik MP, Daniulaityte R, Sizemore IE, 2018. LCMS/MS-based method for the multiplex detection of 24 fentanyl analogues and metabolites in whole blood at sub ng mL(-1) concentrations. ACS Omega 3, 514–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki J, El-Haddad S, 2017. A review: Fentanyl and non-pharmaceutical fentanyls. Drug Alcohol Depend. 171, 107–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomassoni AJ, Hawk KF, Jubanyik K, Nogee DP, Durant T, Lynch KL, Patel R, Dinh D, Ulrich A, D’Onofrio G, 2017. Multiple fentanyl overdoses - New Haven, Connecticut, June 23, 2016. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 66, 107–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]