Abstract

Unraveling the complex behavior of healthy and disease podocytes by analyzing the changes in their unique arrangement of foot processes, slit diaphragm, and the three-dimensional (3D) morphology is a long-standing goal in kidney–glomerular research. The complexities surrounding the podocytes' accessibility in animal models and growing evidence of differences between humans and animal systems have compelled researchers to look for alternate approaches to study podocyte behaviors. With the advent of bioengineered models, an increasingly powerful and diverse set of tools is available to develop novel podocyte culture systems. This review discusses the pertinence of various culture models of podocytes to study podocyte mechanisms in both normal physiology and disease conditions. While no one in vitro system comprehensively recapitulates podocytes' in vivo architecture, we emphasize how the existing systems can be exploited to answer targeted questions on podocyte structure and function. We highlight the distinct advantages and limitations of using these models to study podocyte behaviors and screen therapeutics. Finally, we discuss various considerations and potential engineering strategies for developing next-generation complex 3D culture models for studying podocyte behaviors in vitro.

Impact Statement

In various glomerular kidney diseases, there are numerous alterations in podocyte structure and function. Yet, many of these disease events and the required targeted therapies remain unknown, resulting in nonspecific treatments. The scientific and clinical communities actively search for new modes to develop structurally and functionally relevant podocyte culture systems to gain insights into various diseases and develop therapeutics. Current in vitro systems help in some ways but are not sufficient. A deeper understanding of these previous approaches is essential to advance the field, and importantly, bioengineering strategies can contribute a unique toolbox to establish next-generation podocyte systems.

Keywords: podocytes, glomeruli, kidney disease, tissue engineering, in vitro models, 3D culture

Introduction

The need for novel human-based bioengineered podocyte culture systems is important due to a paucity of predictive human models and an ineffective drug-development pipeline for glomerular diseases.1,2 Traditionally, animal models have been used as an experimental tool for podocyte research. Such models have direct physiological relevance and can recapitulate key disease features. However, examining the changes associated with podocyte maturation or glomerular disease progression remains challenging due to their complex location.3,4 Furthermore, animal models can differ from human conditions in key ways (e.g., mice lack the APOL1 gene, a critical mediator of multiple human glomerular diseases).5

Alternatively, in vitro two-dimensional (2D) systems have been widely used to study the mechanisms surrounding podocyte behaviors. This concept of studying podocytes in an in vitro setup was first formally attempted more than 40 years ago by treating kidney slice models with different chemical agents.6 Thanks to the advances in cell culturing, multiple in vitro podocyte culture approaches have been developed since then.7 These 2D systems, including explant tissues and glomerular outgrown podocytes, provide an easy-to-edit platform and are amenable to perform various types of molecular analyses. However, the 2D culture conditions are artificial and do not recapitulate podocytes' in vivo features or dynamic fluidic conditions.

In response to these limitations, multiple bioengineered systems with some level of in vivo complexity and dynamic fluid control have been developed.8–10 This review discusses the features of such bioengineered systems and highlights how they can be used to study podocyte morphology and function in different conditions. Given that the use of three-dimensional (3D) tissue systems spanning the entire kidney (e.g., organoids) has been reviewed previously elsewhere,11,12 we focus here on the systems that are targeted for podocyte studies. While it is widely recognized that none of the existing in vitro systems truly recapitulate the unique 3D structural features of podocytes, we describe how the existing simplified systems can be exploited to understand targeted questions related to podocyte architecture and behavior. We comparatively discuss the advantages and limitations of studying podocytes in these systems over other traditional systems. Moreover, we then highlight how one can exploit the recent advances in biomaterials and tissue engineering to build more complex systems and improve their relevance to in vivo podocyte architecture and behavior.

We present this review by beginning with an overview of glomerular development, focusing on podocyte structure. We highlight the sequential changes leading to podocyte unique morphology and arrangement within glomeruli. Next, we discuss the different engineered systems of podocyte cultures, ranging from simple Transwell cell systems to organ-on-chip systems. In doing so, we provide specific examples to highlight their unique advantages and relevance to in vivo podocytes. Finally, we outline new technologies that can be integrated with these systems to improve the podocyte culture relevancy and program next-generation podocyte culture systems.

In Vivo Glomerular Development and Podocyte Maturation

The glomerulus is the most proximal structure of nephrons. Their presence within a developing kidney can first be distinctly appreciated by a precursor structure called an “S-shaped body.”13–16 At this stage, three distinct components can be associated with the developing glomeruli:

A capillary loop that enters the glomerular cleft;

A layer of columnar epithelium, which later matures as podocytes;

A layer of the Bowman capsule, which appears as a flat squamous epithelial layer.

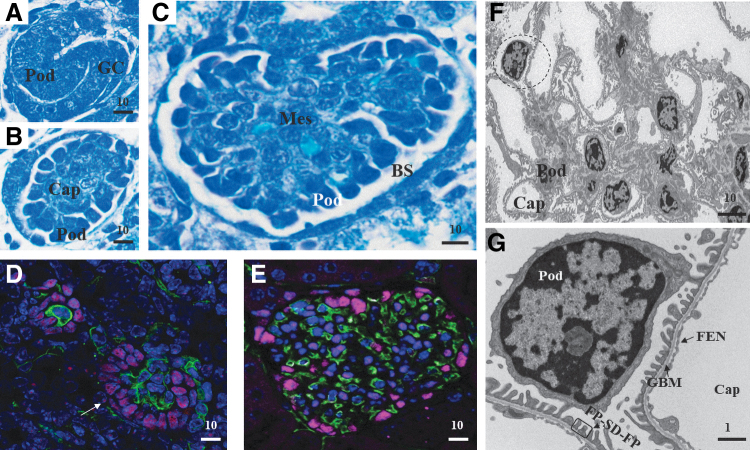

As the structure continues to mature, the podocytes extend around the capillary loop and come adjacent to endothelial cells. Subsequently, these endothelial cells and podocytes secrete the basal lamina that fuses to form a glomerular basement membrane (GBM) between them.13,17,18 Concurrent with this GBM formation, the podocytes undergo a remarkable transformation and acquire some mesenchymal-like features such as loss of lateral adhesion and isolation from other podocyte cell bodies. Finally, the podocytes mature with several large extensions called primary processes, which branch into intermediate secondary processes that further branch into many smaller tertiary processes called “foot processes.” The foot process structures interdigitate with adjacent podocytes' foot processes to form a specialized cell–cell junction called the slit diaphragm. These final matured foot process structures range with a median distance of ∼250 nm between adjacent foot processes (human),15,19 thus limiting the analysis options to either electron microscopy or super-resolution microscopy.20 Figure 1 shows a developing glomerulus, highlighting the arrangement of podocytes at different stages.

FIG. 1.

Glomerular development and podocyte maturation. (A–C) Toluidine blue-stained sections from newborn mouse glomerulus. (A) S-shaped body. (B) Glomerulus with immature podocytes and capillary loops. (C) Matured glomerulus. (D, E) Immunofluorescence staining of podocytes and capillary in glomeruli. Purple, WT-1, podocytes; green, endomucin, endothelial cells; blue, DAPI, nuclei. (D) Immatured glomerulus showing the “bowl” shaped arrangement of podocytes (white arrow). (E) Matured glomerulus with podocyte arrangement in the Bowman space. Image in (E) kindly provided by Lena Schaller (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA). (F) Transmission electron micrograph of a mouse glomerulus. (G) The magnified region from panel (F). All scale bar in micron units. BS, Bowman's space; Cap, capillary; FEN, fenestrated endothelium; FP, foot processes; GBM, glomerular basement membrane; GC, glomerular cleft with precursor endothelial cells; Mes, mesangial cells; Pod, podocytes; SD, slit diaphragm. Color images are available online.

The formation of interdigitating foot processes and the slit diaphragm is a unique aspect of podocyte maturation. This structural maturation of podocytes is essential for mediating normal glomerular function. Although the precise molecular mechanisms by which podocytes establish this elaborate and unique organization are unknown, the appearance suggests a sequential process involving cell-body polarization and extension of the processes to envelop the capillaries.21,22 At present, there is little understanding of how these events occur. Existing studies on in vivo models suggest that the organization is largely dependent on the spatial and temporal regulation of the underlying higher order actin organization.23

Complexities surrounding podocyte accessibility and analysis

A key factor that limits the analysis of podocytes is their complex location within the kidney and our inability to access them for analysis. In a typical kidney, the podocytes constitute less than 1% of the total kidney cell population. Current research strategies have often used glomerular extraction procedures to collect and concentrate the podocyte in the research samples.24 While this strategy allows podocyte enrichment, the underlying steps in glomerular preparation, such as collagenase digestion, are harsh and can cause artifacts. Furthermore, batch-to-batch variations between glomerular preparations can cause heterogeneity in data collection and interpretation.

Similar complexities surround the podocyte-imaging approaches as well. For example, the standard fixation methods do not diffuse deep enough into the kidney, causing distortions in podocyte structures. Therefore, perfusion fixation via the vascular system is the only option to fix podocytes properly.24 In addition, the podocyte location within the Bowman space requires long-range working lenses or deep imaging methods such as multiphoton microscopy to reach them for imaging.25,26 Finally, the nanoscale unique structures of podocytes, including foot process and slit diaphragms, limit their imaging options to either electron microscopy or super-resolution microscopy.20 Thus, studying in vitro is the only way to dissect and analyze the cellular and molecular events associated with podocyte behaviors. However, current models lack the podocytes' unique morphology, including the foot process and slit diaphragm structures. Thus, the systems need an improvising in the design to improve their performance.

Bioengineered Podocyte Culture Systems

Bioengineered culture systems, in general, are in vitro culture models that are reverse engineered to recapitulate critical structural and functional aspects of specific organs and tissues. While there is a vast diversity in the design of 3D tissue models in general, bioengineered podocyte culture systems are relatively few ranging from models that are as simple as the podocytes–endothelial co-cultures grown as 2D Transwell cultures to complex microfluidic platforms. All these systems have one defining feature that differentiates them from a typical 2D system: the presence of signaling cues relevant to the podocyte microenvironment (e.g., hemodynamic shear stress due to fluid flow or stretch forces imposed via endothelial cell curvature).

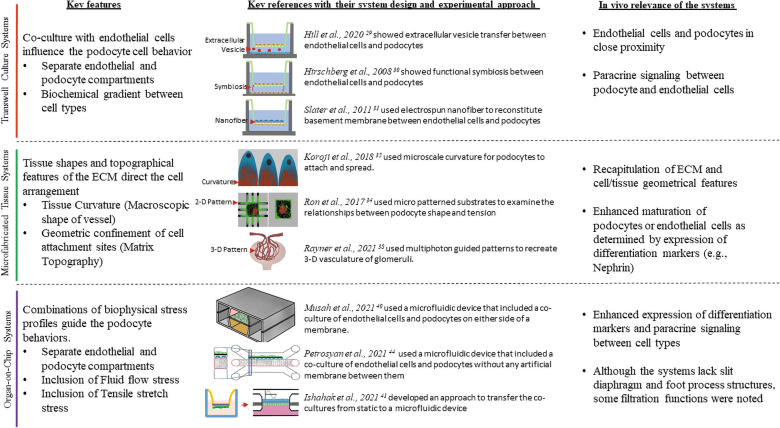

To date, a bioengineered system that replicates in vivo endothelial–GBM–podocyte arrangement with their unique structural features has not been achieved. However, multiple simplistic models have been developed that can be used to investigate targeted podocyte behavioral questions. Figure 2 illustrates the different groups of bioengineered podocyte culture systems and highlights how they can be useful to assess a specific podocyte feature. A key advantage of these simplistic models is that they provide enormous flexibility compared with animal models to perturb and examine various podocyte-related biological processes. Also, it allows for easy and rapid screening of multiple properties, such as functional effects of genetic variants, along with multiple conditions, such as fluid flow rate and pressure, in an appropriate and controlled environment.

FIG. 2.

Current bioengineered platforms to study podocyte behaviors. The different systems are grouped into three categories, and their key features are highlighted. Color images are available online.

Recently, kidney organoids have also been developed and used for various applications.27 Table 1 shows some key features of 2D cultures, organoids, and bioengineered systems of podocytes and highlights how they differ from each other. Each of these platforms has both relevant and artificial features. However, we have not categorized the kidney organoids as a bioengineered system and did not include them in this review because their development is driven by stochastic self-assembly. Additionally, they lack control of various parameters such as tissue dimensions, diversity, and overall cytoarchitecture.28 Finally, the resulting tissue mass format and shape are often difficult to analyze for functional parameters such as filtration properties. Unlike kidney organoids, bioengineered systems are developed by programmed scaffolding or cell seeding to reconstitute key glomerular features and allow probing of cell parameters and tissue functional parameters. Thus, the systems' design and the resulting biological output are controlled by the underlying engineering means. In the following subsections, we describe the usability of bioengineered systems to study structural and functional aspects of podocytes and examine their relevance with known in vivo podocyte behaviors.

Table 1.

Summary of Key Features, Advantages, Disadvantages, and In Vivo Relevance of Different Podocyte Culture Systems

| Parameter | 2D podocyte cultures | Bioengineered podocyte culture systems | Podocytes in kidney organoids | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| System features | Cell growth pattern | Grown as a monolayer on cell culture plastics | Seeded on to engineered substrates. Biomechanical forces and fluid flow perfusion may be included as per system design | Suspended as cell pellet and allowed to self-organize to form kidney organoids with podocytes |

| System maturation time | Few minutes to few days | Variable time and depends on the platform's design—usually intermediate between 2D systems and organoids | Longer time frames (multiple weeks) | |

| Level of control on the organization | High | High | Very low | |

| Vascular perfusion compatibility | Not feasible | Either via created endothelial vessels or direct microfluidics | Lacks control over vasculature, but feasible to externally perfuse the structures | |

| High-throughput extension | Readily feasible | Can attain low–medium throughput with some platform design | Possible without perfusion | |

| Assay feasibilities | Readily feasible for a wide range of assays in real time | Real-time cell type-specific analysis feasible | Tissue analysis is feasible, but the cell type analysis is complex | |

| In vivo relevance | Structural organization | Unnatural monolayer growth and lack relevant structures | Improved structures with options to enable the 3D arrangement with endothelial cells | Immatured and clustered |

| Functional performance | No options to test functionality | Options to perform filtration functions are available | Lacks vascularization to perform functions |

2D, two-dimensional; 3D, three-dimensional.

Transwell culture systems

Transwell cultures are systems that include a filter insert to support cell adhesion. They are often used for establishing co-cultures by culturing different cell types on either side of the filter or culturing one cell type on the filter and the other on the lower chamber. Podocytes have been studied with endothelial cells in Transwell systems to understand how they influence each other.29–32 For example, Hirschberg et al. used Transwell systems and showed that podocyte secretions such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) could influence the endothelial cells' cord formation.30 A key advantage in using these systems is that they reconstitute the podocytes adjacent to the endothelial cells. However, the systems do not induce any in vivo-relevant subcellular features, such as foot processes in podocytes.

Another benefit of the Transwell systems is that it allows independent access to both sides of the filter insert, thus feasible to perform studies on cell type-specific transport, filtration, and metabolic activities. However, these systems remain minimally explored in those avenues. The modest reception of these systems to study various podocyte behaviors can be attributable to factors such as the lack of in vivo relevant extracellular matrix (ECM), tissue shape and geometry (e.g., cylindrical shape of the endothelial vessel), and biophysical profiles (e.g., fluid flow) in the system setup. In addition, the advent of more complex systems with a better recapitulation of glomerular features has advanced the field forward. Nevertheless, the Transwell systems remain as an easy-to-use system, particularly for studies on paracrine signaling between endothelial cells and podocytes.

Microfabricated systems

Microfabricated systems are culture systems that enable control over the spatial organization of cells. Typically, they use micropatterned or micro molded substrates to guide the cells to reach a specific geometry and form. One primary advantage of using these systems is that the cells exhibit in vivo-relevant organization with minimal heterogeneity33; thus, examining the phenotypic differences is much easier than in 2D systems. In addition, programming options at the ECM level can allow studies on assessing how the different physical and chemical properties of the ECM can affect cell behaviors.33 Such studies can inform us on future protocols to rationally program biomaterials and ECM properties to replicate the microenvironment of the in vivo tissue.

Multiple studies have used microfabricated 2D systems to study podocytes. For example, Ron et al. used micropatterned cells to examine the mechanisms determining the cell shape.34 Another recent study developed a curved substratum to mimic endothelial cells' curvature and used them to culture podocytes.35 The substrate curvature improved the localization of key-podocyte proteins, including Nephrin. A key advantage in using these 2D microfabricated systems is that they can be readily scaled up to a high-throughput configuration, thus providing large sample sizes to establish statistical significance. However, the lack of perfusing vascular channels limits their utility to study podocytes' structural properties, but not in vivo filtration functions. In addition, the 2D configuration of these systems does not allow assessing the interactions between podocytes and endothelial cells.

To date, there is no 3D microfabricated tissue model that recapitulates podocyte in vivo arrangement. This is attributed mainly to the hurdles in replicating the in vivo arrangement of podocytes and endothelial cells. For example, currently available 3D microfabrication approaches, including lithography and bioprinting, can generate tissues in the order of a few hundred microns.36,37 These ranges are relatively larger than the glomerular capillary geometries. Thus, it can be challenging to generate capillary-scale tissues. Recently, Rayner et al. used multiphoton-guided microvasculature in 3D.38 These structures are in the scale of capillaries and can be perfused. However, it remains unclear if this can be adapted for co-cultures, particularly to replicate podocytes' position in the Bowman space. Thus, a revamped strategy is needed to reconstitute podocyte–endothelial arrangement as in vivo. We believe that such a system can provide critical insights into the mechanisms that govern podocyte morphology and their intracellular organization, including the actin arrangement.

Microfluidic organ-on-chip systems

Organ-on-chips are the most advanced in vitro systems available to date to study cell behaviors. These systems include microfluidic flow and are usually designed in a modular manner to connect with other organ-on-chip systems. They can provide controlled pressure and flow, relatively high throughput, and are compatible with various assays, thus indicating great potential for creating and analyzing multiple tissue models.39 Although the tools have not necessarily been applied to the glomerulus, a few glom-on-chip systems have been developed and used some of these tools and used the systems for podocyte research studies. For example, the chip model developed by Musah et al. comprises human podocytes and endothelial cells cultured as monolayer cells on opposite sides of a semipermeable membrane.40 In a similar cell arrangement but in a polydimethylsiloxane-free setup, Ishahak et al. cultured podocytes and recapitulated the barrier function of podocytes.41 More recently, by taking inspiration from the bulk glomerular morphology, Xie et al. developed a hollow fiber-based glomerulus knot model with the microfluidic flow.42 Here, the podocytes were cultured to cover a hydrogel-based knot's surface and then subsequently examined for their structure and function. Besides these generic podocyte analytical systems, disease-specific models have also been developed in organ-on-chips configurations. For example, Wang et al. developed a chip device for modeling diabetic nephropathy.43 The system aided in understanding the effect of high glucose on glomerular and podocytes structure in a native tissue arrangement. In another study, Petrosyan et al. used a platform developed by Mimetas, Inc., and examined the podocyte filtration barrier alterations when exposed to various kidney disease patient sera.44

These proof-of-concept studies showed that the chip systems are helpful to assess the filtration properties of podocytes that are otherwise difficult to examine in 2D or in vivo conditions. In addition, the systems can be exploited to evaluate a wide range of processes, such as the endothelial cells and podocyte interactions and podocyte actin arrangement. However, these systems do have their share of limitations as well. First, when compared with Transwell cultures, there is not much improvising in the ECM component of the organ-on-chip systems. Most of the systems employ porous membrane filters to co-culture monolayers of podocytes and endothelial cells. This arrangement in organ-on-chips is similar to Transwell systems. Second, none of the current organ-on-chip systems recapitulates the native tissue shape and the governing ECM configurations in their design. This compromise in the system design limits in vivo relevance and does not allow studying tissue-level behaviors. Third, the lack of interdigitating foot process and slit diaphragm structures raises skepticism on whether the noted filtration functions in the organ-on-chip systems are relevant to slit diaphragm-dependent in vivo filtration. Finally, there is no consensus in the underlying parameters between different systems. For example, the parameters, such as cell types, tissue geometry, perfusion medium, and fluid flow rate, are different between systems, limiting their adaptability for various assays and broad acceptance into the research community.

Strategies to Develop the Next-Generation Podocyte Culture Systems

Although bioengineering tools have improved our capacity to examine the podocytes in vitro, the complexity of podocyte structure requires a continuum of model systems with improved biological and biophysical relevance. In the following sections, we discuss the podocyte-specific design considerations critical for improving the in vivo relevance of the model systems. We discuss them in the context of available technologies and the challenges in adapting them to match the podocyte-specific features. We finally propose strategies that may help achieve the in vivo relevance and desired outcomes.

Considerations to improve biological relevance

Cells

A common challenge faced in podocyte research is cell sourcing. To date, at least three types have been used for podocyte sourcing: primary cells (e.g., Celprogen, Inc.), established cell lines (e.g., Saleem et al.45), and derivations from induced pluripotent stem cells (IPSCs).40,45,46 While none of these sources exhibits a truly matured phenotype as in vivo podocytes, increasingly, IPSCs are seen as the answer to invest and source for podocytes. This is due to several compelling advantages that the IPSC can offer: IPSCs provide unlimited renewable sources and differentiate to multiple cell types. Thus, to develop a multi-cell type system, all the different cell types can be derived from a single parental IPSC line. Furthermore, they can be coupled with the recent advances in synthetic biology and CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing technologies to program genetically defined phenotypes along with their matched isogenic controls for comparative analysis.47,48

However, IPSC has its limitations as well. First, the existing differentiation protocols of podocytes are long and do not yield a mature phenotype. Second, the residual epigenetic memory of somatic cells from which IPSCs were derived may influence phenotype development in disease modeling or alter therapeutic responses. Third, the embryonic nature of IPSCs and their derivative may not be optimal to replicate cellular aging and to study late-onset diseases. In contrast, primary podocytes or established cell lines, despite their caveats, can avoid some of these limitations. Also, from a practical standpoint, evaluation using established cells is relatively less time-consuming and lighter on consumable cost. Thus, model design and usage context need to be considered before the cell-source selection.

Extracellular matrix

Another evident issue is the lack of an appropriate 3D matrix environment. Current systems have relied mainly on purified ECM proteins such as collagen I, laminin, reconstituted basement membrane such as Matrigel, or their derivatives, to support podocyte cultures in various systems.40,49 However, the composition and organization of the GBM to which the podocytes are attached are unique and different from these standard-ECM choices. A relevant approach to address this problem will be to use the ECM components derived from glomeruli. The decellularization procedures for tissues and organs, including kidneys, remove cells while preserving the ECM structure and composition. This approach has been used to derive tissue-specific ECM such as mammary glands.50–52 A similar strategy can be adapted to derive glomeruli-specific ECM to support podocyte cultures. Alternatively, one could allow the cells to synthesize their matrix in cultures. However, this will require more extended periods and optimization, which may cause variations in assay outcomes.

A further challenge exists in developing the in vivo arrangement of podocytes with endothelial vessels. Podocytes are positioned in the urinary space, and their attachment is limited to the basal side. The presence of space on the apical side of the podocytes facilitates the filtrate to flow to the subsequent tubular segments. In contrast, endothelial vessels are usually developed by embedding endothelial cells in the hydrogels.53 Therefore, including the podocytes with endothelial tubes will not reconstitute the urinary space for the filtrate to flow. Thus, building a system with the in vivo-like arrangement of podocytes in the urinary space is complex and poses a unique challenge to develop using existing tools and technologies.

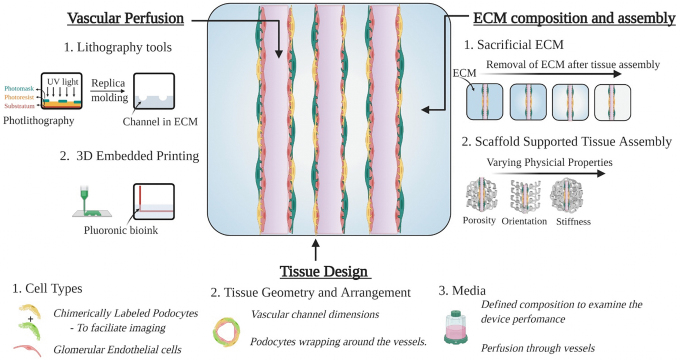

Recent advances in biomaterials research have opened new opportunities that can be explored to achieve these unique features in the culture systems. For example, Miller et al. developed a carbohydrate-based sacrificial matrix for guiding vessel formation. Here, the glass matrix was used to create a channel in a hydrogel, and later, the matrix was sacrificed to form hollow tubes.54 Similar approaches were used in bioprinting with fugitive inks.36 This method of sacrificing the material at a later stage can be adapted to generate the podocyte–endothelial arrangement with urinary space. Here, after podocyte attachment to endothelial tubes, we could sacrifice the surrounding matrix to create the urinary space. Alternatively, approaches that allow the generation of free-standing channels have been described with various biomaterials.55 One could use those methods and culture endothelial cells and podocytes at the inner and outer surfaces. However, the properties of biomaterials, such as thickness, porosity, and compatibility, will all influence cell behaviors.

Media composition

Finally, a key challenge for podocyte culturing is selecting the suitable media composition. It is believed that podocytes' exposure to serum components in vivo is limited to the biochemical factors that cross the GBM. Complete knowledge of these components remains unknown. However, prior studies have indicated that paracrine signaling (e.g., VEGF) exists between endothelial cells and podocytes.18,56 Thus, the full range of biochemical factors needed for podocyte media remains unclear.

Nevertheless, most studies have taken a generic approach and included high concentrations of serum. For example, cell line-based studies have widely used an Roswell Park Memorial Institute-based medium with high serum.45 While these studies have helped identify key podocyte features, our opinion is that the use of high serum for podocyte assay conditions should be revisited. We believe that it would be appropriate to start with a basal medium and add-on supplements that support cell viability and maturation. This approach will allow the inclusion of components necessary for other cell types and tissues, thus enabling co-culture and integration with other tissue systems (e.g., tubule systems).

Considerations to improve biophysical relevance

Previous studies have shown that when podocytes and endothelial cells are co-cultured without any biophysical cues, they coalesce into a disorganized cell cluster.57 This suggests that extrinsic guidance is necessary to guide the cell interactions to establish an appropriate in vivo-like arrangement. However, there are challenges in recapitulating the biophysical stress profiles in podocyte culture systems. First, it remains unclear what type of stress profiles are needed for the podocyte systems. Next, how should they be integrated without compromising the podocyte in vivo arrangement and function?

Inclusion of biophysical stress types

The biophysical stress experienced by podocytes can be either passive or active.58 Signals from ECM topography, stiffness, and geometrical confinement contribute to the passive forms, whereas the fluid flow shear stress, pressure-induced normal stress, tensile stretch, and compression contribute to the active forms of stress.58 To include all these stress profiles in the tissue systems will be ideal; however, systems with simplified biophysical stress profiles can also be useful. In such cases, the research question should be used as a guide to determine the choice and level of biophysical complexity. For example, if the goal is to examine filtration, the system should include hemodynamic stress. However, if accompanying podocyte structure changes are needed, the systems should include other stress types such as ECM stiffness and topography as well. Thus, caution is warranted while analyzing with simplified systems; particularly, the data interpretation should not be stretched beyond the systems' in vivo relevance. In addition, wherever possible, further data validation is recommended to conclude on the findings on podocyte behaviors.

Specifics of biophysical stress

The final cellular response to various biophysical stress types is largely dependent on stress specifics' such as duration, magnitude, direction relative to the cell layer, and frequency. Therefore, various stress specifics, including seeding density, cell-type ratios, ECM composition, and flow rate and pressure, should be programmed to match the glomerular conditions. However, a lot of this knowledge is unknown, limiting our ability to program the specifics of various biophysical stresses.

Existing studies on in vivo glomeruli provide some clues to derive these specifics. For example, intravital imaging of in vivo glomeruli has indicated that normal and disease podocytes differ in shape and motility. The normal podocytes are nonmotile and maintain a canopy-shaped structure, whereas the injured cells often retract processes.26 These observations suggest that the podocyte culture systems should be replicating similar nonmotile arrangements in normal conditions and transform to an altered phenotype with injury events. In addition, the fluid flow-induced stretch on vessel-shaped endothelial cells will be more relevant than stretch stress applied directly over the podocytes or endothelial monolayers.

Similarly, clues from in vitro podocyte studies can be used as guidance to determine the specifics of biophysical stress. For example, in one study, Abdallah et al. used polyacrylamide hydrogels with varying stiffness and assessed how podocytes respond to different stiffness. The results showed that podocytes on softer hydrogels exhibited improved adhesion, marker-protein expression, and formed foot process-like structures.59 This suggests that softer ECM in the physiological range may be optimal to use instead of a stiffer substratum, such as membrane filters. Thus, in similar ways, specifics of the various biophysical stress types, including ECM composition, and the flow rate, can be derived from either the fundamental in vivo studies or the in vitro podocyte analysis. Future studies can adapt these approaches and refine the protocols to establish optimal assay conditions for applying biophysical cues to podocytes in culture systems.

Next-Generation Systems

The next-generation systems can leverage the platforms created so far and advance toward developing an ideal podocyte culture system with its unique features. We believe that combining the concepts of tissue engineering and organs-on-chips can provide novel strategies to match the needs of an ideal podocyte culture system. The integration of concepts from both these strategies can produce systems that include different biophysical stress types as well as provide necessary guidance for podocyte–endothelial interaction. Typically, tissue engineering approaches employ scaffolds (e.g., silk fibroin scaffolds) in various configurations to develop tissue mimetics.60 Here, the scaffold configurations can be tailored to support the arrangement of cells and provide a framework to recapitulate the various biophysical cues of glomerular tissues. As outlined in Figure 3, a porous scaffold with perfusable channels can be used to develop a relevant podocyte system. The perfusable channels support endothelial vessel development, whereas the open porous structure allows for podocyte addition. The porous space can also serve as a urinary space for filtrate collection. Thus, this configuration can guide in vivo-like arrangements and simulate various biophysical stress profiles experienced by podocytes.

FIG. 3.

Bioengineering next-generation podocyte culture systems. Composite image of various design considerations for podocyte culture systems. Three key components, including vascular perfusion, tissue design, and ECM arrangement, are highlighted. In addition, specific examples of tools or approaches that could potentially be used to replicate the unique features of podocytes into an in vitro system are provided. ECM, extracellular matrix. Color images are available online.

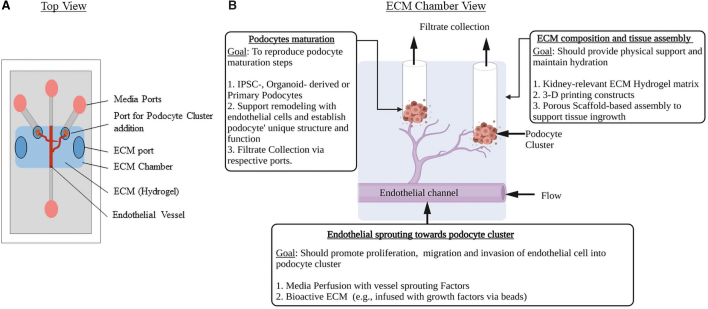

Alternatively, the steps in glomerular development can be reconstructed in an organ-on-chip. As outlined in Figure 4, a podocyte cell cluster next to a perfusable endothelial vessel can be built in a chip. With the subsequent addition of sprouting signals,61 the vascular channel can be induced to branch and invade podocytes. We believe that this configuration would replicate the early stages of glomerular development, and with sustained perfusion, one can follow the events in glomerular development and maturation.

FIG. 4.

An organ-on-chip design to replicate the glomerular development and podocyte maturation steps. (A) Top view. (B) ECM chamber view. Design considerations to attain in vivo relevance have been highlighted: ECM configurations (e.g., stiffness, composition) that match the in vivo features can be used as hydrogels. Multiple cell sources can be tested and optimized. Specific cues to guide the vessels to branch and invade the podocyte cluster could be delivered via media or the ECM hydrogel. Color images are available online.

Conclusions

The biological alternative to the animal models and the 2D culture systems has become an inevitable need for studying podocyte behaviors. Recently, considerable momentum exists in developing novel bioengineered podocyte culture systems and reinventing methods to study podocyte behaviors in vitro. However, different parameters, including ECM composition and configuration, cell types, and biophysical parameters, must be carefully considered and optimized before these new technological platforms are introduced for any translational efforts. Ultimately, recapitulating the features of podocyte structure and function will be crucial for the wide adoption of those bioengineered systems. Finally, the arrival of an optimal bioengineered podocyte system with the relevant biophysical cues, structural and functional features, and options to scale up can effectively bridge the gap between 2D and animal models. In addition, such systems will also inform us on future protocols for developing novel devices to support kidney filtration function in patients.

Acknowledgment

The authors used BioRender software for preparing graphics.

Authors' Contributions

S.W. and B.S. conceptualized, wrote, and reviewed the article. J.L.C. and M.R.P. reviewed and edited the article.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This work was supported by funds from the Peer Reviewed Medical Research Program (PRMRP)-Department of Defense (DoD) (Grant No. W81XWH2010320) and the National Institutes of Health (Grant No. RC2 DK122397).

References

- 1. Edmonston, D.L., Roe, M.T., Block, G., et al. Drug development in kidney disease: proceedings from a multistakeholder conference. Am J Kidney Dis 76, 842, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Progress, M., Kaskel, F.J., Falk, R.J., et al. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. N Engl J Med 365, 2398, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Becker, G.J., and Hewitson, T.D.. Animal models of chronic kidney disease: useful but not perfect. Nephrol Dial Transplant 28, 2432, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yang, H.-C., Zuo, Y., and Fogo, A.B.. Models of chronic kidney disease. Drug Discov Today Dis Model 7, 13, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Genovese, G., Friedman, D.J., Ross, M.D., et al. Association of trypanolytic ApoL1 variants with kidney disease in African Americans. Science 329, 841, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Andrews, P.M. Investigations of cytoplasmic contractile and cytoskeletal elements in the kidney glomerulus. Kidney Int 20, 549, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shankland, S.J., Pippin, J.W., Reiser, J., and Mundel, P.. Podocytes in culture: past, present, and future. Kidney Int 72, 26, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Benam, K.H., Dauth, S., Hassell, B., et al. Engineered in vitro disease models. Annu Rev Pathol Mech Dis 10, 195, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rimann, M., and Graf-Hausner, U.. Synthetic 3D multicellular systems for drug development. Curr Opin Biotechnol 23, 803, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Breslin, S., and O'Driscoll, L.. Three-dimensional cell culture: the missing link in drug discovery. Drug Discov Today 18, 240, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Romero-Guevara, R., Ioannides, A., and Xinaris, C.. Kidney organoids as disease models: strengths, weaknesses and perspectives. Front Physiol 11, 1, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rooney, K.M., Woolf, A.S., and Kimber, S.J.. Towards modelling genetic kidney diseases with human pluripotent stem cells. Nephron 145, 285, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vaughan, M.R., and Quaggin, S.E.. How do mesangial and endothelial cells form the glomerular tuft? J Am Soc Nephrol 19, 24, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Haraldsson, B., Nystrom, J., and Deen, W.M.. Properties of the glomerular barrier and mechanisms of proteinuria. Physiol Rev 88, 451, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Garg, P. A review of podocyte biology. Am J Nephrol 47, 3, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Quaggin, S.E., and Kreidberg, J.A.. Development of the renal glomerulus: good neighbors and good fences. Development 135, 609, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kikkawa, Y., Virtanen, I., and Miner, J.H.. Mesangial cells organize the glomerular capillaries by adhering to the G domain of laminin α5 in the glomerular basement membrane. J Cell Biol 161, 187, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lindahl, P., Hellström, M., Kalén, M., et al. Paracrine PDGF-B/PDGF-Rbeta signaling controls mesangial cell development in kidney glomeruli. Development 125, 3313, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Siegerist, F., Ribback, S., Dombrowski, F., et al. Structured illumination microscopy and automatized image processing as a rapid diagnostic tool for podocyte effacement. Sci Rep 7, 1, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Siegerist, F., Endlich, K., and Endlich, N.. Novel microscopic techniques for podocyte research. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 9, 1, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Little, M., Georgas, K., Pennisi, D., and Wilkinson, L.. Kidney development: two tales of tubulogenesis. Curr Top Dev Biol 90, 193, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fanos, V., Loddo, C., Puddu, M., et al. From ureteric bud to the first glomeruli: genes, mediators, kidney alterations. Int Urol Nephrol 47, 109, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Perico, L., Conti, S., Benigni, A., and Remuzzi, G.. Podocyte-actin dynamics in health and disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 12, 692, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Subramanian, B., Sun, H., Yan, P., et al. Mice with mutant Inf2 show impaired podocyte and slit diaphragm integrity in response to protamine-induced kidney injury. Kidney Int 90, 363, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Angelotti, M.L., Antonelli, G., Conte, C., and Romagnani, P.. Imaging the kidney: from light to super-resolution microscopy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 36, 19, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brähler, S., Yu, H., Suleiman, H., et al. Intravital and kidney slice imaging of podocyte membrane dynamics. J Am Soc Nephrol 27, 3285, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Takasato, M., Er, P.X., Chiu, H.S., et al. Kidney organoids from human iPS cells contain multiple lineages and model human nephrogenesis. Nature 526, 564, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Takasato, M., Er, P.X., Chiu, H.S., and Little, M.H.. Generation of kidney organoids from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Protoc 11, 1681, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hill, N., Michell, D.L., Ramirez-Solano, M., et al. Glomerular endothelial derived vesicles mediate podocyte dysfunction: a potential role for miRNA. PLoS One 15, 1, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hirschberg, R., Wang, S., and Mitu, G.M.. Functional symbiosis between endothelium and epithelial cells in glomeruli. Cell Tissue Res 331, 485, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Slater, S.C., Beachley, V., Hayes, T., et al. An in vitro model of the glomerular capillary wall using electrospun collagen nanofibres in a bioartificial composite basement membrane. PLoS One 6, e20802, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Casalena, G.A., Yu, L., Gil, R., et al. The diabetic microenvironment causes mitochondrial oxidative stress in glomerular endothelial cells and pathological crosstalk with podocytes. Cell Commun Signal 18, 1, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Subramanian, B., Kaya, O., Pollak, M.R., Yao, G., and Zhou, J.. Guided tissue organization and disease modeling in a kidney tubule array. Biomaterials 183, 295, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ron, A., Azeloglu, E.U., Calizo, R.C., et al. Cell shape information is transduced through tension-independent mechanisms. Nat Commun 8, 2145, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Korolj, A., Laschinger, C., James, C., et al. Curvature facilitates podocyte culture in a biomimetic platform. Lab Chip 18, 3112, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Homan, K.A., Kolesky, D.B., Skylar-Scott, M.A., et al. Bioprinting of 3D convoluted renal proximal tubules on perfusable chips. Sci Rep 6, 1, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kotha, S.S., Hayes, B.J., Phong, K.T., et al. Engineering a multicellular vascular niche to model hematopoietic cell trafficking. Stem Cell Res Ther 9, 1, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rayner, S.G., Howard, C.C., Mandrycky, C.J., et al. Multiphoton-guided creation of complex organ-specific microvasculature. Adv Healthc Mater 10, 1, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Azizgolshani, H., Coppeta, J.R., Vedula, E.M., et al. High-throughput organ-on-chip platform with integrated programmable fluid flow and real-time sensing for complex tissue models in drug development workflows. Lab Chip 21, 1454, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Musah, S., Mammoto, A., Ferrante, T.C., et al. Mature induced-pluripotent-stem-cell-derived human podocytes reconstitute kidney glomerular-capillary-wall function on a chip. Nat Biomed Eng 1, 0069, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ishahak, M., Hill, J., Amin, Q., et al. Modular microphysiological system for modeling of biologic barrier function. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 8, 1, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Xie, R., Xie, R., Korolj, A., et al. H-FIBER: microfluidic topographical hollow fiber for studies of glomerular filtration barrier. ACS Cent Sci 6, 903, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wang, L., Tao, T., Su, W., Yu, H., Yu, Y., and Qin, J.. A disease model of diabetic nephropathy in a glomerulus-on-a-chip microdevice. Lab Chip 17, 1749, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Petrosyan, A., Cravedi, P., Villani, V., et al. A glomerulus-on-a-chip to recapitulate the human glomerular filtration barrier. Nat Commun 10, 3656, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Saleem, M.A., O'Hare, M.J., Reiser, J., et al. A conditionally immortalized human podocyte cell line demonstrating nephrin and podocin expression. J Am Soc Nephrol 13, 630, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chun, J., Zhang, J.Y., Wilkins, M.S., et al. Recruitment of APOL1 kidney disease risk variants to lipid droplets attenuates cell toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116, 3712, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Paquet, D., Kwart, D., Chen, A., et al. Efficient introduction of specific homozygous and heterozygous mutations using CRISPR/Cas9. Nature 533, 125, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Freedman, B.S., Brooks, C.R., Lam, A.Q., et al. Modelling kidney disease with CRISPR-mutant kidney organoids derived from human pluripotent epiblast spheroids. Nat Commun 6, 1, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sharmin, S., Taguchi, A., Kaku, Y., et al. Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived podocytes mature into vascularized glomeruli upon experimental transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol 27, 1778, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hobeika, L., Barati, M.T., Caster, D.J., McLeish, K.R., and Merchant, M.L.. Characterization of glomerular extracellular matrix by proteomic analysis of laser-captured microdissected glomeruli. Kidney Int 91, 501, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mollica, P.A., Booth-Creech, E.N., Reid, J.A., et al. 3D bioprinted mammary organoids and tumoroids in human mammary derived ECM hydrogels. Acta Biomater 95, 201, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Nagao, R.J., Xu, J., Luo, P., et al. Decellularized human kidney cortex hydrogels enhance kidney microvascular endothelial cell maturation and quiescence. Tissue Eng Part A 22, 1140, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Polacheck, W.J., Kutys, M.L., Tefft, J.B., and Chen, C.S.. Microfabricated blood vessels for modeling the vascular transport barrier. Nat Protoc 14, 1425, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Miller, J.S., Stevens, K.R., Yang, M.T., et al. Rapid casting of patterned vascular networks for perfusable engineered three-dimensional tissues. Nat Mater 11, 768, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lovett, M., Eng, G., Kluge, J.A., Cannizzaro, C., Vunjak-Novakovic, G., and Kaplan, D.L.. Tubular silk scaffolds for small diameter vascular grafts. Organogenesis 6, 217, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Eremina, V., Baelde, H.J., and Quaggin, S.E.. Role of the VEGF-A signaling pathway in the glomerulus: evidence for crosstalk between components of the glomerular filtration barrier. Nephron Physiol 106, 32, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Tuffin, J., Burke, M., Richardson, T., et al. A composite hydrogel scaffold permits self-organization and matrix deposition by cocultured human glomerular cells. Adv Healthc Mater 8, 1, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ricca, B.L., Venugopalan, G., and Fletcher, D.A.. To pull or be pulled: parsing the multiple modes of mechanotransduction. Curr Opin Cell Biol 25, 558, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Abdallah, M., Martin, M., El Tahchi, M.R., et al. Influence of hydrolyzed polyacrylamide hydrogel stiffness on podocyte morphology, phenotype, and mechanical properties. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 11, 32623, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Rockwood, D.N., Preda, R.C., Yücel, T., Wang, X., Lovett, M.L., and Kaplan, D.L.. Materials fabrication from Bombyx mori silk fibroin. Nat Protoc 6, 1612, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Nguyen, D.H.T., Stapleton, S.C., Yang, M.T., et al. Biomimetic model to reconstitute angiogenic sprouting morphogenesis in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 6712, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]