Abstract

HIV remains incurable due to the persistence of a latent viral reservoir found in HIV-infected cells, primarily resting memory CD4+ T cells. Depletion of this reservoir may be the only way to end this deadly epidemic. In latency, the integrated proviral DNA of HIV is transcriptionally silenced partly due to the activity of histone deacetylases (HDACs). One strategy proposed to overcome this challenge is the use of HDAC inhibitors (HDACis) as latency reversal agents to induce viral expression (shock) under the cover of antiretroviral therapy. It is hoped that this will lead to elimination of the reservoir by immunologic and viral cytopathic (kill). However, there are 18 isoforms of HDACs leading to varying selectivity for HDACis. In this study, we review HDACis with emphasis on their selectivity for HIV latency reversal.

Keywords: HIV, HDAC inhibitors, latency reversal, viral reservoir, shock and kill

Introduction

Since the occurrence of HIV/AIDS in 1981, scientists have worked tirelessly to find a cure for this deadly disease.1 It was not until 1996 that combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) was introduced, which has led to considerable reduction of morbidity and mortality in HIV-infected individuals.2 Even though this marks a great achievement in modern science, it can only control and not cure HIV infection. Combination ART helps reduce plasma HIV RNA to undetectable levels but the virus easily rebinds when treatment is interrupted.2 ART is thus limited by lifelong adherence, cumulative side effects, development of drug resistance, and unsustainable costs.3,4

The major barrier to finding a cure is the ability of HIV to establish an early reservoir of latently infected cells. This latent viral reservoir has been proposed to be made up of different types of cells such as macrophages, follicular dendritic cells, and CD4+ subsets of natural killer (NK) cells.5,6 However, the best-characterized latent reservoirs are the resting memory CD4+ T cells.6 Resting CD4+ T cells harbor proviruses that are silenced through a variety of mechanisms that inhibit replication, therefore making them imperceptible to the host immune response.7 Due to this barrier, scientists are looking for strategies to eliminate or incapacitate the latent reservoirs.

One such strategy is the shock and kill; elimination of latently infected cells with the use of latency reversing agents (LRAs).8 LRAs work by a variety of mechanisms to stimulate proviruses in latent reservoirs to allow for transcription, translation, and subsequent production of viruses. With ART, these newly expressed HIV will be incapable of reinfection and the latent reservoirs can then be eliminated by immunologic mechanisms or viral cytopathic effect.9

The ideal HIV LRA must be able to induce HIV provirus expression without global T cell activation.10 Several histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACis) satisfy this condition, making them one of the most studied LRAs.2,8 Studies have shown that deacetylation of histones by HDACs represses chromatin structure, which plays a vital role in the inhibition of HIV replication.11 By inhibiting HDACs, HDACis promote acetylation and unwrapping of chromatin to induce the expression of HIV.12

HDAC Mechanisms and HIV Latency

HDACs (properly called lysine deacetylases) are a class of enzymes that regulate transcription by removing acetyl groups from lysine residues on histones, specifically lysine 9 and 14 from histone 3 (H3K9 or H3K14) and lysine 16 from histone 4 (H4K16).13,14 This makes transcription factors less accessible to the tightly wrapped DNA.15 There are four classes (I–IV) based on their size, number of catalytic active sites, cellular localization, and homology to yeast HDAC protein.16,17 Class I, II, and IV, also referred to as the “classical family,” have zinc-dependent (Zn2+) active sites, whereas Class III are structurally different and are nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) dependent.18

Class I HDACs (the most studied in terms of HIV latency) consist of HDACs 1, 2, 3, and 8 and are localized in the nucleus. Class II is grouped into six HDACs, which are further subdivided into Class IIa (HDACs 4, 5, 7, and 9) and Class IIb (HDACs 6 and 10).19 Class II are mostly localized in the cytoplasm, but shuttle between the cytoplasm and nucleus depending on different signals received.19 HDAC 11 is the only member of Class IV and it is localized in the nucleus.19 Class III, also known as sirtuins, has seven members (SIRT 1–7) that have not yet been associated with HIV latency.16

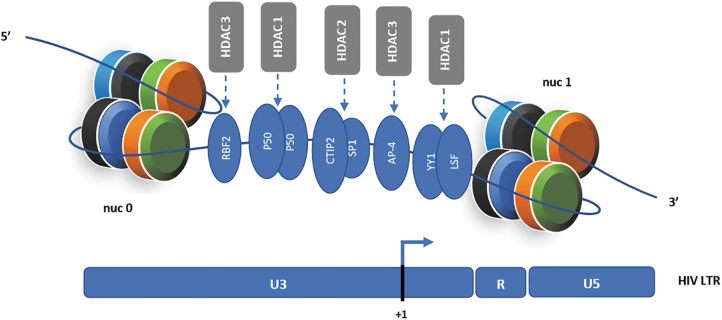

For latency to be achieved, HIV, like all other retroviruses, must integrate its proviral DNA into the host genome.20 Studies have shown that different transcription factors recruit HDACs to the HIV long terminal repeats (LTR) promoter after integration (Fig. 1), blocking efficient initiation and elongation of transcripts.13 Some of these transcription factors include COUP-TF interacting protein (CTIP2), Ying Yang 1 (YY1), late SV40 factor (LSF), Nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB p50), activating enhancer binding protein (AP-4), retinoblastoma-family protein 2 (RBF2), c-promoter-binding factor-1 (CBF-1), and specificity protein 1 (Sp1), which are known to primarily recruit HDACs 1 and 2.2,20

FIG. 1.

Chromatin organization of HIV LTR (promoter) and its association with HDACs and transcription factors in the setting of HIV latency. The HIV promoter is arranged in two nucleosomes (nuc 0 and nuc 1) consisting of two copies each of the core histones H2A (black), H2B (blue), H3 (orange), and H4 (green). The nucleotide +1 denotes transcriptional start site on the viral promoter. Transcription factors like RBF2, p50, CTIP2, Sp1, YY1, AP-4, and LSF recruit HDACs to the HIV LTR.20 These HDACs, in part, promote HIV latency by deacetylating the local histones directly at the provirus integrated site, which in turn brings about repression of chromatin and prevention of RNA polymerase II from binding. HDAC inhibitors block these HDACs and induce histone acetylation, which leads to reactivation of the HIV LTR. AP-4, activating enhancer binding protein; CTIP2, COUP-TF interacting protein; HDACs, histone deacetylases; LSF, late SV40 factor; LTR, long terminal repeats; RBF2, retinoblastoma-family protein 2; YY1, Ying Yang 1.

It is also known that HDAC 3 occupies a position at the HIV promoter and plays a significant role in suppressing transcription.21 Also, the HIV LTR has been found to be arranged in two nucleosomes, (nuc 0 and nuc 1), with the nuc 1 present downstream of the promoter, making remodeling of nuc 1 an important step for reactivation from latent HIV (Fig. 1).2,20 It has been documented that the use of HDACis alone are sufficient to remodel nuc 1.20,22

HDACis and HIV Reversal

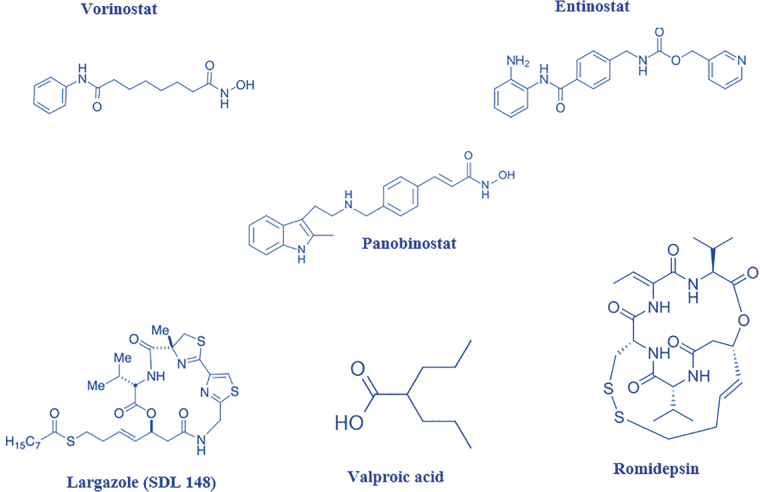

For functionality, HDACis have a cap group, which is used for targeting the surface of HDACs, a linker (aliphatic chain) and functional group that chelates zinc cations.20 Four examples of HDACi family structures are short-chain aliphatic acids (valproic and butyric acids), hydroxamic acids (trichostatin A, vorinostat, givinostat, largazole, and panobinostat), benzamides (entinostat and mocetinostat), and cyclic tetrapeptides and depsipeptides (trapoxin B and romidepsin) (Fig. 2).20 The hydroxamates are known to be the most potent with the short-chain aliphatic acids known to show feeble potency.23

FIG. 2.

Basic chemical structures of some representative HDAC inhibitors from different families.

Depending on their specificity, HDACis can be termed as selective or nonselective. The selective HDACis can further be divided into class selective or isoform selective based on whether they inhibit different isoforms within the same class or target a single HDAC isoform, respectively.17,23 HDACis of the hydroxamic acid group such as vorinostat, givinostat, and panobinostat are known to inhibit many of the HDAC class isoforms and have been termed pan-selective or nonselective HDACis because they are nonselective.18 However, there is evidence that HDACis such as entinostat, mocetinostat, and romidepsin are more selective as they are known to specifically target class I HDACs.18,20 Another set of class I isoform-selective HDACis are the largazoles SDL256, SDL256, and JMF1080.16 Tubastatin A and tubacin are typical examples of isoform-selective inhibitors as they act only on HDAC 6.23

Class I selective HDACis are usually distinguished from the pan-HDACis by their inability to acetylate tubulin (tubulin is only deacetylated by HDAC 6). Hence, to assess the selectivity of HDACis, a Western blot can be used to probe if the inhibitor only promotes acetylation of histone 3 or histone 4 (class I selective) or both histone 3 or 4 and tubulin (Pan HDACi).16,24,25 It must be noted that HDACi selectivity depends on the concentration of the compound used. Many isoform-selective HDACis become less selective when used at higher concentrations.16,25,26 Examples of HDACis that have been studied for their effect on HIV infection are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of Some Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors Used to Induce HIV from Latency

| HDAC inhibitor | HDAC selectivity | Assay | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Valproic acids | I, IIa | In vitro | 21,27–32 |

| Butyric acids | I | In vitro | 2,20 |

| Trichostatin A | I, IIa, IIb | In vitro | 20,27,29,31 |

| Vorinostat | I, IIa, IIb | In vitro, in vivo | 21,27–29,31,33–35 |

| Givinostat | I, IIa, IIb | In vitro, in vivo | 36,37 |

| Panobinostat | I, IIa, IIb | In vitro, in vivo | 2,38 |

| Entinostat | HDAC 1, 2, 3 | In vitro, in vivo | 2,31,33 |

| Mocetinostat | I | In vitro | 39 |

| Trapoxin B | HDAC 1, HDAC 6 | In vitro | 20 |

| Romidepsin | HDAC 1, 2 | In vitro, in vivo | 40 |

| SDL 148 | I | In vitro | 16 |

| JMF 1080 | I | In vitro | 16 |

| SDL 256 | I | In vitro | 16 |

HDAC, histone deacetylase.

HDACis in HIV Clinical Trials

Most HDACis have been analyzed in vitro for their ability to reactivate HIV from latency, but very few have been tested in vivo. However, the use of HDACis in vivo is not novel, as HDACs are implicated in other diseases such as cancer. Intensive research has already been done on the pharmacological and toxicological properties of multiple HDACis as anticancer drugs.41–43 Thus, HDACis are one of the advanced latency reversal agents in terms of clinical studies, examples of which are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors in Completed and Ongoing HIV Clinical Trials

| HDAC inhibitor | Regimen | Phase | No. of participants | Outcome | Study identifier | Year completed | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vorinostat | 400 mg; single dose and 10 doses given at 72-h intervals | I/II | 16 | Increase in cell-associated HIV-RNA within circulating resting CD4+ T cells, but no measurable decrease in frequency of latent infection within resting CD4+ T cells | NCT01319383 | 2016 | 44 |

| Romidepsin | 0.5, 2, 5 mg/m2 (single dose) or 5 mg (multidose on days 0, 14, 28, and 48) | I/II | 59 | No significant increase in plasma viremia or cell-associated unspliced HIV-1 RNA | NCT01933594 | 2018 | 45 |

| Panobinostat | 20 mg; 3 times a week for 8 weeks | I/II | 15 | Cell-associated unspliced HIV-1 RNA increased significantly at time points where panobinostat were taken | NCT01680094 | 2014 | 46 |

| Panobinostat+IFN-alpha 2a | 15 mg; on days 0, 2, and 4 of treatment week | I/II | 34 | Ongoing | NCT02471430 | — | 47 |

| Chidamide | 10 mg; eight oral doses on days 0, 3, 7, 10, 14, 17, 21, and 24 | I/II | 7 | Robust and repeated plasma viral rebound with increased cell associated HIV-1 RNA during treatment and reduction in cell-associated HIV-1 DNA | NCT02513901 | 2016 | 48 |

Are Isoform-Selective Compounds Better Reversal Agents?

Owing to their nonselectivity, pan-HDACis have been shown to come with a degree of toxicity as they interfere with many cellular processes.16,24,25 In cancer treatment, such side effects include dehydration, thrombocytopenia, diarrhea, fatigue, anorexia, and nausea, among others.49,50 Due to this shortcoming, the use of more selective HDACis, especially for class I HDACs, has been proposed to reduce off-target effects.24,25,33,51 However, the question is whether class or isoform-selective compounds will have the same potency as the pan-HDACis. We and others have demonstrated that class I selective inhibitors could be more potent than vorinostat in reactivating HIV in cell lines and primary cell latency models.16,24,25 However, of the class I selective compounds, only romidepsin has entered clinical studies.52

Although the search for more selective HDACis is of importance to prevent untoward side effects, there is evidence that being too selective may not bring about significant viral reactivation. Barton et al. showed that inhibitors that were isoform selective for either HDAC 1 or 2 alone did not activate latent HIV.13 Their data suggested that HDAC 3 was vital for reactivation of quiescent HIV proviruses.13 It was also shown that concurrent knockdown of HDAC 1 or 2 with HDAC 3 did not increase expression from the HIV-1 LTR any further than the depletion of HDAC 3 alone. However, it was the combined knockdown of HDACs 1, 2, and 3 that showed the most expression.13,52 This shows that in terms of selectivity, a class I selective HDACi will be more appropriate than an isoform-selective HDACi for HIV reactivation studies.

So far, studies show that HDACis are not enough to reduce the viral reservoir size when tested in vivo.16,24,25 Single-cell RNA sequencing and dual-label reporter virus assays show that a minority of latently infected CD+ T cells respond to LRAs, including HDACis, likely due to heterogeneity in chromatin organization at different integration sites.53–56 These data should be taken in the backdrop of the fact that only a handful of HDACis have been tested in vivo. Indeed, all the ones tested were not specifically developed for HIV, but for cancer and other indications.

With in vitro and ex vivo data showing that class I selective HDACis could be more potent LRAs, several groups have been encouraged to develop new HDACis for HIV latency reversal.57,58 It will be important to advance these compounds through the pipeline to clinical trials. One such compound developed by Merck can produce significant amounts of p24 in resting CD4+ T cells isolated from aviremic patients.59 Another HDACi, Chidamide, shows strong promise and is currently in clinical trials.48

However, given the characteristics of the integrated provirus, successful reactivation of a majority of the latent HIV is likely to come from combinations of different LRAs, including selective HDACis. As such, combination therapy of HDACis and protein kinase C (PKC) agonist such as bryostatin-1 has been proposed. This combination helps lower the concentration of individual agents to clinically acceptable levels, while maintaining robust latency reversal. These studies highlighted the importance of Class I selective HDACis and not pan-HDACis for combination therapy.16,24,25 In one of these studies, it was shown that, entinostat (Class I HDACi) in combination with bryostatin-1 induced maximal viral outgrowth compared to its pan-HDACi counterparts.24 However, when the pan-HDACis were introduced in that combination, the viral outgrowth seen resembled that of pan-HDACis alone, suggesting that pan-HDACis have the tendency to inhibit robust HIV gene expression.

Probing this inhibitory effect revealed that Pan HDACis like vorinostat inhibit NF-κB and Hsp90, two important HIV-1 transcription factors.24,25 NF-κB is required for bryostatin-1-induced cell activation, while the activity of Hsp90 is promoted by HDAC 6. Hence, pan-HDACis capable of inhibiting HDAC 6 will acetylate Hsp90 and inhibit its function.24 This makes it imperative to try combinations of class I selective HDACis and PKC analogs. Although PKC agonists are the most potent LRAs ex vivo and in mouse studies, the only human trial done so far failed to increase viral RNA in the serum.60,61 The doses of bryostatin-1 used in this trial were very conservative for fear of side effects from proinflammatory cytokine release and could account for those results.

In this regard, selective HDACis could come to the rescue as modulators of inflammation caused by the PKC agonists like brostatin-1 and ingenols. Recently, Spivak and colleagues showed that a class I HDACi, suberohydroxamic acid (SBHA), did not reactivate HIV in CD4+ T cells isolated from aviremic patients, but could prevent the release of proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-5, IL-2r, and IL-17.62 In addition, entinostat reduced production of proinflammatory cytokines in animal model studies.63,64

Therefore, it is imperative to try different combinations of PKC analogs and selective HDACis to determine a combination that could synergize in HIV latency reversal and simultaneously reduce cytokine release. For instance, one study showed that prostratin could enhance NK cell killing of CD4+ T cells with reactivated HIV. Studies have now demonstrated that PKC analogs, HDACis and bromodomain inhibitors, each tend to reactivate HIV proviruses from distinct unique loci of the chromatin.54 While these findings affirm the belief that a singly LRA is unlikely to result in significant latency reversal, it provides hope that a carefully designed cocktail of LRAs could make the shock and kill approach successful.

Perspectives and Conclusion

In light of the shock and kill approach, HDACis have so far not produced encouraging results in vivo. This is because, several mechanisms contribute to the establishment and maintenance of latency. Also, the heterogeneous nature of the viral reservoir as well as the integration site of the provirus have contributed to this limited success seen in HDACis.5,52 This calls for a better understanding of the silencing mechanisms underlining HIV latency.

While it is important for LRAs such as HDACis to be potent enough to reactivate HIV, it will be even better if they could eliminate the reservoir. This can only be achieved when adequate amounts of viral proteins are expressed within the infected cells. Even after significant amounts of viral proteins are made in latently infected CD4+ T cells, several obstacles to their killing remain. First, the HIV regulatory proteins (nef) downregulate expression of MHC class I and limits the presentation of peptides to CD8+ T cells. Hence, the most potent HDACi might interfere with reservoir clearance through cytotoxic T cell-mediated killing. Second, latently infected cells have high levels of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2. Third, some HDACis may inhibit the function of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells.

Finally, chronic T cell exhaustion and immune escape mutations in chronically infected patients also present formidable obstacles.65 To overcome these inherent challenges to killing, studies that seek to combine HDACis with therapeutic vaccines, interferon, toll-like receptor agonists, broadly neutralizing antibodies, and proapoptotic compounds have to be intensified.66

Due to the heterogeneity of the viral reservoir, it will be of interest to investigate latency reversal agents that can affect the different reservoir types, despite their physiological differences. Also, most of these HIV reservoirs are known to be found in sanctuary sites. Hence, effective latency reversal agents have to be able to penetrate these sites and optimal drug delivery approaches should be considered for this.

Finally, it has been shown that isoform-selective HDACis are better reversal agents than their nonselective counterparts. However, it is becoming clear that the use of a single agent, such as HDACis alone, may not be enough to truly shock and clear the reservoir. Therefore, further experimental and clinical studies are required to assess the effectiveness of new compounds, with different mechanisms of action, and combinations of compounds to reverse HIV latency and eliminate the reservoir.

Authors' Contributions

A.T.B., E.Y.B., and G.B.K. conceived and designed the concepts of the review, and A.A.-M. assisted with the literature search and article writing. All authors were involved in writing and reviewing the article.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This article is part of the EDCTP2 program supported by the European Union (Grant No. TMA2017SF-1955, H-CRIS) to G.B.K. The funder had no role in this publication.

References

- 1. Barré-sinoussi F, Ross AL, Delfraissy J. Past, present and future: 30 years of HIV research. Nat Publ Gr 2013;11:877–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wightman F, Ellenberg P, Churchill M, Lewin SR. HDAC inhibitors in HIV. Immunol Cell Biol 2012;90:47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Trono D, Van LC, Rouzioux C, et al. HIV Persistence and the prospect of long-term drug-free remissions for HIV-infected individuals. Science 2010;329:174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Richman DD, Margolis DM, Delaney M, Greene WC, Hazuda D, Pomerantz RJ. The challenge of finding a cure for HIV infection. Science 2009;323:1304–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ait-Ammar A, Kula A, Darcis G, et al. Current status of latency reversing agents facing the heterogeneity of HIV-1 cellular and tissue reservoirs. Front Microbiol 2020;10:3060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Blankson JN, Persaud D, Siliciano RF. The challenge of viral reservoirs in HIV-1 infection. Annu Rev Med 2002;53:557–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bruner KM, Hosmane NN, Siliciano RF. Towards an HIV-1 cure: Measuring the latent reservoir. Trends Microbiol 2015;23:192–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rasmussen TA, Lewin SR. Shocking HIV out of hiding. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2016;11:394–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Laird GM, Bullen CK, Rosenbloom DIS, et al. Ex vivo analysis identifies effective HIV-1 latency—Reversing drug combinations. J Clin Invest 2015;125:1901–1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Matalon S, Rasmussen T. Histone deacetylase inhibitors for purging hIV-1 from the latent reservoir. Mol Med 2011;17:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Margolis DM. Histone deacetylase inhibitors and HIV latency. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2011;6:25–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Blazkova J, Chun T-W, Belay BW, et al. Effect of histone deacetylase inhibitors on HIV production in latently infected, resting CD4+ T cells from infected individuals receiving effective antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis 2012;206:765–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Barton KM, Archin NM, Keedy KS, et al. Selective HDAC inhibition for the disruption of latent HIV-1 infection. PLoS One 2014;9:e102684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shang HT, Ding JW, Yu SY, Wu T, Zhang QL, Liang FJ. Progress and challenges in the use of latent HIV-1 reactivating agents. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2015;36:908–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Archin NM, Keedy KS, Espeseth A, Dang H, Hazuda DJ, Margolis DM. Expression of latent human immunodeficiency type 1 is induced by novel and selective histone deacetylase inhibitors. AIDS 2013;23:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Albert BJ, Niu A, Ramani R, et al. Combinations of isoform-targeted histone deacetylase inhibitors and bryostatin analogues display remarkable potency to activate latent HIV without global T-cell activation. Sci Rep 2017;7:7456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bieliauskas AV, Pflum MKH. Isoform-selective histone deacetylase inhibitors. Chem Soc Rev 2008;37:1402–1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Balasubramanian S, Verner E, Buggy JJ. Isoform-specific histone deacetylase inhibitors: The next step? Cancer Lett 2009;280:211–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Uba AI, Yelekçi K. Identification of potential isoform-selective histone deacetylase inhibitors for cancer therapy: A combined approach of structure-based virtual screening, ADMET prediction and molecular dynamics simulation assay. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2017;1102:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shirakawa K, Chavez L, Hakre S, Calvanese V, Verdin E. Reactivation of latent HIV by histone deacetylase inhibitors. Trends Microbiol 2013;21:277–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Archin NM, Espeseth A, Parker D, Cheema M, Hazuda D, Margolis DM. Expression of latent HIV induced by the potent HDAC inhibitor suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2009;25:207–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lint C Van, Emiliani S, Ott M, Verdin1 E. Transcriptional activation and chromatin remodeling of the HIV-1 promoter in response to histone acetylation-iB/tat/TNF-a/trapoxin/trichostatin A. EMBO J 1996;15:1112–1120. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ganai SA. Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors—Epidrugs for Neurological Disorders. Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd., Jammu and Kashmir, India [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zaikos TD, Painter MM, Sebastian Kettinger NT, Terry VH, Collins KL. Class 1-selective histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors enhance HIV latency reversal while preserving the activity of HDAC isoforms necessary for maximal HIV gene expression. J Virol 2018;92:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Heffern EFW, Ramani R, Marshall G, Kyei GB. Identification of isoform-selective hydroxamic acid derivatives that potently reactivate HIV from latency. J Virus Erad 2019;5:84–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ho TCS, Chan AHY, Ganesan A. Thirty years of HDAC inhibitors: 2020 insight and hindsight. J Med Chem 2020;63:12460–12484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Burnett JC, Lim K, Calafi A, Rossi JJ, Schaffer DV, Arkin AP. Combinatorial latency reactivation for HIV-1 subtypes and variants. J Virol 2010;84:5958–5974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Contreras X, Schweneker M, Chen CS, et al. Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid reactivates HIV from latently infected cells. J Biol Chem 2009;284:6782–6789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Huber K, Doyon G, Plaks J, Fyne E, Mellors JW, Sluis-Cremer N. Inhibitors of histone deacetylases: Correlation between isoform specificity and reactivation of HIV type 1 (HIV-1) from latently infected cells. J Biol Chem 2011;286:22211–22218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shehu-Xhilaga M, Rhodes D, Wightman F, et al. The novel histone deacetylase inhibitors metacept-1 and metacept-3 potently increase HIV-1 transcription in latently infected cells. AIDS 2009;23:2047–2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Reuse S, Calao M, Kabeya K, et al. Synergistic activation of HIV-1 expression by deacetylase inhibitors and prostratin: Implications for treatment of latent infection. PLoS One 2009;4:1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ylisastigui L, Archin NM, Lehrman G, Bosch RJ, Margolis DM. Coaxing HIV-1 from resting CD4 T cells: Histone deacetylase inhibition allows latent viral expression. AIDS 2004;18:1101–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Savarino A, Mai A, Norelli S, et al. “Shock and kill” effects of class I-selective histone deacetylase inhibitors in combination with the glutathione synthesis inhibitor buthionine sulfoximine in cell line models for HIV-1 quiescence. Retrovirology 2009;6:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Archin NM, Liberty AL, Kashuba AD, et al. Administration of vorinostat disrupts HIV-1 latency in patients on antiretroviral therapy. Nature 2012;487:482–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Choi BS, Lee HS, Oh YT, et al. Novel histone deacetylase inhibitors CG05 and CG06 effectively reactivate latently infected HIV-1. AIDS 2010;24:609–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Matalon S, Palmer BE, Nold MF, et al. The histone deacetylase inhibitor ITF2357 decreases surface CXCR4 and CCR5 expression on CD4+ T-cells and monocytes and is superior to valproic acid for latent HIV-1 expression in vitro. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010;54:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tan J, Cang S, Ma Y, Petrillo RL, Liu D. Novel histone deacetylase inhibitors in clinical trials as anti-cancer agents. J Hematol Oncol 2010;3:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Atadja P. Development of the pan-DAC inhibitor panobinostat (LBH589): Successes and challenges. Cancer Lett 2009;280:233–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Boumber Y, Younes A, Garcia-Manero G. Mocetinostat (MGCD0103): A review of an isotype-specific histone deacetylase inhibitor. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2011;20:823–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Furumai R, Matsuyama A, Kobashi N, et al. FK228 (depsipeptide) as a natural prodrug that inhibits class I histone deacetylases. Cancer Res 2002;62:4916–4921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Eckschlager T, Plch J, Stiborova M, Hrabeta J. Histone deacetylase inhibitors as anticancer drugs. Int J Mol Sci 2017;18:1–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Whittle JR, Desai J. Histone deacetylase inhibitors in cancer: What have we learned? Cancer 2015;121:1164–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shah RR. Safety and tolerability of histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors in oncology. Drug Saf 2019;42:235–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Archin NM, Kirchherr JL, Sung JAM, et al. Interval dosing with the HDAC inhibitor vorinostat effectively reverses HIV latency. J Clin Invest 2017;127:3126–3135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. McMahon DK, Zheng L, Cyktor JC, et al. A phase 1/2 randomized, placebo-controlled trial of romidespin in persons with HIV-1 on suppressive antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis 2021;224:648–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rasmussen TA, Tolstrup M, Brinkmann CR, et al. Panobinostat, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, for latent virus reactivation in HIV-infected patients on suppressive antiretroviral therapy: A phase 1/2, single group, clinical trial. Lancet HIV 2014;1:e13–e21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Reducing the Residual Reservoir of HIV-1 Infected Cells in Patients Receiving Antiretroviral Therapy—Full Text View—ClinicalTrials.gov. [cited 2021 Mar 8]. Available at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02471430, accessed March 8, 2021.

- 48. Li JH, Ma J, Kang W, et al. The histone deacetylase inhibitor chidamide induces intermittent viraemia in HIV-infected patients on suppressive antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med 2020;21:747–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gryder BE, Sodji QH, Oyelere AK. Targeted cancer therapy: Giving histone deacetylase inhibitors all they need to succeed. Future Med Chem 2012;4:505–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Subramanian S, Bates SE, Wright JJ, Espinoza-Delgado I, Piekarz RL. Clinical toxicities of histone deacetylase inhibitors. Pharmaceuticals 2010;3:2751–2767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Keedy KS, Archin NM, Gates AT, Espeseth A, Hazuda DJ, Margolis DM. A limited group of class I histone deacetylases acts to repress human immunodeficiency virus type 1 expression. J Virol 2009;83:4749–4756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Manson McManamy ME, Hakre S, Verdin EM, Margolis DM. Therapy for latent HIV-1 infection: The role of histone deacetylase inhibitors. Antivir Chem Chemother 2014;23:145–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Rato S, Rausell A, Muñoz M, Telenti A, Ciuffi A. Single-cell analysis identifies cellular markers of the HIV permissive cell. PLoS Pathog 2017;13:1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Abner E, Stoszko M, Zeng L, et al. A new quinoline BRD4 inhibitor targets a distinct latent HIV-1 reservoir for reactivation from other “Shock” Drugs. J Virol 2018;92. Available at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29343578, accessed January 26, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Chen HC, Martinez JP, Zorita E, Meyerhans A, Filion GJ. Position effects influence HIV latency reversal. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2017;24:47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Chen HC, Zorita E, Filion GJ. Using barcoded HIV ensembles (B-HIVE) for single provirus transcriptomics. Curr Protoc Mol Biol 2018;122. Available at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29851299, accessed January 26, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Clausen DJ, Liu J, Yu W, et al. Development of a selective HDAC inhibitor aimed at reactivating the HIV latent reservoir. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2020;30. Available at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32738976, accessed January 26, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Stoszko M, Ne E, Abner E, Mahmoudi T. A broad drug arsenal to attack a strenuous latent HIV reservoir. Curr Opin Virol 2019;38:37–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Liu J, Kelly J, Yu W, et al. Selective class I HDAC inhibitors based on aryl ketone zinc binding induce HIV-1 protein for clearance. ACS Med Chem Lett 2020;11:1476–1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Marsden MD, Loy BA, Wu X, et al. In vivo activation of latent HIV with a synthetic bryostatin analog effects both latent cell “kick” and “kill” in strategy for virus eradication. PLoS Pathog 2017;13. Available at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28934369, accessed January 26, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Gutiérrez C, Serrano-Villar S, Madrid-Elena N, et al. Bryostatin-1 for latent virus reactivation in HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 2016;30:1385–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Larragoite ET, Nell RA, Martins LJ, Barrows LR, Planelles V, Spivak AM. Histone deacetylase inhibition reduces deleterious cytokine release induced by ingenol stimulation. Biochem Pharmacol 2022;195:114844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lin HS, Hu CY, Chan HY, et al. Anti-rheumatic activities of histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors in vivo in collagen-induced arthritis in rodents. Br J Pharmacol 2007;150:862–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zhang ZY, Zhang Z, Schluesener HJ. MS-275, an histone deacetylase inhibitor, reduces the inflammatory reaction in rat experimental autoimmune neuritis. Neuroscience 2010;169:370–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kim Y, Anderson JL, Lewin SR. Getting the “Kill” into “Shock and Kill”: Strategies to eliminate latent HIV. Cell Host Microbe] 2018;23:14–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Zerbato JM, Purves HV, Lewin SR, Rasmussen TA. Between a shock and a hard place: Challenges and developments in HIV latency reversal. Curr Opin Virol 2019;38:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]