Abstract

Accurate detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is of great importance to control the COVID-19 pandemic. The gold standard assays for COVID-19 diagnostics are mainly based on separately detecting open reading frame 1ab (ORF1ab) and nucleoprotein (N) genes by RT-PCR. However, the current approaches often obtain false positive-misdiagnose caused by cross-contamination or undesired amplification. To address this issue, herein, we proposed a dumbbell-type triplex molecular switch (DTMS)-based, logic-gated strategy for high-fidelity SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection. The DTMS consists of a triple-helical stem region and two-loop regions for recognizing the ORF1ab and N genes of SARS-CoV-2. Only when the ORF1ab and N gene are concurrent, DTMS experiences a structural rearrangement, thus, bringing the two pyrenes into spacer proximity and leading to a new signal readout. This strategy allows detecting SARS-CoV-2 RNA with a detection limit of 1.3 nM, independent of nucleic acid amplification, holding great potential as an indicator probe for screening of COVID-19 and other population-wide epidemics.

Keywords: Dumbbell-type triplex molecular switch, Logic-gate, SARS-CoV-2 RNA, High-fidelity

1. Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)-caused a serious outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), because of its highly contagious properties, has posed a severe threat in public health and medical healthcare [1], [2], [3], [4]. In particular, some infected individuals without any significant symptoms may transmit the SARS-CoV-2 to those non-infected individuals inadvertently, thus leading to a high transmission rate [5], [6], [7]. Therefore, it is an urgent demand to develop an effective method to identify those infected individuals as accurately as possible to curb the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 [8], [9], [10].

Typically, nucleic acid amplification tests based on quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) have been regarded as the current gold standard for early diagnostics of viral nucleic acids [11], [12], [13], [14]. In this protocol, TaqMan probes, short DNA sequences labeled fluorophore and quencher at each end, were served as fluorescent reporters [15]. During PCR extension, the TaqMan probe is cleaved nucleotide by nucleotide due to the exonuclease activity of the Taq polymerase [16], [17]. Thus, the fluorophore moves away from the quencher, resulting in an increased signal. Although it has been used to identify SARS-CoV-2 infection [18], [19], [20], [21], some notable disadvantages still remain. The TaqMan probes often contain 25- to 35-nucleotides to ensure their binding specificity [22]. The separation between fluorophore and quencher generates a certain background signal due to an imperfect quenching effect. To distinguish the background signal during detection, multiple rounds of amplification are required, which not only prolongate the total run time but also increase the probability of aerosol cross-contamination and undesired amplification of the sample [23]. Furthermore, the widely used method of SARS-CoV-2 detection in clinical diagnostics is two target sequences assay. Given that the ORF1ab and N genes were identified in the same tube in a parallel manner by allotting their own primers and fluorescence probes, cross-reaction may occur between primer and probe, probe and probe, thereby generating a false-positive signal [24]. Thus, there is an ongoing need to develop a new fluorescent report probe to guarantee detection accuracy.

Herein, we report a dumbbell-type triplex molecular switch (DTMS)-based logic-gated strategy for rapid, accurate, and sensitive SARS-CoV-2 RNA analysis. The specially designed DTMS contains a stem region to form a triple helix by T-A·T and C-G·C+ via conventional Watson-Crick and non-conventional Hoogsteen interactions, and two loop regions to recognize the open reading frame 1ab (ORF1ab) and nucleoprotein (N) genes of SARS-CoV-2 RNA genome, respectively, followed by labeling pyrene fluorophore at two terminals. In the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA, the loop regions of DTMS can recognize and hybridize with the ORF1ab and N genes of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA genome. Then, the DTMS experiences a structural rearrangement and two pyrene fluorophores get close proximity, leading to a new signal readout. Compared with Taqman probe, this probe can greatly reduce the fluorescent background signal based on fluorescence property of pyrene excimer and reduce the false-positive rate by taking advantage of AND-logic gate. The DTMS holds great potential as an indicator probe for screening COVID-19 and other population-wide epidemics.

2. Experimental section

2.1. Materials and chemicals

All of the DNA/RNA strands used in this study were synthesized and purified by Sangon Biotechnology Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China), and their sequences are listed in supplementary material (Table S1). Spermine (≥ 96%) was purchased from Beijing Dingguo Changsheng Biotech Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). TEMED was purchased from Aladdin Bio-Chem Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). DNase I was acquired from Biyuntian Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Other biochemical reagents were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Other chemical reagents and solvents were analytical grades without further purification. Ultrapure water (18.2 MΩ·cm−1, Milli-Q) was used throughout all experiments.

2.2. Instruments

Fluorescence spectra were recorded using Photon Technology International (PTI) spectrofluorometer (USA). All the spectrum measurements were performed at 37 °C unless otherwise specified. The excitation wavelength of PTI was 345 nm, the scanning wavelength was 360–600 nm, the slit width was 5 nm, the response time interval was set to 0.5 s, the temperature was set to 25 °C, and the optical path was set to 1.0 cm. The circular dichroism (CD) spectra were performed on a MOS-500 spectropolarimeter. The native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) was imaged on a ChemiDoc XRS+ gel imager (BIO-RAD).

2.3. Fabrication of DTMS

All DNA strands were dissolved in phosphate buffer saline (10 mM PBS, 0.5 μM Spermine, 5 mM MgCl2, pH 6.5), respectively, and annealed at 95 °C for 5 min by using PCR thermal cycler, followed by a natural cooling procedure to room temperature. The DTMS was fabricated by treating its precursor with the above buffer noting that the DTMS should be fresh when used. The fabrication of DTMS was characterized by fluorescence and circular dichroism (CD) spectra methods, in which the fluorescence spectra scanned from 400 nm to 700 nm with an excitation wavelength of 375 nm, while the CD spectra were collected from 200 nm to 350 nm.

2.4. Logic-gated detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA

For the logic-gated detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA, two gene fragments (ORF1ab and N gene) were simultaneously presented in the solution of pyrene-labeled DTMS with indicated concentration and incubated at ambient temperature for 20 min. Subsequently, γ-cyclodextrin (γ-CD) was introduced into the above solution for a small period of time and was transferred into a quartz dish for fluorescence measurement. The sample containing a single target gene fragment (ORF1ab or N gene) was set as the control group, while the ultrapure water was set as the blank group. The fluorescence measurement was adopted under indicated parameters: the excitation wavelength of 345 nm, the scanning range from 360 nm to 600 nm, the slit width of 5 nm, and the response time interval of 0.5 s, respectively. Each experiment was performed three parallel times.

2.5. PAGE analysis

PAGE was used to characterize the formation of DTMS and the combination of DTMS and target. The PAGE was carried out in 1 ×Tris-Mg2+ buffer (pH 6.5). The electrophoresis was performed at 120 V for 2.5 h after loading 10 μL samples (1 μM) into each lane, the gels were scanned via the Bio-RAD gel imaging system.

2.6. Optimization of the experiment conditions

For the optimization of the experimental conditions of DTMS synthesis, different reaction times, magnesium ion concentration, spermine concentration, γ-CD concentration, and pH value were designed, DTMS reacts with the targets at the same concentration under different conditions. The fluorescence spectra were recorded under the parameters setting the excitation band of PTI at 345 nm, scanning wavelength range 360 nm∼ 540 nm, and record fluorescence values at 490 nm.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Principle of the logic-gated detection strategy based on DTMS

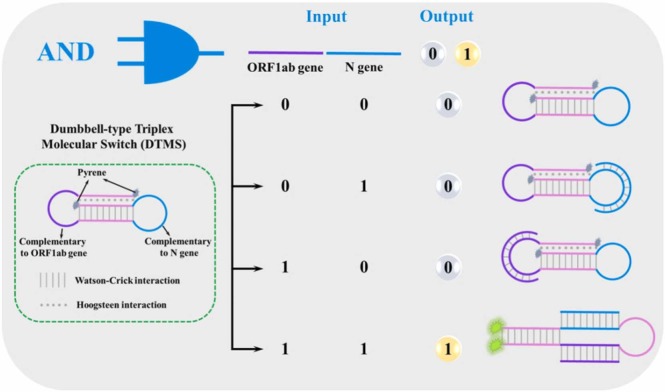

To achieve accurate and high-fidelity discrimination toward SARS-CoV-2 RNA, we designed a novel logic gate-coupled DTMS-based detection strategy. The DTMS consisting of a stem region and two-loop regions is shown in Scheme 1, in which the stem region is a triple-helical structure formed by three short DNA fragments within a long strand via conventional Watson-Crick and non-conventional Hoogsteen interactions, while two loop regions can recognize the ORF1ab and N gene of SARS-CoV-2 RNA genome, respectively. In addition, the terminals of the DTMS were labeled with two pyrene fluorophores (Scheme 1), making use of the unique property of pyrene to form an excited-state excimer with a relatively high quantum yield and long lifetime [25], [26], [27]. Initially, two pyrene fluorophores are far from each other after the formation of DTMS, leading to a fluorescence signal corresponding to a pyrene monomer at 370 nm and 390 nm. When both the ORF1ab and N genes of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA genome are present, the structure of DTMS was thoroughly rearranged and two pyrene fluorophores suffer from close proximity with the assistance of γ-CD, thus resulting in a considerable pyrene excimer emission at 490 nm. However, the absence of the ORF1ab or N gene of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA genome cannot induce the thorough rearrangement of the structure of DTMS. As a consequence, the two pyrene fluorophores still remain distant, thereby without the generation of pyrene excimer emission. Therefore, SARS-CoV-2 RNA can be discriminated in an accurate and high-fidelity manner.

Scheme 1.

Illustration of DTMS-based AND-logic-gated identification of the ORF1ab and N genes of SARS-CoV-2 RNA genome.

3.2. The characterization of fabricated DTMS

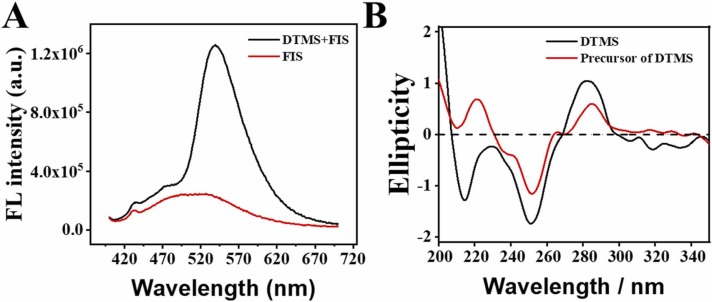

The successful fabrication of DTMS is a prerequisite for logic-gated SARS-CoV-2 RNA discrimination, and thus should be carefully investigated. Firstly, fisetin (FIS), as a frequently-used triple-helical structure-recognition dye, was utilized [28]. As shown in Fig. 1A, when the FIS was specifically embedded in DTMS via stacking interaction, its fluorescence emission at 540 nm dramatically enhanced (red), while FIS shows weak fluorescence in the presence of DTMS (black). Additionally, circular dichroism (CD) spectra were used to explore the secondary structure before and after the formation of DTMS [29]. As seen in Fig. 1B, for the precursor of DTMS, a positive peak at 280 nm and a negative peak at 250 nm were observed (red). However, when the DTMS forms, a new peak at 210 occurred, along with relatively strong peaks at 280 and 250 nm, respectively (black). The above results demonstrated the successful fabrication of DTMS.

Fig. 1.

(A) Fluorescence intensity of FIS (400 nM) without (red) and with (black) the addition of DTMS (100 nM) in the phosphate buffer saline. (B) CD spectrograph of DTMS (2 μM) (black) and the precursor of DTMS (2 μM) (red) in the phosphate buffer saline.

3.3. The nuclease resistance of the fabricated DTMS

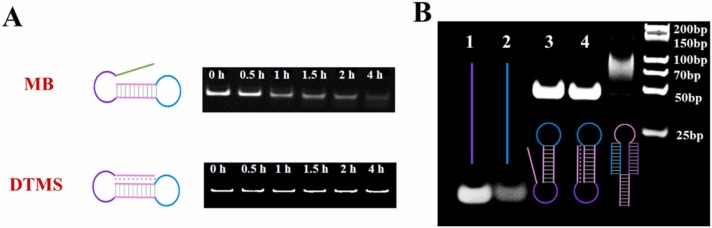

The previous study demonstrated that the triple helix possesses certain resistance to DNase I cleavage. To this end, we treated fabricated DTMS with a certain amount of DNase I, and adopted PAGE to examine its nuclease resistance, while a random hairpin-structured molecule beacon was set as the control. As seen in Fig. 2A, the hairpin-structured molecule beacon (MB) was degraded gradually by DNase I with the extended time, while DTMS showed negligible change even treated with DNase I for 4 h.

Fig. 2.

PAGE analysis. (A) Characterization of the nuclease resistance to DNase I cleavage of MB and DTMS. (B) Verification of the hybridization of DTMS with the ORF1ab and N gene. Lane 1: ORF1ab gene; lane 2: N gene; lane 3: the precursor of DTMS; lane 4: DTMS; lane 5: DTMS + ORF1ab gene + N gene; lane 6: DNA marker.

To further study the specific cleavage of DNase I on the nucleic acid molecular switch, according to the Miltonian equation: 1 / V0 = Km / Vmax× 1 / [S] + 1 / Vmax, and calculate the Miltonian constant——Km, the smaller the Km is, the higher the affinity between enzyme and substrate is, and the corresponding substrate is easier to be cut by enzyme [30]. First, the fluorescence intensity of different concentrations of MB and DTMS treated with DNase I within 1800 s was detected, as shown in Fig. S1 and Fig. S2, followed by taking the approximate speed at 600 s as V0 and substituting it into the Miltonian equation. As shown in Fig. S3 and Fig. S4, with 1 / V0 as the vertical axis and 1 / [S] as the horizontal axis, make a double reciprocal graph. The fitting equation and Km value were obtained through origin linear fitting as follows: MB: 1 / V = 0.0007992 + 0.0125 / [S], R2 = 0.97, Km (MB) = 15.64 nM; DTMS: 1 / V = 0.00173 + 0.07716 / [S], R2 = 0.99, Km (DTMS) = 44.60 nM. It’s suggested that DNase I has a strong cutting ability for MB, but for the CTMB and DTMS cutting capability is weak. Furthermore, this result was further verified by molecular simulation docking experiments, as shown in Fig. S5.

3.4. Feasibility of the logic-gated detection strategy

PAGE was carried out to investigate whether the fabricated DTMS can recognize and hybridize with the ORF1ab and N genes of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA genome. As seen in Fig. 2B, the bands in lane 1 and lane 2 were ORF1ab and N gene, respectively. The bands in lane 3 and lane 4 corresponded to the DNA strands before and after the formation of DTMS. When the ORF1ab and N genes were introduced in the solution containing fabricated DTMS, a new product (ORF1ab-DTMS-N gene) generated, leading to that a much slower migration of band in lane 5 was observed. It is noteworthy that only one bright band can be seen in lane 5, probably because the ORF1ab and N gene preferentially hybridizes with the same DTMS. The results proved that we have successfully constructed a DTMS which could be applied to the logic-gated detection of the ORF1ab and N genes of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA genome.

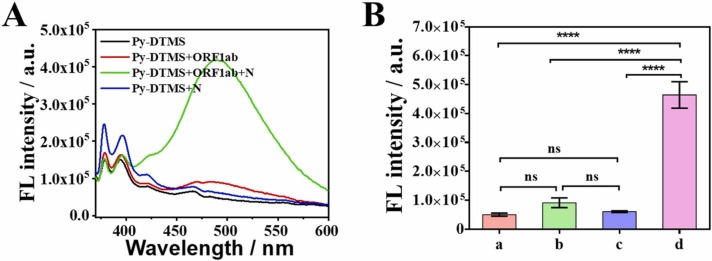

Fluorescence method was employed to examine the validity of the detection strategy. To this end, two pyrene fluorophores were labeled at the terminals of DTMS (termed Py-DTMS). The results in Fig. 3 A and 3B exhibited that the absence of the ORF1ab or N gene of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA genome resulted in a negligible change in fluorescence intensity, which is ascribed to that pyrene excimer emission cannot occur due to the slight change of Py-DTMS structure. When the ORF1ab and N genes of SARS-CoV-2 RNA genome were simultaneously present, intramolecular structure changes, inducing the generation of pyrene dimerization with the assistance of γ-CD. Consequently, a considerable pyrene excimer emission occurred. These results indicated that, the logic-gated strategy was successfully constructed, and can respond to ORF1ab and N genes of SARS-CoV-2 RNA genome. Furthermore, the quantum yields (QYs) of ORF1ab-DMTS-N gene triplex complexes and Py-DTMS were evaluated by using quinine sulfate (54%) as a reference standard (Table S2). According to the absorbance and fluorescence intensity as shown in Fig. S6A-C and Table S2, the QYs of ORF1ab-DMTS-N gene triplex complexes reache up to 22.73%, compare with 2.61% for Py-DTMS.

Fig. 3.

(A) Fluorescence emission spectra of Py-labeled DTMS (black); Py-DTMS + N gene (blue); Py-DTMS + ORF1ab gene (red); Py-DTMS + N gene + ORF1ab gene (green) in the phosphate buffer saline. (B) The fluorescence intensity at 490 nm which from a to d: Py-DTMS; Py-DTMS + N gene; Py-DTMS + ORF1ab gene; Py-DTMS + ORF1ab + N gene. The concentrations of Py-DTMS, N gene and ORF1ab gene were 100 nM. Error bars stand for SD (n = 3). * , P < 0.05, * *, P < 0.01, * ** , P < 0.001, * ** *, P < 0.0001; ns, not signifificant.

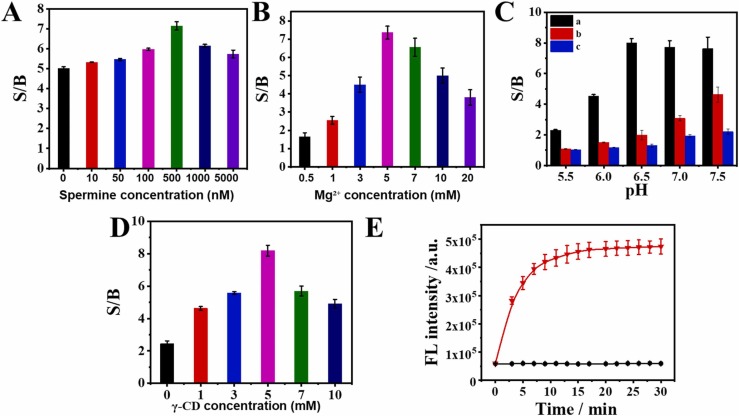

3.5. Optimization of experiment conditions

To maximize the performance of the DTMS-based detection strategy, a series of experimental conditions were explored successively. At first, the concentrations of spermine and Mg2+, and pH value are highly associated with the stability of the fabricated DTMS. As shown in Fig. 4A, the signal-to-background ratio (S/B) increased continuously with the ascending concentration of the spermine and reached the peak at 500 nM, which was fixed as an appropriate concentration. Similarly, the concentration of Mg2+ was optimized at 5 mM (Fig. 4B). For the optimization of pH value, the single presence of the ORF1ab or N gene was set as the control. As shown in Fig. 4C, the S/B increased gradually with the rising pH value, thereafter kept steady after 6.5, upon the addition of ORF1ab and N gene, precisely because the DTMS is too stable to be opened by ORF1ab and N gene at low pH (5.5), while the deconstruction of the triplex configuration occurred at high pH (7.5). However, the S/B only presented an uprising trend from 5.5 to 7.5 in the single presence of the ORF1ab or N gene. Thus, to guarantee the smooth response to the target ORF1ab and N gene as well as reduce the impact from the single target gene, 6.5 was appointed as an optimal pH value. In addition, γ-CD can wrap the pyrene molecule via an affinity function, thus enhancing the fluorescence of dimer pyrene molecule by the hydrophobic environment in the cavity and the stability of dimer pyrene [31]. Therefore, we assess the impact of γ-CD concentration on the performance of the detection strategy. As seen in Fig. 4D, S/B underwent an increasing trend with an exceeded concentration of 5 mM, which was chosen for further experiments. Ultimately, the reaction time of DTMS with target ORF1ab and N gene was evaluated and the results were depicted in Fig. 4E. The fluorescence signal increased gradually when the reaction time was prolonged from 0 min to 30 min and almost reached peak value at 20 min, which was chosen as an appropriate condition.

Fig. 4.

Optimization of experiment conditions. Concentrations of Spermidine (A), Mg²⁺ (B), γ-CD (C); (D) pH value; a: Py-DTMS + ORF1ab + N gene, b: Py-DTMS + N gene, c: Py-DTMS + ORF1ab. (E) hybridization time of DTMS with ORF1ab gene and N gene. Error bars stand for SD (n = 3).

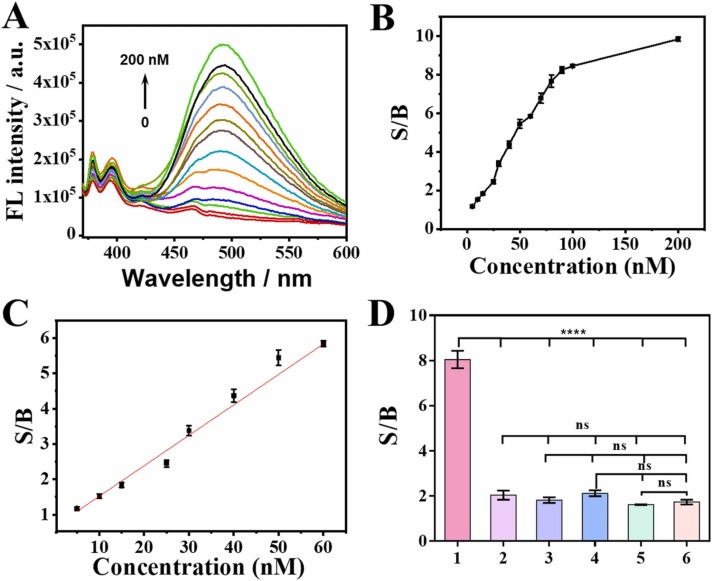

3.6. Quantification of SARS-CoV-2 RNA

Under the optimized experimental conditions, the detection performance of the proposed logic-gated strategy toward ORF1ab and N genes of SARS-CoV-2 RNA was evaluated. As depicted in Fig. 5A, the fluorescence signal at 490 nm gradually increased upon the addition of various concentrations of ORF1ab and N genes from 0 to 200 nM, along with a constantly ascending S/B (Fig. 5B). Additionally, an excellent linear relationship between the S/B values and target concentrations ranging from 0 to 60 nM, could be observed in Fig. 5C. The regression equation is determined as yS/B = 0.08623 C target + 0.66088 (R² = 0.99), and the detection limit was calculated to be 1.3 nM by 3σ/slope. These corroborated results clearly indicate that the Py-DTMS showed a good response to ORF1ab and N genes.

Fig. 5.

(A) Fluorescence emission spectra of Py-DTMS in the presence of increasing concentrations of ORF1ab and N genes. The arrow indicates the signal changes with increases in target concentrations (0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, 100, and 200 nM). (B) S/B of Py-DTMS in the presence of increasing concentrations of ORF1ab and N genes. (C). The linear relationship between the S/B value and the concentration of targets ranges from 0 to 60 nM. (D) The S/B value of Py-DTMS response to different combinations of targets. The concentrations of Py-DTMS and targets were 100 nM. From 1–6: ORF1ab + N genes;M + N gene;S + ORF1ab;S + N gene;M + ORF1ab;M + S. The above experiments were all performed in the phosphate buffer saline (500 nM Spermine, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM γ-CD, pH 6.5), and the reaction time was 20 min. Error bars stand for SD (n = 3). * , P < 0.05, * *, P < 0.01, * ** , P < 0.001, * ** *, P < 0.0001; ns, not signifificant.

3.7. Specificity and practicability evaluation

Specificity is an important indicator to measure the performance of a biosensor. For this purpose, the nonhomologous M gene (M gene produces viral membranous glycoprotein) and nonhomologous S (S gene produces viral surface glycoproteins) was recruited as the interferences. Afterward, ORF1ab, N, M, and S were randomly combined with each other. As seen in Fig. 5D, only the combination of ORF1ab and N genes induced a dramatical S/B value, while other combinations displayed a negligible difference, demonstrating a desirable specificity of the logic-gated SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection strategy.

Furthermore, to assess the practicability of the proposed strategy toward SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection, oropharyngeal swab saliva was used as the real sample and injected into equal concentrations of ORF1ab and N genes. Then, these samples were allowed to react with Py-DTMS, followed by fluorescence measurement. The recoveries ranged from 94.5% to 103.2% ( Table 1), demonstrating excellent practicability of the logic-gated SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection strategy.

Table 1.

The recovery rate of Py-DTMS.

| Number | Spiked | Founda | Recovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5.00 + 5.00 | 5.08 ± 0.22 | 101.5% |

| 2 | 10.00 + 10.00 | 9.77 ± 0.12 | 97.7% |

| 3 | 15.00 + 15.00 | 14.73 ± 0.28 | 98.2% |

| 4 | 20.00 + 20.00 | 18.90 ± 0.42 | 94.5% |

| 5 | 25.00 + 25.00 | 25.80 ± 0.71 | 103.2% |

4. Conclusion

In summary, we proposed a DTMS-based, logic-gated strategy for high-fidelity SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection. The DTMS is capable of recognizing and binding ORF1ab and N genes of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA genome simultaneously. The coexisting Orf1ab and N genes can induce a structural rearrangement of DTMS, thereby bringing the two pyrenes into spacer proximity and leading to a new signal readout. This strategy allows the detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA with a detection limit of 1.3 nM. Additionally, this logic-gated strategy is independent of nucleic acid amplification and elaborates to design, thus steering clear of undesirable cross-reaction and guaranteeing the detection accuracy. We speculate that the DTMS will be an alternative indicator probe for screening COVID-19 and other population-wide epidemics.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ting Chen: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Pengfei Liu: Methodology, Investigation, Writing- original draft. Huanxiang Wang: Methodology, Investigation, Software, Visualization. Yue Su: Software. Sheng Li: Investigation. Shimeng Ma: Investigation. Xuan Xu: Resources. Jie Wen: Resources. Zhen Zou: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Data curation.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21705010, 21735001, 21605008, 91853104), Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (2022JJ20038, 2019JJ50653, 2020JJ4409), the Scientific Research Fund of Hunan Provincial Education Department (20B032), and Natural Science Foundation of Changsha City (kq2202189).

Biographies

Ting Chen is presently pursuing his master degree in Chemistry in Hunan Normal University. Her current research focuses on triplex nucleic acid probe and their applications in cancer cell research and metastasis, and treatment of cancer.

Pengfei Liu is presently pursuing his doctor degree in Chemistry in Hunan Normal University. His current research focuses on triplex nucleic acid probe and CRISPR/Cas systems.

Huanxiang Wang acquired master degree in Chemistry in Changsha University of Science and Technology in 2021. His former research focuses on Nucleic acid probes and its application in biological detection.

Yue Su is presently pursuing his master degree in Chemistry in Hunan Normal University. His current research interests include construction of nucleic acid nanoparticles and their chemical and biological applications.

Sheng Li is presently pursuing his master degree in Chemistry in Hunan Normal University. Her main research interest regards triplex nucleic acid probe for cancer therapy and drug evaluation.

Shimeng Ma is presently pursuing his bachelor degree in Chemistry in Hunan Normal University. Her research interests include construction and properties of triplex nucleic acid probe.

Xuan Xu is a professor of Hunan Provincial Peoples’ Hospital, The First Affiliated Hospital of Hunan Normal University. His current research interests include gene analysis and nanobiomedical.

Jie Wen received his Ph.D. degree from Fudan University. He is currently working at Hunan Provincial Peoples’ Hospital, The First Affiliated Hospital of Hunan Normal University. His current research interests include biomarker analysis and nanobiomedical.

Zhen Zou received his Ph.D. degree from Hunan University. He is currently working at Hunan Normal University and Changsha University of Science and Technology. His current research interests include biochemical analysis based on triplex molecular switch.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.snb.2022.132579.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

.

Data Availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Ferretti L., Wymant C., Kendall M., Zhao L., Nurtay A., Abeler-Dörner L., Parker M., Bonsall D., Fraser C. Quantifying SARS-CoV-2 transmission suggests epidemic control with digital contact tracing. Science. 2020;368:eabb6936. doi: 10.1126/science.abb6936. 〈https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.abb6936〉 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheong J.Y., Yu H.J., Lee C.Y., Lee J., Choi H.J., Lee J.H., Lee H., Cheon J. Fast detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA via the integration of plasmonic thermocycling and fluorescence detection in a portable device. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2020;4:1159–1167. doi: 10.1038/s41551-020-00654-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang C., Horby P.W., Hayden F.G., George F.G. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet. 2020;395:470–473. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30185-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/ S0140-6736(20)30185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu N., Zhang D.Y., Wang W.L., Li X.W., Yang B., Song J.D., Zhao X., Huang B.Y., Shi W.F., Lu R.J., Niu P.H., Zhan F.X., Ma X.J., Wang D.Y., Xu W.B., Wu G.Z., Gao G.F., Tan W.J. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rothe C., Schunk M., Sothmann P., Bretzel G., Froeschl G., Wallrauch C., Zimmer T., Thiel V., Janke C., Guggemos W., Seilmaier M., Drosten C., Vollmar P., Zwirglmaier K., Zange S., Wölfel R., Hoelscher M. Transmission of 2019-nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in germany. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:970–971. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Broughton J.P., Deng X.D., Yu G., Fasching C.L., Servellita V., Singh J., Miao X., Streithorst J.A., Granados A., Gonzalez A.S., Zorn K., Gopez A., Hsu E., Gu W., Miller S., Pan C.Y., Guevara H., Wadford D.A., Chen J.S., Chiu C.Y. CRISPR-Cas1-based detection of SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020;38:870–874. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0513-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bai Y., Yao L.S., Wei T., Tian F., Jin D.Y., Chen L.J., Wang M.Y. Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323:1406–1407. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He X., Lau E.H.Y., Wu P., Deng X.L., Wang J., Hao X.X., Lau Y.C., Wong J.Y., Guan Y.J., Tan X.H., Mo X.N., Chen Y.Q., Liao B.L., Chen W.L., Hu F.Y., Zhang Q., Zhong M.Q., Wu Y.R., Zhao L.,Z., Zhang F.,C., Cowling B.J., Li F., Leung G.M. Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2020;26:672–675. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0869-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Service R.F. Fast, cheap tests could enable safer reopening. Science. 2020;369:608–609. doi: 10.1126/science.369.6504.608. 〈htts://www.science.or/doi/10.1126/science.369.6504.6〉 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li R.Y., Pei S., Chen B., Song Y.M., Zhang T., Yang W., Shaman J. Substantial undocumented infection facilitates the rapid dissemination of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) Science. 2020;368:489–493. doi: 10.1126/science.abb3221. 〈https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.abb3221〉 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morris T., Robertson B., Gallagher M. Rapid reverse transcription-PCR detection of hepatitis C virus RNA in serum by using the TaqMan fluorogenic detection system. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1996;34:2933–2936. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.12.2933-2936.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Udugama B., Kadhiresan P., Kozlowski H.N., Malekjahani A., Osborne M., Li V.Y., Chen H., Mubareka S., Gubbay J.B., Chan W.C. Diagnosing COVID-19: The disease and tools for detection. ACS Nano. 2020;14:3822–3835. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c02624. https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acsnano.0c02624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patchsung M., Jantarug K., Pattama A., Aphicho K., Suraritdechachai S. Clinical validation of a Cas13-based assay for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2020;4:1140–1149. doi: 10.1038/s41551-020-00603-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vogels C.B., Brito A.F., Wyllie A.L., Joseph R.F., Isabel M.O. Analytical sensitivity and efficiency comparisons of SARS-CoV-2 RT-qPCR primer-probe sets. Nat. Microbiol. 2020;5:1299–1305. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0761-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu H.P., Wang H., Shi Z.Y., Wang H., Yang C.Y., Silke S., Tan W.H., Lu Z.H. TaqMan probe array for quantitative detection of DNA targets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34 doi: 10.1093/nar/gnj006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kalinina O., Lebedeva I., Brown J., Silvr J. Nanoliter scale PCR with TaqMan detection. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:1999–2004. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.10.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Y.L., Zhang D.B., Li W.Q., Chen J.Q., Peng Y.F., Cao W. A novel real-time quantitative PCR method using attached universal template probe. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;31 doi: 10.1093/nar/gng123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suri T., Mittal S., Tiwari P., Mohan A., Hadda V., Madan K., Guleria R. COVID-19 real-time RT-PCR: Does positivity on follow-up RT-PCR always imply infectivity? Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care. 2020;202:147. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202004-1287LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han M.S., Byun J., Rim Y.J.H. RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2: quantitative versus qualitative. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20:697–706. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30424-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lan L., Xu D., Ye G.M., Xia C., Wang S.K., Li Y.R., Xu H.B. Positive RT-PCR test results in patients recovered from COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323:1502–1503. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wyllie A.L., Premsrirut P.K. Saliva RT-PCR sensitivity over the course of SARS-CoV-2 infection. JAMA. 2022;327:182–183. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.21703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yan S.J., Ahmad K.Z., Warden A.R., Ke Y.Q., Maboyi N., Zhi X., Ding X.T. One-pot pre-coated interface proximity extension assay for ultrasensitive co-detection of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and viral RNA. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021;193 doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2021.113535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tian T., Shu B., Jiang Y.Z., Ye M.M., Liu L., Guo Z.H., Han Z.P., Wang Z., Zhou X.M. An ultralocalized Cas13a assay enables universal and nucleic acid amplification-free single-molecule RNA diagnostics. ACS Nano. 2021;15:1167–1178. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c08165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yue H., Shu B., Tian T., Xiong E.H., Huang M.Q., Zhu D.B., Sun J., Liu Q., Wang S.C., Li Y.R., Zhou X.M. Droplet Cas12a assay enables DNA quantification from unamplified samples at the single-molecule level. Nano Lett. 2021;21:4643–4653. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.1c00715. htts://doi.or/10.1021/acs.nanolett.1c00715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng J., Li J.S., Jiang Y., Jin J.Y., Wang K., Yang R.H., Tan W.H. Design of aptamer-based sensing platform using triple-helix molecular switch. Anal. Chem. 2011;83:6586–6592. doi: 10.1021/ac201314y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masuko M., Ohtani H., Ebata K., Shimadzu A. Optimization of excimer-forming two-probe nucleic acid hybridization method with pyrene as a fluorophore. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:5409–5416. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.23.5409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conlon P., Yang C.Y.J., Wu Y.R., Chen Y., Martinez K., Kim Y., Stevens N., Marti A.A., Jockusch S., Turro N.J., Tan W.H. Pyrene excimer signaling molecular beacons for probing nucleic acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:336–342. doi: 10.1021/ja076411y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Y., Hu Y.H., Wu T., Zhou X.S., Shao Y. Triggered excited-state intramolecular proton transfer fluorescence for selective triplex DNA recognition. Anal. Chem. 2015;87:11620–11624. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b02851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu S.S., Wang S., Zhao J.H., Sun J., Ya X.R. Classical triplex molecular beacons for microRNA-21 and vascular endothelial growth factor detection. ACS Sens. 2018;3:2438–2445. doi: 10.1021/acssensors.8b00996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sasaki Y., Miyoshi D., Sugimoto N. Regulation of DNA nucleases by molecular crowding. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:4086–4093. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li N., Qi L., Qiao J., Chen Y. Ratiometric fluorescent pattern for sensing proteins using aqueous polymer-pyrene/γ-cyclodextrin inclusion complexes. Anal. Chem. 2016;88:1821–1826. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b04112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.