Abstract

Growth experiments with Escherichia coli have shown that this organism is able to use allantoin as a sole nitrogen source but not as a sole carbon source. Nitrogen assimilation from this compound was possible only under anaerobic conditions, in which all the enzyme activities involved in allantoin metabolism were detected. Of the nine genes encoding proteins required for allantoin degradation, only the one encoding glyoxylate carboligase (gcl), the first enzyme of the pathway leading to glycerate, had been identified and mapped at centisome 12 on the chromosome map. Phenotypic complementation of mutations in the other two genes of the glycerate pathway, encoding tartronic semialdehyde reductase (glxR) and glycerate kinase (glxK), allowed us to clone and map them closely linked to gcl. Complete sequencing of a 15.8-kb fragment encompassing these genes defined a regulon with 12 open reading frames (ORFs). Due to the high similarity of the products of two of these ORFs with yeast allantoinase and yeast allantoate amidohydrolase, a systematic analysis of the gene cluster was undertaken to identify genes involved in allantoin utilization. A BLASTP search predicted four of the genes that we sequenced to encode allantoinase (allB), allantoate amidohydrolase (allC), ureidoglycolate hydrolase (allA), and ureidoglycolate dehydrogenase (allD). The products of these genes were overexpressed and shown to have the predicted corresponding enzyme activities. Transcriptional fusions to lacZ permitted the identification of three functional promoters corresponding to three transcriptional units for the structural genes and another promoter for the regulatory gene allR. Deletion of this regulatory gene led to constitutive expression of the regulon, indicating a negatively acting function.

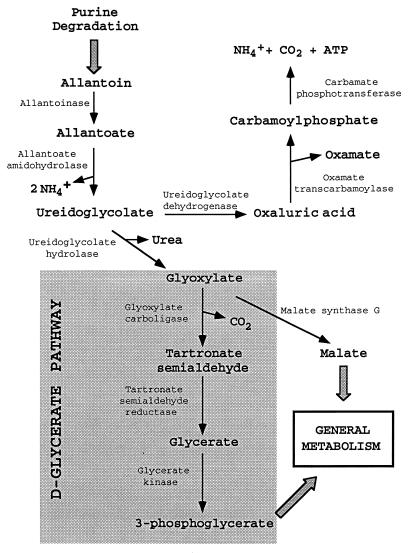

Utilization of allantoin as a nitrogen source by Escherichia coli and other Enterobacteriaceae was first suggested by Vogels and van der Drift in a review of the degradation of purines and pyrimidines by microorganisms (26). The proposed pathway (Fig. 1) opens the allantoin ring, R-(−) or S-(+) stereoisomer, yielding allantoate by the action of the hydrolase RS-allantoinase. Allantoate is converted to ureidoglycine, NH4+, and CO2, and ureidoglycine is converted to ureidoglycolate and NH4+ by the sequential action of the enzyme allantoate amidohydrolase (28). Ureidoglycolate is a substrate of two different enzymes, ureidoglycolate hydrolase, which converts it to urea and glyoxylate, and ureidoglycolate dehydrogenase, which oxidizes it to oxaluric acid. Glyoxylate is incorporated into the general metabolism through the glycerate pathway. This central pathway requires the action of glyoxylate carboligase, which forms tartronic semialdehyde; tartronic semialdehyde reductase, which converts the semialdehyde into glycerate; and glycerate kinase, which forms the glycolytic intermediate 3-phosphoglycerate (17). The conversion of oxaluric acid into oxamate and carbamoyl phosphate by the action of oxamate transcarbamoylase activity has been reported for E. coli (23). Carbamoyl phosphate is subsequently converted to CO2, NH4+, and ATP. The values of the fermentation balance obtained by Barker (2) are consistent with the proposed pathway (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Metabolic map of the pathway for the degradation of allantoin in Enterobacteriaceae.

Chang et al. (6), in their examination of enzymes of the acetohydroxy acid synthase family, have studied glyoxylate carboligase and reported the sequence and location of the corresponding gene at centisome 12 on the E. coli map. However, the locations of the genes for the other two enzymes of the glycerate pathway remain unknown.

In this report, we characterize and map the genes encoding tartronic semialdehyde reductase and glycerate kinase and show that they are clustered with genes involved in the anaerobic utilization of allantoin. The gene products of this cluster are identified, as is a related regulator.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

All the strains used were E. coli K-12 derivatives. The relevant genotypes and sources of these bacterial strains are given in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this work

| Strain | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| XL1Blue | recA1 lac endA1 gyrA96 thi hsdR17 supE44 relA1 (F′ proAB lacIqlacZΔM15 Tn10) | Stratagene |

| ECL1 | HfrC phoA8 relA1 tonA22 T2r (λ) | 12 |

| JC7623 | arg thi thr leu pro his strA recB21 recC22 sbcB15 | 27 |

| TE2680 | F− λ− IN(rrnD-rrnE) ΔlacX74 rplS galK2 recD::Tn10d-tet trpDC700:: putA13033::(Kanr Cmrlac) | 7 |

| JA170 | ECL1 glxK::Tn5 | This work |

| JA171 | ECL1 glxR::Tn5 | This work |

| JA172 | ECL1 gcl::Tn5 | This work |

| JA173 | ECL1 ΔallR | This work |

| JA174 | ECL1 allA::cat | This work |

| EcoR26 | Human feces isolate | 16 |

| EcoR36 | Human urine isolate | 16 |

| EcoR45 | Pig isolate | 16 |

Cell growth.

Cells were grown and harvested as described previously (4). For aerobic growth, carbon sources were added to a basal inorganic medium (4) at a 60 mM carbon concentration; for anaerobic growth, 120 mM was used. Casein acid hydrolysate was prepared at 1% for the aerobic growth of transformed cells. In these minimal media, the nitrogen source was ammonium sulfate (4), except when the nitrogen source was allantoin, which was added at a 60 mM concentration. To avoid hydrolysis, the allantoin medium was freshly prepared by dissolving allantoin in mineral medium and sterilizing the solution by filtration. When required, the following antibiotics were used at the indicated concentrations: ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; tetracycline, 12.5 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 30 μg/ml; and kanamycin, 50 μg/ml. 5-Bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactoside (X-Gal) and isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside were used at 30 and 10 μg/ml, respectively. For β-galactosidase assays, cultures were allowed to double five or six times during mid-log phase to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.5 for aerobic cultures or 0.25 for anaerobic cultures.

Preparation of cell extracts and enzyme assay.

Cells were harvested at the end of exponential phase, and a cell extract was prepared as described previously (4) with 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.3). EDTA and β-mercaptoethanol were added to the allantoate amidohydrolase or tartronic semialdehyde reductase assay mixtures to final concentrations of 1 and 10 mM, respectively.

Glyoxylate carboligase was assayed by measuring the production of 14CO2 from [1,2-14C]glyoxylate (specific activity, 0.45 μCi/μmol) by a modification of the method of Chang et al. (6); phenylethylamine was used instead of methylbenzethonium hydroxide in the central well of the reaction vial to collect the radioactive CO2.

Tartronic semialdehyde reductase was assayed by coupling this activity to purified glyoxylate carboligase and measuring the decrease in NADH with glyoxylate as a substrate. The reaction mixture (1 ml) contained 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0), 6 mM glyoxylate, 0.28 mM NADH, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM thiamine diphosphate, and an excess amount (2.5 U) of glyoxylate carboligase purified as described by Chang et al. (6).

Glycerate kinase activity was determined from the rate of NADH oxidation in the presence of 2 mM d-glycerate, 2 mM ATP, 0.35 mM reduced glutathione, 3.5 mM MgCl2, 0.28 mM NADH, a pyruvate kinase–l-lactate dehydrogenase mixture (18 μg/ml), and 1.75 mM phosphoenolpyruvate (1).

Allantoinase was assayed by the colorimetric method described by Lee and Roush (11) applied to the reaction of the allantoate product with phenylhydrazine HCl and potassium ferricyanide. Allantoate amidohydrolase was assayed by measuring ureidoglycolate production as described by Xu et al. (28). Ureidoglycolate production was determined by differential analyses of glyoxylate derivatives (25).

Ureidoglycolate hydrolase activity was determined by measuring the production of glyoxylate through its reaction with phenylhydrazine as described by Pineda et al. (18). Ureidoglycolate dehydrogenase was in turn assayed by measuring the reduction of NAD associated with the oxidation of the substrate by the procedure described by van der Drift et al. (24).

In all the above indicated determinations, 1 U was defined as the amount of enzyme converting 1 μmol of substrate per min.

β-Galactosidase activity was measured by the hydrolysis of o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside and expressed in Miller units (15). Values reported are representative of at least three separate experiments performed in duplicate. Protein concentrations were determined by the method of Lowry et al. (14) with bovine serum albumin as a standard.

DNA manipulation.

Bacterial genomic DNA was obtained as described by Silhavy et al. (21). Plasmid DNA was routinely prepared by the boiling method (9). For large-scale preparation, a crude DNA sample was passed over a column (Qiagen GmbH, Düsseldorf, Germany). DNA manipulations were performed essentially as described by Sambrook et al. (19). The gene mapping membrane (Takara Shuzo Biomedicals) containing the immobilized DNA of the entire Kohara λ phage bank was hybridized as follows. The membrane was first prehybridized at 65°C with salmon DNA in 6× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)–5× Denhardt solution–0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate. After 3 h, 100 μl of TE buffer containing 15 × 106 cpm of the probe, 32P labeled by the random-priming method, was added, and hybridization was maintained for 16 h. The filter was rinsed for three periods of 15 min each with 2× SSC, the last rinse also containing 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate. The dried filter was used to detect specific hybridization by autoradiography at −70°C.

The DNA sequence was determined by the dideoxy chain termination procedure of Sanger et al. (20) with double-stranded plasmid DNA as the template.

Mutagenesis and genetic techniques.

Tn5 insertion mutagenesis was carried out by infection with phage λ467 (b221 cIts857 rex::Tn5 Oam29 Pam80) as described by Bruijn and Lupski (5). Phage P1 transduction experiments were performed as described by Miller (15). The chloramphenicol resistance gene cassette CAT19 was used in the gene inactivation experiments (8, 27) by insertion into the restriction sites indicated below. Plasmids carrying inactivated genes were linearized and used to transform strain JC7623 to chloramphenicol resistance (Cmr). This strain efficiently recombines linear DNA into its chromosome (27). P1 vir lysates obtained from the selected Cmr recombinants were used to transduce the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) insertions into the parental strain ECL1. Precise in-frame tagged deletions were generated by crossover PCR (13).

To construct the 759-bp deletion of open reading frame (ORF) o271, the following set of oligonucleotide primers was used: o271-No, 5′-GGTGGATCCGATGTTGTTCTCTTAAGG-3′; o271-Ni, 5′-CCCATCCACTAAACTTAAACACCGTCTAACTTCCGTCATAC-3′; o271-Co, 5′-CGCGGATCCGACCAGAACGCATCAGGTG-3′; and o271-Ci, 5′-TGTTTAAGTTTAGTGGATGGGGATATCAGCACGGCGTTGGG-3′. The fragment containing the deletion was then cloned into the BamHI site of vector pKO3, a gene replacement vector that contains a temperature-sensitive origin of replication and markers for positive and negative selection for chromosomal integration and excision. The deletion was introduced into the chromosome by use of the pKO3 gene replacement protocol described by Link et al. (13). Chromosomal insertions and deletions were confirmed by PCR.

Construction of lacZ fusions for identification of promoter sequences.

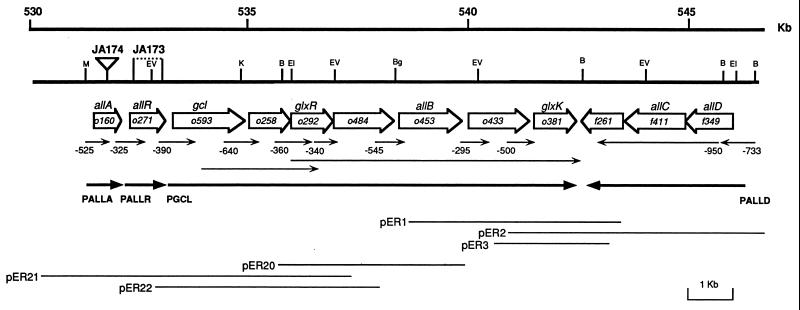

To create operon fusions, DNA fragments of the 5′ upstream region of each gene (Fig. 2) were cloned into plasmid pRS550 or pRS551 (22). In some experiments, the DNA fragment was extended to several genes to investigate the presence of possible promoters within the coding regions. The plasmids carried a promoterless lac operon and genes that confer resistance to both kanamycin and ampicillin. Recombinant plasmids were selected, after transformation of strain XL1Blue, as blue colonies on Luria-Bertani agar plates containing X-Gal, ampicillin, and kanamycin. Plasmid DNA was sequenced by use of an M13 primer to ensure that the desired fragment was inserted in the correct orientation. Merodiploids were obtained by transferring the fusions as single copies into the trp operon of E. coli TE2680 as described by Elliot (7). Transformants were selected for kanamycin resistance and screened for sensitivity to ampicillin and chloramphenicol. P1 vir lysates were made to transduce the fusions into strain ECL1.

FIG. 2.

Physical and genetic map of the region containing the genes involved in glycerate and allantoin metabolism. The thick lines represent the sequenced genomic fragment. The extension and direction of the included ORFs are indicated by open arrows and labeled by proposed gene symbols, according to determined function. Thin arrows correspond to the fragments fused to lacZ for testing promoter function and are labeled by numbers that indicate the length in nucleotides upstream of ATG. Thick arrows show the proposed transcriptional units labelled according to the promoter of the first transcribed gene. Thin lines correspond to the inserts of the clones used for the identification of the glycerate pathway genes. Relevant restriction sites are marked as follows: B, BamHI; Bg, BglII; EI, EcoRI; EV, EcoRV; K, KpnI; M, MluI.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Sequences determined in this study were deposited in GenBank under accession no. U89024 and U89279.

RESULTS

Utilization of allantoin as a nitrogen source.

Cultures of E. coli ECL1 placed on minimal medium plus allantoin did not grow either aerobically or anaerobically, indicating that these cells were unable to use this compound as a carbon source. In contrast, growth on minimal medium with xylose as a carbon source and allantoin instead of ammonium sulfate as a nitrogen source showed that these bacteria used allantoin as a sole nitrogen source only in the absence of oxygen. The doubling time of the anaerobic cultures was 6 h and was about one-third slower than that obtained with ammonium sulfate in the same carbon source. Studies on allantoin utilization were extended to several natural isolates of E. coli taken from the Selander collection (16), namely, strain EcoR45 from a pig, strain EcoR36 from human urine, and strain EcoR26 from human feces. All of them were able to utilize allantoin as a nitrogen source but not as a carbon source.

With the exception of oxamate transcarbamoylase (not tested due to the unavailability of a substrate), all activities involved in allantoin utilization, including those of the glycerate pathway, were measured with crude extracts of cells of strain ECL1 grown anaerobically on a xylose-ammonia or xylose-allantoin medium. All the required activities were found to be significantly higher when allantoin replaced ammonia in the cultures, thus giving support to the functional role of allantoin as a nitrogen source for cell growth (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Enzyme activities involved in the anaerobic utilization of allantoin for wild-type strain ECL1 and mutant strain JA173

| Enzyme | Activity (mU/mg) under the following growth conditions for the indicated strain:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xylose-NH4+

|

Xylose-allantoin

|

|||

| ECL1 | JA173 | ECL1 | JA173 | |

| Glyoxylate carboligase | 15 | 515 | 112 | 890 |

| Tartronic semialdehyde dehydrogenase | 5 | 175 | 40 | 310 |

| Glycerate kinase | 0 | 85 | 10 | 70 |

| Allantoinase | 0 | 20 | 27 | 520 |

| Allantoate amidohydrolaes | 0 | 10 | 13 | 320 |

| Ureidoglycolate dehydrogenase | 0 | 10 | 5 | 175 |

| Ureidoglycolate hydrolase | 0 | 4 | 3 | 9 |

Mapping of mutations in the glycerate pathway.

The biochemical relationship between allantoin metabolism and the glycerate pathway (Fig. 1), together with the ability to isolate glycerate pathway mutants, enticed us to study the location of the genes encoding the enzymes of this pathway as well as their possible linkage to the allantoin genetic system. The search for mutations in the glycerate pathway was approached by selecting mutants with defects in glyoxylate utilization. To this end, cells of wild-type strain ECL1 were mutagenized with transposon Tn5 and then selected for kanamycin resistance and the inability to utilize glyoxylate. From among 20 independent mutants tested for enzyme activities of the glycerate pathway, the following were selected: strain JA170, lacking glycerate kinase activity; strain JA171, lacking tartronic semialdehyde reductase activity; and strain JA172, lacking glyoxylate carboligase activity.

Mutations causing defects in tartronic semialdehyde reductase and glycerate kinase were used to map the corresponding genes, for which we propose the gene symbols glxR and glxK, respectively. Glyoxylate carboligase, encoded by gcl, was previously mapped by Chang et al. (6) at centisome 12 on the chromosome. A SauIIIA gene library of wild-type strain ECL1 was constructed on pBR322 and used to transform strain JA170. Clones were selected by growth on Luria-Bertani agar–ampicillin–kanamycin plates and replica plating on glyoxylate plates. Among 11 positive clones, 3 were characterized further (pER1 to pER3; Fig. 2). The restriction maps were determined, and plasmid DNA was used to transform strain JA170 to check glycerate kinase expression. All transformants displayed high glycerate kinase activity when grown on casein acid hydrolysate in the presence of 15 mM glyoxylate.

A 1-kb SalI-BamHI fragment (Fig. 2) common to all clones was isolated, 32P labeled by the random-priming method, and used to hybridize a membrane containing DNA of all clones of the Kohara library (10) (Takara Shuzo Biomedicals). Two clones, 156(9E5) and 157(6E7), hybridized with the glxK probe. The 3-kb overlapping fragment between these two clones was, according to the Kohara map, coincident with the physical map of the clones expressing glycerate kinase activity, allowing us to locate the glxK gene at centisome 11.7 on the chromosome map.

Likewise, strain JA171 was transformed with the gene library of strain ECL1, and several clones were isolated by phenotypic complementation of the tartronic semialdehyde reductase mutation. All transformants displayed high tartronic semialdehyde reductase activity when grown on casein acid hydrolysate in the presence of 15 mM glyoxylate. The restriction maps of three of the complementing plasmids (pER20 to pER22) showed some overlap with clones of the glycerate kinase complementation collection, indicating linkage between the two markers (Fig. 2). Furthermore, when cells of strain JA172 were transformed with DNA from plasmid pER22, which carried the glxR gene, and transformants were grown on casein acid hydrolysate in the presence of glyoxylate, the corresponding extracts also displayed high glyoxylate carboligase activity, thus proving that this clone carried both the glxR and the gcl genes.

Sequence of the gene cluster and gene organization.

Clustering of the three genes of the glycerate pathway and the presence between glxR and glxK of a gene encoding a product displaying high similarity to yeast allantoinase led us to search in this region for other genes encoding enzymes similar to those involved in the utilization of allantoin. A DNA region of 15.8 kb (Fig. 2) was totally sequenced by use of clones of the SauIIIA library, with the exception of an overlapping 2.3-kb internal fragment for glyoxylate carboligase and ORF o258 (GenBank accession no. L03845), the sequence of which had been published before (6). Analyses of the complete sequence permitted us to define the organization of the 12 ORFs indicated in Fig. 2. Subsequent availability of the sequences of this region (3) in the E. coli genome (GenBank project accession no. AE000156 and AE000157) allowed confirmation of the sequence identity as well as the deduced gene organization, with the exception of ORF o484. In the genome project, this region was proposed to contain two ORFs yielding proteins of 92 and 437 amino acids. However, on the basis of similarity to other permeases (see below), we assume that ORF o484 is functional for translation in vivo.

The amino acid sequences encoded by the unidentified ORFs were used as the query sequences for a BLASTP search of the GenBank database by use of the National Center for Biotechnology Information BLAST server. In this way, high similarity was found between the o160 product and ureidoglycolate hydrolase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the o484 product and yeast allantoin permease, the o453 product and yeast allantoinase, the o433 product and xanthine permease of Bacillus subtilis or uracil permease of Bacillus caldolyticus, and finally between the f349 product and several malate dehydrogenases. Likewise, with the ORF o271 sequence as a query sequence, the BLASTP search revealed similarity to regulatory proteins such as the glycerol activator (Streptomyces), the acetate repressor (E. coli), and the Kdg repressor involved in pectinolysis in Erwinia chrysanthemi, all belonging to the known IclR family. Finally, no similarity to any group of functional proteins was found for the products of ORFs o258 and f261.

Identification of gene products.

To determine if the functions suggested by the above analyses corresponded to actual protein activities, the following strategies were used. To confirm ureidoglycolate hydrolase as the product encoded by ORF o160 (proposed gene symbol allA), the gene was subcloned in plasmid pBlueScript and used to transform strain ECL1. Cell extracts of recombinant ECL1 harboring this plasmid showed the corresponding activity at about 10 times the level in wild-type E. coli, consistent with the suggestion that the protein expressed by allA was ureidoglycolate hydrolase. Furthermore, disruption of this gene by a CAT cassette inserted in the StuI restriction site and transfer of the mutant gene to the genome abolished the hydrolase activity in this mutant (strain JA174). Nevertheless, this mutation did not affect the rate of utilization of allantoin, as indicated by the normal growth of this mutant in xylose-allantoin medium. In contrast, the glycerate kinase-negative strain JA170 displayed poor growth when allantoin was used as a nitrogen source.

In parallel experiments, other genes were subcloned in pBlueScript, and their expression was analyzed. The results showed that gene o453 (proposed gene symbol allB) expressed high allantoinase activity, gene f411 (proposed gene symbol allC) expressed high allantoate amidohydrolase activity, and gene f349 (proposed gene symbol allD) expressed high ureidoglycolate dehydrogenase activity. All plasmid-encoded activities were between 10 and 15 times the activities in wild-type E. coli.

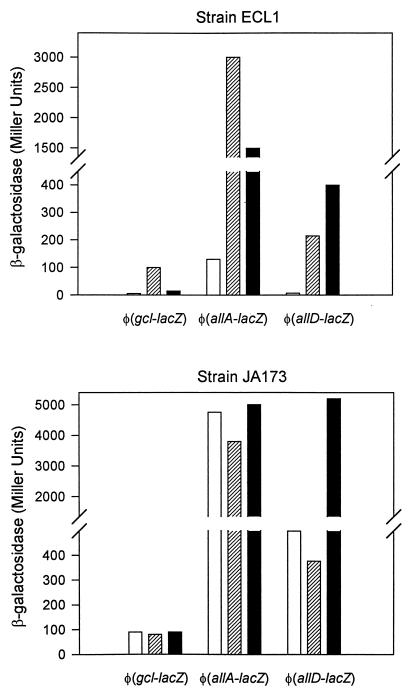

Analyses of functional promoters.

Identification of promoters in the gene cluster was performed by fusing to lacZ the 5′ end of each of the intervening genes. To check the presence of any promoter activity in this region, we tested two additional constructs: one lacking the gcl promoter but containing the genes gcl, o258, and glxR and the other containing the genes o484 to glxK. Cells of strain ECL1 containing the different gene fusions indicated in Fig. 2 were grown aerobically and anaerobically on minimal medium containing xylose plus glyoxylate. Expression was also studied by anaerobic growth on xylose with allantoin as a nitrogen source. Analysis of the different lacZ fusions revealed four promoters, corresponding to genes allA, allR (see below), gcl, and allD (Fig. 2). φ(allR-lacZ) showed constitutive expression whereas φ(allA-lacZ), φ(allD-lacZ), and φ(gcl-lacZ) showed inducible expression with glyoxylate and allantoin under anaerobic conditions (Fig. 3). Levels of enzyme specific activities under noninducing and inducing conditions matched rather well the pattern of operon expression (Table 2). Aerobically, glyoxylate was also able to induce the expression of φ(allA-lacZ) and φ(gcl-lacZ) but not φ(allD-lacZ).

FIG. 3.

β-Galactosidase activities of φ(gcl-lacZ), φ(allA-lacZ), and φ(allD-lacZ) transcriptional fusions in cells of strain ECL1 and strain JA173 grown anaerobically on d-xylose–NH4+ (open bars), d-xylose–glyoxylate (hatched bars), and d-xylose–allantoin (black bars).

Identification of the regulator.

ORF o271 (proposed gene symbol allR), whose product displayed similarity to the regulatory proteins indicated above, was deleted by crossover PCR, generating mutant strain JA173. In this mutant, the pattern of induction of the three promoter fusions corresponding to the structural genes was analyzed to determine the involvement and possible function of this gene in the allantoin system. All fusion constructs showed constitutive expression, as indicated by the levels of β-galactosidase activities in the absence of inducers. The lack of allR also caused the hyperinducibility of φ(allD-lacZ) by allantoin under anaerobic conditions. Constitutive levels of enzyme specific activities were also detected in extracts of anaerobically grown cells of strain JA173 under noninducing conditions (Table 2). Thus, the product encoded by allR corresponded to a negatively acting regulatory protein.

DISCUSSION

The utilization of purine bases and their derivatives as carbon or nitrogen sources in E. coli remains undefined, as no consistent information is found in the literature. In their review, Vogels and van der Drift (26) found important discrepancies in reports of the capacity of E. coli and other bacteria to use these nutrients for growth. Our results indicate that cells of E. coli are able to utilize allantoin as a nitrogen source only anaerobically. The noninducibility under aerobic conditions of the allD promoter, corresponding to the transcriptional unit encoding ureidoglycolate dehydrogenase and allantoate amidohydrolase, accounts for the inability to utilize allantoin as a nitrogen source aerobically. Concerning the metabolic roles shared between the two branches of the allantoin pathway, the observation of a normal utilization of allantoin in the absence of ureidoglycolate hydrolase indicates a predominant channeling of nitrogen through the branch of oxamate formation. Thus, impairment of allantoin utilization in glycerate kinase mutants must be explained by toxic effects of accumulated intermediate metabolites, such as glyoxylate, resulting from minor metabolic flow through the glycerate branch under anaerobic conditions.

Of the nine genes encoding the proteins required to convert allantoin to NH4+, CO2, urea, 3-phosphoglycerate, and oxamate, only the one encoding glyoxylate carboligase had been previously identified and mapped (6). There is a slight discrepancy in the kilobase scale between the maps of Kohara et al. (10) and the genome project (3), causing a difference in the locations of the genes of the cluster defined here. In the last and more precise map established by the genome project, the system lies between 531.5 and 546.3 kb, corresponding to centisomes 11.45 and 11.77, respectively. We have found good agreement between our proposal and that of the genome project in the assignment of the 12 ORFs, with two exceptions: (i) an alternative translation of ORF o484 into a protein of 92 amino acids followed by another of 437 amino acids, with the overlapping of 1 nucleotide; and (ii) a start for ORF o433 one codon upstream, converting it to o434, which is inconsistent with the location of the Shine-Dalgarno box. The similarity of the o484 product to other permeases of the family seems to indicate that the full-length translation is more likely and realistic than the reported split of the gene.

In spite of the multiple origins of the central intermediate metabolite glyoxylate, the substrate of the glycerate pathway, it is tempting to speculate that the genes of this pathway have evolved as part of the allantoin utilization system.

Under anaerobic conditions, allantoin activates the promoters at the 5′ ends of allA and allD, leading to the expression of ureidoglycolate hydrolase, allantoate amidohydrolase, and ureidoglycolate dehydrogenase. Allantoin also weakly induces the third operon (gcl), expressing, together with the genes of the glycerate pathway, low levels of allantoinase, thus allowing a basal metabolic flow of allantoin degradation. The function of ureidoglycolate hydrolase is to generate the intermediate glyoxylate, which in turn reinforces the weak activation of the gcl promoter by allantoin and thus allows efficient utilization of allantoin. Hyperinducibility of the allD promoter could correspond to the effects of another regulator of unknown location and which could be under the control of allR or simply compete with it for the same promoter sequences.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Eva Romaní for help in the characterization of the glycerate kinase mutants.

This work was supported by grant PB97-0920 from the Dirección General de Enseñanza Superior e Investigación Científica, Madrid, Spain, and by the help of the Comissionat per Universitats i Recerca de la Generalitat de Catalunya.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson R L, Wood W A. Pathway of xylose and l-lyxose degradation in Aerobacter aerogenes. J Biol Chem. 1962;237:296–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barker H A. Streptococcus allantoicus and the fermentation of allantoin. J Bacteriol. 1943;46:251–259. doi: 10.1128/jb.46.3.251-259.1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blattner F R, Plunkett III G, Bloch C A, Perna N T, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Vides J, Glasner J D, Rode C K, Mayhew G F, Gregor J, Davis N W, Kirkpatrick H A, Goeden M A, Rose D J, Mau B, Shao Y. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 1997;277:1453–1474. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boronat A, Aguilar J. Rhamnose-induced propanediol oxidoreductase in Escherichia coli: purification, properties, and comparison with the fucose-induced enzyme. J Bacteriol. 1979;140:320–326. doi: 10.1128/jb.140.2.320-326.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruijn F J, Lupski J R. The use of transposon Tn5 mutagenesis in the rapid generation of correlated physical and genetic maps of DNA segments cloned into multicopy plasmids. Gene. 1984;27:131–149. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90135-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang Y Y, Wang A Y, Cronan J E., Jr Molecular cloning, DNA sequencing, and biochemical analyses of Escherichia coli glyoxylate carboligase. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:3911–3919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elliot T. A method for constructing single-copy lac fusions in Salmonella typhimurium and its application to the hemA-prfA operon. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:245–253. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.1.245-253.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuqua W C. An improved chloramphenicol resistance gene cassette for site-directed marker replacement mutagenesis. BioTechniques. 1992;12:223–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holmes D S, Quigley M. A rapid boiling method for the preparation of bacterial plasmids. Anal Biochem. 1981;114:193–197. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90473-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kohara Y, Akiyama K, Isono K. The physical map of the whole E. coli chromosome: application for a new strategy for rapid analysis and sorting of a large genomic library. Cell. 1987;50:495–508. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90503-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee K W, Roush A H. Allantoinase assays and their application to yeast and soybean allantoinases. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1964;108:460–467. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(64)90427-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin E C C. Glycerol dissimilation and its regulation in bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1976;30:535–578. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.30.100176.002535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Link A J, Phillips D, Church G M. Methods for generating precise deletions and insertions in the genome of wild-type Escherichia coli: application to open reading frame characterization. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6228–6237. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.20.6228-6237.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lowry O H, Rosebrough N J, Farr A L, Randall R J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller J H. A short course in bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ochman H, Selander R K. Standard reference strains of Escherichia coli from natural populations. J Bacteriol. 1984;157:690–693. doi: 10.1128/jb.157.2.690-693.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ornston L N, Ornston M K. Regulation of glyoxylate metabolism in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1969;98:1098–1108. doi: 10.1128/jb.98.3.1098-1108.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pineda M, Piedras P, Cardenas J. A continuous spectrophotometric assay for ureidoglycolase activity with lactate dehydrogenase or glyoxylate reductase as coupling enzyme. Anal Biochem. 1994;222:450–455. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;174:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silhavy T J, Berman M L, Enquist L. Experiments with gene fusions. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simons R W, Houman F, Kleckner N. Improved single and multicopy lac-based cloning vectors for protein and operon fusions. Gene. 1987;53:85–96. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tigier H, Grisolia S. Induction of carbamyl-P specific oxamate transcarbamylase by parabanic acid in a Streptococcus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1965;19:209–214. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(65)90506-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Drift C, van Helvoort P E M, Vogels G D. S-Ureidoglycolate dehydrogenase: purification and properties. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1971;145:465–469. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(71)80006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vogels G D, van der Drift C. Differential analyses of glyoxylate derivatives. Anal Biochem. 1970;33:143–157. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(70)90448-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vogels G D, van der Drift C. Degradation of purines and pyrimidines by microorganisms. Bacteriol Rev. 1976;40:403–468. doi: 10.1128/br.40.2.403-468.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Winans S C, Elledge S J, Krueger J H, Walker G C. Site-directed insertion and deletion mutagenesis with cloned fragments in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1985;161:1219–1221. doi: 10.1128/jb.161.3.1219-1221.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu Z, de Windt F E, van der Drift C. Purification and characterization of allantoate amidohydrolase from Bacillus fastidiosus. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;324:99–104. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.9923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]