Abstract

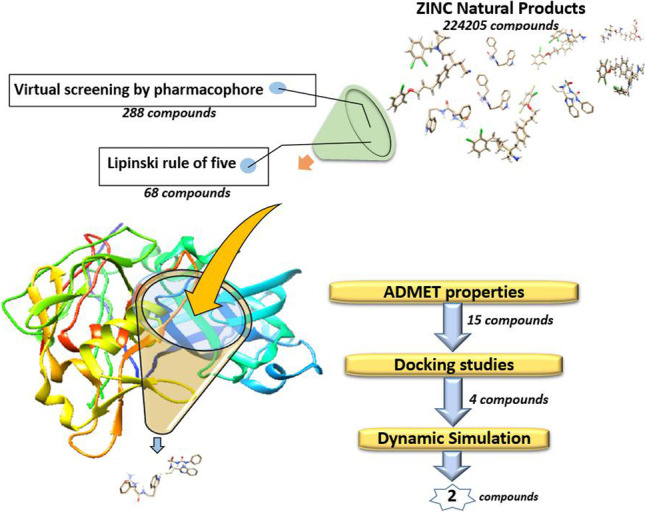

Main protease (Mpro) plays a key role in replication of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). This study was designed for finding natural inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro by in silico methods. To this end, the co-crystal structure of Mpro with telaprevir was explored and receptor-ligand pharmacophore models were developed and validated using pharmit. The database of “ZINC Natural Products” was screened, and 288 compounds were filtered according to pharmacophore features. In the next step, Lipinski’s rule of five was applied and absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) of the filtered compounds were calculated using in silico methods. The resulted 15 compounds were docked into the active site of Mpro and those with the highest binding scores and better interaction including ZINC61991204, ZINC67910260, ZINC61991203, and ZINC08790293 were selected. Further analysis by molecular dynamic simulation studies showed that ZINC61991203 and ZINC08790293 dissociated from Mpro active site, while ZINC426421106 and ZINC5481346 were stable. Root mean square deviation (RMSD), radius of gyration (Rg), number of hydrogen bonds between ligand and protein during the time of simulation, and root mean square fluctuations (RMSF) of protein and ligands were calculated, and components of binding free energy were calculated using the molecular mechanic/Poisson-Boltzmann surface area (MM/PBSA) method. The result of all the analysis indicated that ZINC61991204 and ZINC67910260 are drug-like and nontoxic and have a high potential for inhibiting Mpro.

Graphical abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00894-022-05286-6.

Keywords: Mpro, Natural inhibitor, Pharmacophore modelling, Docking, Molecular dynamic simulation

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) has caused significant social, economic, and political problems worldwide [1–3]. Caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), it has affected more than 526 million people (as of May 21, 2022) and about 6.3 million died from this disease (https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/). So far, several vaccines for COVID-19 have been developed by various pharmaceutical companies. Some of them have been authorized by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and are widely used in many countries which had a major impact on reducing mortality from the disease [4–6]. However, the epidemic will probably continue until the global launch of safe and effective vaccines to provide herd immunity. To date, symptomatic treatment and respiratory support are the main way of patient management for COVID-19 [7, 8]. Remdesivir is the only drug approved by the FDA to treat COVID-19 [9, 10]. Besides several side effects particularly liver inflammation, it is only prescribed for people who are hospitalized with COVID-19. Two other drugs including Baricitinib and Paxlovid were granted an emergency use authorization (EUA) by the FDA [11, 12]. Baricitinib is only used in hospitalized adults, and Paxlovid is a combination of nirmatrelvir and ritonavir and is used to treat early COVID-19 infection and help to prevent more severe symptoms [13–15]. Despite all efforts, efficient treatment of COVID-19 is still medically unmet, requiring further efforts, and the introduction of a suitable drug to treat this disease is still one of the main priorities.

Viral proteases play an essential role for the replication of many human pathogenic viruses by the cleavage of peptide bonds in viral polyprotein precursors [16]. Accordingly, many drugs have been developed to prevent viral progress by inhibiting the protease enzymes, like lopinavir and ritonavir that have been approved for the treatment of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) [17]. Two proteases are encoded by SARS-CoV-2 RNA genome including papain-like protease (PLpro) and main protease (also known as Mpro, chymotrypsin-like cysteine protease, 3C-like protease, and 3CLpro). Mpro is a cysteine protease (EC 3.4.22.69) that cleaves the coronavirus polyprotein precursor at eleven conserved sites [18]. P1 for this enzyme is a Gln and P1′ is a small residue like Ser, Aln, or Gly. Active site of this enzyme includes Cys145 and His41 residues which make a catalytic dyad in which His as a general base makes sulfur of the Cys a stronger nucleophile [19, 20]. Telaprevir is a protease inhibitor used for the treatment of hepatitis C [21, 22]. It was designed against hepatitis C virus NS3/4A protease [23]. Recently, it was shown that this compound is able to inhibit the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro activity with an IC50 value of 18 μM [24]. Some groups determined the crystal structure of Mpro in complex with telaprevir which provided an opportunity to develop structure based pharmacophore modeling for finding new inhibitors for Mpro [25–27].

Many anti-coronaviral compounds with natural sources have been identified in recent years [28]. The mechanism of action of these compounds varies from blocking of viral entry (tetra-O-galloyl-β-D-glucose and caffeic acid), inhibition of protein synthesis (silvestrol), inhibition of viral replication (myricetin) to inhibition of viral proteases (a number of flavonoids), and other mechanisms [29]. This study was designed for finding potential inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro among natural compounds by using structure-based pharmacophore modeling, molecular docking, and molecular dynamic simulation studies.

Materials and methods

Receptor-ligand pharmacophore generation

The co-crystal structure of Mpro with telaprevir was retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 7LB7; Resolution: 2.00 Å; R-value free: 0.225; and R-value work: 0.204) (www.rcsb.org) [25]. Analyzing the receptor–ligand interactions and defining the essential features of this interaction is the basis of structure-based pharmacophore modeling. The most important parts of the ligand that are responsible for ligand binding to the receptor are named pharmacophores. Pharmit (http://pharmit.csb.pitt.edu) is an online tool for structure-based pharmacophore modeling and virtual screening of large compound databases [30]. By providing protein–ligand complex, it will identify all pharmacophore features relevant to the protein–ligand interaction. Therefore, Mpro-telaprevir complex (7LB7) was loaded in Pharmit, and pharmacophoric features important in binding of telaprevir to Mpro were identified. At the first step, 20 pharmacophoric features important in Mpro-telaprevir interaction were detected by Pharmit. Then, 10 pharmacophore models with 4 to 6 features in each model were built. These models were used to screen actives and decoys libraries, and the model with the best results was selected for screening the natural compounds libraries.

Pharmacophore validation and virtual screening

Before using a pharmacophore model in virtual screening, it has to be validated. To this end, a set of previously described active compounds (Fig. S1) and a set of inactive or decoys for a specific target are required. A well-defined pharmacophore will detect the most numbers of active ligands and the least number of inactive or decoys [31]. By advanced literature search and UniProt (https://www.uniprot.org/), twenty-six chemically synthesized active inhibitors of Mpro were collected, which were docked with Mpro protein by using SwissDock server [32, 33].

Decoy compounds used for pharmacophore validation were obtained from DUD.E (http://dude.docking.org/) (accessed October 05, 2021) [34]. DUD-E is a database of thousands of active and decoy compounds for 102 targets. It can also make dozens of decoys per active ligand. Decoys are designed to have similar physicochemical properties to active ligands, but their 2-D topology is different.

Active and decoy compounds were uploaded in Pharmit as two separate libraries and were screened by using the generated pharmacophore models to see which model leads to the best result. Sensitivity and specificity (Eqs. (1) and (2)), the yield of actives (YA or recall), the enrichment factor (EF), and goodness of hit (GH) were calculated for each pharmacophore (Eqs. (3), (4), and (5)). The mentioned metrics were calculated using the following formulas [31, 35]:

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

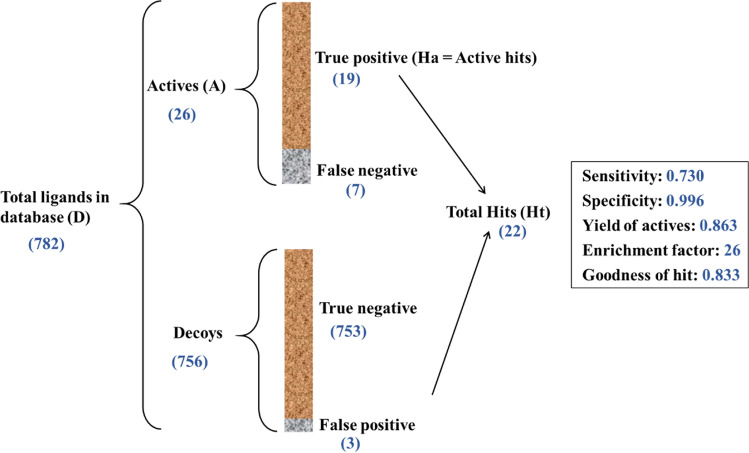

Figure 1 describes all the parameters used in these equations. YA (recall) is the percentage of true positives (Ha) in total hits (Ht). GH (goodness of hit) score is between 0 and 1, where better models have values close to 1. EF (enrichment factor) relates total hits (Ht) to the composition of the screening database. Higher EF indicates a better model [36].

Fig. 1.

Overall process and the result of pharmacophore validation

The best validated pharmacophore model (pharm_A) was saved as.json format in Pharmit and was used to screen “ZINC Natural Products” in ZINCPharmer. “ZINC Natural Products” is a library of 224,205 secondary metabolites found in bacteria, fungi, or plants. Compounds identified by pharmacophore virtual screening were prepared in structure data file (SDF) format to be used for Molecular docking study.

Drug-likeness Prediction

A set of basic molecular properties like molecular weight, number of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, and octanol/water partition coefficient (A log P) are determinant factors for a compound to make it a likely orally active drug in humans. There are some computational procedures for the prediction of these properties. In this study, SwissADME was used for calculation of these properties in the hit compounds [37]. SwissADME is a useful website that computes ADME parameters (absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion) as well as physicochemical properties and other descriptors of drug-like molecules. Lipinski’s rule of five was used to filter compounds. According to this rule, an orally active drug usually has no more than one violation of the following criteria: molecular weight (MW) ≤ 500 Da, number of hydrogen bond donors (HBDs) ≤ 5, number of H bond acceptors (HBAs) ≤ 10, and octanol/water partition coefficient (A log P) ≤ 5 [38]. These criteria were calculated in SwissADME and used for the filtration of the hit compounds.

ADMET calculation

Beside efficacy against the therapeutic target is of fundamental importance a good drug candidate compound should also have proper ADME properties including absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion [39]. Estimating ADME properties of compounds is of great importance in the process of hit identification and optimization. Therefore, the hits were investigated about their ADME properties by using swissADME [37]. Another important part of the drug discovery process is predicting the toxicity of compounds. ProTox-II was used to this end [40]. To further explain, ProTox-II is a virtual lab that enables prediction of several models of toxicities including, hepatotoxicity, carcinogenicity, immunotoxicity, mutagenicity, cytotoxicity, stress response pathways, and nuclear receptor signaling pathways.

Molecular docking study

Finding the best pose of each ligand in the binding site of the receptor and accurate calculation of its binding free energy is of great importance in the process of drug discovery. Therefore, the hit compounds selected from the previous steps were each docked separately into the binding site of Mpro by using SwissDock server. SwissDock uses docking software EADock DSS, whose algorithm for local docking is described as follow: At first, many binding modes are generated in a desired box determent by the user. Simultaneously, their CHARMM energies are estimated on a grid, and the binding modes with the most favorable energies are evaluated and clustered [32, 33]. Energy minimization of ligands was performed before docking by using Avogadro version 1.2.0 to remove clashes among atoms of the ligand and to develop a reasonable starting pose [41]. Universal force field (UFF) with steepest descent algorithm was used for minimization. Those compounds with appropriate binding free energy and orientation in the binding site were used for next rounds of docking. In this step, molecular dynamic simulation was performed on Mpro for 50 ns, and 3 different conformations from the trajectory were used to re-dock each compound to the binding site of Mpro. In the next step, a 100 ns molecular dynamic simulation was performed on all complexes resulting from docking to prove their stable binding to Mpro. Discovery studio visualizer 2016 (Accelrys Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) and UCSF Chimera 1.14 [42] were used for visualizing and interpreting ligand-receptor interactions.

Molecular dynamic simulation study

Molecular dynamic simulation of the selected protein–ligand complexes was done using Groningen machine for chemical simulations (GROMACS) 5.1.2 computational package which was installed in Ubuntu 18.04.5 LTS [43]. SwissParam server [44] was used for making topology files and other force field parameters for the selected compounds. To explain more, SwissParam is a server that can make topology and parameters for small organic molecules compatible with the CHARMM all atoms force field, for use with CHARMM and GROMACS. Protein topology file was made by using the pdb2gmx command and CHARMM27 all-atom force field (CHARM22 plus CMAP for proteins). “Gromacs format” (.gro) of ligand and protein was combined in Notepad + + , and topology file (.top) of the protein was edited, and “include topology” (.itp) parameters of ligand obtained from SwissParam were introduced to it. The protein–ligand complex (in.gro format) was centered in a cubic box, 1.0 nm from the box edge. The complex was solvated using water molecules represented using a simple point charge (SPC216) model. Four water molecules were replaced by Na + ions to neutralize the net negative charge of the protein and ensure the overall charge neutrality of the simulated system. Steepest descent minimization algorithm was used for the minimization of the system in a maximum number of 50,000 steps until the maximum force became less than 10.0 kJ/mol. For NVT, equilibration the v-rescale algorithm was used in 300 K with a coupling constant of 0.1 ps and time duration of 500 ps. The last phase in preparation of the system was NPT equilibration. In this step, Berenson pressure coupling algorithm with a coupling constant of 5.0 ps was applied for 1000 ps of NPT simulation. Particle-mesh Ewald (PME) algorithm was used for long-range electrostatics and cut-off method for van der Waals interactions. Cut off distances were set at 1.0 nm for the calculation of the electrostatic and 1.2 nm for van der Waals interactions. Finally, the compounds were subjected to three replica molecular dynamic simulations run of 100 ns per system.

Free binding energy calculations

After successful completion of molecular dynamic simulation, the protein–ligand complex was re-centered in the box, and analysis including calculation of root mean square deviation (RMSD), radius of gyration (Rg), number of hydrogen bonds in protein and between ligand and protein during the time of simulation, and root mean square fluctuations (RMSF) of protein and ligands was performed. Binding free energy calculation of protein–ligand complex was performed by using the g_mmpdsa program that was developed to calculate components of binding free energy using the molecular mechanic/Poisson-Boltzmann surface area (MM/PBSA) method. This program calculates components of binding energy of protein–ligand complex which can be described as

Two hundred snapshots were taken at an interval of 100 ps during the last 20 ns period of MD trajectory, and then binding energy calculations were performed.

Results and discussions

Structure bases pharmacophore modeling and virtual screening

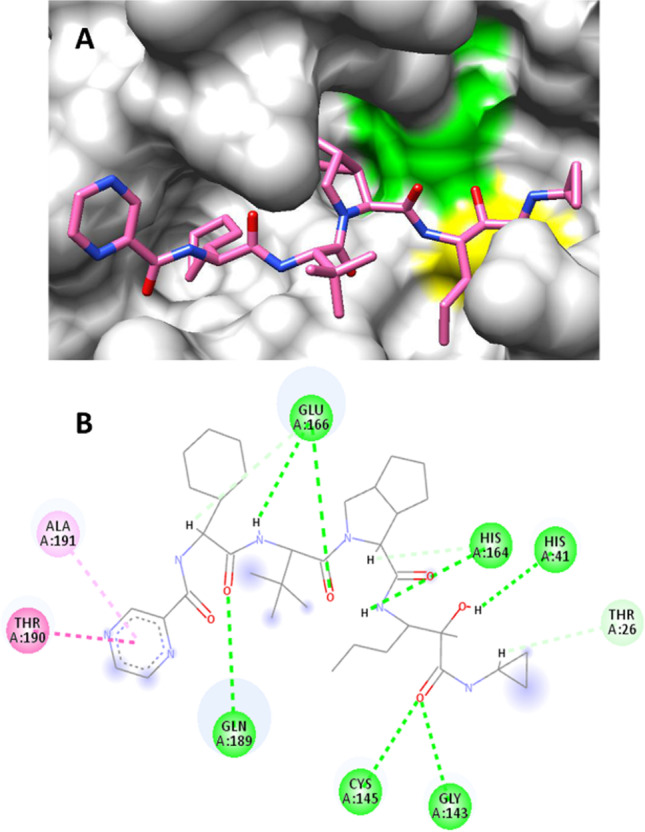

Non-bond interactions of telaprevir in the active site of Mpro are shown in Fig. 2. Telaprevir makes hydrogen bonds with both residues of the catalytic dyad including one hydrogen bond with Cys145 and one hydrogen bond with His41. Moreover, telaprevir makes two hydrogen bonds with Glu166 and one hydrogen bond with Gln189, Gly143, and His164. Hydrophobic interactions include one amide-Pi stacked with Thr190 and one Pi-alkyl with Ala191.

Fig. 2.

Orientation of telaprevir in complex with Mpro. His41 and Cys145, residues of the catalytic dyad, are depicted as green and yellow, respectively (A). Non-bond interactions of telaprevir in binding site of Mpro. Green, hydrogen bond; pink, amide-Pi stacked; light pink, Pi-alkyl; blue halo, solvent accessible surface (B)

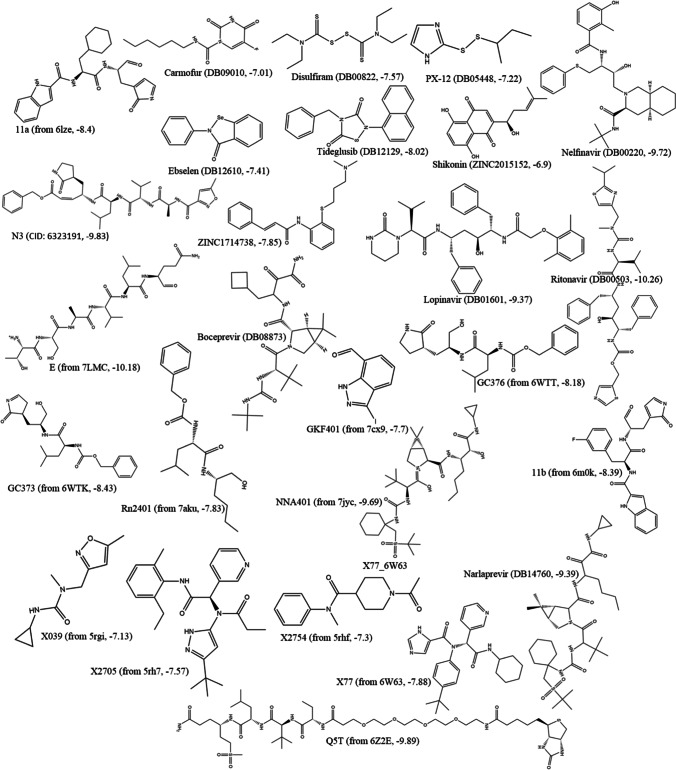

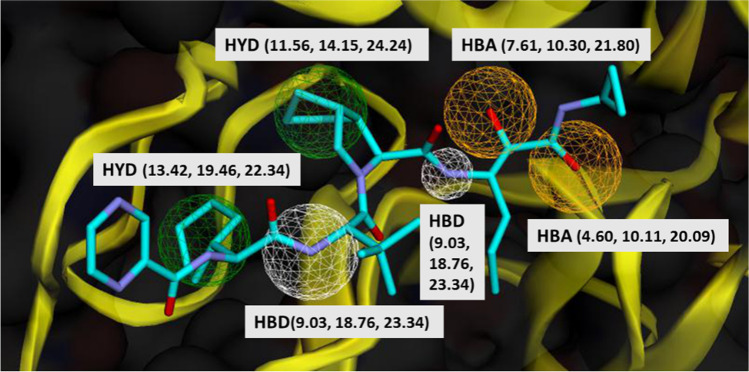

Twenty six active inhibitors of Mpro were collected, by advanced literature search and UniProt (https://www.uniprot.org/). These compounds were docked to the Mpro active site by using SwissDock. Binding energy ranged between − 6.9 kcal/mol (shikonin) to − 10.26 kcal/mol (ritonavir) (Fig. 3). Crystal structure of Mpro in complex with active inhibitors and the corresponding binding energies has been provided in Fig. S1. To develop pharmacophores, the Mpro-telaprevir complex was analyzed in Pharmit. Twenty pharmacophoric features were recognized at the first step. In the next step, 10 pharmacophore models were made with 4 to 6 features in each model. To select the best model, actives and decoys libraries were screened by these models. Among the 10 pharmacophore models, the model with the best score (Pharm_A) was used for screening the “ZINC natural products.” The characteristics of Pharm_A including x, y, z coordinates are illustrated in Fig. 4. Five of the six hydrogen bonds and one of the four hydrophobic interactions between Mpro and telaprevir were used in Pharm_A development. These non-bond interactions can be listed as follows: one hydrogen bond between N39 and Arg74, N32 and Gly34, O31 and Ser76; two hydrogen bonds between N22 and Asp38, Gly227; and one hydrophobic interaction between C28, C29 and Leu223, Ile304.

Fig. 3.

List of 27 known active inhibitors of Mpro and their binding energy towards Mpro obtained by molecular docking method. The number in parenthesis shows the estimated binding energy (kcal/mol)

Fig. 4.

The structure of Pharm_A. HBA. hydrogen acceptor; HBD, hydrogen donor; HYD, hydrophobic. Protein (Mpro) is depicted as yellow ribbon. Molecule description: blue, carbon; purple, nitrogen; red, oxygen. Numbers in parentheses show x, y, z coordinates of the pharmacophoric feature

Pharm_A model was used for virtual screening of the “ZINC natural products” databases by using ZINCPharmer. Based on Pharm_A features, 288 compounds were screened out from the “ZINC natural products.” Subsequently, the screened compounds were investigated using Lipinski’s rule of five, and 68 compounds exhibited satisfied drug-likeness properties according to this rule.

ADMET study

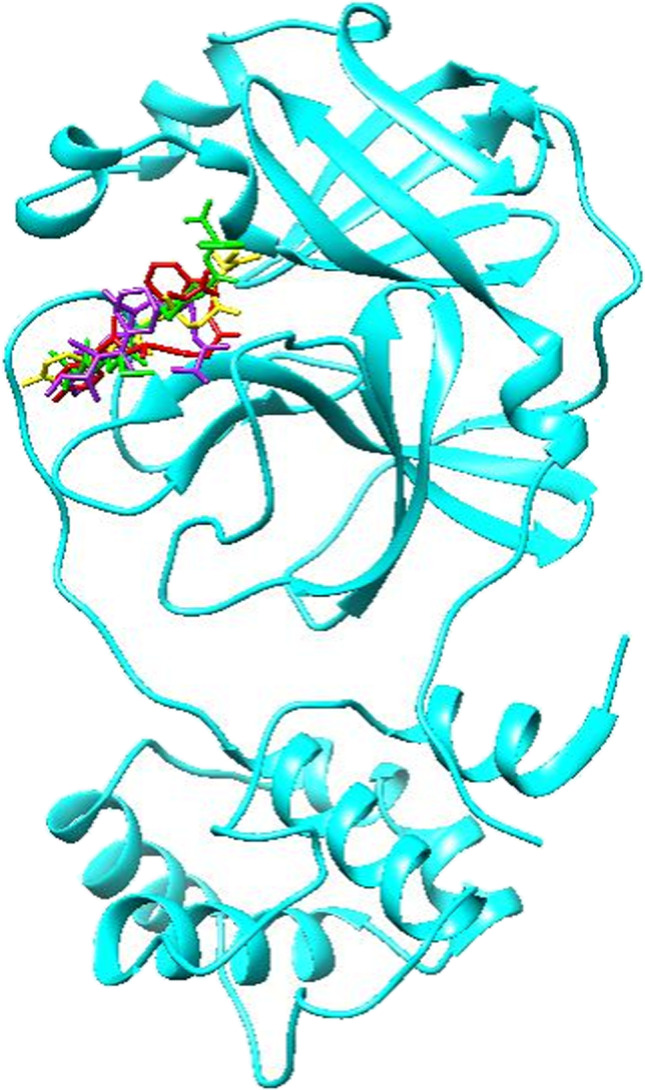

Besides specific binding to its target, a drug-like compound should have appropriate absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity, i.e., ADMET properties. Therefore, estimating ADMET properties of compounds is of great importance in the process of drug discovery. In this study, multiple ADMET properties were estimated and analyzed using SwissADME and ProTox-II webserver. By using SwissADME, the key physicochemical descriptors, ADME parameters, pharmacokinetic, and drug-like properties were investigated. Moreover, hepatotoxicity, carcinogenicity, mutagenicity, and cytotoxicity were investigated by using ProTox-II. In this step, 15 compounds with better results were selected for more investigation (Fig. 5). Molecular properties and ADME results for the 4 selected compounds after the docking study can be found in Tables 1 and 2. The toxicity prediction of these compounds is presented in Table 3.

Fig. 5.

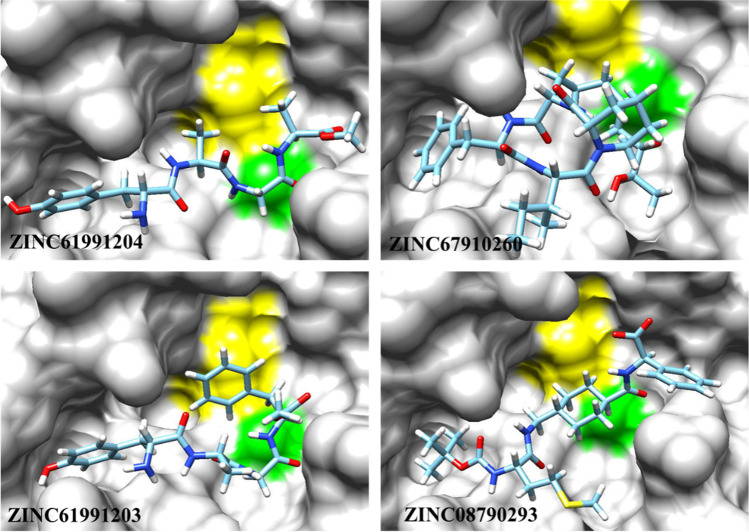

Compounds with the best binding energies including ZINC61991204 (yellow), ZINC67910260 (purple), ZINC61991203 (red), and ZINC08790293 (green) in Mpro active site. Protein is depicted as cyan

Table 1.

Molecular properties of the selected compounds

| Compound | Formula | iLogP | TPSA | nHeavyAtoms | MW | nHBAa | nHBDb | nRotb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZINC61991204 | C18H26N4O6 | 2.23 | 159.85 | 28 | 394.42 | 7 | 5 | 13 |

| ZINC67910260 | C31H48N4O6 | 2.95 | 148.07 | 41 | 572.74 | 6 | 5 | 11 |

| ZINC61991203 | C24H30N4O6 | 2.43 | 159.85 | 34 | 470.52 | 7 | 5 | 15 |

| ZINC08790293 | C26H38N3O6S | 3.60 | 161.96 | 36 | 520.66 | 6 | 3 | 16 |

aNumber of hydrogen bond acceptor

bNumber of hydrogen bond donor

Table 2.

ADME properties of the selected compounds predicted by SwissADME

| Compound | GIAa | BBBPb | CYP1A2 inhibitor | CYP2C19 inhibitor | CYP2C9 inhibitor | CYP2D6 inhibitor | CYP3A4 inhibitor | Lipinski | Log S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZINC61991204 | Low | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | − 3.20 |

| ZINC67910260 | Low | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | − 6.58 |

| ZINC61991203 | Low | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | − 5.66 |

| ZINC08790293 | Low | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | − 5.54 |

aGastrointestinal absorption

bBlood-brain barrier permanent

Table 3.

Toxicity risk of the selected compounds predicted by ProTox-II. The numbers in parentheses show probability

| Compound | Hepatotoxicity | Carcinogenicity | Mutagenicity | Cytotoxicity | Predicted LD50 | Predicted toxicity Classa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZINC61991204 | Inactive (0.92) | Inactive (0.72) | Inactive (0.77) | Inactive (0.65) | 5,300 mg/kg | 6 |

| ZINC67910260 | Inactive (0.77) | Inactive (0.65) | Inactive (0.78) | Inactive (0.79) | 2,287 mg.kg | 5 |

| ZINC61991203 | Inactive (0.88) | Inactive (0.72) | Inactive (0.76) | Inactive (0.66) | 5,300 mg/kg | 6 |

| ZINC08790293 | Inactive (0.89) | Inactive (0.62) | Inactive (0.73) | Inactive (0.63) | 1,000 mg/kg | 4 |

a “Predicted toxicity class” is a number from 1 to 6 that higher numbers indicate lower toxicity

Molecular docking study

For further analysis of the binding modes of the selected compounds in the active site of Mpro, molecular docking studies were done. At the first step, to validate the docking procedure, telaprevir was docked into the active site of Mpro. The top-ranked pose was compared with crystallographic pose, and the calculated RMSD was found to be 1.17 Å that indicates a good prediction of the ligand’s pose on the Mpro active site by SwissDock server. Moreover, comparative analysis of the non-bond interaction of docked and crystallographic poses indicated the accuracy of the docking procedure. After validation of the docking procedure, the 15 compounds with the best ADMET results were docked into the active site of Mpro one by one to analyze their orientation, interactions, and free binding energy. Only those compounds were selected that besides good docking score had the most number of non-bond interactions, especially hydrogen bonds in Mpro binding site. Accordingly, four compounds including ZINC61991204, ZINC67910260, ZINC61991203, and ZINC08790293 with ∆Gbind (kcal/mol) of − 8.23, − 9.11, − 8.38, and − 8.37 were selected (Fig. 5).

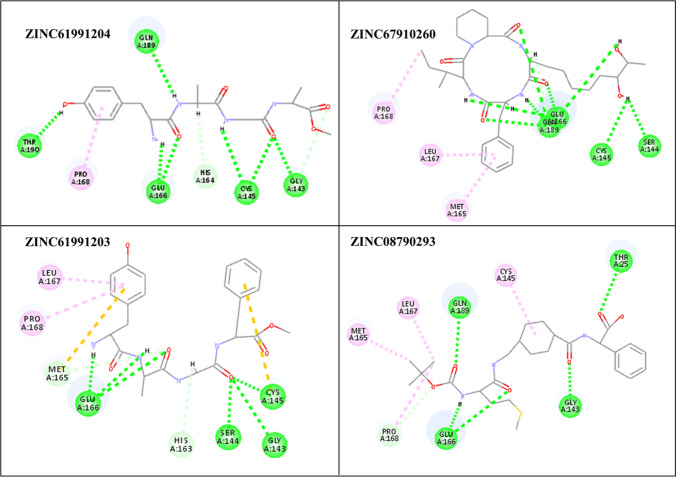

Orientation and non-bond interactions of the lead compounds in the active site of Mpro are depicted in Figs. 6, 7 and Table 4. In ZINC61991204, there are 7 hydrogen bonds including two hydrogen bonds between cys145 and N-H23 and C = O23, Glu166 and N-H21 and C = O25, hydrogen bond between Thr190 and O = H26, Gln189 and N-H24, Gly143:C = O23. There is also one hydrophobic interaction with Pro168. ZINC67910260 has ten hydrogen bonds including four hydrogen bonds between Glu166 and O-H44, C = O38, O-H46 and C-H15; four hydrogen bonds between Gln189 and C = O36, C = O37, O-H45 and C-H16; and one hydrogen bond between Ser144 and O-H28, Cys145 and O-H28. Met165, Leu167, Pro168 contribute to the Pi-Alkyl interactions. ZINC61991203 makes six hydrogen bonds with Mpro including three hydrogen bonds between C = O29 and Gly143, Ser144 and Cys145 and three hydrogen bonds between Glu166 and C = O30, N-H28 and N-H25. Leu167 and Pro168 contribute to Pi-Alkyl interaction; Met165, Cys145 contribute to Pi-Sulfur interaction. In ZINC08790293, there are five hydrogen bonds including one hydrogen bond between Thr25 and C = O23, Gly143 and C = O31, Glu146 and C = O32, Glu146 and N-H38, Gln189 and C = O34. Cys145, Leu167, Met165 contribute to the Pi-Alkyl interactions.

Fig. 6.

The best binding pose of the selected compounds in the active site of Mpro resulting from the docking studies. His41 and Cys145, residues of the catalytic dyad, are depicted as green and yellow, respectively

Fig. 7.

Non-bond interactions of the selected compounds in the active site of Mpro. Green, hydrogen bond; pink, amide-Pi stacked; light pink, Pi-alkyl; orange, Pi-sulfur

Table 4.

Non-bond interactions of the selected compounds and telaprevir in the active site of Mpro

| Compound | Hydrogen bonds | Pi-alkyl | Pi-sulfur |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZINC61991204 | Thr190:O = H26, Gln189:N-H24, Glu166:N-H21, Glu166:C = O25, Cys145:N-H23, Cys145:C = O23, Gly143:C = O26 | Pro168 | - |

| ZINC67910260 | Ser144:O-H28, Cys145:O-H28, Glu166:O-H44, Glu166:C = O38, Glu166:O-H46, Glu166:C-H15, Gln189:C = O36, Gln189:C = O37, Gln189:O-H45, Gln189:C-H16 | Met165, Leu167, Pro168 | - |

| ZINC61991203 | Gly143:C = O29, Ser144:C = O29, Cys145:C = O29, Glu166:C = O30, Glu166:N-H28, Glu166:N-H25 | Leu167, Pro168 | Met165, Cys145 |

| ZINC08790293 | Thr25:C = O23, Gly143:C = O31, Glu146:C = O32, Glu146:N-H38, Gln189:C = O34 | Cys145, Leu167, Met165 | - |

The analysis of the docking poses indicates that six residues have great impact in non-bond interactions and maintaining the conformation of the selected compounds in the active site of Mpro. These residues include Ser84, Gly227 and catalytic Asp38 and Asp225 that make hydrogen bonds with ligands and Leu223 and Ile304 that contribute to hydrophobic interactions. Five of these seven residues including Ser84, Gly38, Gly227, Leu223, and Ile304 contributed to Pharm_A features.

Molecular dynamic simulation study

Receptor-ligand interaction is a dynamic event and one of the best ways to grasp the stability and flexibility of a receptor-ligand complex and binding energy of ligand to receptor and is analyzing the behavior and motion of the complex in a simulated environment very similar to a natural environment that includes water and ions [45]. Herein, the complexes docking file of selected four natural compounds including ZINC61991204, ZINC67910260, ZINC61991203, and ZINC08790293 and one reference ligand bind with Mpro were simulated in an explicit hydration environment to evaluate the stability, flexibility, and intermolecular interactions between protein and compounds during the simulation time. Therefore a short, 10 ns simulation was performed for all the complexes, and it was observed that ZINC61991203 and ZINC08790293 were unstable in the active site of Mpro and began to dissociate from the active site after about 7 ns of simulation. However, ZINC61991204 and ZINC67910260 were stable in the active site. So these two compounds were selected for further analysis. In this step, molecular dynamic simulation was performed on Mpro for 50 ns, and 3 different conformations from the trajectory were used to re-dock ZINC61991204, ZINC67910260, and telaprevir to the binding site of Mpro (Fig. S2). Then, a 100 ns molecular dynamic simulation was performed on all complexes resulting from docking to prove their stable binding to Mpro. In the next steps, simulation trajectory of these compounds was further analyzed by several tools.

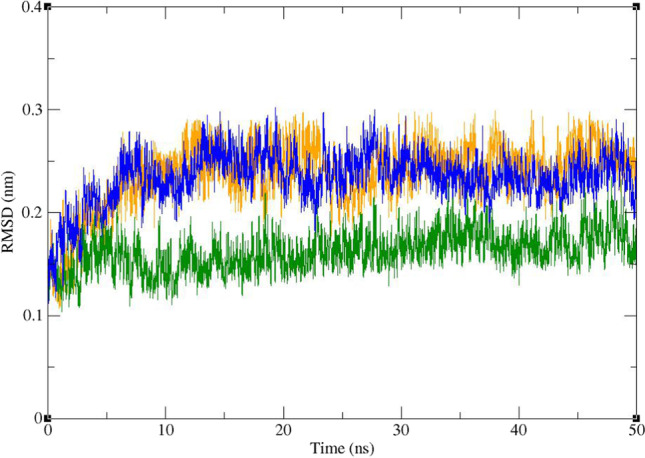

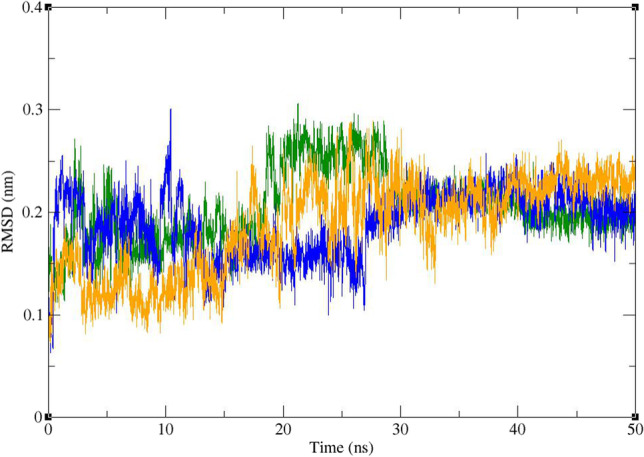

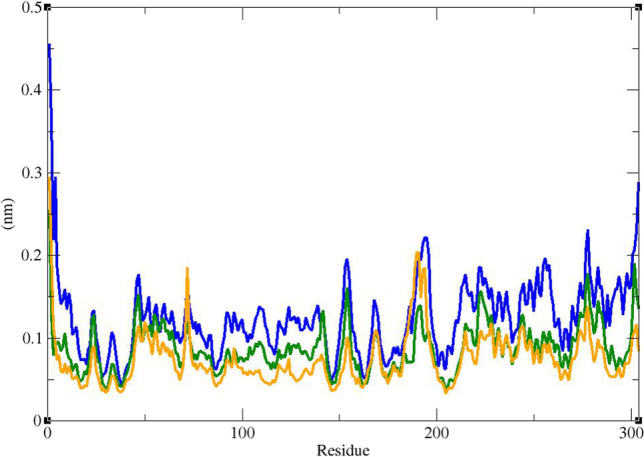

RMSD and radius of gyration (Rg) were calculated for all the saved structures during the MD simulation, and changes in the amount of these factors during the simulation time were used for evaluation of the stability of the complexes. RMSF of the backbone atoms was also calculated for assessment of residual flexibility during the time of simulation. The results of these calculations are shown in Figs. 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12. As it could be seen in Fig. 8, the RMSD value of Mpro gets stable after 10 ns of simulation and remains stable and less than 3 Å for the rest of simulation time. The average RMSD value of Mpro in complex of Mpro with ZINC61991204, ZINC67910260, and telaprevir was 0.163 Å, 0.234 Å, and 0.239 Å, respectively. RMSD of lead compounds and telaprevir in complex with Mpro was less than 3 Å during the simulation time; however, it became stable only after 30 ns (Fig. 9). The average RMSD value of ZINC61991204, ZINC67910260, and telaprevir in complexes with Mpro was 0.199 Å, 0.209 Å, and 0.210 Å, respectively. All these results indicate the stability of the ligands in the active site of Mpro especially during the last 20 ns of simulation.

Fig. 8.

Superimposed RMSD of the Cα atoms of Mpro in complex with ZINC61991204 (green), ZINC67910260 (orange), and telaprevir (blue)

Fig. 9.

Superimposed RMSD of ZINC61991204 (green), ZINC67910260 (orange), and telaprevir (blue) in complex with Mpro

Fig. 10.

RMSF graph of the Cα atoms of Mpro in complex with ZINC61991204 (green), ZINC67910260 (orange), and telaprevir (blue)

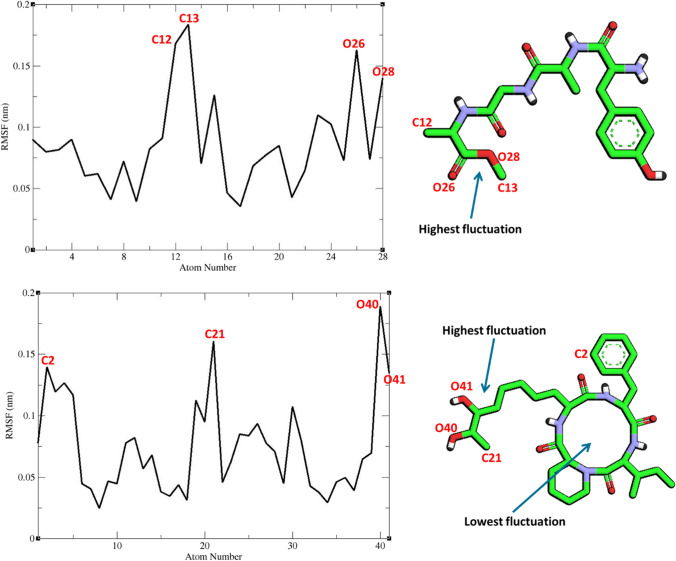

Fig. 11.

RMSF graph of the heavy atoms of ZINC61991204 and ZINC67910260 in complex with Mpro. Structure of these compounds and parts of these molecules with highest and lowest fluctuations are illustrated

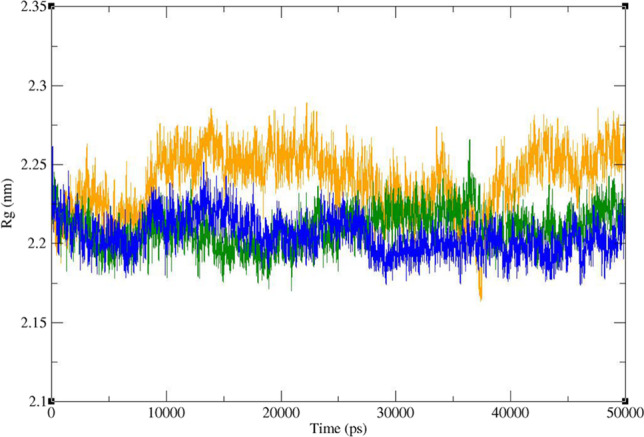

Fig. 12.

Time dependence of the radius of gyration (Rg) graph of Mpro in complex with ZINC61991204 (green), ZINC67910260 (orange), and telaprevir (blue)

Figure 10 shows that RMSF of the Cα atoms of Mpro in complexes with ZINC61991204, ZINC67910260, and telaprevir was very similar. As it could be seen, Mpro is not a very flexible protein. In all complexes, except the first two residues in Mpro-telaprevir complex, residues had low RMSF values of less than 0.3 Å. In fact, residues involved in non-bond interactions with ligands had little fluctuation like other residues during the simulation time. The little fluctuation of these residues could demonstrate their capability in making stable non-bond interaction with lead compounds and telaprevir. RMSF of heavy atoms of ligands were calculated (Fig. 11). All atoms had a very low RMSF value of less than 2 Å. In ZINC67910260, the least fluctuation was related to a ring consisting of 12 heavy atoms including 4 repeats of N–H, C = O, C. Therefore, in this ring, hydrogen bond donor, i.e., N–H, and hydrogen bond acceptor, i.e., C = O, are repeated 4 times. Being in a ring led to lower fluctuation and subsequently to more stable hydrogen bonds of N–H and C = O with enzyme. On the other hand, more stable hydrogen bonds contribute to lower fluctuation of the ring’s atoms. In fact, this part of the ligand had the most number of hydrogen bonds with Mpro. In ZINC61991204, parts of the ligand involved in hydrogen bond with Mpro had the lowest fluctuation. Highest fluctuation was related to part of the ligand that had only one carbon hydrogen bond with the enzyme.

Radius of gyration (Rg) of Mpro was calculated to evaluate the compactness of protein during the period of simulation (Fig. 12). Rg value of Mpro in complex with the lead compounds as well as telaprevir remained between narrow ranges of 2.175 to 2.285 nm and did not show a significant upward or downward trend during the simulation time. The average Rg of Mpro was 2.209, 2.244, and 2.204 in the complex of Mpro with ZINC61991204, ZINC67910260, and telaprevir, respectively.

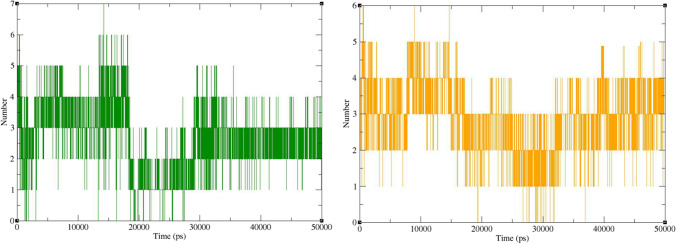

The number of hydrogen bonds between ligands and Mpro during the MD simulation was calculated by analyzing the MD trajectories (Fig. 13). Accordingly, the number of hydrogen bonds changes mostly between 2 and 4 for both complexes. These numbers are less than the number of hydrogen bonds predicted by docking studies (Fig. 7). This is not unexpected in dynamic simulation studies as the conformation of both ligand and the receptor fluctuates during the simulation time, and therefore, a wide variety of interactions arise [46]. However, binding energy analysis in the next step demonstrated that the overall impact of these interactions was in favor of ligand binding to the receptor.

Fig. 13.

Numbers of hydrogen bonds formed between Mpro and ZINC61991204 (green) and ZINC67910260 (orange)

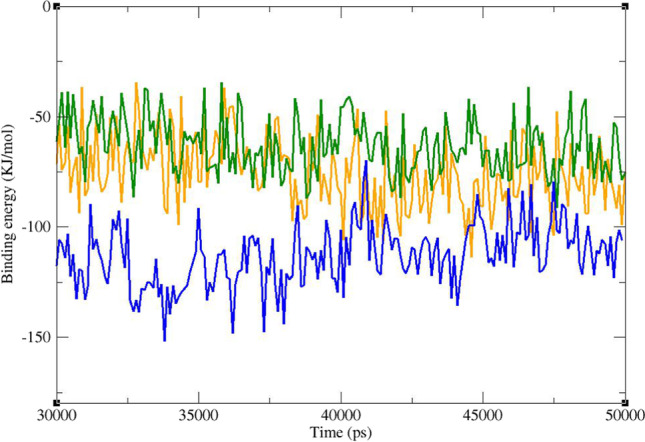

Binding free energy analysis

The MM/PBSA is a commonly used method for estimating binding energy of ligands to a protein receptor. It can reveal the nature of the dominant interactions in a ligand-receptor complex. In molecular docking, there is only a single snapshot of a structure, and therefore, binding free analysis may not be very accurate. But by simulation of molecular dynamics in a period of time and getting several snapshots of the ligand–protein complex, the binding energy estimation would be much more accurate. The result of free binding energy analysis is presented in Table 5. In this study, the lead compounds and telaprevir revealed average negative binding energies. The average MM/PBSA free binding energy of the known co-crystal inhibitor (telaprevir) with Mpro was − 109.49 kJ/mol, while ZINC61991204 and ZINC67910260 exhibited − -79.32 and − 77.96 kJ/mol binding free energies, respectively. Diagram of binding energy changes during the last 20 ns of simulation time is presented in Fig. 14. In all these complexes, binding energy fluctuates in a narrow negative range, and the complex is stable during all the simulation time. ZINC61991204 and ZINC67910260 had lower binding energies regarding the co-crystal inhibitor, i.e., telaprevir; however, they were completely stable in the active site of Mpro. In fact, binding energy of − 79.32 and − 77.96 kJ/mol was sufficient for making a stable complex between a small molecule like ZINC61991204 or ZINC67910260 and Mpro active site. Free energy components of the complexes were further inspected for evaluating types of energy in making complexes by the g_mmpbsa method. It was revealed that molecular mechanics interaction energy was favorable and solvation energy (the sum of polar solvation energy and SASA energy) was unfavorable regarding formation of Mpro-ligand complex. In fact van der Waals and electrostatic energies were negative, and solvation energy was positive in all Mpro-ligand complexes. The value of van der Waals energy was higher than that of the electrostatic energy.

Table 5.

Binding free energy (KJ/mol) for two selected compounds and telaprevir

| Complex | van der Waals energy | Electrostatic energy | Polar solvation energy | SASA a energy | Binding energy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZINC61991204 | − 151.62 | − 52.31 | 160.87 | − 19.03 | − 62.09 | |||

| ZINC67910260 | − 184.76 | − 56.45 | 189.52 | − 22.90 | − 74.59 | |||

| Telaprevir | − 212.35 | − 14.69 | 138.60 | − 24.78 | − 113.22 | |||

aSolvent accessible surface area

Fig. 14.

Diagram of binding energy changes during the last 20 ns of simulation time. Mpro in complex with ZINC61991204 (green), ZINC67910260 (orange), and telaprevir (blue)

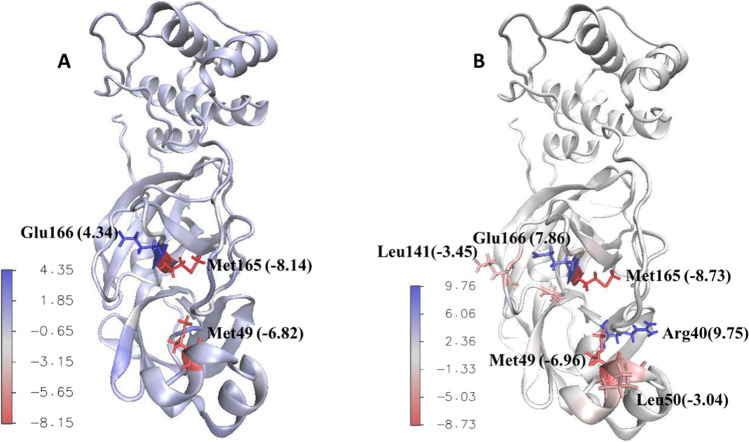

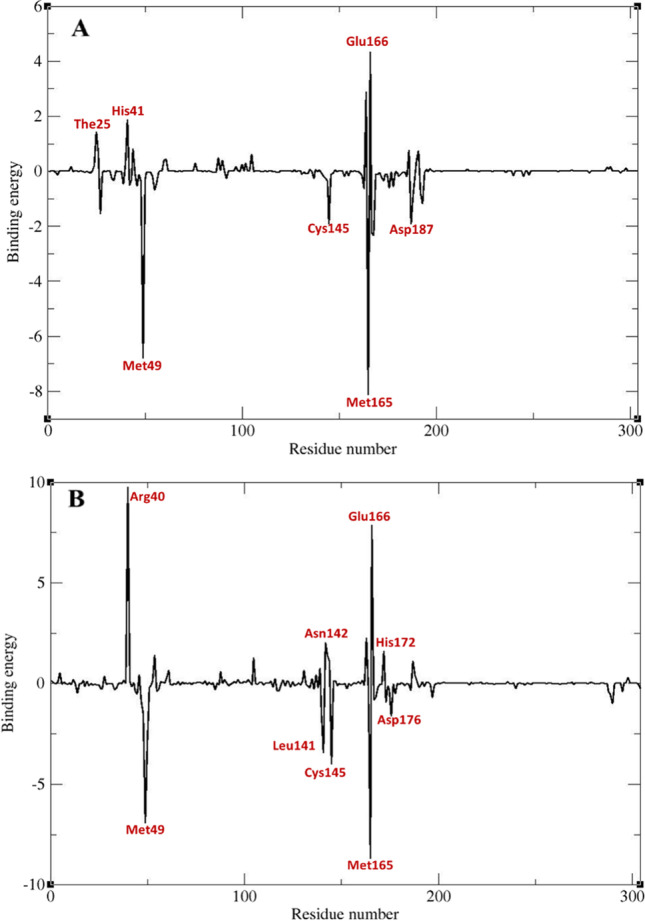

By g_mmpbsa contribution of all residues of the protein to the binding energy was calculated. Most of the residues that were found to be important in ligand-receptor interaction based on docking studies had negative values in dynamic simulation study too, while a few of these residues showed little or almost no contribution. Beside these residues, some new residues were found to have a high contribution to the binding energy. Because of dynamic behavior of macromolecules and their ligands, it is quite expected to see new intermolecular interactions between receptor and ligand during dynamic simulations studies that were not noticed in docking studies. Accordingly in this study, new residues were found in dynamic simulation study that based on docking studies, their role in ligand-receptor interaction was not identified. Four residues including His41, Met49, Cys145, and Glu166 had large contribution to the binding energy in all complexes. In Mpro-ZINC61991204 complex, The25, His41, and Glu166 had the most negative contribution, and Met49, Cys145, Met165, and Asp187 had the most positive effect to the binding energy. In Mpro-ZINC67910260 complex, Arg40, Asn142, Glu166, and His172 had the most negative contribution, and Met49, Leu141, Cys145, Met165, and Asp176 had the most positive effect to the binding energy (Figs. 15 and 16).

Fig. 15.

Contribution of Mpro residues to the binding energy (KJ/mol). Mpro-ZINC61991204 complex (A) and Mpro-ZINC67910260 complex (B)

Fig. 16.

Residues with the largest and smallest contribution to the binding energy (KJ/mol) of Mpro-ZINC61991204 complex (A) and Mpro- ZINC67910260 complex (B)

Conclusion

Mpro-telaprevir complex was used for developing a structure-based pharmacophore model by using pharmit. “ZINC Natural Products” was screened, and 288 compounds were filtered according to pharmacophore features. After applying Lipinski’s rule of five, this number reduced to 68. In the next step, physicochemical descriptors were computed to predict ADME parameters, and then the selected compounds were screened according to their predicted toxicity which resulted in 15 compounds. These compounds were docked to the active site of Mpro, and those with the highest binding scores and better interaction were selected. Accordingly ZINC61991204, ZINC67910260, ZINC61991203, and ZINC08790293 were selected for further analysis to evaluate their dynamic behavior in complex with Mpro. The result of dynamic studies showed that ZINC61991203 and ZINC08790293 dissociated from Mpro active site after 7 ns; however, ZINC426421106 and ZINC5481346 were stable. So the simulation time was extended for another 90 ns to better understand the behavior of these compounds in the active site of Mpro. These compounds were stable in extended simulation time too. In the next steps, RMSD, RMSF, Rg, and number of hydrogen bonds were calculated, and MM/PBSA analysis was done. The result of all the analysis indicated that ZINC61991204 and ZINC67910260 are drug-like and nontoxic and have a high potential for inhibiting Mpro. In our ongoing investigation, we are going to experimentally evaluate Mpro inhibitory activity of these two proposed compounds hoping these compounds could serve as appropriate hit molecules for the development of Mpro inhibitors as anti-SARS-CoV-2 agents.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contribution

M. Halimi optimized the entire study and wrote the manuscript. P. Bararpour collected the initial data set and helped in docking and interaction analyses. The final manuscript was read and approved by all authors.

Funding

This work was funded through a grant provided by Babol Branch, Islamic Azad University.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Tisdell CA. Economic, social and political issues raised by the COVID-19 pandemic. Econ Anal Policy. 2020;68:17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.eap.2020.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanne JH. Covid-19: Mental health and economic problems are worse in US than in other rich nations. BMJ. 2020;370:m3110. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Codagnone C, et al. Assessing concerns for the economic consequence of the COVID-19 response and mental health problems associated with economic vulnerability and negative economic shock in Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(10):e0240876. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zheng C, et al. Real-world effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines: a literature review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;114:252–260. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh JA, Upshur REG. The granting of emergency use designation to COVID-19 candidate vaccines: implications for COVID-19 vaccine trials. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(4):e103–e109. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30923-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Samaranayake LP, Seneviratne CJ, Fakhruddin KS (2021) Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines: a concise review. Oral Dis 00:1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Shi K, et al. Severe type of COVID-19: pathogenesis, warning indicators and treatment. Chin J Integr Med. 2022;28(1):3–11. doi: 10.1007/s11655-021-3313-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng Q, et al. Efficacy and safety of current treatment interventions for patients with severe COVID-19 infection: a network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Med Virol. 2021;94(4):1617–1626. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Odeti S, Yellepeddi VK. Remdesivir (Veklury) for the treatment of COVID-19 in hospitalized patients. Am Fam Physician. 2021;104(3):311–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mozaffari E, et al. Remdesivir treatment in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a comparative analysis of in-hospital all-cause mortality in a large multi-center observational cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;75(1):e450–e458. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.No authors listed (2022) COVID-19 update: baricitinib (Olumiant) FDA-approved for treatment of COVID-19. Med Lett Drugs Ther 64(1652):e2–e3 [PubMed]

- 12.Tanne JH. Covid-19: FDA authorises pharmacists to prescribe Paxlovid. BMJ. 2022;378:o1695. doi: 10.1136/bmj.o1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perez-Alba E, et al. Baricitinib plus dexamethasone compared to dexamethasone for the treatment of severe COVID-19 pneumonia: a retrospective analysis. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2021;54(5):787–793. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2021.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.No authors listed (2022) Paxlovid for treatment of COVID-19. Med Lett Drugs Ther 64(1642):9–10 [PubMed]

- 15.Mahase E. Covid-19: Pfizer’s paxlovid is 89% effective in patients at risk of serious illness, company reports. BMJ. 2021;375:n2713. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n2713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma A, Gupta SP (2017) Fundamentals of viruses and their proteases. Viral Proteases Their Inhib 1–24

- 17.Agbowuro AA, et al. Proteases and protease inhibitors in infectious diseases. Med Res Rev. 2018;38(4):1295–1331. doi: 10.1002/med.21475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Razali R, Asis H, Budiman C. Structure-function characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 proteases and their potential inhibitors from microbial sources. Microorganisms. 2021;9(12):2481. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9122481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang L, et al. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease provides a basis for design of improved a-ketoamide inhibitors. Science. 2020;368:4. doi: 10.1126/science.abb3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jin Z, et al. Structure of M(pro) from SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of its inhibitors. Nature. 2020;582(7811):289–293. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2223-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klein F, et al. Two-year follow-up analysis of telaprevir-based antiviral triple therapy for HCV recurrence in genotype 1 infected liver graft recipients as a first step towards modern HCV therapy. Hepat Res Treat. 2016;2016:8325467. doi: 10.1155/2016/8325467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobson IM, et al. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(25):2405–2416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1012912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gentile I, et al. Telaprevir: a promising protease inhibitor for the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16(9):1115–1121. doi: 10.2174/092986709787581789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kneller DW, et al. Malleability of the SARS-CoV-2 3CL M(pro) active-site cavity facilitates binding of clinical antivirals. Structure. 2020;28(12):1313–1320 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2020.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kneller DW, et al. Direct observation of protonation state modulation in SARS-CoV-2 main protease upon inhibitor binding with neutron crystallography. J Med Chem. 2021;64(8):4991–5000. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qiao J, et al. SARS-CoV-2 M(pro) inhibitors with antiviral activity in a transgenic mouse model. Science. 2021;371(6536):1374–1378. doi: 10.1126/science.abf1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oerlemans R, et al. Repurposing the HCV NS3-4A protease drug boceprevir as COVID-19 therapeutics. RSC Med Chem. 2020;12(3):370–379. doi: 10.1039/D0MD00367K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stan D, et al. Natural compounds with antimicrobial and antiviral effect and nanocarriers used for their transportation. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:723233. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.723233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wijayasinghe YS, et al. Natural products: a rich source of antiviral drug lead candidates for the management of COVID-19. Curr Pharm Des. 2021;27(33):3526–3550. doi: 10.2174/1381612826666201118111151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sunseri J, Koes DR. Pharmit: interactive exploration of chemical space. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):W442–W448. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vuorinen A, Schuster D. Methods for generating and applying pharmacophore models as virtual screening filters and for bioactivity profiling. Methods. 2015;71:113–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2014.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grosdidier A, Zoete V, Michielin O (2011) SwissDock, a protein-small molecule docking web service based on EADock DSS. Nucleic Acids Res 39(Web Server issue): W270–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Grosdidier A, Zoete V, Michielin O. Fast docking using the CHARMM force field with EADock DSS. J Comput Chem. 2011;32(10):2149–2159. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mysinger MM, et al. Directory of useful decoys, enhanced (DUD-E): better ligands and decoys for better benchmarking. J Med Chem. 2012;55(14):6582–6594. doi: 10.1021/jm300687e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Braga RC, Andrade CH. Assessing the performance of 3D pharmacophore models in virtual screening: how good are they? Curr Top Med Chem. 2013;13(9):1127–1138. doi: 10.2174/1568026611313090010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu SH, et al. The discovery of potential acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: a combination of pharmacophore modeling, virtual screening, and molecular docking studies. J Biomed Sci. 2011;18:8. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-18-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Daina A, Michielin O, Zoete V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42717. doi: 10.1038/srep42717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lipinski CA, et al. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1997;23(1–3):3–25. doi: 10.1016/S0169-409X(96)00423-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferreira LLG, Andricopulo AD. ADMET modeling approaches in drug discovery. Drug Discov Today. 2019;24(5):1157–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2019.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Banerjee P, et al. ProTox-II: a webserver for the prediction of toxicity of chemicals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(W1):W257–W263. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hanwell MD, et al. Avogadro: an advanced semantic chemical editor, visualization, and analysis platform. J Cheminform. 2012;4(1):17. doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-4-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pettersen EF, et al. UCSF Chimera–a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25(13):1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abraham MJ, et al. GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX. 2015;1–2:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.softx.2015.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zoete V, et al. SwissParam: a fast force field generation tool for small organic molecules. J Comput Chem. 2011;32(11):2359–2368. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karplus M, McCammon JA. Molecular dynamics simulations of biomolecules. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9(9):646–652. doi: 10.1038/nsb0902-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Naqvi AAT, et al. Advancements in docking and molecular dynamics simulations towards ligand-receptor interactions and structure-function relationships. Curr Top Med Chem. 2018;18(20):1755–1768. doi: 10.2174/1568026618666181025114157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Not applicable.