Abstract

The oral microbiome, like the fecal microbiome, may be related to breast cancer risk. Therefore, we investigated whether the oral microbiome was associated with breast cancer and non-malignant breast disease, and its relationship with the fecal microbiome in a case-control study in Ghana. A total of 881 women were included (369 breast cancers, 93 non-malignant cases, and 419 population-based controls). The V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was sequenced from oral and fecal samples. Alpha-diversity (observed amplicon sequence variants [ASVs], Shannon index, and Faith’s Phylogenetic Diversity) and beta-diversity (Bray-Curtis, Jaccard, and weighted and unweighted UniFrac) metrics were computed. MiRKAT and logistic regression models were used to investigate the case-control associations. Oral sample alpha-diversity was inversely associated with breast cancer and non-malignant breast disease with odds ratios (95% CIs) per every 10 observed ASVs of 0.86 (0.83–0.89) and 0.79 (0.73–0.85), respectively, compared with controls. Beta-diversity was also associated with breast cancer and non-malignant breast disease compared with controls (P≤0.001). The relative abundances of Porphyromonas and Fusobacterium were lower for breast cancer cases compared with controls. Alpha-diversity and presence/relative abundance of specific genera from the oral and fecal microbiome were strongly correlated among breast cancer cases, but weakly correlated among controls. Particularly, the relative abundance of oral Porphyromonas was strongly, inversely correlated with fecal Bacteroides among breast cancer cases (r=−0.37, P≤0.001). Many oral microbial metrics were strongly associated with breast cancer and non-malignant breast disease, and strongly correlated with fecal microbiome among breast cancer cases, but not controls.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Ghana, Non-malignant breast diseases, Oral microbiome, Fecal microbiome

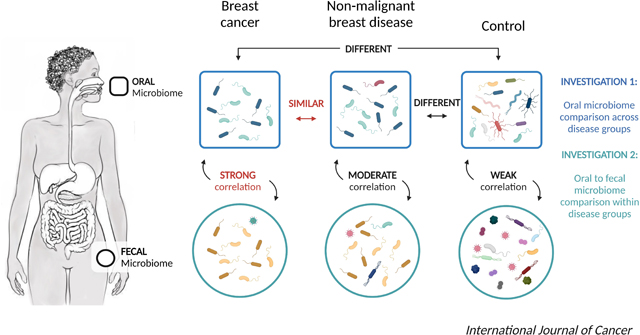

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of cancer death among women worldwide, with an estimated 2,088,849 new cases and 626,679 deaths occurring in 2018.[1] Breast cancer incidence and mortality is rising in Africa[1] with the highest breast cancer mortality rates compared to the rest of the world.[2, 3] The burden of breast cancer in sub-Saharan Africa is projected to double between 2012 and 2030 due to population aging and expansion.[4] Although several genetic-epigenetic determinants and environmental risk factors for breast cancer have been described, understanding of the underlying mechanisms for breast cancer is still not fully characterized.

In recent years, numerous studies have characterized the microbiome of different health conditions and observed complex interactions between the microbiome and host.[5–7] Specifically, there are indications of a link between the oral microbiome and breast cancer. Some studies have observed an higher risk of breast cancer among women with periodontal disease,[8, 9] a condition caused by specific bacteria, such as the red complex (Porphyromonas gingivalis, Tannerella forsythia, Treponema denticola) and the orange complex (Fusobacterium nucleatum, Prevotella intermedia, Prevotella nigrescens, Peptostreptococcus micros, Streptococcus constellatus, Eubacterium nodatum, Campylobacter showae, Campylobacter gracilis, and Campylobacter rectus).[10, 11] However, studies of periodontal disease provide only indirect evidence that the oral microbiome may be involved and studies considering the relationship between the oral microbiome and breast cancer are currently limited. Only one small study has been conducted with 55 breast cancer cases and 21 non-cancer patients in the United States which reported no associations between the oral microbiome and breast cancer.[12] Therefore, larger studies and studies in different populations are needed.

The Ghana Breast Health Study is a population-based case-control study conducted in Accra and Kumasi, Ghana, West Africa. In the fecal microbiome analysis in this population, breast cancer and non-malignant breast disease cases had similar fecal microbial characteristics but were significantly different from controls. Fecal alpha-diversity was inversely associated with breast cancer and non-malignant breast disease, and associations were observed for beta-diversity and multiple taxa.[13] To further explore the potential role of human microbiome in breast cancer development, we investigated the associations of the oral microbiome with breast cancer and non-malignant breast disease in the Ghana Breast Health Study; and the relationship of the oral microbiome with the fecal microbiome.

Materials and Methods

Study population selection

The Ghana Breast Health Study is a population-based case-control study of breast cancer in the Accra and Kumasi areas in Ghana, which has been described in detail previously.[14] In brief, 2,218 breast cancer cases or non-malignant breast disease cases and 2,352 population controls were recruited. The study cases were identified from three hospitals: Korle Bu Teaching Hospital in Accra and Komfo Anoyke Teaching Hospital and Peace and Love Hospital in Kumasi. Eligibility criteria for study cases included being 18–74 years of age and have lived in study areas for at least a year’s time, being potential cases recommended for a biopsy given lesions suspicious for malignancy or presenting at a study hospital for treatment of pathologically documented breast cancer diagnosed within the preceding year. Because many women present with advanced breast cancers, the Ghana Breast Health Study focused on enrolling potential cases at the time of their biopsies prior to a pathologic diagnosis, so only a small proportion of cancer cases were women presenting at the hospital for treatment.[14] Diagnoses were based on pathologic review of core biopsies by pathologists in Ghana and the National Cancer Institute (NCI). Population controls were identified using a household census of randomly selected enumeration areas that gave rise to the cases, had at least 1 year of residence in the study areas, and were frequency matched to cases by age.

Previously, all 415 breast cancer cases with more than one stool sample available, 110 city frequency-matched non-malignant breast disease cases, and 447 city frequency-matched controls were selected to study the associations of fecal microbiome with breast cancer and non-malignant breast disease.[13] For this oral microbiome study, women who were included in the fecal study and had an available saliva sample were selected, including 392 breast cancer cases, 100 non-malignant breast disease cases, and 433 controls. Five women who were diagnosed with a cancer other than breast cancer were excluded. For the oral microbiome only analysis, after excluding 39 samples with less than 20,000 reads (19 cancers, 7 non-malignant cases, and 13 controls), the final sample size was 881 women. For the combined oral and fecal microbiome analysis, 80 subjects with less than 6,250 reads from either oral or fecal samples were excluded (34 cancers, 11 non-malignant cases, and 35 controls), and the final sample size was 840 women.

Questionnaire data and sample collection

The demographic and lifestyle data for the study were collected via a standardized interview-based questionnaire, which focused on demographic characteristics and breast cancer risk factors. The original questionnaire response rates were 99.2% for breast cancer and non-malignant breast disease cases and 91.9% for eligible controls.[14] Body size measurements, including height (cm) and weight (kg), were taken by study personnel and recorded.

Saliva samples were collected using Oragene DNA OGR-500 kits (DNA Genotek Inc., Ottawa, Canada) at the initial clinic study visit for both cases and controls. Saliva samples were collected prior to neoadjuvant therapy. Saliva samples were collected, stored, and shipped to the NCI repository at room temperature annually, and were then transferred from the NCI repository to the Cancer Genomics Research Laboratory on dry ice. Stool sample collection procedures were described in detail previously.[13] Briefly, two vials of stool samples from a subset of cases and controls were collected at the initial clinic study visit, if possible. If controls were unable to provide stool samples at the study visit, they took the collection materials home and, after collection, the samples were transported immediately to the laboratory by study personnel. The impact of microbial differences for fecal samples collected in the hospital compared to at home was evaluated in the previous fecal microbiome study and minimal effects were detected.[13] Upon receipt in the laboratory, one vial of the stool sample was snap frozen at −80° C and 2.5 mL of RNAlater stabilizing solution (Ambion, Inc., Austin, Texas) was added to the other vial and frozen at −80° C. The fecal samples were shipped to the NCI repository on liquid nitrogen every 3–4 months.

DNA extraction and sequencing

Saliva samples were processed at the Cancer Genomics Research Laboratory. The saliva samples were thawed at 4°C and 850 μL of material was transferred into a new tube and pelleted. After removing the supernatant, 5 mL of Buffer P1 (Qiagen) was added to each tube and thoroughly mixed before pelleting again. After removing the supernatant, 20 μL of Proteinase K and 980 μL of Buffer G2 (Qiagen) were added to each tube and thoroughly mixed. Samples were then incubated in a water bath for 60 minutes at 56°C. Immediately following off-board lysis, DNA was extracted using the DSP DNA Virus Pathogen Kit (Qiagen) on a QIAsymphony automated extraction instrument (Qiagen) using a customized version of the Complex800_V6_DSP protocol. DNA of the quality control (QC) samples were extracted separately, and PCR amplification and sequencing of all extracted DNA were completed, as described in detail previously.[15] Within each PCR batch, eight QC samples were also included: two oral artificial communities, [16] two water blanks, two robogut samples,[16] and two duplicates of randomly selected control samples. PCR batches were created by randomly selecting study participants to have an adequate distribution of both cases and controls within each batch. The V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was PCR amplified for 25 cycles and 2×250 bp paired end sequencing was performed on the Illumina MiSeq.

The methods for DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and sequencing of the fecal samples were described in detail previously.[13] In brief, fecal samples were sent to the Knight Laboratory (University of California, San Diego) on dry ice. DNA extraction using the MO-BIO PowerMag Soil DNA Isolation Kit and the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was sequenced with paired-end 2×150 bp cycle chemistry on the Illumina MiSeq using Earth Microbiome Project (EMP) standard protocols (http://www.earthmicrobiome.org/protocols-and-standards/16s).

Bioinformatics

For the oral sample only analysis, sequence data were demultiplexed and minimally quality filtered using QIIME2 version 2019.1.[17] After running the DADA2 plugin using the parameter min-fold-parent-over-abundance 2.0, 5,358 amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) were generated. Eighty eight out of 5,358 ASVs were non-bacterial ASVs and were removed. Taxonomy was assigned to the resulting ASVs using SILVA classifier version v132.[18] The taxonomy data was filtered to only include bacterial sequences. Only 88 out of the 5,358 unique ASVs were non-bacterial ASVs. The median coverage reads/sample was 37,594, with a minimum coverage of 320 reads/sample and a maximum of 154,614 reads/sample. More than 97% of samples had more than 10,000 reads per sample. Based on rarefaction curves for alpha-diversity (Figure S1), we rarefied each oral sample to 20,000 sequences. Alpha-diversity measures (i.e., Observed ASVs, Faith’s Phylogenetic Diversity [PD], and Shannon Index) and beta-diversity measures (i.e., Bray-Curtis, Jaccard, weighted Unifrac, and unweighted Unifrac) were calculated based on the QIIME2 version 2019.1. Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) was calculated from the four beta-diversity distance matrices. For the oral and fecal sample analysis, original paired end RAW files from both the oral and fecal samples were combined. The same pipeline as described herein was run based on combined input data set. Due to the differing read depths and to be consistent with the fecal microbiome analysis,[13] we rarefied both the oral and fecal sample data to 6,250 sequences.

Quality control

The average inter-batch coefficients of variation (CV) of alpha-diversity for the included artificial community samples were 12.6%, 9.2%, and 1.6% for observed ASVs, Faith’s PD, and Shannon index, respectively, and for the robogut samples were 8.9%, 14.1%, and 1.0% for observed ASVs, Faith’s PD, and Shannon index, respectively. The intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) for the 22 PCR duplicates of randomly selected control samples were 0.97, 0.96, and 0.997 for observed ASVs, Faith’s PD, and Shannon Index, respectively. The artificial community, robogut, and study samples appeared to cluster separately based on visual inspection of the PCoA plots of the four beta-diversity measures (Figure S2). In the 22 blanks, the median number of reads was 7.5 reads/sample; only one blank sample had 2,077 reads.

Statistical analysis

Characteristics of study participants were summarized by breast cancer, non-malignant breast disease, and control status. For the oral microbiome only analysis, multivariable polytomous logistic regression models were used to calculate prevalence odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the association of oral microbial parameters (alpha-diversity and taxa presence/absence or relative abundance) with breast cancer and non-malignant breast disease. Alpha-diversity was modeled both as a continuous variable and using quartiles estimated from the distribution among the controls. For beta diversity, PCoA plots were generated using the first five PCoA vectors, which explained a total of 33.7%, 20.2%, 39.9%, and 59.4% of the variability in Bray Curtis, Jaccard, unweighted UniFrac, and weighted UniFrac distances, respectively. The difference of the overall beta-diversity distance matrices comparing breast cancer or non-malignant breast disease cases to controls was tested using MiRKAT (Microbiome Regression-Based Kernel Association Test).[19] For genera presence/absence analyses, we restricted to genera present in 5 to 95% of the population; and for the relative abundance analyses, we restricted to genera present in at least 50% of the population at a mean relative abundance greater than 0.1%. P-values were adjusted using Bonferroni correction for the taxonomic analyses. In the genus-level analysis, we highlighted any associations of genera from the red- (Porphyromonas, Tannerella, Treponema) and orange-complex (Fusobacterium, Prevotella, Peptostreptococcus, Streptococcus, Eubacterium, Campylobacter) periodontal pathogens with breast cancer and non-malignant breast disease.

Statistical models were adjusted for the following factors: age (continuous), study center (Komfo Anoyke Teaching Hospital, Korle Bu Teaching Hospital, or Peace and Love Hospital), body mass index (BMI, categorical), education (junior secondary school or lower, senior secondary school/some college or technical school or more, other or unknown), family history of cancer (yes, no, unknown), antibiotic use (within the last 30 days, more than 30 days/never, or missing), number of full-term pregnancies (0, 1–2, 3–4, 5+ pregnancies), smoking (yes, no, unknown), alcohol drinking (yes, no, unknown), and current hormonal contraceptive use (yes, no). As described later, observed ASVs were strongly, inversely associated with odds of breast disease, and therefore may serve as a confounder or mediator of the associations of taxa presence with disease. Therefore, we additionally evaluated the impact of adjustment for observed ASVs in the taxa presence models. A sensitivity analysis of the above associations of oral microbiome and breast cancer by excluding participants who took antibiotics within the last 30 days was conducted.

For the oral and fecal microbiome comparison, linear regression models were used to estimate the association of oral and fecal alpha diversity stratified by case status. Spearman correlation coefficients were used to estimate the correlations of the presence and relative abundance of the oral and fecal genera stratified by case status with Bonferroni corrected p-values. For the taxa presence analyses, we restricted to those taxa present in at least 10% of each group; and for the relative abundance analyses, we restricted to those taxa with a mean relative abundance of greater than 1% of the population. All statistical analyses were conducted using R, version 3.6.2.

Results

Oral microbiome, breast cancer, and non-malignant breast disease

Characteristics of participants are presented in Table 1. Compared to controls, breast cancer cases were more likely to be older, formally educated, never alcohol drinkers, have a family history of breast cancer, and have taken antibiotics within the last 30 days. Cases were less likely to be married, premenopausal, never tobacco users, currently use hormonal contraception, and have ever breastfed for more than one month. The three oral microbial alpha-diversity metrics were lower in both breast cancer and non-malignant cases compared with controls.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants in the Ghana Breast Health Study of breast cancer and non-malignant breast disease (N=881)

| Characteristics | Breast Cancer Cases | Non-malignant Cases | Controls | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 369) | (N = 93) | (N = 419) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Mean (SD) | N (%) | Mean (SD) | N (%) | Mean (SD) | N (%) | |

| Study Center | ||||||

| KATH | 123 (33.3) | 26 (28.0) | 247 (58.9) | |||

| KBTH | 69 (18.7) | 25 (26.9) | 62 (14.8) | |||

| PLH | 177 (48.0) | 42 (45.2) | 110 (26.3) | |||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age, y | 50.9 (12.2) | 39.7 (12.8) | 46.9 (13.1) | |||

| Married/living with partner | 192 (52.0) | 48 (51.6) | 250 (59.7) | |||

| Senior secondary or higher education | 112 (30.4) | 49 (52.7) | 102 (24.3) | |||

| Premenopausal | 155 (42.0) | 65 (69.9) | 236 (56.3) | |||

| Medical history | ||||||

| Family history of breast cancer | 27 (7.3) | 5 (5.4) | 12 (2.9) | |||

| Had no full-term pregnancies | 35 (9.5) | 26 (28.0) | 45 (10.7) | |||

| Took antibiotics within the last 30 days | 102 (27.6) | 19 (20.4) | 82 (19.6) | |||

| Age at menarche, y | 15.5 (2.6) | 14.8 (1.7) | 15.2 (1.9) | |||

| Ever breastfed >1 month | 316 (85.6) | 66 (71.0) | 370 (88.3) | |||

| Lifestyle characteristics | ||||||

| Never tobacco user | 350 (94.9) | 92 (98.9) | 415 (99.0) | |||

| Never alcohol drinker | 265 (71.8) | 70 (75.3) | 282 (67.3) | |||

| Currently using hormonal contraceptive | 101 (27.4) | 29 (31.2) | 129 (30.8) | |||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.3 (5.9) | 29.0 (12.6) | 27.7 (7.5) | |||

| Microbiome metrics | ||||||

| Observed ASVs | 137.5 (56.4) | 135.9 (43.5) | 179.2 (44.9) | |||

| Faith’s PD | 9.4 (3.0) | 9.4 (2.4) | 11.6 (2.1) | |||

| Shannon index | 4.7 (1.1) | 4.8 (0.9) | 5.2 (0.7) | |||

As shown in Table 2, oral microbial alpha-diversity was strongly, inversely associated with the odds of breast cancer and non-malignant breast disease compared with controls. For example, for every increase in 10 observed ASVs, the odds ratios were 0.86 (95% CI=0.83–0.89) and 0.79 (95% CI=0.73–0.85) for breast cancer and non-malignant breast disease, respectively, compared with controls. Similar trends were observed for Shannon index and Faith’s PD. Alpha-diversity estimates did not significantly differ when comparing the breast cancer cases to the non-malignant breast disease cases.

Table 2.

Association between oral microbiome alpha-diversity with breast cancer and non-malignant breast disease

| Breast cancer cases vs. controls | Non-malignant cases vs. controls | Breast cancer cases vs. non-malignant cases | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P-value | OR | 95% CI | P-value | OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Alpha-diversity | |||||||||

| Observed ASVs | |||||||||

| Continuous (10 ASVs per unit) | 0.86 | 0.83 to 0.89 | 4.15E-18 | 0.79 | 0.73 to 0.85 | 6.98E-11 | 1.02 | 0.96 to 1.08 | 0.4652 |

| Q1 | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Q2 | 0.33 | 0.21 to 0.50 | 1.72E-07 | 0.49 | 0.26 to 0.91 | 0.0244 | 0.65 | 0.34 to 1.24 | 0.1939 |

| Q3 | 0.28 | 0.18 to 0.43 | 1.44E-08 | 0.14 | 0.06 to 0.33 | 5.54E-06 | 1.58 | 0.65 to 3.83 | 0.3168 |

| Q4 | 0.21 | 0.13 to 0.33 | 3.23E-11 | 0.09 | 0.03 to 0.24 | 1.73E-06 | 2.55 | 0.87 to 7.50 | 0.0895 |

|

| |||||||||

| Faith’s PD | |||||||||

| Continuous | 0.73 | 0.68 to 0.78 | 2.31E-18 | 0.63 | 0.54 to 0.72 | 4.84E-11 | 1.03 | 0.93 to 1.14 | 0.5840 |

| Q1 | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Q2 | 0.30 | 0.20 to 0.46 | 2.57E-08 | 0.38 | 0.20 to 0.71 | 2.56E-03 | 0.91 | 0.47 to 1.76 | 0.7806 |

| Q3 | 0.29 | 0.19 to 0.45 | 3.60E-08 | 0.14 | 0.06 to 0.32 | 3.60E-06 | 1.85 | 0.77 to 4.47 | 0.1694 |

| Q4 | 0.22 | 0.14 to 0.36 | 2.07E-10 | 0.10 | 0.04 to 0.26 | 1.84E-06 | 2.33 | 0.84 to 6.47 | 0.1050 |

|

| |||||||||

| Shannon index | |||||||||

| Continuous | 0.49 | 0.40 to 0.61 | 1.53E-10 | 0.49 | 0.35 to 0.68 | 3.23E-05 | 0.86 | 0.64 to 1.15 | 0.3012 |

| Q1 | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Q2 | 0.53 | 0.35 to 0.79 | 0.0019 | 0.48 | 0.25 to 0.91 | 0.0257 | 0.91 | 0.47 to 1.79 | 0.7954 |

| Q3 | 0.30 | 0.19 to 0.48 | 4.46E-07 | 0.37 | 0.18 to 0.74 | 0.0051 | 0.66 | 0.31 to 1.43 | 0.2906 |

| Q4 | 0.40 | 0.26 to 0.61 | 3.04E-05 | 0.26 | 0.12 to 0.57 | 0.0008 | 1.22 | 0.53 to 2.81 | 0.6346 |

Adjusted for age (continuous), study center (Komfo Anoyke Teaching Hospital, Korle Bu Teaching Hospital, or Peace and Love Hospital), body mass index (BMI, categorical), education (junior secondary school or lower, senior secondary school/some college or technical school or more, other or unknown), family history of cancer (yes, no, unknown), antibiotic use (≤30 days ago, >30 days ago/never, or missing), number of full-term pregnancies (0, 1–2, 3–4, 5+ pregnancies), smoking (yes, no, unknown), alcohol drinking (yes, no, unknown), and current hormonal contraceptive use (yes, no). Abbreviations: ASVs, amplicon sequence variants; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; PD, Phylogenetic Diversity.

Overall beta-diversity from the four distance matrices was significantly different between breast cancer cases and controls, as well as between non-malignant breast disease cases and controls (all P<0.01), but not between breast cancer and non-malignant disease cases (all P>0.05), as indicated by MiRKAT models (Table 3). However, no visual clustering by case groups was detected in PCoA plots (Figure S3).

Table 3.

MiRKAT test for the association between oral microbiome beta-diversity matrices with breast cancer and non-malignant breast disease

| Breast cancer cases vs. controls | Non-malignant cases vs. controls | Breast cancer cases vs. non-malignant cases | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bray-Curtis | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.2046 |

| Jaccard | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.2041 |

| Unweighted UniFrac | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.4467 |

| Weighted UniFrac | <0.0001 | 0.0060 | 0.7040 |

Adjusted for age (continuous), study center (Komfo Anoyke Teaching Hospital, Korle Bu Teaching Hospital, or Peace and Love Hospital), body mass index (BMI, categorical), education (junior secondary school or lower, senior secondary school/some college or technical school or more, other or unknown), family history of cancer (yes, no, unknown), antibiotic use (≤30 days ago, >30 days ago/never, or missing), number of full-term pregnancies (0, 1–2, 3–4, 5+ pregnancies), smoking (yes, no, unknown), alcohol drinking (yes, no, unknown), and current hormonal contraceptive use (yes, no). Bonferroni adjusted p-value significance threshold for beta-diversity comparisons was p < 0.05/4 = 0.0125.

The associations for the presence of specific genera with breast cancer and non-malignant breast disease are presented in Table S1. The presence of 64 and 28 genera were significantly associated with breast cancer and non-malignant breast disease, respectively, compared with controls. No genera were significantly different comparing breast cancer to non-malignant breast disease. Particularly, the presence of the periodontal pathogens Porphyromonas (OR=0.02, 95% CI=0.003–0.18), Tannerella (OR=0.20, 95% CI=0.12–0.36), Prevotella.2 (OR=0.10, 95% CI=0.04–0.21), and Eubacterium..nodatum.group (OR=0.09, 95% CI=0.03–0.24) were strongly, inversely associated with the odds of breast cancer compared with controls. Treponema.2 (breast cancer OR=0.16, 95% CI=0.08–0.31, non-malignant breast disease OR=0.12, 95% CI=0.05–0.31), Peptostreptococcus (breast cancer OR=0.11, 95% CI=0.05–0.26, non-malignant breast disease OR=0.10, 95% CI=0.03–0.34), and Prevotella.1 (breast cancer OR=0.53, 95% CI=0.39–0.73, non-malignant breast disease OR=0.27, 95% CI=0.15–0.49) were associated with lower odds of both breast cancer and non-malignant breast disease compared with controls. After additionally adjusting for observed ASVs, only seven genera were significantly associated with breast cancer and none of these genera were periodontal pathogens, with no genera significantly associated with non-malignant breast disease, compared to controls.

The associations for the genus-level relative abundances with breast cancer and non-malignant breast disease are presented in Table S2. The relative abundance of seven and two genera were significantly associated with breast cancer and non-malignant breast disease, respectively, compared with controls. No genera were significantly different comparing breast cancer to non-malignant breast disease. Compared to controls, for every 1% increase in the relative abundance of periodontal pathogens Porphyromonas and Fusobacterium, the odds of being a breast cancer case were 0.83 (95% CI=0.77–0.90) and 0.91 (95% CI=0.88–0.95), respectively, and for every 1% increase in the relative abundance of Treponema.2, the odds were 0.69 (95% CI=0.59–0.80) for being a breast cancer case and 0.51 (95% CI=0.37–0.72) for being a non-malignant breast disease case.

When excluding participants who used antibiotics within the previous 30 days, alpha-diversity (Table S3), beta-diversity (Table S4), relative abundance, and presence/absence associations were minimally affected (data not shown).

Oral and fecal microbiome comparison by case status

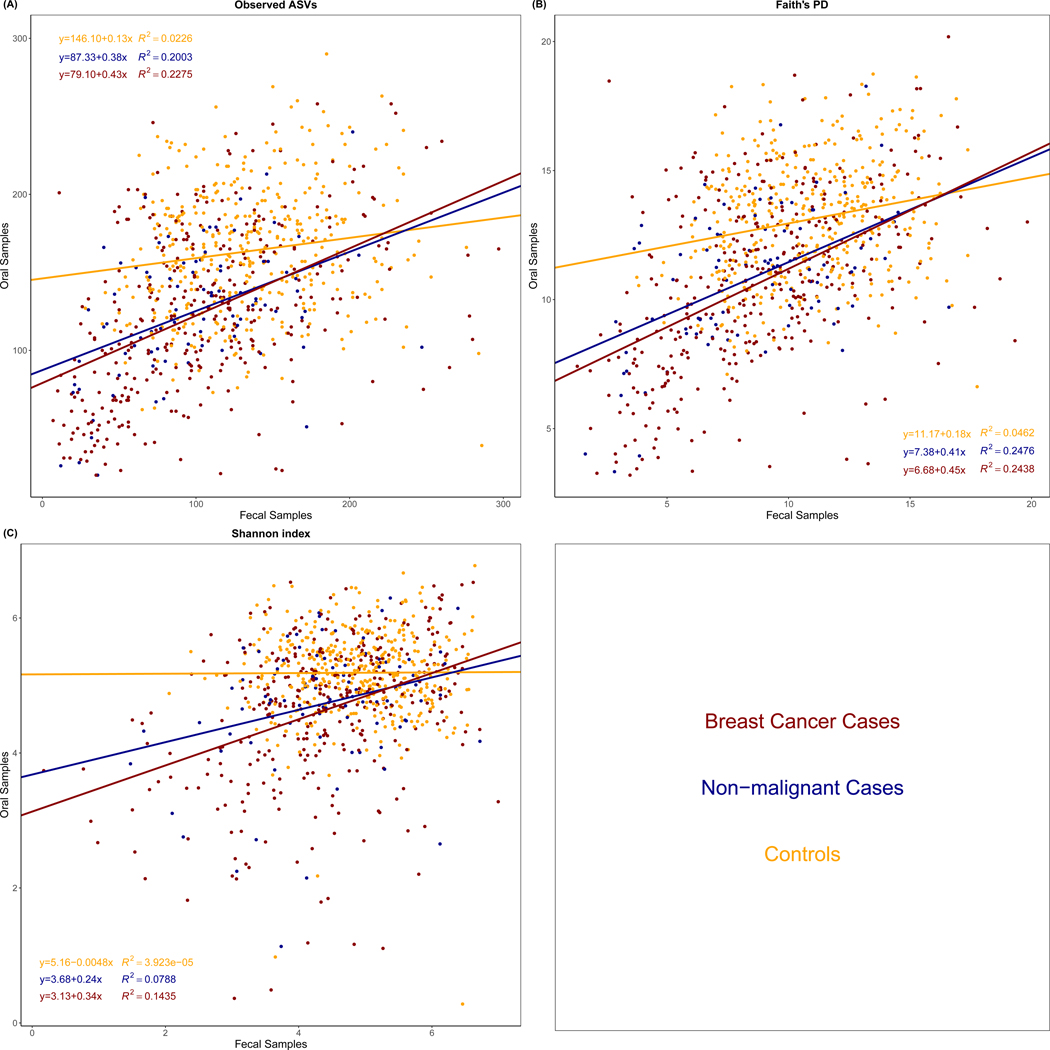

As shown in Figure 1, oral microbial alpha-diversity was positively associated with fecal microbial alpha-diversity in all groups (all P<0.05), except for the Shannon index in controls (P=0.901). However, the linear associations between oral and fecal microbial alpha-diversity were stronger within breast cancer and non-malignant breast disease cases compared to the associations with controls.

Figure 1.

Association of Observed Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) (A), Faith’s Phylogenetic Diversity (PD) (B), and Shannon index (C) from oral and fecal microbiome by case status. The linear relationship and R2 were estimated using linear regression models. The difference of R2 was test by student t-test. For observed ASVs, the p-values for the difference of R2 between breast cancer cases and controls, non-malignant breast disease cases and controls, and breast cancer cases and non-malignant breast disease cases were <0.0001, 0.0055, and 0.7562, respectively. For Faith’s PD, the p-values for the difference of R2 between breast cancer cases and controls, non-malignant breast disease cases and controls, and breast cancer cases and non-malignant breast disease cases were <0.0001, 0.0059, and 0.9670, respectively. For Shannon index, the p-values for the difference of R2 between breast cancer cases and controls, non-malignant breast disease cases and controls, and breast cancer cases and non-malignant breast disease cases were <0.0001, 0.0178, and 0.3595, respectively.

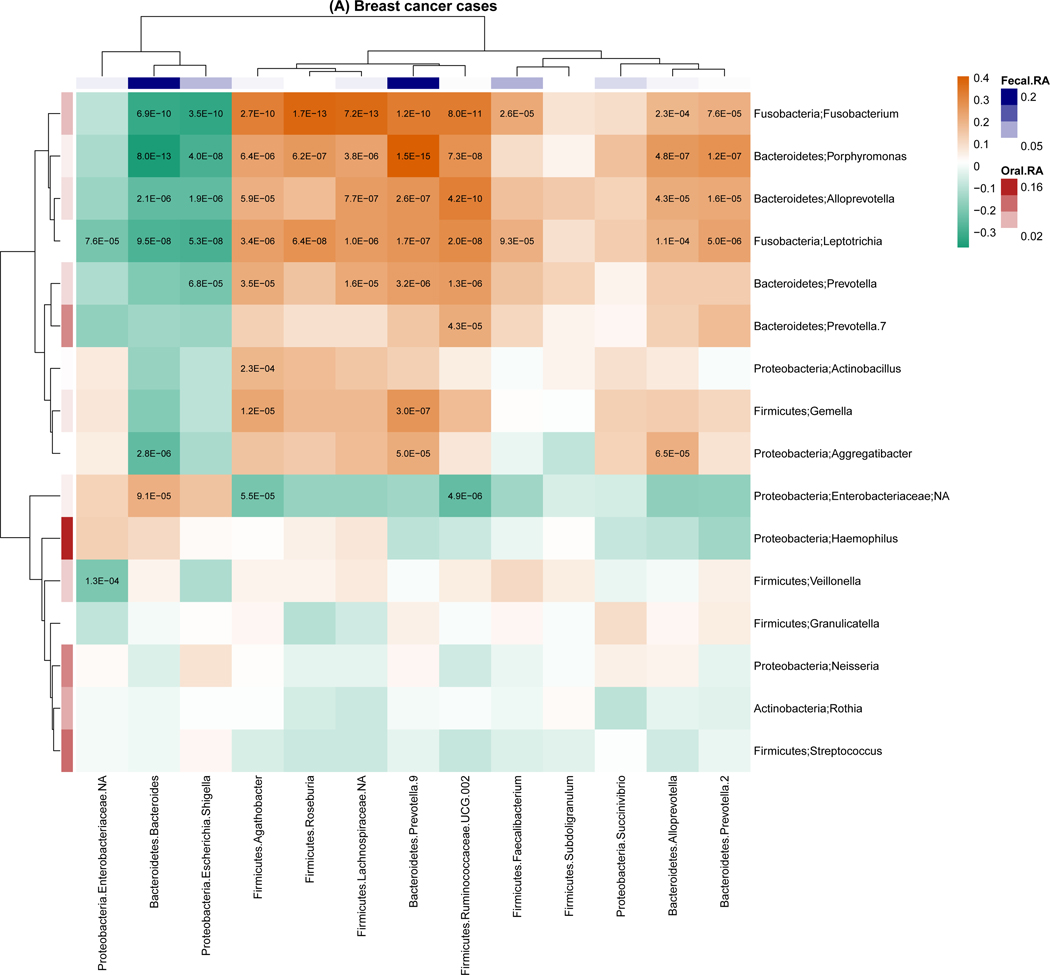

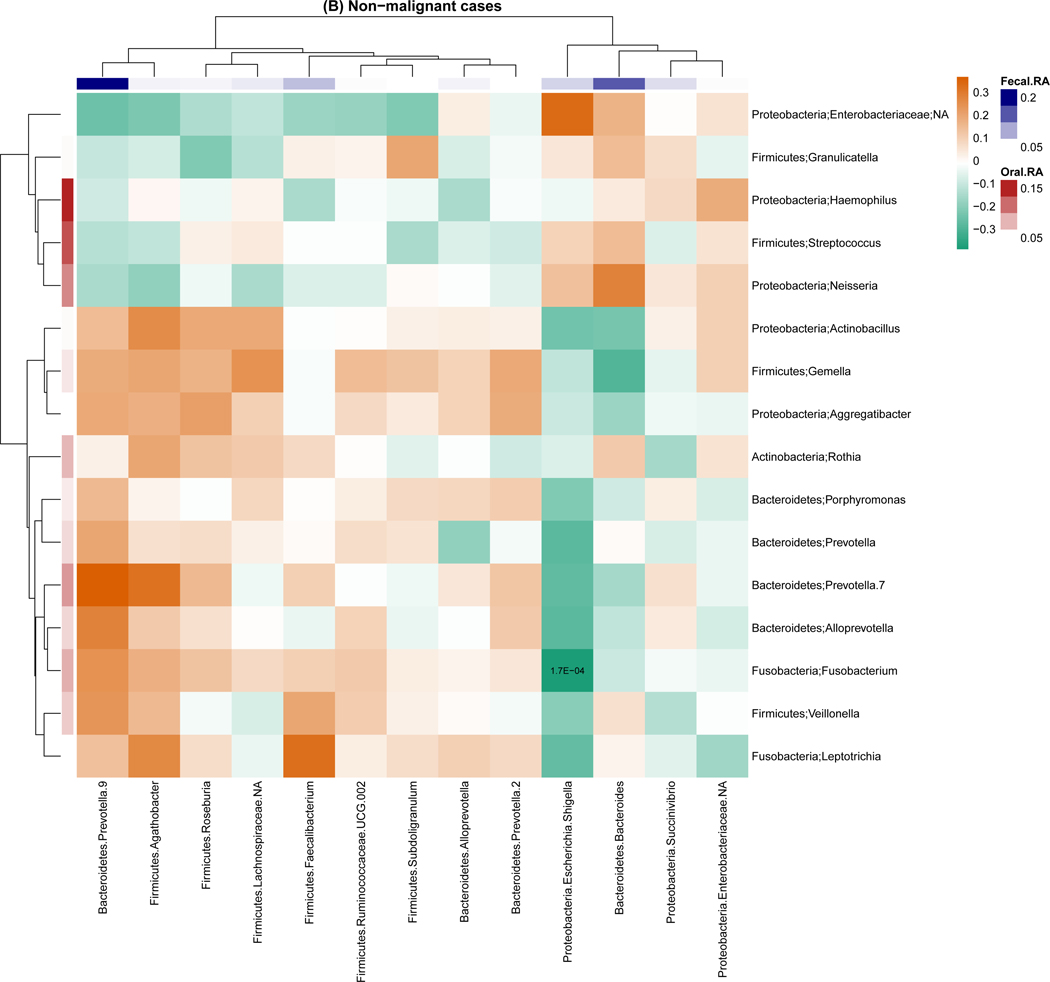

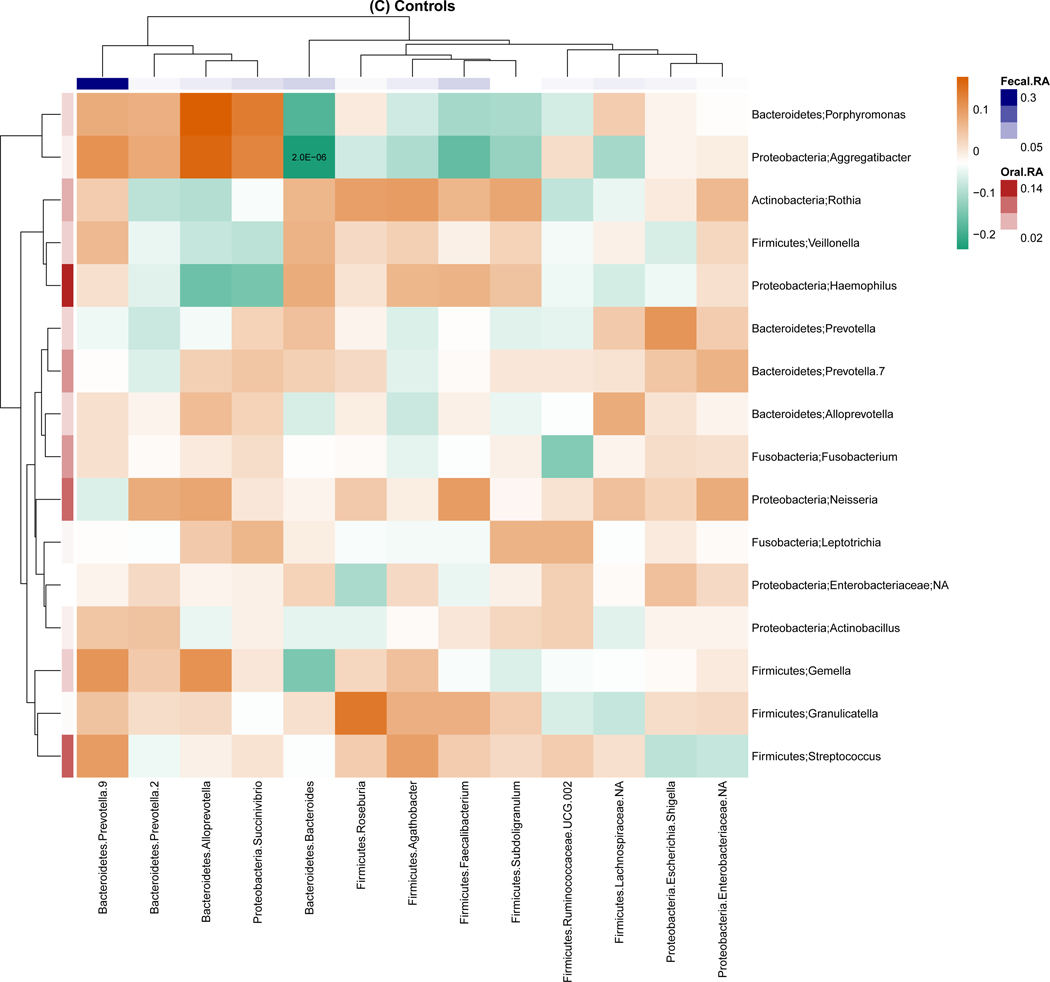

For genus-level relative abundance correlations between the oral and fecal microbiome (Figure 2), we found 54 pairs of oral and fecal genera were significantly correlated among breast cancer cases, but only one pair was significantly correlated among non-malignant breast disease cases and controls. The strongest correlations were observed for in breast cancer cases with correlation coefficients ranging from −0.37 to 0.41. Of note, the strongest correlation was between oral Porphyromonas and fecal Bacteroides (r=−0.37, P<0.001). Similar trends were observed for the correlation of the presence of genera for the oral and fecal microbiome, with 1,144, 45, and 28 pairs of oral and fecal genera significantly correlated in breast cancer cases, non-malignant breast disease cases, and controls, respectively. Most of these correlations were positive (Figure S4).

Figure 2.

Genus-level relative abundance correlations between the oral and fecal microbiome within breast cancer cases (A), non-malignant cases (B), and controls (C). Taxa were present with a mean relative abundance of greater than 1% of the population. Color of the cells (orange to green) indicates the scale of correlation coefficients, and the number in the cell is the corresponding p-value below the Bonferroni adjusted threshold p < 0.05/(13 × 16) = 2.4E-04. Fecal.RA, relative abundance of fecal taxa, Oral.RA, relative abundance of oral taxa.

Discussion

In the Ghana Breast Health Study, we found strong associations between the oral microbiome and breast cancer and non-malignant breast disease. Specifically, compared to controls, alpha-diversity was strongly, inversely associated with breast cancer and non-malignant breast disease, and microbial community composition was also associated with both conditions. The presence and relative abundance of multiple genera were strongly associated with breast cancer and non-malignant breast disease compared to controls, with several periodontal pathogens inversely associated with breast cancer and non-malignant breast disease, although the associations for the presence of the periodontal pathogens did not remain after adjustment for alpha-diversity. When comparing oral and fecal microbiome by case status, alpha-diversity and the presence and relative abundance of multiple genera were most strongly correlated among women with breast cancer, but weakly correlated among controls. Specifically, the oral periodontal pathogen Porphyromonas was strongly and inversely correlated with fecal Bacteroides, the fecal genus that was most strongly, positively associated with breast cancer in this population.[13]

Studies considering the relationship between oral microbiome and breast cancer are currently limited. Only one case-control study has previously been conducted which considered microbial differences in oral rinse samples from 55 breast cancer cases and 21 non-cancer patients. No significant differences were observed for measures of alpha-diversity, beta-diversity, or relative abundances of taxa between breast cancer and non-cancer patients.[12] However, due to the limited sample size, this study may have lacked sufficient power to detect associations. Lower alpha-diversity in breast cancer cases compared with controls has been also found in other body sites. Studies found that breast tumor tissue had significantly lower alpha-diversity compared with normal breast tissues.[20, 21] Similarly, the fecal microbiome has been found to be less diverse in women with breast cancer compared to those without.[22] In our previous study of the fecal microbiome in this same population, fecal alpha-diversity was also inversely associated with breast cancer and non-malignant breast disease. One possible mechanism for the inverse associations between alpha-diversity and breast cancer at multiple body sites is that a low bacterial richness occurs with a more pronounced inflammatory phenotype,[23] which may be associated with breast cancer risk.

Circulating estrogen levels may also play a role in the observed associations. Elevated concentrations of circulating estrogen are associated with a higher risk of breast cancer.[24] Estrogen exposure has also been shown to influence the immune response of human monocytes in the oral cavity[25] and may have an impact on the oral microenvironment. For example, estrogen appears to have a biphasic impact on periodontal disease pathology[26] where high estrogen levels during pregnancy modifies the gingiva and promotes gingivitis,[27] while low levels of estrogen leads to more frequent and more severe periodontal disease in postmenopausal women.[28] Women with periodontal disease, a common chronic inflammatory condition considered to be caused by the periodontal pathogens,[11, 29] have been reported to have null associations or modestly increased risk of breast cancer.[9, 30–32] We found that all of the bacteria from the ‘red complex’, as well as some bacteria from the ‘orange complex’, including the Prevotella.1, Prevotella.2, Eubacterium..nodatum.group, Peptostreptococcus and Fusobacterium, were inversely associated with breast cancer risk, however, this is in the opposite direction from that suggested by the periodontal disease and breast cancer literature[31, 32]. It is possible that differences in oral health and access to dental treatment in Ghana[33] may be related to the unexpected associations. It is also possible that the association for the presence of the periodontal pathogens was confounded by alpha-diversity. When observed ASVs were included in the model, no significant associations were detected for any of the periodontal pathogens. However, associations with the relative abundance of the periodontal pathogens were also observed which are less likely to be confounded by alpha-diversity. The underlying mechanism for this possible oral microbiome-breast cancer connection is likely a complex interaction across many known and other unknown factors and needs additional research.

Given that we observed similar associations between oral alpha- and beta-diversity with breast cancer as we did previously with the fecal microbiome,[13] we additionally evaluated the correlation between the oral and fecal microbiome stratified by case status. Studies have reported significant correlations between the fecal and oral microbiome. An analysis within the healthy individuals of the Human Microbiome Project showed that the community types (representing clusters of relative abundance profiles) of fecal samples were significantly associated with samples from within the oral cavity, and the strongest association was with the community types observed in saliva.[34] Another study of colorectal cancer screening showed that combining the data from fecal microbiome and oral microbiome increased the sensitivity to predict colorectal cancer compared to using the fecal microbiome alone.[35] Our study also found a statistically significant, positive correlation of alpha-diversity from oral and fecal samples which was stronger in the breast cancer and non-malignant breast disease cases than in the controls. Similar results were seen for the presence and relative abundance of specific genera; only a few oral and fecal genera were correlated in the control group, while many correlations were detected in breast cancer cases. Interestingly, the relative abundances of the periodontal pathogens Porphyromonas, Fusobacterium, and Prevotella were associated with fecal genera in cancer cases. The strongest negative correlation was found between oral Porphyromonas and fecal Bacteroides. Fecal Bacteroides had the strongest positive association with breast cancer in this same population[13] and is also involved in the activity of the gut bacterial encoded estrogen-deconjugating enzyme: β-glucuronidase and β-galactosidase.[36] Studies in mice showed that oral administration of Porphyromonas gingivalis can lead to systemic inflammation and serum metabolomic and fecal microbiome changes, [37, 38] with the relative abundance of fecal order Bacteroidales decreasing after Porphyromonas gingivalis was administered.[37] However, the underlying mechanisms of how the oral microbiome, particularly periodontal pathogens, may impact the fecal microbiome in humans have not been fully elucidated.

Our study was the first to investigate the association between the oral microbiome and breast disease in an African population, which is an underrepresented population in the published microbiome literature. Additionally, our study is a well-characterized case-control study with the largest sample size to date to investigate the association between the oral microbiome and breast cancer. However, limitations of this study should also be noted. First, participants in this study were limited to those who were previously included in the fecal microbiome study, so this study may be susceptible to the potential selection biases related to the women who agreed to provide feces, which has been described previously.[13] There was an uneven distribution of controls included from each study center, which may have impacted on the associations. For this reason, we adjusted for the potential confounding by study centers in all models. Moreover, both breast cancer and non-malignant breast diseases cases were more likely to have taken antibiotics within the last 30 days compared to controls. However, our sensitivity analyses suggest that this did not have a strong impact on our results. In addition, previous research has suggested that the oral microbiome is robust against antibiotic-induced disturbances and the oral microbiome typically recovers quickly after antibiotic treatment.[39] Second, our study is cross-sectional, so we are unable to evaluate the causality of the oral microbiome with breast cancer. Third, this study was not originally designed to assess non-malignant breast diseases, thus these cases may not represent the range of non-malignant breast diseases in this population, and we did not have detailed pathological information on diagnoses to conduct more detailed analyses among this population. Finally, since the oral and fecal samples in our study were processed at two different laboratories and sequenced at different depth, it is not possible to differentiate differences in these samples due to laboratory methods or body site (i.e., oral cavity versus gut).

In conclusion, our findings suggest that oral microbiome, similar to the fecal microbiome, is strongly and similarly associated with breast cancer and non-malignant breast disease cross-sectionally. Multiple genera, specifically some periodontal pathogens, are inversely associated with breast cancer and non-malignant breast disease. Additionally, the oral and fecal microbiome appear to be more correlated among women with breast cancer or non-malignant breast disease compared with controls. Future studies of the role of oral microbiome in breast cancer etiology with a prospective study design, and studies of the associations of oral and fecal microbiome with estrogen metabolites would be helpful to further understand these associations.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and impact.

Our study is a well-characterized case-control study with the largest sample size to date to investigate associations of the oral microbiome with breast cancer, and the first to investigate these associations in an African population. Our findings suggest that oral microbiome, similar to the fecal microbiome, is strongly and similarly associated with breast cancer and non-malignant breast disease, which motivate continued study of these associations in diverse population and further study of the underlying mechanisms.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program in the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Cancer Institute (NCI). The success of this investigation would not have been possible without exceptional teamwork and the diligence of the field staff who oversaw the recruitment, interviews and collection of data from study subjects. Special thanks are due to the following individuals: Korle Bu Teaching Hospital,Accra—Dr. Adu-Aryee, Obed Ekpedzor, Angela Kenu, Victoria Okyne, Naomi Oyoe Ohene Oti, Evelyn Tay; Komfo Anoyke Teaching Hospital, Kumasi— Marion Alcpaloo, Bernard Arhin, Emmanuel Asiamah, Isaac Boakye, Samuel Ka-chungu and; Peace and Love Hospital, Kumasi—Samuel Amanama, Emma Abaidoo, Prince Agyapong, Thomas Agyei-Ansong, Debora Boateng, Margaret Frempong, Bridget Nortey Mensah, Richard Opoku, and Kofi Owusu Gyimah. The study was further enhanced by surgical expertise provided by Dr. Lisa Newman of the University of Michigan and by pathological expertise provided by Drs. Stephen Hewitt and Petra Lenz of the National Cancer Institute Dr. Maire A. Duggan from the Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Canada. Study management assistance was received from Ricardo Diaz, Shelley Niwa, Usha Singh, Ann Truelove and Michelle Brotzman at Westat, Inc. We thank Maura Kate Costello of the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute for helping to create the graphical abstract. Appreciation is also expressed to the many women who agreed to participate in the study and to provide information and biospecimens in hopes of preventing and improving outcomes of breast cancer in Ghana. This work utilized the computational resources of the NIH HPC Biowulf cluster. (http://hpc.nih.gov)

Funding

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program in the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Cancer Institute (NCI).

List of abbreviations

- ASV

Amplicon Sequence Variant

- CI

Confidence Intervals

- CV

Coefficients of Variation

- Faith’s PD

Faith’s Phylogenetic Diversity

- ICC

Intraclass Correlation Coefficients

- MiRKAT

Microbiome Regression-Based Kernel Association Test

- NCI

National Cancer Institute

- OR

Odds Ratio

- PCoA

Principal Coordinates Analysis

- QC

Quality Control

Footnotes

Ethics Statement

All participants provided written informed consent. This study was approved by the Special Studies Institutional Review Board of the National Cancer Institute (NCI; Rockville, MD, USA; FWA #: 00005897 and IORG #: 00010), the Ghana Heath Service Ethical Review Committee and Institutional Review Boards at the University of Ghana Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research (Accra, Ghana; FWA #: 00001824 and IORG #: 0000908), the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (Kumasi, Ghana), and the School of Medical Sciences at Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital (Kumasi, Ghana).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Data Availability Statement

The sequencing data is available on the Sequence Read Archive (NCBI SRA) under BioProject ID PRJNA767189 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/767189). Further information is available from Thomas U. Ahearn (thomas.ahearn@nih.gov) upon request.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A: Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018, 68(6):394–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F: Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 2015, 136(5):E359–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eng A, McCormack V, dos-Santos-Silva I: Receptor-defined subtypes of breast cancer in indigenous populations in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2014, 11(9):e1001720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brinton LA, Figueroa JD, Awuah B, Yarney J, Wiafe S, Wood SN, Ansong D, Nyarko K, Wiafe-Addai B, Clegg-Lamptey JN: Breast cancer in Sub-Saharan Africa: opportunities for prevention. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2014, 144(3):467–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costello EK, Lauber CL, Hamady M, Fierer N, Gordon JI, Knight R: Bacterial community variation in human body habitats across space and time. Science 2009, 326(5960):1694–1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Human Microbiome Project C: A framework for human microbiome research. Nature 2012, 486(7402):215–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Human Microbiome Project C: Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature 2012, 486(7402):207–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung SD, Tsai MC, Huang CC, Kao LT, Chen CH: A population-based study on the associations between chronic periodontitis and the risk of cancer. Int J Clin Oncol 2016, 21(2):219–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freudenheim JL, Genco RJ, LaMonte MJ, Millen AE, Hovey KM, Mai X, Nwizu N, Andrews CA, Wactawski-Wende J: Periodontal Disease and Breast Cancer: Prospective Cohort Study of Postmenopausal Women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2016, 25(1):43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teles R, Teles F, Frias-Lopez J, Paster B, Haffajee A: Lessons learned and unlearned in periodontal microbiology. Periodontol 2000 2013, 62(1):95–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Socransky SS, Haffajee AD, Cugini MA, Smith C, Kent RL Jr., : Microbial complexes in subgingival plaque. J Clin Periodontol 1998, 25(2):134–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang H, Altemus J, Niazi F, Green H, Calhoun BC, Sturgis C, Grobmyer SR, Eng C: Breast tissue, oral and urinary microbiomes in breast cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8(50):88122–88138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Byrd DA, Vogtmann E, Wu Z, Han Y, Wan Y, Clegg-Lamptey JN, Yarney J, Wiafe-Addai B, Wiafe S, Awuah B et al. : Associations of fecal microbial profiles with breast cancer and nonmalignant breast disease in the Ghana Breast Health Study. Int J Cancer 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Brinton LA, Awuah B, Nat Clegg-Lamptey J, Wiafe-Addai B, Ansong D, Nyarko KM, Wiafe S, Yarney J, Biritwum R, Brotzman M et al. : Design considerations for identifying breast cancer risk factors in a population-based study in Africa. Int J Cancer 2017, 140(12):2667–2677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vogtmann E, Hua X, Zhou L, Wan Y, Suman S, Zhu B, Dagnall CL, Hutchinson A, Jones K, Hicks BD et al. : Temporal Variability of Oral Microbiota over 10 Months and the Implications for Future Epidemiologic Studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2018, 27(5):594–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sinha R, Abu-Ali G, Vogtmann E, Fodor AA, Ren B, Amir A, Schwager E, Crabtree J, Ma S, Microbiome Quality Control Project C et al: Assessment of variation in microbial community amplicon sequencing by the Microbiome Quality Control (MBQC) project consortium. Nat Biotechnol 2017, 35(11):1077–1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bolyen E, Rideout JR, Dillon MR, Bokulich NA, Abnet CC, Al-Ghalith GA, Alexander H, Alm EJ, Arumugam M, Asnicar F et al. : Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat Biotechnol 2019, 37(8):852–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, Gerken J, Schweer T, Yarza P, Peplies J, Glockner FO: The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res 2013, 41(Database issue):D590–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao N, Chen J, Carroll IM, Ringel-Kulka T, Epstein MP, Zhou H, Zhou JJ, Ringel Y, Li H, Wu MC: Testing in Microbiome-Profiling Studies with MiRKAT, the Microbiome Regression-Based Kernel Association Test. Am J Hum Genet 2015, 96(5):797–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klann E, Williamson JM, Tagliamonte MS, Ukhanova M, Asirvatham JR, Chim H, Yaghjyan L, Mai V: Microbiota composition in bilateral healthy breast tissue and breast tumors. Cancer Causes Control 2020, 31(11):1027–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith A, Pierre JF, Makowski L, Tolley E, Lyn-Cook B, Lu L, Vidal G, Starlard-Davenport A: Distinct microbial communities that differ by race, stage, or breast-tumor subtype in breast tissues of non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White women. Sci Rep 2019, 9(1):11940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goedert JJ, Jones G, Hua X, Xu X, Yu G, Flores R, Falk RT, Gail MH, Shi J, Ravel J et al. : Investigation of the association between the fecal microbiota and breast cancer in postmenopausal women: a population-based case-control pilot study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2015, 107(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le Chatelier E, Nielsen T, Qin J, Prifti E, Hildebrand F, Falony G, Almeida M, Arumugam M, Batto JM, Kennedy S et al. : Richness of human gut microbiome correlates with metabolic markers. Nature 2013, 500(7464):541–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Endogenous H, Breast Cancer Collaborative G, Key TJ, Appleby PN, Reeves GK, Travis RC, Alberg AJ, Barricarte A, Berrino F, Krogh V et al. : Sex hormones and risk of breast cancer in premenopausal women: a collaborative reanalysis of individual participant data from seven prospective studies. Lancet Oncol 2013, 14(10):1009–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jitprasertwong P, Charadram N, Kumphune S, Pongcharoen S, Sirisinha S: Female sex hormones modulate Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide-induced Toll-like receptor signaling in primary human monocytes. J Periodontal Res 2016, 51(3):395–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robinson JL, Johnson PM, Kister K, Yin MT, Chen J, Wadhwa S: Estrogen signaling impacts temporomandibular joint and periodontal disease pathology. Odontology 2020, 108(2):153–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu M, Chen SW, Jiang SY: Relationship between gingival inflammation and pregnancy. Mediators Inflamm 2015, 2015:623427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suri V, Suri V: Menopause and oral health. J Midlife Health 2014, 5(3):115–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yost S, Duran-Pinedo AE, Teles R, Krishnan K, Frias-Lopez J: Functional signatures of oral dysbiosis during periodontitis progression revealed by microbial metatranscriptome analysis. Genome Med 2015, 7(1):27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jia M, Wu Z, Vogtmann E, O’Brien KM, Weinberg CR, Sandler DP, Gierach GL: The Association Between Periodontal Disease and Breast Cancer in a Prospective Cohort Study. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2020, 13(12):1007–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shao J, Wu L, Leng WD, Fang C, Zhu YJ, Jin YH, Zeng XT: Periodontal Disease and Breast Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of 1,73,162 Participants. Front Oncol 2018, 8:601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shi T, Min M, Sun C, Zhang Y, Liang M, Sun Y: Periodontal disease and susceptibility to breast cancer: A meta-analysis of observational studies. J Clin Periodontol 2018, 45(9):1025–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kailembo A, Preet R, Stewart Williams J: Socioeconomic inequality in self-reported unmet need for oral health services in adults aged 50 years and over in China, Ghana, and India. Int J Equity Health 2018, 17(1):99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ding T, Schloss PD: Dynamics and associations of microbial community types across the human body. Nature 2014, 509(7500):357–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flemer B, Warren RD, Barrett MP, Cisek K, Das A, Jeffery IB, Hurley E, O’Riordain M, Shanahan F, O’Toole PW: The oral microbiota in colorectal cancer is distinctive and predictive. Gut 2018, 67(8):1454–1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kwa M, Plottel CS, Blaser MJ, Adams S: The Intestinal Microbiome and Estrogen Receptor-Positive Female Breast Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2016, 108(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arimatsu K, Yamada H, Miyazawa H, Minagawa T, Nakajima M, Ryder MI, Gotoh K, Motooka D, Nakamura S, Iida T et al. : Oral pathobiont induces systemic inflammation and metabolic changes associated with alteration of gut microbiota. Sci Rep 2014, 4:4828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kato T, Yamazaki K, Nakajima M, Date Y, Kikuchi J, Hase K, Ohno H, Yamazaki K: Oral Administration of Porphyromonas gingivalis Alters the Gut Microbiome and Serum Metabolome. mSphere 2018, 3(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zaura E, Brandt BW, Teixeira de Mattos MJ, Buijs MJ, Caspers MP, Rashid MU, Weintraub A, Nord CE, Savell A, Hu Y et al. : Same Exposure but Two Radically Different Responses to Antibiotics: Resilience of the Salivary Microbiome versus Long-Term Microbial Shifts in Feces. mBio 2015, 6(6):e01693–01615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The sequencing data is available on the Sequence Read Archive (NCBI SRA) under BioProject ID PRJNA767189 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/767189). Further information is available from Thomas U. Ahearn (thomas.ahearn@nih.gov) upon request.