Abstract

Approaches for optimizing medication use and enhancing medication experiences, including deprescribing, for older people living in long-term care homes are urgently needed. Through a multiphase initiative involving an environmental scan (2018) and two stakeholder forums (2019, 2020), we created a framework for developing and implementing sustainable deprescribing practices in this sector. Representatives from public advocacy, health care professionals, long-term care, pharmacy service providers, and regional health and public policy organizations in Ontario, Canada were consulted. We used behavioural science and implementation planning strategies to develop four target behaviours and 14 supporting actions; five of these actions were prioritized for further work. Throughout the phases, stakeholders committed to participation at various levels including ongoing implementation teams working to develop resources for the prioritized actions. A key element of success was attracting and sustaining engagement of a wide variety of relevant stakeholders from across the health system by leveraging best practices in stakeholder engagement. The approach used is described in detail so that it can be adapted and applied by others to plan large behaviour change initiatives.

Keywords: Deprescribing, Polypharmacy, Long-term care, Implementation science, Stakeholder engagement

1. Introduction

Approaches for optimizing medication use and enhancing medication experiences, including deprescribing, for older people are urgently needed.1, 2., 3 This is particularly salient for people living in long-term care (LTC) settings (herein referred to as LTC or LTC homes but may also be known in other jurisdictions as assisted living facilities or nursing homes) who experience polypharmacy and are prescribed potentially inappropriate medications at higher rates than their community-living counterparts.4,5 Deprescribing is the planned and supervised process of dose reduction or elimination of medication that may be causing harm or no longer be providing benefit.6 Recent studies suggest that there are many people living in LTC who are potentially overtreated and few have medication regimens deintensified.7, 8, 9, 10, 11 Integrating deprescribing into care processes in LTC aims to reduce the risks associated with polypharmacy and ultimately improve quality of life for residents.

Many interrelated factors influence deprescribing across care settings with barriers at person, provider, and health system levels.12 Examples noted in studies of LTC settings include resident and their families' lack of awareness about indication, potential harms of continuing medication, and deprescribing as an option; prescriber reluctance to change medication therapy; few opportunities or time for collaboration amongst staff, pharmacists, and prescribers; and lack of comprehensive information systems that provide resident health histories.13, 14, 15 To improve medication experiences16 for all people living in LTC, a widescale cultural shift is needed.

We sought to create a framework for developing and implementing sustainable deprescribing practices in LTC homes in Ontario, Canada. As of March 2020, Ontario's LTC homes provide care and income-adjusted subsidized accommodation for more than 75,000 people across 623 LTC homes.17 Individual LTC homes are owned and operated under three models: for-profit (58%), non-profit (26%) or municipal (public) (16%).17 Direct care for people living in these homes is provided primarily by personal support workers and nurses.18

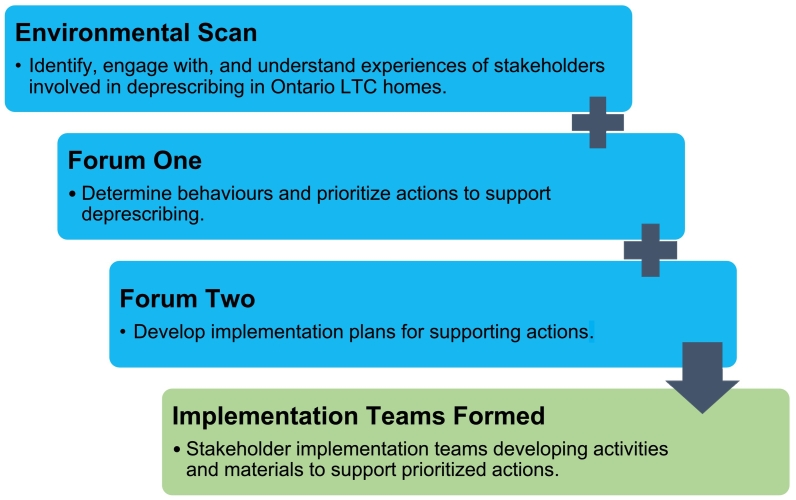

Our approach was anchored in behavioural science and implementation planning with a goal of engaging stakeholders and ultimately developing successful interventions to facilitate deprescribing behaviours. For our purposes, stakeholders were people or groups who can affect or are affected by an issue.19 In this case, we sought people who could represent one or more perspectives deemed to influence deprescribing in LTC. Herein, we describe an ongoing multi-phased initiative that began with an environmental scan and two stakeholder forums (Fig. 1). By describing our development process for the environmental scan and stakeholder forums and including instructive worksheets used in the forums, we anticipate others will be able to adapt these to customize similar initiatives. We present the resulting stakeholder-informed framework of desired behaviours and supporting actions toward embedding a culture of deprescribing in Ontario's LTC homes. We also provide data to demonstrate the initial reach and adoption of our stakeholder engagement efforts.

Fig. 1.

Ontario deprescribing in long-term care initiative: Program phases.

2. Approach

2.1. Environmental scan: stakeholder identification and preliminary engagement

We conducted an environmental scan in 2018 to build relationships with stakeholders across the Ontario LTC sector and to describe the current state of deprescribing knowledge and practices, lessons learned from deprescribing initiatives already implemented, and facilitators and barriers influencing deprescribing. This initiative was considered a community consultation and therefore was exempt from local research ethics board review.

One team member, acting as a ‘brand ambassador’, met with health care providers and directors of care from three local, non-profit LTC homes, with whom our team had collaborated on past projects. This was done strategically, consistent with bottom-up and middle-out approaches to organizational change,20 to begin by exploring perspectives of front-line health care providers and middle management who were involved in medication management functions within the LTC homes. Next, the team member met with people from organizations that represented the interests of health care providers or people connected to LTC homes of all ownership and operation models across the province identified in partnership with the Ontario Centres for Learning, Research and Innovation in LTC at Bruyère. Throughout these interactions, we identified additional key informants and organizations to be consulted. In addition, the team member delivered several interactive outreach events to organizations involved in the provision of LTC. A list of key stakeholders influencing deprescribing in LTC and a summary of the challenges and facilitators impacting deprescribing as a sustainable practice was collated from notes taken during these meetings and events and informed the planning of our first Forum. Additional information about the environmental scan can be accessed in The Ontario Deprescribing in Long-Term Care Forum June 2019 Report, available on our website, https://deprescribing.org/the-ontario-deprescribing-in-ltc-report/.21

2.2. Forum One

With our first Forum (June 2019), we sought to identify specific behaviours that would support deprescribing, and evidence-based actions that would facilitate those behaviours. Our main goal for this Forum was to enable stakeholders to precisely determine what behaviours needed to change within LTC homes to promote a culture of deprescribing. We developed an approach adapted from the Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) to guide the forum activities.22 The BCW framework provides a process for determining which evidence-based behaviour change strategies are applicable to a particular context and a systematic approach for analyzing available options for action. It considers the determinants of capability, opportunity and motivation in enacting behaviour change (the COM-B model) and links intervention types to evidence-based behaviour change techniques for intervention design. We adapted the approach to simplify explanations, make the content accessible and interesting to participants, and to focus on gaining consensus. This was done by refraining from asking participants to make direct linkages to these BCW determinants and not distinguishing between intervention types and behaviour change techniques, beginning the day with a presentation from a caregiver, and using techniques such as a World Café session (see Supplementary File S1 for agenda and worksheets; presentation materials available by request from authors).

Forum One was planned by a small group consisting of the project team between April–June 2019. Targeted invitations were sent to stakeholders identified through the environmental scan. Eligible participants were those able to represent one or more perspectives deemed to influence deprescribing in LTC including: people living in LTC and/or their families; direct care or service providers (e.g., health professionals practicing in LTC, other care providers, pharmacy services); advocacy groups (e.g., representing resident and caregivers, health professionals or other care providers); policymakers; and research or health system improvement experts. Table 1 provides a short description of each agenda item and lists its accompanying worksheets (Supplementary File S1) for both Forums.

Table 1.

Stakeholder forum organization and approaches.

| Agenda item |

Session description and worksheets⁎ |

|---|---|

| Forum One Purpose: Draft a framework of behaviours and actions that would support deprescribing in long-term care (LTC) | |

| Welcome | Introduction and goals for the Forum |

| A caregiver's perspective | Family caregiver shared perspectives about the shared responsibility for medication management in the context of a LTC home |

| Facilitators and challenges for deprescribing in LTC: Lessons learned from stakeholder consultations | Highlights from the environmental scan, including challenges and successful strategies to support deprescribing |

| Using the behaviour change wheel model to plan for deprescribing actions in LTC | Orientation to the concepts of behavioural problems, target behaviours and the COM-B model |

| Roundtable discussion: identifying and setting priorities for deprescribing behaviours in LTC | Participants assigned to small working groups designed to maximize diverse perspectives within each group; discussions structured to focus participants' energy on generating potential target behaviours for behavioural problems identified through the environmental scan; project team members circulated amongst the groups to provide guidance as needed; over a break, participants selected priority behaviours by voting using dots on flip charts (nominal group technique) Worksheet #1 – Identifying promising behaviours to support deprescribing Worksheet #2 – Specifying the target behaviour |

| Identifying actions that support deprescribing behaviour | Each working group was assigned one of the prioritized behaviours for which they freely generated details of supporting actions that could enable that behaviour Worksheet #3 - Identifying actions to support deprescribing behaviours |

| World café: arriving at prioritized actions | Using a World Café approach, participants assessed the appeal of the proposed supporting actions using the APEASE criteria (affordability, practicability, effectiveness, acceptability, side effects and equitability) to identify whether each action was very promising, promising or not promising Worksheet #4 – Prioritizing actions that facilitate behaviours to support deprescribing |

| LTC deprescribing framework overview | Summarized the day's activities and briefly revisited goal for the day |

| Implementation options – building a champion driven initiative for Fall | Introduced proposal to build a champion driven initiative to support action planning and behaviour change, including option to participate in planning next steps |

| Reflection and next steps |

Summary and appeal for feedback |

| Forum Two Purpose: Create an implementation plan to support actions that enable deprescribing behaviour change | |

| Welcome | Introduction and goals for the Forum |

| The June 2019 Deprescribing in LTC Forum – key results and next steps | Overview of the target behaviours and the actions identified at Forum One as being most promising to support those behaviours; relevant terms for the day clarified (e.g. target behaviour, supporting action, activities to make the action happen) |

| Generating momentum | Participant examples of activities undertaken since Forum One |

| Getting down to it – developing plans to make action happen | Participants assigned to working groups based on registration preferences and a desire to balance individual's expertise, perspective and the organizations they represented; a facilitator (staff, or member of the planning committee) was assigned to each working group to guide them through the process of generating an implementation charter Worksheet #1 – Implementation Charter |

| World Café – here is your chance to critique and build | Participants circulated through several small group discussions, using a World Café approach to discuss the risks and opportunities of the proposed implementation plans and identify participants interested in serving on implementation teams |

| Equipping the champions – how do we make this happen? | Large group discussion regarding potential implementation challenges |

| Focus on reach, adoption, sustainability and effectiveness: making change stick across XX LTC homes | Small group work to develop plans to maximize reach and adoption, ensure ongoing maintenance/sustainability of activities and brainstorm evaluation plans Worksheet #2 – Activity Planning and Evaluation |

| Reflection and next steps | Summary and appeal for feedback |

Worksheets can be found in Supplementary File S1.

After Forum One, we assessed the generated actions for fit with COM-B and aligned intervention types. Specifically, we: a) reviewed behaviours to determine the drivers (i.e., which COM-B components were best aligned)22; b) identified corresponding intervention types aligned with relevant COM-B components; c) mapped the supporting actions developed to the intervention types from the BCW (Table 2). The team prepared The Ontario Deprescribing in LTC Forum June 2019 Report outlining the environmental scan and Forum One proceedings.21 This report was reviewed by participants, posted online in November 2019 and distributed electronically to 34 stakeholder groups with encouragement to share within their networks.

Table 2.

Target behaviours, linked COM-B component and intervention types, supporting actions and implementation charter aim statements.

| Target behaviour | COM-B component and intervention type per behaviour change wheel | Supporting actions (Forum One)⁎ |

Aim statement (Forum Two) |

|---|---|---|---|

| People living in LTC and their families/ caregivers will participate in shared decision-making to establish and monitor goals of care with respect to medication use considering effectiveness, safety and non-drug alternative. |

Opportunity – social Restriction, environmental restructuring, modelling, enablement |

Use approaches like modelling to illustrate positive outcomes through story sharing (felt to be promising/very promising). |

Develop a package for home staff/family council/resident council will distribute to the resident/family/caregiver. The package will consist of testimonials (video/podcast/written), case studies, a discussion guide, and cue cards with questions to ask and recommendations for whom to ask the questions to and when. The goal of the package is to help persuade the resident/caregiver to tell the story of the resident/caregiver. The package will be a template that each home can customize (e.g., based on their size). |

| Capability – psychological Education, training or enablement |

Offer/develop educational resources for people living in LTC homes and their family/caregivers to inform them about their opportunities for contributions and to standardize approaches (felt to be promising/very promising). |

Standardize and disseminate a consistent, comprehensive process for shared decision making and responsibility in medication management clear for people living in LTC and their families (including an effective resource guide), and LTC management who can ensure consistent approaches. |

|

| Opportunity – physical Training, restriction, environmental restructuring, enablement |

Schedule timely medication-focused discussions with the people living in LTC homes/ families/ caregivers and the health care team (less promising due to affordability/practicability but worth considering). |

Not selected for Forum Two. |

|

| Opportunity – physical Training, restriction, environmental restructuring, enablement |

Develop regulations that mandate and monitor the person/ family/ caregiver involvement in care planning and medication review (new). |

Not selected for Forum Two. |

|

| Prescribers in every health care setting will document reasons for use, goals and timelines for each medication. |

Opportunity – physical Training, restriction, environment restructuring, enablement |

Incorporate relevant components (reason for use, goals of therapy, planned duration of use and date for review) into e-prescribing and electronic health records (felt to be promising with the caveats of affordability and possible inequity for those who are not technologically savvy). |

Develop a prioritized list of high-risk medications (for which a reason for use informs deprescribing) and their reasons for use that can be integrated in e-prescribing, pharmacy dispensing software, medication administration records in XX LTC homes. |

| Opportunity – physical Training, restriction, environment restructuring, enablement |

Develop regulations that mandate and monitor associated documentation standards and compliance (felt to be promising). |

Not selected for Forum Two. |

|

| Opportunity – physical Training, restriction, environment restructuring, enablement |

Enable medication information sharing via centralized electronic records (felt to be very promising). |

Not selected for Forum Two. |

|

| All health care providers and personnel will observe for signs and symptoms in the people they care for, reporting changes as a result of medication adjustments, or changes that might prompt review for deprescribing. |

Capability – psychological (knowledge) Education, training or enablement |

Provide education and training using tools that link signs and symptoms to medication-related effects (very promising). |

Frontline personnel (specifically personal support workers, but could extend to registered practical nurses, recreational therapists) will be able to identify people for medication assessment and potential deprescribing opportunities, particularly for those who: -are at high risk for falls -have an acute decline in function (e.g., sudden increase in assistance required to perform activities of daily living) |

| Opportunity – social AND Motivation - Reflective Restriction, environmental restructuring, modelling, enablement AND Education, persuasion, incentivization, coercion |

Use approaches like modelling to promote health care provider and personnel engagement through personal story sharing (very promising). |

Not selected for Forum Two. |

|

| Opportunity – physical Training, restriction, environmental restructuring, enablement |

Make tools to help monitor changes in signs and symptoms accessible at the point-of-care (promising). |

Not selected for Forum Two. |

|

| All members of the health care team will participate in conversations about deprescribing. | Capability – psychological (knowledge) Education, training or enablement |

Develop role descriptions to facilitate collaboration amongst the health care team (felt to be promising). |

Not selected for Forum Two. |

| Opportunity – social AND Opportunity- physical Restriction, Environmental Restructuring, modelling, enablement AND Training, restriction, environmental restructuring, enablement |

Create dedicated time and space for discussions during each shift, at care conferences, and as needed (felt to be very promising). |

Not selected for Forum Two. |

|

| Not applicable Action does not map to a COM-B intervention type |

Establish a monitoring and evaluation framework for the impact of health care provider and personnel collaborations on deprescribing, care plans, quality of life, retention and workload (felt to be promising). |

Develop a validated framework to be piloted in six LTC homes using a collaborative, stakeholder-engaged process that monitors the impact of deprescribing implementation. |

|

| Motivation – Reflective Education, persuasion, incentivization, coercion |

Recognize health care provider and personnel who identify signs and symptoms that lead to a deprescribing conversation (participants did not rate the promise of this option). | Not selected for Forum Two. |

Groups provided a consensus rating of each action as not promising, less promising, promising, very promising.

2.3. Forum Two

We hosted a second Forum (January 2020) to create champion-driven implementation plans (herein called implementation charters) to support operationalization of the actions that were identified in Forum One. Our approach was adapted from one used by the Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement (CFHI). We engaged champions in crafting the charters to ensure we generated activities that would be endorsed and implemented by those that could influence and support sustained behaviour change in Ontario's LTC homes.

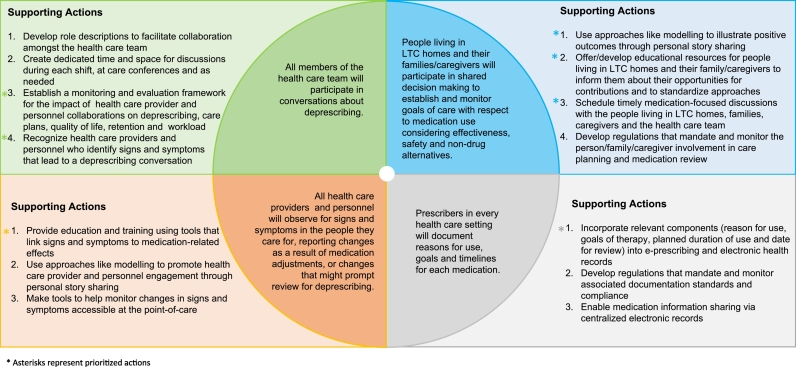

To build champion capacity and stakeholder engagement, we expanded our Forum planning team to include eight stakeholders who had attended the first Forum. Between August–December 2019, this committee planned the vision, objectives, and content. To determine stakeholders we would invite, we reviewed Forum One invitation lists, suggestions from planning committee members and people identified through other networking done by our team. Eligible participants were selected based on their potential to lead change as determined by previous work experience connected to the behaviours, their involvement in Forum One, and the organization's potential to connect with and influence other stakeholders in the province. During the registration process, people were asked to review the descriptions of each behaviour and related actions from Forum One, select and rank three actions that they or their organization could champion and in which they were interested in developing implementation plans at Forum Two. The top ranked actions became those prioritized for focus in Forum Two and are presented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Creating an environment where deprescribing is a sustainable component of medication management in LTC: Desired behaviours and supporting actions.

Following Forum Two, planning began for individual implementation charter teams to lead activities related to the most highly ranked actions. Stakeholders were invited to attend a 30-minute webinar (Feb 2020) to discuss next steps. At the webinar, we presented an overview of each implementation teams' charter and a proposed organizational structure for future phases. A call for volunteers to join a leadership committee that would oversee the work across individual implementation teams was issued.

3. Resources

The activities described here were supported with two staff (a pharmacist who conducted the environmental scan and assisted with Forum planning and evaluation - 0.2 FTE, and an administrative staff member who organized logistics and communication - 0.2 FTE) between October 2018 and March 2020. Additional costs were minimal as stakeholders covered the costs of their own attendance and there was no fee for room rental; we provided refreshments (lunch, snacks) and parking. Table facilitators were students, staff and volunteers who had previously worked with our team.

3.1. Feedback and Evaluation

We asked participants to complete a feedback form (with Likert-type and open-ended questions) at the completion of each Forum to gather input on the event logistics, and, for Forum One, on the actions they would be interested in taking on toward implementation of deprescribing, and for Forum Two, on the steps each would take to champion the implementation of specific activities.

We used the RE-AIM framework, specifically the reach and adoption components, to guide our overarching evaluation of the stakeholder engagement strategies we used.23 To examine reach, we collected the number of those we invited to both Forums and who participated. We also captured the number of website downloads of the report generated from our environmental scan and Forum One proceedings.21 To examine adoption, in addition to the responses we received through the feedback forms, we documented the number of Forum One participants who agreed to participate on the subsequent planning committee for Forum Two, leadership committee, and on individual implementation teams. In April 2020, we also emailed 54 people who either attended at least one of the Forums, or were sent the Forum One report, with a SurveyMonkey link inviting them to provide input about report distribution and activities resulting from the report or Forum participation.

4. Findings

4.1. Environmental scan

Twenty-two stakeholder discussions and nine outreach events were completed and summarized in the Forum One report.21 Eight categories of stakeholders were identified as influencing deprescribing culture in LTC: people living in LTC homes, their families and caregivers; prescribers (e.g., physician, nurse practitioner); health care providers (e.g., registered nurse, pharmacist, occupational and physiotherapists); front line personnel (i.e., provide direct person care and/or psychosocial support on a near daily basis like personal support worker, recreation therapists etc.); support services personnel (i.e., do not provide health care but interact with residents regularly like food or environmental services); LTC home administrators; policy makers; and professional bodies and advisory groups.

.15ptMany opportunities and challenges for deprescribing were identified. Opportunities included alignment with existing care structures (e.g., legislated quarterly medication reviews, annual care conferences with families, integration into quality improvement plans) and leveraging existing tools and resources (e.g., evidence-based deprescribing algorithms and guidelines). Challenges consistent with those documented in published literature included obtaining buy-in from prescribers,24 and variable willingness of residents25 and families, caregivers to engage in decisions about medications.26 Stakeholders also discussed the challenges of communication amongst health care providers (i.e., reliance on written communication due to variable schedules). More information about barriers and facilitators gathered through the environmental scan is summarized in The Ontario Deprescribing in LTC Forum June 2019 Report found on our website21

A key finding was the importance of engaging stakeholders representing a variety of perspectives in next phases of our work to provide proper context of the needs of LTC homes across Ontario. This included not only specific individual experiences, but also input from those that work in different LTC organizational structures (i.e., for-profit, non-profit or municipal).

4.2. Forum One

Of 65 targeted invitations to leaders of Ontario LTC stakeholder organizations, frontline health care professionals and public representatives, 23 participants representing public advocacy, health care professionals, LTC homes, pharmacy service providers, regional health and public policy organizations attended. Several health care providers represented pharmacy (4), nursing (4), medicine (2), and personal support workers (1). Four patient/public representatives participated as independents (2) or on behalf of advocacy organizations (2). A list of organizations and people who agreed to be acknowledged as participants across the entire initiative is included in Supplementary File S2.

Participants articulated and prioritized four target behaviours for which to further develop supporting actions. After Forum One, our project team determined that each of these behaviours aligned with at least one component of the COM-B model and all but one of the 14 supporting actions aligned with corresponding intervention types (Table 2).

Twenty-one of 23 participants provided feedback indicating overall satisfaction with the mix of perspectives, small working group discussions and the World Café session. Suggestions included more time for networking and introductions. All agreed that their opinions and experiences were respected and capitalized on during discussions. Eighteen of the 21 participants agreed that attendance improved their understanding of important actions that could support deprescribing behaviours within the Ontario LTC sector. Most committed to discussing deprescribing more regularly with health care professionals within their settings to raise awareness and encourage family involvement in medication reviews.

4.3. Forum Two

Forty-two targeted invitations were sent to leaders of Ontario LTC stakeholder organizations, frontline health care professionals and public representatives. Our planning committee was also contacted by seven people representing six organizations (including several physicians), and one public member, who requested an invitation to participate. In total, the Forum attracted 23 participants representing public advocacy, health care professional, LTC, pharmacy service providers, regional health and public policy organizations. Nine were participants from Forum One. Several health care providers represented medicine (6), pharmacy (5), and nursing (2). Four patient/public representatives participated as independents (1) or on behalf of advocacy organizations (3).

Based on participants' preferences, five supporting actions that addressed the four target behaviours were selected for the focus of the Forum ‘implementation team’ discussion groups. Table 2 outlines the target behaviours, supporting actions, links with COM-B model and the aim statements for each of the five resulting implementation teams. Eighteen Forum Two participants agreed to participate in at least one of these five ongoing implementation teams, with eight agreeing to take on leadership roles for this work.

Eighteen of 23 participants provided feedback about the Forum. Many enjoyed the small working group discussions, interaction and variety of stakeholders present. Suggestions included expanded time allotted for participants to understand each other's organizational mandates. Fifteen of 18 respondents reported that they felt confident that they could champion one or more activities to support deprescribing behaviours within the Ontario LTC sector. Participants stated their willingness to continue their involvement in their implementation teams to complete their team's charter and provide review and feedback on an ongoing basis.

4.4. February 2020 webinar

Thirty-three people attended the follow-up webinar. Of those who attended, two Forum One participants (who were unable to attend Forum Two) and one new individual asked to participate on the leadership and implementation teams.

4.5. Report uptake and use

Since the distribution of The Ontario Deprescribing in LTC Forum June 2019 Report21 in October 2019, it has been downloaded by 213 users (as of December 20, 2021). In our April 2020 survey to people who either attended at least one of the Forums or who had been sent the Forum One report by that date, 24 of the 54 people who were invited to provide input on its use, gave feedback. Fifteen of 24 respondents confirmed that they had circulated the report to colleagues by email, and two confirmed they had distributed it to approximately 12,000 members of their associations' databases via e-newsletter. They outlined a variety of roles in moving deprescribing initiatives forward (e.g., participating on the leadership and/or implementation teams, adding deprescribing presentations to conferences and webinars aimed at a variety of stakeholders, meeting with senior management teams to develop local deprescribing initiatives, developing deprescribing pilots in individual LTC residences, and sharing information within professional associations). Since the report was made public, our team has been invited to eight stakeholder organization meetings and to give five presentations at stakeholder conferences.

4.6. Implementation Team Work (2020/21)

The leadership team (including nine stakeholder members, excluding project investigators and staff) and five implementation teams (3–5 members each, total of 20 individuals, excluding project investigators and staff) began meeting in March 2020. Each implementation team focused on activities to support their assigned Aim Statement, as outlined in Table 2. These volunteer team members included a range of public representatives and advocates, health care providers, LTC and pharmacy provider organization representatives and regional health and public policy organizations.

Materials and activities to support prioritized actions were subsequently developed and are available on our website, https://deprescribing.org/resources/deprescribing-in-ltc-framework/. For shared decision-making, teams created a shared decision-making process guide, infographic, cue cards, fillable medication record and experience forms, a statement for admission and care conferences, and videos of example conversations. For the team focused on identifying residents in need of medication assessment, a process guide, infographic, and educational presentation materials were created.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, two members and one team, consisting primarily of physicians (which was focused on developing a prioritized list of high-risk medications and their reasons for use to support deprescribing), were unable to continue meeting. However, a significant portion of stakeholders remained engaged, attended regular meetings and contributed to ongoing planning throughout 2020 and into 2021. Five new members representing personal support worker educators joined the implementation team focused on identifying residents in need of medication assessment in 2021. A third team is contributing to the ongoing development of an evaluation approach for piloting these strategies in LTC homes.

5. Lessons Learned

Working with a wide range of stakeholders, we co-developed a framework of behaviours and supporting actions for integrating sustainable deprescribing practices in Ontario's LTC homes. Stakeholders embraced the initiative as indicated by their willingness to participate in the environmental scan, attend the Forums, and participate in planning and implementation teams. Sustained engagement is illustrated by the number of participants who remain actively involved. Further, as momentum built between Forums, new stakeholders approached our team with requests to be involved, including several physicians.

We believe our sustained stakeholder engagement results from the approach we used to build relationships prior to our Forums. During the environmental scan, one team member acted as a “brand ambassador” investing significant time and energy in networking with an emphasis on connecting with people in a way that sought to understand their unique circumstances. We purposely began by connecting with front line health care providers and middle managers responsible for medication management in LTC homes, representatives of residents and families, and then engaged other sector stakeholders. Through this process, our team identified which individuals from each organization were best suited to serve as champions.27

We experienced an important tension during the process of identifying champions. We desired widespread engagement and inclusion of many important voices with differing levels of direct patient care and leadership responsibilities to build ownership as these are ingredients for sustainable change. Yet, we were also cognizant of needing to keep the numbers of participants manageable and our scope aligned with our budget. We were also aware that front line staff or middle managers might struggle to secure approval to attend the Forums without organizational leaders feeling ownership. We attempted to reconcile the tension by including front line health care providers, many of whom also held middle management roles, in the Forums. In our subsequent implementation teams we continued to welcome new members to our teams because we recognized the importance of including front line care providers and middle management who would be responsible for implementing the resources within individual LTC homes.

We chose to use the BCW as a framework for planning Forum One because we saw value in first identifying targeted behaviours and then planning for interventions that would be both feasible and evidence-based in changing behaviour. The BCW has been used to develop many interventions across a range of topics yet most publications “tend to focus more on design than implementation and on content rather than process.”28

During our initial planning, we were unaware of examples where the BCW approach was used to identify and prioritize target behaviours with a wide group of stakeholders with little or no prior experience with it, in a short time frame. In our case, we designed our approach for a one-day format knowing this was the upper limit of time our stakeholders could reasonably commit.

More recently, others have shared their experiences using behavioural science, and the BCW specifically, to craft deprescribing interventions in primary care and hospital settings.29, 30, 31, 32 These teams, like ours, found that wide stakeholder engagement is a key component for success. Notably, each team approached their engagement with stakeholders slightly differently. Together, this body of work now offers examples from which others can draw. We are sharing the tools we created to support Forum One (worksheets adapted from Michie et al. and enhanced with objectives and facilitator instructions), and Forum Two (worksheets, objectives and facilitation instructions) to enable them to be used and further adapted by others undertaking related endeavors.

When designing Forum One, we recognized that our participants would generally be unfamiliar with behavioural science. Making behavioural science attractive to unfamiliar audiences can be challenging; the need to simplify terminology in the BCW for non-expert stakeholders has been reported previously.28 We attempted to adapt the terminology and approach from the BCW in ways to optimize its efficiency and accessibility for stakeholders attending our short one-day forum. We aimed to keep working groups focused on defining the problem first (target behaviour identification) before brainstorming solutions (supporting actions).

Given the many actions arising from Forum One, before Forum Two (which focused on implementation planning), we asked participants to identify actions which they or their organization could best support. This helped focus event planning on activities that participants had a vested interest in and could champion afterward. We also assigned facilitators to each working group to help keep participants focused on developing implementation charters and found the use of a structured charter template (Supplementary Text S1) helpful to facilitate discussions and commitment.

Two key limitations of our process are noteworthy for others who wish to apply the approach to this or other behavioural problems. First, we achieved varying degrees of completeness for implementation charters by the end of Forum Two, including varying levels of clear commitment to further action within each implementation team. This was mitigated by high rates of participation in subsequent meetings after Forum Two but suggests that training for facilitators and instructions for the day could be enhanced. Second, this process was largely conducted before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, through in-person forums. The spirit of our approach remains applicable though advances in people's familiarity with technology opens tremendous possibilities in terms of how future events could be delivered. While the logistics associated with online hosting of similar events would need to be determined, others could explore pre-recording of introductory content to allow flexible viewing options and shorter synchronous gatherings, alternating large and small groups through use of break-out discussion groups, and building interactivity with online voting systems etc.

With respect to future actions, our research team continues to facilitate the work of the implementation teams and we are conducting a more fulsome exploration of the use of the BCW in this context through semi-structured interviews with Forum participants. This will continue to inform our understanding of sustaining stakeholder engagement over time. We also aim to introduce and evaluate the tools and resources being created by our implementation teams within individual homes, which will further expand our understanding of creating self-sustaining change.

In summary, through this multi-phase intervention to develop a framework for deprescribing in Ontario LTC homes, we attracted and sustained a relationship with a wide variety of stakeholders. Relationship building and attempts to understand local, relevant context were important. Together with stakeholders, we articulated four target behaviours to facilitate deprescribing and 14 evidence-based supporting actions, five of which were prioritized for continued implementation planning. The approaches we adapted to use the BCW model and action planning can be used by others planning large behaviour change programs.

The following is the supplementary data related to this article.

Supplementary File S1: Forum One and Two Agendas and Worksheets

Presents agendas, facilitator and participant instructions, worksheets for the Forums.

Supplementary File S2: Participant List

Lists participants who provided written permission to acknowledge their participation and the names of the organization(s) they represented.

Sponsor's role

The sponsor was not involved in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, analysis or preparation of the manuscript.

Funding sources

This work was supported in part with funding from the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Centres for Learning, Research and Innovation in Long-Term Care hosted at Bruyère. The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Province.

Author contributions

Lisa M. McCarthy (conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, validation, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review, editing) Barbara Farrell (conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, projecta administration, supervision, validation, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review, editing) Pam Howell (conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, project administration, writing – review, editing) Tammie Quast (data curation, project administration, formal analysis, visualization, writing – review, editing).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Forum note-takers, facilitators and planning committee members (Leah Clement, Susan Conklin, David de Launay, Hannah Irving, Emily Galley, Lisa Richardson, Steve Smith, Brooklyn Ward), and research team staff and students who assisted with manuscript preparation and submission (Jeremy Rousse-Grossman, Daniel Dilliott, Lisa Richardson, Carmelina Santamaria and Sameera Toenjes).

Contributor Information

Lisa M. McCarthy, Email: lisa.mccarthy@utoronto.ca.

Barbara Farrell, Email: bfarrell@bruyere.org.

Pam Howell, Email: phowell@bruyere.org.

Tammie Quast, Email: tquast@bruyere.org.

References

- 1.Eliminating Medication Overload: A National Action Plan. Lown Institute; 2020. Working group on medication overload. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medication Without Harm - Global Patient Safety Challenge on Medication Safety. World Health Organization; 2017. pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hughes G.A., Rowett D., Corlis M., Sluggett J.K. Reducing harm from potentially inappropriate medicines use in long-term care facilities: we must take a proactive approach. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2021;17(5):829–831. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canadian Institute of Health Information . CIHI; 2018. Drug Use Among Seniors in Canada, 2016; pp. 1–69. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cateau D., Bugnon O., Niquille A. Evolution of potentially inappropriate medication use in nursing homes: retrospective analysis of drug consumption data. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2021;17(4):701–706. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farrell B., Pottie K., Rojas-Fernandez C.H., Bjerre L.M., Thompson W., Welch V. Methodology for developing deprescribing guidelines: using evidence and GRADE to guide recommendations for deprescribing. PLoS One. 2016;11(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zimmerman K.M., Linsky A.M. A narrative review of updates in deprescribing research. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(9):2619–2624. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niznik J.D., Hunnicutt J.N., Zhao X., et al. Deintensification of diabetes medications among veterans at the end of life in VA nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(4):736–745. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lega I.C., Campitelli M.A., Matlow J., et al. Glycemic control and use of high-risk antihyperglycemic agents among nursing home residents with diabetes in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Intern Med. March 1, 2021 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.0022. Published online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thorpe C.T., Sileanu F.E., Mor M.K., et al. Discontinuation of statins in veterans admitted to nursing homes near the end of life. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(11):2609–2619. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vu M., Sileanu F.E., Aspinall S.L., et al. Antihypertensive deprescribing in older adult veterans at end of life admitted to veteran affairs nursing homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(1):132–140.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.05.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linsky A., Gellad W.F., Linder J.A., Friedberg M.W. Advancing the science of deprescribing: a novel comprehensive conceptual framework. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(10):2018–2022. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palagyi A., Keay L., Harper J., Potter J., Lindley R.I. Barricades and brickwalls – a qualitative study exploring perceptions of medication use and deprescribing in long-term care. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0181-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turner J.P., Edwards S., Stanners M., Shakib S., Bell J.S. What factors are important for deprescribing in Australian long-term care facilities? Perspectives of residents and health professionals. BMJ Open. 2016;6(3) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lundby C., Glans P., Simonsen T., et al. Attitudes towards deprescribing: the perspectives of geriatric patients and nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(6):1508–1518. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shoemaker S.J., Ramalho de Oliveira D. Understanding the meaning of medications for patients: the medication experience. Pharm World Sci. 2007;30(1):86–91. doi: 10.1007/s11096-007-9148-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stall N.M., Jones A., Brown K.A., Rochon P.A., Costa A.P. For-profit long-term care homes and the risk of COVID-19 outbreaks and resident deaths. Can Med Assoc J. 2020;192(33):E946–E955. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.201197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Long-Term Care in Ontario: Sector Overview. Ministry of Health and Long-term Care; 2015. http://longtermcareinquiry.ca/wp-content/uploads/Exhibit-169-Long-Term-Care-in-Ontario-Sector-overview.pdf LTCI00071733–29. Accessed February 4, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schiller C., Winters M., Hanson H.M., Ashe M.C. A framework for stakeholder identification in concept mapping and health research: a novel process and its application to older adult mobility and the built environment. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):428. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taher D., Landry S., Toussaint J. Breadth vs. depth: how to start deploying the daily management system for your lean transformation. J Hosp Admin. 2016;5(6):90. doi: 10.5430/jha.v5n6p90. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farrell B., Howell P., McCarthy L. Bruyere Research Institute; Deprescribing Research Team: 2019. The Ontario Deprescribing in Long-Term Care Forum June 2019 Report.https://deprescribing.org/the-ontario-deprescribing-in-ltc-report/ [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michie S., Atkins L., West R. Silverback Publishing; 2014. The Behaviour Change Wheel: A Guide to Designing Interventions. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glasgow R.E., Vogt T.M., Boles S.M. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1322–1327. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heinrich C.H., Hurley E., McCarthy S., McHugh S., Donovan M.D. Barriers and enablers to deprescribing in long-term care facilities: a ‘best-fit’ framework synthesis of the qualitative evidence. Age Ageing. 2022;51(1) doi: 10.1093/ageing/afab250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sawan M.J., Jeon Y.H., Hilmer S.N., Chen T.F. Perspectives of residents on shared decision making in medication management: a qualitative study. Int Psychogeriatr. March 31, 2022:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S1041610222000205. Published online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sawan M., Reeve E., Turner J., et al. A systems approach to identifying the challenges of implementing deprescribing in older adults across different health-care settings and countries: a narrative review. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2020;13(3):233–245. doi: 10.1080/17512433.2020.1730812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miech E.J., Rattray N.A., Flanagan M.E., Damschroder L., Schmid A.A., Damush T.M. Inside help: an integrative review of champions in healthcare-related implementation. SAGE Open Med. 2018;6 doi: 10.1177/2050312118773261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bull E.R., Hart J.K., Swift J., et al. An organisational participatory research study of the feasibility of the behaviour change wheel to support clinical teams implementing new models of care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):97. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-3885-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kennie-Kaulbach N., Kehoe S., Whelan A.M., et al. Use of a knowledge exchange event strategy to identify key priorities for implementing deprescribing in primary healthcare in Nova Scotia, Canada. Evid Policy J Res Debate Pract. 2021 doi: 10.1332/174426421X16141831484350. Published online. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bai I., Isenor J.E., Reeve E., et al. Using the behavior change wheel to link published deprescribing strategies to identified local primary healthcare needs. Res Soc Adm Pharm. December 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2021.12.001. Published online. S1551741121003867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scott S., Twigg M.J., Clark A., et al. Development of a hospital deprescribing implementation framework: a focus group study with geriatricians and pharmacists. Age Ageing. 2020;49(1):102–110. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afz133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scott S., May H., Patel M., Wright D.J., Bhattacharya D. A practitioner behaviour change intervention for deprescribing in the hospital setting. Age Ageing. 2021;50(2):581–586. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaa169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary File S1: Forum One and Two Agendas and Worksheets

Presents agendas, facilitator and participant instructions, worksheets for the Forums.

Supplementary File S2: Participant List

Lists participants who provided written permission to acknowledge their participation and the names of the organization(s) they represented.