Abstract

We report here that the Escherichia coli replication proteins DnaA, which is required to initiate replication of both the chromosome and plasmid pSC101, and DnaB, the helicase that unwinds strands during DNA replication, have effects on plasmid partitioning that are distinct from their functions in promoting plasmid DNA replication. Temperature-sensitive dnaB mutants cultured under conditions permissive for DNA replication failed to partition plasmids normally, and when cultured under conditions that prevent replication, they showed loss of the entire multicopy pool of plasmid replicons from half of the bacterial population during a single cell division. As was observed previously for DnaA, overexpression of the wild-type DnaB protein conversely stabilized the inheritance of partition-defective plasmids while not increasing plasmid copy number. The identification of dnaA mutations that selectively affected either replication or partitioning further demonstrated the separate roles of DnaA in these functions. The partition-related actions of DnaA were localized to a domain (the cell membrane binding domain) that is physically separate from the DnaA domain that interacts with other host replication proteins. Our results identify bacterial replication proteins that participate in partitioning of the pSC101 plasmid and provide evidence that these proteins mediate plasmid partitioning independently of their role in DNA synthesis.

Replication of the Escherichia coli chromosome is initiated when the DnaA protein binds to specific sequences (DnaA boxes [2]) within the oriC (replication origin) region of the chromosome and opens the DNA helix, after which the DnaB helicase and the DnaC protein (46) are loaded at 13-mer sequences within the origin (8) through interaction with DnaA (26). The DnaB protein then proceeds to unwind the helix in advance of the replication fork (23), interacting also with the primase, DnaG (25), and DNA polymerase III (PolIII) holoenzyme (21, 31), and consequently helping to bring other components of the replication machinery to the origin.

Replication of plasmid pSC101 additionally requires the plasmid-encoded RepA protein, which binds to a region (the plasmid origin of replication) that includes binding sites for DnaA and 13-mers for DnaB/C entry. Also included in the origin region is a binding site for integration host factor, which is conditionally required for plasmid DNA replication (4), and the par locus, which accomplishes inheritance of plasmids in populations of dividing cells (28). Replication of pSC101 has been demonstrated to require the host DnaA and DnaG proteins (18, 14), and pSC101 replication is inhibited more rapidly than chromosome replication in dnaB and dnaC temperature-sensitive strains grown at an elevated temperature (17). The plasmid-encoded RepA protein has been shown to interact with the host-encoded DnaA, DnaB, and DnaG proteins in vitro as well as with the tau subunit of the PolIII holoenzyme (24, 25, 31, 33).

Earlier work has led to the proposal that partitioning of pSC101 is mediated by the same origin region multicomponent DNA-protein complex that accomplishes plasmid DNA replication (i.e., the Rep-Par complex [4, 20, 29]) but that the partition and replication functions of this complex are distinct (13, 20, 29). Factors affecting overall plasmid DNA superhelicity (30) or altering localized supercoiling in the pSC101 origin region (3, 13) can stabilize the inheritance of par deletion plasmids, possibly by enhancing the formation of the complex (20). Additionally, mutant forms of the RepA protein, which is a component of the origin complex, can promote plasmid stability (4) independently of its role in plasmid DNA replication (13, 45). Here we show that other components of the pSC101 origin region complex, the host replication proteins DnaA and DnaB, also mediate pSC101 partitioning and that their effects on partitioning are distinct from their roles in DNA replication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and general methods.

Bacterial strains and plasmids are listed in Table 1. Unless otherwise stated, bacteria were grown in Luria broth (LB) medium. Antibiotics (Sigma) were used at concentrations of 20 μg/ml (ampicillin and chloramphenicol) and 30 μg/ml (kanamycin). Plasmid DNA was isolated either by the method of Holmes and Quigley (19) or by Triton X-100 (12) or alkaline lysis (37).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| PM191 | recA, C600 derivative | 27 |

| SC1148 | lacI relA spoT1 thi-1 | 32 |

| WM448 | dnaA(Ts)46 | 44 |

| PC8 | dnaB(Ts)8 | 9 |

| HfrH165/70 | dnaB(Ts)70 | 7 |

| RS162 | dnaB(Ts)252 | 38 |

| PC2 | dnaC(Ts) | 9 |

| PC3 | dnaG(Ts) | 9 |

| HC194 | dnaN(Ts)159 | 35 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCM301 | pSC101 repA(Ts)46 par+, Apr | 45 |

| pCM302 | pSC101 repA(Ts)46 par deleted, Apr | 45 |

| pPM30 | pSC101 wild-type repA par+, Apr | 28 |

| pDLC8 | pSC101 repA par+, Kmr | 13 |

| pDLC6 | pSC101 repA par deleted, Kmr | 13 |

| pPM24 | pSC101 repA par deleted, Kmr | 28 |

| pHI1249 | pGZ119HE wild-type repA under tac control, Cmr | 20 |

| pBR322 | ColE1-type origin | 6 |

| pCM707 | pBR322 with DnaA, Apr | 29 |

| pETDnaB | pET11a with DnaB, Apr | D. Bramhill |

| pMJRDnaB | pBR322 with DnaB, Apr | 34 |

| pPL184 | DnaG under Lpl, Apr | 40 |

| pETTau | pET with PolIII tau subunit | 31 |

| pACYC184 | p15A, Cmr, Tcr | 10 |

| pACYCDnaA | pACYC184 with wild-type DnaA | 43 |

| pACDnaAA31T | pACYC184 with mutant DnaA | 43 |

| pACHA200 | pACYC184 with mutant DnaA | 42 |

| pACDnaAG287S | pACYC184 with mutant DnaA | 43 |

| pACDnaAL447W | pACYC184 with mutant DnaA | 43 |

| pACDnaAM435T | pACYC184 with mutant DnaA | This paper |

| pACDnaAD237-378 | pACYC184 with deletion of DnaA | This paper |

| pACDnaA001-31 | pACYC184 with mutant DnaA | This paper |

| petDnaBts8 | pET11a with mutant DnaB, Apr | 36 |

| petDnaBts70 | pET11a with mutant DnaB, Apr | 36 |

| petDnaBts252 | pET11a with mutant DnaB, Apr | 36 |

Plasmid construction.

DNA digestion by restriction endonucleases was performed according to protocols obtained from the supplier (New England Biolabs). Derivatives of pACYCdnaA (43) that contained the DnaA deletion D237-378 (41) and the DnaA mutation T435M (42) were constructed by digesting each plasmid with EcoNI and RsrII, exchanging the gel-purified (Qiagen) wild-type DnaA-containing fragment for the mutant fragment, and ligating the ends with T4 DNA ligase (Life Technologies, Inc.). The fragment encoding the membrane binding domain of DnaA was inserted into the same plasmid and sites; however, the sites were made blunt ended with T4 DNA polymerase (Life Technologies) and ligated to the similarly made blunt-ended EcoRI-to-HindIII fragment of pMZ001-31 (which contains DnaA with mutations R360E, R364E, and K372E [16]).

Transformation assays, segregation rates, and plasmid copy number.

Cells containing the pSC101 derivatives were transformed by using standard procedures (11) with plasmids expressing the various host replication proteins and plated on LB plates containing antibiotics selective for either the incoming plasmid or both plasmids. Plasmid stability (28) and copy number (5, 45) were determined as described previously; segregation analysis was performed at the temperatures indicated. The LD50 (the antibiotic concentration required to kill 50% of the cells) was used to assess the copy number for Apr plasmids (45). The rate-of-loss experiments were performed as previously described (45).

Protein concentrations.

Replication proteins were expressed at intermediate levels from constructs made for overexpression of those proteins but maintained in a noninduced state. pCM707 is an Apr derivative of a pACYC plasmid shown previously to produce five times the normal amount of DnaA protein (1). Various DnaB-overexpressing plasmids were tested, and the amounts of DnaB produced under noninduced conditions were monitored by Western blotting. For detection of DnaB and DnaG proteins, we used antibodies kindly provided by D. Bramhill and K. Marians, respectively. For Western blot analysis, routinely 0.7 OD600 (optical density at 600 nm) units of exponentially growing cells were lysed and separated on a sodium dodecyl sulfate–10% polyacrylamide gel (37) run on a Bio-Rad Protean II; Western analysis was performed as recommended by Promega, using a 1:10,000 dilution of the anti-DnaB or anti-DnaG antibody in Tris-buffered saline-Tween 20 (20 mM Tris [pH 7.6], 0.137 M NaCl, 0.17% Tween 20) with 1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma) and a 1:20,000 dilution of the horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (Promega). Protein recognized by the antibody was visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Renaissance; NEN Dupont) and scanned on a PDI densitometer (20).

RESULTS

pSC101 stability in cells having limited DnaB activity.

We wished to examine the effects of mutations in the essential E. coli replication proteins DnaA, DnaB, DnaC, DnaG, and DnaN—some of which have been shown to interact specifically with the plasmid-encoded RepA protein—on plasmid partitioning. While temperature-sensitive mutations in these proteins have been isolated, it is not possible to carry out extended culture of the mutant bacteria at temperatures that inactivate the proteins, which are required for both chromosomal and plasmid DNA replication. However, it has long been recognized that temperature-sensitive proteins have a gradation of activity throughout a wide temperature range and that bacteria containing temperature-sensitive mutations in proteins essential for growth commonly show detectable phenotypic effects even when cultured at permissive temperatures (14, 47). We therefore investigated whether temperature-sensitive mutations in host replication proteins affected plasmid partitioning during continuous culture at temperatures that permit DNA replication, choosing for each mutant the highest temperature that allows cell growth to proceed (17).

As seen in Table 2, the wild-type pSC101 plasmid replicon was entirely stable in E. coli cells carrying temperature-sensitive mutations in the dnaA, dnaC, dnaG, or dnaN gene when cultured at 35°C, the highest tested temperature that permits cell growth. However, the same plasmid was highly unstable in all tested dnaB mutant strains cultured at 30°C, which was the highest temperature that allowed cell growth in these mutants. The observed instability in the dnaB(Ts)8 strain was reversed by concomitant overexpression of the DnaA protein. Notwithstanding the destabilizing effects of dnaB mutations on plasmid inheritance during growth at 30°C, plasmid copy number, as measured by LD50 (45), was unchanged compared to dnaB+ strains cultured at the same temperature and was higher than the copy number seen at the same temperature in dnaA and dnaC temperature-sensitive strains {LD50 for pPM30, 200 μg/ml in wild-type cells, 250 μg/ml in PC8 [dnaB(Ts)8], 100 μg/ml in WM448 [dnaA(Ts)46], and 125 μg/ml in PC2 [dnaC(Ts)]}.

TABLE 2.

Effects of temperature-sensitive mutations in dnaA or dnaB on stability of the wild-type pSC101 plasmid, pDLC8

| Strain or genotype | Stabilitya (% of cells containing plasmid) after growth for:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| 20 generations | 40 generations | |

| PM191 | ND | 100 |

| dnaA(Ts)46b | ND | 98 |

| dnaB(Ts)8c | 78 | 50 |

| dnaB(Ts)8/pCM707 (DnaA)d | 100 | ND |

| dnaB(Ts)70c | 50 | ND |

| dnaB(Ts)252c | 20 | ND |

| dnaC(Ts)b | ND | 100 |

| dnaG(Ts)b | ND | 100 |

| dnaN(Ts)b | ND | 100 |

Cultures were grown in the absence of selection. Results are averages of three independent experiments. ND, not determined.

Grown at 35°C.

Grown at 30°C.

Grown at 30°C in LB with selection for the DnaA-expressing plasmid.

Partition without replication.

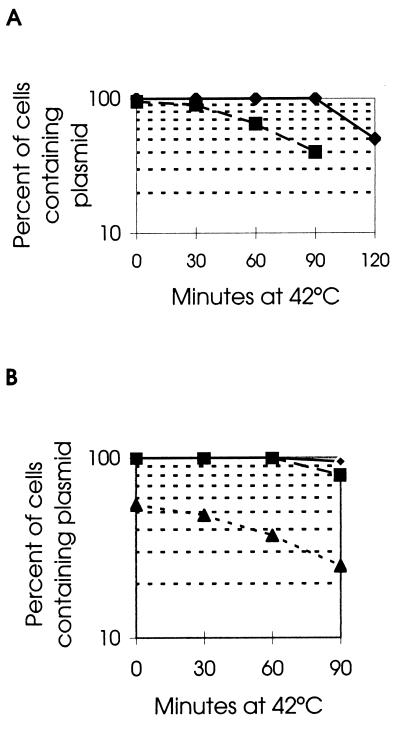

Cessation of pSC101 DNA replication consequent to a temperature-sensitive mutation in RepA yields plasmid-free cells only after the intracellular pool of nonreplicating plasmids has been diluted during several cell divisions, i.e., equipartition (45). However, when the pSC101 replicon lacks a par locus, shutoff of replication by inactivation of RepA causes loss of plasmids from half of the population during the first cell division (45) (Fig. 1A). This phenotype (i.e., the segregation of a nonreplicating cellular pool of pSC101 plasmids as a unit), which reflects loss of plasmid partition functions (20), was used to investigate the effects of host replication mutations on plasmid partitioning.

FIG. 1.

Rate of loss of pSC101 plasmids when replication ceases. Cells containing the plasmids were grown at the permissive temperature (30°C) with selection for the plasmid and then diluted into warm medium without antibiotic and grown at 42°C for the indicated times. The percentage of plasmid-containing cells was monitored by plating the cells at 30°C without selection and then picking onto plates with selection for the pSC101 plasmid; the number of total colonies was monitored to determine the number of cell divisions after the shift in temperature. Note that the y axis is a log scale. (A) pSC101 repA(Ts) plasmids. Squares, percentage of cells containing par+ pCM301; diamonds, percentage of cells containing par deletion plasmid pCM302 (45). (B) Host replication mutant temperature-sensitive strains with wild-type pSC101. The percentages of cells containing pDLC8 in dnaA (WM448, dnaA46 [44]), dnaB (PC8, dnaB8 [9], and HfrH165, dnaB70 [7]), dnaG (PC3, dnaG3 [9]), or dnaN (HC194, dnaN159 [35]) strains were identical and are represented by diamonds; the percentages of cells containing pDLC8 in dnaC (PC2, dnaC2 [9]) are represented by squares; triangles represent pDLC8 in the dnaB(Ts)252 strain (RS162 [38]).

In bacteria containing temperature-sensitive mutations in host replication genes, DNA synthesis stops either immediately upon shift to a nonpermissive temperature (fast-stop mutants) or at initiation of the next replication round (slow-stop mutants) (22). As the nonreplicating mutant cells continue to divide for several generations in both cases (48), the effects of host replication gene mutations on plasmid partitioning can be assessed by investigating plasmid segregation during this period. As seen in Fig. 1B, cessation of replication following a shift to the nonpermissive temperature of bacteria mutated in dnaA, dnaC, dnaG, or dnaN, whether slow-stop or fast-stop mutations, allowed equipartition of the plasmid pool. Two dnaB mutants that we tested, PC8 (dnaB8 [9]) and HfrH165 (dnaB70 [7]), both of which showed the fast-stop phenotype, also showed equipartition of pSC101 plasmids (Fig. 1B). However, loss of plasmids from half of the population occurred immediately upon the temperature shift of RS162, the dnaB252 (38) mutant strain, indicating a unique effect of this dnaB mutation on plasmid partitioning. Interestingly, the slow-stop mutation producing this partitioning defect has less immediate effects on DNA replication than the two dnaB fast-stop mutations that we studied (38) (Fig. 1B).

Stabilization of plasmids by DnaB overexpression.

Deletion of the par locus (28) (Table 3) or overproduction of the RepA protein (20) (Table 4) can result in unstable inheritance of pSC101 plasmids. Overexpression of DnaB at 4 to 10 times the normal level (as determined by Western blot analysis) was found to reverse both instances of plasmid instability (Tables 3 and 4), as was observed previously for DnaA (20). In contrast, overexpression of other host proteins that also interact directly with RepA (i.e., DnaG and the tau subunit of PolIII holoenzyme) had no stabilizing effect on inheritance of unstable pSC101 replicons (Tables 3 and 4). Importantly, the enhanced stabilization by excess DnaA or DnaB was not accompanied by enhanced plasmid DNA replication as measured by the copy number (Fig. 2), providing further evidence of the separateness of the partition and replication functions of these host proteins.

TABLE 3.

Effects of excess host replication proteins on stability of the par deletion pSC101 plasmid, pDLC6

| Plasmid(s) present in SC1148 | Stabilitya (% of cells containing pSC101 plasmid) after growth for:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| 20 generations | 40 generations | |

| pDLC6 (par) | 80 | 50 |

| pDLC6, pCM707 (DnaA, pBR322)b | 100 | 100 |

| pDLC6, pETDnaB (DnaB, pET)c | 100 | 100 |

| pDLC6, pMJRDnaB (DnaB, pBR322)d | 90 | 75 |

| pDLC6, pPL184 (DnaG, pBR322)e | 44 | ND |

| pDLC6, pETTau (tau subunit, pET) | 40 | ND |

Average from four experiments in which cells were grown without selection for the pSC101 plasmid but with selection for the plasmid expressing the host replication protein. Experiments were done at 37°C. ND, not determined.

The DnaA construct makes about five times the normal amount of DnaA protein (1).

pETDnaB makes about 10 times the normal amount of DnaB protein.

pMJRDnaB makes about four times the normal amount of DnaB protein.

pPL184 made about 10 times the normal amount of DnaG protein.

TABLE 4.

Reversal of the effect of excess RepA on the stability of wild-type pSC101 plasmid, pDLC8

| Plasmid(s) present in SC1148 | Stabilitya (% of cells containing pSC101 plasmid) after growth for:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| 20 generations | 40 generations | |

| pDLC8 | ND | 100 |

| pHI1249,b pDLC8 | 40 | 8 |

| pHI1249, pDLC8, pCM707 (DnaA) | 80 | 54 |

| pHI1249, pDLC8, pETDnaB (DnaB) | 100 | 100 |

| pHI1249, pDLC8, pPL184 (DnaG) | 40 | 6 |

| pHI1249, pDLC8, pETTau (Tau subunit of PolIII holoenzyme) | 40 | ND |

Average from four independent experiments. Cultures were grown without selection for the pSC101 derivative but with selection for the other plasmids. Experiments were done at 37°C. ND, not determined.

Produces 10 times the normal amount of RepA (20).

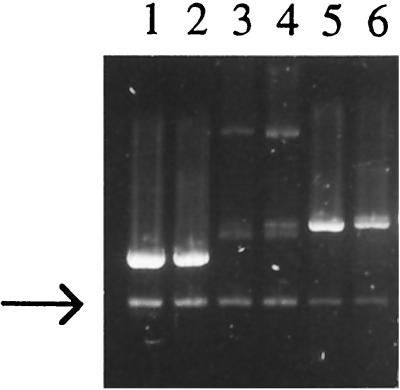

FIG. 2.

Lack of effect of excess DnaA or DnaB on amount of par deletion plasmid DNA. Cultures of PM191 with the par deletion pSC101 plasmid, pPM24, and another plasmid were grown with selection for both plasmids. Equal amounts of cells were harvested at an OD of 0.5, lysed rapidly, and run on an agarose gel (5). Lanes 1 and 2, pPM24 and pBR322; lanes 3 and 4, pPM24 and pCM707 (DnaA); lanes 5 and 6, pPM24 and pMJRDnaB. The arrow indicates the pPM24 plasmid DNA band; the pBR-based plasmid is the larger plasmid (higher band) in each lane. Densitometry tracing of the image indicated less pPM24 plasmid DNA in cells with excess DnaA (66%) or excess DnaB (44%) than in the cells with the pBR322 control.

Domain specificity of host proteins in the stabilization of pSC101.

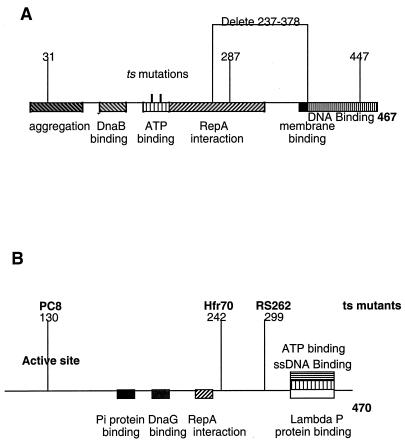

Overexpression of any of the dnaB(Ts) alleles described above, when cloned on pUC-based vectors, failed to stabilize par deletion pSC101 plasmids in wild-type hosts cultured at either 30°C (data not shown) or 37°C (Table 5), consistent with our evidence (Table 2) that dnaB mutant proteins fail to support normal plasmid partitioning. In contrast, some of the mutant DnaA proteins stabilized plasmid inheritance when overexpressed, as does the wild-type DnaA protein (20). DnaA protein mutated in the aggregation domain (A31T [43]), RepA binding domain (G287S [43]), DNA binding domain (L447W [43]), or DnaB binding domain (plasmid pACHA200 [42]) all stabilized partition-defective pSC101 plasmids when overexpressed in wild-type bacteria (Fig. 3A and Table 5). However, overexpression of a DnaA mutant protein containing an in-frame deletion (D237-378 [43]) that removes both the RepA binding domain and cell membrane binding domain failed to stabilize even though cells carrying this mutant allele can support replication of pSC101 (42) (Fig. 3A and Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Effects of overproduction of host mutant replication proteins on the stability of pSC101 par deletion plasmids

| Plasmid | pSC101 replicationa | Stabilityb (% of cells containing indicated pSC101 plasmid grown for 40 generations)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pWTT315 | pZC56 | pDLC6 | ||

| DNA overproducing | ||||

| pACYC184 | − | 40 | 28 | 20 |

| pACYCDnaA | + | 96 | 96 | 84 |

| pACDnaAA31T | ts | 72 | 80 | ND |

| pACHA200 | ts | 80 | 98 | ND |

| pACDnaAG287S | − | 98 | 96 | 82 |

| pACDnaAL447W | − | 100 | 100 | 96 |

| pACDnaAD237-378 | + | 0 | 2 | 24 |

| pACDnaA001-31c | 6 | 60 | ND | |

| DnaB overproducingd | ||||

| petDnaB | 100 | |||

| petDnaBts8 | 18 | |||

| petDnaBts70 | 16 | |||

| petDnaBts252 | 20 | |||

Taken from references 41 to 43; experiments done with cells without wild-type DnaA and with the mutant DnaA overexpressed.

The cultures were grown without selection for the par deletion pSC101 plasmid but with selection for the plasmid carrying the replication protein. Results are averages from two experiments using strain PM191; all experiments were done at 37°C.

Contains mutations R360E, R364E, and K372E.

For the DnaB-overproducing plasmids, experiments were also performed at 30°C with similar results.

FIG. 3.

The host replication genes DnaA and DnaB (marked to indicate functional domains) and the mutations used in this study. (A) Domains of DnaA (41). The mutant amino acid are indicated above the line; deletion D237-378 does not support oriC replication, while mutants 31, 287, and 477 do not support pSC101 replication. (B) Domains of DnaB and locations of the temperature-sensitive alleles (36).

As the above observations suggested a possible role for the membrane binding domain of DnaA (included in the deletion D237-378) in plasmid partitioning, we tested the effects on pSC101 stability of a DnaA protein containing mutations in amino acids specifically implicated in membrane binding (R360E, R364E, and K372E [16]). Hase et al. have shown that a DnaA protein containing these three mutations cannot interact with cardiolipin despite its normal ATPase activity (16). As seen in Table 5, overexpression of the mutant protein failed to stabilize partition-defective pSC101 replicons, thus localizing the DnaA region required for stabilization of pSC101 specifically to the membrane binding domain. Data showing the locations and properties of the DnaA mutants used in these experiments are summarized in Fig. 3A.

DISCUSSION

Plasmid pSC101 normally is stably maintained without selection in cultures of dividing cells. This stability is mediated by the plasmid par locus (28). In the presence of par, pSC101-based plasmids can be equipartitioned, even when their replication is shut off by loss of plasmid-encoded RepA function (45), implying that the partition and replication functions of RepA are distinct. The investigations reported here show that the E. coli replication proteins DnaA and DnaB also have effects on pSC101 plasmid partitioning and that these effects are separate from their functions in DNA replication.

Wild-type pSC101 plasmids were unstable in dnaB(Ts) mutant strains grown at a temperature permissive for DNA replication (30°C), whereas temperature-sensitive mutations in other essential DNA replication proteins (dnaA, dnaC, dnaG, and dnaN) failed to affect plasmid stability at any temperature where the proteins can function for bacterial DNA replication. At a temperature nonpermissive for plasmid or chromosomal DNA replication, the entire intracellular pool of pSC101 replicons segregated as a unit in the dnaB slow-stop mutant strain RS162 (dnaB252), while the plasmids were equipartitioned in the two other dnaB mutants (the fast-stop alleles in PC8 [dnaB8] and HfrH165 [dnaB70]) and in bacteria mutated in all other host replication genes tested. These results suggest a special role in plasmid partitioning for the region of the DnaB protein mutated in the dnaB252 strain. This region of the protein is conserved in DnaB homologues, but its function remains unknown. Interestingly, the two other dnaB alleles whose inactivation did not prevent equipartitioning show temperature-sensitive biochemical activities (in helicase, nucleotide binding, and primase activities) in in vitro assays, whereas the dnaB252 strain has wild-type DnaB activity in vitro at elevated temperatures (36).

The DnaB protein, when overproduced, can stabilize unstable pSC101 replicons, as was shown previously for DnaA (20); stabilization occurred without observable effects on plasmid copy number, consistent with earlier evidence that changes in pSC101 copy number are independent of stability (13, 45) and further supporting the notion that the effects of these host proteins on replication and partitioning are distinct. Both DnaA and DnaB have been shown to interact with each other as well as with the pSC101 RepA protein in vitro (24, 33). However, overproduction of other host replication proteins that also have been reported to interact with RepA, i.e., DnaG (25) and the tau subunit of PolIII holoenzyme (31), had no effect on pSC101 stability, implying that interaction with RepA per se is not the basis for the observed effects of DnaA and DnaB on plasmid partitioning.

It previously has been shown that chromosomal DNA replication and plasmid replication require different domains of the E. coli DnaA protein (24, 43). Overexpression of DnaA proteins in wild-type cells indicated that the DnaA region involved in pSC101 partitioning is different from the ones mediating its replication: DNA mutants that did not support replication of pSC101-stabilized par deletion pSC101 derivatives. Conversely, a DnaA allele (D237-378 [43]) that is mutated in the region of the DnaA protein that has been shown to interact with the bacterial membrane (15) supported pSC101 replication but failed to stabilize par deletion plasmids when overexpressed. Still other results that we obtained indicate that a DnaA variant containing multiple membrane binding domain mutations that eliminate the interaction of DnaA with cardiolipin (16) lost the ability to stabilize par deletion pSC101 plasmids when overexpressed, thus suggesting that the membrane binding domain of DnaA is the specific region of the protein required for partitioning of pSC101. Together, these findings establish that the replication and partition activities of DnaA on pSC101 are physically as well as functionally separated. Membrane binding by pSC101 plasmid molecules (39) has been observed to correlate with the stability of pSC101 plasmids (our unpublished data), raising the possibility that DnaA can serve as the bridge between the plasmid and host membrane during partition.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Hanne Ingmer for stimulating discussions; J. Kaguni, D. Bastia, D. Bramhill, N. Grindley, N. Dixon, R. Diaz, T. Mizushima, and M. Berlyn at CGSC for supplying plasmids and strains; D. Bramhill for the DnaB antibody; and K. Marians for the DnaG antibody.

This study was supported by NIH grants GM26355 and AI 08619 to S.N.C.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atlung T, Clausen E S, Hansen F G. Autoregulation of the dnaA gene of Escherichia coli K12. Mol Gen Genet. 1985;200:422–450. doi: 10.1007/BF00425729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker T A, Funnell B E, Kornberg A. Helicase action of dnaB protein during replication from the Escherichia coli chromosomal origin in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:6877–6885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beaucage S L, Miller C A, Cohen S N. Gyrase-dependent stabilization of pSC101 plasmid inheritance by transcriptionally active promoters. EMBO J. 1991;10:2583–2588. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07799.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biek D P, Cohen S N. Involvement of integration host factor (IHF) in maintenance of plasmid pSC101 in Escherichia coli: mutations in the topA gene allow pSC101 replication in the absence of IHF. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:2066–2074. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.4.2066-2074.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biek D P, Cohen S N. Propagation of pSC101 plasmids defective in binding of integration host factor. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:785–792. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.3.785-792.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolivar F, Rodriguez R L, Greene P J, Betlach M C, Heyneker H L, Boyer H W, Crosa J H, Falkow S. Construction and characterization of new cloning vehicles. II. A multipurpose cloning system. Gene. 1977;2:95–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonhoeffer F. DNA transfer and DNA synthesis during bacterial conjugation. Z Vererbungsl. 1966;98:141–148. doi: 10.1007/BF00897186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bramhill D, Kornberg A. A model for initiation at origins of DNA replication. Cell. 1988;54:915–918. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90102-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carl P L. Escherichia coli mutants with temperature-sensitive synthesis of DNA. Mol Gen Genet. 1970;109:107–122. doi: 10.1007/BF00269647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang A C Y, Cohen S N. Construction and characterization of amplifiable multicopy DNA cloning vehicles derived from the p15A cryptic miniplasmid. J Bacteriol. 1978;134:1141–1156. doi: 10.1128/jb.134.3.1141-1156.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen S N, Chang A C Y, Hsu L. Nonchromosomal antibiotic resistance in bacteria: genetic transformation of Escherichia coli by R-factor DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1972;69:2110–2114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.8.2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen S N, Miller C A. Non-chromosomal antibiotic resistance in bacteria. III. Isolation of the discrete transfer unit of R-factor R1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1970;67:510–516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.67.2.510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conley D L, Cohen S N. Isolation and characterization of plasmid mutations that enable partitioning of pSC101 replicons lacking the partition (par) locus. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1086–1089. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.4.1086-1089.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ely S, Wright A. Maintenance of plasmid pSC101 in Escherichia coli requires the host primase. J Bacteriol. 1985;164:484–486. doi: 10.1128/jb.164.1.484-486.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gardner J, Crooke E. Membrane regulation of the chromosomal replication activity of Escherichia coli DnaA requires a discrete site on the protein. EMBO J. 1996;15:2313–2321. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hase M, Yoshimi T, Ishikawa Y, Ohba A, Guo L, Mima S, Makise M, Yamaguchi Y, Tsuchiya T, Mizushima T. Site-directed mutational analysis for the membrane binding of DnaA protein. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:28651–28656. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.44.28651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hasunuma K, Sekiguchi M. Effect of dna mutations on the replication of plasmid pSC101 in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1979;137:1095–1099. doi: 10.1128/jb.137.3.1095-1099.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hasunuma K, Sekiguchi M. Replication of plasmid pSC101 in Escherichia coli K12: requirement for DnaA function. Mol Gen Genet. 1977;154:225–230. doi: 10.1007/BF00571277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holmes D S, Quigley M. A rapid boiling method for the preparation of bacterial plasmids. Anal Biochem. 1981;114:193–197. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90473-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ingmer H, Cohen S N. Excess intracellular concentration of the pSC101 RepA protein interferes with both plasmid DNA replication and partitioning. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7834–7841. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.24.7834-7841.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim S, Dallmann H G, McHenery C S, Marians K J. Coupling of a replicative polymerase and helicase: a tau-DnaB interaction mediates radip replication fork movement. Cell. 1996;84:643–650. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kornberg A, Baker T. DNA replication. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: W. H. Freeman & Co.; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 23.LeBowitz J H, McMacken R. The Escherichia coli DnaB replication protein is a DNA helicase. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:4738–4748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu Y-B, Datta H J, Bastia D. Mechanistic studies of initiator-initiator interaction and replication initiation. EMBO J. 1998;17:5192–5200. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.17.5192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu Y B, Ratnakar P V, Mohanty B K, Bastia D. Direct physical interaction between DnaG primase and DnaB helicase of Escherichia coli is necessary for optimal synthesis of primer RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12902–12907. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.12902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marszalek J, Zhang W, Hupp T R, Margulies C, Carr K M, Cherry S, Kaguni J M. Domains of DnaA protein involved in interaction with DnaB protein, and in unwinding the Escherichia coli chromosomal origin. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:18535–18542. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.31.18535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meacock P A, Cohen S N. Genetic analysis of the inter-relationship between plasmid replication and incompatibility. Mol Gen Genet. 1979;174:135–147. doi: 10.1007/BF00268351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meacock P A, Cohen S N. Partitioning of bacterial plasmids during cell division: a cis-acting locus that accomplishes stable plasmid inheritance. Cell. 1980;20:529–542. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90639-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller C A, Ingmer H, Cohen S N. Boundaries of the pSC101 minimal replicon are conditional. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4865–4871. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.17.4865-4871.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller C A, Beaucage S L, Cohen S N. Role of DNA superhelicity in partitioning of the pSC101 plasmid. Cell. 1990;62:127–133. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90246-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miron A, Patel I, Bastia D. Multiple pathways of copy control of gamma replicon of R6K: mechanisms both dependent on and independent of cooperativity of interaction of tau protein with DNA affect the copy number. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6438–6442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pardee A B, Jacob F, Monod J. The genetic control and cytoplasmic expression of “inducibility” in the synthesis of beta-galactosidase by E. coli. J Mol Biol. 1959;1:165–178. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ratnakar P V, Mohanty B K, Lobert M, Bastia D. The replication initiator protein pi of the plasmid R6K specifically interacts with the host-encoded helicase DnaB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5522–5526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruiz-Echevarria M J, Gimenez-Gallego G, Sabariegos-Jareno R, Diaz-Orejas R. Kid, a small protein of the parD stability system of plasmid R, is an inhibitor of DNA replication acting at the initiation of DNA synthesis. J Mol Biol. 1995;247:568–577. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sakakibara Y, Mizukami T. A temperature-sensitive Escherichia coli mutant defective in DNA replication: dnaN, a new gene adjacent to dnaA gene. Mol Gen Genet. 1980;178:541–553. doi: 10.1007/BF00337859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saluja D, Godson G N. Biochemical characterization of Escherichia coli temperature-sensitive dnaB mutants dnaB8, dnaB252, dnaB70, dnaB43, and dnaB454. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1104–1111. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.4.1104-1111.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sclafani R A, Weschler J A. Deoxyribonucleic acid initiation mutation dnaB252 is suppressed by elevated dnaC gene dosage. J Bacteriol. 1981;146:418–421. doi: 10.1128/jb.146.1.418-421.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Skogman G, Nilsson J, Gustaffson P. The use of a partition locus to increase stability of trytophan-operon-bearing plasmids in E. coli. Gene. 1983;23:105–115. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(83)90042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stamford N P J, Lilley P E, Dixon N E. Enriched sources of Escherichia coli replication proteins. The dnaG primase is a zinc metalloprotein. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1132:17–25. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(92)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sutton M D, Kaguni J M. The Escherichia coli dnaA gene: four functional domains. J Mol Biol. 1997;274:546–561. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sutton M D, Kaguni J M. Novel alleles of the Escherichia coli dnaA gene. J Mol Biol. 1997;271:693–703. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sutton M D, Kaguni J M. Novel alleles of the Escherichia coli dnaA gene are defective in replication of pSC101 but not oriC. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6657–6665. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.22.6657-6665.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tippe-Schindler R, Zahn G, Messer W. Control of the initiation of DNA replication in Escherichia coli. I. Negative control of initiation. Mol Gen Genet. 1979;168:185–195. doi: 10.1007/BF00431444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tucker W T, Miller C A, Cohen S N. Structural and functional analysis of the par region of the pSC101 plasmid. Cell. 1984;38:191–201. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90540-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wahle E, Lasken R S, Kornberg A. The dnaB-dnaC replication protein complex of Escherichia coli. I. Formation and properties. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:2463–2468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang M, Cohen S N. ard-1: a human gene that reverses the effects of temperature-sensitive and deletion mutations in the Escherichia coli rne gene and encodes an activity producing RNase E-like cleavages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10591–10595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wechsler J A, Gross J D. Escherichia coli mutants temperature-sensitive for DNA synthesis. Mol Gen Genet. 1971;113:273–284. doi: 10.1007/BF00339547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]