Abstract

A new insertion sequence (IS) of Mycoplasma fermentans is described. This element, designated IS1630, is 1,377 bp long and has 27-bp inverted repeats at the termini. A single open reading frame (ORF), predicted to encode a basic protein of either 366 or 387 amino acids (depending on the start codon utilized), occupies most of this compact element. The predicted translation product of this ORF has homology to transposases of the IS30 family of IS elements and is most closely related (27% identical amino acid residues) to the product of the prototype of the group, IS30. Multiple copies of IS1630 are present in the genomes of at least two M. fermentans strains. Characterization and comparison of nine copies of the element revealed that IS1630 exhibits unusual target site specificity and, upon insertion, duplicates target sequences in a manner unlike that of any other IS element. IS1630 was shown to have the striking ability to target and duplicate inverted repeats of variable length and sequence during transposition. IS30-type elements typically generate 2- or 3-bp target site duplications, whereas those created by IS1630 vary between 19 and 26 bp. With the exception of two recently reported IS4-type elements which have the ability to generate variable large duplications (B. B. Plikaytis, J. T. Crawford, and T. M. Shinnick, J. Bacteriol. 180:1037–1043, 1998; E. M. Vilei, J. Nicolet, and J. Frey, J. Bacteriol. 181:1319–1323, 1999), such large direct repeats had not been observed for other IS elements. Interestingly, the IS1630-generated duplications are all symmetrical inverted repeat sequences that are apparently derived from rho-independent transcription terminators of neighboring genes. Although the consensus target site for IS30 is almost palindromic, individual target sites possess considerably less inverted symmetry. In contrast, IS1630 appears to exhibit an increased stringency for inverted repeat recognition, since the majority of target sites had no mismatches in the inverted repeat sequences. In the course of this study, an additional copy of the previously identified insertion sequence ISMi1 was cloned. Analysis of the sequence of this element revealed that the transposase encoded by this element is more than 200 amino acid residues longer and is more closely related to the products of other IS3 family members than had previously been recognized. A potential site for programmed translational frameshifting in ISMi1 was also identified.

Insertion sequences (ISs) are a diverse group of small, mobile genetic elements that can insert into target DNA molecules with various degrees of site specificity. In prokaryotes, more than 500 such elements are now known (for a recent review, see Mahillon and Chandler [15]), and more examples of these intrinsically cryptic DNA segments continue to be identified as the output of known bacterial genomic sequences increases. Although IS elements are typically compact, encoding only functions that are necessary for transposition, they have long been recognized for their ability to influence gene expression, either by directly inactivating genes upon insertion or by providing promoters that increase the transcription of downstream genes (10). In addition, IS elements can effect chromosome rearrangements, including insertions, deletions, inversions, and duplications (17). Consequently, the mobility of such elements can have a profound impact on the stability of IS-containing genomic regions as well as influence the phenotype, or the antigen repertoire, of an organism.

Despite the considerable DNA sequence and functional diversity among ISs, comparisons of multiple elements have identified several characteristic features that are shared by most ISs. Most IS elements are between 800 and 2,500 bp long and contain two important structural components, a gene encoding a transposase and inverted repeat (IR) structures at the termini. Transposases are basic, DNA-binding proteins (typically 250 to 400 amino acids long) that target the terminal IR sequences during the transposition reaction. The IR sequences are usually 10 to 40 bp long, although a few IS elements that lack these terminal structures are known (15). During transposition of most IS elements, the two strands of the target DNA are asymmetrically cleaved, resulting in the generation of short direct repeats (DRs) of the target sequence (one abutting each terminus of the IS) at the conclusion of the insertion reaction (10). Although the extent of such target site duplication varies among elements (usually 2 to 14 bp), the length of the DR is generally fixed for each IS (15).

Based upon differences within the conserved features of IS elements, 17 IS families have been recognized on the basis of one or more of the following criteria: IS open reading frame (ORF) organization, conserved signature motifs among transposases, similarity of IR sequences, and length of target site duplications (15). Each family is named after the prototype member of the group. During the characterization of the Mycoplasma fermentans genomic region that encodes the potent MALP-2 immunomodulin, a previously unrecognized IS, designated IS1630, was identified (3). The putative IS1630 transposase has significant homology to IS30 transposase, but initial characterization of the insertion site and target site duplication suggested that IS1630 may have properties that not only distinguish it from the 15 characterized IS30 family members but also had not been observed for any IS element. Thus, the original cloned copy of IS1630 was flanked by 23-bp DRs, a duplication larger than any previously reported target site. Furthermore, the duplicated sequence was a perfect IR sequence that was derived from a candidate transcription terminator for the malp gene. In contrast, the IS30 prototype creates only 2-bp duplications, and although it exhibits a preference for insertion into sequences that contain a degree of dyad symmetry (18), there is not an absolute requirement for target sequences to conform to a perfect palindrome.

Prompted by the possibility that IS1630 may exhibit novel target site specificity and generate unusually long duplications of perfect IR sequences, we investigated the element further. This report describes the characterization of nine IS1630 copies from the genomes of two M. fermentans strains. Analyses of the flanking regions support our supposition that the processes of target site recognition and duplication by IS1630 are unlike those described for any other IS. In addition, a copy of the previously identified M. fermentans IS element ISMi1 (13) was cloned. This IS3 family member is unrelated to IS1630. Characterization of the reading frames within this copy of ISMi1 led to a reevaluation of the coding potential for this element and the proposal of a model for the translation of a functional transposase.

During the course of this study, two IS elements of the IS4 family, IS1634 in Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. mycoides (29) and IS1548 in Mycobacterium smegmatis (20), have been reported to generate large duplications of variable length, although neither element appears to have the target site recognition and duplication properties described here for the IS30 family member IS1630.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria, plasmids, and growth conditions.

M. fermentans PG18 (clone 39) and M. fermentans II-29/1 were propogated in Hayflick medium and GBF-3 medium respectively, as described previously (3). Escherichia coli DH10B (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.) and strains containing pZero2 or pZero2.1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) and its derivatives were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with 50 μg of kanamycin per ml.

DNA preparation and hybridization methods.

Genomic DNAs from M. fermentans PG18 and M. fermentans II-29/1 were prepared as described previously (3). For Southern hybridization, genomic DNA was digested to completion with either EcoRI or HindIII, resolved by electrophoresis in 0.7% (wt/vol) agarose gels, transferred to positively charged nylon membranes (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.), and hybridized with an oligonucleotide probe labeled at the 3′ end with digoxigenin (DIG) (primer 1, 5′ GAA GGA ACA TCA ATA TTA GGA TA). Hybridization and washing steps were carried out at 50°C with standard buffer solutions described in the guide provided by the membrane manufacturer (Boehringer). Hybridizing bands were detected by nonradioactive detection methods as described previously (31). Colony hybridization of transformants with DIG-labeled oligonucleotide primer 1 was carried out following the recommendations of the manufacturer of the nonradioactive labeling and detection system (Boehringer).

Cloning of IS1630 copies.

BglII-, HindIII-, or XbaI-digested chromosomal DNA from M. fermentans PG18 or BglII-digested total DNA from M. fermentans II-29/1 was ligated to BamHI-, HindIII-, or XbaI-digested cloning vector pZero 2 or pZero2.1 under conditions recommended by the vector supplier (Invitrogen). Following transformation into competent E. coli DH10B cells (Gibco BRL), kanamycin-resistant transformants were screened by standard colony hybridization methods with DIG-labeled oligonucleotide primer 1 (see above). Plasmid preparations (24) were analyzed for differently sized inserts that hybridized with probe 6 (5′ ATT AGG TTA TTC AAG AAC AAC TA). Plasmid clones containing individual IS1630 copies were generated by use of the following ligations: IS1630A (4-kb NheI fragment from strain PG18 in the XbaI site of pZero2.1); IS1630B, IS1630C, and IS1630D (BglII fragments from PG18 in the BamHI site of pZero2); IS1630E (XbaI fragment from PG18 in the XbaI site of pZero2); IS1630F (HindIII fragment from PG18 in the HindIII site of pZero2.1); and IS1630G, IS1630H, and IS1630I (BglII fragments from strain II-29/1 in pZero2).

DNA sequencing and computer analysis.

The nucleotide sequence for each of the cloned IS1630 copies was determined with six oligonucleotide primers that were located within the IS element. These were primer 1 (see above), primer 2 (5′ TAG TTG CTC AAA GTA AGT ATT CAA), primer 3 (5′ TGT AAG TTT ACA CCT AGA AAT TTG), primer 4 (5′ TAA TCC ATT ATC CTG AGT TAT AG), primer 5 (5′ CCA AAT ATT TTA GGG AGG GCT A), and primer 6 (see above). Flanking DNA sequences were determined with the outwardly facing primers 1 and 2, the cloning vector primers SP6 and M13F, and sequence-generated custom oligonucleotide primers. All oligonucleotides used in this study were synthesized on a model 3948 Nucleic Acid Synthesis and Purification System (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, Calif.), and all DNA sequencing was performed with Taq Dye terminators and a Prism 377 automated DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Inc.). Both of these services were carried out at the University of Missouri Molecular Biology Program DNA Core Facility. DNA and protein sequences were analyzed by use of the GCG software package (Genetics Computer Group, Madison, Wis.).

PCR amplification and chromosomal linkage analysis of M. fermentans strains.

Oligonucleotide primers 5 and 6 were used to amplify a 254-bp portion of IS1630 from M. fermentans genomic DNA preparations (kindly provided by S.-C. Lo, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, D.C.). These included DNAs from strains K7, MT-2, M39A, M70B, SK5, SK6, and Incognitus. The DNA template (10 ng) was used in a standard PCR consisting of 35 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, 50°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min. The resulting PCR amplicons were purified and analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

To determine whether chromosomal loci that were occupied by IS1630 in M. fermentans PG18 were occupied or “empty” in strain II-29/1 (and vice versa), opposing primer pairs were synthesized based on the sequences of the flanking genes and used for amplification with the Expand Long Template PCR System (Boehringer). The primer pairs used were A1 (5′ AAT TTA CCA CAC ATC ACC TGT T) and A2 (5′ GGT CGG GTT CAT ATA GTC CAA) for sequences flanking IS1630A, B1 (5′ GCA ACG GGT GGA ACA ACT AA) and B2 (5′ TTC GCC TCT CTT CTG CTC AA) for IS1630B, C1 (5′ TCC CTC GAA CGT TAG TTC GT) and C2 (5′ TAT GAG AAT AGG CGA CAA CTT T) for IS1630C, E1 (5′ GTC AAT GCT TGA ACC ACC TA) and E2 (5′ CAG GAA CAG GGA AAA GTG CTT) for IS1630E, and H1 (5′ GCA TTG AAC TAG TAT CTA CAT A) and H2 (5′ ATA CAC CAA GAA GCA CAA GAA A) for IS1630H. Reactions were carried out under the conditions recommended by the PCR system supplier (Boehringer) and with approximately 10 ng of DNA template. The thermocycle parameters consisted of 13 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, 57°C for 30 s, and 68°C for 3 min, followed by 20 cycles with the same parameters but with a 20-s extension to the elongation step in each cycle.

Inverse PCR methods.

Inverse PCR was used to isolate the DNA sequence downstream of IS1630B from M. fermentans PG18. Briefly, approximately 500 ng of genomic DNA was digested with HindIII, purified, and self-ligated by use of procedures described previously (3). Samples of the ligation were amplified with the Expand Long Template PCR System under conditions recommended by the product supplier. With primers B-inv1 (5′ CAT CAA TGC AAA ATT CAA GTG TG) and B-inv2 (5′ CTA AGG AAA CTA TTT CAA TAT CAT), a 3.5-kb fragment was generated; this size was expected based on prior Southern hybridization analysis with DIG-labeled primer B-inv1 as the probe. The resulting amplicon was purified and sequenced directly by primer walking.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in GenBank under accession no. AF100324 (IS1630A), AF179373 (IS1630B), AF179374 (IS1630C), AF179375 (IS1630D), AF179376 (IS1630E), AF179377 (IS1630F), AF179378 (IS1630G), AF179379 (IS1630H), and AF179380 (IS1630I).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Identification of an IS30-type IS element in M. fermentans.

During a comparison of the malp chromosomal regions of M. fermentans PG18 and II-29/1, a restriction fragment length polymorphism that was detected for several restriction enzymes proved to be due to the presence (in strain PG18) or absence of a previously unrecognized IS-like element (3). Designated IS1630 (by the Plasmid Reference Center, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, Calif.), this insertion element is 1,377 bp long and is bounded by 27-bp IRs (Fig. 1). IS1630 has an A+T content of 74%, which is close to the 72% A+T composition of the 15-kb genomic region within which this IS element was first identified. A single ORF encoding either 366 or 387 amino acid residues (depending on which of two candidate AUG start codons is used) occupies most of this compactly organized element. Analysis of the codon usage showed that 11 of the 14 Trp residues in the predicted product are encoded by UGA codons, indicating that this IS element is indigenous to mycoplasmas (16) and has not been transferred recently to M. fermentans from a nonmycoplasmal source.

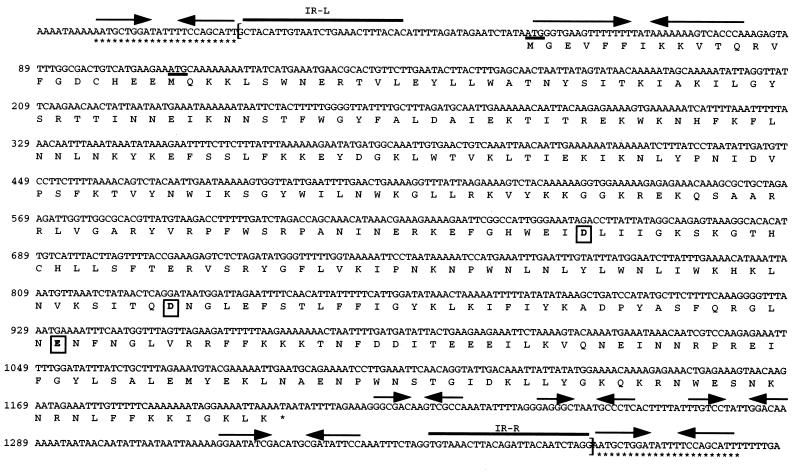

FIG. 1.

Nucleotide sequence and selected features of IS1630. The nucleotide sequence of IS1630A and flanking regions is shown, with the nucleotide numbers at left. Nucleotide 1 is the first nucleotide of the left IR of the IS. The deduced amino acid sequence encoded by the single ORF is shown in single-letter code below the DNA sequence, and each of the three acidic residues that comprise the highly conserved active-site motif (DDE) is enclosed within a box. The two candidate methionine start codons are underlined. The limits of IS1630 are indicated by square brackets, and the IR sequences at the left (IR-L) and right (IR-R) termini are highlighted by solid black lines. IR sequences within IS1630 are indicated by opposing arrows. The DR sequences that flank IS1630A are highlighted with asterisks below the corresponding sequence. The nucleotide sequence is presented in the orientation opposite that in GenBank AF100324.

Database searching revealed that the product of the single IS1630 ORF exhibited strong homology to transposases of the IS30 family of ISs, with the highest identity (27% over 349 amino acids) being shared with the transposase of IS30 from E. coli, the longest and prototypic member of this IS family (6, 15). Accordingly, it is proposed that IS1630 is the 16th member of the IS30 family. IS1630 extends the upper size limit for members of this group, being 160 bp longer than IS30. The IS1630 transposase has a pI of 10.8 (irrespective of the start codon used), which is within the range observed for other transposases (10) and which is compatible with the function of this protein in DNA binding. Despite the overall preponderance of basic amino acids, there are three critical acidic residues that have been shown to form a catalytic triad in several bacterial transposases and that can be identified by sequence analysis in many additional transposases. These three residues, known as the DDE motif, are conserved in the IS30 family (15), and comparison of the deduced consensus sequence of an extended DDE motif region for IS30-type transposases with that for IS1630 transposase revealed that these residues are similarly arranged in the primary sequence of the latter protein (Fig. 1). A search of the current databases revealed that IS1630 is the first IS30 family member to be reported from a mycoplasma species, although a distantly related transposase is encoded within the genome of the Spiroplasma citri bacteriophage phiSc1 (15, 23).

Despite the sequence conservation between IS1630 transposase and those encoded by other IS30-type elements and the possession of IR sequences of similar lengths, one feature of the single cloned IS1630 element was not typical of IS30 family members. A DR of 23 bp that had presumably been created by transposition-linked target site duplication flanked IS1630. Although the length of such duplications has not been determined for every IS30 family member, the length of known DRs for this family is restricted to 2 to 3 bp and, at the commencement of this study, the upper limit for any bacterial IS element was 14 bp (15). However, two recent publications reported the generation of unusually long DRs as a consequence of IS element insertion. Both IS1634 of M. mycoides (29) and IS1548 of M. smegmatis (20) can duplicate target sites that, in at least some instances, can exceed 200 bp. Neither of these elements is related to IS1630, as both IS1634 and IS1548 are IS4 family members. Taken together, these findings indicate that certain IS elements are able to duplicate larger DR sequences than was previously recognized and that this ability is neither restricted to members of one IS family nor widespread within any family.

It is formally possible that the 23-bp target site duplication associated with IS1630 insertion is due to a general consequence of transposition occurring in an M. fermentans genetic background, possibly due to the influence of additional host factors. In this regard, it should be noted that M. fermentans is known to harbor multiple copies of an IS-like element which belongs to the IS3 family (13) and is therefore unrelated to IS1630. This element, originally described by Hu and coworkers (13), has been referred to as the M. fermentans ISLE (19) but has recently been designated ISMi1 (15), reflecting the source of the original cloned copy (from M. fermentans Incognitus). Several copies of ISMi1 have been cloned and sequenced (4, 13, 19), and each copy is flanked by 3-bp DR sequences. Therefore, the large target site duplication flanking IS1630 is most probably due to the features of this IS element per se rather than being a more general phenomenon associated with transposition in M. fermentans.

IS1630 copy number in two M. fermentans strains.

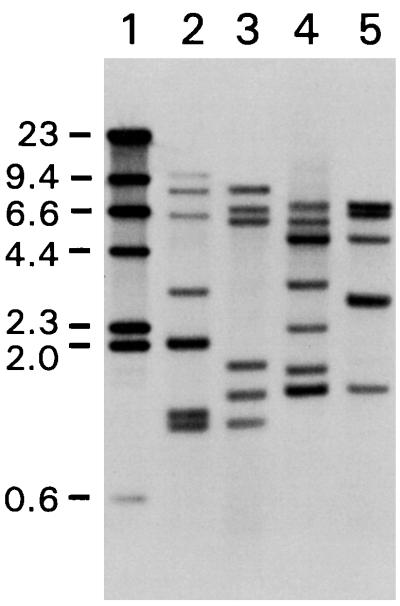

The data presented above suggested that IS1630 could generate large DR sequences upon transposition. To determine whether this function was a consistent feature of the element, multiple independent insertion events needed to be characterized. The absence of gene transfer methodology for M. fermentans and the presence of 11 UGA Trp codons in the transposase coding sequence prevented the application of standard genetic techniques for recovering multiple insertions in either mycoplasmas or E. coli, respectively. As an alternative, Southern analysis was used to determine whether multiple copies of IS1630 (and, therefore, IS1630 insertion sites) were present in the genomes of two M. fermentans strains. DNA from clonal isolates of strains PG18 and II-29/1 was restricted and subjected to Southern transfer and hybridization analysis with an IS1630-derived oligonucleotide as a probe. The oligonucleotide sequence was selected from a region of IS1630 which does not exhibit detectable homology to other IS elements. Under high-stringency hybridization and washing conditions, multiple hybridizing bands were observed in both restriction digests (EcoRI and HindIII) from each strain (Fig. 2). Both restriction digests of PG18 DNA yielded seven hybridizing bands, suggesting that there are at least seven copies of IS1630 in the genome of this strain. DNA from strain II-29/1 produced six hybridizing bands in the EcoRI digest and five in the HindIII reaction, although the intensity of hybridization of an approximately 3-kb HindIII fragment may indicate the presence of two hybridizing sequences in this band. Therefore, there are probably a minimum of six copies of IS1630 in strain II-29/1.

FIG. 2.

Identification of multiple copies of IS1630 in M. fermentans strains. Genomic DNA from M. fermentans PG18 (lanes 2 and 4) or II-29/1 (lanes 3 and 5) was digested with EcoRI (lanes 2 and 3) or HindIII (lanes 4 and 5), transferred to a nylon membrane, and hybridized with DIG-labeled oligonucleotide probe 5 (see Materials and Methods). Lane 1 contains DIG-labeled lambda HindIII markers (Boehringer), the sizes of which are indicated in kilobase pairs.

In addition to indicating that IS1630 was present in multiple copies in each strain, the hybridization patterns obtained for each strain suggested that some IS1630 copies were present in different locations in each genome. Indeed, from the analysis of the malp-associated restriction fragment length polymorphism, it was known that the occupancy of at least one insertion site (occupied by the copy of the element designated IS1630A) was strain variable (3).

Comparisons among individual IS1630 copies.

To characterize IS1630 and its associated DR sequences further, multiple copies were cloned in E. coli and identified by colony hybridization. In this way, five additional IS1630-containing fragments were cloned from strain PG18 and three were isolated from strain II-29/1. Sequence analysis of the nine cloned copies indicated that each was flanked by a unique nucleotide sequence, demonstrating that each clone contained an independent copy of the element together with its insertion site (Fig. 3). Each copy of IS1630 was given a specific designation based on its unique insertion site (IS1630A to IS1630F for those from strain PG18; IS1630G to IS1630I for those from strain II-29/1), with the original cloned copy having the IS1630A designation. With the exception of the truncated element, IS1630F, which contains only the 5′ 748 bp of the element, each of the other copies was similar in length to IS1630A.

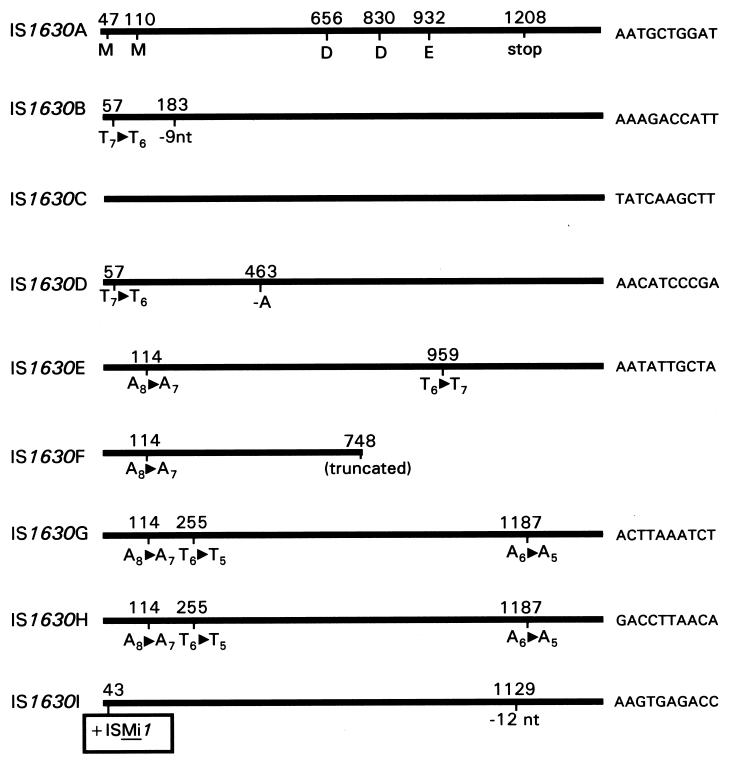

FIG. 3.

Location of indels within IS1630 variants. Each cloned copy of IS1630 is shown as a thick horizontal line. IS1630A and IS1630C lack nucleotide (nt) indels. The locations of indels within the other IS1630 variants are shown by a nucleotide number above the horizontal line (numbered according to the IS1630A sequence). The nature of the indel is shown below the line. The positions of two candidate methionine start codons (M), the stop codon (stop), and the residues that comprise the DDE motif are shown below the horizontal line representing IS1630A. The 10 nucleotides immediately downstream of each IS copy are shown at the right, except for the truncated IS1630F, which lacks the distal portion of IS1630.

Sequence comparisons among the IS1630 copies revealed sequence heterogeneity within the element, as had previously been reported for IS elements from other bacteria (15), including mycoplasmas (2, 32). Each of the six IS1630 copies from strain PG18 contained a distinct sequence. IS1630A and IS1630F were the most similar, with only three nucleotide differences (two substitutions and one single nucleotide deletion) in the 748 bp present in truncated IS1630F. The most dissimilar copies were IS1630D and IS1630E, which were 95.8% identical (52 substitutions and 4 single nucleotide insertions or deletions [indels]). In contrast, IS1630G and IS1630H (both from strain II-29/1) were identical, although they differed from IS1630I (also from strain II-29/1) and from the six copies from strain PG18. This result is particularly striking, since three 1-bp deletions are present in the identical copies, resulting in three frameshifts in the transposase coding sequence (Fig. 3). Therefore, it is improbable that a functional transposase is produced from either of these variants. Finding two copies of an apparently nonfunctional element inserted into different target sequences raises the possibility that functional copies of the element are able to mobilize defective copies in trans.

In addition to the frameshifts noted above for IS1630G and IS1630H, nucleotide indels were present in each of the IS1630 copies except for IS1630A (the prototype sequence) and IS1630C. Each of these sites was located within the larger of the two possible transposase coding sequences (Fig. 3). Most indels involved single nucleotides, although larger deletions of 9 bp (IS1630B) and 12 bp (IS1630I) were also detected. Interestingly, the majority of the single nucleotide indels occurred within short homopolymeric tracts of A's or T's, suggesting that they arose by slipped-strand mispairing during replication. Each of these indels resulted in a frameshift in the transposase coding sequence that was predicted to result in premature translation termination. Although programmed ribosomal frameshifting is a common mechanism for regulating the expression of transposase in IS3-type elements (15), such regulation has not been reported for any IS30 family member. Furthermore, when ribosomal frameshifting is used to regulate the level of transposase and therefore the frequency of transposition, it is restricted to a single specific frameshifting site. In contrast, the set of sequences reported here contain multiple indel sites, although the contracted homopolymeric tracts at nucleotides 67 and 121 are found in at least two distinct IS1630 variants. It should be noted that for at least two mycoplasma genes, alterations in the length of short mutation-prone tracts are used as a mechanism of phase variation that dictates whether a specific protein is translated or not. The P78 lipoprotein of M. fermentans is synthesized when the poly(A) tract contains 7 A's but is not translated when the coding sequence contains 8 A's (28). An analagous mutable poly(A) tract determines whether the Vaa adhesin of Mycoplasma hominis is translated (31). Whether changes in the length of homopolymeric tracts in IS1630 (by slipped-strand mispairing) are used as a mechanism to modulate the amount of functional transposase synthesized by a given copy of the element awaits further investigation.

In contrast to the short indels reported above, IS1630I is interrupted by an additional large insertion in the form of a complete copy of the 1.4-kb ISMi1. This IS3-type element is transposed into IS1630I at nucleotide 43, close to the left IR (Fig. 3).

Location of cloned copies of IS1630.

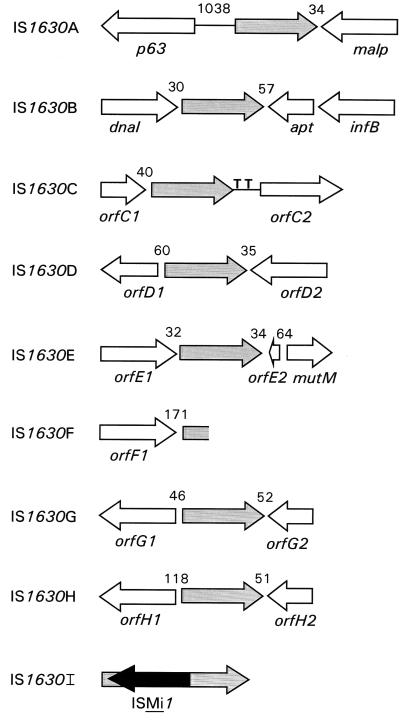

The nucleotide sequences that flank each of the cloned IS1630 copies were determined and compared to those in GenBank. The gene organization of these IS1630-linked regions is shown in Fig. 4, and the closest homologs of each gene product (as revealed by the FastA program) are presented in Table 1. Although approximately half of the gene products encoded by the flanking genes had recognizable homologs in the current database, eight of the gene products lacked identifiable counterparts from other bacterial genomes, including the fully sequenced chromosomes of Mycoplasma genitalium (8) and Mycoplasma pneumoniae (11). One striking feature resulting from this analysis of IS location is that in each case for which it was possible to determine location, IS1630 was inserted in an intergenic region close to a stop codon of a neighboring gene. It was not possible to readily determine the genes that flank IS1630I, as the clone harboring this copy of the element contains only a few nucleotides between the IR sequences and the restriction site used for cloning. As indicated above, IS1630I has a copy of ISMi1 inserted at nucleotide 43.

FIG. 4.

Gene organization of cloned IS1630 flanking regions. The location and direction of ORFs flanking each cloned IS1630 element are shown by open arrows. IS1630 is represented by a grey arrow (rectangle in the case of the truncated IS1630F), and ISMi1 is shown as a solid black arrow. The number of base pairs between the IS1630 termini and the adjacent ORFs is shown between the arrows. Two tRNA genes downstream of IS1630C are also shown (T). When an ORF could not be given an unambiguous gene assignment, even if it exhibited homology to genes of unknown function in other bacteria, a designation that indicated to which IS1630 copy the ORF was linked was given (e.g. orfG1 and orfG2 flank IS1630G).

TABLE 1.

Gene productsa encoded by genes flanking IS1630 in M. fermentans

| Gene product | Sizeb | Closest homolog | % Identity (length of the homologous regionc) | P | Comment | M. genitalium homologd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| InfB | >212 | InfB, Bacillus subtilis | 38 (176) | 2 × 10−30 | Translation initiation factor 2 | MG142 |

| Apt | 171 | Apt, Staphylococcus aureus | 51 (130) | 4 × 10−35 | Adenine phosporibosyltransferase | MG276 |

| DnaI | 297 | DnaI, B. subtilis | 26 (174) | 1 × 10−10 | Primosomal protein (DNA helicase) | ND |

| OrfC1 | 112 | ND | ND | |||

| OrfC2 | >38 | ND | Putative prolipoprotein signal sequence | ND | ||

| Leu-tRNA | 87 | Leu-tRNA, Helicobacter pylori | 93 (46) | 3 × 10−10 | UAA anticodon | tRNA-Leu1 |

| Lys-tRNA | 76 | Lys-tRNA, Mus musculus | 88 (71) | 3 × 10−13 | UUU anticodon | tRNA-Lys1 |

| OrfD1 | 248 | EpiF, S. aureus | 35 (199) | 5 × 10−23 | ATP-binding protein (ATP-binding cassette transporter) | MG179 |

| OrfD2 | 232 | ND | ND | |||

| OrfE1 | >373 | ORF, Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 26 (210) | 9 × 10−10 | Homolog is encoded by strand opposite that of assigned ORF Rv3294 | ND |

| OrfE2 | 48 | ND | Small Cys-rich protein (16 of 48 residues are Cys) | ND | ||

| MutM | 273 | Fpg, M. pneumoniae | 35 (275) | 1 × 10−43 | Foramidopyrimidine DNA glycosylase (DNA repair) | MG262.1 |

| OrfF1 | >230 | ND | ND | |||

| OrfG1 | 172 | ND | ND | |||

| OrfG2 | >151 | DNA polymerase I, B. subtilis | 43 (110) | 2 × 10−16 | Homology is in the exonuclease domain | MG262 |

| OrfHI | >322 | ND | ND | |||

| OrfH2 | >150 | ND | ND |

The relative position and orientation of each gene are indicated in Fig. 4.

Given in amino acid residues, except for tRNA products (nucleotides).

Given in amino acid residues, except for tRNAs (nucleotides).

From the M. genitalium database; designations are from a system described previously (8). ND, no homolog detected in databases (P, < 1 × 10−5).

IS1630 generates large target site duplications.

Members of the IS30 family of IS elements typically generate 2- or 3-bp duplications of the target site upon insertion (15, 18). The original IS1630 copy was flanked by a 23-bp DR, suggesting that IS1630 can create longer duplications. To determine whether or not this was a general rule for IS1630 insertion, the nucleotide sequences abutting the left and right IR sequences were analyzed for the six additional IS copies for which both flanking sequences were available. For five copies, perfect DRs ranging from 19 to 26 bp flanked the IS1630 element. The exception, IS1630D, lacked an apparent target site duplication (a possible reason for this finding is discussed below). These data are consistent with the hypothesis that IS1630 transposition creates large duplications but cannot rule out the formal possibility that IS1630 is inserted between tandem DRs.

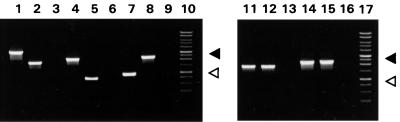

In the absence of a suitable experimental system to directly monitor insertion sites before and after transposition, a PCR approach was adopted to determine whether five sites occupied by IS1630 in one M. fermentans strain were empty in another, so that the sequences of unoccupied target sites could be determined. The results (Fig. 5) indicated that three of the five sites tested varied among strains in their occupancy. Thus, the sites occupied by IS1630A and IS1630B in strain PG18 are empty in strain II-29/1, and the IS1630H insertion site in strain II-29/1 is empty in strain PG18. The sequences of the three empty insertion sites were determined from the PCR products and compared to those of the corresponding occupied sites. This analysis showed that the DR sequences were present only when a target site was occupied, supporting the notion that they are created by target site duplication upon IS1630 insertion. As mentioned above, two recently identified IS4-type elements (20, 29) have also been shown to create DRs larger than the previously recognized range of 2 to 14 bp (15).

FIG. 5.

Determination of insertion site occupancy in two M. fermentans strains by PCR. Amplicons generated by PCR on genomic DNA from M. fermentans PG18 (lanes 1, 4, 7, 11, and 14) or II-29/1 (lanes 2, 5, 8, 12, and 15) or water-containing negative controls (lanes 3, 6, 9, 13, and 16) were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis. Each series of three reactions contained a pair of opposing oligonucleotide primers that were derived from sequences flanking a specific IS1630 copy: IS1630A (lanes 1 to 3), IS1630B (lanes 4 to 6), IS1630H (lanes 7 to 9), IS1630C (lanes 11 to 13), and IS1630E (lanes 14 to 16). For any primer pair, a size difference of 1.4 kb between strains indicates that a site is occupied in one strain and empty in the other. When a site is occupied in both strains, the resulting PCR products are equal in size. Lanes 10 and 17 contain a 1-kb ladder (Promega Corporation, Madison, Wis.). The positions of the 1-kb (open triangle) and 3-kb (solid triangle) size markers are indicated.

IS1630 is inserted into IR sequences that resemble transcription terminators.

Comparisons of the DR sequences failed to identify a well-conserved consensus sequence for target site recognition. However, each DR sequence is itself an IR sequence. Furthermore, the two different sequences that flank the termini of IS1630D and the sequence that flanks the single IS1630 terminal IR of IS1630F are also IR sequences. Therefore, IS1630 has apparent specificity for IR sequences. The finding that IS1630D is not flanked by long DR sequences but abuts two different IR sequences raises the possibility that IS1630D is a hybrid IS1630 element that has arisen by recombination between two similarly oriented IS elements that were each inserted into a unique IR. In this regard, it should be noted that the distal 150-bp portion of IS1630D is the most divergent from that present in IS1630A (11 nucleotide substitutions), whereas the proximal 1,200-bp portion of this element is the most similar to IS1630A (10 nucleotide substitutions). Such asymmetry in the distribution of nucleotide substitutions is not seen with any of the other IS1630 variants and is consistent with the notion that IS1630D arose by recombination between two IS elements.

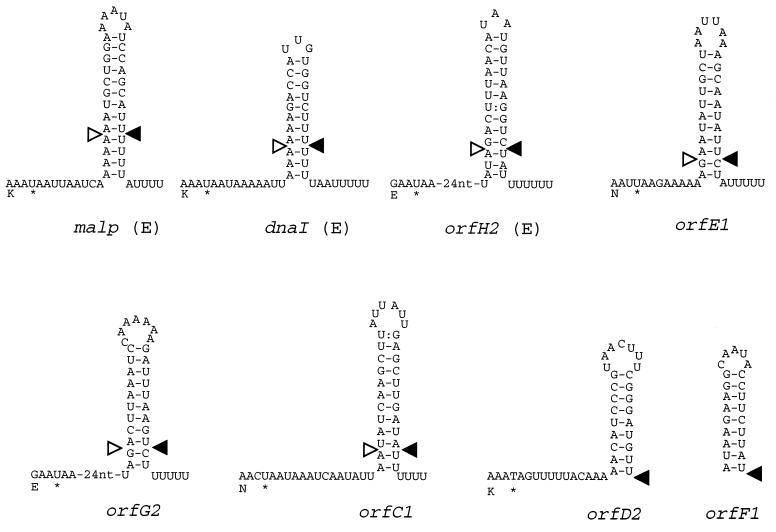

The observation that IS1630 targets IR sequences and the close proximity of IS1630 insertion sites to stop codons of neighboring genes suggested that the IR target sites may be rho-independent transcription terminators. Although transcription terminators have not been characterized in mycoplasmas, in other bacteria they are characterized by stem-loop structures that are followed by a short poly(U) tract in mRNAs. Analysis of the empty target sites for IS1630A, IS1630B, and IS1630H revealed that each site could encode a putative transcription terminator. In each case, a stem-loop preceding a poly(U) tract was located a short distance downstream of the translation termination codon (Fig. 6). The hypothetical empty sites for IS1630C, IS1630E, and IS1630G were extrapolated by deleting IS1630 and one of the DRs from each sequence. The resulting target sites also resembled transcription terminators. In the case of IS1630D, the sequence that was disrupted by IS element insertion cannot be deduced, but the presence of a stem-loop structure downstream of the orfD2 stop codon is consistent with this insertion site encoding a transcription terminator.

FIG. 6.

Features of IS1630 insertion sites. Predicted RNA secondary structures are shown for putative transcription terminators encoded by DNA sequences that are IS1630 target sites. The C-terminal amino acid (single-letter code: K, E or N) and stop codon (*) are shown at the left of each secondary structure. Three empty sites [(E)] were sequenced to confirm the stem-loop sequence. For orfE1, orfG2, and orfC1, the structures shown were derived by deleting the sequence of IS1630 and one copy of the DR. For orfD2 and orfF1, the appropriate IS1630 flanking sequences are not present to allow empty target sites to be deduced. The sites of insertion are shown by the solid triangles. The sequences duplicated as DRs are the DNA sequences that encode the stem-loop structures shown above the pairs of triangles. nt, nucleotides.

Based on sequence homology between transposases, IS30 is the element most closely related to IS1630. A detailed analysis of target sites for IS30 revealed that this element has a marked specificity for 24-bp sequences, conforming to a consensus sequence with a high degree of degeneracy (18). Interestingly, this consensus sequence was a nearly perfect palindrome. However, the individual insertion sites that were identified, although allowing the consensus sequence to be deduced, each had a large number of nonpalindromic residues. Even in two target sites that were identified as hot spots for IS30 insertion, only 10 of the 24 nucleotides conformed to a palindromic sequence. These results are in contrast to the target sites identified for IS1630, in which most of the DNA sequences that contribute to the stem structure of the putative terminators are perfect IRs (two structures have a single mismatch). Target site selection and duplication by IS1630 also differ from those exhibited by IS1397 of E. coli. Whereas IS1630 can insert into multiple IR sequences and generate long DRs, IS1397 inserts only into the central portion of one specific palindromic target, the highly conserved bacterial interspersed mosaic element (BIME) repeated sequence, and duplicates a 3- or 4-bp sequence (1).

Several interesting but unanswered questions regarding the mechanisms of target choice and duplication are raised by these findings. In the absence of any obvious consensus for length or sequence within the IRs that have been selected as targets, it is not known how such sequences would be recognized by IS1630. Also, the complete IR is not duplicated in any instance, and since the length of the duplication is variable, it is not apparent what dictates the length of the duplication. In each case, a symmetrical portion of the IR is duplicated, even though the length of the repeat varies between insertion sites and can be either an odd or an even number of base pairs. It is not known how this symmetry is maintained. It would be of considerable interest to determine whether multiple independent insertions into a single target all generate the same duplication.

It is not known whether the target sequences are recognized as double-stranded DNA or as an alternative DNA configuration. It would be of interest to determine whether the target sequences are recognized as extruded cruciform structures or as stem-loop structures in single-stranded DNA regions that may exist transiently during replication. In such scenarios, recognition and symmetrical duplication may be determined by features of DNA secondary structure rather than by determinants encoded within the primary nucleotide sequence.

IS1630 is widely distributed among M. fermentans isolates.

To address the strain distribution of IS1630 further, primers 5 and 6 were used in PCR to amplify a 254-bp region of the IS. Amplicons of the expected sizes were obtained for each of the seven M. fermentans isolates tested (data not shown). These included MT-2, SK5, SK6, Incognitus, K7, M39A, and M70B. The cloning of IS1630 variants from strains PG18 and II-29/1 raises the number of IS1630-containing M. fermentans strains to nine. The wide distribution of IS1630 among M. fermentans strains suggests that sequences within IS1630 are potentially useful diagnostic tools for the PCR-based detection of the human infectious agent M. fermentans. IS1630 is not present in the complete genome sequences of M. genitalium (8) and M. pneumoniae (11), but its possible presence in numerous other human mycoplasmas, both pathogens and commensals, requires determination.

Further analysis of ISMi1 from M. fermentans II-29/1.

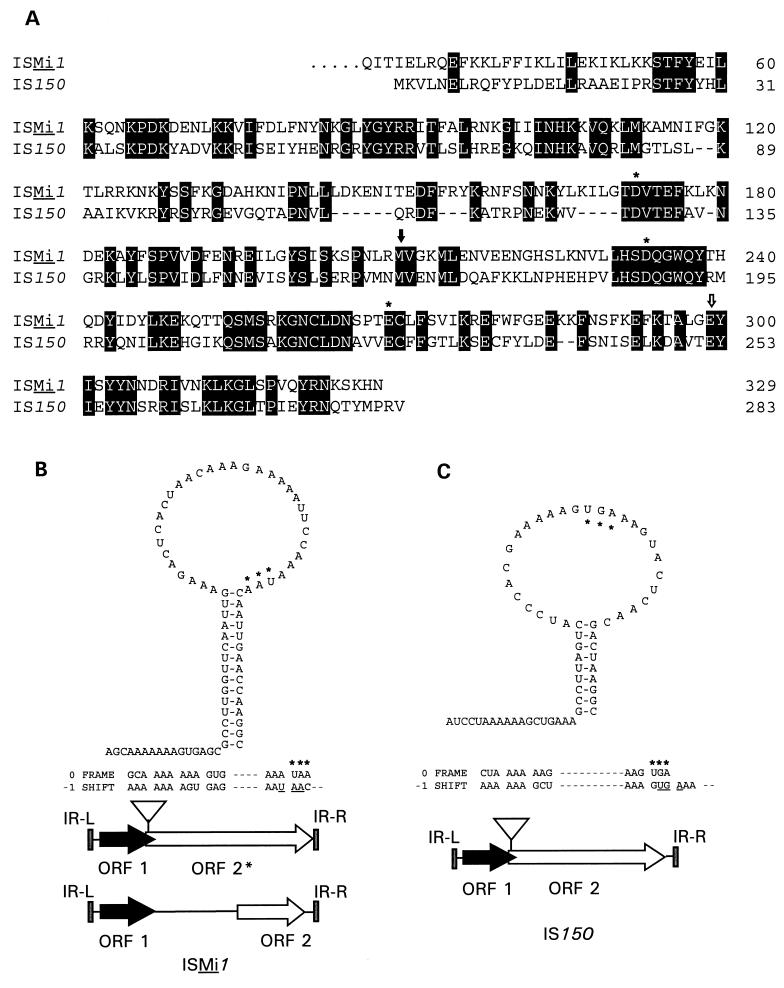

As reported above, IS1630I from M. fermentans II-29/1 contains a copy of the IS3-type element ISMi1. Although the sequence of this ISMi1 copy is >98% identical to that described for the original IS (13), the sequence differences warranted a reevaluation of the coding potential of this element. The sequence of the original copy contained two potential ORFs separated by a 541-bp untranslated sequence. The two ORFs, designated ORF1 and ORF2, encoded 143 amino acid residues and 109 amino acid residues, respectively. The ORF2 product had a short region (57 amino acid residues) of homology to transposases of the IS3 group (13).

The sequence of the ISMi1 element that was inserted into IS1630I contains five single nucleotide indels which change the size and sequence of ORF2. Three indels upstream of the originally proposed ORF2 result in an approximately 200-amino-acid extension of the N terminus encoded by ORF2 such that ORF1 and the longer ORF2 overlap (Fig. 7B). In addition, two single nucleotide insertions in the 3′ coding sequence cause the C-terminal 13 amino acids encoded by ORF2 to be replaced by 26 amino acids from alternative reading frames. This alternate ORF2, designated ORF2*, is also present in two cloned DNA fragments from M. fermentans PG18 that contain ISMi1 sequences (4). The five indels that create ORF2* were also present in the recently reported ISMi1 sequences from M. fermentans M106 and KL-4 (19). Therefore, the five indels identified in this report are present in five of the seven known ISMi1 sequences and should therefore be considered part of the consensus sequence of this element. The authenticity of ORF2* is also supported by the extensive homology between ORF2* and ORF2 of IS150 (and other IS3 family members). The homology extends throughout most of the N-terminal extension encoded by ORF2* and continues into the 26-amino-acid C terminus that is not encoded by ORF2 (Fig. 7A). Furthermore, the first aspartic acid residue of the DDE motif, the critical catalytic triad of acidic amino acid residues in many bacterial transposases, is present only in the ORF2* product.

FIG. 7.

Features of ISMi1. (A) Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequences encoded by ORF2* from the copy of ISMi1 inserted into IS1630I and ORF2 from IS150. Identical amino acid residues are highlighted with a black background. The numbers at the right indicate the positions of the amino acid residues for the respective ORFs (residue 1 for ORF2* is the first amino acid for the −1 reading frame after the stop codon for ORF1). A black vertical arrow indicates the originally proposed (13) position of the methionine start site for ORF2, and an open vertical arrow indicates the start site for the C-terminal region encoded by ORF2*, which is absent in ORF2. The residues comprising the DDE motif are indicated by asterisks. Gaps in the alignment are shown by dashes. (B) Proposed model for a putative frameshifting window in ISMi1 and comparison of the revised (upper cartoon) and originally proposed (lower cartoon) ORF arrangements in this element. A stem-loop structure for the ISMi1 mRNA region in which ribosomal frameshifting is proposed to occur is shown, together with the 0 and −1 reading frames. The ORF1 stop codon (UAA) is highlighted with asterisks in the secondary structure model and in the 0-frame sequence. The same three nucleotides are underlined in the −1 reading frame, in which they are components encoding consecutive Asn codons. In the schematic diagram showing the features of ISMi1, ORF1 is shown as a black arrow and ORF2 and ORF2* are represented by open arrows. The left (IR-L) and right (IR-R) IRs are shown as grey vertical bars at the IS termini. The location of the proposed frameshifting window is indicated by a triangle. The horizontal lines indicate untranslated regions. (C) Features of the frameshift window that has been established for IS150, highlighted as in panel B. The ORF1 stop codon in this case is a UGA codon. The features of IS150 are shown in the schematic diagram, following the conventions used in panel B.

A general property of most IS elements of the IS3 family is the use of programmed ribosomal frameshifting to synthesize a transframe product that fuses ORF1 and ORF2 (15). This mechanism has been well established for IS150 (30), IS3 (26), and IS911 (21) and is proposed to regulate the amount of active transposase that is translated. Programmed frameshifting in the case of IS150 depends upon the following features: ORF1 and ORF2 partially overlap and are in the 0 and −1 registers, respectively; a “slippery” codon region is present within this frameshifting window (in the case of IS150, the sequence is A6G, but A7 can be used in other systems); and a stem-loop structure containing the ORF1 stop codon is present a few nucleotides downstream of the slippery codon region (Fig. 7C). In ISMi1, ORF2* lacks a recognizable start codon but partially overlaps ORF1, suggesting that translational frameshifting may occur in this IS3 family member also. Inspection of the DNA sequence within which such a frameshift must occur (83 nucleotides) revealed that the primary sequence and secondary structure requirements necessary for frameshifting in IS150 have candidate counterparts in ISMi1. The overlapping ORF1 and ORF2 are in the appropriate frame registers to accommodate a −1 shift, and a large stem-loop structure that contains the ORF1 stop codon is predicted to form within the frameshifting window and to be located a few nucleotides downstream of a possible slippery sequence (Fig. 7B and C). There is insufficient data regarding the concentration of individual tRNA species and codon usage to determine what constitutes a slippery codon region in M. fermentans, but the candidate sequence A7G contains both an A7 component and an A6G component, both of which are known to support frameshifting in other programmed systems. Taken together, these observations suggest that ISMi1 is more closely related to IS150 and other IS3 family members than had previously been recognized.

Concluding remarks.

Prior to this study, the sequences and features of five IS elements from mycoplasmas had been reported. Four of these, IS1138 of Mycoplasma pulmonis (2), IS1221 of Mycoplasma hyorhinis and Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae (32), IS1296 of M. mycoides (9), and ISMi1 (also known as ISLE) of M. fermentans (13), are members of the IS3 family, the largest of the 17 major groupings of IS elements that were recently reviewed (15). The only non-IS3 family IS elements to be described so far in mycoplasmas are the IS4-type element IS1634 of M. mycoides (29) and the IS30 family member IS1630, described in this report. Although IS1630 possesses a putative transposase with hallmark signature sequence motifs for the group and has overall similarity in organization to other IS30 members, IS1630 has expanded the spectrum of insertion site specificity and the extent of target site duplication. Three IS elements that create long DRs have now been described, and while those that have been identified so far for IS1630 are shorter than those for the IS4-type elements, the symmetry of the IRs within the duplication has not been observed previously.

The consequences of IS1630 insertion for transcription termination of the targeted gene await further investigation. In all cases, insertion separates the poly(U) tract from the stem-loop structure of the putative terminator. Neither terminus of IS1630 provides a compensating poly(U) tract, and as a result, the efficiency of transcription termination may be reduced. In the case of IS1630B, IS1630C, and IS1630E, the transposase gene is in the same orientation as the upstream gene. In these examples, disruption of the terminator could lead to increased transcription of transposase mRNA. However, IS elements usually have mechanisms to tightly regulate the amount of transposase that is synthesized (15), so it will be of interest to determine whether IS1630 has specific sequences that protect against transcriptional readthrough from disrupted terminators.

Mycoplasmas are believed to have arisen via reductive evolution, resulting in bacteria with limited metabolic capabilities and small genome sizes (7, 22). Despite this reduction in coding sequences, a growing number of accessory genetic elements are being identified for these bacteria. IS1630 is the second IS element to be described for M. fermentans, following the identification of ISMi1 by Hu and coworkers (13). There is considerable variation between isolates of this species, in terms of both genome size (5, 25) and antigen repertoire (27). The presence of multiple copies of at least two mobile genetic elements may contribute to both of these variable features. A recent report has noted the ability of ISMi1 to bring about chromosome rearrangements (12). IS1630 may have also caused deletions, since the recombination event postulated to generate IS1630D would have deleted intervening sequences between two IS1630 copies.

The target site specificity and duplications associated with IS1630 are unlike those described for any other IS element. Why such specificity arose is not known, but it will be of interest to determine whether IS30-type elements with similar properties exist in other mycoplasma species. The targeting of transcription terminators may be considered a protective mechanism to ensure that a limited, minimal gene complement is not further diminished by insertional inactivation. However, this possibility should be balanced against the possibility of IS1630 inserting into one of the large number of IR sequences present within rRNA and tRNA genes. In the case of rRNA genes, two copies exist for each rRNA species (14), so insertion into one copy may not be a lethal event. However, mycoplasmas, in general, possess only a single gene for each tRNA, and so disruption by IS1630 would be lethal. It will be of interest to determine whether all IR sequences are possible targets for IS1630 or whether those present in critical rRNA genes are not recognized as insertion sites.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Shyh-Ching Lo for providing DNA preparations from M. fermentans isolates.

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grant AI32219 (to K.S.W.) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and by a University of Missouri Molecular Biology Program predoctoral fellowship (to J.L.L.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bachellier S, Clément J M, Hofnung M, Gilson E. Bacterial interspersed mosaic elements (BIMEs) are a major source of sequence polymorphism in Escherichia coli intergenic regions including specific associations with a new insertion sequence. Genetics. 1997;145:551–562. doi: 10.1093/genetics/145.3.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhugra B, Dybvig K. Identification and characterization of IS1138, a transposable element from Mycoplasma pulmonis that belongs to the IS3 family. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:577–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calcutt M J, Kim M F, Karpas A B, Mühlradt P F, Wise K S. Differential posttranslational processing confers intraspecies variation of a major surface lipoprotein and a macrophage-activating lipopeptide of Mycoplasma fermentans. Infect Immun. 1999;67:760–771. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.2.760-771.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calcutt, M. J., M. S. Lewis, and K. S. Wise. 1999. Unpublished data.

- 5.Campo L, Larocque P, La Malfa T, Blackburn W D, Watson H L. Genotypic and phenotypic analysis of Mycoplasma fermentans strains isolated from different host tissues. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1371–1377. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.5.1371-1377.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caspers P, Dalrymple B, Iida S, Arber W. IS30, a new insertion sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Mol Gen Genet. 1984;196:68–73. doi: 10.1007/BF00334094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dybvig K, Voelker L L. Molecular biology of mycoplasmas. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1996;50:25–57. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fraser C M, Gocayne J D, White O, Adams M D, Clayton R A, Fleischmann R D, Bult C J, Kerlavage A R, Sutton G, Kelley J M, Fritchman J L, Weidman J F, Small K V, Sandusky M, Fuhrmann J, Nguyen D, Utterback T R, Saudek D M, Phillips C A, Merrick J M, Tomb J F, Dougherty B A, Bott K F, Hu P C, Lucier T S, Peterson S N, Smith H O, Hutchison III C A, Venter J C. The minimal gene complement of Mycoplasma genitalium. Science. 1995;270:397–403. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frey J, Cheng X, Kuhnert P, Nicolet J. Identification and characterization of IS1296 in Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. mycoides SC and presence in related mycoplasmas. Gene. 1995;160:95–100. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00195-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galas D J, Chandler M. Bacterial insertion sequences. In: Berg D E, Howe M M, editors. Mobile DNA. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1989. pp. 109–162. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Himmelreich R, Hilbert H, Plagens H, Pirkl E, Li B-C, Herrmann R. Complete sequence analysis of the genome of the bacterium Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4420–4449. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.22.4420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu W S, Hayes M M, Wang R Y H, Shih J W K, Lo S C. High-frequency DNA rearrangements in the chromosomes of clinically isolated Mycoplasma fermentans. Curr Microbiol. 1998;37:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s002849900327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu W S, Wang R Y, Liou R S, Shih J W, Lo S C. Identification of an insertion-sequence-like genetic element in the newly recognized human pathogen Mycoplasma incognitus. Gene. 1990;93:67–72. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90137-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang Y, Robertson J A, Stemke G W. An unusual rRNA gene organization in Mycoplasma fermentans (incognitus strain) Can J Microbiol. 1995;41:424–427. doi: 10.1139/m95-056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahillon J, Chandler M. Insertion sequences. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:725–774. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.3.725-774.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muto A, Andachi Y, Yamao F, Tanaka R, Osawa S. Transcription and translation. In: Maniloff J, McElhaney R N, Finch L R, Baseman J B, editors. Mycoplasmas: molecular biology and pathogenesis. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1992. pp. 331–347. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohtsubo E, Sekine Y. Bacterial insertion sequences. In: Saedler H, Gierl A, editors. Transposable elements. New York, N.Y: Springer-Verlag; 1996. pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olasz F, Kiss J, König P, Buzás S R, Arber W. Target specificity of insertion element IS30. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:691–704. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pitcher D, Hilbocus J. Variability in the distribution and composition of insertion sequence-like elements in strains of Mycoplasma fermentans. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;160:101–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb12898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plikaytis B B, Crawford J T, Shinnick T M. IS1549 from Mycobacterium smegmatis forms long direct repeats upon insertion. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1037–1043. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.5.1037-1043.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Polard P, Prère M F, Chandler M, Fayet O. Programmed translational frameshifting and initiation at an AUU codon in gene expression of bacterial insertion sequence IS911. J Mol Biol. 1991;222:465–477. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90490-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Razin S, Yogev D, Naot Y. Molecular biology and pathogenicity of mycoplasmas. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1094–1156. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1094-1156.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Renaudin J, Aullo P, Vignault J C, Bové J-M. Complete nucleotide sequence of the genome of Spiroplasma citri virus SpV1-R8A2 B. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:1293. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.5.1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schaeverbeke T, Cleric M, Lequen L, Charron A, Bébéar C, De Barbeyrac B, Bannwarth B, Dehais J. Genotypic characterization of seven strains of Mycoplasma fermentans isolated from synovial fluids of patients with arthritis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1226–1231. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.5.1226-1231.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sekine Y, Eisaki N, Ohtsubo E. Translational control in production of transposase and in transposition of insertion sequence IS3. J Mol Biol. 1994;235:1406–1420. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Städtlander C T K H, Zuhua C, Watson H L, Cassell G H. Protein and antigen heterogeneity among strains of Mycoplasma fermentans. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3319–3322. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.9.3319-3322.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Theiss P, Wise K S. Localized frameshift mutation generates selective, high-frequency phase variation in a surface lipoprotein encoded by a mycoplasma ABC transporter operon. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4013–4022. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.12.4013-4022.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vilei E M, Nicolet J, Frey J. IS1634, a novel insertion element creating long, variable-length direct repeats which is specific for Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. mycoides small-colony type. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1319–1323. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.4.1319-1323.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vögele K, Schwartz E, Welz C, Schiltz E, Rak B. High-level ribosomal frameshifting directs the synthesis of IS150 gene products. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:4377–4385. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.16.4377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang Q, Wise K S. Localized reversible frameshift mutation in an adhesin gene confers a phase-variable adherence phenotype in mycoplasma. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:859–869. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1997.mmi509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zheng J, McIntosh M A. Characterization of IS1221 from Mycoplasma hyorhinis: expression of its putative transposase in Escherichia coli incorporates a ribosomal frameshift mechanism. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:669–685. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]