Abstract

Objective

To explore the causes and levels of moral distress experienced by clinicians caring for the low-income patients of safety net practices in the USA during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Design

Cross-sectional survey in late 2020, employing quantitative and qualitative analyses.

Setting

Safety net practices in 20 US states.

Participants

2073 survey respondents (45.8% response rate) in primary care, dental and behavioural health disciplines working in safety net practices and participating in state and national education loan repayment programmes.

Measures

Ordinally scaled degree of moral distress experienced during the pandemic, and open-ended response descriptions of issues that caused most moral distress.

Results

Weighted to reflect all surveyed clinicians, 28.4% reported no moral distress related to work during the pandemic, 44.8% reported ‘mild’ or ‘uncomfortable’ levels and 26.8% characterised their moral distress as ‘distressing’, ‘intense’ or ‘worst possible’. The most frequently described types of morally distressing issues encountered were patients not being able to receive the best or needed care, and patients and staff risking infection in the office. Abuse of clinic staff, suffering of patients, suffering of staff and inequities for patients were also morally distressing, as were politics, inequities and injustices within the community. Clinicians who reported instances of inequities for patients and communities and the abuse of staff were more likely to report higher levels of moral distress.

Conclusions

During the pandemic’s first 9 months, moral distress was common among these clinicians working in US safety net practices. But for only one-quarter was this significantly distressing. As reported for hospital-based clinicians during the pandemic, this study’s clinicians in safety net practices were often morally distressed by being unable to provide optimal care to patients. New to the literature is clinicians’ moral distress from witnessing inequities and other injustices for their patients and communities.

Keywords: Human resource management, MEDICAL ETHICS, PRIMARY CARE, QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study’s clinician study cohort is large and broad in terms of its disciplines, types of safety net practice work settings and states across the USA, and its subject participation rate is strong.

This study presents office-based clinicians with a broad definition of moral distress and non-constrained measurement tool, the Moral Distress Thermometer, which do not limit findings to what has been learnt previously in studies of clinicians working in hospital settings.

Clinicians’ understanding of the single-question Moral Distress Thermometer and some other aspects of its validity were not assessed.

Relying on open response survey item data to learn about causes of moral distress did not allow us to clarify clinicians’ responses or more fully understand what the issues they reported mean to them.

We cannot directly know how moral distress changed for US outpatient safety net clinicians with the pandemic because there are no studies prior to the pandemic.

Introduction

News photos and stories of physicians and nurses labouring in intensive care units overflowing with ill and frightened patients have been among the most iconic images of the COVID-19 pandemic.1 2 These clinicians have been shown to be physically and emotionally exhausted, and also said to be morally distressed by witnessing and participating in people’s illness, care and death in sheer numbers and under circumstances that feel morally wrong.3–6 The concept of moral distress among healthcare professionals is several decades old but still evolving.7–11 In this study, we conceptualise moral distress as the psychological unease or distress that occurs when one witnesses, does things or fails to do things that contradict deeply held moral and ethical beliefs and expectations.

Likely, clinicians in many disciplines and work settings have felt morally distressed in their work during the pandemic.5 12 This has been demonstrated for broad cohorts of principally hospital-based clinicians in the USA, UK and worldwide.10 13–15 We are aware of no studies that have assessed moral distress during the pandemic specifically among outpatient clinicians, but such distress is easy to imagine. Outpatient offices in the USA were commonly closed early in the pandemic and then reopened but operated with restricted services and altered care standards to promote safety for more than a year, and these changes may have made outpatient clinicians feel that they were violating their core moral duties to patients of beneficence and non-maleficence, that is, to help patients to the best of their ability and not cause them harm.16–22 Clinicians could have been morally distressed by the many patients who, out of fear of being infected by coming to their health provider’s office, delayed or forewent needed office visits and care, including for heart attacks and cancer treatment.20 23–25 Further, for the many months when adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) was unavailable for healthcare providers in the USA and vaccines not yet available to provide protection, many clinicians in both outpatient and inpatient settings could have felt that they had violated their duty to themselves simply by continuing to see patients and thereby risking becoming infected, and then infecting their families.12–14 26–28 Moral distress during the pandemic can have important consequences for clinicians, as moral distress is associated with disengagement from patients, compassion fatigue and poorer quality of care,29 30 poorer clinician mental health and burnout,13 29 31–33 and job dissatisfaction and turnover.29 32 34

Among outpatient clinicians in the USA, those in safety net practices, which provide care to poor and often racial-ethnic minority patients who face barriers to receiving care in the US mainstream healthcare system, have worked with patients most affected by illness and death during the pandemic.35–40 This patchwork of publicly funded or subsidised practices—Federally Qualified Health Centers, clinics of the Indian Health Service, county health departments, community mental health facilities and others—frequently have not had the financial resources to adapt care to continue safely providing services to their patients.41–43 Moral distress during the pandemic for clinicians in these special settings therefore may have been greater than for outpatient clinicians generally.

This study assesses moral distress at 9 months into the COVID-19 pandemic among clinicians working in a wide range of types of safety net practices in 20 US states. With no available listing of safety net practices of the many types across states or rosters of their clinicians, we study moral distress within a large subgroup of safety net clinicians for whom complete roster data are uniquely available. Specifically, we study clinicians participating in federal and state loan repayment (LRP) and related programmes that help clinicians pay down debt incurred from the costs of their training in exchange for a period of work within safety net practices.44–46 This study assesses these clinicians’ self-reported levels of moral distress. It categorises and describes the issues they report caused them most moral distress during the pandemic. It also compares the moral distress levels and issues of primary care, dental and behavioural health clinicians, whose care required different adaptations to the pandemic bringing varying challenges to clinicians and patients.47 It further assesses how the level of moral distress clinicians report varies with the types of issues they report caused them most distress.

Methods

Subjects

To study the pandemic’s various effects on clinicians working in safety net practices, we surveyed all primary care, dental and behavioural health clinicians and providers in 20 US states who were participating in the education loan repayment and scholarship programmes of the National Health Service Corps (NHSC) and in states’ similar programmes that have service commitments to work within safety net practices.45 46 48 49 The 20 states (Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Delaware, Iowa, Kentucky, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, North Carolina, North Dakota, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Virginia and Wyoming) constitute 40% of all US states, and do not differ statistically from the 30 other US states in both mean and median total population, mean per capita income, percentage population living in urban versus rural areas and number of known positive COVID-19 infections as of 15 December 2020, during the survey period.50–52 These 20 states participate in the Provider Retention Information System Management Collaborative (one member state at the time declined participation), a voluntary cooperative of states’ clinician workforce programme offices and offices of rural health that annually surveys clinicians serving in LRP and scholarship programmes to assess programme outcomes.53 54

The US Bureau of Health Workforce regularly provides the Collaborative with roster information on all clinicians participating in the federal NHSC, and the Collaborative’s lead agency for each state provides information on all participants of their state’s programmes. The current study used this information to field a one-time, COVID-19-focused survey of this clinician cohort.

Invitations to participate in the survey of COVID-19 experiences were emailed to all clinicians who began serving an NHSC or state LRP or scholarship programme contract in 2018 and 2019 and were serving as of 1 July 2020. Initial survey invitations were sent on 24 November 2020, 9 months into the pandemic in the USA, and the survey closed on 7 February 2021: 83% of all responses were received by 31 December. An imbedded link on the invitation took participants to the on-line questionnaire presented on the Qualtrics 2020 platform (Qualtrics; Provo, Utah, USA). Clinicians were informed that participation was voluntary and anonymous.

Survey instrument

In this 10 min questionnaire, items addressing moral distress were part of a broader survey to understand safety net practice clinicians’ experiences during the pandemic. Other survey questions asked how the pandemic had affected clinicians’ patients, work and jobs, and queried clinicians’ stressors and well-being. Moral distress was included in this study because of its demonstrated importance to the experiences of clinicians working in hospital settings during the pandemic, and anticipating that moral distress may be particularly important to clinicians caring for low-income populations that had been most affected by the pandemic.

Moral distress measure

The notion of moral distress for clinicians was initially developed for and has continued to principally focus on hospital-based nurses for the distress nurses can experience when feeling obligated to act in ways they do not feel are morally right for patients and patients’ families.7 8 11 55 56 In recent years, the study of moral distress among clinicians has expanded to other disciplines—although still principally in the hospital setting but now also in long-term care settings—and its conceptualisation and measurement tools have broadened.8 9 22 57–59 For this study, we sought a definition and measurement tool of moral distress pertinent to the work of medical primary care, dental and behavioural healthcare practitioners working in outpatient settings in the USA, where care is typically in small practices and provided through 15–60 min patient visits, patient–practitioner relationships that often span years, and for patients living at home with their families and within communities, and supported or limited by families’ social situations. We sought a definition relevant to physicians, nurse practitioners, dentists, psychologists and others who, by nature of their training, work and licensing, generally make independent, relatively unconstrained decisions on their patients’ care.

This study conceives of moral distress as stemming from things that clinicians do or fail to do that feel morally wrong to them—consistent with original definitions of moral distress—as well as things that clinicians witness that they feel are morally wrong—consistent with the scope of items in the more recently developed and widely used Moral Distress Scale-Revised (MDS-R) and the Measure of Moral Distress for Healthcare Professionals (MMD-HP) and consistent with moral distress as conceptualised by the British Medical Association and others.7 10 57–59 To fit the work of this study’s licensed independent practitioners, we also do not limit moral distress to situations when one’s professional actions are constrained by others.8 9 11

Because our questionnaire addresses a variety of issues clinicians face during the pandemic and assesses issues for many disciplines working in many practice settings, we assess moral distress with a brief, single-item and unconstraining measurement tool, the visual analogue Moral Distress Thermometer Scale, which was developed and validated for hospital nurses by Wocial and Weaver and since also used with physicians.5 60 61 Unlike the commonly used MDS-R and the MMD-HP, the Moral Distress Thermometer does not query and sum a list of specific morally distressing experiences clinicians may have had.57–59 62 We could not assume that a list of experiences previously generated for other disciplines and settings would appropriately, accurately and fully captured the issues that morally distress primary care, dental and behavioural health clinicians working in outpatient settings for whom the causes of moral distress have been rarely assessed. In the questionnaire, clinicians were first presented with the following definition of moral distress: ‘Moral distress occurs when you witness or do things, whether required by circumstances or not, that contradict your deeply held moral and ethical beliefs and expectations.’ Immediately following this definition, participants were asked, ‘How much moral distress have you experienced related to work during the pandemic?’

Knowing that many clinicians would complete questionnaires on mobile phones with their small screens, we collapsed the Moral Distress Thermometer’s original, 11 vertically numbered response options that would not fit on some screens to a more compact 6 response options, while retaining the original 6 response anchors (none, mild, uncomfortable, distressing, intense, worst possible).63 We omitted the thermometer image displayed along the response scale because we felt not all disciplines would relate to it (NB, the original MDS, on which the Moral Distress Thermometer was based, was set on a bookmark image).60 The next, open-ended question in the questionnaire asked participants: ‘What specific issues or events caused you most moral distress during the pandemic?’, with clinicians able to identify the issues they felt caused them moral distress within the definition presented.

Public involvement

Health workforce office leaders of the 20 states with clinicians participating in this study provided consent for their state’s participation and assisted in recruiting clinicians’ participation, and two assisted as coauthors. Twenty-six clinicians working in safety net practices pilot tested the survey instrument. All clinician participants will receive a copy of this paper.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics characterise respondents’ demographics, disciplines and work settings. The percentage of respondents who reported various levels of moral distress are reported, with comparisons made across the three discipline groups (primary care, dental health and behavioural health) and the various types of practices where they worked (eg, mental health facilities and rural health clinics). Assessments for statistically significant group differences in moral distress levels are made with the Complex Samples featureof SPSS (V.26), a variant of the second-order Rao-Scott adjusted χ2 to account for clustering of the data because sometimes two or more clinicians worked in the same practice.64 The above demographic and moral distress level percentages are reported weighted for clinician subgroups that differed significantly in response rates, specifically clinicians’ discipline group (behavioural health vs primary care and dental health), the particular service programme clinicians were participating in (NHSC LRP vs joint state-federal LRPs vs NHSC Rural Community LRP and states’ service programmes vs NHSC Scholarship and NHSC Substance Use Disorder programmes), and whether clinicians were participating in the service programme at the time of the survey or had completed service within the preceding few months. Weights for the 20 strata varied from 0.62 to 1.40, and the calculated design effect due to weights was 1.037.

We conducted qualitative content analysis of clinicians’ open-ended survey item responses to understand and categorise the issues and events they reported caused them most moral distress during the pandemic.65 Three investigators initially read and discussed 4 batches of 100 responses to understand the types and range of issues that clinicians identified and how they framed them. Respondents generally indicated a moral issue (eg, people not getting needed care or being put at greater risk of infection), the group that was harmed (eg, patients, clinic staff or the public) and the person or entity said to be responsible for the harm (eg, the respondent clinician, clinic staff or society), which we used as three properties in organising codes. The three investigators then developed and refined a coding scheme by iteratively coding and discussing 5 additional batches of 70–100 responses by considering the range of issues that clinicians identified and classifying the types of issues. The final coding scheme included 28 codes that specified both the nature of the moral issue and the group affected. A separate set of eight codes classified the identified responsible person or entity.

Coding was based on what respondents explicitly stated with minimal interpretation so as not to misconstrue clinicians’ meaning in their often brief responses. Each clinician’s comment was analysed in its entirety and was assigned a moral issue and group affected code, and also a responsible party code for the person or entity said to be responsible for causing the morally distressing issue by compelling the morally distressing action or carrying out the distressing action, whichever was specified. More than one moral issue code and/or responsible party code was assigned for comments that included more than one type of moral issue and/or responsible party. Comments that noted multiple examples of the same moral issue and/or responsible party received a single moral issue code and/or single responsible party code.66

We applied this coding scheme to open-ended responses in a one-third sample of completed questionnaires, that is, responses in every third group of 100 sequentially completed questionnaires. Two investigators—a graduate student in a non-health field trained in qualitative research and a senior medical student with some content experience and knowledge but no prior familiarity with qualitative research—independently coded all responses. Inter-rater reliability assessed for responses from questionnaires not used in developing the coding scheme was acceptable for both moral issue and harmed group codes (kappa=0.83, 95% CI, 0.80 to 0.86) and responsible person or entity codes (kappa=0.83, 95% CI 0.79 to 0.86).67 A third investigator, an experienced qualitative and quantitative researcher and clinician familiar with care in safety net practices and clinicians’ issues there, identified coding differences, which were settled through a combination of discussion and consensus, majority rule, and relying on the third reviewer’s insights.

To simplify the presentation of findings, we combined codes that had few mentions and were conceptually similar to generate a more manageable set of 11 moral issue and affected group codes and 7 codes for the responsible party. Each moral issue and its most commonly identified responsible party(ies) are briefly explained and representative quotes provided aiming to convey both the most common and range of reported issues falling within each category of moral distress (fair dealing).68 The number of mentions of issues falling into each category of moral distress/affected group and each category of responsible party, as well as their percent of all issues mentioned, are presented to convey a sense of which issues are more versus less common for these clinicians.65 69 Statistical weights are not applied to these percentage estimates as precise extrapolation to a target sample is inappropriate in qualitative research.70 Among respondents whose most distressing situation fell into each of the issue types, we also compare the percentage who reported higher levels of moral distress (ie, distress levels of ‘distressing’, ‘intense’ or ‘worst possible’).65

Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation; Redman, Washington, USA) was used to manage data during coding of participants’ typically brief responses with codes subsequently used in quantitative analyses (ie, counts and group frequency comparisons).71 Quantitative analyses were run with SPSS V.26. A p value of 0.05 was set for statistical significance.

Results

Of the 4647 clinicians surveyed, 80 email addresses failed. Of the remaining 4567 clinicians, 2073 responded to the questionnaire including its item on degree of moral distress (45.6%). Most respondents (54.9%) were 35–49 years old, with one-third (30.4%) younger than 35 years and 14.6% were 50 years or older. Nearly three-quarters (72.9%) were women, and most (60.2%) had children at home. A strong majority were white (81.0%), with fewer being black or African American (6.8%), Asian (7.2%) and other or multiple races (5.0%). Hispanic ethnicity was reported by 9.8%.

Degree of moral distress

Among all respondents, the mean reported level of moral distress during the pandemic was 1.58, which is about midway between ‘mild’ and ‘uncomfortable’ on the six-point ordinal scale from ‘none’ to ‘worst possible’. A total of 28.4% reported that they experienced no moral distress, 44.8% reported ‘mild’ or ‘uncomfortable’ levels of moral distress and 26.8% characterised their moral distress as ‘distressing’, ‘intense’ or ‘worst possible’ (table 1). Primary care, dental and behavioural health clinicians were similar in their proportions at these three grouped levels of moral distress (p=0.28). Moral distress levels were also similar for clinicians working across the various types of safety net practices (p=0.058).

Table 1.

Reported degree of moral distress related to work experienced during the pandemic, by discipline and practice setting

| Degree of moral distress (Weighted %) |

||||

| n | None (n=588) |

Mild or uncomfortable (n=931) |

Distressing, intense or worst possible (n=554) |

|

| All respondents | 2073 | 28.4% | 44.8% | 26.8% |

| Discipline | ||||

| Primarcare combined* | 1097 | 27.9% | 45.1% | 27.1% |

| Physician | 354 | 27.6% | 47.4% | 25.0% |

| Physician assistant | 228 | 30.7% | 45.1% | 24.2% |

| Advanced practice nurse | 515 | 26.7% | 43.6% | 29.6% |

| Dental health combined | 294 | 33.4% | 43.1% | 23.5% |

| Dentist | 255 | 33.2% | 44.2% | 22.6% |

| Dental hygienist | 39 | 36.4% | 36.4% | 27.3% |

| Behavioural health combined | 682 | 26.9% | 45.1% | 28.0% |

| Licensed professional counsellor | 223 | 27.6% | 43.3% | 29.1% |

| Licensed clinical social worker | 241 | 25.0% | 43.6% | 31.4% |

| Psychologist | 104 | 28.6% | 46.9% | 24.5% |

| Other Behavioural health | 114 | 28.4% | 50.5% | 21.1% |

| Practice setting† | ||||

| FQHC-CHC | 1083 | 29.3% | 44.2% | 26.5% |

| Mental health or SUD facility | 260 | 30.2% | 45.5% | 24.3% |

| Indian health service or tribal site | 215 | 22.6% | 45.7% | 31.7% |

| Rural health clinic | 145 | 30.7% | 39.4% | 29.9% |

| Correctional facility | 41 | 12.8% | 43.6% | 43.6% |

| Other office-based site | 296 | 30.4% | 46.9% | 22.7% |

| Hospital-based site | 33 | 17.9% | 60.7% | 21.4% |

*Second-order Rao-Scott adjusted χ2 test for differences in group proportions for the combined disciplines of the primary care, dental health and behavioural health groups, p=0.28.

†Second-order Rao-Scott adjusted χ2 test for differences in group proportions across seven practice settings, p=0.058.

FQHC-CHC, Federally Qualified Health Center-Community Health Center; SUD, substance use disorder.

Reports of issues causing clinicians most moral distress

The 1485 clinicians who reported experiencing moral distress during the pandemic were asked what specific issues or events caused them most moral distress: 1168 (78.6%) provided open-text responses. Responses varied in length from a single word (eg, ‘death’) to several paragraphs. Of the 411 clinicians whose comments were randomly selected for qualitative analysis, 336 identified a single morally distressing issue and 75 identified two or more issues, generating a total of 508 mentions of issues for analysis.

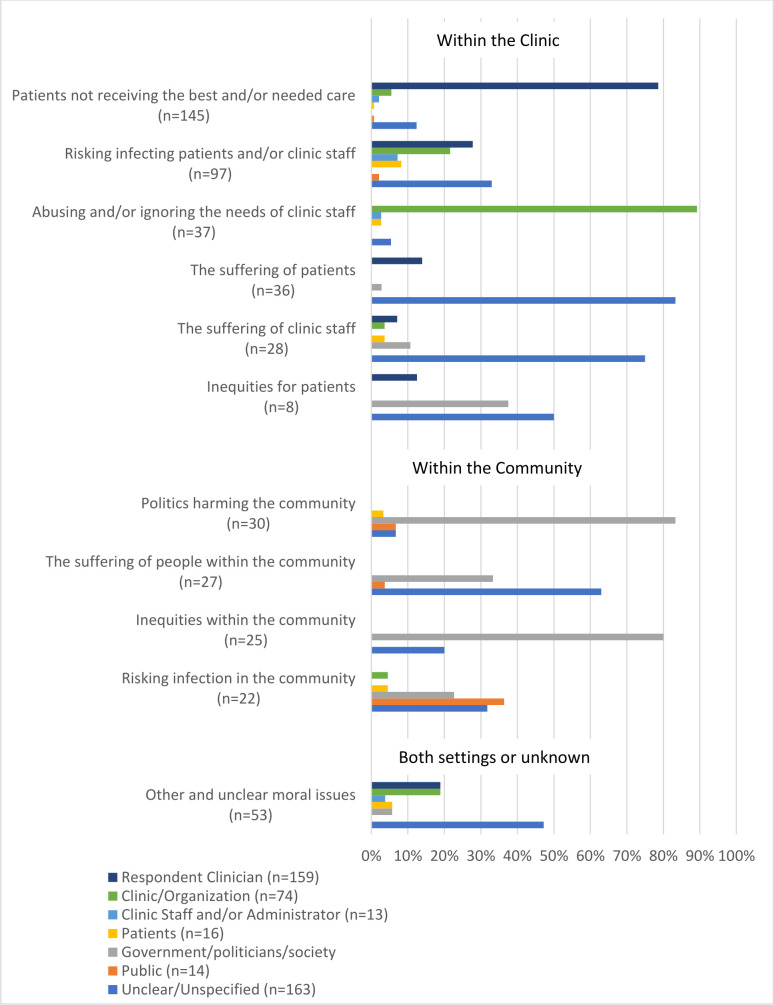

Responsible persons and entities

In clinicians’ descriptions of morally distressing issues that identified a person or party as responsible, it was most often clinicians themselves (31% of all issues mentioned) (table 2). In most cases, these were situations where clinicians felt they had not provided needed care or had provided suboptimal care to patients because of the exigencies of the pandemic or the requirements of their practices. Clinicians’ clinics or organisations were the second most commonly noted responsible party (15%), followed by government, politicians or society (14%), patients (3%), the public (3%) and clinic staff and/or administrators (3%). For one-third of the morally distressing issues reported, the responsible party was unclear or not identified. Many comments that did not identify a responsible party spoke of situations that were widely known to occur during the pandemic and have been frequently highlighted in the lay press, for example, ‘patient dying alone;’ ‘watching outbreaks unfold in nursing homes’. The lack of a named responsible party in these situations was believed by coders to indicate that clinicians were not assigning responsibility to anything other than the pandemic itself.

Table 2.

Persons or entities that clinician’s comments identified as responsible for the issues they found most morally distressing (n=508 comments)

| Responsible person or entity | Representative comments |

| The clinician–respondent (n=159; 31% of all responsible parties) |

Not being able to provide care of the same quality as pre-pandemic; having to cancel on clients to take care of myself; Being unable to treat patients in need because my clinic closed |

| The clinician’s clinic or organisation (n=74; 15% of all responsible parties) |

My clinic wasn't telling staff or clients when there were positive covid cases in the building and i was told not to as well; The conflict between organization pushing for in person visit when often telemedicine would be more appropriate |

| Government/politicians/society (n=69; 14% of all responsible parties) |

Poor handling of covid at federal and state levels; the failure of presidential leadership; racism, hatred, lack of moral responsibility shown by others |

| Patients (n=16; 3% of all responsible parties) |

Patients coming into the consult room and taking off their mask; patients dishonesty during screening process |

| The public (n=14; 3% of all responsible parties) |

Lack of social responsibility of others to wear a mask; Anti-maskers/Conspiracy Theorists/ Anti-vaxxers |

| Clinic staff and/or administrator (n=13; 3% of all responsible parties) |

Providers/staff not following covid protocols; a decline in the medical staff treatment of some of the pts; My MA declining covid testing… while family at home had covid. |

| Unspecified/unclear/other (n=163; 32% of all responsible parties) |

My clients anxiety; Needless deaths; Potential to exposure; Forced lock downs. covid screening and testing |

Morally distressing issues

Table 3 presents the 11 categories that clinicians’ reported morally distressing issues fell into, with representative verbatim comments. The percentage of each individual or entity identified as responsible for each of the morally distressing issues is shown in figure 1. The percentage distribution of comments falling into the 11 categories of morally distressing issues was comparable for primary care, dental health and behavioural clinicians (p=0.123), with one exception: compared with primary care and behavioural health clinicians, dental health clinicians more often reported issues related to risking infecting patients and clinic staff (17.0% vs 35.1%, respectively; p=0.005).

Table 3.

Categories of morally distressing issues with representative comments (n=508 comments)

| Morally distressing issue category | Representative comments |

| Within the clinic | |

| Patients not receiving the best and/or needed care (n=145; 29% of all issues) |

Performing telehealth visits that really require in person evaluation; Not having the resources to always help my patients; telling people they couldn't have dental care because it wasn't emergent; Not able to provide the quality of care I would like to |

| Risking infecting patients and/or clinic staff (n=97; 19% of all issues) |

Worrying about infecting others with covid if i am asymptomatic; Had to reuse N95 mask for two to four weeks; Assuring my family health with client’s not following protocol (including masks); My clinic wasn't telling staff or clients when there were positive covid cases in the building and I was told not to as well. |

| Abuse of staff or ignoring their needs (n=37; 7% of all issues) |

Overworking staff; Lack of support/appreciation from administration; Lack of PTO being allowed; Feeling like my safety and the safety of my team is not a priority and we are not valued except to keep money coming in… |

| The suffering of patients (n=36; 7% of all issues) |

Patients passing away from Covid, huge number of them infected; Increased use of drugs/alcohol as a coping mechanism by patients; Listening to patients who have been affected by the pandemic |

| The suffering of clinic staff (n=28; 6% of all issues) |

Uncertainty of employment; Being unable to validate some of my team when they are struggling; Work stress; Colleagues getting sick or having family members die. |

| Inequities for patients (n=8; 2% of all issues) |

Seeing how my patient population has been disproportionately affected by illness and death because of socioeconomic issues; Seeing patients unable to get their healthcare needs met due to financial circumstances, inability to obtain health insurance, loss of income, etc… |

| Within the community | |

| Politics in the community (n=30; 6% of all issues) |

Political approach to the pandemic; Politicians behavior, behavior of their supports; politics and collision with medicine/science |

| The suffering of people in the community (n=27; 5% of all issues) |

Hearing or seeing others struggle; increase in poverty and suicides; Forced lock downs; knowing that elderly people in nursing homes were contracting and dying from the virus due to employees or family members infecting them. Very sad and irresponsible. |

| Inequities and injustice within the community (n=25; 5% of all issues) |

racial injustice, lack of access to healthcare; The disproportionate effect of COVID-19 on minority and impoverished communities; The ongoing racism and racial inequality experienced by BIPOC. |

| Risking infecting people in the community (n=22; 4% of all issues) |

Lack of community commitment for COVID safeguards; Lack of social responsibility of others to wear a mask; Lack of compliance with CDC recommendations in my community… |

| Unclear issues | |

| Unclear/uncertain/other issue (n=53; 10% of all issues) |

My patients; Helping to run the COVID clinic; decisions made by management; Being asked to screen patients for covid symptoms despite no medical training; COVID 19 vaccines |

Figure 1.

Responsible person or entity (%) identified for each morally distressing issue, n=508 issue mentions.

The 11 categories of morally distressing issues and common subcategories within each follow below.

1. Patients not receiving the best and/or needed care (principal responsible party: the clinician–respondent (figure 1)). This was the most commonly reported group of morally distressing issues, comprising 29% of all issues mentioned (table 2). The limitations of telehealth and virtual care for patients were commonly mentioned, noting that they were often inadequate for appropriate care and posed a barrier to care for some patients.

we’ve primarily done phone/telehealth. There are times I have anxiety related to ‘what if I've missed’ something because I'm unable to see the person in full. (Nurse practitioner, Oregon)

Providing care by telephone. Don’t feel that I can connect with clients in the same meaningful way. (Physician, Alaska)

Having to move patients to telehealth even though they themselves may not have the resources to access telehealth services. (Licensed Professional Counselor, Minnesota)

Other clinicians expressed that various circumstances of the pandemic limited what they could do for patients.

Not being able to provide care of the same quality as pre-pandemic. (Nurse Practitioner, California)

Some clinicians noted that their clinic’s decisions and protocols meant to limit COVID-19 exposure to patients and staff or bolster practice finances affected patients’ quality or access to care.

Not being able to provide the care I'd like. Financial decisions negatively affecting patient care. (Nurse Practitioner, Arizona)

2. Risking infection of patients and/or clinic staff (principal responsible parties: the clinician–respondent and their clinic/organisation). Comments related to circumstances that placed patients and clinic staff at risk of COVID-19 infection were the second most common type mentioned (19% of total), and were the most frequently reported morally distressing issue for dental clinicians (35% of their comments). Shortages of PPE were frequently mentioned, as was the importance of balancing patients’ needs for in-person care with the infection risks this carried for them and clinic staff.

Worrying about keeping my employees safe, vs the importance of client care. (Licensed Clinical Social Worker, Oregon)

Got infected with COVID and my wife got infected because I was exposed at work. (Physician, North Dakota)

3. Abuse of staff and/or ignoring their needs (principal responsible party: the clinic/organisation). Some clinicians felt that their clinics made operational decisions without adequate regard for the effects on clinicians and other staff. Some felt their health was inadequately protected by their organisations and that their needs as people and employees were unheeded.

All our manager and director seem to care about us making money and how many patients we see. I was having to balance being exposed to so many patients then going home to my family and potentially exposing them. (Dentist, Arizona)

Organization not properly testing or protecting employees. Not providing hazard pay [or] providing FMLA (Physician Assistant, South Carolina)

4. The suffering of patients (principal responsible party: unspecified/unclear/other). Some clinicians noted the tragedy of the pandemic’s toll on their patients’ physical health, mental health, work and families, and how difficult it was for them, as their clinicians, to witness this.

Seeing how it has impacted families in our clinic and feeling powerless to make meaningful change. (Nurse Practitioner, North Carolina)

More clients in crisis and dealing with high anxiety. There has been less access to resources and supports for them in the community, which leaves me feeling helpless as a clinician. (Licensed Clinical Social Worker, Oregon)

5. The suffering of clinic staff (principal responsible party: unspecified/unclear/other). Clinicians recounted illnesses among coworkers (eg, ‘My nurse dying from complications of Covid;’ ‘Colleagues getting sick or having family members dies’), and fears of illness for themselves. Others spoke of employment challenges (eg, ‘job security;’ ‘partial lay off, decreased hours, having to find a new job for more income’). Still others spoke of feeling overwhelmed (eg, ‘Continual stress buildup, fear of an unknown outcome;‘ ‘Juggling too much’).

6. Inequities for patients (principal responsible parties: unspecified/unclear/other and the government/politicians/society). A few clinicians remarked that their patients suffered disproportionately during the pandemic because they were a marginalised group, could not afford care, or there were no services available for them.

Diagnosing patients experiencing homelessness with COVID and not being able to provide them with a safe place to isolate/recover. (Physician, California)

The next four types of morally distressing issues listed below—encompassing 20% of all comments—occurred outside of clinicians’ practices within their communities, states or nationally. These issues were not specifically noted to affect clinicians’ patients or their care, but seemingly distressed clinicians given their knowledge of and concern about health, healthcare, public health, science and social justice. The government, politicians and society were frequently identified as causing these issues, but often the cause was unspecified or unclear.

7. Politics in the community (principal responsible party: the government/politicians/society). Politics and politicalised issues—the elections, the politisation of the pandemic, conflicts between people with different political views—were mentioned as morally distressing because they created conflict and upset society, and sometimes for how it affected clinicians’ work and families.

Anti-science movement, lack of leadership, CDC tarnished, politics, politization of health measures. (Physician Assistant, North Carolina)

The politicization of science and mask wearing has been very upsetting as it has put my life and my family’s life at risk… when these people get a severe toothache, they expect to be seen by a dentist, who’s very life is put at risk by their anti-mask behaviors with I am put in a position to provide oral healthcare. (Dentist, Nebraska)

8. The suffering of people in the community (principal responsible party: unspecified/unclear/other). Mentions of the suffering of people in the community generally mirrored the suffering that other clinicians noted for their patients, including the pandemic’s impact on people’s physical health, mental health and financial situations. A few comments were about community suffering due to public health measures and other government responses to the pandemic.

The way we are handling ‘the numbers’ as a nation, closing schools, putting child’s development and wellbeing in danger… (Nurse Practitioner, Kentucky)

9. Inequities and injustice within the community (principal responsible party: the government/politicians/society). The issues mentioned centred around racism and social injustice (‘BLM;’ ‘George Floyd;’ ‘racial injustice;’ ‘racism’) and disparities in health and healthcare (‘Exacerbation of health disparities;’ ‘Witnessing health inequalities and disparities’)

10. Risking infecting people in the community (principal responsible party: various). Comments in this category uniformly spoke of people not wearing masks or otherwise failing to follow the CDC’s protocols to mitigate the pandemic’s spread. Some comments were about people showing no concern or sense of responsibility for one another.

witnessing people not wear masks or following CDC guidelines (Dentist, Montana)

Lack of concern of people for others' wellbeing (selfishness) (Physician, Arizona)

11. Unclear/uncertain/other issue (principal responsible parties: various). Some comments were too brief and without sufficient details or context to know what specifically about the issue mentioned was morally distressing to the clinician. For example, the comment ‘telehealth or phone’ might be intended to indicate the inadequacies of telehealth but alternatively that the practice could not offer telehealth.

Relationship between the moral distress issue cited and the amount of moral distress reported

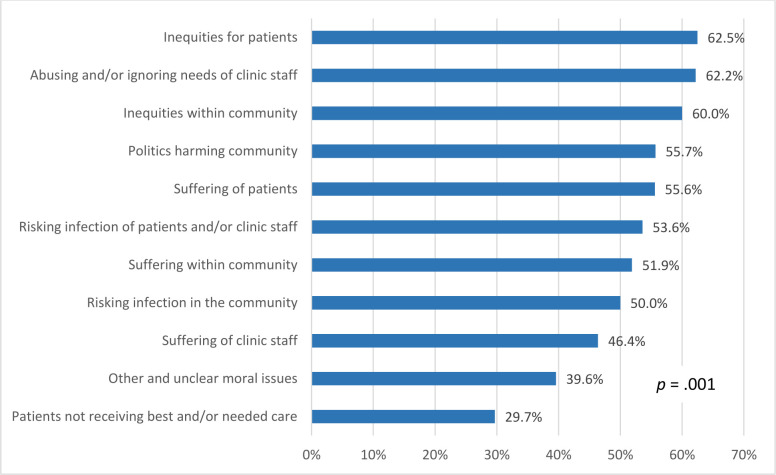

Clinicians whose open-ended comments fell across the 11 categories of moral distressing issues varied in their likelihood of reporting a higher level—distressing, intense or worst possible—of distress, ranging from 29.7% to 62.5% (p=0.001) (figure 2). Clinicians most likely to rate their moral distress in the higher level range reported distressing issues in the categories of inequities for patients, abusing and/or ignoring the needs of clinic staff, and inequities within the community. Clinicians who least often rated their moral distress in the higher range reported issues related to patients not receiving the best and/or needed care, an unclear/uncertain/other issue, and the suffering of clinic staff.

Figure 2.

Percentage of respondents who reported a distressing, intense or worst possible level of moral distress (vs mild or uncomfortable level) among clinicians who reported each type of most morally distressing issue, n=508 issue mentions.

Discussion

In this study of clinicians working in outpatient safety net practices of many types and locations in the USA during the first 9 months of the COVID-19 pandemic, 71.6% reported experiencing moral distress related to their work. Most characterised their moral distress as ‘mild’ or ‘uncomfortable,’ but one-quarter (26.8%) of all clinicians described their moral distress levels as ‘distressing,’ ‘intense’ or ‘worst possible.’ Moral distress levels were similar for primary care, dental and behavioural health clinicians, and similar for clinicians working in the various types of safety net practices. Prior studies of other, principally hospital-based clinician groups have similarly found moral distress during the first year of the pandemic was mild for most.4 5 72

The most commonly mentioned issues that this study’s clinicians found most morally distressing were when their patients were not receiving the best or all needed care and the infection risks faced by patients and staff within the clinic. Not providing best and all needed care were also issues that clinicians working in other settings found morally distressing during the pandemic.4 5 10 13 Among hospital-based clinicians, this was often from having little to offer critically ill COVID-infected patients early in the pandemic, shortages of ICU beds and respirators, and issues of fairness in rationing when local infection and hospitalisation rates peaked. In contrast, this study’s outpatient clinicians noted moral distress from suboptimal and limited care when offices closed completely early in the pandemic and then later reopened but for safety reasons restricted the types of care provided and numbers of patients seen, as well as from using telehealth even when clinicians felt it was inadequate for patients’ needs. These operational changes were ubiquitous for US outpatient practices during the pandemic’s first year, including for the safety net practices where this study’s clinicians worked.16 47 73–75

Other things witnessed within offices during the pandemic that morally distressed clinicians included the suffering of patients and clinic staff and the mistreatment and abuse of staff. That outpatient clinicians’ moral distress sometimes stemmed from observing the suffering and mistreatment of staff expands the understanding that moral distress from work for clinicians only occurs from actions affecting patients and their families. When at work clinicians are around both patients and coworkers, and both groups have moral standing, that is their ‘interests matter intrinsically… in the moral assessment of actions and events’.76 Therefore, both groups can be morally wronged. Thus, it is not surprising that clinicians can be morally distressed when their coworkers are treated unfairly or otherwise suffer, just as they can be morally distressed when these things happen to patients.

Previous studies and fixed-response option survey instruments of moral distress for clinicians have focused on issues occurring within healthcare settings, typically the hospital.57 58 62 Clinicians in this study were presented with a definition of moral distress that did not limit it to the consequences of restricted actions, and through its open-ended, unconstrained query of perceived causes of moral distress during the pandemic clinicians reported many health-related issues occurring outside healthcare settings, such as people not wearing masks in public. The definition of moral distress provided to this study’s clinicians specified distress from issues ‘related to work during the pandemic’. It is likely that outpatient clinicians view the community’s failure to heed public health mandates has been relevant to their work, as it affects local infection rates and, in turn, the number of infected patients they will see in the office, infection risks thereby faced by clinicians and staff, and their offices’ ability to provide care to patients with other needs. Other clinicians reported moral distress from issues not even directly related to health, such as the pandemic’s financial impact on families. These clinicians evidently found the pandemic’s effects on non-health care related aspects of people’s lives more morally distressing and thus more salient to report than its disruptions to the health and care of patients. It may also be that some clinicians simply had not read or heeded the definition of moral distress provided.

Within the common bioethical framework of principlism, not providing best or all needed care and infecting others violate clinicians’ moral obligations of beneficence and non-maleficence, that is to help patients to the best of a clinicians’ ability and to not cause them harm.22 77 These are also the two moral principles central in the original framing of moral distress among intensive care unit nurses, who can feel compelled to provide care to patients that they believe is futile or harmful.78

Some of the broader range of issues found morally distressing to this study’s outpatient clinicians violate a third fundamental bioethical principle: justice. Injustices were observed during the pandemic when certain patient groups and communities faced barriers to care, health disparities and social injustices. Significantly, clinicians’ level of moral distress was more often in the high range for those who provided examples of inequities and other injustices for patients (62.5%) and within the community (69.0%) than among clinicians who cited examples of patients not receiving the best and all needed care (29.7%). The latter have been commonly mentioned sources of moral distress for clinicians during the pandemic, but for these clinicians they were less often the cause of great moral distress.12 79 80 It is not surprising that inequalities and other injustices can cause significant moral distress for clinicians working in safety net practices, who were motivated in their careers to care for patients facing economic, other social and geographic barriers to care, often for lower pay.

The fourth common bioethical principle, autonomy, was reflected in the comments of just a few clinicians who reported moral distress from the pandemic’s public health mandates, such as the requirement to wear masks, that constrained individual freedoms.

In the morally distressing actions that clinicians themselves had carried out or failed to carry out, their words often indicated they felt compelled to do so, through statements such as, ‘Not being able to provide care…’ and ‘Being unable to treat patients…’, often evidently forced by circumstances unavoidable in the pandemic. Some clinicians perceived the pandemic created conflicts between their individual-focused clinical ethics—making decisions that are best for patients as individuals and respecting their autonomy—and society’s public-focused ethics, thats is, prioritising the population’s health and other needs.6 22 Some clinicians indicated that their clinic or its parent organisation made decisions that caused their moral distress, most often policies perceived to pay inadequate attention to the needs of staff or that risked infecting clinic staff and patients. Some clinicians acknowledged the clash between their clinics’ corporate values and clinicians’ own better understanding and prioritisation of people’s health, safety and best care: ‘This company’s ongoing quest to put profits over people’. Even when clinicians viewed circumstances of the pandemic or their employers’ decisions had compelled them to alter how many and which patients they saw and how care was provided, they sometimes overtly stated that they felt bad about their role in carrying out these altered care requirements, expressed in statements such as ‘feeling like my work isn’t enough, that my clients need more than I can give,’ and ‘feeling like I’m not adequately helping clients via telehealth’.

In the absence of studies of moral distress among outpatient and safety net practice clinicians prior to the current pandemic, we cannot be certain that the distress measured here at 9 months into the pandemic is greater than if measured in 2019 or earlier. But most issues these clinicians reported caused moral distress during the pandemic related directly or indirectly to the pandemic, thus their moral distress had likely increased during the pandemic. Their moral distress may have increased further since this late 2020/early 2021 survey, as vaccines have since become widely available but then shunned by many people, prolonging the pandemic and causing many needless deaths.81

This study has several important limitations. Its 45.8% response rate is strong for a survey of clinicians but can still allow response bias. This was addressed through statistical reweighting to the target study population in analyses of demographics and quantifying levels of moral distress. If response bias remained, it would have affected the levels of moral distress measured and group comparisons, but not likely the range of issues identified as morally distressing to these clinicians. The reported frequencies of the various types of morally distressing issues and responsible parties, derived from mentions in qualitative analyses, should be understood only to show the issues most and least commonly mentioned and not taken as meaningful frequency point estimates for the target population.65 69

Clinicians’ interpretation of the original single question Moral Distress Thermometer measurement tool and its adaptation for this study, as well as some other aspects of their validity, have not been assessed.58 Further, relying on open-ended written response data gave us no opportunity to clarify clinicians’ responses or allow us to understand the fuller context, meaning and significance of the issues they report. This should be addressed in future studies.

In terms of generalisability, this study assessed moral distress in a subset of US safety net clinicians who participated in service-requiring education loan repayment and scholarship programmes. Although this cohort is broad in its disciplines and in the types of safety net practices where clinicians work, its experiences may not fully reflect that of other clinicians working in their safety net practices, who are more likely to be older and in leadership positions because of their seniority. Some but not all studies of moral distress among critical care nurses find that nurses who are more experienced are less likely to experience moral distress.82

Conclusions and implications

This study expands the understanding of the moral distress of clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic beyond those working in hospitals by assessing moral distress among clinicians working in US outpatient practices that focus on care for poor and otherwise socially vulnerable patients. It finds that most clinicians working in safety net practices experienced moral distress during the pandemic’s first year, with one-quarter characterising its intensity as ‘distressing’ or greater. Moral distress frequently stemmed from the operational changes that many US practices made in response to the pandemic, such as restricting services and the number of office appointments offered each day which delayed care for patients, and requiring virtual visits even when clinicians felt that face-to-face visits provided better care. Within this unique population of clinicians whose work focuses on care for the poor, some reported that injustices observed for patients, staff and within the community caused them most moral distress during the pandemic, and these particular clinicians more often reported higher levels of moral distress. Other clinicians found the mistreatment and abuse of clinic staff during the pandemic most morally distressing. These findings expand the types of issues recognised as causing moral distress for clinicians beyond prior studies’ focus on moral distress from care that does not best serve patients. Future studies should assess whether other clinician groups, including those working in other types of outpatient practices and within hospitals, can also be morally distressed at work by mistreatment of health care staff and witnessing injustices.

Moral distress for clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic has occurred alongside and contributed to their stresses from other sources and to their emotional exhaustion, adverse mental health and burnout.4 5 15 83–86 The consequences of moral distress for these safety net practice clinicians at the levels found and for the issues reported remains to be demonstrated but are likely meaningful: moral distress for clinicians in other settings is associated with disengagement from patients, poorer quality of care and burnout.13 29–34 Of particular importance to the future staffing of safety net practices, clinicians morally distressed by perceived unjust or otherwise harmful policies made by their safety net practices may be more likely to join the ‘Great Resignation’ and look for work elsewhere.29 30 87 88 On the other hand, clinicians’ retention in their practices may not be affected when they are morally distressed by things perceived to be unavoidable during the pandemic or otherwise not due to their practices, especially if their experiences during the pandemic strengthened their sense of meaning in work and thus the importance of their jobs.47 86 89

Various approaches have been suggested to reduce moral distress among clinicians. Managers of outpatient practices should understand what moral distress means for clinicians and its importance to them, create supportive work environments, create ways for clinicians and staff to learn and talk about moral distress and safely raise morally distressing issues, identify and address any ongoing sources of moral distress, and provide clinicians with needed psychological support and time away from work.10 12 86 90 91 Clinicians should be involved in operational decisions made during challenging times—indeed, all times—so that decisions can be informed by their perspectives and clinicians can better understand the choices available to their practices and reasoning behind the decisions made that affect them, their colleagues and their patients.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: DP is the guarantor of this study, having contributed to the conceptualisation and design of this study, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation. JS contributed to the conceptualisation and design of this study, analysis and interpretation. TER contributed to the conceptualisation and design of this study, acquisition of data and interpretation. KA contributed to the data analysis and interpretation. ASH contributed to the data analysis and interpretation. JNH contributed to the conceptualisation and design of this study, acquisition of data and interpretation. All named authors contributed to drafting and critically revising this manuscript for its intellectual content, give final approval to the resubmitted draft and agree to be held accountable for this study and paper’s accuracy and integrity.

Funding: This study is funded through the Carolina Health Workforce Research Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill with funds from the Health Resources and Services Administration of the US Department of Health and Human Services as part of award U81HP26495 totaling US$525 465. Additional support was provided by grant CTSA-UL1TR002489 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, US National Institutes of Health. The contents are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement by, HHS, NIH, the US Government or the authors’ employers.

Competing interests: TER and JNH work in public agencies that operate or are affiliated with loan repayment programs whose clinicians are included in this study. Other authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Access to deidentified, open-text survey responses will be available 2 years after article publication to researchers who provide a methodologically sound proposal to achieve specific articulated aims. Proposals should be directed to the project’s lead investigator (don_pathman@unc.edu). A data access agreement will be required that spells out the requester’s data protection procedures, requirements to protect subject confidentiality and that limits the use of data to the agreed upon purpose.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

A human subjects exemption was approved for this study by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Non-Biomedical IRB of the Office of Human Research Ethics 0543 FWA #4801, Reference ID 319209. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1. Taylor A. Photos: the reality of the current coronavirus surge, 2020. The Atlantic. Available: https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2020/12/photos-reality-current-coronavirus-surge/617277/ [Accessed 17 Nov 2021].

- 2. Stockton A, Death KL. through a nurse’s eyes. Opinion. New York Times 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bravata DM, Perkins AJ, Myers LJ, et al. Association of intensive care unit patient load and demand with mortality rates in US department of Veterans Affairs hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2034266. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.34266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Donkers MA, Gilissen VJHS, Candel MJJM, et al. Moral distress and ethical climate in intensive care medicine during COVID-19: a nationwide study. BMC Med Ethics 2021;22:73. 10.1186/s12910-021-00641-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Miljeteig I, Forthun I, Hufthammer KO, et al. Priority-setting dilemmas, moral distress and support experienced by nurses and physicians in the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in Norway. Nurs Ethics 2021;28:66–81. 10.1177/0969733020981748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Akram F. Moral injury and the COVID-19 pandemic: a philosophical viewpoint. Ethics Med Public Health 2020;18. 10.1016/j.jemep.2021.1006617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jameton A. Nursing practice: the ethical issues. Prentice Hall, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fourie C. Who is experiencing what kind of moral distress? distinctions for moving from a narrow to a broad definition of moral distress. AMA J Ethics 2017;19:578–84. 10.1001/journalofethics.2017.19.6.nlit1-1706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McCarthy J, Deady R. Moral distress reconsidered. Nurs Ethics 2008;15:254–62. 10.1177/0969733007086023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. British Medical Association . Moral distress and moral injury. recognising and tackling it for UK doctors, 2021. Available: https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/nhs-delivery-and-workforce/creating-a-healthy-workplace/moral-distress-in-the-nhs-and-other-organisations [Accessed 23 Jun 2021].

- 11. Rodney PA. What we know about moral distress. Am J Nurs 2017;117:S7–10. 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000512204.85973.04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Morley G, Sese D, Rajendram P, et al. Addressing caregiver moral distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cleve Clin J Med 2020;88. 10.3949/ccjm.87a.ccc047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Norman SB, Feingold JH, Kaye-Kauderer H, et al. Moral distress in frontline healthcare workers in the initial epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States: relationship to PTSD symptoms, burnout, and psychosocial functioning. Depress Anxiety 2021;38:1007–17. 10.1002/da.23205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. O'Neal L, Heisler M, Mishori R, et al. Protecting providers and patients: results of an Internet survey of health care workers' risk perceptions and ethical concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Emerg Med 2021;14:18. 10.1186/s12245-021-00341-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Richardson D. HERO registry community provides insight into moral injury among healthcare workers, 2021. Available: https://heroesresearch.org/hero-registry-community-provides-insight-into-moral-injury-among-healthcare-workers/ [Accessed 30 Oct 2021].

- 16. Song Z, Giuriato M, Lillehaugen T. Economic and clinical impact of COVID-19 on provider practices in Massachusetts. NEJM Catalyst 2020. 10.1056/CAT.20.0441 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. American Dental Association . COVID-19 economic impact— state dashboard. Available: https://www.ada.org/resources/research/health-policy-institute/impact-of-covid-19/covid-19-economic-impact-state-dashboard [Accessed 3 Jul 2022].

- 18. The Physicians Foundation . Survey of American’s Physicians: COVID impact edition, 2020. Available: https://physiciansfoundation.org/physician-and-patient-surveys/2020physiciansurvey/ [Accessed 03 Jul 2022].

- 19. American Academy of Family Physicians National Research Network,, Robert Graham Center . COVID-19 survey report – week eight. Available: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwjDu6Lxy934AhU [Accessed 03 Jul 2022].

- 20. Simon J, Mohanty N, Masinter L, et al. COVID-19: exploring the repercussions on federally qualified health center service delivery and quality. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2021;32:137–44. 10.1353/hpu.2021.0013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Verma S. Early impact of CMS expansion of Medicare telehealth during COVID-19, 2020. Health affairs Blog. Available: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20200715.454789/full/ [Accessed 20 Mar 2021].

- 22. Kherbache A, Mertens E, Dennier Y. Moral distress in medicine: an ethical analysis. J Health Psychol 2021;00:1–20. 10.1177/13591053211014586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kaufman HW, Chen Z, Niles J, et al. Changes in the number of US patients with newly identified cancer before and during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2017267. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.17267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Garcia S, Albaghdadi MS, Meraj PM, et al. Reduction in ST-segment elevation cardiac catheterization laboratory activations in the United States during COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;75:2871–2. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lai AG, Pasea L, Banerjee A, et al. Estimated impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer services and excess 1-year mortality in people with cancer and multimorbidity: near real-time data on cancer care, cancer deaths and a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open 2020;10:e043828. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rich-Edwards JW, Ding M, Rocheleau CM, et al. American frontline healthcare personnel's access to and use of personal protective equipment early in the COVID-19 pandemic. J Occup Environ Med 2021;63:913–20. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000002308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Timmermann J. Kantian duties to the self, explained and defended. Philos 2006;81:505–30. [Google Scholar]

- 28. American Medical Association . Code of medical ethics opinion 9.3.1. Physician Health & Wellness. Available: https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/physician-health-wellness [Accessed 30 Jun 2022].

- 29. Austin W, Rankel M, Kagan L, et al. To stay or to go, to speak or stay silent, to act or not to act: moral distress as experienced by psychologists. Ethics Behav 2005;15:197–212. 10.1207/s15327019eb1503_1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Henrich NJ, Dodek PM, Gladstone E, et al. Consequences of moral distress in the intensive care unit: a qualitative study. Am J Crit Care 2017;26:e48–57. 10.4037/ajcc2017786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dodek PM, Norena M, Ayas N, et al. Moral distress is associated with general workplace distress in intensive care unit personnel. J Crit Care 2019;50:122–5. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.11.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Elpern EH, Covert B, Kleinpell R. Moral distress of staff nurses in a medical intensive care unit. Am J Crit Care. In Press 2005;14:523–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fumis RRL, Junqueira Amarante GA, de Fátima Nascimento A, et al. Moral distress and its contribution to the development of burnout syndrome among critical care providers. Ann Intensive Care 2017;7:71. 10.1186/s13613-017-0293-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Abbasi M, Nejadsarvari N, Kiani M, et al. Moral distress in physicians practicing in hospitals affiliated to medical sciences universities. Iran Red Crescent Med J 2014;16:e18797. 10.5812/ircmj.18797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Institute of Medicine . America’s Health Care Safety Net: Intact but Endangered, 2000. The National Academies Press. Available: https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/9612/americas-health-care-safety-net-intact-but-endangered [Accessed 10 May 2022]. [PubMed]

- 36. Moore JT, Ricaldi JN, Rose CE, et al. Disparities in Incidence of COVID-19 Among Underrepresented Racial/Ethnic Groups in Counties Identified as Hotspots During June 5-18, 2020 - 22 States, February-June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1122–6. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6933e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Karmakar M, Lantz PM, Tipirneni R. Association of social and demographic factors with COVID-19 incidence and death rates in the US. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2036462. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.36462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lee FC, Adams L, Graves SJ, et al. Counties with High COVID-19 Incidence and Relatively Large Racial and Ethnic Minority Populations - United States, April 1-December 22, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:483–9. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7013e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hatcher SM, Agnew-Brune C, Anderson M, et al. COVID-19 Among American Indian and Alaska Native Persons - 23 States, January 31-July 3, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1166–9. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6934e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Franco-Paredes C, Jankousky K, Schultz J, et al. COVID-19 in jails and prisons: a neglected infection in a marginalized population. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2020;14:e0008409. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Uscher-Pines L, Sousa J, Jones M, et al. Telehealth use among safety-net organizations in California during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA 2021;325:1106–7. 10.1001/jama.2021.0282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Corallo B, Tolbert J. Impact of coronavirus on community health centers, 2020. Available: https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/impact-of-coronavirus-on-community-health-centers/ [Accessed 17 Nov 2021].

- 43. Wright B, Fraher E, Holder MG, et al. Will community health centers survive COVID-19? J Rural Health 2021;37:235–8. 10.1111/jrh.12473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pathman DE, Goldberg L, Konrad TR. States’ Loan Repayment and Direct Financial Incentive Programs. Research Letter. JAMA 2013;310:1982–4. 10.1001/jama.2013.281644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rural Health Information Hub . Scholarships, loans, and loan repayment for rural health professions. Available: https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/scholarships-loans-loan-repayment [Accessed 19 Apr 2022].

- 46. Health Resources and Services Administration . National health service Corps: mission, work, and impact. Available: https://nhsc.hrsa.gov/about-us [Accessed 20 May 2022].

- 47. Pathman DE, Sonis J, Harrison JN, et al. Experiences of safety-net practice clinicians participating in the National health service Corps during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health Rep 2022;137:149-162. 10.1177/00333549211054083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Association of the American Medical Colleges . Loan Repayment/Forgiveness/Scholarship and other programs. Available: https://services.aamc.org/fed_loan_pub/index.cfm?fuseaction=public.welcome [Accessed 17 Nov 2021].

- 49. Pathman DE, Taylor DH, Konrad TR, et al. State scholarship, loan forgiveness, and related programs: the unheralded safety net. JAMA 2000;284:2084–92. 10.1001/jama.284.16.2084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. US Census Bureau . Population and housing state data, 2020. Available: https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/interactive/2020-population-and-housing-state-data.html

- 51. US Bureau of Economic Analysis . Personal income summary: personal income, population, per capita personal income, 2018. Available: https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?reqid=70&step=30&isuri=1&tableid=21&state=0&area=xx&year=2018,2017,2016,2015,2014&yearbegin=-1&13=70&area_type=0&11=-1&12=levels&3=non-industry&2=7&category=421&10=-1&1=20&0=720&year_end=-1&7=3&6=-1&5=xx,19000&4=4&classification=non-industry&9=19000&unit_of_measure=levels&8=20&statistic=3&major_area=0 [Accessed 17 Aug 2021].

- 52. Iowa Community Indicators Program . Urban percentage of the population for states, historical, 2010. Available: https://www.icip.iastate.edu/tables/population/urban-pct-states [Accessed 17 Aug 2021].

- 53. 3RNET . Provider retention and information system management (PriSM). Available: https://3RNET.org/PRISM [Accessed 17 Nov 2021].

- 54. Rauner T, Fannell J, Amundson M, et al. Partnering around data to address clinician retention in loan repayment programs: the Multistate/NHSC retention collaborative. J Rural Health 2015;31:231–4. 10.1111/jrh.12118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lamiani G, Borghi L, Argentero P. When healthcare professionals cannot do the right thing: A systematic review of moral distress and its correlates. J Health Psychol 2017;22:51–67. 10.1177/1359105315595120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Canadian Nurses Association . Code of ethics for registered nurses, 2017. Available: https://www.cna-aiic.ca/en/nursing/regulated-nursing-in-canada/nursing-ethics [Accessed 24 Apr 2022].

- 57. Hamric AB, Borchers CT, Epstein EG. Development and testing of an instrument to measure moral distress in healthcare professionals. AJOB Prim Res 2012;3:1–9. 10.1080/21507716.2011.652337 26137345 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Giannetta N, Villa G, Pennestrì F, et al. Instruments to assess moral distress among healthcare workers: a systematic review of measurement properties. Int J Nurs Stud 2020;111:1–34. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Epstein EG, Whitehead PB, Prompahakul C, et al. Enhancing understanding of moral distress: the measure of moral distress for health care professionals. AJOB Empir Bioeth 2019;10:113-124. 10.1080/23294515.2019.1586008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wocial LD, Weaver MT. Development and psychometric testing of a new tool for detecting moral distress: the moral distress thermometer. J Adv Nurs 2013;69:167–74. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06036.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Mehlis K, Bierwirth E, Laryionava K, et al. High prevalence of moral distress reported by oncologists and oncology nurses in end-of-life decision making. Psychooncology 2018;27:2733–9. 10.1002/pon.4868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Corley MC, Elswick RK, Gorman M, et al. Development and evaluation of a moral distress scale. J Adv Nurs 2001;33:250–6. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01658.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Peytchev A, Hill CA. Experiments in mobile web survey design. Soc Sci Comput Rev 2010;28:319–35. 10.1177/0894439309353037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64. JNK R, Scott AJ. On simple adjustments to chi-square tests with sample survey data. Ann Stat 1987;15:385–97. 10.1214/aos/1176350273 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Schreier M. Qualitative content analysis in practice. Sage Publications, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Saldaña J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. 2nd edn. Sage Publications, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 67. O’Connor C, Joffe H. Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: debates and practical guidelines. Int J Qual Methods 2020;19:1–13. 10.1177/1609406919899220 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Mays N, Pope C. Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ 2020;320:50–2. 10.1136/bmj.320.7226.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Maxwell JA. Using numbers in qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry 2010;16:475–82. 10.1177/1077800410364740 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Carminati L. Generalizability in qualitative research: a tale of two traditions. Qual Health Res 2018;28:2094–101. 10.1177/1049732318788379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Bree R, Gallagher G. Using Microsoft Excel to code and thematically analyse qualitative data: a simple, cost-effective approach. AISHE-J 2016;8:2811–21. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Schneider JN, Hiebel N, Kriegsmann-Rabe M, et al. Moral distress in hospitals during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: a web-based survey among 3,293 healthcare workers within the German network university medicine. Front Psychol 2021;12:775204. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.775204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. The Commonwealth Fund . The impact of COVID-19 on outpatient visits in 2020: visits remained stable, despite a late surge in cases, 2021. Available: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2021/feb/impactcovid-19-outpatient-visits-2020-visits-stable-despite-late-surge [Accessed 16 Jun 2022].

- 74. Kranz AM, Chen A, Gahlon G. Trends in dental office visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Dent Assoc 2020;2021:535–41. 10.1016/j.adaj.2021.02.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Zachrison KS, Yan Z, Schwamm LH. Changes in virtual and in-person health care utilization in a large health system during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2129973. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.29973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Jaworska A. Caring and full moral standing. Ethics 2007;117:460–97. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of biomedical Ethics.Eighth. 8th edn. Oxford University Press, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Jameton A. What moral distress in nursing history could suggest about the future of health care. AMA J Ethics 2017;19:617–28. 10.1001/journalofethics.2017.19.6.mhst1-1706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Maguen S, Price MA. Moral injury in the wake of coronavirus: attending to the psychological impact of the pandemic. Psychol Trauma 2020;12:S131–2. 10.1037/tra0000780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Shortland N, McGarry P, Merizalde J. Moral medical decision-making: colliding sacred values in response to COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Trauma 2020;12:S128–30. 10.1037/tra0000612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Luscombe R. Fauci: 100,000 new COVID deaths in US ‘predictable but preventable, 2021. The Guardian. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/aug/29/anthony-fauci-covid-deaths-vaccinations [Accessed 17 Nov 2021].

- 82. McAndrew NS, Leske J, Schroeter K. Moral distress in critical care nursing: the state of the science. Nurs Ethics 2018;25:552–70. 10.1177/0969733016664975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Young KP, Kolcz DL, O'Sullivan DM, et al. Health care workers' mental health and quality of life during COVID-19: results from a Mid-Pandemic, national survey. Psychiatr Serv 2021;72:122–8. 10.1176/appi.ps.202000424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Fish JN, Mittal M. Mental Health Providers During COVID-19 : Essential to the US Public Health Workforce and in Need of Support. Public Health Rep 2021;136:14–17. 10.1177/0033354920965266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Baptista S, Teixeira A, Castro L, et al. Physician burnout in primary care during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study in Portugal. J Prim Care Community Health 2021;12:21501327211008437. 10.1177/21501327211008437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Magill E, Siegel Z, Pike KM. The mental health of frontline health care providers during pandemics: a rapid review of the literature. Psychiatr Serv 2020;71:1260–9. 10.1176/appi.ps.202000274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]