Abstract

Background

With rising rates of atherosclerotic disease and obesity worldwide, the prevalence of chronic mesenteric ischemia (CMI) has been progressively rising. Prompt diagnosis and early intervention are crucial to avoid bowel loss and mortality in optimising long-term outcomes for patients and achieving symptom relief.

Objectives

This article aims to summarise relevant literature on CMI, enabling primary care physicians to make a timely diagnosis and intervention, improving outcomes of patients with CMI.

Discussion

CMI is often mistaken for more common pathologies due to its non-specific history and physical examination findings. A missed diagnosis can end up in acute mesenteric infarction and bowel perforation which can cause severe morbidity and mortality. Thus, a thorough gastrointestinal disease work-up ruling out other conditions may be required. CT angiogram is the gold standard non-invasive investigation for confirming a CMI diagnosis. Referral to vascular surgery with early surgical intervention through angioplasty and stenting is crucial for improving patient outcomes. Long-term follow-up of patients through routine consultations and serial non-invasive imaging can monitor for recurrence and disease progression.

1. Aim

1.1. Body

1.1.1. Terminology & classification

The terminology used to reference the spectrum of disease associated with chronic mesenteric ischemia (CMI) is commonly miscited. Mesenteric ischemia can be either acute or chronic [1]. Acute mesenteric ischemia (AMI) is sudden onset intestinal hypoperfusion due to either arterial thrombosis or embolism. It can be de novo or in the background of CMI [1]. Contrarily, CMI is a progressive degeneration of vessels of the small intestine typically over years [1]. Due to its temporal chronicity, collateral circulation often develops in CMI to compensate for hypoperfusion, although symptoms arise when there is inadequate collateral circulation [2]. Note that CMI is pathologically discrete from colonic ischemia which is transient hypoperfusion of the large intestine at ‘watershed’ areas namely the splenic flexure and the rectosigmoid junction [2]. In practice, most symptomatic patients present with multivessel mesenteric stenosis with features of both CMI and colonic ischemia [2].

1.1.2. Aetiology

Similarly to the pathophysiology of peripheral artery disease (PAD) and stable angina, CMI is caused by insufficient gastrointestinal blood supply, via the celiac artery or superior mesenteric artery, to the small intestine during periods of increased vascular demand. The prevalence of mesenteric atherosclerosis reportedly ranges from 6 to 29%, although only a minority develop ischemia and consequently CMI³. Postprandially, functional hyperaemia occurs in response to food consumption, proposed to be mediated by cholinergic modulation[3]. Celiac artery blood flow rises earlier (5 min ±1 min) and is transient, whereas superior mesenteric artery (SMA) blood flow increases later (41 ± 4 min) and is more prolonged[4]. Lipid and protein-rich foods have been associated with greater hyperaemia and thus, greater pain in patients with CMI³.

1.1.3. Presentation

Demographically, CMI commonly presents in elderly (>65years) females with atherosclerotic risk factors such as smoking, diabetes, obesity, high-fat diets and low levels of physical activity[5]. Patients may have a history of atherosclerotic disease sequelae such as myocardial infarction, stroke, carotid stenosis, and PAD.

The classic triad of symptoms is a combination of postprandial pain, significant weight loss and abdominal bruit, although all three co-exist in only 20% of CMI patients[6]. Other atypical presenting signs include diarrhoea, nausea, vomiting, occult gastrointestinal bleeding, or constipation⁷. Physical examination findings are often non-specific. Signs of cachexia, presence of abdominal bruits (17–87% of cases), and diminished peripheral pulses are suggestive of generalized arterial occlusion [8,9].

1.1.4. Diagnostics and work-up

Understandably, the non-specific signs of CMI may be commonly presumed to be caused by more commonplace pathologies such as malignancy, chronic cholecystitis, peptic ulcer disease, chronic pancreatitis, or inflammatory bowel disease [10]. Unless the patient clinical history and examination are unequivocal, most patients should undergo an extensive gastrointestinal disease workup for maladies of higher prevalence prior to screening for CMI as outlined in Table 110.

Table 1.

Possible investigations for patients with signs indicating low-moderate suspicion of CMI. N.B. Investigations chosen should be tailored based on individual patient presentations.

| Investigation | Indication |

|---|---|

| Full Blood Count | Anaemia, hypercholesterolemia |

| Urease breath test | H.pylori infection in peptic ulcer disease |

| Urine & Electrolytes | Electrolyte derangements caused by chronic diarrhoea |

| FOBT | Triaging for elective colonoscopy |

| USS Abdomen | To exclude Gallstone disease and Chronic Pancreatitis |

| CT Abdomen and pelvis | To exclude malignancy and other chronic diseases |

| Colonoscopy | Malignancy |

Possible work-up investigations may include:

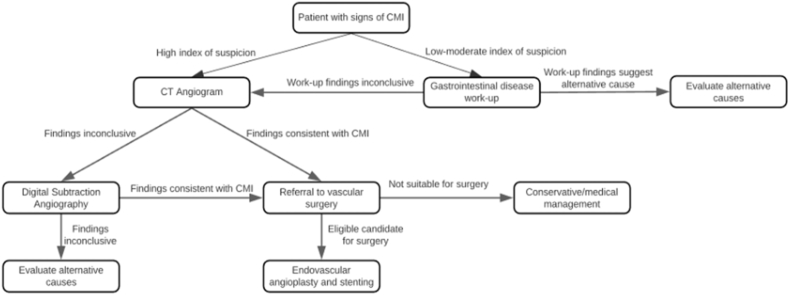

Following initial gastrointestinal disease work-up, patients should be further investigated with specific testing (Fig. 1). For patients with a high degree of clinical suspicion of CMI or non-conclusive gastrointestinal workup findings, CT angiography (CTA) (100% sensitivity, 95% specificity) or duplex ultrasound (DUS) imaging (72–100% sensitivity, 77–90% specificity) should be considered [8]. CTA is the preferred diagnostic approach, although contraindicated in pregnancy and patients with contrast allergy or low eGFR (<30 mL/min/1.73 m [2]). Arterial digital subtraction angiography (DSA) is the gold standard diagnostic tool for CMI when non-invasive techniques such as CTA and DUS are equivocal [9].

Fig. 1.

Approach to investigations and treatment for chronic mesenteric ischemia.

1.1.5. Treatment & outcomes

Once CMI is diagnostically confirmed, a referral to vascular surgery should be organised [7].

For non-surgical candidates receiving conservative therapy, antiplatelet therapy and commencement of statins are recommended [7]. Although, the benefits of dual antiplatelets compared with monotherapy is still ambiguous [7]. Patients undertaking conservative management require careful monitoring for acute deterioration and worsening of existing symptoms. For these patients, a low threshold is recommended for proceeding with surgery on a patient-by-patient basis.

For surgical candidates, prompt surgical intervention is crucial with untreated symptomatic CMI carrying 5-year mortality rates approaching 100% [11,12]. Historically, open revascularisation approaches were trialled, although endovascular approaches have been associated with lower rates of in-hospital cardiac and cerebrovascular events, lower admission durations and fewer composite in-hospital complications [7,10,13]. Surgical outcomes of endovascular treatment are positive with 86–96% of patients maintaining symptom relief at 5–10 years [14]. Re-stenosis may occur in up to 40% of patients, thus requiring re-intervention [9]. Following revascularisation, patients may resume regular diet [7].

The primary goals of intervention for patients with CMI are achieving symptom relief, restoring normal BMI, and preventing bowel infarction. Primary care physicians should provide all CMI patients with education regarding thrombotic risk factors such as diabetes, tobacco, hypertension, high-fat diet, and low physical activity. Follow-up of patients that are managed either conservatively or surgically is essential for optimising patient outcomes. These include regular consultations and serial non-invasive imaging to monitor for re-stenosis or symptom re-occurrence. The recommended imaging modality is duplex ultrasound obtained at 3–6 monthly intervals [15].

2. Conclusion

Chronic mesenteric ischemia (CMI), or intestinal angina, is abdominal pain caused by reduced visceral perfusion of the small intestine due to atherosclerosis. If untreated, long-term complications include severe weight loss or malnutrition and rarely transformation to acute mesenteric ischemia contributing to bowel loss.

Information regarding the prevalence and optimal management guidelines are dynamic due to the novelty of CMI as a diagnosis. Further research through ongoing randomised controlled trials and developing literature can provide greater direction for general practitioners to practice evidence-based medicine.

Ethical approval

Given the nature of the people not involving direct patient contact, no ethics approval was required for this paper.

Sources of funding

There were no sources of funding for this research.

Author contribution

Aathavan Shanmuga Anandan (MD4): manuscript curation, table/figure creation, referencing, journal submission preparation, Dr. Munasinghe Silva: thesis generation, manuscript curation, proofreading.

Registration of research studies

As research did not involve human participants, registration of research was not required.

Guarantor

I, Aathavan Shanmuga Anandan, am the guarantor for this paper and accept full responsibility for the work and/or the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Consent

Given the absence of any patient involvement, consent was not required for this paper.

Declaration of competing interest

There are no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Goodman E. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences; 1918. Angina Abdominis; pp. 524–528. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hansen K., Wilson D., Craven T., Pearce J., English W., Edwards M.…Burke G. Mesenteric artery disease in the elderly. J. Vasc. Surg. 2004:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahajan K., Osueni A., Haseeb M. StatPearls Publishing; Florida: 2021. Abdominal Angina. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poole J., Sammartano R., Boley S. Hemodynamic basis of the pain of chronic mesenteric lschemia. Am. J. Surg. 1987:171–176. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(87)90809-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Dijk L., van Noord D., de Vries A., Kolkman J., Geelkerken R., Verhagen H.…Bruno M. United European Gastroenterology Journal; 2018. Clinical Management of Chronic Mesenteric Ischemia; pp. 179–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herbert G., Steele S. Surgical Clinics of North America; 2007. Acute and Chronic Mesenteric Ischemia; pp. 1115–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kvietys P. Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences; California: 2020. The Gastrointestinal Circulation. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Someya N., Endo M., Fukuba Y., Hayashi N. Blood flow responses in celiac and superior mesenteric arteries in the initial phase of digestion. Am. J. Physiol. 2008:1790–1796. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00553.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hohenwalter E. Chronic mesenteric ischemia: diagnosis and treatment. Semin. Intervent. Radiol. 2009:345–351. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1242198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sana A., Vergouwe Y., Noord D., Moons L., Pattynama P., Verhagen H.…Mensink P. Radiological imaging and gastrointestinal tonometry add value in diagnosis of chronic gastrointestinal ischemia. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011:234–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bjorck M., Koelemay M., Acosta S., Goncalves K.T., Kolkman J., Lees T.L.…Verzini F. Editor's choice - management of the diseases of mesenteric arteries and veins: clinical practice guidelines of the European society of vascular surgery (ESVS) Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2017:460–510. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2017.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moawad J., Gewertz B. The Archives of Surgery; 1997. Chronic Mesenteric Ischemia; pp. 618–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patel R., Waheed A., Costanza M. Treasure Island; StatPearls: 2021. Chronic Mesenteric Ischemia. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pillai A., Kalva S., Hsu S., Walker G., Silberzweig J., Annamalai G.B.…Dariushnia S. Quality improvement guidelines for mesenteric angioplasty and stent placement for the treatment of chronic mesenteric ischemia. J. Vasc. Intervent. Radiol. 2018:642–647. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2017.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alahdab F., Arwani R., Pasha A., Razouki Z., Prokop L., Huber T., Murad H. A systematic review and meta-analysis of endovascular versus open surgical revascularization for chronic mesenteric ischemia. J. Vasc. Surg. 2018:1598–1605. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2017.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]