Abstract

To enhance health and medical facilities, some authorities have recently introduced an emergency special water vehicle known as a ‘water ambulance’. This vehicle is distinct for remote areas. To operate the ambulance service, environmental issues and energy resources have become major concerns. This is a scope of research to address the issues. First, the possibility of using solar energy as the sole power source for a vessel is a perfect solution to these issues. Second, solar vessels operate everywhere without polluting the environment. In addition, another contribution of the research is to integrate a control unit in a water ambulance which is called an ‘intelligent unit’. This unit will prioritize the source of energy to ensure uninterrupted power to emergency medical equipment and ambulances. This paper proposes a dynamic design of a solar water ambulance that is subject to replacing small conventional fuel-run watercraft vehicles.

Keywords: Smart solar, ICU, Solar water ambulance, Recue, Solar system

Highlights

-

•

Usage of solar energy as the power source for a Solar ICU water ambulance is a perfect solution to meet power crisis.

-

•

Solar water ambulance operates everywhere without polluting the environment.

-

•

Another feature of the research is to integrate a control unit in a water ambulance which is called an ‘intelligent unit’.

-

•

An algorithm is developed for ‘intelligent unit’. This intelligent unit will prioritize the source of energy to ensure uninterrupted power to emergency medical equipment and ambulances.

-

•

Dynamic analysis of a solar ICU water ambulance has been developed in this research.

1. Introduction

Developing a water ambulance that is run by solar power would be a great contribution. This demand arises from the awareness that protecting the environment of waterways is a major issue in certain areas of the world. With this positive growth from a medical perspective, the potential development of a water vehicle that works on clean energy has emerged. Patients in each and every corner of the country can now avail of the services of a water ambulance in times of need. This proposed design will be a proper reference for designing a solar ambulance, where the application range would vary from small to big vessels for medical purposes. There are some remote areas that are surrounded by rivers. Owing to the lack of an equipping hospital in the village, people living here have to use the river to get to medical centres in other places. Water ambulances; have begun a new ambulance service in the area. The boat ambulance can reach patients within 24 h and take them to the nearest headquarters hospital within minutes. It is armed with medical facilities such as oxygen and emergency medicine. Water ambulance currently operate in remote areas with conventional fuel [1]. But this could be an environmental issue. This project allowed the researcher to develop a system to address this newly created challenge. This research developed a solar-run water ambulance, resulting in no need to think about refilling with fuel in remote areas or having environmental issues due to conventional fuel.

There are some gaps in previous research. In this paper some innovation is introduced to minimize the gap. A programmable unit named an ‘‘intelligent unit’ is integrated in this ambulance. This unit ensures an uninterrupted power supply. The first priority is solar as a source of energy [2]. Solar runs some auxiliaries of the ambulance such as security lights, air cooling systems etc., and, most importantly, emergency medical equipment. If solar energy system fails to run, the unit ensures an alternate source as energy. Additionally, this intelligent unit is connected to the central data base of the health directorate. In times of severe condition, expert doctors can be connected directly to the ambulance for online treatment. Onboard authorized doctors will be assisted by online expert doctors. All ICUs in the country are also interlocked with this unit. This unit also indicates the nearest vacant ICU to the ambulance. This intelligent unit itself can diagnose and solve some troubles with the ambulance. Technology experts continuously monitor all technical specifications of the ambulance through this unit. Full-time health and expert workers will maintain the ambulance. The ambulances are to go under regular diagnosis for trouble shooting.

2. Materials and methods

Compared with the traditional propulsion system, the water ambulance intelligent solar system has many advantages and economic benefits in ambulance design, propulsion performance, manufacturing and maintenance [3]. It has a high promotion value in many water ambulances and commercial ships compared with traditional ships. The project uses windsurfing and photovoltaic technology to provide green energy for ambulance's travel. It has a high promotional value in the waters of urban reservoir areas [4]. When the sail is assisted, the windward angle of attack is adaptive, and the maximum beneficial windward area is maintained at any time to achieve the purpose of assisting the ambulance. When the light energy utilization effect is good, the photovoltaic power generation area is expanded by the wind and light conversion device. The angular adaptive control system controls the sail to automatically turn to the maximum face-up surface, increasing its power generation efficiency, thereby achieving the purpose of propelling the cruise ambulance [5,6]. Compared with traditional electric cruise ambulance s, a rough estimate can increase endurance by 60% and maximum speed by 30%. The energy acquired by the ambulance intelligent solar system and the way it is acquired are clean and pollution free. With the increasing requirements of international laws and regulations on the greening of ambulances, the effective use of clean ocean energy can reduce the discharge of pollutants from ambulances [7] make full use of natural resources, reduce energy consumption, and save costs. It also avoids the risk of polluting urban waters after an ambulance accident. In addition, this solar energy system can be improved to provide auxiliary power and daily electricity for more ambulance types [8]. Electrical power supply is a crucial element in the success and quality of EMS cares [9]. Nearly all ambulance components rely on electricity to function. These components include all ambulance lights, communication systems, rescue equipment, and temperature control units.

2.1. Components of the system

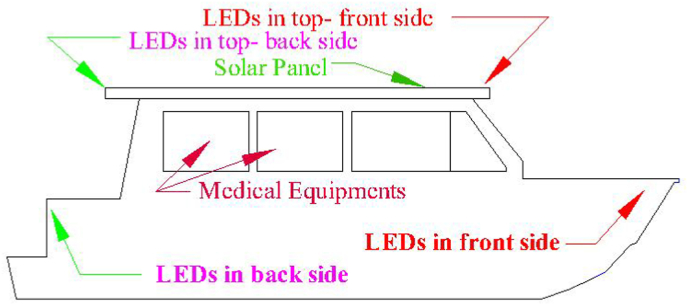

There are some basic components of solar water ambulances. A solar panel converts solar energy into electrical energy. The charge controller (Fig. 1) controls the output and safety of the system.

Fig. 1.

Controller of the solar energy system.

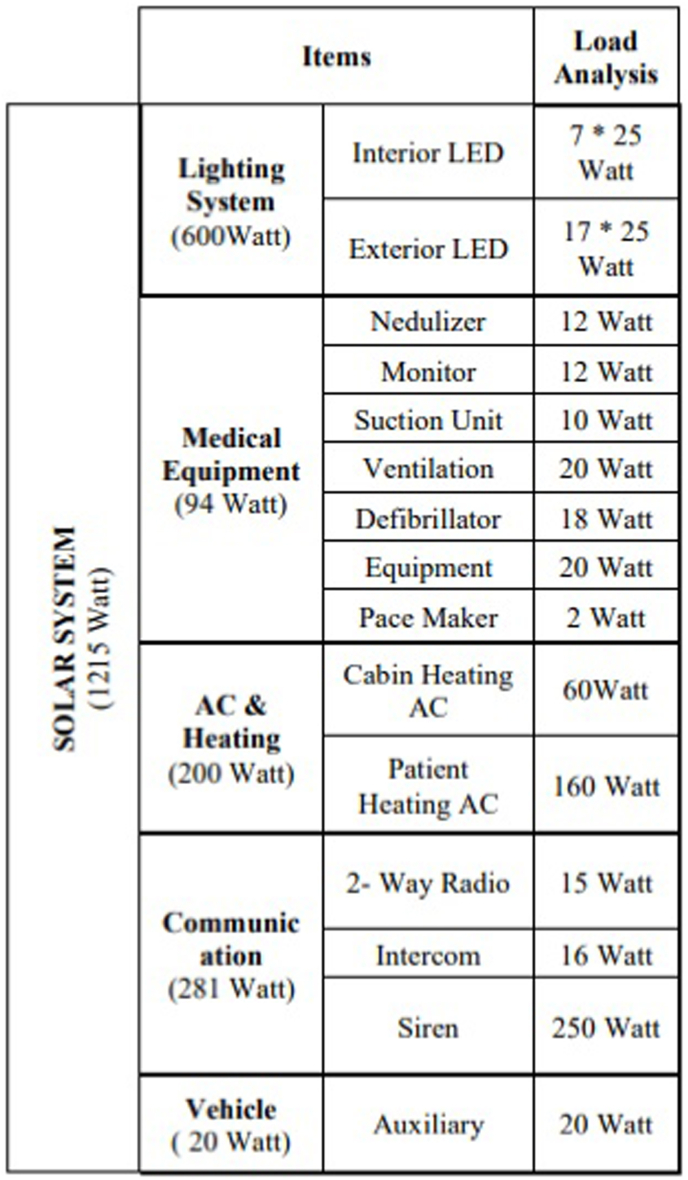

In some circumstances, a patient receiving care may require the use of several medical devices, a variety of lighting instruments, and some form of temperature control running all at the same time [10]. Therefore, by individually detailing each form of power consumption and obtaining its electrical requirements, we provide the necessary information to analyse the ambulances total power consumption [11]. To further understand the power consumed within an ambulance a general breakdown of the primary components used in each of these categories can be seen in Fig. 2. The lighting component includes interior lights for the patient compartment as well as for the driver's cabin, while the outdoor headlights include emergency headlights and standard ambulance headlights [12]. Communication can be broken down into the exterior public siren, ambulance intercom system, and two-way radio used to communicate with other ambulances and base. Temperature control is divided into heating, cooling, and ventilation for both the patient and driver's cabin [13] (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

Details of medical component list with load analysis.

Fig. 4.

Flow chart of the mechanism of the system.

2.2. Load Analysis

Finally, a ramification of scientific medical equipment or gadgets is powered using either patient bay outlets or outside outlets. The breakdown of power consumers within an ambulance leads to a further detailed, numerical representation to visually see the distribution of power [14,15].

2.3. Details of the design

In an attempt to safely manage the power needed to supply all the necessary lifesaving rescue equipment, the total power consumption, in Watts, was compiled. In order to compile all the information for this chart, each device and light were individually analysed [[16], [17], [18]].

2.4. Electrical system

An ambulance has several different configurations that generate, supply, and distribute electrical power to all of an ambulance's components (Fig. 3). These systems include the battery, 12 V DC electrical systems, and 125 V AC systems [[19], [20], [21]]. Each of these is utilised in different ways to effectively power the lights, temperature control, and rescue equipment. Additionally, they all have specific criteria based on the latest NFPA 2017 standards [[22], [23], [24]]. Understanding how these systems distribute power and the guidelines that govern them are important when considering the integration of a new power system. The remainder of this section will introduce the notable aspects of each system and clarify which electrical components within an ambulance rely on which system for operation [[25], [26], [27]].

Fig. 3.

Water ambulance design.

2.5. Rescue equipment

All ambulances have a standard set of equipment (Fig. 2) that must be onboard [[28], [[29], [30]]. This list was established after the Committee on Trauma (COT), the American College of Surgeons (ACS), and the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) collaborated and created a joint document in 2000. This list was later revised by the National Association of EMS Physicians (NAEMSP) in 2005. This list of equipment can be broken down into the following categories: Basic Life Support (BLS) Ambulances, Advanced Life Support (ALS) Ambulances, and optional equipment [31].

2.6. Communication system

All ambulances have stern radio provisions. Ambulances must be provided with sufficient ventilated space for a two-way radio, which includes convenience features, antenna openings, ground plane, and terminal wiring for 12-V power and ground [32,33].

2.7. Lighting – interior and exterior

Considered one of an ambulance's maximum great capabilities and important power consumers is its big array of lighting fixtures [34,35]. Whether or not it is the emergency lighting fixture system, trendy midnight headlights, or indoors affected person cabin lighting fixtures, lighting fixtures prove to be an indispensable component of this project's attention.

2.8. Air conditioning

Specifically, the engine should start without the use of external power or starting fluids. The heater in each compartment should raise the thermocouple temperature to a minimum of 68 °F (24 °C) within 30 min from 0 °F (−18 °C) [36].

3. Results

There are some improvements to our project compared to previous relative projects. Programmable logic is used here to operate the ambulance. Flow charts and corresponding coding are mentioned here. This makes the research unique.

Logic-1 (Energy Priority):

Coding for the mechanism of the system.

3.1. Design of intelligent unit

The main innovation of this solar-run water ambulance to optimum energy consumption in an efficient way is this ‘intelligent unit’. The whole water ambulance will be controlled by this unit. When, solar is available, this unit will operate the ambulance's total system of the ambulance with solar energy [37]. However, the main priority is medical equipment. If solar is not available then next suitable source will be activated like battery or diesel. Dynamic logic control is storied inside the unit. The display and control panel are outside of the panel. The full control system is on this screen (Fig. 5). Total consumption, available energy, and everything is seen on this screen.

Fig. 5.

Design of intelligent unit of water ambulance.

As it is new age of environmentally friendly technology, while maximizing efficiency, it is important to reduce the burden on the environment [[38], [39], [40]]. By implementing the methods of improvement, the proposed medical ambulances will provide numerous benefits in mobile healthcare and accident survival rates, while reducing carbon emissions and saving energy (Fig. 6). By looking through each specific category of energy consuming devices onboard an ambulance, a complete understanding of the electrical systems involved was developed [41,42]. These categories were broken down further to investigate the purposes of each component and the role they play in mobile medical emergencies. By analysing power consumption with regards to importance and applicability in emergency situations, the most vital components were separated from those that are not as critical. Following this, suggestions were made on preventing power failure in aspects of operation that are most critical. The initial investment in solar water ambulances is higher than for conventional ambulances but after that, the rest of the operational life cycle of a solar water ambulance has less operational costs than the conventional ambulance.

Fig. 6.

Final steps of the intelligent solar ICU water ambulance.

After understanding how the production and consumption of electrical systems function, the development of innovative solutions can be implemented. Using solutions to increase production or reduce consumption, a model for a more efficient and effective ambulance could be established. By researching various options to complete this task, it has become clear that some options are more suitable than others [43]. The balance of applicability, ease of implementation, cost, effectiveness, practicality, and necessity had to be considered, while deciding which systems would be most appropriate. A comparative study was conducted on the ambulance's power consumption and power production. The power output was researched and presented in detail, to obtain suggestions for the distribution of power. The typical ambulance power system was termed obsolete, and archaic, considering the numerous alternative options available.

4. Conclusions

The design of a solar water ambulance for patient delivery alongside the coast, inside the rivers, and within the lakes has been presented. With this research, it is quite possible to replace the standard conventional engine with an electric one, by accepting loss in electricity, and without converting the load and the size of the boat. This is a great achievement. This water ambulance has more prices in assessment than an equal boat geared up with traditional propulsion. Currently there are greater prices for manufacturing water ambulances because of photovoltaic plants, battery installations and control devices. However, there are still some findings as to why conventional ambulances should be replaced by this type of ambulance. Above additional expenses are partially compensated with the aid of discount of operation prices; in a water ambulance there may be no intake of gas, and the maintenances fees are fantastically decreased. In water ambulances, the initial extra price is also very low. In addition, the high-quality gain of using renewable energy produces oblique socio-financial benefits; eco machine protection, reduction of co2, nox, and sox emissions, etc. In this paper, we propose a modern solar water ambulance. In this study, the solar energy system was optimized. The designed ambulance contributes zero pollution and has very low going for walk costs; all of the vital energy for navigation has renewable origins. Energy produced by using photovoltaics is more secure and more environmentally benign than traditional energy resources. However, there are environmental, safety, and health problems associated with manufacturing, using, and eliminating photovoltaic devices. The production of electronic equipment is extensive. The power produced is higher than the one important to manufacture the photovoltaic modules and the energy destroy-even point is generally reached in a period of three to six years. This developed water ambulance should be practiced immediately in this industry.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.

Sources of funding

Self-Funded

Ethical approval

Research is no concerned with a specific patient. It is research about technology of treatment.

Consent

Not required as research is no concerned with a specific patient. It is research about technology of treatment.

Author contribution

Author: Tawheed Hasan-

(Experiment, study concept, design, data collection, data analysis, writing the paper etc).

Co-Authors:

i. Dr. Shahrizan Jamaludin,

ii. Prof. Dr. WB Wan Nik.

Supervisors of this research, who guided the research directly.

Contributors: Prof. Dr. Rizwan Khan.

Co- Supervisor of this research, who is also assisting the practical experiments.

Registration of research studies

-

1.

Name of the registry: NOT APPLICABLE AS, NOT HUMAN STUDY

-

2.

Unique Identifying number or registration ID:

-

3.

Hyperlink to your specific registration (must be publicly accessible and will be checked):

Guarantor

Tawheed Hasan-

Dr. Shahrizan Jamaludin.

Prof. Dr. WB Wan Nik.

Declaration of competing interest

Authors do not have any conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Dominic D. The Mattingley Publishing Co., Inc; 2018. Renewable Energy Will Be Consistently Cheaper than Fossil Fuels by 2020, Report Claims”, Forbes. November-December 2019 , ISSN: 0193-4120 Page No. 5994 - 6001 6001, Published by. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rifai T., Solheim E., Espinosa P. United Nations Environment Programme; 2017. Let's Make All Tourism Green and Clean”. [Online], Available: [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson Cadie. Business Insider; Jun 4, 2017. This Sleek-Looking Electric Yacht Is Powered by the Sun.https://www.businessinsider.com/soelcat-12-electric-yacht-solar-powered-2017-5/ [Online], Available: [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Castro Nóbrega Juraci Carlos, Rössling Andrej. Development of solar powered boat for maximum energy efficiency. International Conference on Renewable Energies and Power Quality(ICREPQ’12)Santiago de Compostela (Spain) 2012;1(10) 28th to 30th March. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wyman M., Barborak J.R., Inamdar N., Stein T. Best practices for tourism concessions in protected areas: a review of the field. Forests. 2011;2(4):913–928. doi: 10.3390/f2040913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davenport J., Davenport J.L. The impact of tourism and personal leisure transport on coastal environments: a review estuarine. Coastal and Shelf Science. 2006;67(1- 2):280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2005.11.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soto J.L.F., Seijo R.G., Formoso J.A., Iglesias G., Couce L.C. Alternative sources of energy in shipping. J. Navig. 2010;63(1–2):435–448. doi: 10.1017/S0373463310000111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schirripa Spagnolo Giuseppe, Papalillo Donato, Martocchia Andrea, Makary Giuseppe. Solar-electric boat. J. Transport. Technol. April 23, 2012;2(2) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sudhoff S.D. Currents of change electric ship propulsion systems. IEEE Power Energy Mag. 2011;9(4):30–37. doi: 10.1109/MPE.2011.941319. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spagnolo G. Schirripa, Papalillo D., Martocchia A. Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering; Rome: 2011. Eco Friendly Electric Propulsion Boat,” 10th International; pp. 1–4. 8-11 May. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weidong X., Ozog N., Dunford W.G. Topology study of photovoltaic interface for maximum power point tracking. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2007;42(3):1696–1704. doi: 10.1109/TIE.2007.894732. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang C., Chen W., Shao S., Chen Z., Zhu B., Li H. Energy management of stand-alone hybrid PV sys-tem. Energy Proc. 2011;12:471–479. doi: 10.1016/j.egypro.2011.10.063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hassenzahl David M., Hager Mary Catherine, Berg Linda R. Wiley in Collaboration with the National Geographic Society; Hoboken, NJ: 2016. Visualizing Environmental Science. 2007. Print. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Effraimidis Daniil, Fournier Nathan, Jennings Brian, Perruccio Michael. Improving ambulance power systems. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.464.7222&rep=rep1&type=pdf April 30, 2013, Project Number: MQF-IQP-2125, [Online], Available.

- 15.Rashid Hussain, Sharma Sandhya, Sharma Vinita. Automated intelligent traffic control system quality. Using sensors. IJSCE ISSN. 2013;3(3):2231–2307. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scholand Michael, E Dillon Heather. US Department of Energy; August 2012. Life-Cycle Assessment of Energy and Environmental Impacts of LED Lighting Products”. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Timothy Z. Automotive LED lighting explained. What Car? 19, March 2012 https://www.carid.com/articles/automotive-led-lighting-explained.html [Online], Available. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yosef Khalil M., Jamal N., Ali M. Intelligent Traffic light flow control system using wireless sensor. IEEE journal of information science and engineering. 2010;26:753–768. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lakatos L., Hevessy G., Kovács J. Advantages and disadvantages of solar energy and wind- power utilization. World Futures. 2011;67(6):395–408. doi: 10.1080/02604020903021776. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh Rajendra, Francis Alapatt Githin, Lakhtakia Akhlesh. Making solar cells a reality in every home: opportunities and challenges for photovoltaic device design. IEEE Journal Of The Electron Devices Society. June 2013;1(6) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bagher Askari Mohammad, Abadi Vahid Mirzaei Mahmoud, Mohsen Mirhabibi. Types of solar cells and application. Am. J. Opt. Photon. 2015;3(5):94–113. 2330-8486 (Print) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paul Starkey, Ellis Simon, John Hine, Anna Ternell. World Bank; Washington, DC: 2002. Improving Rural Mobility : Options for Developing Motorized and Nonmotorized Transport in Rural Areas. World Bank Technical Paper; No. 525. [Online], Available. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Begum S., Sen B. 2004. (Unsustainable livelihoods health shocksand urban chronic poverty: rickshaw pullers as a case study). Chronic Poverty Research Centre Working Paper 46. [Online], Available: [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faraz T., Azad A. Global Humanitarian Technology Conference (GHTC) 2012 IEEE. 2012. Solar battery charging station and Torque sensor based electrically assisted rickshaw; pp. 12–22. 21-24 Oct. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khan F.R., Aurony A.T., Rahman A., Munira F., Halim N., Azad A. Torque sensor based electrically assisted hybrid rickshaw- van with PV assistance and solar battery charging station. 3rd International Conference on Advances in Electrical Engineering (ICAEE) December 2015:17–19. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chowdhury S.J., Rahman R., Azad A. Power conversion for environment friendly electrically assisted rickshaw using photovoltaic technology in Bangladesh. Transportation Electrification Conference and Expo (ITEC) 2015 IEEE. 14-17 June 2015:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Islam M.Z., Shameem R., Mashsharat A., Mim M.S., Rafy M.F., Pervej M.S., Ahad M.A.R. A study of solar home system in Bangladesh: current status, future prospect and constraints. 2nd International Conference on Green Energy and Technology, Dhaka, Bangladesh. 5-6 September 2014:110–115. doi: 10.1109/ICGET.2014.6966674. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Masud M.H., Nuruzzaman M., Ahamed R., Ananno A.A., Tomal A.N.M.A. Renewable energy in Bangladesh: current situation and future prospect. Int. J. Sustain. Energy. 2020;39:132–175. doi: 10.1080/14786451.2019.1659270. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [29.Chris Hendrickson, Deanna H. Matthews, M Ashe, Paulina Jaramillo, “Reducing environmental burdens of solid- state lighting through end-of-life design”, IOP Science, February 2010, Environmental Research Letters 5(1):014016, DOI:10.1088/1748-9326/5/1/014016.

- 30.Cleveland Cutler J. vol. 6. Elsevier; 2007. History of wind energy; pp. 421–422. (Encyclopedia of Energy). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Razo Victor del, Jacobsen Hans-Arno. Vehicle- originating- signals for real-time charging control of electric vehicle fleets. IEEE Transactions On Transportation Electrification. August 2015;1(2) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumari Alisaa, Ranjan Ankita, Srivastava Shivangi. Solar powered vehicle", international journal of electronics, electrical and computational system. IJEECS. May 2014;3(3) ISSN 2348-117X. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jain Shivani, Tiwari Neha. Grid solar hybrid speed controller for electric vehicle – a working model. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. January 2015;3(1) ISSN (Online): 2347-3878. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Melot Julien, Marine Earth” Azura. The awesome foundation. 2016. https://www.awesomefoundation.org/en/projects/71911-azura-marine-earth [Online], Available.

- 35.Thompson Cadie. INSIDER; Jun 4, 2017. This Sleek-Looking Electric Yacht Is Powered by the Sun.https://www.businessinsider.com/soelcat-12-electric-yacht-solar-powered-2017-5 [Online], Available: [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kurniawan A. A review of solar-powered boat development. Journal for Technology and Science. 2016;27(1):1–8. http://www.iptek.its.ac.id/index.php/jts/article/view/761 [Online], Available: [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salem A., Seddiek I.S. Techno-economic approach to solar energy systems onboard marine vehicles, polish maritime research. Pol. Marit. Res. October 2016;23(91):64–71. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kurniawan Adi. A review of solar-powered boat development. IPTEK Journal of Science and Technology. 2016;27(1) doi: 10.12962/j20882033.v27i1.761. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tukaram S., Uttam S.R., Shivaji R.S., Ankush N.R., Kare K.M. Design and fabrication of A solar boat. ” International Journal of Innovation in Engineering Research and Technology. 2016;3(1):1–4. https://www.ijiert.org/download file?file=1453195178_Volume%203%20Issue%201.pdf Available. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mahmud K., Morsalin S., Khan I. Design and fabrication of an automated solar boat. International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology. 2014;64:31–42. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Han J., Charpentier J.F., Tang T. An energy management system of a fuel cell/battery hybrid boat. Energies. 2014;7:2799–2820. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hua J., Wu Y.H., Jin P.F. Prospects for renewable energy for seaborne transportation—Taiwan example. Renew. Energy. 2008;33(5):1056–1063. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glykas A., Papaioannou G., Perissakis S. Application and cost–benefit analysis of solar hybrid power installation on merchant marine vessel. Ocean Eng. 2010;37(7):592–602. [Google Scholar]