Abstract

A novel sequence of 2.9 kb in the intergenic region between the mutS and rpoS genes of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and closely related strains replaces a sequence of 6.1 kb in E. coli K-12 strains. At the same locus in Shigella dysenteriae type 1, a sequence identical to that in O157:H7 is bounded by the IS1 insertion sequence element. Extensive polymorphism in the mutS-rpoS chromosomal region is indicative of horizontal transfer events.

How Escherichia coli O157:H7 evolved is a subject whose interest spans clinical medicine, food safety research, and evolutionary biology. This enterohemorrhagic E. coli strain was first recognized as a human pathogen in 1982 (22). It has since risen to prominence as a cause of major outbreaks of food-related disease worldwide. In a recent example, a single outbreak in Japan in 1996 (23) accounted for over 5,000 illnesses and six deaths. In the United States, E. coli O157:H7 is responsible for an estimated 20,000 cases of food-borne disease annually (7). The recognition that beef products were sources of E. coli O157:H7 contamination (22) and the identification of healthy dairy cattle as one reservoir for the organism (15) implicated a cattle-to-human zoonosis. Clonal analysis supports the thesis that O157:H7 evolved recently from a lineage of E. coli that lived as a commensal organism in animals (25). This versatile enteric organism has adapted to other environments as well, as it is known to survive conditions of low pH (1) or high salt and temperature (12) that formerly safeguarded the food supply from E. coli contamination.

The availability of the entire nucleotide sequence of E. coli MG1655 (4), a representative of laboratory-attenuated E. coli K-12 strains, makes possible a formal comparison with E. coli O157:H7 sequences as they become available. The quest of a comparative genomic approach is to identify the types and sources of genetic variability and to delimit unique sequences that contribute to important phenotypes within a particular organism. Such information should be useful in understanding the pathogenicity of O157:H7 and its ability to adapt to unconventional environments. Moreover, evolutionary artifacts, the remnants of sequences left within the genome from past genetic transgressions, provide valuable insights into the genesis and evolution of E. coli O157:H7.

E. coli O157:H7 mutS-rpoS intergenic region.

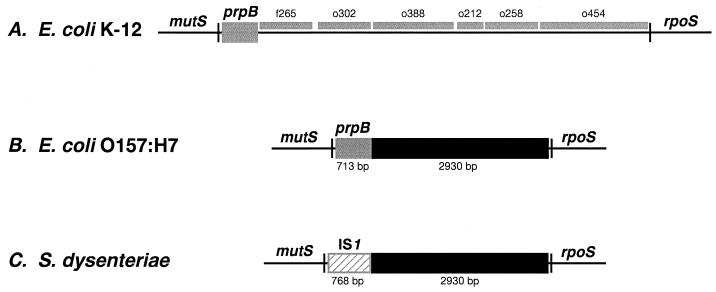

In earlier work (14), long PCR analysis of the intergenic region between the mutS and rpoS genes of E. coli O157:H7 isolate EC536 indicated an apparent deletion of 3.4 kb relative to the expected 6.9-kb intergenic region found in the K-12 strain W3110. To identify the nature of the shortened intergenic region in O157:H7, nucleotide sequencing was performed on PCR products made from primers that spanned the region from the 3′ end of the mutS gene (5′-TGCATCTCGATGCACTGGAG) to the middle of the rpoS gene (5′-CTCAACATACGCAACCTGG) in EC536. The results showed a mutS-rpoS intergenic region of 3,737 bp, of which 2,930 bp had no apparent similarity to the K-12 sequence and replaced 6,098 bp of the K-12 intergenic region. The apparent replacement extended from position 32719 to position 38818 in the 61- to 62-min region of the K-12 chromosome (GenBank accession no. U29579). The results are diagrammed in Fig. 1A and B and show that the deletion from K-12 removes six of the seven open reading frames (ORFs) between the mutS and rpoS genes of the K-12 sequence. The mutS-proximal ORF, which remains intact in O157:H7, shows 95.0% similarity in encoded amino acid sequence and 96.4% identity at the nucleotide level with the recently identified PrpB phosphatase gene sequence (17) (GenBank accession no. U51682, identified as pphB in GenBank accession no. AE000357). Of particular interest, the position of a prpB termination codon in the K-12 sequence is conserved, but the TAG sequence is altered to TAA at the beginning of the novel O157:H7 sequence. The rpoS-proximal end of the deletion encompasses a hairpin structure characteristic of a termination site for transcription of the rpoS gene (9), whose polarity is opposite that of the mutS and prpB genes.

FIG. 1.

(A) Genomic map of the mutS-rpoS region of the E. coli K-12 chromosome based on a published sequence (4) (GenBank accession no. U29579). Seven ORFs between the mutS and rpoS genes are indicated by gray boxes, the first of which has been identified as encoding PrpB phosphatase (17). (B) In E. coli O157:H7, a novel sequence of 2,930 bp replaces six of the seven ORFs found in the E. coli K-12 chromosome and abuts the prpB gene. (C) In S. dysenteriae type 1, a 768-bp IS1 element replaces 713 bp of the prpB gene and abuts the 2,930-bp novel sequence.

In order to determine if the shortened intergenic region is a common feature of the E. coli O157:H7 serotype and to establish how widely this sequence is distributed among pathogenic strains, we used three types of analyses to characterize several independent isolates of O157:H7 outbreak strains, other E. coli strains, and a collection of diverse enteric bacteria. First, colony hybridization experiments (6) were carried out with oligonucleotide probes specific for a site either within the 2,930-bp sequence of O157:H7 (5′-GACATATTCGGCAACTGCAC) or at the rpoS-proximal border of the region (5′-GGCCTTTTTCTTTTGTTTGGG), which contains both the novel O157:H7 sequence and a sequence like that in K-12. Probe-positive strains were then assessed by sizing PCR amplification products from the mutS-rpoS intergenic region. Finally, these PCR products were used for limited DNA sequencing around the border regions of the novel sequence. The results of the colony hybridization experiments, summarized in Table 1, confirmed that all O157:H7 isolates tested, including an O157:H− strain, contained the novel sequence; these encompassed an array of early (1983) to recent (1995) isolates of E. coli O157:H7 outbreak strains. We also identified the novel sequence in strains from two reference collections assembled to represent the genetic diversity of E. coli in nature: diarrheagenic DEC5 strains of the E. coli O55:H7 serotype (the closest known siblings to O157:H7) (25) and strains ECOR37 and ECOR42 from the E. coli reference collection (20), two ECOR strains that were found to be clustered with O157:H7 by the criteria of genetic distance measured by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis and similarity of malate dehydrogenase sequences (21). PCR products from the mutS-rpoS intergenic regions of the ECOR37, ECOR42, and DEC5 strains were the same size as those from O157:H7 isolates, and the nucleotide sequences at border regions around the novel sequence were identical to those in the EC536 isolate. Negative colony hybridization results were obtained when other E. coli strains of the enterohemorrhagic disease class, and other classes, were tested. A diverse group of enteric pathogens also yielded negative colony hybridization results, with the notable exception of strains of Shigella dysenteriae type 1, which were probe positive for oligonucleotides specific to both internal and rpoS-proximal border regions of the novel sequence. Probe and PCR analyses of non-type 1 S. dysenteriae strains and isolates of Shigella boydii, Shigella flexneri, and Shigella sonnei showed much larger mutS-rpoS intergenic regions than that found in E. coli O157:H7, ranging from 8 to 12 kb, and the absence of the novel sequence element (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Colony hybridization with probes based on the novel sequence in E. coli O157:H7

| Species or strain | Internal | rpoS-proximal border | mutS-proximal border |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli O157:H7 | |||

| EC536 | + | + | + |

| EC557 | + | + | + |

| EC558 | + | + | + |

| EC561 | + | + | + |

| EC370 | + | + | + |

| EC507 | + | + | + |

| EC508 | + | + | + |

| EC509 | + | + | + |

| EC504 | + | + | + |

| EC505 | + | + | + |

| EC506 | + | + | + |

| EC440 | + | + | + |

| EC441 | + | + | + |

| E. coli O157:H− | + | + | + |

| E. coli O55:H7 | |||

| DEC5B | + | + | + |

| DEC5D | + | + | + |

| ECOR37 | + | + | + |

| ECOR42 | + | + | + |

| E. coli | |||

| K-12 (W3110) | − | − | − |

| K-12 (C600) | − | − | − |

| O124:NM | − | − | − |

| O25:K98 | − | − | − |

| O78:H11 | − | − | − |

| O78:K80:H12 | − | − | − |

| O111 | − | − | − |

| O26:H11 | − | − | − |

| O165:H25 | − | − | − |

| O26:H11 | − | − | − |

| O26:H30 | − | − | − |

| O127 | − | − | − |

| O55:NM | − | − | − |

| O143 | − | − | − |

| O11:NM | − | − | − |

| O139:ND | − | − | − |

| S. dysenteriae type 1 | |||

| SD567 | + | + | − |

| SD377 | + | + | − |

| 20130 | + | + | − |

| Escherichia hermanii | − | − | − |

| Enterobacter cloacae | − | − | − |

| Proteus vulgaris | − | − | − |

| V. cholerae | − | − | − |

| S. typhimurium | − | − | − |

| Salmonella enteritidis | − | − | − |

| Serratia marcescens | − | − | − |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | − | − | − |

| Listeria monocytogenes | − | − | − |

| Citrobacter freundii | − | − | − |

| Aeromonas hydrophila | − | − | − |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | − | − | − |

S. dysenteriae mutS-rpoS intergenic region.

When filters for colony hybridization were probed with an oligonucleotide (5′-CGGCCTCATTACTTTATTTTAT) encompassing the sequence around the mutS-proximal border of the novel sequence found in EC536, O157:H7 isolates were probe positive while S. dysenteriae type 1 isolates were probe negative (Table 1). We therefore sequenced the mutS-rpoS intergenic region with PCR product prepared from a strain of S. dysenteriae type 1, SD567. PCR product amplified from this region of SD567 was detectably larger on agarose gels than product from EC536. A summary of the nucleotide sequence information is diagrammed in Fig. 1B and C, which illustrate the genomic structures of the region in the two strains. The results showed the novel sequence of 2,930 bp in S. dysenteriae to be 99.5% similar to that in O157:H7 and also showed an identical flanking sequence in the direction of the rpoS gene. On the mutS-proximal side of the novel sequence, 768 bp of unique S. dysenteriae sequence was found in place of 713 bp in K-12 and O157:H7; this sequence element showed 99.3% identity with the mobile insertion sequence IS1 from S. dysenteriae (GenBank accession no. J01731), of which S. dysenteriae contains multiple copies (18). The IS1 element replaces the entire prpB gene sequence, in effect making S. dysenteriae a null mutant of prpB.

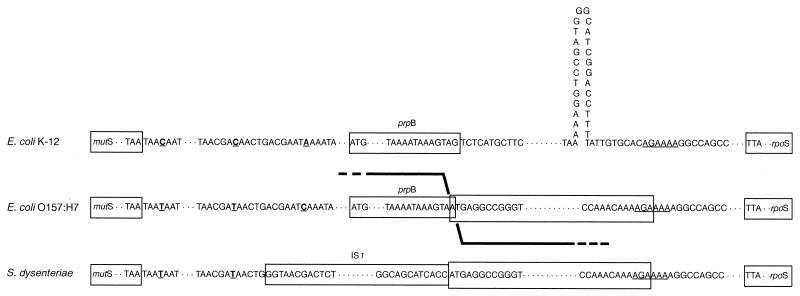

Figure 2 shows sequence comparisons at the borders of elements in the region between the mutS and rpoS genes in E. coli K-12, E. coli O157:H7, and S. dysenteriae. A hypothetical crossover between the K-12 and S. dysenteriae sequences, which could give rise to the novel sequence abutting the prpB gene of O157:H7, is illustrated. Sequences that are identical to that in K-12 at the endpoint of the novel sequence (Fig. 2, underlined) and distinctive nucleotide substitutions downstream from the mutS gene, present in both O157:H7 and S. dysenteriae, suggest that multiple crossovers have occurred in the region. We have examined the surrounding sequence for companion IS1 elements indicative of a specific translocation event; no other elements were revealed by short and long PCR analyses of over 20 kb to either side of the mutS-rpoS intergenic region in strains SD567 and EC536.

FIG. 2.

Nucleotide sequences at border regions of elements in the intergenic region between the mutS and rpoS genes in E. coli K-12 (position no. 32708 to 32731, GenBank accession no. U29579), E. coli O157:H7 (EC536), and S. dysenteriae type 1 (SD567). Elements are boxed, and sequences are shown for the 3′ end of the prpB genes in E. coli K-12 and O157:H7, the 5′ and 3′ ends of the IS1 element in S. dysenteriae, and the border regions of the novel sequence in E. coli O157:H7 and S. dysenteriae. Single-base-pair changes from the K-12 sequence in the mutS-proximal region are underlined. In rpoS-proximal sequences, the dyad symmetry of the rpoS transcription terminator in K-12 is represented and the sequence at the endpoint of the novel sequence (AGAAAA) that is identical to that in K-12 is underlined.

Conclusions.

The finding that the lineage of a unique segment of the E. coli O157:H7 chromosome can be traced to S. dysenteriae implicates a role for horizontal DNA transfer in the evolution of the O157:H7 chromosome. This conclusion is underscored by the presence of a mobile insertion element (IS1) in S. dysenteriae that abuts the same sequence as that identified in O157:H7. The occurrence of the transposable element offers, in part, a mechanism for genetic exchange in an ancestral cell of the O157:H7 lineage. We infer that the DNA exchange occurred between an E. coli O157:H7 ancestor and S. dysenteriae, or a S. dysenteriae-like organism, because the O157:H7 mutS-rpoS intergenic region comprises a sequence identical to that found associated with IS1 in S. dysenteriae (2,930 bp) adjoined to an E. coli K-12-like prpB sequence (713 bp) not present in S. dysenteriae (Fig. 1). The O157:H7 sequence would seem to be the product of a precise crossover, making independent acquisition of the novel sequence in S. dysenteriae and O157:H7 unlikely. Since Shigella species are thought to have evolved from E. coli relatively recently (19), we surmise that the yet more recent O157:H7 strain acquired the mutS-rpoS chromosomal segment from an ancestral lineage that involved horizontal transfer from S. dysenteriae.

It is striking that other gene similarities indicate a flow of genetic information from S. dysenteriae to O157:H7. The O157:H7 genes for shiga-like toxins (stx) show close genetic identity with the shiga toxin of S. dysenteriae (5, 8, 10, 11); they are prophage encoded, indicating the likely mode of DNA transfer from one organism to the other by bacteriophage. Another link is suggested by DNA homology between genes in the two organisms for heme iron transport, genes that are absent from other Shigella species and laboratory strains of E. coli but that show 99.5% sequence identity, namely shuA (S. dysenteriae) and chuA (E. coli O157:H7) (24). As these examples accumulate, the extent to which the evolution of the O157:H7 chromosome involved blending with the S. dysenteriae genome becomes an intriguing question. But we also note evidence that a perosamine synthetase specifying part of the side chain for O antigen from O157 strains is derived from a Vibrio cholerae-like organism (2). The results of genomic sequencing of O157:H7 portray an E. coli genome interspersed with sequences not found in K-12, creating a genome 20% larger than that of K-12 (3). These lines of evidence may be indicative of a more general promiscuous behavior during the evolution of the O157:H7 chromosome that accounts for its chimeric structure.

The mutS-rpoS intergenic sequences characterized here occupy 3.7 kb in E. coli O157:H7 and S. dysenteriae type 1 strains, in contrast to regions with 6.9 kb in E. coli K-12 (4) and 8 to 12 kb in natural isolates of E. coli and Shigella species. In Salmonella typhimurium, an extensive region with 12.6 kb comprises multiple sequence elements (13), yet the neighboring mutS and rpoS genes show respective sequence identities of 83 and 91% in S. typhimurium and E. coli K-12, typical of homologous genes in the two genera. Such local sequence variation earmarks the mutS-rpoS intergenic region as another “bastion of polymorphism” (16), which is indicative of horizontal transfer events. This serves notice that, akin to mutational hot spots, there exist regions of the chromosome that may be hot or cold for recombination.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

GenBank accession no. AF054420 and AF055472 have been assigned to the sequences for the mutS-rpoS intergenic regions of E. coli O157:H7 and S. dysenteriae type 1, respectively.

Acknowledgments

We thank F. R. Blattner for discussing results prior to publication, Philip Tarr and Tom Whittam for generously providing clinical isolates of E. coli O157:H7 and O55:H7 strains, and Howard Ochman for the ECOR collection.

REFERENCES

- 1.Besser R E, Lett S M, Weber J T, Doyle M P, Barrett T J, Wells J G, Griffin P M. An outbreak of diarrhea and hemolytic uremic syndrome from Escherichia coli O157:H7 in fresh-pressed apple cider. JAMA. 1993;269:2217–2220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bilge S S, Vary J C, Jr, Dowell S F, Tarr P I. Role of the Escherichia coli O157:H7 O side chain in adherence and analysis of an rfb locus. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4795–4801. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4795-4801.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blattner, F. R. Personal communication.

- 4.Blattner F R, Plunkett III G, Bloch C A, Perna N T, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Vides J, Glasner J D, Rode C K, Mayhew G, Gregor J, Davis N W, Kirkpatrick H A, Goeden M A, Rose D, Mau B, Shao Y. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 1997;277:1453–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calderwood S B, Auclair F, Donohue-Rolfe A, Keusch G T, Mekalanos J J. Nucleotide sequence of the shiga-like toxin genes of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:4364–4368. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.13.4364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cebula T A, Koch W H. Analysis of spontaneous and psoralen-induced Salmonella typhimurium hisG46 revertants by oligodeoxyribonucleotide colony hybridization: use of psoralens to cross-link probes to target sequences. Mutat Res. 1990;229:79–87. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(90)90010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Escherichia coli O157:H7 outbreak linked to commercially distributed dry-cured salami—Washington and California. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 1995;44:157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Grandis S, Ginsberg J, Toone M, Climie S, Frisen J, Brunton J. Nucleotide sequence and promoter mapping of the Escherichia coli shiga-like toxin operon of bacteriophage H19B. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:4313–4319. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.9.4313-4319.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iriarte M, Stainier I, Cornelis G R. The rpoS gene from Yersinia enterocolitica and its influence on expression of virulence factors. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1840–1847. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1840-1847.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson M P, Neill R J, O'Brien A D, Holmes R K, Newland J W. Nucleotide sequence analysis and comparison of the structural genes for shiga-like toxin I and shiga-like toxin II encoded by bacteriophages from Escherichia coli 933. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1987;44:109–114. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(87)90106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jackson M P, Newland J W, Holmes R K, O'Brien A D. Nucleotide sequence analysis of the structural genes for shiga-like toxin I encoded by bacteriophage 933J from Escherichia coli. Microb Pathog. 1987;2:147–153. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(87)90106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keene W E, Sazie E, Kok J, Rice D H, Hancock D D, Balan V K, Zhao T, Doyle M P. An outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections traced to jerky made from deer meat. JAMA. 1997;277:1229–1231. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03540390059036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kotewicz, M. L., B. Li, D. D. Levy, J. E. LeClerc, and T. A. Cebula. Unpublished data.

- 14.LeClerc J E, Li B, Payne W L, Cebula T A. High mutation frequencies among Escherichia coli and Salmonella pathogens. Science. 1996;274:1208–1211. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5290.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin M L, Shipman L D, Wells J G, Potter M E, Hedberg K, Wachsmuth I K, Tauxe R V, Davis J P, Arnoldi J, Tilleli J. Isolation of Escherichia coli O157:H7 from dairy-cattle associated with two cases of hemolytic uremic syndrome. Lancet. 1986;ii:1043. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)92656-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Milkman R. Recombination and population structure in Escherichia coli. Genetics. 1997;146:745–750. doi: 10.1093/genetics/146.3.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Missiakas D, Raina S. Signal transduction pathways in response to protein misfolding in the extracytoplasmic compartments of E. coli: role of two new phosphoprotein phosphatases PrpA and PrpB. EMBO J. 1997;16:1670–1685. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.7.1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nyman K, Nakamura K, Ohtsubo H, Ohtsubo E. Distribution of the insertion sequence IS1 in gram-negative bacteria. Nature (London) 1981;289:609–612. doi: 10.1038/289609a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ochman H, Groisman E A. The evolution of invasion by enteric bacteria. Can J Microbiol. 1995;41:555–561. doi: 10.1139/m95-074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ochman H, Selander R K. Standard reference strains of Escherichia coli from natural populations. J Bacteriol. 1984;157:690–693. doi: 10.1128/jb.157.2.690-693.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pupo G M, Karaolis D K R, Lan R, Reeves P R. Evolutionary relationships among pathogenic and nonpathogenic Escherichia coli strains inferred from multilocus enzyme electrophoresis and mdh sequence studies. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2685–2692. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2685-2692.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riley L W, Remis R S, Helgerson S D, McGee H B, Wells J G, Davis B R, Hebert R J, Olcott E S, Johnson L M, Hargrett P A, Blake P A, Cohen M L. Hemorrhagic colitis associated with a rare Escherichia coli serotype. N Engl J Med. 1982;308:681–685. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198303243081203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takeda Y. Enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli. World Health Stat Q. 1997;50:74–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Torres A G, Payne S M. Haem iron-transport system in enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:825–833. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2641628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whittam T S, Wolfe M L, Wachsmuth I K, Ørskov F, Ørskov I, Wilson R A. Clonal relationships among Escherichia coli strains that cause hemorrhagic colitis and infantile diarrhea. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1619–1629. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.1619-1629.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]