Abstract

Objective

Few studies employ culturally safe approaches to understanding Indigenous women’s experiences of intimate partner violence (IPV). The aim of this study was to develop a brief, culturally safe, self-report measure of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women’s experiences of different types of IPV.

Design

Multistage process to select, adapt and test a modified version of the Australian Composite Abuse Scale using community discussion groups and pretesting. Revised draft measure tested in Wave 2 follow-up of an existing cohort of Aboriginal families. Psychometric testing and revision included assessment of the factor structure, construct validity, scale reliability and acceptability to create the Aboriginal Women’s Experiences of Partner Violence Scale (AEPVS).

Setting

South Australia, Australia.

Participants

14 Aboriginal women participated in discussion groups, 58 women participated in pretesting of the draft version of the AEPVS and 216 women participating in the Aboriginal Families Study completed the revised draft version of the adapted measure.

Results

The initial version of the AEPVS based on item review and adaptation by the study’s Aboriginal Advisory Group comprised 31 items measuring physical, emotional and financial IPV. After feedback from community discussion groups and two rounds of testing, the 18-item AEPVS consists of three subscales representing physical, emotional and financial IPV. All subscales had excellent construct validity and internal consistency. The AEPVS had high acceptability among Aboriginal women participating in the Aboriginal Families Study.

Conclusions

The AEPVS is the first co-designed, multidimensional measure of Aboriginal women’s experience of physical, emotional and financial IPV. The measure demonstrated cultural acceptability and construct validity within the setting of an Aboriginal-led, community-based research project. Validation in other settings (eg, primary care) and populations (eg, other Indigenous populations) will need to incorporate processes for community governance and tailoring of research processes to local community contexts.

Keywords: PUBLIC HEALTH, EPIDEMIOLOGY, MENTAL HEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The Aboriginal Women’s Experiences of Partner Violence Scale is the first co-designed, multidimensional measure of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women’s experience of physical, emotional and financial partner violence.

The measure demonstrated cultural acceptability and construct validity within the setting of an Aboriginal-led, community-based research project.

The research team worked with guidance of the study’s Aboriginal Advisory Group and Aboriginal women participating in discussion groups to ensure content validity and cultural acceptability of the new measure.

While the sample was both geographically and culturally diverse, the results may not apply directly to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities in other jurisdictions or to other Indigenous populations.

Background

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a global public health and human rights issue estimated to affect one in three women at some stage in their lives.1 An Australian longitudinal study of over 1500 first-time mothers found that more than one in three women experienced IPV in the decade after having their first child.2 Indigenous women are disproportionately impacted by family and community violence due to ongoing impacts of colonisation, including: racism and discrimination; disconnection from traditional lands, culture and language; policies of forced child removal; and constant grief and loss.3–6 There is mounting evidence of the long-term health consequences of IPV for women and children.2 6–10 Advocacy programmes, focusing on empowerment, safety and resources, and psychological therapies, such as trauma-informed cognitive–behavioural therapy have been shown to be effective in long-term healing and recovery from IPV.11 12 However, most women and children impacted by IPV do not access such services.6 13–16 Barriers operate at both organisational and systems levels (eg, fragmented referral pathways, low affordability, insufficient attention to tailoring of care to address needs of culturally diverse communities) and at a personal or family level (eg, minimising significance of the problem, belief that nothing will help, shame, self-doubt and low self-esteem, concerns about escalation of violence and risk of child removal).6 17 At a global level, the WHO has called for systems change to strengthen health sector responses to IPV.18 19 In Australia, two recent Royal Commissions have drawn attention to the need for systems reform to improve prevention and early intervention, and for service responses to be developed in partnership with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.20 21

There is high quality evidence regarding the prevalence of IPV and longer-term consequences for women’s and children’s health from large scale studies conducted in high, middle and low income countries.1 2 8 9 Globally, the experience of Indigenous women remains underinvestigated. To our knowledge there are no culturally validated tools for inquiring about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women’s experiences of IPV. To address this gap, we adapted an Australian multidimensional measure of physical and emotional IPV—the Composite Abuse Scale22 23—for inclusion in a longitudinal study of 344 Aboriginal families in South Australia.

Partner violence takes many forms. The most commonly recognised types of IPV are acts of physical and sexual violence. IPV also takes the form of repeated emotional abuse and/or coercive, controlling behaviour, which may include control of financial resources. There is some evidence that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women experience high rates of physical violence.13 It is not known how commonly Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women experience other forms of partner violence, nor what consequences this has for their health and well-being, or the health and well-being of children.

This study—conducted in partnership with the Aboriginal Health Council of South Australia—aimed to develop a culturally robust and acceptable approach to inquiring about IPV within an existing prospective birth cohort study called the Aboriginal Families Study. This paper reports iterative steps taken to: (1) select and adapt an existing multidimensional measure of intimate partner violence; and (2) test the cultural acceptability and psychometric properties of the adapted measure within Wave 2 follow-up of the cohort.

Methods

Setting

The Aboriginal Families Study is a prospective, population-based cohort study of 344 Aboriginal children born in South Australia between July 2011 and June 2013, and their mothers and carers. The study protocol was developed with guidance from the study’s Aboriginal Advisory Group set up under the auspice of the Aboriginal Health Council of South Australia (the peak body for Aboriginal health in South Australia). Women were recruited by a team of Aboriginal researchers, all of whom had close connections with Aboriginal communities in South Australia. Details regarding community consultation, partnership arrangements and study procedures are available in previous papers.24 25

Cohort participants have connections with more than 35 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander language and community groups across Australia. At recruitment, 39% of women were living in Adelaide, 36% in regional areas and 25% in remote areas of South Australia. Women ranged in age from 15 to 49 years. Comparisons with South Australian routinely collected perinatal data showed that the sample was largely representative in relation to maternal age, infant birth weight and gestation, but slightly over-represented women having their first child.25 Wave 2 follow-up of children and their mothers and carers was undertaken between 2018 and 2020 around the time that the children were starting primary school.

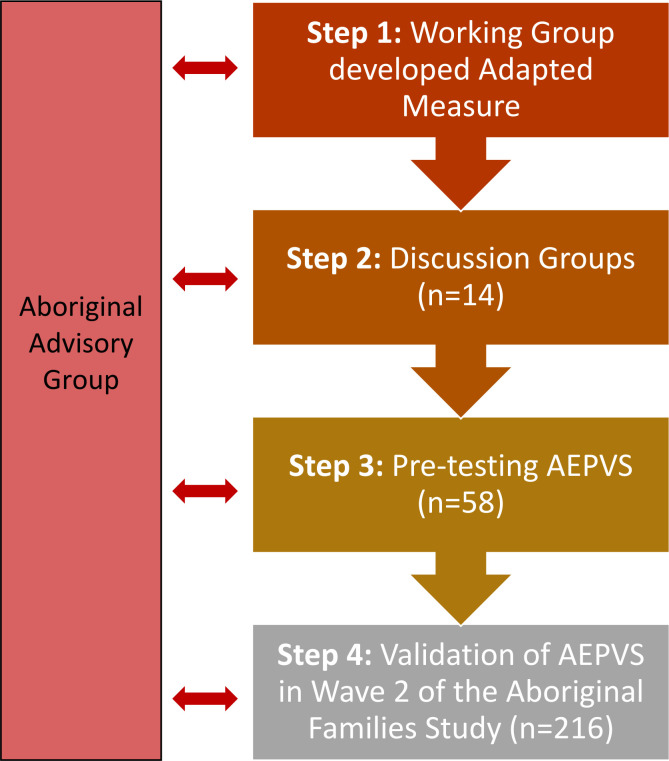

Prior to commencing Wave 2 follow-up, the research team and the study’s Aboriginal Advisory Group undertook extensive preparatory work to design procedures for follow-up. This included selection of culturally appropriate study measures. The steps involved are outlined in figure 1. At Wave 2, the study aims included ascertainment of women’s experiences of violence in partner relationships. To address this aim, the research team reviewed existing measures of IPV and looked for epidemiological and clinical studies involving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders or other Indigenous populations where measures of IPV had been used. Instruments included in the CDC Compendium of Assessment Tools for Measuring Intimate Partner Violence Victimization and Perpetration26 were reviewed in relation to: (1) likely face validity with Aboriginal women of childbearing age in South Australia; (2) culturally appropriate use of language; (3) length of the measure; (4) capacity to be completed as an interview or by self-administered questionnaire; (5) inclusion of items asking about different types of violence, including physical, emotional and financial abuse; (6) robust psychometric properties. Based on these criteria, the Composite Abuse Scale (CAS) was selected by the Aboriginal Advisory Group as the measure most likely to be suitable for inclusion. The standard version includes 30 items assessing different types of psychological, physical and sexual violence by a current or former partner over the previous 12 months.22 23 A shorter, 18-item version focuses on emotional and physical violence. Both versions have been used extensively in Australian and international research.2 27–31 The Aboriginal Advisory Group recommended that the 18-item version be adapted and pretested with Aboriginal women to determine whether it would be appropriate for inclusion in the Wave 2 questionnaire. Specifically, the Advisory Group recommended: (1) review of the language in the CAS for cultural and linguistic relevance, (2) inclusion of additional items to assess financial abuse and (3) inclusion of additional items covering actions by a partner that seek to control women’s behaviour, including actions that seek to prevent women from connecting with members of their Aboriginal family or going to Aboriginal community events.

Figure 1.

Steps involved in developing and validating the Aboriginal Experiences of Partner Violence Scale (AEPVS).

Step 1: development of the adapted CAS

A working group—comprising Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal investigators, Aboriginal researchers and members of the Aboriginal Advisory Group—was established to make recommendations regarding adaptation of the CAS (table 1). Working Group members were asked to review the original 18-item version of the CAS for acceptability and suitability for use with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women of childbearing age living in South Australia. Modifications recommended by the working group included changes to the wording of some items to simplify language and/or change the expression to match local Aboriginal ways of using English. For example, the expression ‘Beat you up’ (a common expression in standard Australian English) was replaced with the expression ‘Flogged you’ (a more common expression in Aboriginal English). While few women taking part in the Aboriginal Families Study speak an Aboriginal language at home, many speak some words in local Aboriginal languages. The working group recommended inclusion of some words in local languages likely to be familiar to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in South Australia.

Table 1.

Items in the Composite Abuse Scale and draft Aboriginal Women’s Experiences of Partner Violence Scale (AEPVS)—versions 1 and 2

| Composite Abuse Scale—short version | Initial draft version of the AEPVS | Final draft version of the AEPVS |

| Emotional abuse items | ||

| Told me I was not good enough | Told you that you are no good | Told you that you are stupid or no good |

| Tried to turn my family, friends and children against me | Tried to turn family, friends and children against you | Tried to turn family, friends and children against you |

| Tried to keep me from seeing or talking to my family | Tried to keep you from seeing or talking to family | Tried to keep you from seeing or talking to family |

| Blamed me for causing their violent behaviour | Blamed their violent behaviour on you, saying it was your fault because you set them off | Blamed their violent behaviour on you, saying it was your fault because you set them off |

| Told me I was crazy | Told you that you are crazy (boontha, rama rama) | Told you that you are crazy (boontha, rama rama) |

| Told me no one would ever want me | Told you that no one would ever want you | Told you that no one would ever want you |

| Did not want me to socialise with my female friends | Stopped you from seeing female friends | Stopped you from seeing female friends |

| Told me I was stupid | Told you that you are stupid | |

| Told me I was ugly | Told you that you are ugly | |

| Became upset if dinner/house work was not done when they thought it should be | ||

| Tried to convince my friends, family or children that I was crazy | Tried to convince friends, family or children that you have lost your spirit, or have bad spirit in you | |

| Got jealous or wild (doodla) if you talked to your male friends or their male friends | Got jealous or wild (doodla) if you talked to your male friends or their male friends | |

| Got wild when you dressed up or put makeup on | Got wild when you dressed up or put makeup on | |

| Threatened to hurt you, your family or pets | Threatened to hurt you, your family or pets | |

| Stopped you from connecting with your Aboriginality (eg, going to community events, going home to Country) | Stopped you from connecting with your Aboriginality (eg, going to community events, going home to Country) | |

| Made you feel bad about being Aboriginal | Made you feel bad about being Aboriginal | |

| Physical abuse items | ||

| Slapped me | Slapped or hit you | Slapped or hit you |

| Shook me | Shook you | Shook you |

| Pushed, grabbed or shoved me | Pushed, grabbed or shoved you | Pushed, grabbed or shoved you |

| Hit or tried to hit me with something | Hit or tried to hit you with something | Hit or tried to hit you with something |

| Kicked me, bit me or hit me with a fist | Kicked you, bit you or punched you | Kicked you, bit you or punched you |

| Beat me up | Flogged you | Flogged you |

| Threw me | ||

| Stopped you from leaving the house | Stopped you from leaving the house | |

| Forced you to do something you did not want to do | Forced you to do something you did not want to do sexually | |

| Smashed up or destroyed your things | Smashed up or destroyed your things | |

| Used a knife or gun or other weapon | ||

| Financial abuse items | ||

| Got wild if you spent money on yourself | Got wild if you spent money on yourself | |

| Refused to contribute to family finances (eg, pay bills, buy food) | Refused to contribute to family finances (eg, pay bills, buy food) | |

| Stopped you from earning your own money | Stopped you from earning your own money | |

| Got you to pay their bills | Got you to pay their bills | |

| Took money from your bank account | Took money you needed for something else (eg, pay bills, buy food) | |

| Took your money | Took your money and made you worry about not having enough | |

| Made you put the bills in your name | Made you put the bills in your name | |

| Made you ask for money for bills, food or the kids | Made you ask for money for bills, food or the kids |

Sixteen new items considered to have particular relevance for Aboriginal communities were added to the measure. These were: two items asking about controlling behaviour preventing women from connecting with their Aboriginality or making women feel bad about being Aboriginal; seven items asking about financial abuse; four items describing types of physical abuse; and three items describing emotional abuse.

In the original version of the CAS, women are asked to report the frequency of each behaviour during the previous 12 months, by ticking one of the following six responses: ‘never’, ‘only once’, ‘several times’, ‘once per month’, ‘once per week’ and ‘daily’, scored 0–5. A score of 3 or more for emotional abuse items or 1 or more for physical abuse items is used to indicate IPV.22 23 The working group recommended that the number of response options be reduced from six to four for ease of administration. The pilot study version included the following four responses: ‘never’, ‘once’, ‘several times’ or ‘a lot’, scored 0–3. The working group also recommended inclusion of a preamble explaining why the questions were being asked, that all women were being asked the same questions and reminding women that they did not have to answer any questions that they did not wish to answer. Questions in the draft measure were worded in the second person (you/your) to facilitate administration as an interview. This was also seen as potentially more comfortable for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women to self-complete. The new draft measure was named the Aboriginal Women’s Experiences of Partner Violence Scale (AEPVS).

Step 2: discussion groups

Discussion groups were held in urban and regional areas to seek advice on the acceptability of the proposed approach, and cultural appropriateness of the draft AEPVS. Eligible women (aged ≥18 years; mothers of Aboriginal children aged 6–10 years) were recruited via Aboriginal community organisations, health services and community centres. Staff in these agencies informed women about the study and facilitated introductions to members of the research team, who then explained what was involved in taking part. Women were provided with written and verbal information, and given time to consider their decision before agreeing to take part. Discussion group methods were used to examine the content of the draft AEPVS, paying particular attention to specific items and response options, and use of Aboriginal language words. After a preliminary discussion about the purpose of the study, and principles for participation, participants were given copies of the standard version of the CAS and the draft AEPVS and asked to comment on which instrument offered the better approach for Aboriginal women. Participants were then asked to look at individual items in the CAS and the draft AEPVS and to comment on their suitability for inclusion. The principles for participation in discussion groups included agreements regarding confidentiality, the importance of everyone being heard and there being no right and wrong answers. All discussion groups were facilitated by Aboriginal research team members, with notes taken on butchers’ paper.

Step 3: pretesting the new Aboriginal Women’s Experiences of Partner Violence measure

The Wave 2 questionnaire incorporating the draft AEPVS was pretested with Aboriginal women living in urban and regional areas between October 2016 and August 2017. Women were eligible to take part if they were aged ≥18 years and mothers of Aboriginal children aged 6–10 years old. Eligible women were identified via community networks of Aboriginal research team members with connections to different communities in South Australia and were offered the choice of completing the questionnaire with an Aboriginal researcher or self-completing the questionnaire. Women consenting to participate were asked for their written and/or verbal feedback on the draft questionnaire including the questions on partner violence. Specifically, they were asked: (1) whether there were any questions or sections of the questionnaire that made them feel uncomfortable or that were ‘too personal’ or ‘intrusive’; (2) what they liked about the questionnaire; and (3) what we could do to improve the questionnaire, specific questions or study procedures.

Step 4: validation of the AEPVS in Wave 2 of the Aboriginal Families Study

Wave 2 follow-up occurred between mid-2018 and late 2020. All women who took part in Wave 1 were eligible to take part. Women were invited to complete the questionnaire in a face-to-face interview with a female Aboriginal researcher, or to self-complete (if preferred). When women opted to self-complete, study staff either remained present or provided participants with a folder for storing the completed questionnaire, which was then collected within 48 hours by the same team member. Care was taken to inform women that the questionnaire covered sensitive issues such as grief and loss and partner violence, and that they did not have to answer any questions that they do not wish to. Study staff aimed to ensure that interviews took place in locations where women had privacy, and that questionnaires left for self-completion were contained in a sealable envelope or folder to facilitate confidentiality. During the COVID-19 pandemic, women were also given the option of receiving a mailed copy of the questionnaire and/or mailing the questionnaire back to the research team by reply paid envelope. Safety procedures included training and support for study staff to offer referral pathways to women disclosing violence or other life stressors.

Analysis

Data gathered in discussion groups (step 2) were analysed to identify areas of consensus, disagreement or concern about the draft AEPVS items and/or study procedures related to inquiry about partner violence. Analysis of data collected from women participating in pretesting of the draft questionnaire (step 3) involved examining item distributions and missing values for each of the AEPVS items. Women’s feedback about the AEPVS items was also collated and summarised. These combined data were presented to members of the Aboriginal Advisory Group and study investigators for their consideration and interpretation and were used to inform final decisions regarding study measures and procedures for Wave 2 follow-up.

Validation of the AEPVS (step 4) was conducted using data collected from women who participated in Wave 2 follow-up. Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were conducted for the three subscales—emotional, physical and financial IPV—using MPlus. The AEPVS items were ordinal level data with four response options and generally non-normal in their distribution, therefore robust weighted least squares estimation (WLSMV) was used. The adequacy of the models was assessed using goodness-of-fit χ2, and practical fit indices including the Comparative Fit Index, Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI) and Adjusted GFI (AGFI) with estimates of 0.90 or above indicating acceptable model fit.32 The root mean square error of approximation was also used with values close to or below 0.05 within the 90% CI indicating good model fit.33 Standardised factor loadings, error variances, standardised residuals and modification indices were examined to identify potential items contributing to poor model fit. An iterative process was used in which the model was re-estimated and examined after each modification until the model fit was adequate. Internal consistency reliability for each subscale was examined using Cronbach α, with 0.7–0.9 deemed good to excellent.34 35 Scoring for the AEPV emotional and physical partner violence scales replicated the original CAS (≥3 and ≥1, respectively). Scoring for the financial partner violence scale was set at ≥2.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved in the study. The study was conducted in partnership with the Aboriginal Health Council of South Australia and was preceded by extensive community consultations with Aboriginal communities in rural, regional and remote South Australia. Community consultations identified family violence as an issue of concern. The Aboriginal Advisory Group established to oversee the study guided the research team in the best approaches to undertaking the research in ways that were respectful of Aboriginal families and prioritised the cultural safety of participants and study staff. Participatory methods were used throughout. For example, a working group comprising Aboriginal Advisory Group members, Aboriginal researchers and Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal study investigators was established to facilitate cultural adaptation of the CAS. Discussion groups were held in urban and regional areas to seek community feedback on the draft AEPVS and proposed study procedures. The Aboriginal Advisory Group worked with study staff and investigators to guide decision-making at each stage of the research and gave final approval for publication. Authors of this paper include members of the Aboriginal Advisory Group, Aboriginal study investigators and Aboriginal study staff.

Results

Step 2: discussion group feedback

Fourteen women participated in five discussion groups (two to four women in each). Two groups were held in regional areas and three in a major city. In all five discussion groups, participants told us that they preferred the draft AEPVS, and considered this to be much more culturally appropriate than the original CAS. There was strong support for inclusion of:

Items in the AEPVS on emotional, physical and financial abuse.

The two items asking about abuse related to Aboriginality.

The use of Aboriginal words familiar to South Australian Aboriginal women.

While there was strong support for the inclusion of Aboriginal words in some items, there were differing views regarding the best words to use. There were also mixed views about the decision not to include questions asking about sexual abuse. Women attending separate urban discussion groups independently raised this as an issue and argued for inclusion of at least one item asking about sexual abuse. Women attending a rural discussion group, on the other hand, were uncomfortable with the idea of asking women directly about sexual abuse. One other item which asked about a partner/former partner ‘trying to convince friends, family or children that you have lost your spirit, or that you have bad spirit in you’ was seen as having potential to cause distress.

Step 3: results of pre-testing the AEPVS

Fifty-eight women completed one of three draft versions of the Wave 2 follow-up questionnaire (9 as an interview and 49 by filling in the questionnaire themselves). Participants included women living in urban, regional and remote areas of South Australia. Overall, feedback was very positive. Women indicated that they found the questions ‘easy to read and understand’, ‘to the point’, ‘relevant’, ‘straightforward’ and ‘honest’. Women also commented that they liked the questions about ‘our culture’, ‘how it flowed’, ‘all the questions themselves’ and ‘being real when asking the questions, not tip-toeing around’. Several women said they liked that they did not have to answer anything that they did not want to and commented that it was good that they were told beforehand about the ‘sensitive’ questions as it meant they were ‘prepared for these questions’ prior to undertaking the survey. Five women (8.9%) said that they thought some of the questions were a bit too personal, in particular the questions asking about partner violence and drugs and alcohol.

Modifications to the draft AEPVS

Analyses of results for the 42 women who completed the initial draft version of the AEPVS were considered alongside feedback from participants (including those taking part in discussion groups and those completing draft versions of the questionnaire). Individual items retained in the AEPVS are discussed below, together with examples of changes made based on the adaptation process.

Physical IPV

The initial version of the draft AEPVS retained six of the original CAS items asking about physical IPV and included an additional three items covering different contexts/ways in which physical violence may occur (see table 1). New items were worded as follows: ‘Smashed up or destroyed your things’, ‘Stopped you from leaving the house’, ‘Forced you to do something you didn’t want to do’. In addition, two items were re-worded to reflect Aboriginal use of English.

Two items showed poor distribution but were retained for further testing as they formed part of the original scale (Kicked bit or punched you, Flogged you). Overall the physical IPV scale had excellent internal reliability as a scale (Cronbach α=0.96). The final approved version of the AEPVS (table 1) also includes an item asking about whether a partner or ex-partner ‘Used a knife or gun or other weapon’. The Aboriginal Advisory Group approved inclusion of this item to measure more extreme physical violence. In addition, the Aboriginal Advisory Group recommended a change to the last item. This was revised to read: ‘Forced you to do something you didn’t want to do sexually’ to respect the feedback from two urban discussion groups, while also respecting the view expressed in a regional discussion group that sexual violence should not be asked about directly.

Emotional IPV

Ten of the original CAS items asking about emotional IPV were retained in the initial version of the AEPVS (table 1). One item asking whether partners ‘Became upset if dinner/housework wasn’t done when they thought it should be’ was seen as having limited relevance as a form of abuse in Aboriginal families given the varied nature of household structures and high proportion of women living with other family and/or not living with their partner. Four of the retained items were reworded to reflect Aboriginal use of English. For example, ‘Did not want you to socialise with your female friends’ was revised to read ‘Stopped you from seeing your female friends’. Five items were added to cover specific contexts particularly relevant to Aboriginal women. These included contexts in which a non-Aboriginal partner might seek to control women’s behaviour by preventing women from connecting with their Aboriginal family or culture, or making women feel bad about being Aboriginal. In the final consensus version, all of these items were retained (table 1). The item referring to ‘bad spirit’ was removed based on feedback from discussion groups and poor item distribution. One other item—‘Told you that you are ugly’ was also removed based on poor item distribution. In the final version, two items were amalgamated to read ‘Told you that you are stupid or no good”. This change was to reduce the total number of items measuring emotional abuse.

Financial IPV

The original 18-item CAS does not include any items measuring financial abuse. The longer 30-item version includes one item. This item ‘Took my wallet and left me stranded’ was simplified to read ‘Took your money’ as the phrase ‘left me stranded’ did not resonate with members of the Aboriginal Advisory Group. An extra seven items were included in the initial version of the AEPVS based on the existing literature on financial abuse and to reflect a range of ways in which financial abuse may be experienced by Aboriginal women (table 1). Minor changes were made to two of these items to be more specific in terms of negative impact. The item ‘Took your money’ was revised to read ‘Took your money and made you worry about not having enough’, and the item ‘Took money from your bank account’ was revised to read ‘Took money you needed for something else (eg, pay bills, buy food)’.

Response categories and initial framing of the measure

The wording and number of response categories in the AEPVS were reviewed by discussion group participants and were considered readily understood. The original wording of the introductory sentence was seen as too complex and was simplified in the final version to read ‘In the LAST 12 MONTHS, has a partner or ex-partner ever….’, followed by the 30 individual items.

Situating the AEPVS in the Wave 2 questionnaire

The Aboriginal Advisory Group emphasised that women needed to be given clear information regarding the purpose for asking questions about partner violence and an explanation about how the data gathered would be used to benefit Aboriginal families and communities. The research team tested two versions of a preamble to the section that included the draft AEPVS. The final preamble conveyed to women that the:

Aboriginal Advisory Group wants the study to give women an opportunity to talk about their experiences of partner violence, so that the information can be used to advocate for better services and support for women and families.

Preceding this statement, the preamble noted:

Many Aboriginal women and men have healthy relationships. We know there are negative stereotypes about violence in Aboriginal families. Our aim is to ensure that the information given to us is used to benefit the community, and not used to reinforce negative stereotypes.

There was also a specific reminder to women at this point in the questionnaire that they could choose not to answer any of the questions they did not wish to. Women who completed the questionnaire as an interview were also given the option of choosing to self-complete this section.

In addition, the Aboriginal Advisory Group recommended that a question be included immediately following the AEPVS to inquire about what women do to stay strong and protect themselves when these things happen. This question was regarded as important to dispel stereotypes that Aboriginal women do not act to protect themselves and their children.

Step 4: validation study

A total of 227 women participated in Wave 2 follow-up (see table 2). A majority were Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islanders (207, 91.2%). The mean age at the birth of the study child was 25.4 (range 14.9–43.4 years). Women who participated in Wave 2 follow-up were largely representative of the original cohort in relation to maternal age and Indigenous status. At Wave 2 follow-up, less than half were living with a partner (41.2%), one in 10 (9.7%) had a partner but were not living in the same household and 49.1% were single. Just under half of the women participating in Wave 2 were living in the major metropolitan city of Adelaide, approximately one-third in regional areas of South Australia, and just under one in five in areas classified as remote. This reflects the slightly higher participation of women living in urban areas and slightly lower participation of women living in remote areas in Wave 2 compared with Wave 1.

Table 2.

Socio-demographic characteristics of women participating in Waves 1 and 2 of the Aboriginal Families Study and completing the draft Aboriginal Women’s Experiences of Partner Violence Scale (AEPVS) at Wave 2

| Wave 1 (n=344) n (%) |

Wave 2 (n=227) n (%) |

AEPVS (Wave 2) (n=216) n (%) |

|

| Maternal age at birth of study child | |||

| 15–19 years 20–24 years 25–29 years 30–35 years 35+ years |

55 (16.0) 140 (40.7) 91 (26.5) 33 (9.6) 25 (7.3) |

34 (15.0) 89 (39.2) 62 (27.3) 25 (11.0) 17 (7.5) |

32 (14.8) 86 (39.8) 58 (26.9) 23 (10.7) 17 (7.9) |

| Indigenous status | |||

| Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander Non-Aboriginal* |

319 (92.7) 25 (7.3) |

207 (91.2) 20 (8.8) |

196 (90.7) 20 (9.3) |

| Relationship status (Wave 2) | |||

| Single Living with partner In relationship, not living with partner |

Not asked | 111 (49.1) 93 (41.2) 22 (9.7) |

103 (47.9) 90 (41.9) 22 (10.2) |

| Place of residence | |||

| Metropolitan area Regional Remote |

134 (39.0) 123 (35.8) 87 (25.3) |

101 (44.7) 81 (35.8) 44 (19.5) |

97 (45.1) 75 (34.9) 43 (20.0) |

| Number of adults in household | |||

| One Two Three or more |

56 (16.9) 157 (47.3) 119 (35.8) |

81 (35.8) 112 (49.6) 33 (14.6) |

74 (34.4) 108 (50.2) 33 (15.4) |

| Own children living with participant | |||

| None One to two Three to four Five or more |

2 (0.6) 233 (68.9) 81 (24.0) 22 (6.5) |

8 (3.5) 93 (41.0) 99 (43.6) 27 (11.9) |

7 (3.2) 89 (41.2) 95 (44.0) 25 (11.6) |

| Total number of children living with participant | |||

| None One to two Three to four Five or more |

2 (0.6) 193 (58.1) 97 (29.2) 40 (12.1) |

7 (3.1) 87 (38.3) 95 (41.9) 38 (16.7) |

6 (2.8) 83 (38.4) 91 (42.1) 36 (16.7) |

| Highest educational qualification | |||

| University degree Diploma/certificate Year 12 Less than Year 12 |

22 (6.4) 155 (45.1) 33 (9.6) 134 (39.0) |

16 (7.1) 126 (55.1) 19 (8.4) 66 (29.1) |

15 (6.9) 124 (57.4) 19 (8.8) 58 (26.8) |

| Paid employment | |||

| Full-time job Part-time job Not in paid employment |

14 (4.1) 23 (6.8) 303 (89.1) |

33 (14.6) 45 (19.9) 148 (65.5) |

33 (15.4) 45 (20.9) 137 (63.7) |

| Healthcare card | |||

| No Yes |

44 (12.9) 296 (87.1) |

51 (22.5) 176 (77.5) |

49 (22.7) 167 (77.3) |

*Non-Aboriginal women taking part are mothers of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander children.

The AEPVS was completed by 216 women, with very few missing data points observed for individual items (range 0–6). The 11 women who chose not to answer this section ranged in age from 19.4 to 32.7 years (mean=26.1 years, SD=4.8) at the time of giving birth to the study child. The majority were single (72.7%) and lived in regional areas (60%). These women were not included in subsequent analyses.

Table 3 reports the mean and SD for each item included in the draft AEPVS, as well as the standardised factor loadings, proportion of the variance accounted for (R2) and error variances for each item in the initial and final CFAs tested. The three initial models of the emotional, physical and financial IPV subscales were a good fit to the data, with high factor loadings for all items (≥74). As the goal was to achieve a brief multidimensional measure, each subscale was further refined to reduce the number of items. Decisions to remove items were based on item distributions, factor loadings, proportion of variance accounted for in the construct by the items and error variances. Changes were sequential and model fit re-assessed with each change. The final CFA models showed excellent model fit to the data (see table 3).

Table 3.

Final draft items and the initial and final confirmatory factor analysis solutions to create the Aboriginal Women’s Experiences of Partner Violence Scale (n=216)

| Item | Initial model | Final model | ||||||

| n | Mean (SD) | Standardised factor loadings | R2 | Error variance | Standardised factor loadings | R2 | Error variance | |

| Emotional partner violence | χ2(54) = 81.95, p=0.008, RMSEA=0.05 (0.03, 0.07), CFI=1.00, TLI=1.00, SRMR=0.04 | χ2 (9) = 9.02, p=0.436, RMSEA=0.003 (0.00, 0.08), CFI=1.00, TLI=0.99, SRMR=0.02 | ||||||

| Told you that you are stupid or no good | 214 | 0.58 (0.97) | 0.92 | 0.84 | 0.16 | 0.92 | 0.84 | 0.16 |

| Turn family/friends/children against you | 215 | 0.48 (0.94) | 0.84 | 0.70 | 0.30 | 0.82 | 0.67 | 0.33 |

| Keep you from seeing or talking to family | 216 | 0.33 (0.78) | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.10 | – | – | – |

| Blamed their violent behaviour on you | 216 | 0.61 (1.03) | 0.94 | 0.89 | 0.11 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.08 |

| Told you that you were crazy | 215 | 0.60 (1.00) | 0.94 | 0.88 | 0.12 | – | – | – |

| Told you that no one would ever want you | 214 | 0.44 (0.93) | 0.93 | 0.87 | 0.13 | – | – | – |

| Stopped from seeing female friends | 216 | 0.36 (0.81) | 0.92 | 0.84 | 0.16 | – | – | – |

| Stopped you from connecting to Aboriginality | 216 | 0.21 (0.69) | 0.90 | 0.81 | 0.19 | 0.88 | 0.78 | 0.22 |

| Got jealous/wild if talked to male friends | 216 | 0.56 (1.01) | 0.93 | 0.86 | 0.14 | 0.91 | 0.83 | 0.17 |

| Made you feel bad about being Aboriginal | 216 | 0.12 (0.50) | 0.74 | 0.55 | 0.45 | – | – | – |

| Got wild when you dressed up/makeup on | 215 | 0.30 (0.80) | 0.91 | 0.82 | 0.18 | – | – | – |

| Threatened to hurt you/family/pets | 215 | 0.32 (0.76) | 0.83 | 0.69 | 0.31 | 0.84 | 0.71 | 0.30 |

| Physical partner violence | χ2(35) = 62.93, p=0.003, RMSEA=0.06 (0.04, 0.09), CFI=1.00, TLI=1.00, SRMR=0.07 | χ2(9) = 14.56, p=0.104, RMSEA=0.05 (0.00, 0.10), CFI=1.00, TLI=1.00, SRMR=0.07 | ||||||

| Slapped or hit you | 211 | 0.30 (0.72) | 0.95 | 0.91 | 0.09 | – | – | – |

| Shook you | 216 | 0.26 (0.72) | 0.94 | 0.89 | 0.11 | – | – | – |

| Pushed, grabbed or shoved you | 216 | 0.35 (0.78) | 0.97 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.97 | 0.93 | 0.07 |

| Hit or tried to hit you with something | 216 | 0.30 (0.73) | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.10 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.10 |

| Kicked you, bit you or punched you | 215 | 0.23 (0.65) | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.02 | – | – | – |

| Used a knife/gun/other weapon | 213 | 0.10 (0.43) | 0.86 | 0.74 | 0.26 | 0.85 | 0.73 | 0.27 |

| Flogged you | 215 | 0.15 (0.57) | 0.95 | 0.91 | 0.09 | – | – | – |

| Stopped you from leaving the house | 214 | 0.30 (0.76) | 0.91 | 0.83 | 0.17 | 0.92 | 0.84 | 0.16 |

| Forced you to do something sexually | 216 | 0.09 (0.42) | 0.60 | 0.36 | 0.64 | 0.67 | 0.45 | 0.56 |

| Smashed up or destroyed your things | 216 | 0.39 (0.84) | 0.88 | 0.77 | 0.24 | 0.90 | 0.81 | 0.19 |

| Financial partner violence | χ2(20) = 24.37, p=0.227, RMSEA=0.03 (0.00, 0.07), CFI=1.00, TLI=1.00, SRMR=0.04 | χ2 (9) = 5.41, p=0.798, RMSEA=0.00 (0.00, 0.05), CFI=1.00, TLI=1.00, SRMR=0.01 | ||||||

| Refused to contribute to family finances | 215 | 0.52 (1.01) | 0.88 | 0.77 | 0.23 | 0.88 | 0.77 | 0.23 |

| Took money you needed for something else | 216 | 0.41 (0.86) | 0.94 | 0.88 | 0.12 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.10 |

| Got wild if you spent money on yourself | 214 | 0.26 (0.73) | 0.89 | 0.80 | 0.20 | 0.89 | 0.79 | 0.21 |

| Stopped from earning your own money | 215 | 0.16 (0.59) | 0.86 | 0.74 | 0.26 | – | – | – |

| Got you to pay their bills | 216 | 0.31 (0.78) | 0.91 | 0.82 | 0.18 | 0.91 | 0.83 | 0.17 |

| Took your money made worry about not having enough | 216 | 0.34 (0.83) | 0.97 | 0.94 | 0.05 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.06 |

| Made you put the bills in your name | 216 | 0.13 (0.55) | 0.75 | 0.56 | 0.44 | – | – | – |

| Made you ask for money for bills, food or kids | 216 | 0.25 (0.70) | 0.85 | 0.72 | 0.28 | 0.84 | 0.70 | 0.30 |

CFI, Comparative Fit Index; RMSEA, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation; SRMR, Standardized Root Mean Square Residual; TLI, Tucker-Lewis Index.

As shown in table 4, the AEPV subscales showed excellent internal reliability (≥0.9). The observed scores covered the complete scale range for emotional and financial IPV scales (0–18), while the highest score for physical IPV was 15. Mean scales scores ranged from 1.5 for physical IPV to 2.8 for emotional IPV.

Table 4.

Aboriginal Women’s Experiences of Partner Violence Scale (AEPVS)—items, prevalence and scale psychometrics (n=216)

| Scales (scoring) items |

Scale range | n (%) | Cronbach α |

Score range |

Mean scale score (SD) | Mean total AEPV score (SD) |

| Emotional partner violence (score ≥3) | 0–18 | 69 (31.9) | 0.90 | 0–18 | 2.8 (4.4) | 18.7 (12.3) |

| Told you that you are stupid or no good | ||||||

| Turn family/friends/children against you | ||||||

| Blamed their violent behaviour on you | ||||||

| Stopped you from connecting to Aboriginality | ||||||

| Got jealous/wild if talked to male friends | ||||||

| Threatened to hurt you/family/pets | ||||||

| Physical partner violence (score ≥1) | 0–18 | 63 (29.2) | 0.87 | 0–15 | 1.5 (3.2) | 19.3 (12.8) |

| Pushed, grabbed or shoved you | ||||||

| Hit or tried to hit you with something | ||||||

| Used a knife/gun/other weapon | ||||||

| Stopped you from leaving the house | ||||||

| Forced you to do something sexually | ||||||

| Smashed up or destroyed your things | ||||||

| Financial partner violence (score ≥2) | 0–18 | 62 (28.7) | 0.91 | 0–18 | 2.1 (4.1) | 19.3 (12.8) |

| Refused to contribute to family finances | ||||||

| Took money you needed for something else | ||||||

| Got wild if you spent money on yourself | ||||||

| Got you to pay their bills | ||||||

| Took your money made worry about not having enough | ||||||

| Made you ask for money for bills, food or kids | ||||||

| Total AEPVS score | 0–57 | 84 (38.9%) | 0.96 | 1–54 | 6.4 (11.0) | 16.0 (12.5) |

*Mean total AEPVS score for women reporting partner violence

Overall, 38.9% of women reported experiences of IPV in the previous 12 months. Almost one in three were scored as experiencing physical IPV (29.2%), emotional IPV (31.9%) or financial IPV (28.7%). Each of the different types of IPV had a total mean score of close to 20 suggesting a similar frequency of behaviours within each scale. A majority of the women experiencing partner violence reported multiple types of violence (65/84, 77.4%) and correspondingly, few women reported emotional, financial or physical abuse alone (19/84, 22.6%).

Women who had experienced IPV in the previous 12 months indicated that they had done a variety of things to protect themselves and stay strong (table 5). More than half had taken their children to stay with family or friends (55.4%) or called police (51.8%), and just over one in three (37.3%) had taken out an intervention order. Women more commonly talked to family and friends (67.5%) than talked to a health professional. Just under one in three (31.3%) had talked to a local doctor and one in four (26.5%) had talked to a counsellor or psychologist.

Table 5.

What women experiencing partner violence did to protect themselves and stay strong (n=84)

| Recent intimate partner violence, no. (%) | |

| Talked to family about it | 56 (67.5) |

| Talked to friend about it | 50 (60.2) |

| Left house | 49 (59.0) |

| Took kids to stay with family/friends | 46 (55.4) |

| Phoned police | 43 (51.8) |

| Got intervention order | 31 (37.3) |

| Changed phone number | 30 (36.1) |

| Talked to doctor about it | 26 (31.3) |

| Talked to counsellor/psychologist about it | 22 (26.5) |

| Talked to Aboriginal health worker about it | 14 (16.9) |

| Called domestic violence telephone line | 14 (17.1) |

| Stayed in women’s shelter | 10 (12.3) |

Discussion

The 18-item AEPVS is the first co-designed, culturally adapted, multidimensional measure of partner violence for Aboriginal women. Initial construct validity and reliability testing indicates that it provides a robust measure of Aboriginal women’s experiences of physical, emotional and financial partner violence. The adapted measure (see online supplemental appendix 1) was developed with extensive input from Aboriginal women and builds on a co-designed programme of research conducted in collaboration with the Aboriginal Health Council of South Australia. Aboriginal governance was provided by an Aboriginal Advisory Group that guided the work of the research team at every stage of the co-design process. This included critical input into decisions regarding items included in the initial version of the adapted measure, advice on the inclusion of words in Aboriginal languages, guidance on ways for the research team to facilitate cultural safety for research participants and Aboriginal researchers and providing approval for the final version of the measure.

bmjopen-2021-059576supp001.pdf (118.1KB, pdf)

Very few women participating in Wave 2 follow-up opted not to complete the measure and the number of individual items skipped by research participants was minimal. The iterative process used for co-designing the adapted measure allowed for multiple stages of feedback and refinement. Importantly, the research team tested several versions of the preamble to the section of the questionnaire asking about partner violence before settling on the final wording. Women were also made aware, during the consent process, that the questionnaire included a section asking about family violence and other things that might be happening in their lives. All contact with women in the study was made by Aboriginal researchers, who in some cases were known to women from the baseline study. Reconnecting with women and building relationships of trust was an important part of the research process led by Aboriginal members of the team. This is a major strength of the study and is likely to have contributed to participation of women who may otherwise have been reluctant to take part. Embedding the development of the AEPVS within follow-up of an existing cohort allowed us to build on established relationships and processes designed to build trust and confidence in research processes.25 The community connections of Aboriginal research team members were central to our success in reconnecting with families. At the same time, the research team was mindful of the need to maintain confidentiality for families in the study. Where members of the team had close connections with families, contact was generally initiated by another member of the team and/or participants were offered the choice of meeting with another team member.

The current phase of the research also built on our track record of using results to advocate for improvements to services to benefit Aboriginal communities.36 Approximately a quarter of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women who gave birth in South Australia over a 2-year period (mid 2011 to mid 2013) took part in Wave 1.25 Evidence of extreme social disadvantage in the cohort is apparent in the high proportion of women eligible for a government healthcare card at both Wave 1 and Wave 2 follow-up. The geographical distribution of the cohort, age of women at the time of giving birth to the study children and high proportion of women who were not living with a partner at Wave 2 follow-up reflect population characteristics of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families in South Australia.37 Both the diversity and representativeness of the women participating in validation of the AEPVS contribute to the robustness of the findings.

Other strengths of the study include: well-established Aboriginal governance processes guiding decision-making at all stages of the research; and use of participatory methods to engage Aboriginal women living in urban, regional and remote communities in South Australia in co-design of the adapted measure. The research team worked with guidance of the Aboriginal Advisory Group and Aboriginal women participating in discussion groups to ensure content validity and cultural acceptability of the AEPVS and the cultural safety of processes used by the research team to engage women in the study and seek their feedback. Importantly, women were advised why the questions on partner violence were being asked and how the information gathered would be used. Questions asking about experiences of partner violence were followed by a strengths-based question asking about the things women did to protect themselves and stay strong. In taking these steps, our aim was to minimise the potential for women to feel judged for things that had happened to them, to acknowledge the many things that women do to manage complex circumstances surrounding partner violence and to reduce the risk of participation in the study causing harm or distress to women. The research team were trained and supported to respond to women who either sought support or conveyed particularly complex circumstances.

While we were not able to compare results of the measure with a ‘gold standard’ (given the lack of availability of other culturally validated measures), the information women provided about the actions they had taken to protect themselves confirm that a significant proportion of women categorised as experiencing IPV had sought assistance from other family members, taken children to stay with family or friends, called police, changed phone numbers or obtained an intervention order. While the sample is both geographically and culturally diverse—including women from urban, regional and remote areas of South Australia and over 35 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander language/clan groups (including groups from other Australian jurisdictions)—the results may not apply directly to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities in other jurisdictions or to other Indigenous populations. Finally, the adapted measure was developed and tested with women of childbearing age. The youngest woman in the study to complete the measure was 20 and the oldest was 49 at the time of Wave 2 follow-up. Further adaptation may be required for younger and older Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, and for use in other jurisdictions.

The immediate purpose of developing a culturally adapted measure of Aboriginal women’s experiences of partner violence was to improve understanding of the health consequences of partner violence for Aboriginal women and children, and build knowledge about cultural and community level factors which may moderate the impacts of partner violence in Aboriginal families. Future papers will explore these issues contributing to a small body of evidence bringing an Indigenous lens and more granulated understanding to the context and impact of IPV within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.6 38 39

Concurrent with the conduct of the study, a revised short-form of the CAS was developed drawing on data from five Canadian studies and feedback from an international panel of experts. The study, published while our study was underway, identified gaps in the original measure, including the lack of items on financial abuse, use of threats and choking.40 It is important to recognise that no measure can be comprehensive and that methods of abuse will vary across populations and contexts.

Conclusion

The AEPVS is the first co-designed, multidimensional measure of Aboriginal women’s experience of physical, emotional and financial IPV with demonstrated cultural acceptability, construct validity and reliability within the setting of an Aboriginal-led, community-based and governed research project. Culturally safe research methods and tools are important for generating the evidence needed to inform co-design, implementation and evaluation of tailored strategies to support families impacted by partner violence. The AEPVS cannot be separated from the processes surrounding its culturally safe use. Validation of the measure in other settings and populations will need to incorporate processes for community governance and tailoring of research process to local community contexts.

The Aboriginal Women’s Experiences of Partner Violence Scale (AEPVS) may not be reproduced without permission. There is no fee to use this scale, but permission must be obtained from the Aboriginal Families Study Aboriginal Advisory Group Executive Team before use. Please contact: Karen Glover (karen.glover@sahmri.com) or Stephanie Brown (stephanie.brown@mcri.edu.au).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors respectfully acknowledge the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Custodians of the Lands and Waters of Australia. We would like to acknowledge members of the Aboriginal Advisory Group who guided all stages of the study, including interpretation of findings, and members of the research team (additional to the authors) who contributed to data collection, all women and families taking part in the study and the many agencies that assisted us to reconnect with families. Finally, we would like to thank Professor Kelsey Hegarty for permission to adapt the Composite Abuse Scale and for her helpful advice at several stages of the study.

Footnotes

Contributors: KG, SJB, DW, DG and RG conceptualised the study. SJB and KG wrote the study protocol. KG, CL, DW, AN, SJB and DG co-designed the procedures for cultural adaptation of the Composite Abuse Scale measure. KG and AN conducted discussion groups and facilitated pretesting of the draft follow-up questionnaire. KG, AN and DW facilitated Wave 2 follow-up. DG and RG undertook psychometric analyses. SJB, DG and KG co-wrote the manuscript. All authors (KG, CL, AN, DW, YC, DG, RG, SJB) contributed to interpretation of data, reviewed earlier versions of the manuscript and approved the final version. KG and AN facilitated discussion groups. KG, DW and AN led the fieldwork team undertaking data collection. DG and RG conducted quantitative analyses; KG, CL, AN, DW, YC, SJB, DG, RG and members of the Aboriginal Advisory Group interpreted the data; SJB, DG, RG and KG drafted the paper. All authors critically revised the paper, approved the manuscript to be published and are accountable for the accuracy and integrity of the work. SB is responsible for the overall content as guarantor.

Funding: This study was supported by two National Health and Medical Research Council project grants #1004395 and #1105561 and SA Health. Research at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute is supported by the Victorian Government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Program.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

No data are available. Data cannot be shared publicly per the agreement between study investigators and the Aboriginal Health Council of South Australia to maximise participant privacy and confidentiality and protect Indigenous data sovereignty. Data sharing is subject to approval by the study’s Aboriginal Advisory Group and Investigator team. Applications will be considered in context of papers in progress, compliance with conditions of ethics approval and consent, and potential benefits to Indigenous communities. Interested researchers are invited to submit a request via the Aboriginal Families Study (afs@mcri.edu.au) or to contact the Principal Investigator, Professor Stephanie Brown (stephanie.brown@mcri.edu.au)

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the Aboriginal Human Research Ethics Committee of South Australia (04.09.290; 04.17.737); the South Australian Department of Health (298/06/2012); Women’s and Children’s Health Network, Adelaide (2335/12/13); the Lyell McEwin Hospital (2010181), Adelaide; and the Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne (29076A, 36186). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and nonpartner sexual violence. W: World Health Organization, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown SJ, Conway LJ, FitzPatrick KM, et al. Physical and mental health of women exposed to intimate partner violence in the 10 years after having their first child: an Australian prospective cohort study of first-time mothers. BMJ Open 2020;10:e040891. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raphael B, Swan P, Martinek N. Intergenerational Aspects of Trauma for Australian Aboriginal People. In: Danieli Y, ed. International Handbook of multigenerational legacies of trauma. Boston, MA: Springer, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Healing Foundation . Our healing our solutions. Canberra: Healing Foundation, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atkinson J. Trauma trails, recreating song lines: the transgenerational effects of trauma in Indigenous Australia. Spinifex, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Langton MSK, Eastman T, O'Neill L. Improving family violence legal and support services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. Sydney: ANROWS, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devries KM, Mak JY, Bacchus LJ, et al. Intimate partner violence and incident depressive symptoms and suicide attempts: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001439. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellsberg M, Jansen HAFM, Heise L, et al. Intimate partner violence and women's physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence: an observational study. Lancet 2008;371:1165–72. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60522-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gartland D, Conway LJ, Giallo R, et al. Intimate partner violence and child outcomes at age 10: a pregnancy cohort. Arch Dis Child 2021;106:1066–74. 10.1136/archdischild-2020-320321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bair-Merritt MH, Blackstone M, Feudtner C. Physical health outcomes of childhood exposure to intimate partner violence: a systematic review. Pediatrics 2006;117:e278–90. 10.1542/peds.2005-1473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rivas C, Ramsay J, Sadowski L. Advocacy interventions to reduce or eliminate violence and promote the physical and psychosocial well-being of women who experience intimate partner abuse. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;12:CD005043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hameed M, O'Doherty L, Gilchrist G, et al. Psychological therapies for women who experience intimate partner violence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020;7:CD013017. 10.1002/14651858.CD013017.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia 2018. Canberra: AIHW, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spangaro J, Herring S, Koziol-Mclain J, et al. 'They aren't really black fellas but they are easy to talk to': Factors which influence Australian Aboriginal women's decision to disclose intimate partner violence during pregnancy. Midwifery 2016;41:79–88. 10.1016/j.midw.2016.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fanslow JL, Robinson EM. Help-seeking behaviors and reasons for help seeking reported by a representative sample of women victims of intimate partner violence in New Zealand. J Interpers Violence 2010;25:929–51. 10.1177/0886260509336963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woolhouse H, Gartland D, Papadopoullos S, et al. Psychotropic medication use and intimate partner violence at 4 years postpartum: results from an Australian pregnancy cohort study. J Affect Disord 2019;251:71–7. 10.1016/j.jad.2019.01.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ford-Gilboe M, Varcoe C, Noh M, et al. Patterns and predictors of service use among women who have separated from an abusive partner. J Fam Violence 2015;30:419–31. 10.1007/s10896-015-9688-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization/London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine . Preventing intimate partner and sexual violence against women: taking action and generating evidence. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.García-Moreno C, Hegarty K, d'Oliveira AFL, et al. The health-systems response to violence against women. Lancet 2015;385:1567–79. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61837-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.State of Victoria . Royal Commission into family violence: summary and recommendations, 2014-2016. [Google Scholar]

- 21.State of Victoria . Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System, Final Report, Summary and recommendations (document 1 of 6). 6, 2018: 21. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hegarty K, Sheehan M, Schonfeld C. A multidimensional definition of partner abuse: development and preliminary validation of the composite abuse scale. J Fam Violence 1999;14:399–415. 10.1023/A:1022834215681 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hegarty K, Bush R, Sheehan M. The composite abuse scale: further development and assessment of reliability and validity of a multidimensional partner abuse measure in clinical settings. Violence Vict 2005;20:529–47. 10.1891/vivi.2005.20.5.529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buckskin M, Ah Kit J, Glover K, et al. Aboriginal families study: a population-based study keeping community and policy goals in mind right from the start. Int J Equity Health 2013;12:41. 10.1186/1475-9276-12-41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weetra D, Glover K, Miller R, et al. Community engagement in the Aboriginal families study: strategies to promote participation. Women Birth 2019;32:72–9. 10.1016/j.wombi.2018.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson MP BK. Hertz MF measuring intimate partner violence victimization and Perpetration: a compendium of assessment tools. Atlanta (GA): centers for disease control and prevention, National center for injury prevention and control, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taft AJ, Hooker L, Humphreys C, et al. Maternal and child health nurse screening and care for mothers experiencing domestic violence (move): a cluster randomised trial. BMC Med 2015;13:150. 10.1186/s12916-015-0375-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hegarty K, O'Doherty L, Taft A, et al. Screening and counselling in the primary care setting for women who have experienced intimate partner violence (weave): a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2013;382:249–58. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60052-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wathen CN, Tanaka M, MacGregor JCD, et al. Trajectories for women who disclose intimate partner violence in health care settings: the key role of abuse severity. Int J Public Health 2016;61:873–82. 10.1007/s00038-016-0852-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rasmussen V, Steel Z, Spangaro J, et al. Investigating the prevalence of intimate partner violence victimisation in women presenting to the emergency department in suicidal crisis. Emerg Med Australas 2021;33:703–10. 10.1111/1742-6723.13714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tutty LM, Radtke HL, Thurston WEB, et al. The mental health and well-being of Canadian Indigenous and non-Indigenous women abused by intimate partners. Violence Against Women 2020;26:1574–97. 10.1177/1077801219884123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu Li‐tze, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 1999;6:1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shevlin M. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis in clinical and health psychology. In: A Handbook of research methods for clinical and health psychology. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 34.DeVon HA, Block ME, Moyle-Wright P, et al. A psychometric toolbox for testing validity and reliability. J Nurs Scholarsh 2007;39:155–64. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00161.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kline T. Psychological testing: a practical approach to design and evaluation. London: SAGE Publications, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Middleton P, Bubner T, Glover K, et al. 'Partnerships are crucial': an evaluation of the Aboriginal family birthing program in South Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health 2017;41:21–6. 10.1111/1753-6405.12599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pregnancy Outcome Unit . Pregnancy outcome in South Australia 2018. Adelaide: Prevention and Population Health Directorate, Wellbeing SA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cripps K, Bennett CM, Gurrin LC, et al. Victims of violence among Indigenous mothers living with dependent children. Med J Aust 2009;191:481–5. 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb02909.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andrews S. Cloaked in strength – how possum skin cloaking can support Aboriginal women’s voice in family violence research. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 2020;16:108–16. 10.1177/1177180120917483 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ford-Gilboe M, Wathen CN, Varcoe C, et al. Development of a brief measure of intimate partner violence experiences: the Composite Abuse Scale (Revised)-Short Form (CASR-SF). BMJ Open 2016;6:e012824. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-059576supp001.pdf (118.1KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

No data are available. Data cannot be shared publicly per the agreement between study investigators and the Aboriginal Health Council of South Australia to maximise participant privacy and confidentiality and protect Indigenous data sovereignty. Data sharing is subject to approval by the study’s Aboriginal Advisory Group and Investigator team. Applications will be considered in context of papers in progress, compliance with conditions of ethics approval and consent, and potential benefits to Indigenous communities. Interested researchers are invited to submit a request via the Aboriginal Families Study (afs@mcri.edu.au) or to contact the Principal Investigator, Professor Stephanie Brown (stephanie.brown@mcri.edu.au)