Abstract

The purpose of this study was to compare the quality of feeding assistance provided by trained non-nursing staff with care provided by certified nursing assistants (CNAs). Research staff provided an 8-hr training course that met federal and state requirements to non-nursing staff in five community long-term care facilities. Trained staff were assigned to between-meal supplement and/or snack delivery for 24 weeks. Using standardized observations, research staff measured feeding assistance care processes between meals across all study weeks. Trained staff, nurse aides, and upper level staff were interviewed at 24 weeks to assess staff perceptions of program impact. Trained staff performed significantly better than CNAs for 12 of 13 care process measures. Residents also consumed significantly more calories per snack offer from trained staff (M = 130 ± 126 [SD] kcal) compared with CNAs (M = 77 ± 94 [SD] kcal). The majority of staff reported a positive impact of the training program.

Keywords: nutrition/weight loss, feeding assistant regulation, staff training, long-term care

Introduction

Inadequate food and fluid intake among long-term care (LTC) residents is common and contributes to poor health outcomes such as unintentional weight loss, dehydration, hospitalization, and death (Agarwal, Ferguson, & Banks, 2013; Blaum, Fries, & Fiatarone, 1995; Ferguson, O’Connor, & Crabtree, 1993; Thomas, Cooney, & Fried, 2013). Poor dietary intake is related to physical, cognitive, behavioral, and environmental factors in the LTC setting, including insufficient or inadequate staff assistance (Crogan & Shultz, 2000; Kayser-Jones & Schell, 1997; Simmons, 2007). Improvements in mealtime assistance and staff offers of additional calories between meals both have been shown to be efficacious approaches to improve LTC residents’ dietary intake. However, both of these nutritional interventions also require significantly more staff time relative to usual LTC practices (Simmons et al., 2015, 2008; Simmons, Osterweil, & Schnelle, 2001; Simmons & Schnelle, 2004). Specifically, optimal mealtime assistance requires an average of 35 min or more per resident meal. In contrast, many LTC residents receive an average of less than 10 min of staff assistance during meals. Similarly, between-meal delivery of snacks and supplements requires an average of 10 to 15 min per resident 2 to 3 times daily (Simmons et al., 2015, 2008; Simmons et al., 2001; Simmons & Schnelle, 2004). However, standardized observations of usual LTC practices have shown that between-meal delivery of snacks and/or supplements occurs, on average, only once per resident per day and LTC staff spends less than 2 min per offer to encourage consumption (Simmons et al., 2015; Simmons & Patel, 2006; Simmons & Schnelle, 2004).

National data reveal that the majority of LTC residents require some level of staff assistance for eating. Specifically, 23% of LTC residents are rated by staff as requiring total or extensive assistance with eating, whereas an additional 51% need limited assistance or supervision (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS], HHS, 2015a). The amount of staff time required for optimal feeding assistance care combined with a majority of LTC residents in need of such help creates a high demand for staffing resources to deliver care effectively multiple times per day. Traditionally, both mealtime and between-meal tasks have been the primary responsibilities of Certified Nursing Assistants (CNAs; Crogan & Shultz, 2000; Simmons et al., 2001). However, studies suggest that this heavy reliance on CNAs can introduce barriers to consistent, high-quality feeding assistance care. For example, CNAs have a high 3-month turnover rate (Temple, Dobbs, & Andel, 2009) and the highest annual turnover rate of all types of LTC staff (Bostick, Rantz, Flesner, & Riggs, 2006; Castle & Engberg, 2005). Moreover, many facilities may not have enough CNA staff to provide adequate care to all residents, with a national average of 2.47 CNA hours per resident per day (CMS, HHS, 2015b), though studies suggest that a minimum of 2.8 to 3.2 CNA hours per resident per day is required to meet all of residents’ daily care needs, including their feeding assistance care needs (Schnelle et al., 2004). Second, CNAs have self-reported that they often lack sufficient time to adequately complete all of the daily care tasks for their assigned residents (Crogan & Shultz, 2000; Kayser-Jones & Schell, 1997). Because multiple studies have demonstrated that optimal feeding assistance care is time-consuming and greatly exceeds the amount of time CNAs typically spend on this care (Simmons, 2007; Simmons et al., 2001; Simmons & Schnelle, 2004, 2006a), other staffing models beyond a sole reliance on CNA hours need to be considered to augment this critical aspect of daily care.

In light of data suggesting that many LTC residents receive sub-optimal feeding assistance care quality and that low CNA staffing levels may contribute to this problem (Schnelle, Cretin, Saliba, & Simmons, 2000; Schnelle et al., 2004; Simmons et al., 2001; Simmons & Schnelle, 2004), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued a new federal regulation in 2003 “Requirements for Paid Feeding Assistants in Long Term Care Facilities” (CMS C.F.R. §483.16), which allows facilities to hire single task workers or cross train existing non-nursing staff to assist with feeding during and/or between meals. The federal regulation requires staff to complete a minimum of 8 hr of training by a licensed nurse, complete a competency test (written or performance based), be assigned residents without complicated feeding needs (i.e., history of aspiration), and be supervised by a licensed nurse (CMS, HHS, 2003). To date, the majority of states have adopted this regulation with some states also increasing the hours or criteria necessary for training (Division of Health Policy Management, School of Public Health, University of Minnesota, 2012).

There were a number of concerns when CMS C.F.R. §483.16 was initially enacted in 2003. For example, stakeholders and LTC consumer groups expressed apprehension about the adequacy of the required training and the potential safety risks posed by non-nursing staff providing feeding assistance (Kapp, 2013; Remsburg, 2004; Simmons et al., 2007). As part of a CMS-sponsored national evaluation in 2007, trained staff performed as well or better than indigenous CNAs during mealtime care provision in a sample of facilities with active training programs (Simmons et al., 2007). To date, few additional studies have examined the potential use of trained staff to improve feeding assistance care quality; thus, sparse data exist related to how well received this practice is by non-nursing staff who complete training as well as their nurse aide and licensed nurse counterparts within the same facilities. The current study was conducted as part of a larger randomized controlled trial to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of using trained non-nursing staff for between-meal caloric supplementation for nutritionally at-risk residents. The primary outcomes from the larger study are reported separately (Simmons et al. 2017). The purpose of this study was to directly compare the quality of feeding assistance provided by trained staff with the same care provided by indigenous CNAs and also examine staff perceptions of the impact of the training program. The following research questions were addressed:

Research Question 1: How do trained staff compare to indigenous CNAs on the quality of between-meal feeding assistance care processes based on standardized observations?

Research Question 2: What are the perceptions of trained staff related to their feeding assistant care role and their competency in this role based on structured interviews?

Research Question 3: What are the perceptions of CNAs and upper level management staff related to the impact and competency of non-nursing staff to provide feeding assistance care based on structured interviews?

Method

Participants and Setting

Long-stay residents were recruited for the larger study from five community facilities, four of which were for-profit, housing a total of 507 residents. Recruitment and data collection procedures for this study were approved by the university-affiliated institutional review board. The CNA hours per resident per day ranged from 0.97 to 2.37 hr based on the most recent survey data for the five participating facilities, which was lower than the concurrent national average of 2.47 hr (CMS, HHS, 2015b). Resident inclusion criteria required residents to be long-stay and at nutritional risk, as defined by a physician or dietitian order for caloric supplementation either in the form of an oral liquid nutrition supplement (e.g., Resource®, Boost®) and/or staff offers of additional foods and beverages (i.e., snacks) between regularly scheduled meals. Residents with an order for hospice services, enteral or parenteral feeding, or a history of aspiration based on LTC medical record documentation were excluded from participation. The exclusion criteria were aligned with CMS C.F.R. §483.16, which states that trained staff cannot assist residents with medically complicated swallowing issues, although a diagnosis of dysphagia and/or a modified textured diet does not preclude someone from being assisted by trained staff.

As part of the larger study, written consent was obtained for 148 of 228 eligible residents (64.9%) or his or her surrogate. A total of 20 residents were lost from the study prior to completing baseline assessments due to death (10), transfer out of facility (3), transfer to hospice (1), feeding tube insertion (1), or discontinuation of their caloric supplementation order (5). After randomization, 63 residents were assigned to the intervention group, for whom between-meal assistance could be provided by either trained staff or CNAs. The remaining 65 residents were assigned to a usual care control group. The data reported in this study are specific to those randomized to the intervention group to allow a comparison of nutritional care quality between trained staff and CNA staff for the same residents. Of the 63 residents randomized to the intervention group, two were lost in the first study month; thus, a total of 61 residents comprised the sample for this study. The characteristics of the residents who participated in the larger study (n = 148) and the intervention group, which was analyzed for the purposes of this study (N = 61), are typical of LTC residents in prior similar studies as part of which nutritionally at-risk residents were recruited for study participation (Simmons et al., 2015, 2008; Simmons & Schnelle, 2004). Specifically, participants were predominately female (85.2%) and non-Hispanic White (68.3%), with an average age of 85.6 (±9.6) years and an average length of LTC residency of 2.8 (±2.6) years. Most (72.1%) had a dementia diagnosis and/or some type of modified diet orders (65.6%), and 95.2% were rated by LTC staff as requiring assistance to eat (supervision to total dependence) based on medical record documentation.

Staff Training

During baseline, existing non-nursing staff employed within each of the five LTC sites was invited to participate in an 8-hr training curriculum that met both the federal and state requirements. Upper level management within each site (administrator, director of nursing, staff developer) was allowed to guide the recruitment efforts for non-nursing staff to participate in training. Three facilities required participation from certain departments (e.g., housekeeping, nutrition services, social activities), whereas the remaining two facilities simply asked for non-nursing personnel to volunteer for training. A multidisciplinary research team consisting of a geriatric nurse practitioner, behavioral psychologist, registered dietitian, and social worker led the training, which included the required elements defined within the Paid Feeding Assistant Regulation, CMS §483.16 (CMS, HHS, 2003).

Upon completion of the 8-hr training course, each trainee completed a 14-item performance skills test (see the appendix). The federal regulation requires either a written or performance-based competency test. As part of the performance evaluation, research staff directly observed each trainee during feeding assistance care delivery and provided feedback about their performance until each trainee was able to successfully perform all of the skills shown in the appendix. After successful achievement in the skills test (i.e., completion of 100% of the items), trained staff were then assigned to assist designated residents (i.e., N = 61 assigned to the intervention group in the larger study) with between-meal snack and supplement delivery twice per day (morning and afternoon), 5 days per week (Monday - Friday), for 24 consecutive weeks.

Standardized Observations of Trained Staff and CNAs During Between-Meal Care Provision

Each weekday throughout the 24 study weeks during the morning and afternoon periods (1.5 hr per observation period), research staff conducted standardized observations of trained staff and all other LTC staff members (e.g., CNAs, licensed nurses) who provided feeding assistance care between meals to intervention group participants. Prior to these observations, research staff members were trained in conducting standardized observations of feeding assistance care process measures until interrater reliability was achieved at .80 or higher for each data element. The care process measures shown in Table 2 align with common dietary and dignity federal regulations evaluated annually by federal and state surveyors, commonly known as F-tags. Surveyors can issue deficiencies, as defined by F-tags, for care that reflects substandard quality. There are a total of 190 possible deficiencies across 16 categories, one of which is dietary services (Levinson, 2008). Furthermore, prior studies have shown that the consistent delivery of these feeding assistance care process measures will result in significant gains in caloric intake both during and between meals (Simmons et al., 2015, 2008). The aim of the data collection protocol was to conduct four between-meal observations per resident (N = 61) per week for each of the 24 study weeks, to yield a total of 96 possible observations per participant. However, the number of successfully completed observations varied weekly due to a between-meal snack not being offered by any type of staff (i.e., trained staff, CNA, or other) during an observation period, resident factors (e.g., hospitalization, illness, death, feeding tube insertion, transfer out of facility), and holidays during which research personnel was not present at the LTC site.

Table 2.

Between-Meal Care Process Comparisons: Trained Staff Versus CNA Care Episodes.

| Federal tag | Care process | Trained staff episodes (n = 3,046) % (n) or M (SD) | CNA episodes (n = 863) % (n) or M (SD) | χ2 or t test value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greeting | ||||

| F371 | Wash hands | 57.0 (1,517) | 3.1 (26) | 742.08*** |

| F241 | Greet resident by name | 97.1 (2,957) | 89.0 (767) | 99.48*** |

| F241 | Introduce themselves to resident | 97.0 (2,949) | 92.6 (797) | 35.37*** |

| Offer choices | ||||

| F325, F327 | Fluids | 42.4 (1,248) | 5.2 (45) | 411.09*** |

| F325, F366 | Foods | 60.0 (1,760) | 9.8 (84) | 669.20*** |

| Alternative if eating < 50% | 13.1 (61) | 4.9 (12) | 12.02** | |

| Second serving | 13.5 (240) | 3.8 (17) | 33.43*** | |

| Provide assistance | ||||

| F310 | Ensure resident sitting upright | 85.9 (324) | 77.2 (142) | 6.76** |

| F241 | Staff seated across from resident | 71.0 (336) | 49.8 (119) | 31.07*** |

| F312 | Staff provided manageable bites/drinks | 98.9 (550) | 97.3 (257) | 2.84 |

| F241 | Social stimulation provided | 84.6 (2,257) | 63.4 (519) | 173.92*** |

| F241, F310 | Verbal cueing | 90.5 (2,115) | 76.9 (596) | 95.15*** |

| F310 | Spend at least 5 min (or until finished) | 41.3 (985) | 32.4 (256) | 19.65*** |

| Per resident per episode | ||||

| Average assistance time (minutes) | 2.57 (±3.32) | 1.77 (±2.40) | 6.64*** | |

| Average calories consumed (kcals) | 130 (±126) | 77 (±94) | 11.63*** |

Note. CNA = certified nursing assistant.

p ≤ .01.

p < .001.

Each of 13 care process measures were rated by research personnel as yes, no, or not applicable. For example, staff were not expected to offer a second helping (see the appendix, Item 12) if the resident did not consume 100% of the first serving during a between-meal care delivery episode. After completion, an overall score was calculated per care delivery episode based on the total number of items marked as “yes” (numerator) divided by all valid answers (total number of “yes” + total number of “no,” excluding those marked as “not applicable”).

During each between-meal observation period, research staff documented the total amount of time (minutes and seconds) that LTC staff spent providing any type of assistance (e.g., verbal encouragement or cueing, physical help, opening containers) to the resident to promote consumption of the served foods, beverages, and liquid supplements. Research staff also documented the amount consumed of each served item per snack episode. The total amount of calories consumed from snacks was estimated based on the caloric information per serving, which was available from the facility kitchen or the printed information on the container, and an estimate of the amount consumed using a percentage scale for food items (0%−100%) and ounces consumed for fluids. Prior studies have shown that standardized observations yield valid estimates of intake (Simmons et al., 2008, 2001; Simmons & Reuben, 2000; Simmons & Schnelle, 2004).

Staff Interviews

To further examine potential concerns about the use and impact of trained staff, research staff interviewed multiple types of staff following 6 months of program implementation. All interviews followed a structured format that included both closed and open-ended questions similar to those used in prior studies (Bertrand et al., 2011; Simmons et al., 2007). In addition, staff participation in the interview was voluntary and conducted individually, in-person, and in a private area within the facility.

Following 6 months after training, trainees were asked nine standardized questions related to their feeding assistant job role and their comfort level in this role. Also at 6 months, day shift CNAs (7:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m.) were asked 11 standardized questions that paralleled the trainee interview to include direct questions about their perception of the competence of trained staff. In addition, upper level staff (e.g., administrator, director of nursing, dietitian) were interviewed following 6 months of program implementation to evaluate their perceptions of program impact, concerns, and plans for the continued use of trained staff to assist with between-meal snack delivery and/or extending their use to other time periods (i.e., regularly scheduled meals, evening snack periods).

Data Analysis

Because CNAs typically provide the majority of daily feeding assistance in the LTC setting, CNAs were used as a comparison group for the quality of feeding assistance care provided by newly trained non-nursing staff. Furthermore, prior studies of the feeding assistant training program implemented during regularly scheduled meals used CNAs as a comparison group for care quality (Bertrand et al., 2011; Simmons et al., 2007). Individual item and overall percentages were compared using Pearson chi-square to assess differences between groups using a statistical significance level of .05. Average total staff assistance time (recorded in minutes and seconds) and caloric intake were compared using t tests to assess the difference between trained staff and CNAs for the same residents. All analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 23.

Results

Staff Training

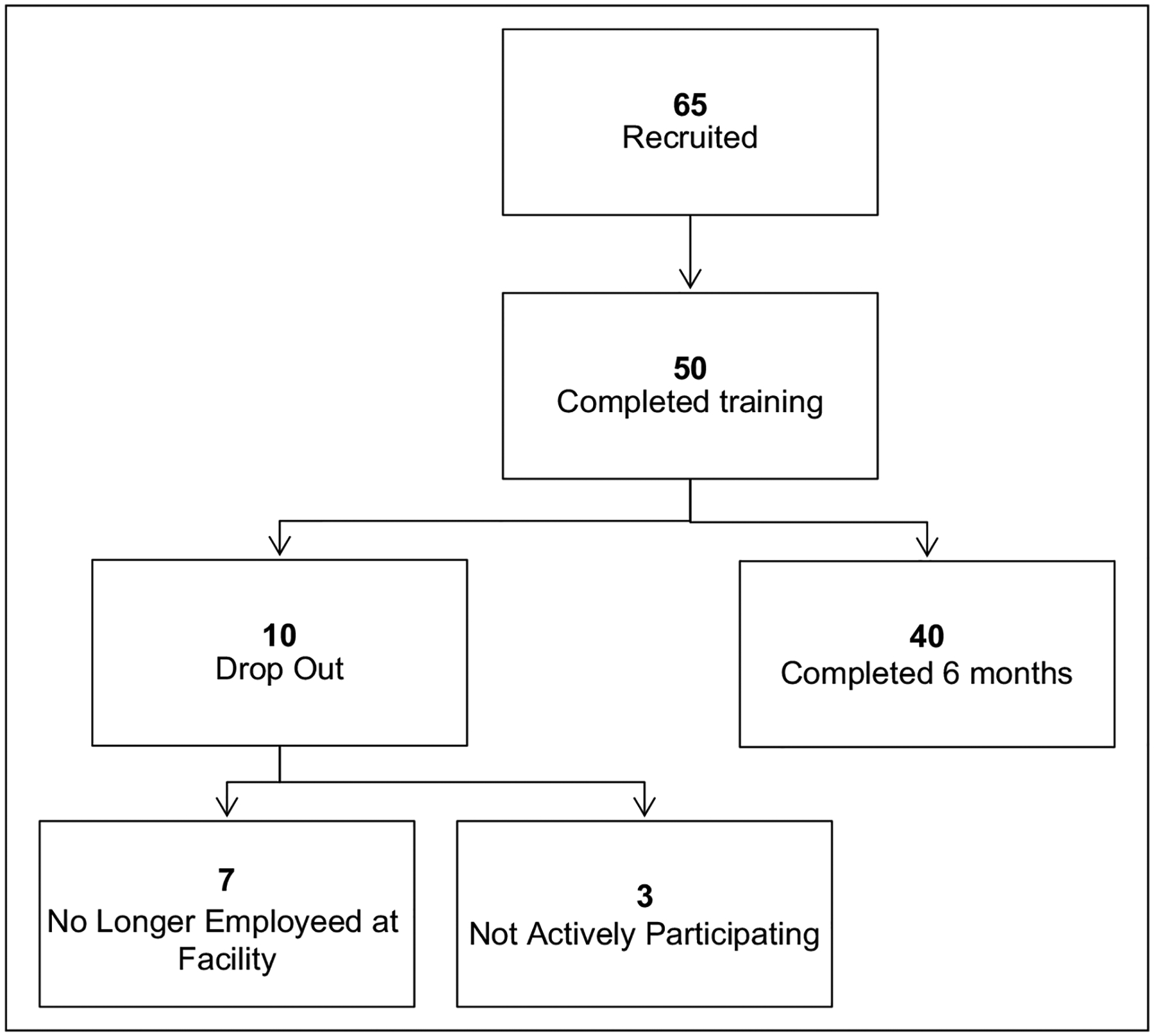

Three community volunteers and 47 non-nursing staff members from multiple departments completed the training across the five LTC sites. Housekeeping, upper level management and/or administrative personnel, nutrition service personnel, and social activities personnel were the most common types of staff to participate in training (Table 1). The majority of trained staff (74.4%, n = 29) were full-time, day shift staff who had been employed by the facility for more than 2 years prior to training (Table 1). Of the 50 staff who completed training, 40 (80%) provided routine assistance with between-meal care throughout the 24 study weeks. Of the remaining 10 trained staff, seven were no longer employed by the facility after 24 weeks (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Trained Feeding Assistant Characteristics Across Five Participating Facilities.

| Trainees (n = 50) % (n) | |

|---|---|

| Original department | |

| Housekeeping | 30 (15) |

| Upper level management/administrative staff | 24 (12) |

| Nutrition services | 20 (10) |

| Social activities | 10 (5) |

| Volunteers | 6 (3) |

| Maintenance | 4 (2) |

| Nursing supervisors | 4 (2) |

| Rehabilitation therapists | 2 (1) |

| Participation | |

| Mandatory | 62 (31) |

| Voluntary | 38 (19) |

| Length of employment | |

| Less than 6 months | 2.6 (1) |

| 6–12 months | 7.7 (3) |

| 1–2 years | 15.4 (6) |

| More than 2 years | 74.4 (29) |

Figure 1.

Staff recruitment and completion of training across 6 months.

Standardized Observations of Trained Staff and CNAs During Care Provision

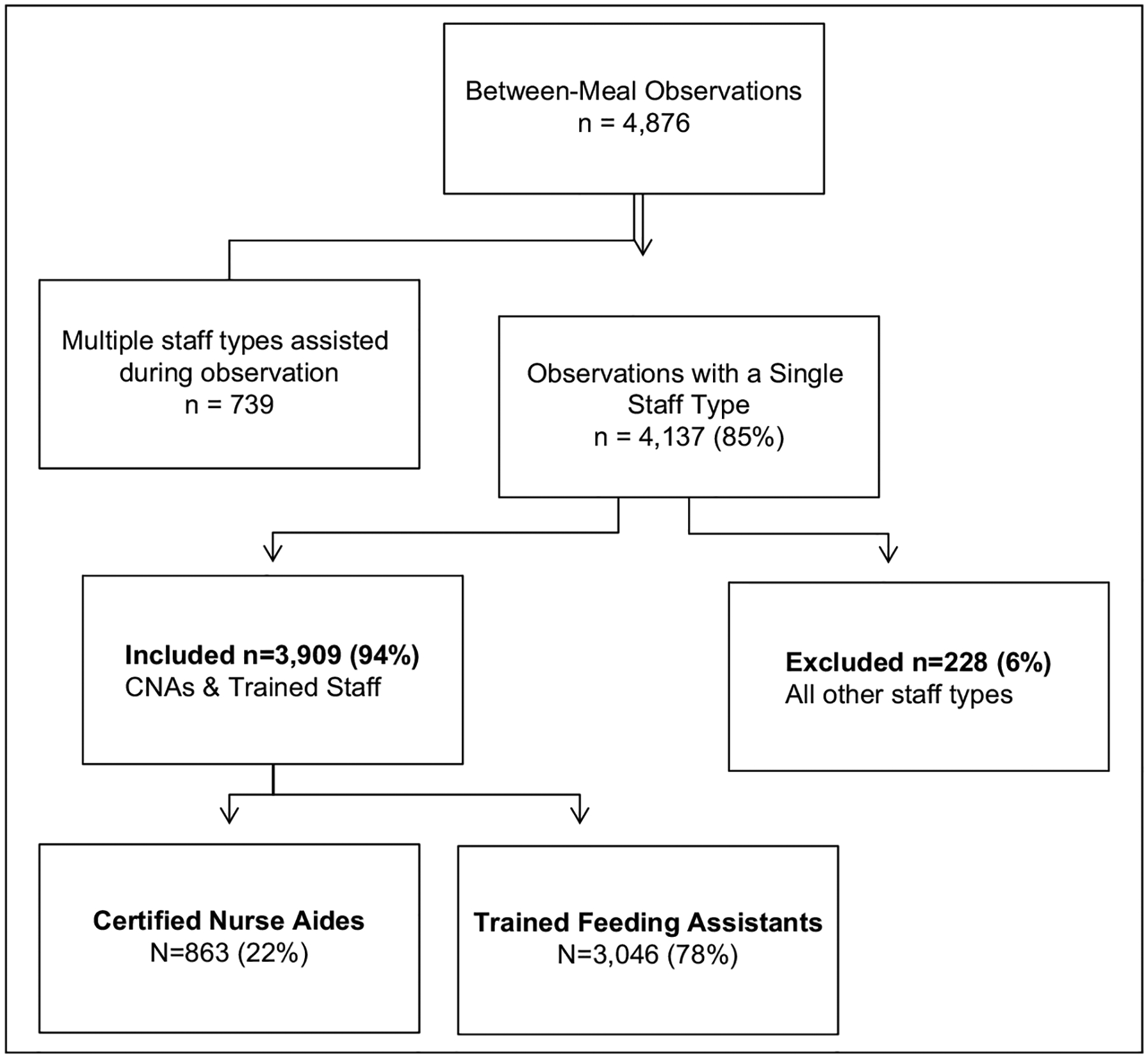

As shown in Figure 2, research staff completed 4,876 between-meal observations (M = 79.9 observations per resident of a possible total of 96 per resident) across all study weeks. A total of 739 observations were excluded from data analysis due to multiple types of staff providing assistance during the same observation period for the same resident (e.g., CNA and licensed nurse). Of the remaining 4,137 observations, 3,909 (94%) represented observations during which between-meal assistance was provided exclusively by either trained staff (3,046 or 78%) or CNAs (863 or 22%); thus, these 3,909 observations were the focus of the comparison analyses (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Between-meal observations for analyses.

Based on these 3,909 observations, both trained staff and CNA performance for the 13 between-meal care process measures are shown in Table 2. Results showed that trained staff performed significantly better than their CNA counterparts for 12 of these 13 measures. For example, trained staff offered residents a choice more often for both beverages (42% vs. 5%) and foods (60% vs. 10%) relative to CNAs (Table 2). Trained staff also provided better quality assistance as defined by social stimulation (85% vs. 63%), verbal cueing (91% vs. 77%), and seating themselves across from the resident (71% vs. 50%) during between-meal care episodes to encourage caloric intake (Table 2).

Although possible to achieve an average percentage of 100% for all items (Simmons et al., 2015), neither staff type averaged a “perfect score” even though trained staff were required to achieve 100% across all items as part of their initial performance evaluation. For example, the care process measures that showed the lowest performance among trained staff, albeit still significantly better than CNAs, included offering an alternative when resident intake was low (Table 2; 13% vs. 5%) and offering a second serving, when appropriate (Table 2; 14% vs. 4%). Across all observations, trained staff averaged a completion rate of 67.8% (±18.87%) across the 13 care process measures, which was significantly higher than the 44.7% (±16.59%) averaged by CNAs (t = 32.74, p < .001). Across all observations, trained staff also spent significantly more time with residents per care episode (2.57 ± 3.32 min) compared with CNAs (1.77 ± 2.40 min; t = 6.63, p < .000). Although both groups had a low average assistance time, there still was a significantly higher proportion of between-meal episodes during which trained staff spent more than 5 min (or until resident finished their served items) providing assistance to promote consumption relative to CNAs (41% vs. 32%). The higher quality care and assistance time provided by trained staff translated into higher between-meal caloric intake for residents. Specifically, the same residents consumed, on average, significantly more calories per snack offer from trained staff (130 ± 126 kcal) compared with snack offers from CNAs (77 ± 94 kcal; t = 11.63, p < .001).

Staff Interviews

Trained staff (n = 39) and CNA (n = 73) interview data from the final month of intervention are presented to gauge overall perception of the training program and implementation. Trained staff reported that they helped a median of 3.3 residents per day, with 66.7% reporting that their resident assignment changed daily or weekly. Despite the varying resident assignment, 87.2% of trainees responded “yes” to the following question: “Do you feel comfortable with your resident assignment and their feeding assistance needs?” All trainees who completed the interview (100%) also reported that they helped with at least one other nutritional care task, with the three most common being delivering meal trays during regularly scheduled mealtimes (93.3%), taking residents to and from the dining room for meals (87.2%), and retrieving alternatives from the kitchen when a resident does not like the served meal (86.2%). Furthermore, 80.0% of initially trained staff continued to provide feeding assistance care to residents after 6 months (Figure 1).

Most (84.9%) CNAs who completed an interview reported that they had 2 or more years of experience working as a CNA, but only 17.8% (n = 13) reported that they had received special training on feeding assistance outside of their CNA certification training. Overall, 94.5% of the CNAs responded “yes” to the following question: “Do you think it is helpful to have trained staff assist with nutritional care tasks?” When asked the follow-up, open-ended question, “What do they do that is helpful to you?” CNAs reported that it allowed them to assist more residents in a timely manner and spend more time with individual residents who needed extra help. When asked, “Do you have any concerns about the use of trained staff to provide feeding assistance?” only nine of 73 CNAs (12.3%) reported any concerns, with the majority of concerns related to potential choking risks for some residents (n = 5), ensuring knowledge of residents’ prescribed diet orders (n = 2), and the general comfort level of trained staff in providing feeding assistance (n = 2).

Following 6 months of intervention, research staff attempted to interview each facility’s upper level staff members who were either directly involved in the training program and/or played a key role in program implementation. A total of 11 interviews were completed across the five facilities with facility administrators (n = 3), staff developers (n = 3), directors of nursing (n = 2), and registered dietitians (n = 3). Across all upper level staff, none expressed concerns with the use of trained staff for feeding assistance care. However, multiple upper level staff acknowledged the practical implementation challenges of recruiting staff for training (n = 2), creating a consistent schedule for trained staff to provide assistance (n = 2), and coordinating the schedules of trained staff with nursing staff (n = 1). Overall, all upper level staff reported a positive impact of the training program for residents’ between-meal nutritional care. Specifically, upper level staff described the stabilization of residents’ body weights (n = 9) and increased socialization between residents and staff (n = 7) as two of the most noticeable impacts when asked the following open-ended question: “What, if any, is the impact [of the program] on residents?” Moreover, upper level staff also commented that trained staff had a positive impact on nursing staff (both CNAs and licensed nurses) by easing their care burden (n = 4), and they viewed trained staffs’ provision of quality feeding assistance care as a good reminder for nursing staff on how to interact with residents to encourage intake (n = 3). In this context, they noted that CNAs likely would benefit from receiving the same training as a refresher to their prior CNA certification training. Overall, 100% of the upper level staff (n = 11) in each facility reported that they planned to continue to utilize trained staff to assist with mealtime and/or between-meal tasks. Finally, four of the five facilities had a state survey during the 6 months of program implementation, and none received survey deficiencies or citations (i.e., F-tags) related to their use of trained staff, and in fact, two staff developers reported positive feedback from state surveyors about the program.

Discussion

The consistent delivery of quality feeding assistance care continues to be a challenge in many LTC facilities due to a majority of residents in need of staff assistance and the amount of staff time required for this daily care task (CMS, HHS, 2015a; Simmons & Schnelle, 2006b). The results of this study suggest that, with proper training and oversight, the use of non-nursing personnel to assist with feeding assistance during and/or between regularly scheduled meals provides a feasible way for facilities to augment their existing, often limited, nurse aide staffing for this daily care task. However, few facilities nationwide report having utilized this training program, per the federal regulation, to improve care quality (Division of Health Policy Management, School of Public Health, University of Minnesota, 2012).

Although the primary concern previously posed by nursing homes has been the quality of care provided by trainees and the potential for survey violations (Kapp, 2013; Remsburg, 2004; Simmons et al., 2007), the results of this and one prior study have now shown that trained staff provide feeding assistance care that is comparable with and, in most cases better than, the care provided by their CNA counterparts within the same facilities. In fact, trained staff in this study performed significantly better than CNAs on 12 of 13 individual between-meal care process measures as well as an overall measure of quality, and these measures are consistent with regulatory guidelines for optimal care quality. In addition, all levels of staff, including CNAs and upper level management personnel, reported positive program benefits and few to no concerns beyond the feasibility of on-going recruitment and scheduling of trained staff. In addition, trained staff reported being comfortable in their new job role.

Despite upper level staff concerns about the feasibility of continued program implementation (Bertrand et al., 2011; Simmons et al., 2007), 80% of the trained staff in this study were still routinely helping with nutritional care tasks 6 months after training. Thus, the initial 8 hr of training proved to be a worthwhile investment in these facilities, and upper level staff in all five sites reported that they intended to continue and/or expand their training program after the study. The continuation of the trained feeding assistant program at these five LTC facilities poses new challenges and opportunities. During the study, research personnel served as the primary “champions” of the program and provided most of the organization and supervision of the trained staff. Thus, upper level management will need to assume more responsibility for daily program implementation in the absence of research personnel support. However, engagement of upper level staff also could facilitate greater investment in the program at all levels of staff. Neither trained staff nor CNAs achieved “perfect scores” on the care process measures. In fact, it is notable that multiple upper level staff commented during their interviews that CNAs could benefit equally from additional training specific to feeding assistance care quality, even though they had received at least some training in this area as part of their CNA certification. Thus, upper level staff in a supervisory role should continue to intermittently observe both mealtime and between-meal care using the appendix as a guide for on-going management and continuous quality improvement.

There are a few notable limitations of this study. First, this study included only five community LTC facilities located in one geographic region. It is noteworthy that the five participating sites each had average nurse aide staffing levels that fell below the national average, which suggests that these facilities likely were in need of additional help with daily feeding assistance care. Second, this study targeted long-stay residents who were at risk for poor nutritional status; thus, study results may be specific to this subset of the nursing home population. Third, this study was conducted as part of a larger intervention study such that the comparisons between trained staff and CNAs were for a relatively small group of residents randomized to the intervention group, although this small sample yielded a large number of observations across all study weeks. Also, research staff were not blind to type of staff (CNAs vs. trained staff) when conducting observations; however, the use of a standardized form was intended to limit the potential for bias. Finally, there were other types of staff who assisted both during and between meals (e.g., licensed nurses) as well as family members or other visitors. However, assistance provided by these other groups occurred too infrequently to make valid comparisons between trained staff and multiple other types of staff. Still, their intermittent assistance suggests that an “all hands on deck” philosophy to nutritional care may be the best approach within a given facility, wherein all available staff across all levels are trained to help during peak care periods.

In summary, both between-meal and mealtime care tasks are typically provided by CNAs, who are often understaffed and also have a high turnover rate (Bostick et al., 2006; Crogan & Shultz, 2000; Temple et al., 2009). Thus, training non-nursing staff provides a practical way to improve feeding assistance care quality within the constraints of existing staffing resources, particularly for facilities with nurse aide staffing below the national average. Improving feeding assistance care quality is especially important because it is required by a significant proportion of residents for whom inadequate dietary intake can lead to multiple poor health outcomes (Agarwal et al., 2013; Blaum et al., 1995; Ferguson et al., 1993; Thomas et al., 2013). A comprehensive training program that meets federal and state requirements and consistently utilizes multiple trained staff to assist both during and between meals may serve a crucial role in mediating these risks.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by the National Institute of Aging (NIA) R01 grant 1R01AG033828-01A2 awarded to Sandra F. Simmons (Principal Investigator) and registered as a clinical trial (NCT02567526). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agency. The authors thank the nursing home facilities, residents and their families for allowing us to work closely with them as part of this project.

Biographies

Emily K. Hollingsworth, MSW, is a research coordinator at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Center for Quality Aging, and served as the coordinator for the larger NIA R01 study.

Emily A. Long, BA, BS, is a research associate (RA) at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Center for Quality Aging, and served as an RA on the NIA R01 study. More information can be found about the Center for Quality Aging mission, personnel and related projects at www.VanderbiltCQA.org.

Sandra F. Simmons, PhD, is an associate professor of medicine in the Division of Geriatrics at Vanderbilt University. Her appointments include staff member at the Vanderbilt Center for Quality Aging and the Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center (GRECC), Veterans Administration.

Appendix

| DID THE STAFF MEMBER | YES | NO | NA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Wash hands or use hand sanitizer before serving the next resident | |||

| 2. | Greet the resident by name? | |||

| 3. | Introduce self and/or orient resident to the snack? | |||

| 4. | Offer the resident a choice of at least two fluids (may or may not include supplements)? | |||

| 5. | Offer the resident a choice of foods (list choices to include a variety of snack foods)? | |||

| 6. | Ensure that the resident is sitting upright, to the greatest extent possible? (If repositioning not needed, NA) | |||

| 7. | Seat themselves either beside or across from the resident (if providing full physical assistance)? | |||

| 8. | Social interaction among staff/residents present at any point during the snack period? | |||

| 9. | Provide verbal instruction or orientation (includes prompts to eat for residents who eat independently and, if physically dependent, letting the resident know what food or fluid is being offered)? | |||

| 10. | Offer alternative food/fluid items if the resident is eating less than half of the initial snack choice or complains about the initially served items? | |||

| 11. | Offer the resident a second serving, if 100% of first serving is consumed or the resident requests more of either food(s) or fluid(s)? | |||

| 12. | Provide small, manageable bites/drinks for the resident, if providing full physical assistance to eat? | |||

| 13. | Spend at least 5 min providing assistance or until resident finished? (If in a group setting, give credit if staff stays in the area/room) | |||

| Percent Pass Rate: (No. of “yes”)/(No. of “yes” + No. of “no”) | ||||

Note. Observer Instructions: One form per observation. Indicate “YES” or “NO” by marking an “X” in the appropriate column in response to each item. Some items might be “Not Applicable” (NA) for individual residents or snack periods (e.g., Items 2 and 13).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Agarwal E, Ferguson M, & Banks M (2013). Malnutrition and poor food intake are associated with prolonged hospital stay, frequent readmissions, and greater in-hospital mortality: Results from the Nutrition Care Day Survey 2010. Clinical Nutrition, 32, 737–745. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2012.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand R, Porchak T, Moore TJ, Hurd DT, Shier V, Sweetland R, & Simmons SF (2011). The nursing home dining assistant program a demonstration project. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 23(2), 34–43. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20100730-04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaum CS, Fries BE, & Fiatarone MA (1995). Factors associated with low body mass index and weight loss in nursing home residents. The Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 50A(3), M162–M168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostick JE, Rantz MJ, Flesner MK, & Riggs CJ (2006). Systematic review of studies of staffing and quality in nursing homes. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 7, 366–376. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2006.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castle NG, & Engberg J (2005). Staff turnover and quality of care in nursing homes. Medical Care, 43, 616–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Department of Health and Human Services (2003). Medicare and Medicaid programs; requirements for paid feeding assistants in long term care facilities: Final rule. Federal Register, 68, 55528–55539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Department of Health and Human Services (2015a). Minimum Data Set 3.0 Public Records. Retrieved from https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Computer-Data-and-Systems/Minimum-Data-Set-3-0-Public-Reports/Minimum-Data-Set-3-0-Frequency-Report.html

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Department of Health and Human Services (2015b). Nursing home compare—The official U.S. government site for Medicare. Retrieved from https://www.medicare.gov/nursinghomecompare/search.html

- Crogan NL, & Shultz JA (2000). Nursing assistants’ perceptions of barriers to nutrition care for residents in long-term care facilities. Journal for Nurses in Staff Development, 16, 216–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Division of Health Policy Management, School of Public Health, University of Minnesota. (2012). NH regulations plus. Retrieved from http://www.hpm.umn.edu/nhregsplus/NHRegsbyTopic/TopicDietaryServices.html#descriptionfed

- Ferguson RP, O’Connor P, & Crabtree B (1993). Serum albumin and prealbumin as predictors of clinical outcomes of hospitalized elderly nursing home residents. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 41, 545–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapp MB (2013). Nursing home culture change: Legal apprehensions and opportunities. The Gerontologist, 53, 718–726. doi: 10.1093/geront/gns131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayser-Jones J, & Schell E (1997). The effect of staffing on the quality of care at mealtime. Nursing Outlook, 45, 64–72. doi: 10.1016/S0029-6554(97)90081-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson DR (2008). Memorandum report: Trends in nursing home deficiencies and complaints, OEI-02-08-00140. Washington, DC. Retrieved from https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-08-00140.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Remsburg RE (2004). Pros and cons of using paid feeding assistants in nursing homes. Geriatric Nursing, 25, 176–177. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2004.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnelle JF, Cretin S, Saliba D, & Simmons SF (2000). Minimum nurse aide staffing required to implement best practice care in nursing homes. In Report to Congress: Appropriateness of minimum nurse staffing ratios in nursing homes (pp. 14.1–14.68). Cambridge, MA: Abt Associates Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Schnelle JF, Simmons SF, Harrington C, Cadogan M, Garcia E, & Bates-Jensen M (2004). Relationship of nursing home staffing to quality of care. Health Services Research, 39, 225–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00225.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons SF (2007). Quality improvement for feeding assistance care in nursing homes. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 8(Suppl. 3), S12–S17. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2006.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons SF, Bertrand R, Shier V, Sweetland R, Moore TJ, Hurd DT, & Schnelle JF (2007). A preliminary evaluation of the paid feeding assistant regulation: Impact on feeding assistance care process quality in nursing homes. The Gerontologist, 47, 184–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons SF, Hollingsworth E, Long E, Liu X, Shotwell M, Keeler E, … Silver H (2017). Training non-nursing staff to assist with nutritional care delivery in nursing homes: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 65, 313–322. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons SF, Keeler E, An R, Liu X, Shotwell MS, Kuertz B, … Schnelle JF (2015). Cost-effectiveness of nutrition intervention in long-term care. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 63, 2308–2316. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons SF, Keeler E, Zhuo X, Hickey KA, Sato H, & Schnelle JF (2008). Prevention of unintentional weight loss in nursing home residents: A controlled trial of feeding assistance. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 56, 1466–1473. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01801.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons SF, Osterweil D, & Schnelle JF (2001). Improving food intake in nursing home residents with feeding assistance: A staffing analysis. The Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 56A(12), M790–M794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons SF, & Patel AV (2006). Nursing home staff delivery of oral liquid nutritional supplements to residents at risk for unintentional weight loss. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 54, 1372–1376. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00688.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons SF, & Reuben D (2000). Nutritional intake monitoring for nursing home residents: A comparison of staff documentation, direct observation, and photography methods. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 48, 209–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons SF, & Schnelle JF (2004). Individualized feeding assistance care for nursing home residents: Staffing requirements to implement two interventions. The Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 59, M966–M973. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.9.M966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons SF, & Schnelle JF (2006a). A continuous quality improvement pilot study: Impact on nutritional care quality. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 7, 480–485. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2006.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons SF, & Schnelle JF (2006b). Feeding assistance needs of long-stay nursing home residents and staff time to provide care. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 54, 919–924. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00812.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple A, Dobbs D, & Andel R (2009). Exploring correlates of turnover among nursing assistants in the National Nursing Home Survey. Health Care Management Review, 34, 182–190. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e318221c34b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J, Cooney L, & Fried T (2013). Systematic review: Health-related characteristics of elderly hospitalized adults and nursing home residents. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 61, 902–911. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]