Abstract

Background

Several school‐based interventions are effective in improving child diet and physical activity, and preventing excessive weight gain, and tobacco or harmful alcohol use. However, schools are frequently unsuccessful in implementing such evidence‐based interventions.

Objectives

1. To evaluate the benefits and harms of strategies aiming to improve school implementation of interventions to address student diet, physical activity, tobacco or alcohol use, and obesity.

2. To evaluate the benefits and harms of strategies to improve intervention implementation on measures of student diet, physical activity, obesity, tobacco use or alcohol use; describe their cost or cost‐effectiveness; and any harms of strategies on schools, school staff or students.

Search methods

We used standard, extensive Cochrane search methods. The latest search was between 1 September 2016 and 30 April 2021 to identify any relevant trials published since the last published review.

Selection criteria

We defined 'Implementation' as the use of strategies to adopt and integrate evidence‐based health interventions and to change practice patterns within specific settings. We included any trial (randomised controlled trial (RCT) or non‐randomised controlled trial (non‐RCT)) conducted at any scale, with a parallel control group that compared a strategy to implement policies or practices to address diet, physical activity, overweight or obesity, tobacco or alcohol use by students to 'no intervention', 'usual' practice or a different implementation strategy.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard Cochrane methods. Given the large number of outcomes reported, we selected and included the effects of a single outcome measure for each trial for the primary (implementation) and secondary (student health behaviour and obesity) outcomes using a decision hierarchy. Where possible, we calculated standardised mean differences (SMDs) to account for variable outcome measures with 95% confidence intervals (CI). For RCTs, we conducted meta‐analyses of primary and secondary outcomes using a random‐effects model, or in instances where there were between two and five studies, a fixed‐effect model. The synthesis of the effects for non‐randomised studies followed the 'Synthesis without meta‐analysis' (SWiM) guidelines.

Main results

We included an additional 11 trials in this update bringing the total number of included studies in the review to 38. Of these, 22 were conducted in the USA. Twenty‐six studies used RCT designs. Seventeen trials tested strategies to implement healthy eating, 12 physical activity and six a combination of risk factors. Just one trial sought to increase the implementation of interventions to delay initiation or reduce the consumption of alcohol. All trials used multiple implementation strategies, the most common being educational materials, educational outreach and educational meetings.

The overall certainty of evidence was low and ranged from very low to moderate for secondary review outcomes.

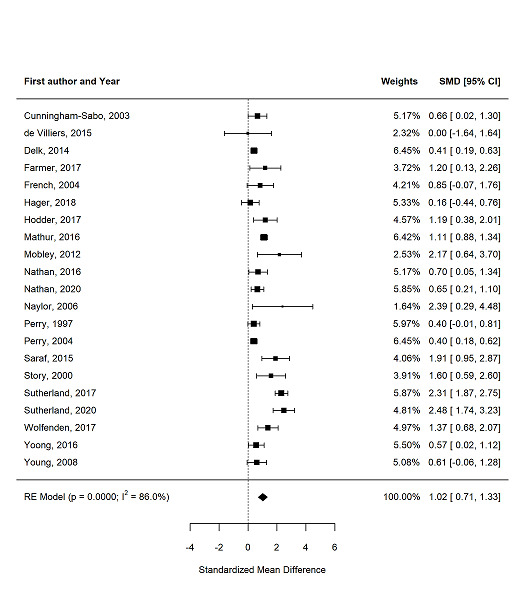

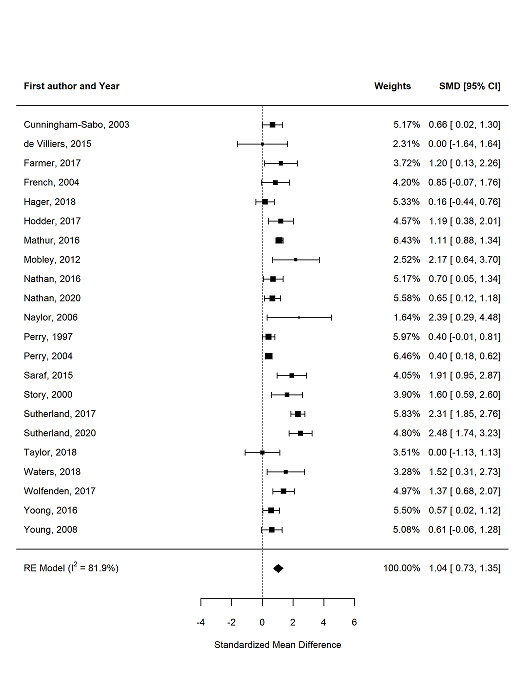

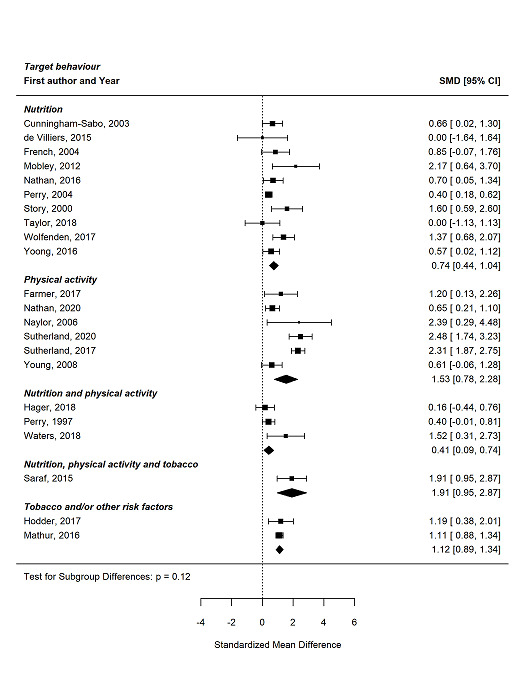

Pooled analyses of RCTs found, relative to a control, the use of implementation strategies may result in a large increase in the implementation of interventions in schools (SMD 1.04, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.34; 22 RCTs, 1917 participants; low‐certainty evidence). For secondary outcomes we found, relative to control, the use of implementation strategies to support intervention implementation may result in a slight improvement on measures of student diet (SMD 0.08, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.15; 11 RCTs, 16,649 participants; low‐certainty evidence) and physical activity (SMD 0.09, 95% CI −0.02 to 0.19; 9 RCTs, 16,389 participants; low‐certainty evidence). The effects on obesity probably suggest little to no difference (SMD −0.02, 95% CI −0.05 to 0.02; 8 RCTs, 18,618 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence). The effects on tobacco use are very uncertain (SMD −0.03, 95% CIs −0.23 to 0.18; 3 RCTs, 3635 participants; very low‐certainty evidence). One RCT assessed measures of student alcohol use and found strategies to support implementation may result in a slight increase in use (odds ratio 1.10, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.56; P = 0.60; 2105 participants). Few trials reported the economic evaluations of implementation strategies, the methods of which were heterogeneous and evidence graded as very uncertain. A lack of consistent terminology describing implementation strategies was an important limitation of the review.

Authors' conclusions

The use of implementation strategies may result in large increases in implementation of interventions, and slight improvements in measures of student diet, and physical activity. Further research is required to assess the impact of implementation strategies on such behavioural‐ and obesity‐related outcomes, including on measures of alcohol use, where the findings of one trial suggest it may slightly increase student risk. Given the low certainty of the available evidence for most measures further research is required to guide efforts to facilitate the translation of evidence into practice in this setting.

Keywords: Child, Humans, Diet, Exercise, Nicotiana, Obesity, Obesity/prevention & control, Policy, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Tobacco Use

Plain language summary

Improving the implementation of school‐based policies and practices to improve student health

Key messages

• Schools and their staff implement interventions to address student healthy eating, physical activity, obesity, and tobacco or alcohol use better when strategies are used to support them to do so. • School‐based interventions whose implementation is supported may be slightly more effective in improving student healthy eating, physical activity, obesity or tobacco use. • Most studies do not report economic evaluation of strategies to support implementation of interventions in schools or assess any potential adverse effects.

What did we want to find out?

We wanted to find out how effective strategies were in supporting the implementation of school‐based interventions to address student diet, physical activity, unhealthy weight gain, and tobacco or alcohol use. We wanted to know if they were cost‐effective and if they had any adverse effects. Examples of strategies include methods of improving quality, education and training, feedback on how the school was doing, prompts and reminders, and educational resources (e.g. manuals).

What did we do?

We updated a previous search we had conducted for studies that compared the use of a strategy to support intervention implementation to those that had not, or that had compared two or more different implementation strategies. The studies had looked at strategies to support the implementation of interventions in schools that addressed student nutrition, physical activity, obesity, or tobacco or alcohol use. We compared and summarised the results and rated our confidence in the evidence, based on factors such as study methods and sizes.

What did we find?

We found 11 new trials to add to those identified in our previous search, bringing the total number of included studies to 38. Most were conducted in the USA and examined strategies to implement healthy eating or physical activity interventions. We found, compared with a control, the use of implementation strategies may result in large improvements in the implementation of interventions in schools, and slight improvements in student healthy eating and physical activity. There was probably little to no effect on student obesity. The effects of implementation strategies on tobacco use are very uncertain. Few trials assessed any economic benefits of the use of intervention implementation support strategies or any potential adverse effects for schools, staff or students.

What were the limitations of the evidence?

Despite our review showing that the use of implementation strategies resulted in large improvements in programme implementation, the studies used methods likely to introduce errors in their results and inconsistencies across included studies, and were primarily conducted in one country (USA). As a result, we have low confidence in the impact strategies to support implementation have on improving the implementation of intervention in schools and most of secondary outcomes (downgraded for risk of bias and variation in methods and results).

How up to date is this evidence?

We searched databases between 1 September 2016 and 30 April 2021.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Comparison of strategies for enhancing the implementation of school‐based policies or practices targeting risk factors for chronic disease.

| Outcome | Anticipated absolute effects | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence | What happens | |

| Risk with control | Risk with experimental | |||||

| Implementation of policies, practices or programmes that promote student health in schools | Mean PA practices achieved 0.5 (SD 0.7)a | SMD of 1.04 is equivalent to an increase in the implementation of 0.73 of a school chronic disease prevention policy or practice | SMD 1.04 SD higher (0.74 higher to 1.34 higher) | 897 schoolsb (22 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊖⊖ Lowc | Implementation strategies may result in a large increase in the implementation of interventions in schools. |

| Student diet | Dietary diversity score (range 0–9) mean 4.54 (SD 1.22)d | SMD of 0.08 is equivalent to an improvement in dietary diversity score of 0.10 units | SMD 0.08 SD higher (0.02 higher to 0.15 higher) | 16,649 participants (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ Lowe | Implementation strategies may result in slight improvements in student nutrition outcomes. |

| Student physical activity | Mean steps/day 2556.85 (SD 557.27)f | SMD of 0.09 is equivalent to an improvement of 50 steps/day more | SMD 0.09 SD higher (0.02 lower to 0.19 higher) | 16,389 participants (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ Lowg | Implementation strategies may result in slight improvements in student physical activity outcomes. |

| Student obesity | Mean BMI 19.1 (SD 3.7)h | SMD of −0.02 is equivalent to a reduction of BMI by 0.074 points |

SMD 0.02 SD lower (0.05 lower to 0.02 higher) | 18,618 participants (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ Moderatei | Implementation strategies probably result in little to no difference in measures of student obesity. |

| Student tobacco use | See comments | See comments | SMD 0.03 SD lower (0.23 lower to 0.18 higher) | 3635 participants (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊖⊖⊖ Very lowj | We are very uncertain about the effect of implementation strategies on tobacco use outcomes. |

| Adverse events | See comment | See comment | — | (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ Lowk | Interventions had little to no impact of on adverse events. |

| Cost‐effectiveness | See comment | See comment | — | (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊖⊖⊖ Very lowl | We are uncertain whether strategies to improve the implementation of school‐based policies, practices or programmes targeting risk factors for chronic disease are cost‐effective. |

| BMI: body mass index; PA: physical activity; RCT: randomised controlled trial; SD: standard deviation; SMD: standardised mean difference. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aBaseline estimates and SDs used from Sutherland 2020. bNumber of school reported rather than participants as implementation data were not reported at the participant level and may have included school, class, individual or some other level data. cDowngraded one level for unclear/high risk of bias and one level for substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 81%; 50% to 90% considered substantial heterogeneity). cBaseline estimates and SD used from de Villiers 2015. dDowngraded one level for unclear/high risk of bias and one level for substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 63%; 50% to 90% considered substantial heterogeneity). eBaseline estimates and SD used from Nathan 2020. fDowngraded one level for substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 83%; 50% to 90% considered substantial heterogeneity) and one level for imprecision as 95% CI included both benefits and harms. gBaseline estimates and SD used from Naylor 2006. hDowngraded one level for imprecision as 95% CI included both benefits and harms. iDowngraded one level for unclear/high risk of bias, one level for substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 81%; 50% to 90% considered high heterogeneity), and one level for imprecision as 95% CI include both benefits and harms. jDowngraded one level for unclear/high risk of bias and one level for small number of studies reporting adverse outcomes. kDowngraded one level for unclear/high risk of bias, one level for indirectness given the small number of studies providing assessment on cost‐effectiveness, and one level for imprecision given the small number of schools in total.

Background

Description of the condition

Five health risks (i.e. poor diet, physical inactivity, tobacco smoking, risky alcohol consumption and obesity) are the most common modifiable causes of chronic disease (Murray 2020). These risk factors, all among the top 20 risk factors contributing to global death and disability, each account for a significant proportion of the total global disease burden: dietary risks (14.1%), physical inactivity (1.4%), tobacco smoking (7.9%), alcohol misuse (4.3%) and high body‐mass index (BMI) (8.9%) (Institute for Health 2020). Together, they were responsible for more than 650 million years lived with disability and 26 million deaths in 2019 (Institute for Health 2020). As a consequence, reducing the impact of these modifiable health risks in the community has been identified as a public health priority, and this has not changed since the early 2010s (WHO 2011; WHO 2021).

Targeting health risks in children is an important chronic disease prevention strategy, as health behaviours established in childhood are likely to track into adulthood (Cruz 2018; Hayes 2019). Schools are an attractive setting for the implementation of child‐focused chronic disease‐prevention interventions as they offer continuous and intensive contact with children for prolonged periods (WHO 2017). Furthermore, evidence from systematic reviews support a range of benefits from school‐based health interventions (Brown 2019; Foxcroft 2011; Hodder 2017; Jacob 2021; Liu 2019; Thomas 2013). For instance, classroom based physical activity interventions are effective in increasing children's physical activity as well as other health and education outcomes (Martin 2017). Systematic reviews, including one Cochrane Review, found school‐based prevention interventions of one year or more in duration were effective in reducing smoking rates by up to 12% (Thomas 2013). Similarly, previous Cochrane Reviews have reported examples of effective school‐based obesity and alcohol prevention interventions (Brown 2019; Foxcroft 2011). Finally, systematic review evidence also suggests, when implemented, school food policy interventions are generally effective in improving the food environment and dietary intake of school students (Micha 2018). Given such evidence, international chronic disease prevention strategies recommend the implementation of effective interventions targeting student diet, physical activity, tobacco and alcohol use and excessive weight gain (Ministry of Health 2011; WHO 2012; Australian Health Minister' Advisory Council 2017; Gassner 2022). Currently, the implementation of evidence‐based chronic disease‐prevention interventions in schools is suboptimal. Research conducted in the USA, Canada and Australia, for example, suggests that less than 10% of schools are compliant with legislation, policy or nutrition guidelines regarding the sale and promotion of healthy foods in schools (Chriqui 2013; De Silva‐Sanigorski 2011; Downs 2012; Vine 2021). In Australia, one report highlighted that 24% of schools did not provide students with 150 minutes of structured physical activity each week (Nathan 2020), as recommended by the sector (NSW Government 2021). In one national survey in Japan, just 14.3% of municipalities had implemented a smoke‐free policy in all elementary and junior high schools (Kayaba 2005), while studies in India reported a minority of schools implement policies prohibiting the use of tobacco by staff inside school buildings (Pradhan 2021).

Description of the intervention

Effective school‐based interventions to reduce chronic disease risks cannot improve population health outcomes if school systems and staff do not implement them (Eccles 2009; MacDonald 2016). However, the process of translating research into practice is complex. As a conceptual guide, the US National Institutes of Health described five phases of the translation (T) process (T0 to T4) from research discovery to population health impact (Glasgow 2012; Khoury 2010). Earlier phases (T0 to T2) focus on basic science, epidemiology and testing the efficacy of health interventions. T3 is dedicated to research designed to increase the implementation of evidence‐based interventions (also referred to as practices, policies or programmes) in practice (Glasgow 2012). This is achieved through 'implementation strategies' — techniques designed to change practice patterns within specific settings to improve the 'implementation' of evidence‐based health interventions (Glasgow 2012; Rabin 2008). There are several implementation strategies that have the potential to improve the likelihood of schools' implementation of interventions (e.g. policies and practices) to promote student health and reduce the risk of future disease including those listed in the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) taxonomy (EPOC 2015). Such strategies include continuous quality improvement processes, educational materials, performance monitoring, local consensus processes and educational outreach visits. To build the evidence regarding the impact of these strategies on measures of intervention implementation, the conduct of implementation trials has been recommended (Wolfenden 2021).

How the intervention might work

Schools are complex environments in which health interventions may be implemented (Kremser 2011). A range of factors, operating at multiple levels, may influence the success of implementation efforts (Darlington 2018). The mechanisms by which implementation strategies facilitate implementation of interventions in this setting are under‐researched and not well understood (Darlington 2018; Lee 2018). Theories and frameworks, such as Normalisation Process Theory or the Theoretical Domains Framework, can be applied to gain insight as to how such strategies can be used to support the implementation of a school‐based chronic disease prevention interventions (Cane 2012; May 2018; Rapley 2018). Similarly, comprehensive implementation frameworks describe a number of factors within schools, and external to them, that can influence the success of implementation including: characteristics of the intervention, individuals (i.e. knowledge skills, attitudes), the organisation (i.e. organisational culture) and the broader environmental contexts (Damschroder 2009), such as system‐wide policies. Similarly, systematic reviews of diet (Ronto 2020), physical activity (Cassar 2019; Nathan 2018), and substance use (Waller 2017) interventions in schools have identified a range of barriers or facilitators impacting their implementation including, the prevailing political or funding environment, school readiness to change, school priorities, the support of key school constituents (e.g. parent and teachers) and staff knowledge, skill, time and resources. The selection of implementation strategies should be based on those known (have evidence of) or believed (theoretically) to be able to overcome barriers to implementation within a given context (Department of Health 2018).

Why it is important to do this review

Studying the effectiveness of implementation strategies provides important information to guide future implementation research. Such evidence is also important to inform the decisions of policymakers and practitioners responsible for ensuring evidence‐based chronic disease prevention interventions are sufficiently implemented to yield health benefits. A number of systematic reviews have been conducted describing the effectiveness of strategies to implement practice guidelines and improve professional practice of clinicians in clinical settings, such as audit and feedback (Tuti 2017), reminders (Arditi 2017), education meetings (Forsetlund 2021), and incentives (Heider 2020). To our knowledge, few systematic reviews of implementation trials have been conducted assessing the impacts of implementation strategies in schools, including our 2017 Cochrane Review (Rabin 2010; Naylor 2015; Wolfenden 2017). These reviews concluded that evidence regarding the effectiveness of implementation strategies in this setting is uncertain. Given the policy relevance of such research, and as the literature searches of these reviews were undertaken several years ago, and a number of likely eligible studies have been published since, an update of our Cochrane Review is warranted. Specifically, this review aims to update our previous Cochrane Review (Wolfenden 2017), and provide evidence for how health promotion practitioners, education systems and other stakeholders can design and better implement interventions in the school setting to promote the health of students.

Objectives

1. To evaluate the benefits and harms of strategies aiming to improve school implementation of interventions to address student diet, physical activity, tobacco or alcohol use, and obesity.

2. To evaluate the benefits and harms of strategies to improve intervention implementation on measures of student diet, physical activity, obesity, tobacco use or alcohol use; describe their cost or cost‐effectiveness; and any harms of strategies on schools, school staff or students.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Strategies to improve the implementation of interventions are often complex and have been evaluated using a wide variety of methods and research designs. While results of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are considered more robust and are commonly used to assess the impact of implementation strategies (Brown 2017; Wolfenden 2016a), the use of randomised designs can be impractical or inappropriate for complex interventions (Glasgow 1999). As such, and to provide a more comprehensive assessment of the broader body of evidence, we included any trial (RCT or non‐RCT) with a parallel control group examining the effect of an implementation intervention published in any language. We included the following trial designs:

RCTs and cluster‐RCTs;

non‐RCTs and cluster non‐RCTs; and

controlled before‐after studies (CBAs), cluster‐CBAs.

Studies assessing any strategy aiming to improve the implementation of interventions in a school setting that targeted healthy eating, physical activity, tobacco or alcohol prevention, or obesity prevention (or combination of) were eligible. To be included, trials were required to report between‐group comparisons of the impact of a defined implementation strategy on an implementation outcome. Given the emergence of this literature, and as a limited number of new studies were anticipated, we did not apply an exclusion criteria based on a minimum number of clusters per group.

Types of participants

,We included studies set in schools (e.g. elementary, primary, secondary, middle, high and central schools) where the age of students was typically between five and 18 years. Study participants could be any stakeholders who may influence the uptake, implementation or sustainability of a target health‐promoting intervention (policy, practice or programme) in schools, including students, teachers, managers, cooks or other staff of schools and education departments. Study participants may also have included administrators, officials or representatives of school services, or other health, education, government or non‐government personnel responsible for encouraging or enforcing the implementation of health promoting interventions in this setting. We excluded studies or arms of trials assessing implementation performed by research staff.

Types of interventions

We included studies that tested implementation strategies designed to improve the implementation of interventions (policies, practices or programmes) targeting student diet, physical activity, prevention of tobacco or alcohol use, or obesity. Studies could compare the effects of implementation strategies with: 1. no active implementation strategy (inclusive of delayed implementation strategy, usual practice or minimal support); or 2. other implementation strategies. For trials that did not describe comparison conditions, but reported the findings against a comparison group, we assumed that the comparison was usual practice.

To be eligible for inclusion, studies had to include strategies to improve implementation by those involved in the usual delivery, uptake or use of interventions in schools (e.g. usual teaching staff). We defined implementation strategies as methods or techniques used to enhance the adoption, implementation and sustainability of an evidence‐based intervention (Proctor 2013). A number of taxonomies describing distinct implementation strategies exist (EPOC 2015; Powell 2015). In this review, we used the EPOC taxonomy to describe implementation strategies. Strategies could include quality improvement initiatives, education and training, performance feedback, prompts and reminders, implementation resources (e.g. manuals), financial incentives, penalties, communication and social marketing strategies, professional networking, use of opinion leaders, implementation consensus processes or other strategies consistent with the previous review. Strategies could be directed at individuals, classes, or whole schools or broader systems.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Implementation of policies, practices or programmes that promote student health in schools

The primary review outcome was a measure of school intervention implementation. Implementation measures were those that assessed the delivery (i.e. implementation) of an intervention by usual school personnel. It could include measures of the comprehensiveness, completeness or quality of implementation, for example, the mean number of curricula lessons taught or the proportion of schools implementing canteen services consistent with guidelines. Attitudes regarding implementation, such as measures of school or other stakeholder acceptability or feasibility were not considered measures of implementation. We included trials reporting only follow‐up data of an implementation outcome (i.e. no baseline data) if it used a randomised design as baseline values were assumed to have been equivalent, or if the baseline values could be assumed to be zero (e.g. the implementation of a curriculum not available at baseline).

Given the large number of potential implementation measures reported in trials, we selected and included the effects of a single trial outcome measure for each trial, consistent with previous reviews (Tang 2021). We developed a hierarchy for measure selection based on that employed by Tang and colleagues (Tang 2021). Specifically, we prioritised continuous (over dichotomous) measures of implementation outcomes; where multiple continuous outcomes were reported, we selected the outcomes considered most valid (e.g. objective measures were selected over self‐report measures); otherwise we randomly selected one of the continuous outcome measures using the RANDBETWEEN function in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation 2013). For trials reporting only dichotomous outcomes, and where there was sufficient information, we sought to re‐express effect sizes as continuous standardised outcomes. We selected the dichotomous outcome measure considered most valid; otherwise, we randomly selected a dichotomous outcome using the RANDBETWEEN function in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation 2013). This represented a change in approach from the previously published version of this review where we extracted all eligible measures of implementation and summarised their effects.

The included outcome measures may have been derived from data obtained from audits of school records, questionnaires or surveys of staff, direct observation or recordings, examination of routinely collected information from government departments (such as compliance with food standards or breaches of department regulations) or other sources.

Secondary outcomes

Diet

Physical activity

Obesity

Tobacco use

Adverse events

Costs

Data on secondary outcomes were only extracted for measures corresponding to the implementation outcomes reported in the included trials. For example, in a trial of an intervention targeting physical activity and healthy eating, but where an implementation strategy and implementation outcome data were only reported for healthy eating interventions, we extracted only data related to diet (e.g. foods or beverages consumed by students or student BMI, or both). Secondary outcomes included measures of the following student risk factors: poor diet, physical inactivity, tobacco or alcohol use, or obesity. If an intervention targeted multiple risk factors, we selected outcomes and extracted data for each risk factor addressed.

Similar to the selection of measures of the primary outcome, we did not include all eligible measures of secondary outcomes for all reported risk factors. Instead, we included a single outcome for each risk using a decision hierarchy following the guidance of Section 3.2.4.3 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (McKenzie 2022a; Tang 2021); where we prioritised continuous (over dichotomous) measures of implementation outcomes; and outcomes considered most valid. This new approach was different to the previous version of this review and required the re‐extraction and selection of outcomes for inclusion in this update. Specifically, we worked systematically through the hierarchy, in descending order starting at each level (and progressing each step) until we identified a measure of an eligible risk factor. Where we identified multiple measures at the same level and step, we randomly selected a single measure. The hierarchy for each risk factor is explained below.

Diet

-

Level 1: validated measures of student diet (e.g. food record, validated food frequency):

step 1: whole day estimates of diet including measures of the quantity or frequency of foods or nutrients consumed (e.g. total calories consumed; daily serves of fruit and vegetables, measure of macronutrient intake, or score‐based measures of diet quality); then

step 2: part day (e.g. during school hours) estimates of student diet.

-

Level 2: non‐validated measures of student diet (e.g. food record, validated food frequency):

step 1: whole day estimates of diet including measures of the quantity or frequency of foods or nutrients consumed (e.g. total calories consumed; daily serves of fruit and vegetables, measure of macronutrient intake, or score‐based measures of diet quality); then

step 2: part day (e.g. during school hours) estimates of student diet.

Within this hierarchy, for obesity prevention studies, or those undertaken in the context of an obesity prevention initiative (as defined by authors of the included studies), we gave preference to measures of energy intake over other dietary intake outcomes. For trials that were not undertaken in the context of an obesity prevention initiative, we gave preference to other measures of dietary intake. Also, where score‐based measures were used to assess diet or nutritional quality, the total questionnaire scores representing whole diet were included in preference to subgroup scores representing specific diet components (e.g. de Villiers 2015). Where summary estimates for questionnaires were split for healthy and unhealthy food groups, the healthy food estimates were included (Hoelscher 2010). As food purchased for consumption has been identified to represent a reliable estimate of food intake, we included food purchase data in this review; however, we gave preference to measures of actual consumptions when both were available (e.g. Taylor 2018).

Physical activity

-

Level 1: device‐measured physical activity (e.g. accelerometer, pedometer):

step 1: whole‐day estimates of physical activity;

step 2: part‐day (e.g. during school hours) estimates of physical activity;

step 3: measures of physical activity intensity (whole day then part day).

-

Level 2: self‐reported measures of physical activity:

step 1: whole‐day estimates of physical activity;

step 2: part‐day (e.g. during school hours) estimates of physical activity;

step 3: measures of physical activity intensity (whole day then part day).

Level 3: self‐report data of fitness was extracted.

Obesity

Level 1: objectively measured BMI, with BMI z‐scores preferred over non‐standardised BMI scores if available.

Level 2: other objective estimates of anthropometry (e.g. weight, waist circumference).

Level 3: self‐reported estimates of anthropometry (e.g. self‐reported weight).

Tobacco use

Level 1: validated self‐reported measures of tobacco use (e.g. current tobacco use).

Level 2: non‐validated self‐reported measures of smoking rates.

Level 3: other estimates of tobacco use (e.g. cigarette butt counts).

'Current use' measures were preference for inclusion over 'ever use' measures.

Alcohol use

Level 1: validated self‐reported measures of alcohol use (e.g. 24‐hour recall, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test).

Level 2: non‐validated self‐reported measures of alcohol use.

Current or daily use, or measures of drinking at harmful levels (e.g. binge‐drinking) were preferences over 'ever use' measures.

Cost and adverse events

The following data on cost and adverse events were also extracted.

All estimates of absolute costs, relative or incremental costs, or any assessment of the cost‐effectiveness of strategies to improve implementation of policies, programmes or practices in schools; and

Any reported unintended adverse consequences of a strategy to improve implementation of policies, programmes or practices in schools; these could include adverse impacts on child health (e.g. unintended changes in other risk factors, injury), school operation or staff attitudes (e.g. impacts on staff motivation or cohesion following implementation), or the displacement of other key programmes, curricula or practice.

Search methods for identification of studies

We performed a comprehensive search for both published and unpublished research studies across a broad range of information sources to reflect the cross‐disciplinary nature of the topic. Articles published in any language were eligible and there were no restrictions regarding article publication dates.

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases between 1 September 2016 and 30 April 2021 to identify any relevant trials published since the last published review (Wolfenden 2017):

the Cochrane Library including the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

MEDLINE (Ovid);

MEDLINE In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations (Ovid);

Embase Classic and Embase (Ovid);

PsycINFO (Ovid);

Education Resource Information Center (ERIC; Proquest);

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL; Ebsco);

Dissertations and Theses (Proquest); and

SCOPUS (SCOPUS).

We adapted the MEDLINE search strategy for each database using database‐specific subject headings, where available (Appendix 1). We included filters used in other systematic reviews for research design (Waters 2011), population (Guerra 2014), physical activity and healthy eating (Dobbins 2013; Guerra 2014; Jaime 2009), obesity (Waters 2011), tobacco use prevention (Thomas 2013), and alcohol misuse (Foxcroft 2011). A search filter for intervention (implementation strategies) was developed based on previous reviews (Wolfenden 2016), and common terms in implementation and dissemination research (Rabin 2008).

Searching other resources

We screened reference lists of all included trials for citations of potentially relevant studies and contacted authors of included studies for other potentially relevant trials. We handsearched all publications between 1 July 2011 and 30 April 2021 in the journals: Implementation Science and Journal of Translational Behavioral Medicine. We also conducted searches of the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (apps.who.int/trialsearch/), and the US National Institutes of Health registry (clinicaltrials.gov) from 30 August 2016 to 30 April 2021. We consulted with experts in the field to identify other relevant research. To identify companion papers of identified eligible trials, we also conducted Google Scholar searches of the first 100 citations identified by a search of the trial name or title.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

In this update, pairs of review authors (from SMc, CW, KN, KO, SY, FS and CB) independently screened titles and abstracts using Covidence (Covidence). We obtained full texts of all remaining potentially relevant or unclear articles and pairs of review authors (from SMc, NN, SY, RS, FT, FS, CB, KN and KO) independently reviewed these against our inclusion criteria. Studies identified as potentially eligible that were also authored by a member of the review team had their eligibility independently assessed by a review author who had no part in the conduct of the study to confirm eligibility. We used Google Translate for abstracts or had translation conducted by non‐English‐speaking collaborators. At each stage of the screening process, we resolved disagreements by discussion and consensus between the two review authors and, where required, by consulting a third review author (LW; arbitration was not required on any study LW was an author on). We recorded reasons for exclusion of studies at this stage in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Data extraction and management

Pairs of review authors (from SMc, CB, KN, KO) independently extracted data in duplicate using a piloted data extraction form. We resolved any disagreements in data extraction by discussion and consensus, or by consulting a third author (LW; arbitration was not required on any study LW was an author on), where required.

For all outcomes, where there were differences in published information between peer‐reviewed and grey literature for the same trial, we used data from peer‐reviewed publications. Where key data were missing from the study reports, we attempted to contact the authors to obtain missing information.

We extracted and reported the following study characteristics:

information regarding study eligibility, study design, date of publication, school type, country, participant/school demographic/socioeconomic characteristics, number of experimental conditions and information to allow assessment of risk of study bias;

information describing the characteristics of the implementation strategy, including the duration, intervention (policy, programme, practice), information to allow classification against the EPOC Group 'Taxonomy of Interventions', and data describing consistency of the execution of the strategy with a planned delivery protocol (EPOC 2015). Data extractors coded descriptions of implementation strategies using the EPOC taxonomy descriptors;

information on extracted trial outcomes, including the data collection method, validity of measures used, effect size, measures of outcome variability, costs and adverse outcomes; and

information on the source(s) of research funding and potential conflicts of interest.

Two review authors (SM, LW) independently extracted statistical data for primary outcomes, in consultation with statisticians (CL, EN). One author (SM) entered data into a statistical spreadsheet for analysis. All analyses were performed in R 4.0.5 (R Core Team 2021).

For secondary outcomes, two review authors independently extracted secondary outcome data (SMc, CB, KN and KO). One review author (KO) entered the data in to a spreadsheet for analysis and a second review author checked it (SM). Analyses on secondary outcomes were performed in Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2020).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We conducted risk of bias assessment on the selected implementation outcome and secondary outcomes of interest. For included trials, we used Cochrane's RoB 1 tool for assessing risk of bias, which includes assessments based on six domains (selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias and other sources of bias) (Higgins 2011). We also included additional criteria for cluster‐RCTs including 'recruitment to cluster', 'baseline imbalance', 'loss of clusters', 'incorrect analysis' and 'compatibility with individually randomised trials'. We included an additional criterion 'potential confounding' for the assessment of the risk of bias in non‐randomised trial designs. We assessed domains as having 'low', 'high', or 'unclear' risk of bias in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We intend to reassess and update risk of bias tools in future updates in line with Cochrane guidance given new developments in this area.

We assessed overall risk of bias by review outcome at the study level by categorising studies based on risk of bias assessments for each domain. Overall risk of bias by study was determined for the primary outcome as:

low risk if 50% or more of the domains were assessed at low risk of bias;

high risk of bias if 50% or more of the domains were at high risk of bias;

unclear risk of bias if 50% or more of the domains were low or unclear risk of bias.

Where there was an even number of domains, we made a more conservative (i.e. high over unclear, unclear over low) overall domain bias (Egan 2018; Heath 2002; Hoelscher 2010; Simons‐Morton 1988). Two review authors (CB, SMc) assessed risk of bias independently for each study. We resolved any disagreements by discussion and consensus or, if required, by involving an additional author (LW; arbitration was not required on any study LW was an author on).

Measures of treatment effect

Where we performed meta‐analyses, we expressed the intervention effect for both continuous and dichotomous outcomes as a standardised mean difference (SMD) with 95% confidence interval (CI). We used this approach given the difference in measures reported in the included studies and as we were primarily interested in whether the use of implementation strategies had an effect broadly on implementation, or risk behaviour‐ or weight‐related outcomes rather than any specific measures of these outcomes. We interpreted the magnitude of effect size using the benchmarks suggested by Cohen, considering an SMD of 0.2 a small effect, 0.5 a medium effect and 0.8 a large effect (Cohen 1988).

Unit of analysis issues

We examined clustered studies for unit of analysis errors and recorded these if they occurred in the risk of bias tables. For both the primary and secondary outcomes, where possible, we used the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) provided in the manuscripts. If this was not available, we attempted to contact authors to provide ICCs. Failing this, for the implementation outcomes, we calculated the trials' effective sample size using an ICC of 0.02 as this represented a conservative value based off similar trials (Delk 2014). For the secondary outcomes, we used an ICC of 0.06 for both nutrition and physical activity outcomes. These were based off the mean of ICCs for nutrition and physical activity reported in Naylor 2006 (physical activity) and Story 2000 (nutrition). We calculated the design effect using the formula provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Dealing with missing data

When outcomes, methods or results of the studies were missing or unclear, we contacted the corresponding authors of the published trial to supply the data. Any information provided was incorporated into the review as appropriate. Any evidence of potential selective reporting or incomplete reporting of trial data was documented in the risk of bias tables. Our analyses were conducted using the intention‐to‐treat principle.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical heterogeneity by narratively describing similarities and differences in the characteristics of the study designs, settings, populations, implementation strategies, comparison groups and outcome measures. We assessed statistical heterogeneity using the I2 statistic with findings summarised in a forest plot and considered the following I2 statistic categories, together with other methodological and clinical considerations in the interpretation of heterogeneity:

0% to 40% might not be important (low heterogeneity);

30% to 60% might represent moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90% might represent substantial heterogeneity and

75% to 100% might represent considerable heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We compared published reports with information in trial registers and protocols to assess selective reporting bias where such information was available. Where we suspected selective reporting bias (via assessment of risk of bias in included studies), we attempted to contact study authors and ask them to provide missing outcome data. We reported instances of potential reporting bias in the risk of bias summary.

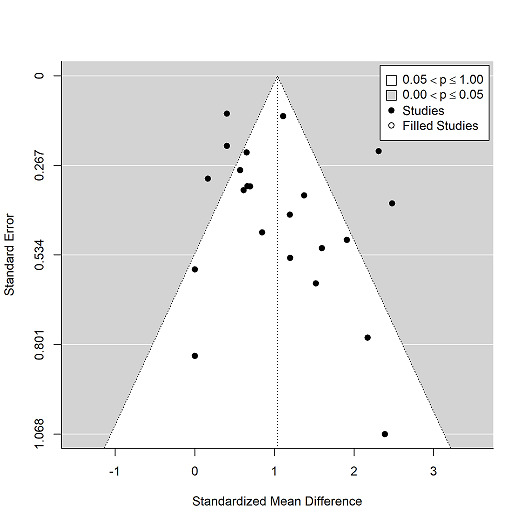

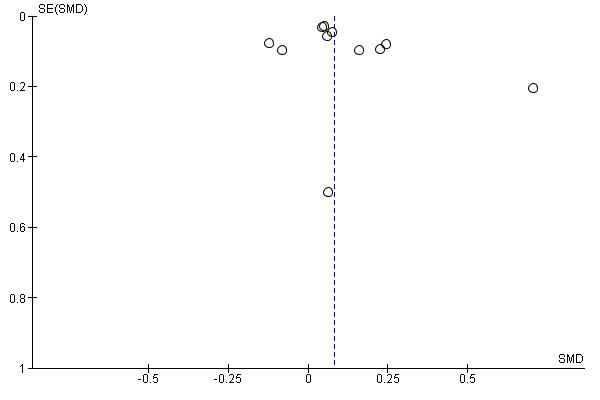

We used visual inspection of funnel plots to assess for publication bias. We used the trim and fill method to estimate the number of missing studies from funnel plots for the primary analysis (Duval 2000).

Data synthesis

We present the effects of interventions grouped first according to comparison (implementation strategy versus no active implementation strategy; implementation strategy versus alternate implementation strategy), second by trial design (RCTs and non‐RCTs) and finally by outcome.

For multi‐arm trials with a control group, we combined the active implementation strategy arms and compared it with the no active implementation strategy. We used the 'dmetar' package to pool multiple control or treatment arms (Harrer 2019). For multi‐arm trials with no control group ('no‐intervention' or usual care), we combined the 'more‐intensive' arms and compared it with the 'least‐intensive' implementation strategy arm. Where studies used multiple follow‐up periods, we used data from the final (most recent) study follow‐up.

For the study by Perry and colleagues the standard deviation (SD) in the control group was assumed to be equal to the SD in the treatment group and the two groups were assumed to have equal sample sizes (Perry 2004).

To describe the effects of implementation strategies reported in all included studies, for both non‐RCTs and RCTs, we reported the SMD of the primary review outcome. For continuous measures, we calculated an SMD using reported means and SDs. For dichotomous outcomes, we calculated the odds ratios (ORs) (from the raw n/N (%), i.e. number of events divided by the sample size) and transformed them to an SMD using the methods described in Anzures‐Cabrera and colleagues, where sufficient information was available in the published paper or on request from authors to do so (Anzures‐Cabrera 2011).

Randomised controlled trials

For the primary comparison, where the effects of implementation strategies were compared with a no active implementation strategy (e.g. no strategy or usual care) meta‐analysis was undertaken where possible. For both primary and secondary outcomes, we pooled data from RCTs in random‐effects meta‐analysis using the SMD (and 95% CIs). For primary trial outcomes, we calculated the SMD using the large‐sample approximation to compute sampling variances. We performed meta‐analyses using the 'metafor' package (Viechtbauer 2010). For secondary outcomes, we pooled data using generic inverse variance method using the Review Manager 5 software (Review Manager 2020). We used the random‐effects model in instances where data from five or more studies were available to pool, otherwise we used a fixed‐effect model. We selected postintervention follow‐up data over change‐from‐baseline data for inclusion in the meta‐analysis.

For three cluster‐RCTs, we selected the implementation measure (based on the hierarchy described above) for which clustering had not been accounted for by the original study (Nathan 2020; Sallis 1997; Sutherland 2017). For example, in Sutherland 2017, the implementation measure we selected was clustered at the teacher level; however, comparisons between groups were made using a t‐test.

Given the small number of RCTs reporting economic evaluations or measures of adverse effects, and their considerable heterogeneity, we presented the findings narratively. Similarly, and for the same reasons, we synthesised the findings of RCTs comparing two or more active implementation strategies narratively.

Non‐randomised studies

For the primary comparison, where the effects of implementation strategies were compared with a no active implementation strategy, we synthesised the findings of non‐RCTs based on guidance from the 'Synthesis without meta‐analysis' (SWiM) reporting guidelines (Campbell 2020; McKenzie 2022b). Specifically, for primary review outcomes, we described the findings across studies using vote counting based on the direction of effect (McKenzie 2022b) and reporting of the range of standardised effects and median. For comparisons of two or more active implementation strategies, and for analyses of all secondary outcomes (where standardised effects were not calculated), we summarised the effects of implementation strategies narratively, including the use of vote counting based on the direction of effect.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We undertook a preplanned subgroup analysis for studies in which implementation was attempted at scale – defined as 50 or more schools in the intervention group.

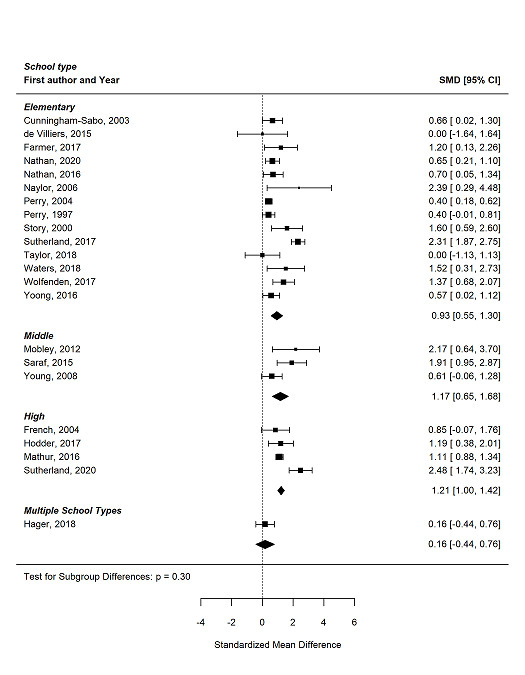

Additionally, we described the effects of implementation strategies by the following subgroups:

school type: that is, studies undertaken in elementary (students aged five to 12 years); middle (students aged 11 to 14 years) and high (students aged 12 to 18 years) school or those undertaken across school types (post hoc);

the health behaviour or risk factor targeted by the intervention (diet, physical activity, obesity, tobacco or alcohol) (post hoc).

These groupings were selected as they were considered of interest to public health policymakers and practitioners engaged in the production of the review, were exploratory, and were not prespecified. They were also considered the population and intervention characteristics that may most likely explain any observed heterogeneity. Using pooled data from RCTs, we undertook exploratory analyses to first test for subgroup differences (interaction), then describe the effects of implementation strategies by subgroups, and finally to describe any changes in observed statistical heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analysis

For pooled synthesis of the primary review implementation outcome we performed two sensitivity analyses. In the first, we removed studies from the meta‐analysis with an overall high risk of bias. In the second, we imputed ICC values of 0.01 and 0.05 for cluster‐RCTs that either did not account for clustering in the selected implementation measure and where study authors did not report ICC values.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We generated a summary of findings table to present the key findings of included studies for the main comparison intervention versus no active implementation strategy), based on recommendations of the Cochrane EPOC group and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Table 1; Higgins 2019). The summary of findings table included a list of primary outcome (implementation) in the review, a description of the intervention effect, the number of participants and studies addressing the outcome, and a GRADE assessment for the overall certainty of evidence for each outcome. We used data from RCTs only and for studies reporting the effects of interventions versus no active implementation strategy for the summary of findings table, as this was considered of primary interest to end‐users. We used GRADE to assess the certainty of the body of evidence through consideration of study limitations (inadequate sequence generation, lack of allocation concealment, lack of blinding participants/providers, lack of blinding outcome assessors, loss to follow‐up, selective outcome reporting and other bias), consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias. Two review authors (from SM, RH, KO) independently assessed the overall certainty of evidence using the GRADE system and consulted a third review author (LW) where consensus on any issues arising could not be reached. The certainty of the body of evidence for each individual outcome was graded accordingly as 'high', 'moderate', 'low' and 'very Low' in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; and Characteristics of ongoing studies tables.

Results of the search

The searches for the previous review (Wolfenden 2017), and this review update generated 31,156 citations (18,957 previous review; 12,199 this review update), after removal of duplicates. After screening the titles and abstracts, we removed 30,402 titles (18,572 previous review; 11,830 this review update) and reviewed the full texts of 754 records (385 previous review; 369 this review update). Of these, 11 new studies from 19 publications were identified for inclusion in this update, bringing the total number of studies included in this review to 38 (Figure 1). Additionally, we identified 17 ongoing studies (20 records) that are likely to meet the study inclusion criteria (see Characteristics of ongoing studies table).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Types of studies

Of the 38 included trials 22 were conducted in the USA (Alaimo 2015; Cheung 2018; Cunningham‐Sabo 2003; Delk 2014; Egan 2018; French 2004; Gingiss 2006; Hager 2018; Heath 2002; Hoelscher 2010; Lytle 2006; McCormick 1995; Mobley 2012; Perry 1997; Perry 2004; Sallis 1997; Saunders 2006; Simons‐Morton 1988; Story 2000; Taylor 2018; Whatley Blum 2007; Young 2008), with the remaining trials undertaken in India (Mathur 2016; Saraf 2015), Australia (Hodder 2017; Nathan 2012; Nathan 2016; Nathan 2020; Sutherland 2017; Sutherland 2020; Waters 2017; Wolfenden 2017; Yoong 2016), Canada (Bremer 2018; Naylor 2006), New Zealand (Farmer 2017), the Netherlands (Evenhuis 2020), and South Africa (de Villiers 2015).

In the assessment of implementation outcomes, eight studies employed RCT designs (Cunningham‐Sabo 2003; de Villiers 2015; Lytle 2006; Mobley 2012; Nathan 2016; Saunders 2006; Wolfenden 2017; Yoong 2016), 18 cluster‐RCT designs (Delk 2014; Farmer 2017; French 2004; Hager 2018; Hodder 2017; Mathur 2016; McCormick 1995; Nathan 2020; Naylor 2006; Perry 1997; Perry 2004; Saraf 2015; Story 2000; Sutherland 2017; Sutherland 2020; Taylor 2018; Waters 2017; Young 2008), and 12 non‐RCT designs (Alaimo 2015; Bremer 2018; Cheung 2018; Egan 2018; Evenhuis 2020; Gingiss 2006; Heath 2002; Hoelscher 2010; Nathan 2012; Sallis 1997; Simons‐Morton 1988; Whatley Blum 2007). Trial designs used to evaluate implementation outcomes differed at times from those used to assess secondary outcomes pertaining to student risk factors. For example, Saunders and colleagues assessed school level implementation outcomes (RCT design) as well as the impact of intervention implementation on individual student outcomes located within schools (cluster‐RCT) (Saunders 2006). There was variability in the types of participants, implementation strategies and outcomes reported.

Participants

Trials recruited samples of between two (Taylor 2018) and 723 (Nathan 2012) schools. In five trials, 50 or more schools were allocated to the intervention group to receive implementation support (Alaimo 2015; Cheung 2018; Gingiss 2006; Nathan 2012; Perry 1997). Most trials were conducted in elementary schools catering for children aged five to 12 years (Cheung 2018; Cunningham‐Sabo 2003; de Villiers 2015; Egan 2018; Farmer 2017; Heath 2002; Hoelscher 2010; Nathan 2012; Nathan 2016; Nathan 2020; Naylor 2006; Perry 1997; Perry 2004; Sallis 1997; Simons‐Morton 1988; Story 2000; Sutherland 2017; Taylor 2018; Waters 2017; Wolfenden 2017; Yoong 2016). Eight were conducted in middle schools where children are aged 11 to 14 years (Alaimo 2015; Delk 2014; Gingiss 2006; Lytle 2006; McCormick 1995; Mobley 2012; Saraf 2015; Young 2008), one in both elementary and middle schools (Bremer 2018), and seven in high schools only typically catering for children aged 12 or 13 years to 18 years of age (Evenhuis 2020; French 2004; Hodder 2017; Mathur 2016; Saunders 2006; Sutherland 2020; Whatley Blum 2007). Only one trial recruited from primary, middle and high schools (Hager 2018). Fourteen studies reported they were conducted in low‐income regions or in schools with students from predominantly low‐income households (Alaimo 2015; de Villiers 2015; Farmer 2017; Hager 2018; Heath 2002; Hodder 2017; Hoelscher 2010; Lytle 2006; Mathur 2016; Mobley 2012; Nathan 2012; Sutherland 2017; Sutherland 2020; Waters 2017).

Interventions

There was variability in the implementation strategies employed. All trials comprised of multiple discrete implementation strategies, the most common being: educational materials, educational outreach and educational meetings (Table 2). The EPOC taxonomy descriptors of the implementation strategies employed by included trials are described in (Table 3).

1. Interventions across studies.

| Trial | Audit and feedback | Clinical practice guidelines | Continuous quality improvements |

External funding |

Education games |

Education materials |

Education meeting |

Education outreach visits |

Inter‐ professional education |

Length of consultation |

Local consensus process |

Local opinion leader |

Managerial supervision | Monitoring performance of delivery | Pay for performance | Procurement and distribution of supplies | Tailored intervention |

The use of communication technology |

Other |

| Alaimo 2015 | — | X | — | X | — | X | — | X | — | — | X | — | — | — | — | — | X | — | — |

| Bremer 2018 | — | — | — | — | — | X | X | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | X |

| Cheung 2018 | — | — | — | — | — | X | X | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | X | — | — |

| Cunningham‐Sabo 2003 | — | X | — | — | — | X | X | X | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| de Villiers 2015 | — | — | — | — | — | X | X | X | — | — | — | X | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Delk 2014 | — | X | — | — | — | — | X | X | — | — | X | — | — | — | — | — | X | — | X |

| Egan 2018 | X | — | — | — | — | — | X | X | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | X | — | — |

| Evenhuis 2020 | X | — | — | — | — | X | — | X | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | X | — | — |

| Farmer 2017 | X | — | — | X | — | — | — | — | — | — | X | — | — | — | — | — | X | — | — |

| French 2004 | — | — | — | — | — | — | X | — | — | — | X | — | — | — | X | — | X | — | — |

| Gingiss 2006 | — | — | — | X | — | X | X | — | — | X | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| Hager 2018 | — | — | — | X | — | X | X | — | — | — | — | X | — | — | — | — | X | — | — |

| Heath 2002 | — | — | — | — | — | X | X | X | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Hodder 2017 | X | — | — | X | — | X | X | X | — | — | X | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Hoelscher 2010 | — | — | — | — | — | X | X | X | — | — | X | — | — | — | X | — | — | X | X |

| Lytle 2006 | — | — | — | — | — | X | X | — | — | — | X | X | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Mathur 2016 | — | — | X | — | — | X | X | — | — | — | X | X | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| McCormick 1995 | — | — | — | — | — | X | X | — | — | — | X | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Mobley 2012 | — | — | — | X | X | X | X | X | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | X | X | X |

| Nathan 2012 | — | — | — | — | — | X | X | — | — | — | X | X | — | X | — | — | X | — | X |

| Nathan 2016 | X | — | X | — | — | X | X | — | — | — | X | X | — | — | — | — | X | — | X |

| Nathan 2020 | — | — | — | — | — | X | — | X | — | — | — | X | — | — | — | — | X | — | X |

| Naylor 2006 | — | — | — | — | — | X | X | X | — | — | X | — | — | — | — | — | X | — | X |

| Perry 1997 | — | — | — | — | — | X | X | X | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | X |

| Perry 2004 | — | — | — | — | — | X | X | X | — | — | X | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | X |

| Sallis 1997 | — | — | — | — | X | X | X | — | X | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | X | |

| Saraf 2015 | — | — | — | — | X | X | X | — | — | — | X | X | — | — | — | — | X | — | X |

| Saunders 2006 | — | — | — | — | — | X | X | X | — | — | X | X | — | — | — | — | — | — | X |

| Simons‐Morton 1988 | — | — | — | — | — | X | — | X | — | — | X | X | X | X | — | — | — | — | X |

| Story 2000 | — | — | — | — | — | — | X | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | X |

| Sutherland 2017 | X | — | — | — | — | X | X | X | — | — | — | X | — | — | — | — | — | — | X |

| Sutherland 2020 | X | X | — | — | — | X | X | X | X | — | — | X | — | — | — | — | — | — | X |

| Taylor 2018 | — | — | — | X | — | X | — | X | — | — | X | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | X |

| Waters 2017 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | X | — | — |

| Whatley Blum 2007 | — | X | — | X | — | X | X | X | — | — | X | — | — | — | — | X | — | — | X |

| Wolfenden 2017 | X | — | X | X | — | X | X | X | — | — | X | X | — | — | — | — | X | — | X |

| Yoong 2016 | X | — | X | — | — | X | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | X | — | — |

| Young 2008 | — | — | — | — | — | X | X | X | X | — | X | X | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

2. Definition of Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) subcategories utilised in the review.

| EPOC subcategory | Definition |

| Audit and feedback | A summary of health workers’ performance over a specified period of time, given to them in a written, electronic or verbal format. The summary may include recommendations for clinical action. |

| Clinical practice guidelines | Clinical guidelines are systematically developed statements to assist healthcare providers and patients to decide on appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances'(US IOM). |

| Educational materials | Distribution to individuals, or groups, of educational materials to support clinical care, i.e. any intervention in which knowledge is distributed. For example this may be facilitated by the Internet, learning critical appraisal skills; skills for electronic retrieval of information, diagnostic formulation; question formulation. |

| Educational meetings | Courses, workshops, conferences or other educational meetings. |

| Educational outreach visits, or academic detailing | Personal visits by a trained person to health workers in their own settings, to provide information with the aim of changing practice. |

| External funding | Financial contributions such as donations, loans, etc. from public or private entities from outside the national or local health financing system. |

| Inter‐professional education | Continuing education for health professionals that involves > 1 profession in joint, interactive learning. |

| Length of consultation | Changes in the length of consultations. |

| Local consensus processes | Formal or informal local consensus processes, for example agreeing a clinical protocol to manage a patient group, adapting a guideline for a local health system or promoting the implementation of guidelines. |

| Local opinion leaders | The identification and use of identifiable local opinion leaders to promote good clinical practice. |

| Managerial supervision | Routine supervision visits by health staff. |

| Monitoring the performance of the delivery of healthcare | Monitoring of health services by individuals or healthcare organisations, for example by comparing with an external standard. |

| Other | Strategies were classified as other if they did not clearly fit within the standard subcategories. |

| Pay for performance – target payments | Transfer of money or material goods to healthcare providers conditional on taking a measurable action or achieving a predetermined performance target, for example incentives for lay health workers. |

| Procurement and distribution of supplies | Systems for procuring and distributing drugs or other supplies. |

| Tailored interventions | Interventions to change practice that are selected based on an assessment of barriers to change, for example through interviews or surveys. |

| The use of information and communication technology | Technology based methods to transfer healthcare information and support the delivery of care. |

Seventeen trials tested strategies to implement healthy eating policies, programmes or practices (Alaimo 2015; Cunningham‐Sabo 2003; de Villiers 2015; Evenhuis 2020; French 2004; Heath 2002; Lytle 2006; Mobley 2012; Nathan 2012; Nathan 2016; Perry 2004; Simons‐Morton 1988; Story 2000; Taylor 2018; Whatley Blum 2007; Wolfenden 2017; Yoong 2016), 12 tested strategies targeting physical activity policies or practices (Bremer 2018; Cheung 2018; Delk 2014; Egan 2018; Farmer 2017; Nathan 2020; Naylor 2006; Sallis 1997; Saunders 2006; Sutherland 2017; Sutherland 2020; Young 2008), and three targeted tobacco policies and practices (Gingiss 2006; Mathur 2016; McCormick 1995). Six trials targeted a combination of health behaviours, with four examining implementation of healthy eating and physical activity policies or practices (Hager 2018; Hoelscher 2010; Perry 1997; Waters 2017), and one trial examining policies or practices to improve implementation of tobacco control, healthy eating and physical activity initiatives (Saraf 2015). One trial examined tobacco and alcohol use (Hodder 2017).

Outcomes

Three trials collected implementation outcome (primary) follow‐up data up to six months postbaseline (Bremer 2018; Evenhuis 2020; Sutherland 2017), three trials at more than six to 11 months (Nathan 2020; Naylor 2006; Taylor 2018), one trial at 11 to 15 months (Nathan 2012) and 18 trials at 12 to 14 months (Cheung 2018; Delk 2014; Egan 2018; Farmer 2017; Hager 2018; Heath 2002; Hoelscher 2010; Mathur 2016; McCormick 1995; Nathan 2016; Saraf 2015; Saunders 2006; Simons‐Morton 1988; Story 2000; Sutherland 2020; Whatley Blum 2007; Wolfenden 2017; Yoong 2016). Another six trials collected follow‐up data at two years postbaseline (Alaimo 2015; Cunningham‐Sabo 2003; French 2004; Gingiss 2006; Perry 2004; Young 2008), one collected data at two and a half years (Sallis 1997), four trials at three years (de Villiers 2015; Hodder 2017; Lytle 2006; Perry 1997), and two at three and a half years (Mobley 2012; Waters 2017).

Eight trials used observation‐based measures to assess implementation outcomes (primary outcomes) (French 2004; Lytle 2006; Mathur 2016; Perry 2004; Sallis 1997; Story 2000; Sutherland 2017; Whatley Blum 2007). A further 10 trials used school records or documents (Cunningham‐Sabo 2003; Delk 2014; Evenhuis 2020; Heath 2002; Mobley 2012; Nathan 2016; Perry 1997; Taylor 2018; Wolfenden 2017; Yoong 2016). One school conducted chemical analysis (Simons‐Morton 1988), one school had researchers complete an implementation checklist (McCormick 1995), and one school conducted situational analysis (de Villiers 2015). Sixteen studies asked staff members (principals, teachers, canteen personnel, etc.) to complete surveys, interviews, checklists or activity logs (Alaimo 2015; Bremer 2018; Cheung 2018; Egan 2018; Farmer 2017; Gingiss 2006; Hager 2018; Hodder 2017; Nathan 2012; Nathan 2020; Naylor 2006; Saraf 2015; Saunders 2006; Sutherland 2020; Waters 2017; Young 2008). One study surveyed students on teacher‐led physical activity breaks (Hoelscher 2010).

Twelve trials assessed student physical activity (secondary outcome) at follow‐up (Bremer 2018; Farmer 2017; Hoelscher 2010; Nathan 2020; Naylor 2006; Perry 1997; Sallis 1997; Saraf 2015; Saunders 2006; Sutherland 2017; Waters 2017; Young 2008). Physical activity behaviours were assessed using accelerometer (Farmer 2017; Nathan 2020; Sutherland 2017; Young 2008), pedometer (Naylor 2006), participant recall (Saunders 2006), student or parent (or both) questionnaire (Bremer 2018; Saraf 2015; Waters 2017), observation (Hoelscher 2010; Perry 1997), and fitness‐tests (Sallis 1997). Seventeen trials assessed child nutritional intake or food selection, 13 using questionnaires (Alaimo 2015; Cunningham‐Sabo 2003; de Villiers 2015; Evenhuis 2020; French 2004; Hoelscher 2010; Lytle 2006; Mobley 2012; Saraf 2015; Simons‐Morton 1988; Story 2000; Waters 2017; Whatley Blum 2007), three using observation (Perry 2004; Taylor 2018; Wolfenden 2017). and one using menu and recipe data (Perry 1997). Eleven trials collected anthropometric measures, assessed objectively, from participants (Cunningham‐Sabo 2003; Farmer 2017; Heath 2002; Hoelscher 2010; Mobley 2012; Naylor 2006; Perry 1997; Sallis 1997; Saunders 2006; Waters 2017; Young 2008). Three trials assessed tobacco use, two using questionnaires (Hodder 2017; Saraf 2015) and one used observational data (Mathur 2016). One trial assessed student alcohol use via a questionnaire (Hodder 2017).

Three trials included a measure that was specified in the study methods as an assessment of potential unintended adverse effects (Mobley 2012; Taylor 2018; Wolfenden 2017), and three trials reported cost analyses (Heath 2002; Mobley 2012; Taylor 2018).

Types of comparisons

Of the 38 included studies, 29 compared the implementation strategy to no intervention, usual care/minimal support comparison group (Alaimo 2015; Bremer 2018; Cheung 2018; de Villiers 2015; Egan 2018; Evenhuis 2020; Farmer 2017; French 2004; Hager 2018; Hodder 2017; Lytle 2006; Mathur 2016; McCormick 1995; Mobley 2012; Nathan 2012; Nathan 2016; Nathan 2020; Naylor 2006; Perry 1997; Perry 2004; Sallis 1997; Saunders 2006; Sutherland 2017; Sutherland 2020; Taylor 2018; Waters 2017; Whatley Blum 2007; Wolfenden 2017; Yoong 2016). Two were comparative effectiveness studies (Delk 2014; Hoelscher 2010), and seven studies did not describe the comparison condition and so we assumed the comparison was usual practice (Cunningham‐Sabo 2003; Gingiss 2006; Heath 2002; Saraf 2015; Simons‐Morton 1988; Story 2000; Young 2008) (therefore, 36 studies included in the intervention versus non‐intervention, usual care/minimal support comparison).

Of the 36 studies that compared the implementation strategy to a control group, 33 compared to usual practice or waitlist control (usual practice: Alaimo 2015; Bremer 2018; Cheung 2018; Egan 2018; Evenhuis 2020; Farmer 2017; French 2004; Hager 2018; Hodder 2017; Lytle 2006; Mathur 2016; Mobley 2012; Nathan 2016; Nathan 2020; Naylor 2006; Perry 1997; Perry 2004; Sallis 1997; Saunders 2006; Sutherland 2017; Sutherland 2020; Taylor 2018; Waters 2017; Whatley Blum 2007; Wolfenden 2017; Yoong 2016; minimal support control (waitlist): de Villiers 2015; McCormick 1995; Nathan 2012). Of those comparing to minimal support, schools in Nathan 2012 received support (unspecified) from a non‐government agency to assist with implementation of a fruit and vegetable break if this was sought. In McCormick 1995, control schools received curricula in the post and technical assistance upon request. In de Villiers 2015, principals at schools in the control arm received a booklet with "tips" for healthy schools and a guide to resources that could be accessed to assist in creating a healthier school environment.

Thirty‐one of the studies that compared the implementation strategy to a control group were two arm trials (Bremer 2018; Cheung 2018; Cunningham‐Sabo 2003; de Villiers 2015; Evenhuis 2020; Farmer 2017; French 2004; Gingiss 2006; Heath 2002; Hodder 2017; Lytle 2006; Mathur 2016; McCormick 1995; Mobley 2012; Nathan 2012; Nathan 2016; Nathan 2020; Perry 2004; Sallis 1997; Saraf 2015; Saunders 2006; Simons‐Morton 1988; Story 2000; Sutherland 2017; Sutherland 2020; Taylor 2018; Waters 2017; Whatley Blum 2007; Wolfenden 2017; Yoong 2016; Young 2008), and five included more than two trial arms (Alaimo 2015; Egan 2018; Hager 2018; Naylor 2006; Perry 1997).

In the Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health (CATCH) trial, schools were randomly assigned to either an experimental condition or a control condition (Perry 1997). Of the 56 schools assigned to intervention, 28 schools were randomly assigned to an experimental arm targeting the same implementation outcomes and including the same implementation strategies, but were also asked to implement programmes targeting families. Implementation data for the two intervention groups were combined in the reporting of the paper and the combined data used in this review. The Sports, Play, and Active Recreation for Kids (SPARK) trial randomised schools to two active strategies and one control condition (Sallis 1997). Data were only extracted for two of the three assigned groups; the control group where implementation support was not provided and an experimental group where implementation support was provided to usual teaching staff to implement the intervention. The third group, where physical activity practices were implemented by external specialist physical education teachers hired by the research team was excluded as per review inclusion criteria. Of the two studies that were comparative effectiveness trials, Hoelscher 2010 had four comparison groups which were split into two categories; high and low implementers. The low implementers included a control group and an intervention group which only received one strategy. The high implementers contained two groups, one which received two and the other which received three implementation strategies. Delk 2014 had three comparison groups included, one which received the basic training only intervention (Basic), one which received the basic training only intervention plus facilitator support (Basic Plus), and a third which received the basic training only intervention plus facilitator support and a social marketing campaign (Basic Plus SM).

Excluded studies

We considered 330 papers to be ineligible. Primary reasons for exclusion included inappropriate: outcome (204 papers); study design (71 papers); intervention (17 papers); duplicates (15 papers); comparator (13 papers); setting (eight papers) and population (two papers). Studies were excluded based on 'inappropriate outcomes' if they: did not report any implementation outcomes; did not report implementation outcomes for both intervention and control groups; or did not report between‐group differences in implementation outcomes. In the Characteristics of excluded studies table, we reported a subset of key excluded studies. A full list of excluded studies is available on request.

Risk of bias in included studies

Assessment of risk of bias considered study design and reporting characteristics relevant to the implementation outcomes of the included studies (Figure 2; Figure 3). Risk of bias assessments for secondary outcomes are available in the Characteristics of included studies table.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

All 12 non‐RCTs had a high risk of selection bias for both random sequence generation and concealment of allocation (Alaimo 2015; Bremer 2018; Cheung 2018; Egan 2018; Evenhuis 2020; Gingiss 2006; Heath 2002; Hoelscher 2010; Nathan 2012; Sallis 1997; Simons‐Morton 1988; Whatley Blum 2007). For the 18 trials with cluster‐RCT designs, seven were considered low risk for random sequence generation (Farmer 2017; Hodder 2017; Nathan 2020; Saraf 2015; Sutherland 2017; Sutherland 2020; Waters 2017). Four of the eight trials using RCT designs were considered low risk for random sequence generation (de Villiers 2015; Nathan 2016; Wolfenden 2017; Yoong 2016). The remaining 15 trials were at unclear risk of selection bias (Cunningham‐Sabo 2003; Delk 2014; French 2004; Hager 2018; Lytle 2006; Mathur 2016; McCormick 1995; Mobley 2012; Naylor 2006; Perry 1997; Perry 2004; Saunders 2006; Story 2000; Taylor 2018; Young 2008). The bias for concealment was unclear for nine RCTs (Cunningham‐Sabo 2003; de Villiers 2015; Hager 2018; Lytle 2006; Mobley 2012; Nathan 2016; Saunders 2006; Wolfenden 2017; Yoong 2016). One RCT was at high risk of concealment bias (Taylor 2018). One cluster‐RCT was at risk of bias (Farmer 2017). Three cluster were at low risk of concealment bias (Nathan 2020; Sutherland 2020; Waters 2017). The remaining 12 cluster‐RCTs were at unclear risk of concealment bias (Delk 2014; French 2004; Hodder 2017; Mathur 2016; McCormick 1995; Naylor 2006; Perry 1997; Perry 2004; Sallis 1997; Story 2000; Sutherland 2017; Young 2008).

Blinding

All studies were considered to have high risk of performance bias, due to participants and research personnel not being blind to group allocation.