Abstract

The replication region of the lactococcal plasmid pCI2000 was subcloned and analyzed. The nucleotide sequence of one 5.6-kb EcoRI fragment which was capable of supporting replication when cloned on a replication probe vector revealed the presence of seven putative open reading frames (ORFs). One ORF exhibited significant homology to several replication proteins from plasmids considered to replicate via a theta mode. Deletion analysis showed that this ORF, designated repA, is indeed required for replication. The results also suggest that the origin of replication is located outside repA. Upstream and divergently transcribed from repA, an ORF that showed significant (48 to 64%) homology to a number of proteins that are required for faithful segregation of chromosomal or plasmid DNA of gram-negative bacteria was identified. Gene interruption and transcomplementation experiments showed that this ORF, designated parA, is required for stable inheritance of pCI2000 and is active in trans. This is the first example of such a partitioning mechanism for plasmids in gram-positive bacteria.

Lactococcus lactis strains are of considerable industrial and economic importance, as they are widely used in the production of a variety of fermented dairy products. A characteristic of Lactococcus strains is that they typically possess an abundance of plasmid DNA on which a number of significant technological traits are encoded. These include bacteriophage resistance, bacteriocin production, lactose assimilation, citrate utilization, and proteinase activity (11). Therefore, an extensive knowledge of lactococcal plasmid replication, partition, and stability functions is essential in order to ensure the stable maintenance of these traits. This information can also be applied for the generation of novel stable food-grade cloning and expression vectors for the manipulation of these hosts.

There are two modes of bacterial plasmid replication, rolling circle (RC) and theta (θ), both of which have been identified in Lactococcus. The RC plasmids are classified on the basis of homologies within the region of the double-stranded origin and the gene encoding the replication initiation protein. Two classes of RC plasmid are evident in Lactococcus, pE194-like and pC194-like, of which pWV01 (26, 28) and pWC1 (33), respectively, are the prototypes. In general, θ replicons are classified according to their structural organization and the requirement for host-encoded proteins in the replication process. Originally, the best-characterized θ replicating plasmids were of gram-negative origin, and three classes designated A, B, and C were identified. Class A plasmids possess an origin of replication (ori), which consists of an AT-rich region, adjacent to a number of iterons which are essential in cis for replication initiation. This mode of replication requires a plasmid-encoded replication initiation protein (Rep) and is DNA polymerase I independent. Class B and C replicons do not harbor a typical ori sequence and require host-encoded DNA polymerase I for replication. Class B plasmids differ from class C in that they do not encode a Rep protein.

An increasing number of θ replicating plasmids have been identified in gram-positive bacteria. The best characterized of these are pAMβ1 (6), pIP501 (5), and pSM19035 (5), which are structurally similar to class A plasmids but require DNA polymerase I in order to replicate; therefore, these have been categorized as class D (6). All these mechanisms are addressed in more detail in an extensive review of bacterial plasmid replication by del Solar et al. (10).

Recently, a new family of gram-positive θ replicons has been identified, of which pLS32 of Bacillus natto is the best studied (40). This plasmid does not possess an AT-rich region that could function as a putative origin of replication preceding the gene encoding the replication initiation protein (repN) (40). Within the coding sequence of RepN, however, several iterons that function as the origin of replication have been identified. Therefore, this replication region is structurally dissimilar to those of class A but has been shown to be DNA polymerase I independent (40). This family, based on structural organization and homology at the nucleotide and amino acid levels, includes a number of other plasmids of diverse origin, such as the previously unclassified Lactobacillus plasmids pLJ1 (39), pSAK1 (unpublished; accession no. gb: Z50862), and pLH1 (unpublished; accession no. emb: AJ222725); the staphylococcal plasmids pSX267 (18) and pSK41 (14); and the enterococcal plasmids pAD1 (22, 46), pCF10 (23), and pPD1 (15).

Low-copy-number plasmids usually encode additional functions to counteract plasmid loss at cell division. These include plasmid multimer resolution systems, plasmid-free killer systems, and active partition mechanisms (31, 47). In general, the active partition mechanisms require one or two plasmid-encoded trans-acting partition proteins and a cis-acting centromeric site at which one or possibly both proteins act. In the best-characterized systems, including those of P1, P7, and F, partition requires two gene products and one cis-acting site (1, 29, 47). In P1, the centromeric site has been identified as parS, which is a cis-acting 84-nucleotide (nt) DNA sequence containing a 13-bp inverted repeat that is required for accurate segregation of the newly replicated plasmids into daughter cells. parS is located downstream of the parAB locus which encodes two trans-acting proteins, ParA and ParB, both of which are essential for partition (19). In the mechanism exhibited by the Agrobacterium plasmid pTAR, only one partition protein, ParA, and one cis-acting site located upstream, in addition to the 3′ 125-nt region located downstream from parA, are necessary for stable inheritance of the plasmid (16).

To date, the replication regions of more than 20 lactococcal plasmids have been sequenced and have been shown to belong to the highly homologous pCI305-type family (21), of which pWV02 has been shown to replicate via the θ mode (27). On the basis of homologies and structural organization, these plasmids can be considered class A plasmids. Southern hybridization experiments have revealed that many lactococcal plasmids belong to this family (37, 38). A number of plasmids, however, contain replicons which do not show homology to the replication region of the pCI305 family. One such plasmid from L. lactis NCDO 275, designated pCI2000, was analyzed in more detail. Here we report the cloning and molecular analysis of its replication region. It was found to encode a novel lactococcal replicon, belonging to the pLS32 family. In addition, divergently transcribed from rep, a gene that showed homology to several partitioning proteins of gram-negative bacteria was found. This gene is required for stable plasmid inheritance and acts in trans. To our knowledge, these data provide the first proof of an active partition mechanism for plasmids of gram-positive bacteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, media, and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used are described in Table 1. Escherichia coli strains were cultured in Luria-Bertani broth as described by Sambrook et al. (36). The M17 medium of Terzaghi and Sandine (41) supplemented with 0.5% glucose (GM17) or 0.5% lactose (LM17) was used for subculturing L. lactis strains. The M17 medium made from first principles without β-glycerophosphate and supplemented with 0.5% glucose (GM17−) was utilized for the curing of plasmids from L. lactis NCDO 275. Chloramphenicol and erythromycin were used at final concentrations of 10 and 5 μg ml−1, respectively, for L. lactis. Ampicillin, kanamycin, chloramphenicol, and erythromycin were used at final concentrations of 100, 25, 20, and 200 μg ml−1, respectively, for E. coli. IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) and X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) were used, where appropriate, at concentrations of 0.1 and 40 μg ml−1, respectively. The incubation temperature for lactococci was 30°C, and that for E. coli was 37°C.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Characteristic(s) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis | ||

| NCDO 275 | Wild-type Lac+ strain | UCCa |

| MG1363 | Plasmid-free derivative of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris 712 | 17 |

| KK001 | Cured derivative of L. lactis NCDO 275 containing pCI2000 | This work |

| KK005 | MG1363 containing pCI214, Cmr | This work |

| KK006 | MG1363 containing pCI215, Cmr | This work |

| KK007 | MG1363 containing pCI216, Cmr | This work |

| KK009 | MG1363 containing pCI250, Cmr | This work |

| KK010 | MG1363 containing pCI250 (Cmr) and pMGparA (Emr) | This work |

| Escherichia coli XL1-Blue | recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 relA1 lac [F′ proAB lacIqZΔM15 Tn10 (Tetr)] | Stratagene |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCI341 | 3.1-kb replication probe vector, Cmr | 20 |

| pCI3330 | 4.0-kb replication probe vector, Emr | 20 |

| pUC18 | 2.7-kb E. coli positive selection vector, AprlacZ | New England Biolabs |

| pGKV210 | 4.4-kb promoter probe vector, Emr | 44 |

| pMG36e | 3.6-kb expression vector containing a P32 promoter | 43 |

| pCI2000 | 60-kb plasmid of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis NCDO 275 | UCCa |

| pCI201 | 5.588-kb EcoRI fragment of pCI2000 cloned into pCI341, Cmr | This work |

| pCI207 | 1.127-kb PCR product with PstI-XbaI incorporated sites cloned into pCI3330, Emr | This work |

| pCI210 | 5.588-kb EcoRI fragment of pCI201 cloned into pUC18, Apr | This work |

| pCI211 | 4.163-kb EcoRI-HindIII fragment of pCI201 cloned into pUC18, Apr | This work |

| pCI212 | pCI211 XbaI digested and religated (XbaI sites at 3653 and 5188 nt ligated) | This work |

| pCI214 | 1.4-kb EcoRI cat gene of pCI341 cloned into EcoRI-cleaved pCI211, Apr Cmr | This work |

| pCI215 | 1.4-kb XbaI-EcoRI cat gene of pCI341 cloned into EcoRI-XbaI-cleaved pCI212, Apr Cmr | This work |

| pCI216 | 1.4-kb XbaI cat gene of pCI341 ligated to the 6.3-kb XbaI fragment of pCI210 (contains pUC18), Apr Cmr | This work |

| pCI241 | 142-nt PCR product from primers 3912 and 4948, restricted with HindIII and cloned into pCI214 in the wild-type orientation, Cmr | This work |

| pCI250 | NsiI deletion derivative of pCI216, 4 nt removed from 3′ overhang at 1098 nt, Cmr | This work |

| pMGparA | pMG36e containing the parA gene of pCI2000, Emr | This work |

UCC, University College Cork stock culture collection.

Plasmid preparation and analysis.

The method of Anderson and McKay (4) was used for plasmid screening and isolation of DNA from lactococci. E. coli plasmid DNA was isolated by using the Qiaprep Spin Plasmid Miniprep kit (Qiagen, Ltd., Crawley, West Sussex, United Kingdom).

DNA manipulations.

The replication probe vector pCI341 (20) was used for the initial shotgun cloning of the EcoRI-digested pCI2000. Ligation mixtures were used to electroporate L. lactis MG1363 made competent by the method of Holo and Nes (24), by using a Genepulser apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, Calif.) following the conditions outlined in the manufacturer's manual. The E. coli positive selection vectors pUC18 and pUC19 (New England Biolabs, Hitchin, Hertfordshire, United Kingdom) were used for subclonings and cloning for sequencing. All restriction endonucleases, calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase, Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I, and T4 DNA ligase were supplied by Boehringer Corporation (Dublin, Ireland). Taq polymerase was supplied by Promega (Madison, Wis.) and used according to the supplier's instructions. Recovery of DNA fragments from agarose gels was achieved by using the Gene Clean II Kit (Bio 101, Vista, Calif.) as indicated in the supplier's manual. Ligation mixtures were transformed by the method of Dower et al. (13) into E. coli XL1-Blue (Stratagene). Blue-white screening was used for selection of plasmids carrying an insert.

DNA sequence analysis.

DNA sequence determination was performed with an Applied Biosystems 373A automated DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) with synthetic oligonucleotides (Oligo 1000M; Beckman Instruments, Inc., Fullerton, Calif.) as primers. Assembly of sequences was performed with the Seqman program of the DNASTAR software package. Database searches were performed with the FASTA (32) and BLASTN and TBLASTN (2) programs with sequences present in the following databases: SWISSPROT (release 30), NBRF-PIR (release 42), GenBank translated (release 86), and EMBL (release 38). Sequence alignments were performed by the Clustal method of the MEGALIGN program of the DNASTAR software package.

Plasmid stability studies.

Plasmid-containing L. lactis cultures were inoculated from stock in duplicate into fresh GM17 and grown for 12 h, after which they were diluted (1%) in fresh broth and incubated for another 12 h, with both transfers being performed in the presence of the appropriate selective antibiotic. These cultures were then additionally screened for plasmid content prior to the commencement of the experiment to ensure that the plasmid of interest was present. The strains were then continuously subcultured for 100 generations by dilution into fresh GM17 every 12 h in the absence of antibiotic selection. At the initial inoculation step, i.e., generation 0 (G0), and again after 12 h (G7) of growth, the cultures were serially diluted and plated on GM17 in the absence of antibiotic selection and incubated at 30°C for 48 h, after which 100 colonies were replica plated onto nonselective and selective plates and incubated at 30°C for 24 h. The reason for plating at generations G0 and G7 was to detect any skewness in the results due to the presence of antibiotic in the initial inoculum. Ten percent of the colonies corresponding to the antibiotic-resistant phenotype were picked off the duplicate nonantibiotic plates and screened for plasmid content to ensure the absence of spontaneous mutants. Platings were also performed at G50 and G100. The percentage loss of the test plasmid in the population could then be determined for G0, G50, and G100.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of the 5,588-nt EcoRI fragment of pCI2000 is available as GenBank accession no. AF154674.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Curing experiments and molecular cloning.

Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis NCDO 275 contains three plasmids designated pCI2000, pCI2001, and pCI2002. Southern analysis revealed that pCI2000 possibly contained an indeterminate origin of replication. When L. lactis NCDO 275 was successively subcultured in GM17 and GM17− to produce a variety of cured derivatives, one strain, designated KK001, which contained only pCI2000 was isolated.

The replication probe vector pCI341 was used for shotgun cloning of EcoRI-digested pCI2000 in L. lactis MG1363. A 5.6-kb EcoRI fragment was the smallest fragment initially identified which was capable of supporting replication of pCI341 in strain MG1363, and this recombinant clone was designated pCI201. The E. coli positive selection vector pUC18 was used to subclone the 5.6-kb EcoRI fragment of pCI201, which produced pCI210 (Fig. 1).

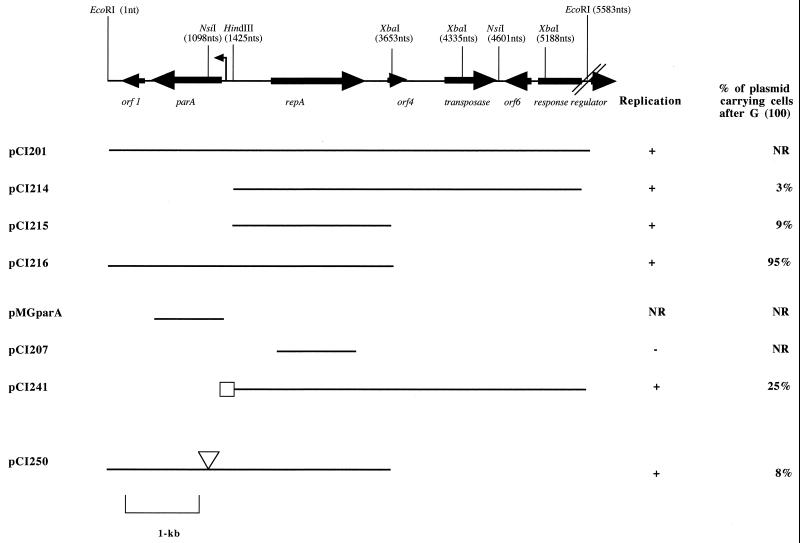

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the 5.586-kb EcoRI fragment of pCI2000 with the putative genes indicated. The putative promoter preceding the parA gene is indicated by a tall arrow. The fragments inserted into pUC18 containing the cat gene are presented below the map of the 5.588-kb EcoRI fragment. Those constructs capable of replicating in L. lactis MG1363 and the corresponding stability levels are indicated on the right. The box is indicative of the 142-bp region that was added to yield pCI241. The triangle shown for pCI250 marks the location of the frameshift mutation. NR, not relevant.

Identification and organization of ORFs.

The nucleotide sequence of the entire insert of pCI201 was determined (accession no. gb: AF154674), and it was shown to be 5,588 nt in length with a total GC content of 31%. Analysis of this sequence revealed the presence of seven putative open reading frames (ORFs) (Fig. 1 and Table 2). These were identified based on the adopted criteria that an ORF consists of at least 40 codons preceded by a potential Shine-Dalgarno sequence at an appropriate distance (6 to 15 bp) from one of the commonly used initiation codons (AUG, UUG, and GUG).

TABLE 2.

ORFs of pCI2000 and the homology exhibited by their potential protein products to amino acid sequences in the databases

| ORF (aa) | Location (nt) | Homology | % Similarity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORF 1 (76) | 4713–4486 | No homology | ||

| ORF 2 (263) | 5634–4846 | Orf57 parA homologue | 64 | 12 |

| ORF 3 (392) | 6349–7523 | Putative Rep | 65 | Unpublished (accession no. CAA90733) |

| ORF 4 (78) | 7840–8072 | Orf1 IS981 | 97 | 34 |

| ORF 5a (195) | 8459–8943 | Orf2 IS981 | 93 | 34 |

| ORF 6 (97) | 9054–9344 | OrfA IS1069 | 93 | 35 |

| ORF 7 (153) truncated | 9485–EcoRI site | Response regulator | 100 | 25 |

It is notable that although no obvious ribosome binding sequence precedes orf5, this potential ORF exhibits significant homology to the hypothetical ORFA of IS1069.

ORFs 2 and 3 show homology to partition and replication proteins, respectively.

Homology comparison to sequences in the database suggested that ORFs 2 and 3 are involved in plasmid stability and replication.

(i) ORF 2 (coordinates 489 to 1278).

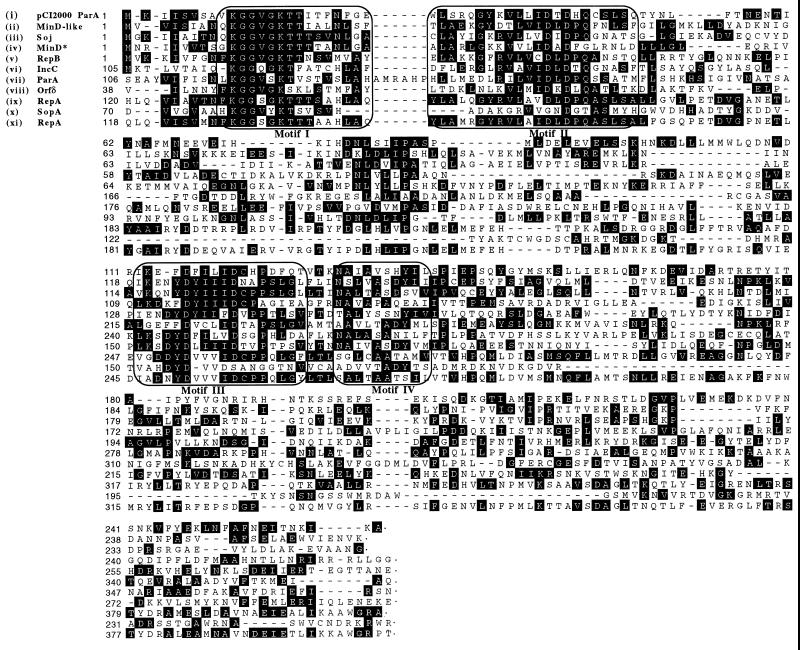

This ORF is preceded by a putative Shine-Dalgarno sequence (AAGG; ΔG = −8.4 kcal/mol) (43) and a potential promoter sequence (Fig. 2). The translated product shows extensive homology to the ParA family of ATPases which are involved in active partitioning. It contains the two conserved regions which show strong similarity to the consensus for an ATP-binding motif (motifs I and III [Fig. 3]). Amino acid alignments showed that the highest homology was to members of the chromosomally encoded ParA proteins (7, 9). Two further motifs (motifs II and IV) which, combined with the ATP-binding motifs, are characteristic and unique to this family of proteins (Fig. 3) are present (8, 30). In addition, there are a number of repeats located upstream of parA which have a potential to form secondary structures.

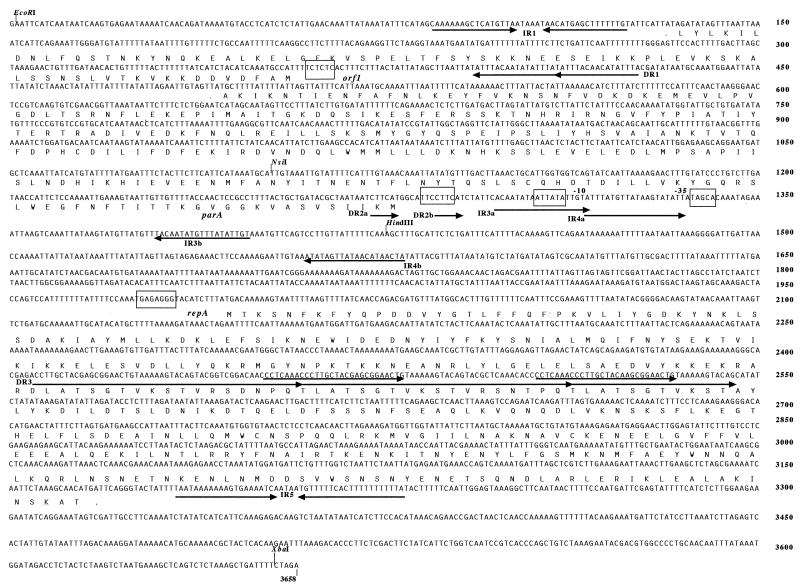

FIG. 2.

Coding sequence of the 3,653-nt fragment as defined by pCI216 comprising the partition and replication genes (Fig. 1). The deduced amino acid sequence is indicated underneath the coding sequence (orf4 is omitted as it is truncated on this subclone). Inverted repeats (IR) and direct repeats (DR) are indicated by arrowed lines and are located underneath the corresponding DNA sequence with the exception of IR2a, which is located above. Open boxes indicate the potential Shine-Dalgarno sequences. In addition, open boxes marked −10 and −35 delineate the putative promoter sequence of the parA gene. The coding sequence exhibited corresponds to nt 1 to 3653 of accession no. AF154674.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of the deduced amino acid sequence of parA of pCI2000 with a number of homologous proteins in the databases. (i) ParA pCI2000, accession no. AF154674. (ii) MinD-like putative chromosomal protein from Methanococcus jannaschii, accession no. Q60283. (iii) Soj chromosomal protein from Bacillus subtilis, accession no. P37522. (iv) MinD∗ putative chromosomal protein of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803, accession no. Q55900. (v) RepB of the enterococcal plasmid pAD1, accession no. B47097. (vi) IncC of the IncP plasmid R751, accession no. Q52312. (vii) ParA of the P1 plasmid of E. coli, accession no. P07620. (viii) Orfδ of pBT233, which is a derivative of the streptococcal plasmid pSM19035, accession no. CAAA45932. (ix) RepA protein of Agrobacterium tumefaciens pTiBS63, accession no. M24529. (x) SopA of the F plasmid, accession no. P08866. (xi) RepA protein of Agrobacterium rhizogenes pRiA4b, accession no. P05682. The framed boxes marked Motif I and Motif III represent the ATPase motif region I and region II. The framed boxes designated Motif II and Motif IV represent the additional motifs considered to be involved in protein-protein interactions or interaction with the cell membrane. The consensus amino acids are shaded black. This figure was adapted from the work of Motallebi-Vershareh et al. (30).

(ii) ORF 3 (coordinates 1993 to 3168).

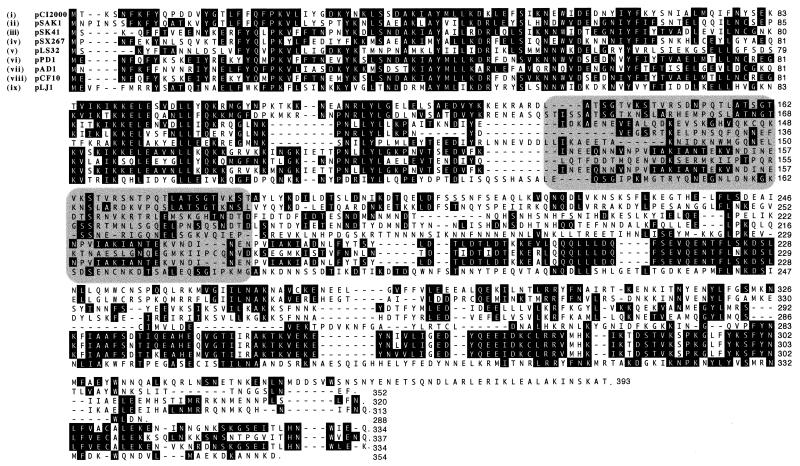

The potential 392-amino-acid protein product of orf3, which is divergently transcribed with respect to parA, shows extensive homology to the pLS32 family of replication proteins which includes those from the well-characterized homologous plasmids pAD1 (46), pPD1 (15), and pCF10 (23) of Enterococcus spp. and pSX267 (18) of Staphylococcus spp. (Fig. 4) and was therefore designated repA. Their sequences are highly homologous at the N terminus, but this homology disperses toward the central part of the protein. A 54-nt iteron, repeated two and one-half times, was evident within the deduced sequence of repA, and the iterons were similar in length, and the iterons were to those observed in pCF10 (Fig. 4). In the case of the homologous pLS32 and pSX267, the replication origin (ori) has been located within the repA gene, whereas the analogous iterons in pAD1 have been determined to represent a functional origin of transfer (oriT); the possibility of this region also functioning as an origin of replication has not yet been determined (3).

FIG. 4.

Comparison of the potential amino acid sequence of RepA of pCI2000 with putative members of the new family of plasmids as characterized by RepN of pLS32. The consensus amino acids are shaded black. The accession numbers in order of appearance are as follows: (i) AF154674, (ii) CAA90733, (iii) AAC61968, (iv) CAA63141, (v) D49467, (vi) D78016, (vii) A47092, (viii) A53309, and (ix) AAB52500. The grey-shaded area illustrates the 54-bp iterons which result in the 18-amino-acid repeat element.

Additional sequence information.

Five other ORFs were identified within the sequence of the 5,588-bp EcoRI fragment (Table 2). ORF 1 is transcribed in the same direction as par, and homology comparison with sequences in the database revealed no significant homology to any known proteins. Downstream of repA, a number of ORFs that show homology to sequences of insertion elements (ORF 4 to ORF 6) were found. The last ORF (ORF 7) is truncated at the C-terminal half. The first part of this ORF shows significant homology to response regulators of two-component systems.

Molecular subcloning of the origin of pCI2000.

In order to determine whether RepA is indeed the replication initiation protein of pCI2000 and to investigate the role of parA, a series of subclones of pCI201 was constructed. While pCI201 itself was stable, no subclones of this 5.6-kb fragment could be obtained in the replication probe vector pCI341 due to the formation of deletions. Therefore, pUC18 itself was utilized for further subcloning. When the relevant subclones were obtained (Table 1 and Fig. 1), the chloramphenicol (cat) gene from pCI341 was introduced to provide a selectable marker for use in Lactococcus. Three relevant subclones were obtained as follows. A 4.163-kb HindIII-EcoRI fragment of pCI201 was cloned into the HindIII-EcoRI sites of pUC18, resulting in pCI211. pCI211 was further digested with EcoRI and ligated to a 1.4-kb EcoRI cat fragment of pCI341, which generated pCI214. pCI216 contained the 6.3-kb XbaI fragment from pCI210 (which contained pUC18) and the pCI341-derived cat gene cloned as a 1.4-kb XbaI fragment (Fig. 1). The EcoRI-XbaI-digested pCI212 (Table 1) was ligated to the cat gene of pCI341 by using the same sites, resulting in pCI215. pCI215 harbors a DNA fragment of 2.228 kb which was the smallest cloned fragment capable of sustaining autonomous replication in L. lactis (Fig. 1).

parA is essential for stable plasmid inheritance.

In the absence of antibiotic selection, pCI216 was typically retained in 95% of the population after 100 generations. Plasmids pCI214 and pCI215 showed a marked decrease in stability with retention levels of 3 and 9%, respectively, after 100 generations (Fig. 1). In order to elucidate the role of parA in this observed instability, pCI250 was generated. This construct was produced by NsiI (1,098 nt) restriction of pCI216 and treating the protruding 3′ overhang with Klenow I fragment, generating blunt ends which were then religated and transformed into E. coli XL1-Blue. Sequence analysis revealed that the removal of 4 nt resulted in a frameshift of the parA gene, such that a stop codon was introduced after the initial 59 amino acids. pCI250 was then used to transform L. lactis MG1363, and the stability was determined. Only 8% of the population retained the plasmid after 100 generations in the absence of selective pressure.

ParA is active in trans.

To study whether ParA is active in trans, the par gene was cloned on a separate vector in the following manner: two oligonucleotides were designed to amplify the region from nt 490 to 1292, containing the entire par gene including the putative Shine-Dalgarno sequence. The 5′ oligonucleotide was supplied with a HindIII site, and the 3′ oligonucleotide was provided with an XbaI site to facilitate cloning. Following restriction with XbaI and HindIII, the PCR fragment was cloned into the same sites of pMG36e, generating pMGparA, in which parA was expressed under the control of the constitutive promoter P32 (45). This plasmid was used to transform KK009 (i.e., MG1363 containing pCI250), generating KK010. After continuous growth of KK010 for 100 generations in the presence of erythromycin but in the absence of chloramphenicol, it was found that pCI250 was retained in 98% of the cells.

The region upstream of parA contains several repeated elements that could act as a cis-acting centromeric site. To test this hypothesis, the region from nt 1425 to 1283 (Fig. 2) was generated via PCR and cloned into pCI214, creating pCI241. Although this plasmid showed some increase in stability (Fig. 1), no further increase in stability was observed when ParA was provided in trans. Therefore, this indicates that additional signals are required, possibly involving orf1 and/or DR1 (Fig. 1 and 2).

The origin of replication of pCI2000 is located outside the coding region.

For pLS32, it was shown elsewhere that the origin of replication was located within the coding sequence of repN (40). To determine whether this is also the case for pCI2000, PCR was employed to amplify the region from nt 2028 to 3158 (Fig. 2), with primers which had incorporated PstI and XbaI restriction sites. The PCR product, containing almost the entire coding sequence of rep but devoid of translation signals, was subsequently cloned into the replication probe vector pCI3330 (Emr) and transformed into E. coli XL1-Blue, resulting in pCI207. pCI207 was then electroporated into MG1363 containing pCI216. A positive control for this experiment was the promoter probe vector pGKV210 Emr which transformed MG1363 at a frequency of 104 μg of DNA. No transformants could be obtained when pCI207 was used. This result indicates that, in contrast to pLS32, these iterons alone do not act as an initiation site for replication on pCI2000. The significance of these repeats in pCI2000 is unknown. Moreover, the presence of an AT-rich region upstream of the repA gene of pCI2000 differs from the situation encountered on pLS32 (40) and suggests a possible relationship with class A replicons. Located downstream of repA is a 20-nt inverted repeat (IR5) at nt 3183 to 3227, which has a free energy value (ΔG) of −16.1 kcal/mol (42) (Fig. 2) and shows characteristics of a rho-independent terminator.

Distribution of parA and repA in lactococcal strains.

A total of 18 lactococcal strains from our laboratory collection, each harboring between two and six plasmids, was subjected to hybridization analysis to detect sequences homologous to repA and parA. When repA was used as a probe, a weak signal was obtained for only three plasmids from three strains, both larger than 15 kb (results not shown). Two of these three plasmids also exhibited a very weak signal for the parA locus.

Conclusion.

This study has identified a novel plasmid for the genus Lactococcus which appears to be a member of the pLS32 family of replicons (40). Southern analysis indicated that this replicon is rare in L. lactis strains. The partition mechanism associated with pCI2000 is also novel to Lactococcus and represents the first example of an active plasmid partitioning system for gram-positive bacteria. It is capable of stabilizing the unstable deletion derivative pCI250 in trans to a level comparable to that of the wild type. The cis-acting centromeric site has yet to be identified.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Aine Healy and Sinead Geary for oligonucleotide synthesis and DNA sequencing. We also acknowledge Benedict Moloney for his capable technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abeles A L, Friedman S A, Austin S J. Partition of unit-copy miniplasmids to daughter cells. III. The DNA sequence and functional organization of the P1 partition region. J Mol Biol. 1985;185:261–272. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90402-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schäffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped blast and psi-blast: a new generation of protein database search program. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.An F Y, Clewell D B. The origin of transfer (oriT) of the enterococcal, pheromone-responding, cytolysin plasmid pAD1 is located within the repA determinant. Plasmid. 1997;37:87–94. doi: 10.1006/plas.1996.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson D G, McKay L L. A simple and rapid method for isolating large plasmid DNA from lactic streptococci. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983;46:549–552. doi: 10.1128/aem.46.3.549-552.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brantl S D, Behnke D, Alonso J C. Molecular analysis of the replication region of the conjugative Streptococcus agalactiae plasmid pIP501 in Bacillus subtilis. Comparison with plasmids pAMβ1 and pSM19035. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:4783–4790. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.16.4783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruand C, le Chatelier E, Ehrlich S D, Janniere L. A fourth class of theta-replicating plasmids: the pAMβ1 family from Gram-positive bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11668–11672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bult C J, White O, Olsen G J, Zhou L, Fleischmann R D, Sutton G G, Blake J A, Fitzgerald L M, Clayton R A, Gocayne J D, Kerlavage A R, Dougherty B A, Tomb J-F, Adams M D, Reich C I, Overbeek C R, Kirkness E F, Weinstock K G, Merrick J M, Glodek A, Scott J L, Geoghagen N S M, Weidman J F, Fuhrmann J L, Nguyen D, Utterback T R, Kelley J M, Peterson J D, Sadow P W, Hanna M C, Cotton M D, Roberts K M, Hurst M A, Kaine B P, Borodovsky M, Klenk H-P, Fraser C M, Smith H O, Woese C R, Venter J C. Complete genome sequence of the methanogenic archaeon, Methanococcus jannaschii. Science. 1996;273:1058–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5278.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis M A, Radenedge L, Martin K A, Hayes F, Youngren B, Austin S J. The P1 ParA protein and its ATPase activity play a direct role in the segregation of plasmid copies to daughter cells. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:1029–1036. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.721423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Boer P A, Crossley R E, Hand A R, Rothfield L I. The MinD protein is a membrane ATPase required for the correct placement of the Escherichia coli division site. EMBO J. 1991;10:4371–4380. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb05015.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.del Solar G, Giraldo R, Ruiz-Echevarría M J, Espinosa M, Diaz-Orejas R. Replication and control of circular bacterial plasmids. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:434–464. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.2.434-464.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Vos W M. Genetic improvement of starter streptococci by the cloning and expression of the gene encoding for a non-bitter proteinase. In: Magnien E, editor. Biomolecular engineering in the European Community. Dordecht, The Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers; 1986. pp. 465–471. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dougherty B A, Hill C, Weidman J F, Richardson D R, Venter J C, Ross R P. Sequence and analysis of the 60 kb conjugative, bacteriocin-producing plasmid pMRC01 from Lactococcus lactis DPC3147. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:1029–1038. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dower W J, Miller J F, Ragsdale C W. High efficiency transformation of E. coli by high voltage electroporation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:6127–6145. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.13.6127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Firth N, Ridgway K P, Byrne M E, Fink P D, Johnson L, Paulsen I T, Skurray R A. Analysis of a transfer region from the staphylococcal conjugative plasmid pSK41. Gene. 1993;136:13–25. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90442-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujimoto S, Tomita H, Wakamatsu E, Tanimoto K, Ike Y. Physical mapping of the conjugative bacteriocin plasmid pPD1 of Enterococcus faecalis and identification of the determinant related to the pheromone response. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5574–5581. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.19.5574-5581.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gallie D R, Kado C I. Agrobacterium tumefaciens pTAR parA promoter region involved in autoregulation, incompatibility and plasmid partitioning. J Mol Biol. 1987;193:465–478. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90260-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gasson M J. Plasmid complements of Streptococcus lactis NCDO 712 and other lactic streptococci after protoplast-inducing curing. J Bacteriol. 1983;154:1–9. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.1.1-9.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gering M, Gotz F, Bruckner R. Sequence and analysis of the replication region of the Staphylococcus xylosus plasmid pSX267. Gene. 1996;182:117–122. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00526-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayes F, Austin S. Topological scanning of the P1 plasmid partition site. J Mol Biol. 1994;243:190–198. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayes F, Daly C, Fitzgerald G F. Identification of the minimal replicon of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis UC317 plasmid pCI305. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;55:3119–3123. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.1.202-209.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayes F, Vos P, Fitzgerald G F, de Vos W M, Daly C. Molecular organisation of the minimal replicon of novel, narrow-host-range, lactococcal plasmid pCI305. Plasmid. 1991;25:16–26. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(91)90003-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heath D G, An F Y, Weaver K E, Clewell D. Phase variation of Enterococcus faecalis pAD1 conjugation functions relates to changes in iteron sequence region. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5453–5459. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.19.5453-5459.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hedberg P J, Leonard B A, Ruhfel R E, Dunny G M. Identification and characterization of the genes of Enterococcus faecalis plasmid pCF10 involved in replication and in negative control of pheromone-inducible conjugation. Plasmid. 1996;35:46–57. doi: 10.1006/plas.1996.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holo H, Nes I F. High-frequency transformation, by electroporation, of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris grown with glycine in osmotically stabilized media. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:3119–3123. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.12.3119-3123.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khunajakr N, Liu C Q, Charoenchai P, Dunn N W. A plasmid-encoded two component regulatory system involved in copper-inducible transcription in Lactococcus lactis. Gene. 1999;229:229–235. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00395-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kiewiet R, Kok J, Seegers J F M L, Venema G, Bron S. The mode of replication is a major factor in segregational plasmid instability in Lactococcus lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:358–364. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.2.358-364.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kiewiet R, Bron S, de Jonge K, Venema G, Seegers J F M L. Theta replication of the lactococcal plasmid pWV02. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:319–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leenhouts K J, Tolner B, Bron S, Kok J, Venema G, Seegers J F M L. Nucleotide sequence and characterisation of the broad-host-range lactococcal plasmid pWV01. Plasmid. 1991;26:55–66. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(91)90036-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mori H, Kondo A, Ohshima A, Ogura T, Hiraga S. Structure and function of the F plasmid genes essential for partitioning. J Mol Biol. 1986;192:1–15. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90459-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Motallebi-Vershareh M, Rouch D A, Thomas C M. A family of ATPases involved in active partitioning of diverse bacterial plasmids. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1455–1463. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb02056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nordström K, Austin S J. Mechanisms that contribute to the stable segregation of plasmids. Annu Rev Genet. 1989;23:37–69. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.23.120189.000345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pearson W R, Lipman D J. Improved tools for biological sequence comparison. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;85:2444–2448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pillidge C J, Cambourn W M, Pearce L E. Nucleotide sequence and analysis of pWC1, a pC194-type rolling circle replicon in Lactococcus lactis. Plasmid. 1996;35:131–140. doi: 10.1006/plas.1996.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Polzin K M, McKay L L. Identification, DNA sequence, and distribution of IS981, a new, high-copy-number insertion sequence in lactococci. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:734–743. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.3.734-743.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rauch P J, Beerthuyzen M M, de Vos W M. Nucleotide sequence of IS904 from Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis strain NIZO R5. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:4253–4254. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.14.4253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seegers J F M L, Bron S, Franke C M, Venema G, Kiewiet R. The majority of lactococcal plasmids carry a highly related replicon. Microbiology. 1994;140:1291–1300. doi: 10.1099/00221287-140-6-1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Southern E M. Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J Mol Biol. 1975;98:505–517. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takiguchi R, Hashiba H, Aoyama K, Ishii S. Complete nucleotide sequence and characterization of a cryptic plasmid from Lactobacillus helveticus subsp. jugurti. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:1653–1655. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.6.1653-1655.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tanaka T, Ogura M. A novel Bacillus natto plasmid pLS32 capable of replication in Bacillus subtilis. FEBS Lett. 1998;422:243–246. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Terzaghi B E, Sandine W E. Improved medium for lactic streptococci and their bacteriophages. Appl Microbiol. 1975;29:807–813. doi: 10.1128/am.29.6.807-813.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tinoco I, Borer P N, Dengler B, Levine M D, Uhlenbeck O C, Crothers D M, Bralla J. Improved estimation of secondary structure in ribonucleic acids. Nat New Biol. 1973;246:40–41. doi: 10.1038/newbio246040a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van de Guchte M, van der Vossen J M B M, Kok J, Venema G. Construction of a lactococcal expression vector: expression of hen egg white lysozyme in Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:224–228. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.1.224-228.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van der Vossen J M B M, Kok J, Venema G. Construction of cloning, promoter-screening, and terminator-screening shuttle vectors for Bacillus subtilis and Streptococcus lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985;50:540–542. doi: 10.1128/aem.50.2.540-542.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van der Vossen J M, van der Lelie D, Venema G. Isolation and characterization of Streptococcus cremoris Wg2 specific promoters. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:2452–2457. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.10.2452-2457.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weaver K E, Clewell D B, An F. Identification, characterization, and nucleotide sequence of a region of Enterococcus faecalis pheromone-responsive plasmid pAD1 capable of autonomous replication. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1900–1909. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.7.1900-1909.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Williams D R, Thomas C M. Active partitioning of bacterial plasmids. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:1–16. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]