Abstract

Background

The nasopharyngeal swab is the gold standard collection method for COVID-19, but is invasive and painful, subsequently resulting in poor patient acceptance. This investigation explores the process of developing and validating an alternative respiratory pathogen collection device that relies on a nasopharyngeal irrigation mechanic. The primary objective was to determine if sufficient pathological sampling can be achieved by mechanism of nasopharyngeal irrigation that is proportionate to the nasopharyngeal swab method.

Methods

The study device was designed using Shapr3D modeling software and fabricated on a fused deposition modeling printer. Fifteen participants were enrolled with each receiving a saline nasopharyngeal washing using the study device. Specimen adequacy was evaluated by two real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing methods to identify the presence of the human RNase P gene. Results were evaluated quantitatively through interpretation of the PCR cycle threshold (Ct).

Results

All 15 specimens tested positive for the presence of RNaseP, demonstrating specimen cellularity, adequate extraction of nucleic acids, and the absence of inhibitors to amplification. The mean Ct value was 29.5 (Applied Biosystems TaqPath RT-qPCR) and 30.7 (NECoV19). All participants felt the study device irrigation procedure was faster than the nasopharyngeal swab, with none experiencing any discomfort from the irrigation mechanism.

Conclusion

The importance of early diagnostic testing and its role in countermeasures for communicable diseases such as COVID-19 is well established in the literature. Innovation to bolster our testing infrastructure is more important now than ever. This study was successful in developing and validating an alternative nasopharyngeal respiratory pathogen collection device that utilizes fluid debridement as its core mechanic. Data from this pilot study demonstrated the study device was successful in producing high-quality specimens for PCR testing. Feedback from the study participants was also in favor of the study device when compared to the nasopharyngeal swab.

Keywords: Respiratory virus, Self-collection respiratory pathogen device, COVID-19

1. Introduction

Widespread diagnostic testing for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) continues to be a limiting factor in efforts to accurately project case numbers and inform public health response to contain coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Global supply and personnel shortages stifled the deployment of testing options for patients, hindering downstream processes such as contact tracing and containment [1,2]. With the resurgence of endemic respiratory tract infections (RTI) such as influenza [3], it is paramount to have reliable alternative testing modalities to bolster the current infrastructure.

The nasopharyngeal (NP) swab is the standard collection method for SARS-CoV-2 [4], due to data suggesting a higher viral concentration in the nasal cavity [5]. However, the literature suggests lower patient acceptance of the NP swab collection method [6] with procedural discomfort contributing to the low acceptance rate [7]. The NP swab collection procedure is traumatizing for patients as it requires deep probing of the posterior nasopharynx with a stiff swab applicator. The nasopharyngeal swab procedure has been known to cause pain and injuries such as epistaxis [8]. Additionally, there is also a considerable infection risk to healthcare workers administering the nasopharyngeal swab as patients tend to cough or sneeze during the procedure [9]. A potential solution is to offer patients an alternative collection method that is more comfortable and can produce adequate specimens for diagnostic testing.

This paper explores the process of developing and validating an alternative respiratory pathogen collection device. Industry development principles such as Design Control Guidance for Medical Device Manufacturers was adopted as a guide for the prototyping of the study devices [10]. Design control is a development principle endorsed by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to facilitate the development of medical grade equipment [10].

In exploring a potential alternative nasopharyngeal specimen collection method, a team of emergency medicine researchers developed the concept of nasopharyngeal debridement using fluid irrigation. This alternative respiratory pathogen collection device (study device) was designed to be self-administered by the patient but also be administered by a healthcare professional. The study device irrigates the patient's nasopharyngeal cavity with saline, debriding epithelial cells potentially harboring respiratory pathogens. The irrigation solution is immediately recaptured into a self-contained chamber within the study device, minimizing the need to handle infectious bodily fluids.

The primary project question is whether sufficient specimen collection can be achieved by mechanism of nasopharyngeal irrigation that is proportionate to the nasopharyngeal swab method. It is also postulated that, the replacement of the traditional nasopharyngeal swab with a fluid debridement mechanic will result in higher patient acceptance.

Using data collected from wound care literature, it was determined the optimal irrigation pressure is 5–15 pounds per square inch (PSI), which is sufficient to overcome the pathogen adhesion threshold [[11], [12], [13]]. Engineering considerations were incorporated into the study device to ensure a consistent irrigation pressure of 10–20 PSI, but not to exceed 30 PSI. Five specimens were collected from members of the development team, followed by microscopic examination of the specimens to access for the presence of epithelial cells. The presence of epithelial cells is often used as a measurement for specimen adequacy and is accepted as a precursor for pathogens [14]. Three of the five (60%) specimens demonstrated the presence of epithelial cells under microscopic examination. This suggested the process of fluid debridement may be a potential alternative to mechanical debridement with a nasopharyngeal swab.

This study is a follow-up pilot evaluation of the study device to further expand on the feasibility study. In this study, 15 participants were enrolled from a pool of emergency medicine staff, including physicians, nurses, care technicians, and medical scribes.

Specimens were tested for the presence of RNase P which is supported in the literature as an objective measurement of specimen adequacy [7].

2. Methods

2.1. Study approval

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the organization's Institutional Review Board (IRB). The study proposal was also approved by a COVID-19 Research Steering Committee, Investigational Device Review Committee, and The Human Subjects Research Safety Review Committee.

2.2. Participant enrollment

Study participants were enrolled from a convenient sampling of emergency department staff during their shift. Study inclusion criteria included: 1) age 19 years or older, and 2) current staff members of the emergency department.

2.3. Study device fabrication

All study devices were designed using Shapr3D software and fabricated on an Ultimaker S3 brand fused deposition modeling (FDM) 3D printer. The study devices were printed in Ultimaker brand polylactic acid (PLA) material. PLA material was selected because it is a biodegradable vegetable-based polymer-blend composed primarily of cornstarch, but more importantly, it is non-toxic and safe for human use.

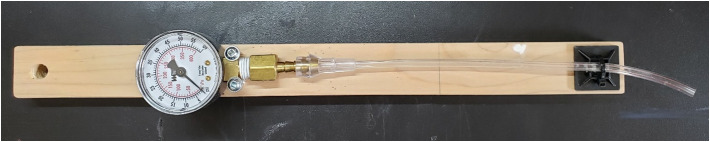

A total of 20 study devices were manufactured and subjected to a quality control process including evaluation of 1) print quality and integrity, 2) fit of the individual components, and 3) pressure testing. Each study device received three pressure tests with the mean outcome recorded as the final pressure measurement for the respective device. The first 15 study devices tested passed all quality control parameters and were used on enrolled participants. The medical air delivery system equipped in most emergency departments and the Anest Iwata compressed air conversion factors [15] was used to develop a PSI control for pressure testing.

All study devices were sanitized using PDI P13872 sanitation wipes, allowed to air dry, then sealed inside a specimen bag along with a prefilled 5 ml syringe and a 15 ml centrifuged tube.

2.4. Specimen collection process

To ensure consistency in the specimen collection process, all irrigation procedures were administered by the study personnel.

After the irrigation process was completed, the recollected specimens were transferred from the study device into a capped 15 ml conical centrifuge tube for transport.

2.5. Specimen evaluation process

Each study device collected sample was tested for adequacy using both an internal control and an external control. Testing for both controls was performed real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR). Evaluation of the presence of human RNase P gene expression as an internal control serves to confirm specimen cellularity, adequate extraction of nucleic acids, and intact amplification. For this study, the presence of RNase P in each sample was tested using two different rRT-PCR reagent master mixes (Applied Biosystems™ TaqPath™ 1-Step RT-qPCR Master Mix, CG and Invitrogen™ SuperScript™ III Platinum™ One-Step qRT-PCR Kit). To further evaluate the adequacy of the samples collected using the study device, MS2 bacteriophage (ATCC 15597-B1) was added as an external control to each sample prior to rRT-PCR testing.

Nucleic acid was extracted from each sample using the MagMAX Viral/Pathogen Nucleic Acid Isolation kit (Applied Biosystems) on the KingFisher Flex (ThermoFisher Scientific) extraction instrument. The extracted RNA, if present, was reverse-transcribed to form cDNA, which is then amplified by PCR using primers and probes specific to the RNase P gene, or MS2 bacteriophage gene target. The presence of a gene target in the sample is determined by the quantitative cycle threshold (Ct) value. The Ct is reported at the intersection between an amplification curve and an empirically determined threshold representing the number of cycles of amplification required to detect the fluorescence of a product of the PCR reaction. The value is reported numerically and can be interpreted as a relative measure of the starting concentration of the gene target in the original specimen. A lower Ct typically correlates with a higher starting concentration of the targeted gene.

2.6. Statistical analysis

For a single cohort non-comparison pilot study, it was determined 15 samples would provide sufficient power to identify an intervention effect. The decision to enroll 15 participants was also based on lean manufacturing principles in which batch manufacturing can facilitate the rapid validation of a particular design parameter to guide the development process. Data from this pilot study is reported using descriptive statistics.

3. Results

A total of 15 participants were enrolled in the study. On average, the study device recollected approximately 3.1 ml of the 5 ml of saline used during the irrigation process. All 15 participants felt the study device irrigation procedure was faster than the nasopharyngeal swab based on their own experiences with administering or receiving a nasopharyngeal swab. None of the participants reported experiencing any discomfort from the irrigation mechanism. Four participants have had a nasopharyngeal swab collection previously, with all reporting the study device collection was more comfortable.

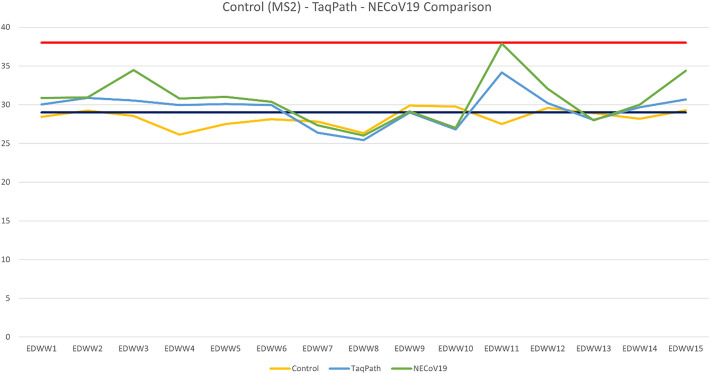

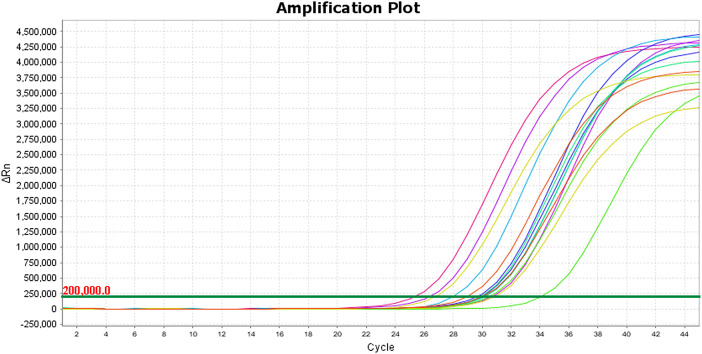

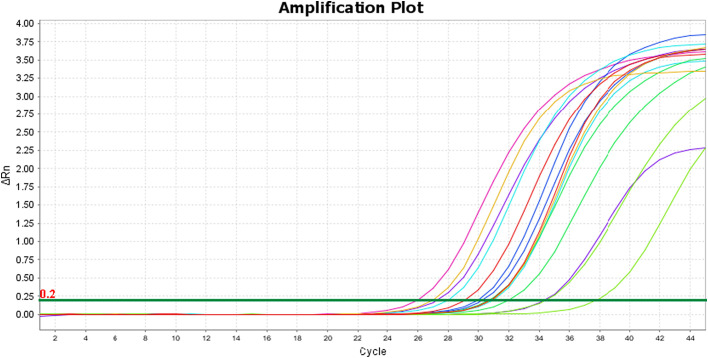

Three separate rRT-PCR tests were performed on each study specimen. In the first test, all 15 specimens (100%) demonstrated adequate amplification of the MS2 bacteriophage external control, indicating there was no contamination of the irrigated saline (wash) or 3D printed material with any exogenous substance that could inhibit PCR amplification. The rRT-PCR tests using the Applied Biosystems™ TaqPath™ 1-Step RT-qPCR Master Mix, CG and the Invitrogen™ SuperScript™ III Platinum™ One-Step qRT-PCR Kit reagents were conducted on test runs two and three, respectively. All specimens in the second and third test runs demonstrated adequate amplification of the human RNase P gene target with respective mean Ct values of 29.5 and 30.7. Both tests had the same distribution of specimens with strong amplification (26.67%), adequate amplification (73.33%), and weak or no amplification (0%) (Fig. 5). The amplification plots for the RNase P tests are illustrated in Fig. 3, Fig. 4, each test had a threshold of 0.200 delta Rn. The Ct values for each test are reported in Table 1 (See Fig. 1, Fig. 2).

Fig. 5.

CT values from each batch. Values above the red line indicates weak or negative gene amplification, values between the red and black lines indicates adequate gene amplification, and values below the black line indicates strong gene amplification. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 3.

Amplification plot for RNase P TaqPath test.

Fig. 4.

Amplification plot for RNase P SuperScript test.

Table 1.

CT values for each PCR test on study specimen. CT values cutoff set at 35.

| Study samples | Control CT values (MS2 gene target) | TaqPath CT values (RNase P gene target) | SuperScript CT values (RNase P gene target) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 28.441 | 30.041 | 30.872 |

| 2 | 29.254 | 30.891 | 30.927 |

| 3 | 28.548 | 30.548 | 34.466 |

| 4 | 26.143 | 29.947 | 30.791 |

| 5 | 27.519 | 30.102 | 31.022 |

| 6 | 28.133 | 29.95 | 30.364 |

| 7 | 27.821 | 26.394 | 27.341 |

| 8 | 26.341 | 25.443 | 26.019 |

| 9 | 29.905 | 29.003 | 29.134 |

| 10 | 29.75 | 26.794 | 27.011 |

| 11 | 27.514 | 34.153 | 37.886 |

| 12 | 29.575 | 30.214 | 32.049 |

| 13 | 28.92 | 28.048 | 27.999 |

| 14 | 28.185 | 29.664 | 30.008 |

| 15 | 29.273 | 30.684 | 34.4 |

Fig. 1.

Study device attached to a 5 ml syringe.

Fig. 2.

PSI test gauge.

4. Discussion

The nasopharyngeal cavity has consistently demonstrated a higher viral concentration for the SARS-CoV-2 virus and is endorsed by the CDC as the diagnostic standard for COVID-19 testing [4,5]. A small study in China demonstrated the potential for improved diagnostic sensitivity for COVID-19 when the nasopharyngeal cavity was premoistened before swabbing for the SARS-CoV-2 virus [16]. When considering most laboratories are equipped with PCR testing instruments calibrated for nasopharyngeal samples, we felt it was wise to explore alternative collection methods for nasopharyngeal specimens. Drawing from our experience as emergency medicine clinicians, we applied the principles of wound irrigation to develop the study device. Through our literature review, we were able to determine the optimal irrigation pressure (5–15 PSI) to debride tissue surfaces for pathogens and was successful in engineering a device that adhered to these parameters. We acknowledge the irrigation pressure is dependent upon the plunger force as applied by the user and may result in discrepancies in the irrigation pressure. To ensure consistency the inner bore of the irrigation tip incorporated a gradual taper from 2 mm to 1 mm at the distal end. The taper was carried over the length of 30 mm. This tapered design ensured an irrigation pressure of 10 PSI so long as a steady plunger force was applied, while not exceeding 30 PSI even under maximal plunger force.

Data from our feasibility study was supportive of the study hypothesis but we acknowledge the limitations of our study design. This was the basis for our follow up pilot study where a larger sample size was enrolled, but more importantly, we employed an objective measurement for specimen quality by testing for the presence of RNase P. Along with the presence of RNase P, which was detected in 100% of our samples, we also utilized the CT value as an additional objective measure for specimen adequacy. CT values between 37 and 40 are generally considered the cutoff range for PCR testing, indicating a negative specimen [7,17,18]. In our study, we established a cutoff CT value of 35. Our study specimens demonstrated a consistently low CT value with 73.33% indicating adequate amplification and 26.67% indicating strong amplification of the target gene [17,18]. This data suggests our study device was successful in producing high quality specimens.

We feel further research is needed to continue our evaluation of this alternative collection method. We acknowledge the potential for a false negative outcome in our data as the presence of bacterial deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) could in theory trigger a positive RNase P finding. Nevertheless, the presence of bacteria in our specimens is a confirmatory indicator of success in overcoming the pathogen adhesion threshold. This means debridement for the SARS-CoV-2 virus is also possible. Since our device is intended to fulfill a gap in RTI diagnostic testing, it is sensible for us to evaluate the diagnostic fidelity of our device when compared to the standard collection method in RTI cases – the nasopharyngeal swab. A prospective study comparing diagnostic outcomes for viral PCR testing is the logical next step.

5. Conclusion

The importance of early diagnostic testing and its role in countermeasures for communicable diseases such as COVID-19 is well established in the literature. Innovation to bolster our testing infrastructure is more important now than ever. Using the principles of fluid debridement, we were successful in developing an alternative nasopharyngeal respiratory pathogen collection device. Data from this pilot study demonstrated the study device was successful in producing high-quality specimens for PCR testing. Feedback from the study participants was also in favor of the study device when compared to the nasopharyngeal swab.

Financial support

This project was funded by the University of Nebraska Medical Center – COVID Rapid Response Grant

Author contributions

TTN: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing- original draft, Writing-review...editing.

WGZ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing-review...editing

MCW: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing-review...editing

ATS: Conceptualization, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing-review...editing

ANB: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing- original draft, Writing-review...editing

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Thang T. Nguyen: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Wesley G. Zeger: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization. Michael C. Wadman: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization. Andy T. Schnaubelt: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Aaron N. Barksdale: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Footnotes

Moderated Poster presentation: Society of Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM) Annual Meeting, New Orleans, Louisiana, May 13, 2022.

References

- 1.Santiago I. Trends and innovations in biosensors for COVID-19 mass testing. ChemBioChem. 2020;21:1–11. doi: 10.1002/cbic.202000250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walensky P.R., Rio C. From mitigation to containment of the COVID-19 pandemic: putting the SARS-CoV-2 genie back int the bottle. JAMA. 2020;19(323):1889–1890. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weekly U.S. influenza surveillance report (FluView) The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/index.htm Retrieved from: [Google Scholar]

- 4.Interim guidelines for collecting, handling, and testing clinical specimens from persons for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Center Disease Contr Prevent; 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/guidelines-clinical-specimens.html Retrieved from: [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zou L., Ruan F., Huang M., Liang L., Huang Z., Hong Z., et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(12) doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seaman P.C., Tran T.L., Cowling J.B., Sullivan G.S. Self-collected compared with professional-collected swabbing in the diagnosis of influenza in symptomatic individuals: a meta-analysis and assessment of validity. J Clin Virol. 2019;118:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2019.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goyal S., Prasert K., Praphasiri P., Chittaganpitch M., Waicharoen S., Ditsungnoen D., et al. The acceptability and validity of self-collected nasal swabs for detection of influenza virus infection among older adults in Thailand. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2017;11:412–417. doi: 10.1111/irv.12471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fabbris, C., Cestaro, W., Menegaldo, A., Spinato, G., Frezza, D., Vijendren, A., Borsetto, D., & Boscolo-Rizzo, P. Is oro/nasopharyngeal swab for SARS-CoV-2 detection a safe procedure? Complications observed among a case series of 4876 consecutive swabs. Am J Otolaryngol. 42(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.To K., Tsang O., Leung W., Tam A., Wu T., Lung D., et al. Temporal profiles of viral load in posterior oropharyngeal saliva samples and serum antibody responses during infection by SARS-CoV-2: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Disease. 2020;5(20):565–574. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30196-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Design control guidance for medical device manufacturers. FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health; 1997. https://www.fda.gov/media/116573/download Retrieved from: [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fry E.D. Pressure irrigation of surgical incisions and traumatic wounds. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2017;18(4):1–2. doi: 10.1089/sur.2016.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ball S. Optimal pressures and irrigation techniques in small-animal wound management. Veterin Nurs J. 2017;32(11):325–328. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barnes S., Spencer M., Graham D., Johnson B.H. Surgical wound irrigation: a call for evidence-based standardization of practice. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42:525–529. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akmatov K.M., Gatzemeier A., Schughart K., Pessler F. Equivalence of self- and staff-collected nasal swabs for the detection of viral respiratory pathogens. Plos One. 2012;11(7):1–7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Compressed air conversion factors. Anest Iwata USA. 2005. Retrieved from:http://anestiwata.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/air-flow-conversion.pdf.

- 16.Han H., Luo Q., Mo F., Long L., Zheng W. SARS-CoV-2 RNA more readily detected in induced sputum than in throat swabs of convalescent COVID-19 patients. Lancet. 2020;20:655–665. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30174-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oswald N. What is a Cq(Ct) value? BiteSizeBio. 2020 https://bitesizebio.com/24581/what-is-a-ct-value/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- 18.An overview of cycle threshold values and their role in SARS-CoV-2 real-time PCR test interpretation. 1-14. Public Health Ontario; 2020. https://www.publichealthontario.ca/-/media/documents/ncov/main/2020/09/cycle-threshold-values-sars-cov2-pcr.pdf?la=en Retrieved from: [Google Scholar]