Abstract

Objective

To identify factors related to turnover intent among direct care professionals in nursing homes during the pandemic.

Methods

Cross-sectional study with surveys administered via an employee management system to 809 direct care professionals (aides working in nursing homes). Single items assessed COVID-19-related work stress, preparedness to care for residents during COVID-19, job satisfaction, and intent to remain in job. A two-item scale assessed quality of organizational communication.

Results

Path analysis demonstrated that only higher job satisfaction was associated with a higher likelihood of intent to remain in job. Higher quality of employer communication and greater preparedness were also associated with higher job satisfaction, but not with intent to remain. Higher quality communication and greater preparedness mediated the negative impact of COVID-19-related work stress on job satisfaction.

Conclusion

Provision of high-quality communication and training are essential for increasing job satisfaction and thus lessening turnover intent in nursing homes.

Keywords: Nursing homes, Certified nursing assistants, Aides, Job satisfaction, Turnover intent, Turnover, COVID-19, Staff shortage

Introduction

An estimated 4.6 million direct care professionals who care for older adults and people with disabilities in nursing homes, residential settings, and in their homes found themselves on the frontline of the COVID-19 pandemic.1 Direct care professionals provide the vast majority of hands-on assistance to these vulnerable populations and play a critically important role in helping care recipients remain healthy, maintain their independence, and avoid unnecessary use of expensive health care services.2 Direct care professionals are particularly susceptible to contracting COVID-19 and are at increased risk of severe illness if they become infected with the virus. These exacerbated risks in direct care professionals are directly associated with daily exposure to residents and clients who have been infected with the virus, living in communities with high rates of COVID-19, belonging to demographic groups (i.e., people of color and older adults) that are at high risk of contracting the virus, using public transportation, and working multiple jobs.3, 4, 5 Further, employees in nursing homes, including direct care professionals, faced additional stressful work-specific and competing external challenges, including increased workload demands, understaffing, emotional burden of caring for residents facing significant isolation, illness, and death, separation from family members, managing personal needs and family demands, and experiencing financial hardship.6 , 7 , 8 Many of these challenges existed prior to the pandemic, but COVID-19 has exacerbated these issues. Considering the stresses and challenges encountered, it comes as no surprise that direct care professionals’ mental health has been negatively impacted during the pandemic.9, 10, 11

The negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on direct care professionals in nursing homes increased the high turnover and staff shortages in nursing homes that were already prevalent before the pandemic.12, 13, 14, 15, 16 These staffing shortages have a wide-ranging impact. First, shortages result in even more staff leaving their positions.17 Staffing levels and turnover also impact quality of care in nursing homes. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, more optimal staffing levels were associated with better nursing home quality outcomes.18 During the pandemic, more optimal staffing levels were linked with reduced likelihood of experiencing a COVID-19 outbreak and fewer COVID-19-relate deaths in nursing homes.19 , 20 Further, high staff turnover rates in nursing homes have been found to be associated with undesirable resident health outcomes (e.g., higher odds of pressure ulcers) as well as with care satisfaction.21 , 22 Hence, nursing homes need to maintain optimal staffing levels and have low turnover rates to ensure most optimal well-being for their residents and staff. It is, therefore, important to study factors associated with turnover in nursing homes, particularly during the highly stressful period of the COVID-19 pandemic. Intent to remain or intent to leave one's job, also sometimes referred to as turnover intent, is highly correlated with actual turnover and has, therefore often been used in research as a proxy for turnover.23 , 24 Studying factors associated with intent to leave one's job as opposed to actual turnover has the advantage that if modifiable factors of intent to leave can be identified, employers can intervene with employees who voice intent to leave before they resign and, thus, can potentially prevent employees from resigning.

Conceptual model and hypotheses of the current study

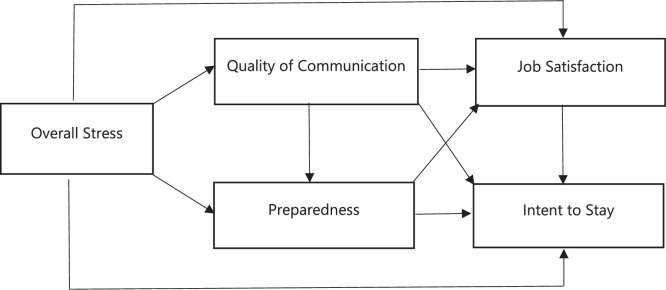

Previous research on nursing home direct care professionals’ intent to leave conducted before the pandemic delineated conceptual frameworks involving a variety of factors influencing direct care professionals’ intent to leave their job, including personal characteristics (e.g., ethnicity), role-related characteristics (e.g., tenure), job characteristics (e.g., work schedule, work content, job satisfaction), organizational characteristics (e.g., facility size, training, quality of workplace supports), and availability of jobs.23 One factor that has been consistently shown to be associated with both decreased likelihood of intent to leave and actual turnover among nursing assistants working in long-term care is higher job satisfaction.23 , 25, 26, 27 A main driver of job satisfaction is job competency, which is defined as having the knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary to perform one's job which has also been found to be directly associated with intent to leave.25 , 28 Therefore, it is not surprising that perceptions of better training has been found to be associated with higher job satisfaction and lower intent to leave.23 Plus, pre-pandemic research has also shown that in nursing homes, open communication by nursing home leadership was linked to more optimal staff performance.29 Studies conducted during the pandemic found that organizational communication and organizational supports (e.g., support from a supervisor) are important factors influencing nursing home employees’ ability to work under the challenging conditions of the COVID-19 pandemic.30 , 31 Our own research conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated that high quality employer communication around COVID-19, and nursing home employees’ more optimal preparedness to care for residents as a result, was associated with a decrease in the likelihood of leaving the job over a six-month period.6 However, in this previous study job satisfaction as a potential mediator in the relationship of organizational supports on job resignation was not included and turnover intent (a potentially modifiable variable) was not used as an outcome. Hence, the purpose of the current study was, in a sample of nursing home direct care professionals, to examine the interrelationships between overall COVID-19 work-related stress, quality of employer communication around COVID-19, direct care professionals’ perceived preparedness to care for residents with COVID-19, their job satisfaction, and intent to remain in their job. Figure 1 depicts the study's conceptual model which was delineated based on prior models of turnover intent and the above cited research findings. Based on this conceptual model, the following relationships among study variables were hypothesized:

-

1.

Higher levels of stress will be associated with lower levels of perceived preparedness. However, higher quality of communication will mediate the negative effects of stress on preparedness.

-

2.

Higher quality of employer communication will be associated with more optimal preparedness. Further, both higher quality of employer communication and more optimal preparedness will be associated with higher job satisfaction as well as with higher likelihood of intent to remain on the job.

-

3.

Higher job satisfaction will be associated with higher likelihood of intent to remain.

-

4.

Higher levels of stress will also be associated with lower levels of job satisfaction and lower likelihood of intent to remain in one's job. However, higher quality of employer communication and more optimal preparedness will separately mediate [a] the negative effect of stress on job satisfaction and [b] the negative effect of stress on intent to remain.

Fig. 1.

Study Conceptual Model.

Methods

Study design

This was a descriptive study with a cross-sectional design aiming to gauge the experiences of nursing home direct care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic in May 2020.

Sample

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the study sample, which included 809 nursing home direct care professionals (aides working in nursing homes) who were employed in May 2020. On average, direct care professionals had been employed for approximately 1.4 years. WeCare ConnectTM does not capture socio-demographic characteristics of employees. However, data regarding characteristics of the nursing homes where these direct care professionals worked were obtained. The majority (77%) of direct care professionals were employed by non-profit nursing homes. The vast majority (94%) of direct care professionals worked at either medium sized (50-99 beds) or large sized (100+ beds) nursing homes, 46% and 48%, respectively. Forty-seven percent of direct care professionals worked at nursing homes that were in urban areas, 42% in suburban nursing homes, and 12% in rural nursing homes.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Work-Related and Nursing Home Characteristics (N=809)

| n (%) | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Care Professionals Work-Related Characteristics | |||

| Overall perceived stress level | 2.87 | 1.32 | |

| Perceived level of employee preparedness | 4.13 | 1.11 | |

| Perceived quality of communication how to care for residents | 4.37 | .97 | |

| Perceived quality of communication regarding how to protect yourself and family | 4.36 | .99 | |

| Overall perceived quality of employee-related communication | 8.73 | 1.87 | |

| Length of employment | 1.41 | 3.93 | |

| Job satisfaction | 4.16 | .96 | |

| Intent to remain in job (Yes) | 535 (90.7) | ||

| Nursing Home Characteristics | |||

| Location of facility | |||

| Rural | 93 (11.6) | ||

| Urban | 334 (41.7) | ||

| Suburban | 374 (46.7) | ||

| Nursing home size | 119.01 | 79.27 | |

| Small (< 50 beds) | 46 (5.8) | ||

| Medium (50-99 beds) | 364 (45.9) | ||

| Large (100+ beds) | 383 (48.3) | ||

| Ownership status | |||

| For profit | 186 (23.0) | ||

| Non-profit | 623 (77.0) |

Procedures

Study data were collected via an employee engagement and management system called WeCare ConnectTM which is utilized by 165 aging services providers at 1000+ locations around the United States. WeCare ConnectTM supports organizations in better understanding staff members’ challenges with onboarding, training, supervisory relationships, job fit, expectations, and the physical and organizational environment. WeCare ConnectTM obtains ongoing feedback from employees which is used to facilitate continuous quality improvement. To obtain the study data on the impact of COVID-19 in nursing homes, WeCare ConnectTM – for the month of May 2020 - added questions designed by the study team to their employee interview battery. WeCare ConnectTM surveys, which are active for 30 days, are first distributed via email and text. Within seven days, employees receive two reminders to complete the survey. After seven days, if not completed, employees are called, and the survey is conducted via phone. These data collection methods resulted in an overall response rate of 80% and above across all employees. This study analyzed data from a sub-sample of direct care professionals (aides) from the nursing home data file. The study was deemed “Not Human Subjects Research” by the Internal Review Board of the researchers’ institution (IRB# 2020174).

Measures

Overall COVID-19-related work stress was assessed with one item asking participants to rate how stressed they felt overall as an employee during the COVID-19 pandemic on a scale from 1-5 (1= not stressed at all; 5 = extremely stressed). Two questions assessed quality of organizational/employer communication around COVID-19. One question asked participants to rate their organization's communication with them regarding how to protect themselves and their family during the COVID-19 pandemic (1=does not keep us informed at all; 5=keeps us fully informed). The other question asked participants to rate the quality of their organization's communication with them regarding how to care for residents and protect them during the COVID-19 pandemic (1=does not keep us informed at all; 5=keeps us fully informed). Scores on the two items were summed to obtain one indicator of quality of employer communication. Cronbach's α for the two-item scale for the current sample was .91. To assess direct care professionals’ perceived preparedness to care for residents during COVID-19, one item asking participants to rate overall how prepared they felt to care for a resident with known or suspected COVID-19 (1=not prepared at all; 5=extremely prepared) was utilized. Job satisfaction was measured with a one-item indicator asking participants to rate how satisfied they are with their current job (1=not at all satisfied; 5=very satisfied). The outcome variable intent to remain on the job was assessed with one question: “Do you see yourself working for us one year from now?” (1=Yes; 0=No). Two covariates – nursing home size and job tenure – were assessed. Number of beds in the nursing homes that direct care professionals worked at was used as an indicator of nursing home size. Job tenure was measured by length of employment at the current nursing home in years.

Data analysis plan

Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, percentages) were computed for all study variables to ensure normality in the distribution of the data. To test study hypotheses based on the study's conceptual model, a path analysis using a structural equation modeling approach was conducted. Assessment of direct and indirect effects followed published guidelines.32, 33, 34, 35, 36 Bootstrapping, a nonparametric resampling approach used with replacement that can mitigate issues surrounding low power and non-normality, was used to derive 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals with 5,000 bootstrapped resamples.34 Bootstrapping approaches require no missing data, thus multiple imputation based on regression was used to address cases of missing data. Several fit indices were evaluated to examine model fit, including chi-square and chi-square ratio (χ2/df), in which values below 5.0 are considered acceptable,37 the comparative fit index (CFI), in which values above .95 indicate good model fit,38 and the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), in which values below .06 or .08 indicate adequate fit38. Job tenure and nursing home size were included in the analyses as covariates. A p-value of .05 was used in all analyses.

Results

Table 2 presents direct effects and fit indices derived from the path analysis model. Inspection of model fit indices indicate a well-fitting model. Table 3 presents the indirect effects assessing communication and preparedness as separate mediating variables in the relationship between COVID-19-related stress and our two outcomes of interest: job satisfaction and intent to remain. Results demonstrate that direct care professionals working in larger nursing homes and those who have been employed longer at the nursing home are more likely to report intention to remain on the job.

Table 2.

Unstandardized and Standardized Path Coefficients and Model Fit.

| Path | B | S.E. | β | p | Χ2 | Χ2/df | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Fit Characteristics | 7.23 | 1.81 | .997 | .032 | ||||

| Stress → Preparedness (H1) | -.07 | .02 | -.08 | .003 | ||||

| Communication → Preparedness (H2) | .36 | .02 | .62 | <.001 | ||||

| Communication → Job Satisfaction (H2) | .20 | .02 | .43 | <.001 | ||||

| Preparedness → Job Satisfaction (H2) | .17 | .03 | .22 | <.001 | ||||

| Communication → Intent to Remain (H2) | .06 | .02 | .41 | .274 | ||||

| Preparedness → Intent to Remain (H2) | .02 | .02 | .11 | .246 | ||||

| Job Satisfaction → Intent to Remain (H3) | .29 | .06 | .96 | <.001 | ||||

| Stress → Job Satisfaction (H4) | -.04 | .02 | -.06 | .028 | ||||

| Stress → Intent to Remain (H4) | .02 | .02 | .12 | .195 | ||||

| Covariate: Job Tenure → Intent to Remain | .01 | .002 | -.01 | .828 | ||||

| Covariate: Facility Size → Intent to Remain | .01 | .001 | -.02 | .583 |

Note. CFI = Comparative Fit Index; df = degrees of freedom; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation.

Table 3.

Indirect Effects of Communication and Preparedness on Job Satisfaction and Intent to Remain.

| 95% CI |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path | Coefficient | SE | p | Lower | Upper |

| Stress → Communication → Preparedness (H1) | -.13 | .02 | <.001 | -.176 | -.089 |

| Stress → Communication → Job Satisfaction (H4) | -.07 | .01 | <.001 | -.100 | -.046 |

| Stress → Preparedness → Job Satisfaction (H4) | -.01 | .005 | .001 | -.023 | -.004 |

| Stress → Communication → Intent to Remain (H4) | -.02 | .02 | .279 | -.075 | .020 |

| Stress → Preparedness → Intent to Remain (H4) | -.002 | .002 | .264 | -.006 | .003 |

Note: CI = Confidence Interval.

Confirming hypothesis 1, results show that higher levels of COVID-19 related stress were significantly negatively associated with employee preparedness (β=-.08, p=.003). Inspection of 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals examining communication as a mediator indicate that the relationship between COVID-19 related stressors and job preparedness was significantly mediated by quality of communication, indicating that higher quality of communication mediated the negative impact of COVID-19 related stressors on preparedness (see Table 3 for indirect effect).

Partially confirming hypothesis 2, higher quality of employer communication was found to be directly associated with higher levels of preparedness (β=.36, p<.001) and job satisfaction (β=.17, p<.001), but was not significantly associated with intent to remain in one's position (β=.06, p=.274). Similarly, greater preparedness was also significantly associated with higher levels of job satisfaction (β=.17, p<.001), but the association between preparedness and intent to remain was not significant.

Confirming hypothesis 3, higher levels of job satisfaction were significantly associated with a higher likelihood of intent to remain in one's job (β=.29, p<.001).

Partially confirming Hypothesis 4, higher levels of COVID-19-related stress were significantly associated with lower levels of job satisfaction (β=-.04, p=.028), but not with intent to remain (p=.195). Further, the relationship between COVID-19-related stress and job satisfaction was significantly mediated by quality of communication, such that higher quality communication mediated the negative impact of COVID-19-related stress on job satisfaction (see Table 3 for indirect effect). However, communication did not significantly mediate the relationship between overall COVID-19 related stress on intent to remain.

The examination of preparedness as a mediator showed similar findings; preparedness significantly mediated the negative impact of COVID-19 stress and job satisfaction (see Table 3 for indirect effect). Conversely, no significant indirect effects were identified for preparedness as a mediator between COVID-19 related stress and intent to remain.

Discussion

The main purpose of this study was to identify modifiable factors associated with turnover intent in nursing home direct care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. The only factor directly associated with intent to remain was higher job satisfaction. There were no significant direct associations between intent to remain and COVID-19-related work stress, quality of communication, and preparedness. Rather, it seems that the relationship between these variables and intent to remain solely exists via the variable of job satisfaction. Study findings further show that during times of high work stress due to COVID-19 when employer communication is qualitatively high and perceived preparedness to provide care is high, direct care professionals still reported high job satisfaction which in turn was associated with intent to remain. The association between job satisfaction and turnover intent is in line with past research conducted during the pre-COVID-19 era.23 The study also confirmed that feelings of more optimal job competency – that is feelings of preparedness – were associated with better job satisfaction. However, a relationship between job competency and turnover intent as found in prior research28 could not be confirmed. This may indicate that preparedness is not an appropriate indicator of job competency. Further, study findings converge with prior research on the importance of quality of employer communication in job satisfaction of direct care professionals.30 , 31 In sum, study results point to job satisfaction as the one ingredient to reducing turnover intent and possibly actual turnover in direct care professionals. Better job satisfaction can be achieved through providing high quality of employer communication which results in better preparedness to care for residents. Study results point to the importance of employer communication and employee preparedness in enhancing job satisfaction and avoiding turnover particularly during times of high stress work experiences, such as a pandemic.

Study limitations

Several study limitations need to be acknowledged. First, our sample was a convenience sample of direct care professionals working at nursing homes that utilized WeCare ConnectTM as an employee management system and not a random sample of nursing home direct care professionals. Relatedly, nursing homes using an employee management system like WeCare ConnectTM are likely nursing homes committed to quality improvement and are therefore not representative of all nursing homes across the country in terms the communication and training they provided to their direct care professionals during the pandemic. Therefore, generalizability of study findings is limited to nursing homes that are using WeCareConnectTM. Further, WeCareConnectTM does not capture socio-demographic background information on employees. But these characteristics could be related to direct care professionals’ turnover intent. Finally, our study is cross-sectional in nature, and therefore, a causal relationship between variables cannot be established.

Conclusions and implications

During the COVID-19 pandemic the key factor influencing turnover intent in our sample of nursing home direct care professionals was their job satisfaction - the level of which was driven by how well the organization they worked for communicated with them and how well prepared they felt caring for residents during COVID-19. High quality communication is also essential for direct care professionals to feel competent to care for residents during the extremely stressful work time of the pandemic and can, in fact, mediate some of the job stress experienced. Therefore, nursing home leadership should not only train staff appropriately in resident care, but also ensure that supervisors have strong communication skills to provide clear and transparent communication to staff at all times, especially during periods of crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic. This communication should include information about the care of residents as well as information about the overall state of the organization. To keep direct care professionals in their jobs, employers could also provide supportive services which promote work-life balance and alleviate financial hardships. Employers could also enhance direct care professionals’ workplace autonomy by, for example, offering flexible shifts. In addition, employers could ensure paying living wages to direct care professionals and providing career lattices. Moving beyond COVID-19, there is a need to not only support current direct care professionals by providing the above described supports to avoid potential turnover, but there is also a need to strengthen the pipeline of direct care professionals. Increasing the number of direct care professionals could be accomplished by recruiting from nontraditional worker groups, such as high school students and individuals who want or need to work past retirement. In addition, there is a need to work with policymakers to explore immigration policies that could expand the direct care professional labor pool by increasing the number of foreign-born individuals who can work in the United States.

Funding

This work was supported by the Patrick and Catherine Weldon Donaghue Medical Research Foundation.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank David Gehm, president & CEO of Wellspring Lutheran Services and Jon Golm, president of WeCare ConnectTM and his team for their collaboration on this study.

References

- 1.PHI. PHI Workforce Data Center. 2021; Accessed from: https://phinational.org/policy-research/workforce-data-center/

- 2.Stone, R.I. & Bryant, N. Feeling valued because they are valued: A vision for professionalizing the caregiving workforce in the field of long-term services and supports. 2021; Washington, DC LeadingAge. https://leadingage.org/sites/default/files/Workforce%20Vision%20Paper_FINAL.pdf

- 3.Almeida B, Cohen MA, Stone RI, Weller CE. The demographics and economics of direct care staff highlight their vulnerabilities amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. J Aging Soc Policy. 2020;32(4-5):403–409. doi: 10.1080/08959420.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greene J, Gibson DM. Workers at long-term care facilities and their risk for severe COVID-19 illness. Prev Med. 2021;143 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gross CP, Essien UR, Pasha S, Gross JR, Wang SYI, Nunez-Smith M. Racial and ethnic disparities in population-level Covid-19 mortality. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(10):3097–3099. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06081-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cimarolli V.R., Bryant N.S., Falzarano F., Stone R. Job resignation in nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of quality of employer communication. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2022;41(1):12–21. doi: 10.1177/07334648211040509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White EM, Wetle TF, Reddy A, Baier RR. Front-line nursing home staff experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(1):199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ecker S, Pinto S, Sterling M, Wiggins F, Ma C. Working experience of certified nursing assistants in the greater New York City area during the COVID-19 pandemic: results from a survey Study. Geriatric Nursing. 2021;42(6):1556–1561. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2021.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirzinger A., Kearney A., Hamel L., Brodie M. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2020. KFF/The Washington Post Frontline Health Care Workers Survey. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tomlin J, Dalgleish-Warburton B, Lamph G. Psychosocial support for healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01960. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01960 Accessed May 24, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu AW, Buckle P, Haut ER, et al. Supporting the emotional well-being of health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Patient Saf Risk Manag. 2020;25(3):93–96. doi: 10.1177/2516043520931971. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abbasi J. Abandoned” nursing homes continue to face critical supply and staff shortages as COVID-19 toll has mounted. JAMA. 2020;324(2):123. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.10419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Health Care Association and National Center for Assisted Living. State of the long-term care industry: survey of nursing home and assisted living providers show industry facing significant workforce crisis. 2021; Retrieved from:https://www.ahcancal.org/News-and-Communications/Fact-Sheets/FactSheets/Workforce-Survey-September2021.pdf

- 14.Gandhi A, Yu H, Grabowski DC. High nursing staff turnover in nursing homes offers important quality information. Health Aff (Millwood) 2021;40(3):384–391. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.PIRG Education Fund. Nursing home safety during Covid: staff shortages. 2021; Report.

- 16.Xu H, Intrator O, Bowblis JR. Shortages of staff in nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic: what are the driving factors? J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(10):1371–1377. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGilton KS, Escrig-Pinol A, Gordon A, et al. Uncovering the devaluation of nursing home staff during COVID-19: are we fuelling the next health care crisis? J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(7):962–965. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castle NG. Nursing home caregiver staffing levels and quality of care: a literature review. J Appl Gerontol. 2008;27(4):375–405. doi: 10.1177/0733464808321596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Figueroa JF, Wadhera RK, Papanicolas I, et al. Association of nursing home ratings on health inspections, quality of care, and nurse staffing with COVID-19 cases. JAMA. 2020;324(11):1103–1105. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.14709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gorges RJ, Konetzka RT. Staffing levels and COVID-19 cases and outbreaks in U.S. nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(11):2462–2466. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bishop CE, Weinberg DB, Leutz W, Dossa A, Pfefferle SGM, Zincavage R. Nursing assistants’ job commitment: effect of nursing home organizational factors and impact on resident well-being. Gerontologist. 2008;48(1):36–45. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.Supplement_1.36. suppl. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trinkoff AM, Han K, Storr CL, Lerner N, Johantgen M, Gartrell K. Turnover, staffing, skill mix, and resident outcomes in a national sample of US nursing homes. J Nurs Adm. 2013;43(12):630–636. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Castle NG, Engberg J, Anderson R, Men A. Job satisfaction of nurse aides in nursing homes: intent to leave and turnover. Gerontologist. 2007;47(2):193–204. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vandenberg R, Nelson J. Disaggregating the motives underlying turnover intentions: when do intentions predict turnover behavior? Published online 1999. doi:10.1023/A:1016964515185

- 25.Chang YC, Yeh TF, Lai IJ, Yang CC. Job competency and intention to stay among nursing assistants: the mediating effects of intrinsic and extrinsic job satisfaction. IJERPH. 2021;18(12):6436. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18126436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choi J, Johantgen M. The importance of supervision in retention of CNAs. Res Nurs Health. 2012;35(2):187–199. doi: 10.1002/nur.21461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Decker FH, Harris-Kojetin LD, Bercovitz A. Intrinsic job satisfaction, overall satisfaction, and intention to leave the job among nursing assistants in nursing homes. Gerontologist. 2009;49(5):596–610. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zimmerman RD, Darnold TC. The impact of job performance on employee turnover intentions and the voluntary turnover process: a meta-analysis and path model. Personnel Rev. 2009;38(2):142–158. doi: 10.1108/00483480910931316. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vogelsmeier A, Scott-Cawiezell J. Achieving quality improvement in the nursing home: influence of nursing leadership on communication and teamwork. J Nurs Care Qual. 2011;26(3):236–242. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0b013e31820e15c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blanco-Donoso LM, Moreno-Jiménez J, Amutio A, Gallego-Alberto L, Moreno-Jiménez B, Stressors Garrosa E., Resources Job. Fear of contagion, and secondary traumatic stress among nursing home workers in face of the COVID-19: the case of Spain. J Appl Gerontol. 2021;40(3):244–256. doi: 10.1177/0733464820964153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.White EM, Wetle TF, Reddy A, Baier RR. Front-line nursing home staff experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(1):199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hayes AF. Guilford Publications; 2017. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis, Second Edition: A Regression-Based Approach. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee JK. The effects of social comparison orientation on psychological well-being in social networking sites: serial mediation of perceived social support and self-esteem. Curr Psychol. 2020;14 doi: 10.1007/s12144-020-01114-3. Published online October. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Preacher K, Hayes A. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008 doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879. Published online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu Y, Yang X, Wang S, et al. Serial multiple mediation of the association between internet gaming disorder and suicidal ideation by insomnia and depression in adolescents in Shanghai, China. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20:460. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02870-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao X, Lynch JG, Jr, Chen Q. Reconsidering baron and kenny: myths and truths about mediation analysis. J Consum Res. 2010;37(2):197–206. doi: 10.1086/651257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wheaton B, Muthén B, Alwin DF, Summers GF. Assessing reliability and stability in panel models. Sociol Methodol. 1977;8:84–136. doi: 10.2307/270754. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Eq Model: Multidiscipl J. November 3, 2009 doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. Published online. [DOI] [Google Scholar]