Abstract

The past decade has become an important strategy in precision medicine for the targeted therapy of many diseases, expecially various types of cancer. As a promising targeted element, nucleic acid aptamers are single-stranded functional oligonucleotides which have specific abilities to bind with various target molecules ranging from small molecules to entire organisms. They are often named ‘chemical antibody’ and have aroused extensive interest in diverse clinical studies on account of their advantages, such as considerable biostability, versatile chemical modification, low immunogenicity and quick tissue penetration. Thus, aptamer-embedded drug delivery systems offer an unprecedented opportunity in bioanalysis and biomedicine. In this short review, we endeavor to discuss the recent advances in aptamer-based targeted drug delivery platforms for cancer therapy. Some perspectives on the advantages, challenges and opportunities are also presented.

Keywords: aptamers, targeted drug delivery, cancer therapy, aptamer-drug conjugates (ApDCs), aptamer-based nanomaterial system

1 Introduction

Aptamers are a special class of DNA or RNA oligonucleotides that fold up into unique three-dimensional (3D) conformations for specifically recognizing cognate molecular targets (Miao et al., 2021). Aptamers are usually screened via an in vitro iterative method named Systematic Evolution of Ligands by EXponential Enrichment (SELEX) (Tan et al., 2013), which was independently discovered by two American groups in early 1990s (Ni et al., 2011). In recent years, various aptamers have been isolated for diverse types of target molecules (Table 1), including organic and inorganic molecules, peptides, proteins, nucleic acids, bacterium and even live cells, such as EpCAM aptamer binds to epithelial cell adhesion molecules (EpCAM) and aptamer sgc8 against protein tyrosine kinase-7 (PTK-7) (Ni et al., 2021). Compared with other targeted ligands, aptamers possess many excellent properties, including high chemical stability and binding affinity, versatile chemical modification, low or even non immunogenicity, small size and quick tissue penetration (Yang et al., 2022). These remarkable advantages make aptamers widely used in the field of cancer targeted therapy (Sun et al., 2022) and diagnosis (Zhang et al., 2020). This review will predominantly provide a brief overview of recent researches on aptamer-based targeted systems for cancer therapy. The future possibilities and challenges of aptamer guided drug delivery system will also be discussed.

TABLE 1.

Examples of therapeutic aptamers in clinical stages for cancer therapy.

| Molecular targets | Names of aptamer examples (Blank means no self-explanation) | Disease indication | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| HER2 | Herceptamers | Cancer | (Chi-hong et al., 2003; Thiel et al., 2012; Varmira et al., 2013; Varmira et al., 2014; Zhu et al., 2017) |

| EGFR | E07 | Cancer | (Esposito et al., 2011; Li et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2014a) |

| EpCAM | SYL3C, Ep1 | Cancer | (Song et al., 2013; Xiang et al., 2015) |

| VEGF | Pegaptanib (PEGylated), VEap121 | AMD, Cancer | Gragoudas et al. (2004) |

| Nucleolin | AS1411 | Cancer | (Ireson and Kelland, 2006; Bates et al., 2009; Li et al., 2017; Liang et al., 2017; Weng et al., 2018; Fu and Xiang, 2020; Vandghanooni et al., 2020; He et al., 2021) |

| PTK7 | sgc8 | Cancer | (Shangguan et al., 2008; Huang et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2014b; Yang et al., 2015b; Cao et al., 2017; Gong et al., 2020) |

| IGHM | Td05 | Cancer | (Mallikaratchy et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2015b) |

| αvβ3 integrin | Apt-αvβ3 | Cancer | Mi et al. (2005) |

| NF-κB | Y1, Y3 | Cancer | Lebruska and Maher, (1999) |

| E2F3 transcription factor | aptamer 8–2 | Cancer | (Ishizaki et al., 1996; Martell et al., 2002) |

| HER3 | A30 | Cancer | Chen et al. (2003) |

| CD30 | C2, NGS6.0 | Cancer | Zhang et al. (2009) |

| CTLA-4 | CTLA4apt, aptCTLA-4 | Cancer | (Herrmann et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2017) |

| OX40 | 9C7, 11F11, 9D9 | Immune diseases, including Cancer | (Pratico et al., 2013; Soldevilla et al., 2015) |

| PD-1 | MP7 | Immune diseases, including Cancer | Prodeus et al. (2015) |

| PD-L1 | aptPD-L1 | Immune diseases, including Cancer | Lai et al. (2016) |

| Tim-3 | TIM3Apt | Immune diseases, including Cancer | Gefen et al. (2017) |

| LAG3 | Apt1, Apt2, Apt4, Apt5 | Immune diseases, including Cancer | Soldevilla et al. (2017) |

| CD28 | AptCD28 | Immune diseases, including Cancer | Lozano et al. (2016) |

| DEC205 | Immune diseases, including Cancer | Wengerter et al. (2014) | |

| IL-4Ra | cl.42 | Immune diseases, including Cancer | Liu et al. (2017) |

| IL-6R | AIR-3 | Immune diseases, including Cancer | Kruspe et al. (2014) |

| PLK1, BLC2 | Cancer | McNamara et al. (2006) | |

| Mucin-1, BCL2 | Cancer | Jeong et al. (2017) | |

| polynucleotide | Cancer | Nooranian et al. (2021) | |

| Mucin1 | AptA, AptB, S2.2 | Cancer | (Elghanian et al., 1997; Ferreira et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2014b; Hu et al., 2014) |

| OS cell | LC09 | Cancer | Zhao et al. (2019) |

| Adenosine | Cancer | Li et al. (2018a) | |

| ALPL protein | Apt19S | Cancer | Xuan et al. (2020) |

| PSMA | A9, A10 | Cancer | Lupold et al. (2002) |

HER: human epidermal growth factor receptor. EGFR: epidermal growth factor receptor. AMD: age-related macular degeneration. EpCAM: epithelial cell adhesion molecule. VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor. PSMA: prostate-specific membrane antigen. PTK7: protein tyrosine kinase 7. IGHM: immunoglobulin μ heavy chains. CTLA-4: cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4. PD-1: programmed death receptor I. PD-L1: programmed death ligand I. Tim-3: T cell immunoglobulin-3. LAG3: lymphocyte-activation gene 3. IL-6R: interleukin 6 receptor. PLK1: polo-like kinase 1. BLC2: B-cell lymphoma.

2 Aptamers as therapeutic agents

Aptamers, as therapeutic agents, can effectively recognize various proteins on the cell membrane or in the blood circulation to modulate their interaction with receptors and affect the corresponding biological pathways for the treatment of various diseases (Zhou and Rossi, 2017). The ongoing progresses in biomedical technology are encouraging the development of aptamers as therapeutic agents for improving human health. Over the past few decades, the number of therapeutic aptamers in clinical stages has been increasing (Nimjee1 et al., 2017). In 2004, Pegaptanib (Macugen), as the first aptamer in clinical use, was approved by the FDA to treat Age-related macular degeneration (AMD), which was known to the leading reason of blindness in many aging people (Ng et al., 2006). Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) can increase vascular permeability and induce angiogenesis, leading to AMD (Ucuzian et al., 2010). Pegaptanib as an anti-VEGF antagonist aptamer can specifically block VEGF and interfere with the interaction of VEGF and its receptors to treat AMD. For increasing its in vivo biostability, 40 kDa monomethoxypolyethylene glycol (PEG) was then conjugated with pegatanib to decrease nuclease degradation. However, the antibody fragment ranibizumab (Lucentis; Genentech) has recently occupied significant market due to blocking all types of human VEGF even and the smallest VEGF121 (Martin et al., 2011).

Another famous therapeutic aptamer AS1411 has been in clinical phase II trial for the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. AS1411 composed of thymine and guanines can form special guanine-mediated quadraplex structures in solution (Ireson and Kelland, 2006). Due to this unique three-dimensional (3D) structures, AS1411 can target to nucleolin protein with high specificity, which was normally found overexpressing on the surface of cancer cells. Unlike other aptamers, AS1411 was discovered by screening antisense oligonucleotides for antiproliferation effect (Bates et al., 1999). Although the underlying mechanisms of AS1411-based antiproliferation effect have not been fully comprehended, it has showed growth-antitumor abilities against a widely range of tumor cells through multiple signaling pathways involving BCL-2 mRNA destabilization and NF-κB inhibition (Soundararajan et al., 2008). Some studies have proved that guanine deaminase is an important pathway in affecting the cell-type selectivity to the anti-proliferation function of guanine-based biomolecules (Wang et al., 2019). So this rich guanine aptamer, as one of the most promising aptamers, has great hope to be used in clinical cancer therapy owing to its outstanding safety profile and anticancer ability in some intractable tumors (Zhang et al., 2015). In addition, there were some studies about AS1411 derivatives which were obtained by chemical modification with alternative nucleobases or backbones for improving chemical and biological properties. In 2016, Fan et al. reported the first AS1411 derivative that showed excellent ability in the inhibition of DNA replication and tumor cell growth, and induced S-phase cell cycle arrest via chemical modification of 2′-deoxyinosine in AS1411 aptamer (Cai et al., 2014). Subsequently, they also developed another strategy to modify AS1411 aptamer through the use of 2′-deoxyinosine (2′-dI) and D-/l-isothymidine (D-/L-isoT) for improving the bioactivity of AS1411 aptamer (Fan, Sun, Wu, Zhang, Yang). In addition to exploring aptamers for directly inhibiting cancer cells growth, aptamers can also indirectly display anticancer abilities through modulating the immune system. In recent years, some agonistic aptamers with immunomodulatory properties have been found. It is worth noting that these aptamers recognizing 4-1BB or OX40 almost show similar or even superior immunomodulatory ability to the corresponding antibodies, followed with similar anticancer effects. Examples of this type of aptamers include multimeric aptamers that can target 4-1BB (CD137) on activated T cells and improve T cell proliferation, IL-2 secretion, survival and cytolytic activity of T cells (McNamara et al., 2008).

3 Aptamer-drug conjugates for targeted drug delivery

In addition to being therapeutic agents, aptamers have been more widely explored as targeting carriers for the therapeutic agents delivery, such as chemotherapeutics, small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), microRNAs (miRNAs), toxins and so on (Xuan et al., 2018). Traditional ApDCs are mostly comprised of aptamers attached to various potent drugs through all kinds of cleavable or non-cleavable linkers. Compared with antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), a few of which have been applied to clinical treatment of cancer, ApDCs show many significant advantages, including relatively small size, synthesis procedure economy, chemical modification simplicity and tissue penetration speedy (Chen et al., 2017). Based on diseased-related biomarkers, ApDCs have been developed for a wide range of therapeutic modalities, such as chemotherapy, immunotherapy and so on.

Chemotherapy is one of the most fashional therapeutic modalities for cancer, but this conventional strategy suffers from serious drug toxicity in healthy tissues and various side effects. For improving therapeutic efficacy and diminishing side effects, ApDC-mediated targeted drug delivery has been studied. As an example, Tan et al. designed and synthesized a sgc8-Dox conjugate for targeted delivery of doxorubicin (Dox) (Huang et al., 2009). In this ApDCs, antitumor agent Dox was conjugated with aptamer sgc8 at a 1:1 ratio via an acid-labile hydrazone linker, such that Dox can be selectively delivered in acidic tumor environment. Zhang et al. reported a water-soluble nucleolin aptamer-paclitaxel conjugate that can specifically release PTX to the tumor site via a cathepsin B-labile valine-citrulline dipeptide linker (Li et al., 2017). Recently, a nucleolin aptamer (AS1411) loaded with BET-targeting PROTAC against breast cancer stem cells was reported by Sheng et al (He et al., 2021). Notably, the aptamer/drug ratio is essential in achieving excellent therapeutic efficacy. For maximizing drug delivery efficiency, a phosphoramidite prodrug of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) was developed and the resulting ApDCs with multiple drug copies can be synthesized via automated nucleic acid synthesis using standard solid-phase DNA synthesis chemistry (Wang et al., 2014b). In order to control drug release, a photocleavable linker was added to the bone of phosphoramidite prodrug. As a result, the ApDCs not only were efficiently internalized into cancer cells, but also showed specific drug release in a photocontrollable manner.

Besides conjugating with chemotherapeutic drugs, aptamer can also link with therapeutic RNA or DNA. In recent years, gene therapy as a hot therapeutic modality has made great breakthrough in the treatment of cancer (Song et al., 2021). However, just like many other therapeutic drugs, most of gene therapy agents lack specific recognition ability for the disease tissues, which make it vital to specifically deliver gene therapy agents to cancer cells. As target ligands, aptamers can be utilized to improve the gene therapy safety and therapeutic efficacy (Li et al., 2013). In an early research, an ApDCs was constructed using a PSMA-targeting aptamer and a small interfering RNA (siRNA), which can silence polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) and B-cell lymphoma 2 (BLC2) overexpressed in most human tumor cells (McNamara et al., 2006). In this study, the resulting ApDCs can not only specifically release siRNA into PSMA-positive LNCaP cells and lead to cell apoptosis, but also remarkably inhibit tumor growth in LNCaP tumor-bearing mices. Subsequently, Aptamer-siRNA conjugates have been systematically studied by PEGlation to optimize circulation half-life in the blood, by chemical modification to increase biostability, and by exploring the two-dimensional structure to improve the intracellular processing of RNA-induced genes silencing. In another research, a multiple mucin-1 aptamer was conjugated with BCL2-specific siRNA, and doxorubicin (Dox) was loaded into these conjugates through intercalation with nucleic acids (Jeong et al., 2017). These Dox-incorporated multivalent Apt-siRNA conjugates can overcome multidrug resistance into MDR cancer cells through aptamer-mediated codelivery of Dox and siRNA. Note that the 3D structure of multivalent Dox-Apt-siRNA were well defined, which is beneficial for their clinical application. Furthermore, aptamers were also successfully conjugated with other nucleic acid gene therapeutics, such as small hairpin RNA (shRNA) and microRNA (miRNA) (Soldevilla et al., 2018).

4 Aptamer-based nanomaterial system for targeted drug delivery

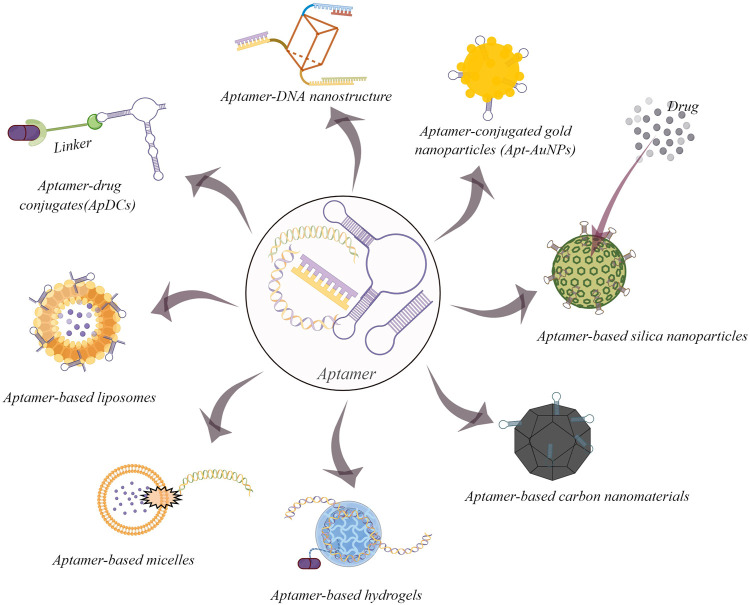

Nanomaterials play a crucial role in the application of bioanalysis and biomedicine (Li et al., 2021). Due to their unique physicochemical properties, including an ultra-small size, a large surface area and loading ability, nanomaterials have overcome many limitations of conventional therapeutic and diagnostic strategies (Dong et al., 2020). The key of nanomedicine development is to improve the specific recognition ability for disease tissues (Liu et al., 2021). The combination of aptamers and nanomaterials is a promising progress for targeted drug delivery (Figure 1) (Mahmoudpoura et al., 2021). In this section, several representative aptamer-based inorganic and organic nanomaterials on cancer therapy would be discussed.

FIGURE 1.

Some common examples of aptamer-based drug delivery systems for cancer therapy (By figdraw).

4.1 Aptamer-based inorganic nanomaterial systems

As an important inorganic nanomaterial, gold nanoparticles have gained considerable attentions in biomedicine as result of their high surface-to-volume ratio, low-toxicity, excellent stability and biological compatibility (Yang et al., 2015a). Aptamer-conjugated gold nanomaterials (Apt-AuNPs), which synergically possess special advantageous properties of aptamers and gold nanoparticles, have been widely utilized in the field of cancer diagnosis and therapy (Nooranian et al., 2021). A classical research from the Mirkin group employed target DNA molecules to form a polymeric network of nanoparticles for specifically detecting polynucleotide (Elghanian et al., 1997). Subsequently, there are emerging many corresponding studies, such as enzyme responsive Apt-AuNPs for mucin 1 protein (MUC1) detection (Hu et al., 2014), Apt-AuNPs combined with graphene oxide for the photothermal therapy of breast cancer (Yang et al., 2015b) and aptamer-functionalized AuNPs-Fe3O4-GS capture probe for monitoring circulating tumor cell in whole blood (Dou et al., 2019).

Among the set of inorganic nanomedicine, silica nanoparticles have become suitable carriers in drug delivery systems (Zou et al., 2020). These particles successfully provided controllable drug release in vivo and in vitro through the change in PH and temperature, photochemical reactions and certain redox reactions (Fu and Xiang, 2020). After combined with targeted elements such as aptamers, they can enhance cancer therapeutic effects with a lower dose of drug (Vandghanooni et al., 2020). As an early example, Cai’s group reported a novel Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles (MSN)-based redox-responsive nanocontainer for triplex cancer targeted therapy. In their study, AS1411 aptamer was tailored onto the CytC-sealed MSNs (Zhang et al., 2014a). And this system can lead to the special release of Dox into the tumor cells via the breakage of S-S bonds. In 2021, Tan et al. first developed FRET-based two-photon MSNs for multiplexed intracellular imaging and targeted drug delivery (Wu et al., 2021). The MSNs can display different two-photon multicolor fluoresence by varying the doping ratio of the three dyes. Furthermore, the Dox-loaded and aptamer-capped nanosystem can be efficiently internalized into the cancer cells and release the anticancer drug Dox. In addition, aptamer-targeted MSNs have also been widely used for gene targeted delivery, which can protect gene therapy agents from degradation by nuclease (Zhang et al., 2014b).

Conventional carbon nanomaterials, including fullerene, graphene, carbon dots/nanobots/nanotubes and hybrids, exhibit unique advantages in biomedical application (Weng et al., 2018). Aptamer-functionalized carbon nanomaterials make their ideal nanoplatforms for cancer diagnostics and therapeutics (Yang et al., 2018). Recently, Wang et al. developed the multifunctional, which showed heat-stimulative and sustained release properties (Wang et al., 2015). With the introduction of MUC1 aptamers, this nanoparticle can detect targeted MCF-7 breast cells with excellent recognition ability. In addition, aptamer-based graphene nanomaterials have gained many fascinating developments in cancer gene therapy. In 2017, aptamer-based graphene quantum dots loaded with porphyrin derivatives photosensitizer were reported for fluorescence-guided photothermal/photodynamic synergetic therapy (Cao et al., 2017). This multifunctional theranostic nanomaterials displayed good feasibility for detecting intracellular cancer-related miRNA, whereas the intrinsic fluorescence could be used to distinguish cancer cells from somatic cells.

4.2 Aptamer-based organic nanomaterial systems

As the first explored drug delivery system, liposomes have many promising properties such as good biocompatibility, low toxicity, low immunogencity and excellent drug loading efficiency (Moosaviana and Sahebkar, 2019). PEGylated liposomal doxorubicin, Doxil®, is the first FDA-approved liposomal drug for the treatment of solid tumors. With the rapid development of biotechnology, liposomal systems with specific targeting ability have been synthesized successfully by the introduction of various molecular recognition elements, such as folate, peptides, antibodies, and aptamers. Among them, aptamer-based lipsomes have attracted widely attention (Zhao et al., 2019). In the early research, Tan et al. reported a therapeutic aptamer-modified liposome nanoparticle with dual-fluorophore labeling for targeted drug delivery (Kang et al., 2010). This system was conjugated with a sgc8 aptamer that showed high binding and internalization ability for targeted CEM cells. The flow cytometry and confocal imaging experiments showed sgc8-modified liposomes could deliver loaded drug to targeted cancer cells with high specificity and excellent efficiency. In recent attempts, the CRISPR/Cas9 complex were packaged into aptamer-functionalized liposomes for specific cancer gene therapy (Gong et al., 2020). For example, Liang et al. developed an aptamer-based lipopolymer for tumor-specific delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 to regulate VEGFA in osteosarcoma (Liang et al., 2017). In this system, LC09 aptamer could facilitate the selective distribution of CRISPR/Cas9 plasmids to decrease VEGFA expression, leading to inhibite orthotopic osteosarcoma malignancy and lung metastasis.

Another promising type of aptamer-based organic nanomaterial is the micelle structure. This drug delivery system displays excellent binding ability of aptamers to target due to the multivalent effect. Thus, it can be developed for numerous bioapplications (Wu et al., 2010). In 2018, Li et al. developed a cross-linked aptamer-lipid micelle system for excellent stability and specificity in target-cell recognition (Li et al., 2018a). In this facile approach, aptamer and lipid segments were linked to a methacrylamide branch via an efficient photoinduced polymerization process. In contrast to traditional aptamer-lipid micelles, this reported system provided better biostability in a cellular environment, further improving the targeting ability for imaging applications. In another fashion study, a novel aptamer-prodrug conjugate micelle was prepared by combining hydrophobic prodrug bases and bioorthogonal chemistry for hydrogen peroxide and pH-independent cancer chemodynamic therapy (Xuan et al., 2020). In depth mechanistic work reveal that, this system could be activated by intracellular Fe2+ to generate toxic C-centered free radicals self-circularly via cascading bioorthogonal reactions.

Among aptamer-based organic nanomaterial systems, target-responsive DNA hydrogels exhibited superior mechanical properties and programmable features and were widely used in biomedical and pharmaceutical applications (Li et al., 2016). In 2008, the first adenosine-responsive hydrogel was developed for potential drug release. In this work, two oligonucleotide-incorporated polyacrylamide and rationally designed cross-linking oligonucleotides were used to form the DNA nanohydrogels. The DNA linker contained the aptamer sequence for adenosine. When existing adenosine molecules, the aptamer will bind to target molecules, resulting in the breakdown of the cross-links and the dissolution of the hydrogel. Thus, this system could be explored for target-responsive drug release (Yang et al., 2008). In other elegant example, Yao et al. reported a physically cross-linked DNA network to fish bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) from numerous nontarget cells (Yao et al., 2020). This nanomaterial containing a Apt19S aptamer sequence provided a 3D microenvironment to maintain excellent activity of captured stem cells.

In addition, due to the principle of complementary base pairing, aptamers can be easily integrated to prepare various DNA nanostructures for specific cancer cell recognition and subsequent applications (Seeman and Sleiman, 2018). As an important DNA-based nanostructures, DNA origami have been modified with various small molecule drugs, functional NA sequences, and nanomaterials (Bolaños Quiñones et al., 2018). In 2018, a smart DNA nanorobot was reported by Li’s group for intelligent drug delivery in cancer therapy. Because of functionalizing on the outside with aptamer AS1411, this DNA nanorobot can specifaically deliver thrombin to tumor-associated blood vessels for inhibiting the tumor growth (Li et al., 2018b). Subsquently, the aptamer-functionalized DNA Origami, named Apt-Dox-orgami-ASO, was developed by Pan’s group to co-deliver Dox and antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) in cancer cells. This multifunctional DNA origami-based nanocarrier was precisely synthesized to adsorb Dox and load Bcl2 and P-gp ASOs for the efficient therapy of drug-resistant cancer (Pan et al., 2020). As cargo carriers, all kinds of aptamer-based DNA nanostructures have been explored By molecular engineering for targeted drug delivery in cancer therapy (Hu et al., 2018).

5 Conclusion

In the past decades, the achieved developments proved that aptamers had broad potential in the research field of cancer therapy. Multiple unique properties of aptamers attracted considerable attention in the development of aptamers as nucleic acids-functionalized alternatives to folic acid, peptides and antibodies for targeted drug delivery. This short review summarizes some recent advances of aptamer-based systems in cancer therapy. In fact, the exploration of aptamers and aptamer-drug conjugates is still in a relatively early stage. Considerable efforts should be made to overcome their bottlenecks in the clinical application. In addition, the most remarkable achievements of aptamers involved their combination with nanomaterials, enhancing the specificity of the diagnostic signal and leading to excellent target cancer cell recognition and delivery. In summary, the above description showed the versatility and therapeutic applicability of aptamers. However, multiple challenges, including poor biostability, short half-lives in vivo and unclear mechanism of endosomal escape and drug release, need to be overcome before moving forward to clinical application. Furthermore, more systematic research on organ toxicity, the safety on genomics and proteomics, the large-scale production technology and costs need to be further investigated. Despite these limitations, the rapid development of chemistry and materials encourages us to explore aptamer-based drug delivery systems with high therapeutic effects.

Author contributions

FG, JY and YC contributed equally. FG contributed to the conception. JY and YC drew the figures and wrote the article. CG revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (No. 21ZR1422600) and China NSFC (Nos. 2210070260).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor RW declared a past co-authorship with the author FG.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Bates P. J., Kahlon J. B., Thomas S. D., Trent J. O., Miller D. M. (1999). Antiproliferative activity of G-rich oligonucleotides correlates with protein binding. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 26369–26377. 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates P. J., Laber D. A., Miller D. M., Thomas S. D., Trent J. O. (2009). Discovery and development of the G-rich oligonucleotide AS1411 as a novel treatment for cancer. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 86, 151–164. 10.1016/j.yexmp.2009.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolaños Quiñones V. A., Zhu H., Solovev A. A., Mei Y., Gracias D. H. (2018). Origami biosystems: 3D assembly methods for biomedical applications. Adv. Biosyst. 2, 201800230. 10.1002/adbi.201800230 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cai B., Yang X., Sun L., Fan X., Li L., Jin H., et al. (2014). Stability and bioactivity of thrombin binding aptamers modified with D-/L-isothymidine in the loop regions. Org. Biomol. Chem. 12, 8866–8876. 10.1039/C4OB01525H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y., Dong H., Yang Z., Zhong X., Chen Y., Dai W., et al. (2017). Aptamer-conjugated graphene quantum dots/porphyrin derivative theranostic agent for intracellular cancer-related MicroRNA detection and fluorescence-guided photothermal/photodynamic synergetic therapy. ACS Appl. Mat. Interfaces 9, 159–166. 10.1021/acsami.6b13150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C.-h. B., Chernis G. A., Hoang V. Q., Landgraf R. (2003). Inhibition of heregulin signaling by an aptamer that preferentially binds to the oligomeric form of human epidermal growth factor receptor-3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100, 9226–9231. 10.1073/pnas.1332660100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K., Liu B., Yu B., Zhong W., Lu Y., Zhang J. N., et al. (2017). Advances in the development of aptamer drug conjugates for targeted drug delivery. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 9, e1438. 10.1002/wnan.1438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi-hong B. C., George A. C., Van Q. H., Ralf L. (2003). Inhibition of heregulin signaling by an aptamer that preferentially binds to the oligomeric form of human epidermal growth factor receptor-3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100, 9226–9231. 10.1073/pnas.1332660100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y., Yao C., Zhu Y., Yang L., Luo D., Yang D., et al. (2020). DNA functional materials assembled from branched DNA: Design, synthesis, and applications. Chem. Rev. 120, 9420–9481. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou B., Xu L., Jiang B., Yuan R., Xiang Y. (2019). Aptamer-functionalized and gold nanoparticle array-decorated magnetic graphene nanosheets enable multiplexed and sensitive electrochemical detection of rare circulating tumor cells in whole blood. Anal. Chem. 91, 10792–10799. 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b02403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elghanian R., Storhoff J. J., Mucic R. C., Letsinger R. L., Mirkin C. (1997). Selective colorimetric detection of polynucleotides based on the distance-dependent optical properties of gold nanoparticles. Science 277, 1078–1081. 10.1126/science.277.5329.1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito C. L., Passaro D., Longobardo I., Condorelli G., Marotta P., Affuso A., et al. (2011). A neutralizing RNA aptamer against EGFR causes selective apoptotic cell death. PLoS One 6, e24071. 10.1371/journal.pone.0024071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan X., Sun L., Wu Y., Zhang L., Yang Z. (2016). Bioactivity of 2′- deoxyinosineincorporated aptamer AS1411. Sci. Rep. 6, 25799. 10.1038/srep25799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira C. S., Matthews C. S., Missailidi S. (2006). DNA aptamers that bind to MUC1 tumour marker: Design and characterization of MUC1-binding single-stranded DNA aptamers. Tumor Biol. 27, 289–301. 10.1159/000096085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Z., Xiang J. (2020). Aptamer-functionalized nanoparticles in targeted delivery and cancer therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 9123. 10.3390/ijms21239123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gefen T., Castro I., Muharemagic D., Puplampu-Dove Y., Patel S., Gilboa E., et al. (2017). A TIM-3 oligonucleotide aptamer enhances T cell functions and potentiates tumor immunity in mice. Mol. Ther. 25, 2280–2288. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.06.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y., Tian S., Xuan Y., Zhang S. (2020). Lipid and polymer mediated CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing. J. Mat. Chem. B 8, 4369–4386. 10.1039/D0TB00207K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gragoudas E. S., Adamis A. P., Cunningham E. T., Feinsod M., Guyer D. R. (2004). Pegaptanib for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N. Engl. J. Med. 351, 2805–2816. 10.1056/nejmoa042760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S., Gao F., Ma J., Ma H., Dong G., Sheng C., et al. (2021). Aptamer-PROTAC conjugates (APCs) for tumor-specific targeting in breast cancer. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 23299–23305. 10.1002/anie.202107347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann A., Priceman S. J., Swiderski P., Kujawski M., Xin H., Zhang W., et al. (2014). CTLA4 aptamer delivers STAT3 siRNA to tumor-associated and malignant T cells. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 2977–2987. 10.1172/JCI73174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Q., Wang S., Wang L., Gu H., Fan C. (2018). DNA nanostructure-based systems for intelligent delivery of therapeutic oligonucleotides. Adv. Healthc. Mat. 7, 1701153. 10.1002/adhm.201701153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu R., Wen W., Wang Q., Xiong H., Zhang X., Gu H., et al. (2014). Novel electrochemical aptamer biosensor based on an enzyme-gold nanoparticle dual label for the ultrasensitive detection of epithelial tumour marker MUC1. Biosens. Bioelectron. X. 53, 384–389. 10.1016/j.bios.2013.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B. T., Lai W. Y., Chang Y. C., Wang J. W., Yeh S. D., Lin E. P. Y., et al. (2017). A CTLA-4 antagonizing DNA aptamer with antitumor effect. Mol. Ther. - Nucleic Acids 8, 520–528. 10.1016/j.omtn.2017.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.-F., Shangguan D., Liu H., Phillips J. A., Zhang X., Chen Y., et al. (2009). Molecular assembly of an aptamer–drug conjugate for targeted drug delivery to tumor cells. ChemBioChem 10, 862–868. 10.1002/cbic.200800805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ireson C. R., Kelland L. R. (2006). Discovery and development of anticancer aptamers. Mol. Cancer Ther. 5, 2957–2962. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizaki J., Nevins J. R., Sullenger B. A. (1996). Inhibition of cell proliferation by an RNA ligand that selectively blocks E2F function. Nat. Med. 2, 1386–1389. 10.1038/nm1296-1386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong H., Lee S. H., Hwang Y., Yoo H., Juang H., Kim S. H., et al. (2017). Multivalent aptamer–RNA conjugates for simple and efficient delivery of doxorubicin/siRNA into multidrug-resistant cells. Macromol. Biosci. 17, 1600343. 10.1002/mabi.201600343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H., O’Donoghue M. B., Liu H., Tan W. (2010). A liposome-based nanostructure for aptamer directed delivery. Chem. Commun. 46, 249–251. 10.1039/b916911c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruspe S., Meyer C., Hahn U. (2014). Chlorin e6 Conjugated Interleukin-6 Receptor Aptamers Selectively Kill Target Cells upon Irradiation. Mol. Ther. - Nucleic Acids 3, e143. 10.1038/mtna.2013.70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai W. Y., Huang B. T., Wang J. W., Lin P. Y., Yang P. C. (2016). A novel PD-L1-targeting antagonistic DNA aptamer with antitumor effects. Mol. Ther. - Nucleic Acids 5, e397. 10.1038/mtna.2016.102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebruska L. L., Maher L. J. (1999). Selection and characterization of an RNA decoy for transcription factor NF-κB. Biochemistry 38, 3168–3174. 10.1021/bi982515x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F., Lu J., Liu J., Liang C., Wang M., Wang L., et al. (2017). A water-soluble nucleolin aptamer-paclitaxel conjugate for tumor-specific targeting in ovarian cancer. Nat. Commun. 8, 1390. 10.1038/s41467-017-01565-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Mo L., Lu C.-H., Fu T., Yang H.-H., Tan W., et al. (2016). Functional nucleic acid-based hydrogels for bioanalytical and biomedical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 1410–1431. 10.1039/c5cs00586h [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N., Nguyen H. H., Byrom M., Ellington A. D. (2011). Inhibition of cell proliferation by an anti-EGFR aptamer. PLoS One 6, e20299. 10.1371/journal.pone.0020299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Jiang Q., Liu S., Zhang Y., Tian Y., Song C., et al. (2018). A DNA nanorobot functions as a cancer therapeutic in response to a molecular trigger in vivo . Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 258–264. 10.1038/nbt.4071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S. L., Jiang P., Jiang F. L., Liu Y. (2021). Recent advances in nanomaterial-based nanoplatforms for chemodynamic cancer therapy. Adv. Funct. Mat. 31, 2100243. 10.1002/adfm.202100243 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Figg C. A., Wang R., Jiang Y., Lyu Y., Sun H., et al. (2018). Cross-linked aptamer–lipid micelles for excellent stability and specificity in target-cell recognition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 130, 11589–11593. 10.1002/anie.201804682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Zhao Q., Qiu L. (2013). Smart ligand: Aptamer-mediated targeted delivery of chemotherapeutic drugs and siRNA for cancer therapy. J. Control. Release 171, 152–162. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang C., Li F., Wang L., Zhang Z.-K., Wang C., He B., et al. (2017). Tumor cell-targeted delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 by aptamer-functionalized lipopolymer for therapeutic genome editing of VEGFA in osteosarcoma. Biomaterials 147, 68–85. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Zhang Q., Wang S., Weng W., Jing Y., Su J., et al. (2021). Bacterial extracellular vesicles as bioactive nanocarriers for drug delivery: Advances and perspectives. Bioact. Mat. 14, 169–181. 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2021.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. J., Dou X. Q., Wang F., Zhang J., Wang X. L., Xu G. L., et al. (2017). IL-4Rα aptamer-liposome-CpG oligodeoxynucleotides suppress tumour growth by targeting the tumour microenvironment. J. Drug Target. 25, 275–283. 10.1080/1061186X.2016.1258569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano T., Soldevilla M. M., Casares N., Villanueva H., Bendandi M., Lasarte J. J., et al. (2016). Targeting inhibition of foxp3 by a CD28 2'-fluro oligonucleotide aptamer conjugated to P60-peptide enhances active cancer immunotherapy. Biomaterials 91, 73–80. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupold S. E., Hicke B. J., Lin Y., Coffey D. S. (2002). Identification and characterization of nuclease-stabilized RNA molecules that bind human prostate cancer cells via the prostate-specific membrane antigen. Cancer Res. 62, 4029–4033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudpoura M., Dingd S., Lyud Z., Ebrahimie G., Dud D., Dolatabadif J. E. N., et al. (2021). Aptamer functionalized nanomaterials for biomedical applications: Recent advances and new horizons. Nano Today 39, 101177. 10.1016/j.nantod.2021.101177 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mallikaratchy P., Tang Z., Kwame S., Meng L., Shangguan D., Tan W., et al. (2007). Aptamer directly evolved from live cells recognizes membrane bound immunoglobin heavy mu chain in burkitt's lymphoma cells. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 6, 2230–2238. 10.1074/mcp.M700026-MCP200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martell R. E., Nevins J. R., Sullenger B. A. (2002). Optimizing aptamer activity for gene therapy applications using expression cassette SELEX. Mol. Ther. 6, 30–34. 10.1006/mthe.2002.0624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin D. F., Maguire M. G., Ying G. s., Grunwald J. E., Fine S. L., Jaffe G. J. (2011). Ranibizumab and bevacizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 1897–1908. 10.1056/NEJMoa1102673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara J. O., Andrechek E. R., Wang Y., Viles K. D., Rempel R. E., Gilboa E., et al. (2006). Cell type–specific delivery of siRNAs with aptamer-siRNA chimeras. Nat. Biotechnol. 24, 1005–1015. 10.1038/nbt1223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara J. O., Kolonias D., Pastor F., Mittler R. S., Chen L., Giangrande P. H., et al. (2008). Multivalent 4-1BB binding aptamers costimulate CD8+ T cells and inhibit tumor growth in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 376–386. 10.1172/JCI33365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi J., Zhang X., Giangrande P. H., McNamara J. O., Nimjee S. M., Sarraf-Yazdi S., et al. (2005). Targeted inhibition of αvβ3 integrin with an RNA aptamer impairs endothelial cell growth and survival. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 338, 956–963. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.10.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao Y., Gao Q., Mao M., Zhang C., Yang L., Yang Y., et al. (2021). Bispecific aptamer chimeras enable targeted protein degradation on cell membranes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 11267–11271. 10.1002/anie.202102170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moosaviana S. A., Sahebkar A. (2019). Aptamer-functionalized liposomes for targeted cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 448, 144–154. 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.01.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng E. W. M., Shima D. T., Calias P., Cunningham E. T., Guyer D. R., Adamis A. P., et al. (2006). Pegaptanib, a targeted anti-VEGF aptamer for ocular vascular disease. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 5, 123–132. 10.1038/nrd1955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni S., Zhuo Z., Pan Y., Yu Y., Li F., Liu J., et al. (2021). Recent progress in aptamer discoveries and modifications for therapeutic applications. ACS Appl. Mat. Interfaces 13, 9500–9519. 10.1021/acsami.0c05750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni X., Castanares M., Mukherjee A., Lupold S. E. (2011). Nucleic acid aptamers: Clinical applications and promising new horizons. Curr. Med. Chem. 18, 4206–4214. 10.2174/092986711797189600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimjee1 S. M., White R. R., Becker R. C., Sullenger B. A. (2017). Aptamers as therapeutics. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 57, 61–79. 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010716-104558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nooranian S., Mohammadinejad A., Mohajeri T., Aleyaghoob G., Oskuee R. K. (2021). Biosensors based on aptamer-conjugated gold nanoparticles: A review. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem., 1–18. 10.1002/bab.2224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Q., Nie C., Hu Y., Yi J., Liu C., Zhang J., et al. (2020). Aptamer-functionalized DNA origami for targeted codelivery of antisense oligonucleotides and doxorubicin to enhance therapy in drug-resistant cancer cells. ACS Appl. Mat. Interfaces 12, 400–409. 10.1021/acsami.9b20707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratico E. D., Sullenger B. A., Nair S. K. (2013). Identification and characterization of an agonistic aptamer against the T cell costimulatory receptor, OX40. Nucleic Acid. Ther. 23, 35–43. 10.1089/nat.2012.0388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prodeus A., Abdul-Wahid A., Fischer N. W., Huang E. H., Cydzik M., Gariepy J., et al. (2015). Targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 immune evasion Axis with DNA aptamers as a novel therapeutic strategy for the treatment of disseminated cancers. Mol. Ther. - Nucleic Acids 4, e237. 10.1038/mtna.2015.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman N. C., Sleiman H. F. (2018). DNA nanotechnology. Nat. Rev. Mat. 3, 17068. 10.1038/natrevmats.2017.68 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shangguan D., Cao Z., Meng L., Mallikaratchy P., Sefah K., Wang H., et al. (2008). Cell-specific aptamer probes for membrane protein elucidation in cancer cells. J. Proteome Res. 7, 2133–2139. 10.1021/pr700894d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldevilla M. M., de Caso D. M. C., Menon A. P., Pastor F. (2018). Aptamer-iRNAs as therapeutics for cancer treatment. Pharmaceuticals 11, 108. 10.3390/ph11040108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldevilla M. M., Hervas S., Villanueva H., Lozano T., Rabal O., Oyarzabal J., et al. (2017). Identification of LAG3 high affinity aptamers by HT-SELEX and conserved motif accumulation (CMA). PLoS One 12, e0185169. 10.1371/journal.pone.0185169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldevilla M. M., Villanueva H., Bendandi M., Inoges S., Lopez-Diaz de Cerio A., Pastor F. (2015). 2-fluoro-RNA oligonucleotide CD40 targeted aptamers for the control of B lymphoma and bone-marrow aplasia. Biomaterials 67, 274–285. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X. R., Liu C., Wang N., Huang H., He S. Y., Gong C. Y., et al. (2021). Delivery of CRISPR/cas systems for cancer gene therapy and immunotherapy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 168, 158–180. 10.1016/j.addr.2020.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y., Zhu Z., An Y., Zhang W., Zhang H., Liu D., et al. (2013). Selection of DNA aptamers against epithelial cell adhesion molecule for cancer cell imaging and circulating tumor cell capture. Anal. Chem. 85, 4141–4149. 10.1021/ac400366b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soundararajan S., Chen W., Spicer E. K., Courtenay-Luck N., Fernandes D. J. (2008). The nucleolin targeting aptamer AS1411 destabilizes bcl-2 messenger RNA in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 68, 2358–2365. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S., Liu H., Hu Y., Wang Y., Zhao M., Yuan Y., et al. (2022). Selection and identification of a novel ssDNA aptamer targeting human skeletal muscle. Bioact. Mat. 20, 166–178. 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2022.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan W., Donovan M. J., Jiang J. (2013). Aptamers from cell-based selection for bioanalytical applications. Chem. Rev. 113, 2842–2862. 10.1021/cr300468w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel K. W., Hernandez L. I., Dassie J. P., Thiel W. H., Liu X., Stockdale K. R., et al. (2012). Delivery of chemo-sensitizing siRNAs to her2+-breast cancer cells using RNA aptamers. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 6319–6337. 10.1093/nar/gks294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ucuzian A. A., Gassman A. A., East A. T., Greisler H. P. (2010). Molecular mediators of angiogenesis. J. Burn Care Res. 31, 158–175. 10.1097/bcr.0b013e3181c7ed82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandghanooni S., Barar J., Eskandani M., Omidi Y. (2020). Aptamer-conjugated mesoporous silica nanoparticles for simultaneous imaging and therapy of cancer. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 123, 115759. 10.1016/j.trac.2019.115759 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Varmira K., Hosseinimehr S. J., Noaparast Z., Abedi S. M. (2013). A HER2-targeted RNA aptamer molecule labeled with 99mTc for single-photon imaging in malignant tumors. Nucl. Med. Biol. 40, 980–986. 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2013.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varmira K., Hosseinimehr S. J., Noaparast Z., Abedi S. M. (2014). An improved RadioLabelled RNA aptamer molecule for HER2 imaging in cancers. J. Drug Target. 22, 116–122. 10.3109/1061186X.2013.839688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D. L., Song Y. L., Zhu Z., Li X. L., Zou Y., Yang H. T., et al. (2014). Selection of DNA aptamers against epidermal growth factor receptor with high affinity and specificity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 453, 681–685. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.09.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Bing T., Zhang N., Sheng L., He J., Liu X., et al. (2019). The mechanism of the selective anti-proliferation effect of guanine-based biomolecules and its compensation. ACS Chem. Biol. 14, 1164–1173. 10.1021/acschembio.9b00062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R., Zhu G., Mei L., Xie Y., Ma H., Ye M., et al. (2014). Automated modular synthesis of Aptamer−Drug conjugates for targeted drug delivery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 2731–2734. 10.1021/ja4117395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Han Q., Yu N., Li J., Yang L., Yang R., et al. (2015). Aptamer-conjugated graphene oxide-gold nanocomposites for targeted chemo-photothermal therapy of cancer cells. J. Mat. Chem. B 3, 4036–4042. 10.1039/c5tb00134j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng W., He S., Song H., Li X., Cao L., Hu Y., et al. (2018). Aligned carbon nanotubes reduce hypertrophic scar via regulating cell behavior. ACS Nano 12, 7601–7612. 10.1021/acsnano.7b07439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wengerter B. C., Katakowski J. A., Rosenberg J. M., Park C. G., Almo S. C., Palliser D., et al. (2014). Aptamer-targeted antigen delivery. Mol. Ther. 22, 1375–1387. 10.1038/mt.2014.51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y.-X., Zhang D., Hu X., Peng R., Li J., Zhang X., et al. (2021). Multicolor two-photon nanosystem for multiplexed intracellular imaging and targeted cancer therapy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 12569–12576. 10.1002/anie.202103027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Sefah K., Liu H., Wang R., Tan W. (2010). DNA Aptamer−Micelle as an efficient detection/delivery vehicle toward cancer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 5–10. 10.1073/pnas.0909611107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang D., Shigdar S., Qiao G., Wang T., Kouzani A. Z., Zhou S. F., et al. (2015). Nucleic acid aptamer-guided cancer therapeutics and diagnostics: The next generation of cancer medicine. Theranostics 5, 23–42. 10.7150/thno.10202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xuan W., Peng Y., Deng Z., Peng T., Kuai H., Li Y., et al. (2018). A basic insight into aptamer-drug conjugates (ApDCs). Biomaterials 182, 216–226. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xuan W., Xia Y., Li T., Wang L., Liu Y., Tan W., et al. (2020). Molecular self-assembly of bioorthogonal aptamer-prodrug conjugate micelles for hydrogen peroxide and pH-independent cancer chemodynamic therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 937–944. 10.1021/jacs.9b10755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C., Zhao H., Sun Y., Wang C., Geng X., Wang R., et al. (2022). Programmable manipulation of oligonucleotide–albumin interaction for elongated circulation time. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, 3083–3095. 10.1093/nar/gkac156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H., Liu H., Kang H., Tan W. (2008). Engineering target-responsive hydrogels based on aptamer-target interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 6320–6321. 10.1021/ja801339w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Tseng Y.-T., Suo G., Chen L., Yu J., Chiu W.-J. (2015). Photothermal therapeutic response of cancer cells to aptamer-gold nanoparticle-hybridized graphene oxide under NIR illumination. ACS Appl. Mat. Interfaces 7, 5097–5106. 10.1021/am508117e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Yang M., Pang B., Vara M., Xia Y. (2015). Gold nanomaterials at work in biomedicine. Chem. Rev. 115, 10410–10488. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Yang X., Yang Y., Yuan Q. (2018). Aptamer-functionalized carbon nanomaterials electrochemical sensors for detecting cancer relevant biomolecules. Carbon 129, 380–395. 10.1016/j.carbon.2017.12.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yao C., Tang H., Wu W., Tang J., Guo W., Luo D., et al. (2020). Double rolling circle amplification generates physically CrossLinked DNA network for stem cell fishing. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 3422–3429. 10.1021/jacs.9b11001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B., Luo Z., Liu J., Ding X., Li J., Cai K., et al. (2014). Cytochrome c end-capped mesoporous silica nanoparticles as redox-responsive drug delivery vehicles for liver tumor-targeted triplex therapy in vitro and in vivo . J. Control. Release 192, 192–201. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.06.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Zhao Y., Xu X., Xu R., Li H., Teng X., et al. (2020). Cancer diagnosis with DNA molecular computation. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 709–715. 10.1038/s41565-020-0699-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N., Bing T., Liu X., Qi C., Shen L., Wang L., et al. (2015). Cytotoxicity of guanine-based degradation products contributes to the antiproliferative activity of guanine-rich oligonucleotides. Chem. Sci. 6, 3831–3838. 10.1039/C4SC03949A [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P., Cheng F., Zhou R., Cao J., Li J., Burda C., et al. (2014). DNA-Hybrid-gated multifunctional mesoporous silica nanocarriers for dual-targeted and microRNA-responsive controlled drug delivery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 2371–2375. 10.1002/anie.201308920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P., Zhao N., Zeng Z., Feng Y., Tung C. H., Chang C. C., et al. (2009). Using an RNA aptamer probe for flow cytometry detection of CD30-expressing lymphoma cells. Lab. Invest. 89, 1423–1432. 10.1038/labinvest.2009.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Xu J., Le V. M., Gong Q., Li S., Gao F., et al. (2019). EpCAM aptamer-functionalized cationic LiposomeBased nanoparticles loaded with miR-139−5p for targeted therapy in colorectal cancer. Mol. Pharm. 16, 4696–4710. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.9b00867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J., Rossi J. (2017). Aptamers as targeted therapeutics: Current potential and challenges. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 16, 181–202. 10.1038/nrd.2016.199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu G., Zhang H., Jacobson Q., Wang Z., Chen H., Yang X., et al. (2017). Combinatorial screening of DNA aptamers for molecular imaging of HER2 in cancer. Bioconjug. Chem. 28, 1068–1075. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.6b00746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Y., Huang B., Cao L., Deng Y., Su J. (2020). Tailored mesoporous inorganic biomaterials: Assembly, functionalization and drug delivery engineering. Adv. Mat. 30, 2005215. 10.1002/adma.202005215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]