Abstract

Shiga toxin producing bacteria are potential causes of serious human disease such as hemorrhagic colitis, severe inflammations of ileocolonic regions of gastrointestinal tract, thrombocytopenia, septicemia, malignant disorders in urinary ducts, hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS). Shiga toxin 1 (stx1), shiga toxin 2 (stx2), or a combination of both are responsible for most clinical symptoms of these diseases. A lot of methods have been developed so far to detect shiga toxins such as cell culture, ELISA, and RFPLA, but due to high costs and labor time in addition to low sensitivity, they have not received much attention. In this study, PCR-ELISA method was used to detect genes encoding shiga toxins1 and 2 (stx1 and stx2). To detect stx1 and stx2 genes, two primer pairs were designed for Multiplex-PCR then PCR-ELISA. PCR products (490 and 275, respectively) were subsequently verified by sequencing. Sensitivity and specificity of PCR-ELISA method were determined by using genome serial dilution and Enterobacteria strains. PCR-ELISA method used in this study proved to be a rapid and precise approach to detect different types of shiga toxins and can be used to detect bacterial genes encoding shiga toxins.

Keywords: Shigella dysenteriae, E.coli O157:H7, PCR-ELISA, Diagnostic methods

Introduction

Shiga toxins belong to a large family of bacterial toxins with two major groups, stx1 and stx2.1 These virulence factors are mainly produced by Shigella dysenteriae and Shigatoxigenic group of Escherichia coli like E. coli O157:H7 which are able to cause infectious diseases.2, 3 The toxin is one of the AB5 toxins and has binding (B) and catalytic domains (A). The pentameric B subunit of the toxin is responsible for receptor binding and intracellular trafficking of the holotoxins.4 The toxin binds to Gb3 located on cell surfaces and is introduced by endocytic uptake. N-glycosidase activity of the A subunit inhibits protein synthesis in the cell and causes cell death.5 In some cells these toxins also trigger cytokine synthesis and induce apoptosis, which is caused by ribotoxic stress.6 The gene encoding toxin in Shigella dysenteriae is chromosomal. However stx gene in E. coli O157:H7 is associated with a prophage.7 Different subtypes of shiga toxin are identified as stx1, stx1c, stxfc, stx2, stx2e, stx2d and stx2g.8 Infections by shiga toxins producing bacteria have worldwide prevalence and are widespread in developing countries such as south-eastern Asian countries, Indian subcontinent, South Africa, central Asia, and Bangladesh.9 Infection of Shiga toxin producing bacteria is a major health concern even in developed countries all over the world. These bacteria are potential cause of diarrhea, hemorrhagic colitis, severe inflammations of ileocolonic regions of the gastrointestinal tract, thrombocytopenia, septicemia, central nervous system (CNS) involvement, malignant disorders in urinary ducts, and hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS).10 urinary tract infection by EHEC is mainly generated by E. coli O157. In children under five years old and adults over 60, as they have the receptor, it causes kidney function deficiency and has a death rate of 5–10%.11 Cows, goats and other animals can naturally be a source of stx producing E. coli and other animals such as crabs also play a role in its transfer.12 Transfer between humans can also take place.13 Since shiga toxins cause many diseases, especially in children and immunocompromised elderly people, a rapid and sensitive diagnostic method with prognostic information would be rather useful. So far, many different detection methods such as cell culture, serological and molecular methods such as RPLA, real-time, PCR, hybridization have been utilized to detect shiga toxins or their respective genes.14 Yet, all these methods have their own shortcomings as they are time-consuming, quite costly and have limitations in handling many samples simultaneously. At present, although molecular methods such as PCR and hybridization, despite being less time-consuming, less costly, and more sensitive, they are not suitable as they rely on agarose electrophoresis with carcinogen ethidium bromide, a major health threat for lab personnel, and does not allow analysis of many samples at a time in case of epidemic breakouts.15 Nevertheless, real-time PCR despite 100% specificity and high sensitivity has not gained much attention because of high costs of fluorescent material and shortage of expert personnel.16 To overcome shortcomings of the aforementioned methods, PCR-ELISA is an appropriate alternative approach for detecting stx genes, which is safe and non-radioactive. PCR-ELISA is more convenient for rapid and reliable detection and quantification of pathogen-specific gene sequences.17, 18 Besides having been used in medical and food industries, PCR-ELISA has also been used in the veterinary industry.19

In this study, specific primers and probes for stx genes, amplification and labeling of products DIG-dUTP, hybridization of streptavidin with biotinylated probes and detection with antibody against conjugated digoxigenin and peroxidase in microtiter plates were designed. We identified specific sequences of stx genes in a large number of samples using small amounts simultaneously with considerable sensitivity and short turnaround time.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains

Shigella dysenteriae and E. coli O157:H7 strains were provided from Shahed University, Tehran, Iran and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella typhimurium, Salmonella paratiphi, Klebsiella pneumonia and Vibrio cholera strains were provided by Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. The strains were verified by biochemical and immunologic methods.

Extraction of bacterial genomic DNA

To extract genomic DNA from Shigella dysenteriae and E. coli O157:H7 bacteria were incubated in liquid LB medium for 18 h in 37 °C. Bacterial culture was centrifuged in 3000 rpm for 5 min. The pellet was resuspended in 300 μL TE buffer followed by lysis solution containing 10 μL lysozyme (10 mg/mL), 200 μL SDS 20%, 3 μL proteinase K and incubated in 37 °C for 60 min. DNA was purified by extraction with an equal volume of phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) in the presence of 5 M sodium perchlorate. A 1/10 volume of 3 M sodium acetate and 2 volumes of absolute ethanol were added and incubated in −20 °C for 13 h. The genome was pelleted by centrifugation, washed with 70% ethanol and dried. Finally, DNA samples were dissolved in 100 μL TE buffer and, to eliminate RNA, 3 μL RNase A was added and the tubes were incubated in 37 °C for 30 min.

The concentration and purity of the DNA samples were determined spectrophotometrically at A260 and A280 by NanoDrop 2000, Thermo Scientific (USA).

Primer and probe design

To design primers and the nucleic-acid sequencing probes, central parts of shiga toxin genes were used as template. Features in the designed primers such as GC content; Tm, ΔG, etc. were checked by DNASIS and Oligo7 softwares. The primer and probe sequences are illustrated in Table 1. The oligonucleotides were supplied by CinnaClone (IRAN).

Table 1.

PCR primers and hybridization capture probe for stx1 and stx2 genes.

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence | Nucleotide position | Expect product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ah stx1F | TTGTTTGCAGTTGATGTCAGAGG | 210–233 | 275 |

| Ah stx1R | CAGGCAGGACACTACTCAACCTTC | 676–700 | |

| Ah stx2F | TTGCTGTGGATATACGAGGGC | 214–235 | 490 |

| Ah stx2R | CGCCAGATATGATGAAACCAGTG | 466–489 | |

| p Stx1 | Biotin-TGTTGCAGGGATCAGTCGTACG | 422–444 | – |

| p Stx2 | Biotin-CATATATCAGTGCCCGGTGTG | 355–376 | – |

Isolation and amplification of stx1 and stx2 genes by PCR

PCR reagents in a final volume of 25 μL included: 1 μL template DNA, 0.5 μL Taq DNA polymerase (5 U/μL), 1 μL of each primer (10 pmol/μL), 1 μL dNTP mixture, 2.5 μL 10× PCR buffer, 1.5 μL MgCl2 (50 mM) and 16.5 μL sterile DDW. Thermal cycling of amplification mixture was performed in 30 cycles.20

The PCR program was carried out at 94 °C for 3 min followed denaturing for 45 s at 94 °C, annealing for 45 s at 59 °C and an extension for 1 min at 72 °C. The final extension was at 72 °C for 5 min. PCR products were electrophoresed in 1% agarose followed by staining with ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/mL) then visualized under ultraviolet light, and the results were recorded by photography. PCR products were verified by sequencing. For labeling of PCR products, the reaction of PCR was performed by dNTP mixture containing digoxigenin labeling mix (Digoxigenin dNTPs, Roche, Germany) with the same condition.

Detection of PCR products by ELISA

One microgram avidin were coated on ELISA plates, one well was placed as a negative control. Then, plates were washed with PBS (pH 7.2) containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBST) and the blocked by 3% BSA buffer. In addition, 10 μL of each labeled product of stx1 and stx2 genes were added to 90 μL 1× SSC buffer in 1.5 mL tubes and incubated in boiling water for 10 min and then 5 min on ice. In the next step, 10 μL of stx1 and stx2 probes were added to each tube and after 2 h in 60 °C, 100 μL from this hybridization solution were added to each well and after 1 h in 37 °C, it was washed with 20% BPST buffer 3 times. A 1/1000 solution of anti-digoxigenin antibody conjugated with peroxides in PBST buffer was prepared and 100 μL of this solution was added to each well (including controls) and after 1 h in 37 °C the plates were washed and dried as described earlier. 100 μL of substrate solution (2 mg OPD, 100 μL detection buffer, 5 μL 30% hydrogen peroxide) was added to wells. 100 μL of 1 M H2SO4 was added to stop the reaction.21 The optical density was measured at 490 nm using an ELISA reader (Dynex Technologies, Guornesey, Channel Islands and Great Britain).

Evaluation PCR specificity and sensitivity

To determine the specificity, PCR was carried out with genomic DNA extracted from Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella typhimurium, Salmonella paratiphi C, Klebsiella pneumonia and Vibrio cholera. Products were analyzed on 1% agarose gel. To determine the minimum genomic DNA concentration that could be detected by the method, serially diluted genomic DNA in TE buffer (pH = 8) was used as PCR template and the product was analyzed on 1% agarose gel.

Sensitivity evaluation of PCR-ELISA technique using labeled PCR products of stx1 and stx2

To determine the detection limit for stx gene, genomic DNA was extracted and tenfold serial dilutions containing 108 ng/μL to 0.108 pg/μL and 156 ng/μL to 0.156 pg/μL of E. coli O157:H7 and Shigella dysenteriae genomic DNA, respectively, were prepared and all the steps were carried out as described previously.22

PCR-ELISA specificity evaluation using bacterial strains

To evaluate specificity of PCR-ELISA, E. coli O157:H7, Shigella dysenteriae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella typhimurium, Salmonella paratiphi C and Klebsiella pneumonia strains were grown in LB medium. Genomic DNAs were extracted and after evaluating their concentration by NanoDrop, 10−2 fold dilution was prepared as templates. The PCR was carried out according to mentioned protocols and the products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis and ELISA.22

Clinical samples analysis

In this study 63 positive samples of Shigella dysenteriae and E. coli O157:H7 obtained from stool and urine cultures were analyzed. Samples were gathered from Mazandaran hospitals in a 3-month period between January and March of 2013. Age groups included children between 8 months to 10 years old, adults between 20 and 30 and between 50 and 90 years old (Table 2). Samples were transferred to the lab, cultured, and after growth were identified in differential and specific media and verified by specific antiserums. Following DNA extraction by boiling method, PCR-ELISA was carried out. Data analysis was performed on SPSS.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of patients.

| Patient ID | Age (years) | Sex | Type of specimen | Clinical manifestations |

Stx genotype | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diarrhea | Abdominal pain | |||||

| 2 | 30 | F | Bloody stool | + | + | Stx1/Stx2 |

| 3 | 20 | F | Bloody stool | + | + | Stx1/Stx2 |

| 8 | 8 | M | Bloody stool | + | + | Stx1/Stx2 |

| 10 | 6 | M | Bloody stool | + | + | Stx2 |

| 14 | 20 | F | Bloody stool | + | − | Stx2 |

| 15 | 56 | M | Bloody stool | + | − | Stx2 |

| 18 | 20 | M | Bloody stool | + | − | Stx2 |

| 20 | 6 | F | Bloody stool | + | + | Stx2 |

| 23 | 9 | M | Watery stool | + | − | Stx2 |

| 27 | 8 | M | Bloody stool | + | + | Stx1/Stx2 |

| 32 | 57 | M | Bloody stool | + | − | Stx2 |

| 35 | 9 | M | Bloody stool | + | − | Stx2 |

| 43 | 25 | F | Bloody stool | + | + | Stx2 |

| 47 | 50 | F | Bloody stool | + | − | Stx2 |

| 53 | 7 | M | Bloody stool | + | + | Stx2 |

| 55 | 55 | F | Watery stool | + | − | Stx2 |

| 59 | 8 | M | Bloody stool | + | − | Stx2 |

Results

PCR

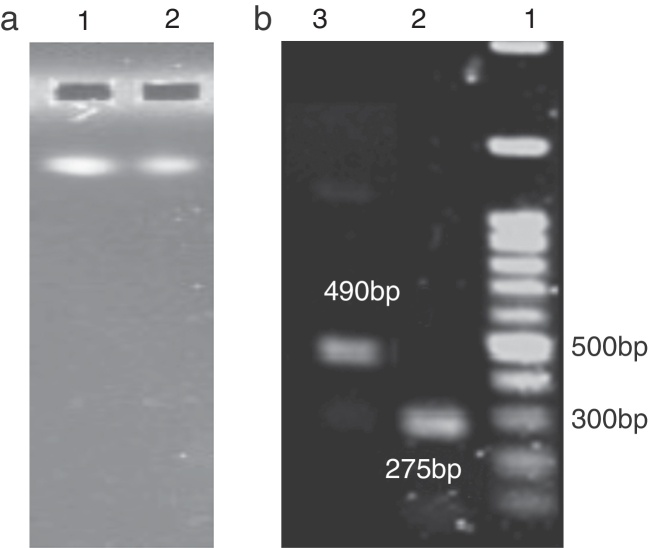

DNA from extracted genome of bacteria cultured in LB medium was available in large quantities and was of good quality. The purity of the DNA samples was confirmed by absorbance (A260/A280) ratio, which was 1.8–2.0. PCR was performed for each strain with specific primers. Each PCR product was obtained as clear band at 275 and 490 bp generated by stx2 and stx1 genes respectively (Fig. 1b). The sizes of PCR products were the same as predicted.

Fig. 1.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of extracted E. coli O157:H7 and Shigella dysenteriae genomic DNA and analysis of PCR products. (a) Lane 1, E. coli O157:H7 genomic DNA; Lane 2, Shigella dysenteriae's genomic DNA. (b) Lane 1, 100 bp DNA ladder; Lane 2, PCR product (275 bp) for stx2; Lane 3, PCR product (490 bp) for stx1.

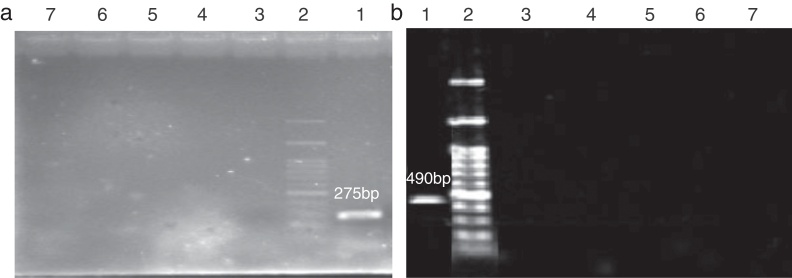

Specificity of PCR

After validation of PCR products, specificity of the reaction was examined using genomes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella typhimurium, Salmonella paratiphi C, Klebsiella pneumonia and Vibrio cholera. As shown in Fig. 2, no cross-reaction was found between the individual primers and non-target pathogens in the PCR.

Fig. 2.

Specificity of PCR detection of E. coli O157:H7 (a) and Shigella dysenteriae (b). Lane 1, positive control; Lane 2, 100 bp DNA ladder; Lane 3, Pseudomonas aeruginosa; Lane 4, Klebsiella pneumonia; Lane 5, Vibrio cholera; Lane 6, Salmonella typhimurium; Lane 7, Salmonella paratyphi C.

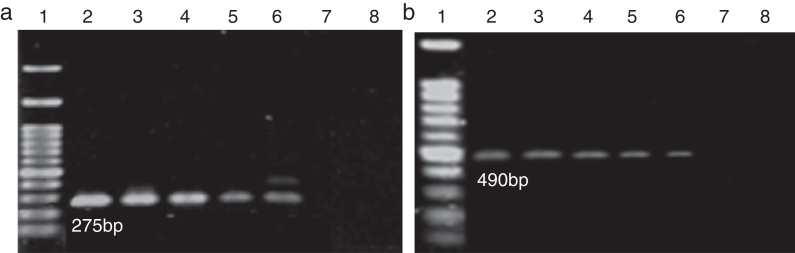

Sensitivity of PCR

After preparing a serial dilution from E. coli O157:H7 and Shigella dysenteriae at a primary concentration of 108 ng/μL and 156 ng/μL, the PCR reactions were performed on these dilutions and the results are displayed in Fig. 3. Regarding concentrations of the primary sample (108 ng/μL and 156 ng/μL), sensitivity of the reaction was calculated as 1.08 pg/μL and 1.56 pg/μL, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Sensitivity of PCR detection using genomic DNA for E. coli O157:H7 (a) and Shigella dysenteriae (b), Lane 1, 100 bp DNA ladder; Lane 2, 10−1 dilution; Lane 3, 10−2 dilution; Lane 4, 10−3 dilution; Lane 5, 10−4 dilution; Lane 6, 10−5 dilution; Lane 7, 10−6 dilution; Lane 8, 10−7 dilution.

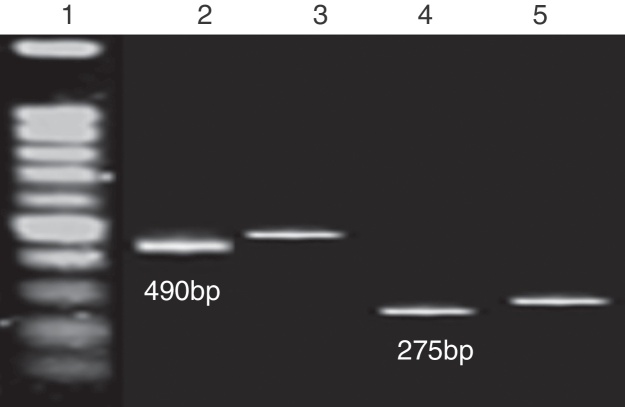

Specific PCR with dNTP DIG labeling mix

A PCR reaction was performed with digoxigenin labeling mix and the results were analyzed on 1% agarose gel (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Representative electrophoretic gels of PCR products labeled with digoxigenin. Lane 1, 100 bp DNA ladder; Lane 2, PCR product of stx1 from Shigella dysenteriae genomic DNA; Lane 3, PCR product of stx1 from Shigella dysenteriae genomic DNA labeling with dNTP DIG mix; Lane 4, PCR product of stx2 from E. coli O157:H7 genomic DNA; Lane 5, PCR product of stx2 from E. coli O157:H7 genomic DNA labeling with dNTP DIG mix.

PCR-ELISA specificity and sensitivity assay

The specificity of the PCR-ELISA was analyzed using genomes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella typhimurium, Salmonella paratiphi C, Klebsiella pneumonia and Vibrio cholera.

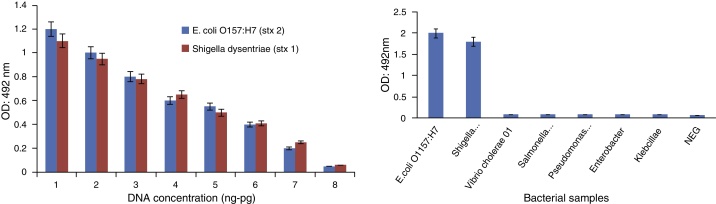

To determine the minimum detectable concentration of genomic DNA of Shigella dysenteriae and E. coli O157:H7, serial dilutions were subjected to the PCR-ELISA technique. The results (Fig. 5) demonstrate the possibility of detecting 1.08 pg/μL and 1.56 pg/μL E. coli O157:H7 and Shigella dysenteriae, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Specificity and sensitivity of PCR-ELISA assay for stx2 and stx1 hybridization. (a) Sensitivity of PCR-ELISA which is derived from serial dilution of DNA extraction of E. coli O157:H7 from 108 ng to 0.108 pg and Shigella dysenteriae from 156 ng to 0.156 pg. (b) Specificity of PCR-ELISA assay for stx2 and stx1 detection using bacterial samples.

Clinical results

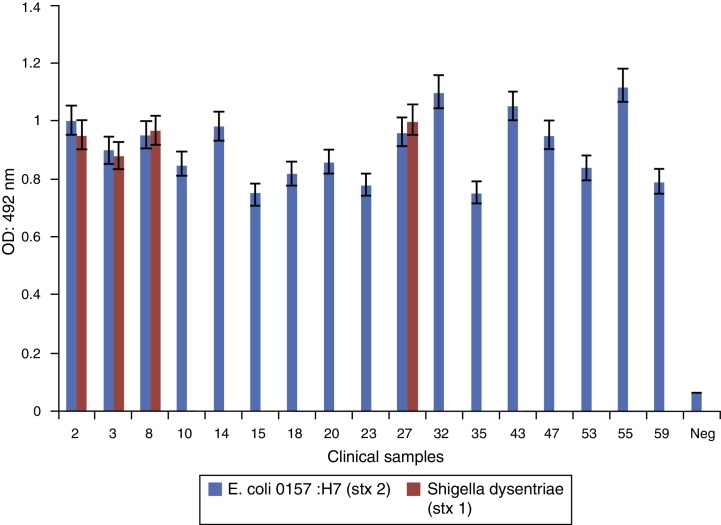

A total of 63 clinical samples were collected and screened for the presence of E. coli O157:H7 and Shigella dysenteriae strains.

Seventeen (26.98%) samples were detected as stx positive. Age distribution of the patients ranged from <1 to 90 years. E. coli O157:H7 and Shigella dysenteriae infected patients had an average age of 23.17 years, and 47.05% were less than 10 years old (Table 2). The most common symptoms were bloody stools (88.23%) and abdominal pain (47.05%). Sex distribution of E. coli O157:H7 and Shigella dysenteriae infected patients were 7 females (41.18%), and 10 males (58.82%). Bacteriological culture results were compared to those obtained by PCR-ELISA. Results obtained from PCR-ELISA assay (Fig. 6) and from selective culture were compared. There was a significant association between PCR-ELISA and culture results for detecting and screening E. coli O157:H7 and Shigella dysenteriae. (p < 0.001).

Fig. 6.

PCR-ELISA analysis of clinical samples, E. coli O157:H7 (stx 2) and Shigella dysenteriae. (stx 1). Negative controls are also indicated. Assay cut-off was calculated by replicate analysis of negative samples (OD: 0.125).

Discussion

Shiga toxin producing bacteria infection is a major health concern even in developed countries all over the world.9, 23, 24 With increasing reports of E. coli O157:H7 and Shigella dysenteriae infections, great attention has been given to the development of methods for detecting these pathogens and approaches for prevention and treatment of these infections. This study was intended to reach part of these aims.

In recent years, ELISA test has been designed to detect shiga toxins directly in stool samples. The test is rapid and has a good potential for shiga toxin detection since it can detect the presence of shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) or other shiga toxin-producing bacteria. Since shiga toxin type differentiation requires high cost monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies it is not widely used. Hybridization method is an effective, highly sensitive and specific molecular method for precise detection of shiga toxins, and uses non-radioactive substances such as digoxigenin and biotin. However, since it is not suitable for using in large number of clinical samples, this method is not used in many clinical labs.25

In contrast to serological and microbiological tests, PCR provides a rapid and sensitive alternative. This technique, first developed by Karch and Meyer, includes a primer pair from a conserved region of stx1 and stx2 in homologous genes whose main defects were low Tm and ineffectiveness in different types of shiga toxins.15 In that regard, to detect different types of shiga toxins it is necessary to design a multiplex PCR with at least two pairs of primers to detect shiga toxin gene. The first study on multiplex PCR detection shiga toxins was by Cebula et al. who designed specific primers and used a fragment as positive internal control. Nonetheless, primers were only able to detect stx2.26 Subsequent studies were carried out by Paton et al., Pass et al., Philot et al., and Belanger et al. Their main disadvantage was that all fragments were low-size and were hard to dissolve in agarose gel.14, 27, 28 The primers that we designed for this study, after comparison with available data from gene banks, using software and experiment on clinical samples, proved to lack the above mentioned disadvantages and to be able of amplify different shiga toxin genes. In addition, these amplified fragments were easily dissolved in agarose gel and both stx1 and stx2 genes could be simultaneously detected in clinical samples. One potential problem of PCR is the presence of inhibitors, which may cause false results of the test. In Gram negative bacteria different lipids, carbohydrates, and proteins present in cell wall can act as inhibitors and reduce the sensitivity of the reaction.29 To overcome these limitations and to increase sensitivity, bacterial genome must be purified before carrying out the reaction. Frank et al. in 1998 used the boiling method to extract genomic DNA; however, in this method inhibitors could not be eliminated.30 Wang et al. in 2002 used SDS, lysozyme, tris, glucose and EDTA for extraction which increased sensitivity to 100 pmol/μL.31 In 2011, Marzony et al. removed inhibitors and extracted genomic DNA by using CTAB and 5 M NaCl and reported a sensitivity of 2.1 pg/μL.32 Comparing PCR-ELISA with Vero cell assays, Fach et al.33 showed that results with PCR were obtained within 24 h whereas with Vero cell assays results were available only after five days. Furthermore, Beilei et al. developed PCR-ELISA methods to detect Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) in food, where 105 CFU of STEC per gram of ground beef detected without any culture enrichment by PCR-ELISA.34

In this study, inhibitors were effectively eliminated by using TE buffer, lysozyme, 20% SDS, proteinase K, RNase A, 3 M Sodium Acetate and cold isopropanol. Consequently, sensitivity of the test improved to 1.08 pg/μL. PCR-ELISA was successfully carried out with genomic DNA extracted from clinical samples; from Shigella dysenteriae, a 490 bp fragment was amplified as mentioned earlier. For E. coli O157:H7 both 490 and 275 bp fragments were amplified demonstrating that it can produce both toxins. PCR-ELISA correctly confirmed the specific stx1 and stx 2 genes. Non-positive results for other strains indicate that the tests are highly specific. Moreover, we have compared the performance of PCR-ELISA with standard agarose gel electrophoresis. PCR-ELISA assay was more sensitive than the gel electrophoresis. Our data indicate that PCR-ELISA is highly specific, and has higher sensitivity than conventional gel electrophoresis. By offering shorter turnaround time and high sensitivity, PCR-ELISA has the potential to serve as a powerful detection tool in medicine and in food and agricultural industries.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by Applied Microbiology Research Center, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, and the part of this project was dissertation of Askary ahmadpour, submitted to Applied Microbiology Research Center, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the MSc in microbiology.

References

- 1.Paton J.C., Paton A.W. Pathogenesis and diagnosis of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:450–479. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.3.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karmali M.A. Infection by Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. Mol Biotechnol. 2004;26:117–122. doi: 10.1385/MB:26:2:117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karmali M.A. Prospects for preventing serious systemic toxemic complications of shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infections using shiga toxin receptor analogues. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:355–359. doi: 10.1086/381130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lingwood C.A. Shiga toxin receptor glycolipid binding. Methods Mol Med. 2002;73:165–186. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-316-x:165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Endo Y., Tsurugi K., Yutsudo T., Takeda Y., Ogasawara T., Igarashi K. Site of action of a Vero toxin (VT2) from Escherichia coli O157:H7 and of Shiga toxin on eukaryotic ribosomes. Eur J Biochem. 1988;171:45–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb13756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foster G.H., Tesh V.L. Shiga toxin 1-induced activation of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase and p38 in the human monocytic cell line THP-1: possible involvement in the production of TNF-α. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;71:107–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang A., Friesen J., Brunton J. Characterization of a bacteriophage that carries the genes for production of Shiga-like toxin 1 in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:4308–4312. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.9.4308-4312.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gobius K.S., Higgs G.M., Desmarchelier P.M. Presence of activatable Shiga toxin genotype (stx2d) in Shiga toxigenic Escherichia coli from livestock sources. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:3777–3783. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.8.3777-3783.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sack D., Hoque S., Etheridge M., Huq A. Is protection against shigellosis induced by natural infection with Plesiomonas shigelloides? Lancet. 1994;343:1413–1415. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92531-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siegler R.L. Spectrum of extrarenal involvement in postdiarrheal hemolytic-uremic syndrome. J Pediatrics. 1994;125:511–518. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(94)70001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siegler R.L. Postdiarrheal Shiga toxin-mediated hemolytic uremic syndrome. JAMA. 2003;290:1379–1381. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.10.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Urdahl A., Beutin L., Skjerve E., Zimmermann S., Wasteson Y. Animal host associated differences in Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolated from sheep and cattle on the same farm. J Appl Microbiol. 2003;95:92–101. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2003.01964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar H., Karunasagar I., Karunasagar I., Teizou T., Shima K., Yamasaki S. Characterisation of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) isolated from seafood and beef. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2004;233:173–178. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Philpott D., Ebel F. Springer; 2003. E. coli: shiga toxin methods and protocols. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karch H., Meyer T. Single primer pair for amplifying segments of distinct Shiga-like-toxin genes by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:2751–2757. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.12.2751-2757.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Croxen M.A., Finlay B.B. Molecular mechanisms of Escherichia coli pathogenicity. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:26–38. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daly P., Collier T., Doyle S. PCR-ELISA detection of Escherichia coli in milk. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2002;34:222–226. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.2002.01074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perelle S., Dilasser F., Malorny B., Grout J., Hoorfar J., Fach P. Comparison of PCR-ELISA and LightCycler real-time PCR assays for detecting Salmonella spp. in milk and meat samples. Mol Cell Probes. 2004;18:409–420. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kobets T., Badalová J., Grekov I., Havelková H., Svobodová M., Lipoldová M. Leishmania parasite detection and quantification using PCR-ELISA. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:1074–1080. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahmadpour A., Amani J., Imani Fooladi A.A., Sedighian H., Nazarian S. Detection of Shigella dysenteriae and E. coli O157:H7 toxins by multiplex PCR method in clinical samples. Iran J Med Microbiol. 2013;7:41–51. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mousavi S.L., Nazarian S., Amani J., Rahgerd Karimi A. Rapid screening of toxigenic vibrio cholerae O1 strains from south Iran by PCR-ELISA. Iran Biomed J. 2008;12:15–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mousavi S.L., Salimiyan J., Rahgerdi A.K., Amani J., Nazarian S., Ardestani H. A rapid and specific PCR-ELISA for detecting Salmonella typhi. Iran J Clin Infect Dis. 2006;1:113–119. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sandvig K. Shiga toxins. Toxicon. 2001;39:1629–1635. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(01)00150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kargar M., Daneshvar M., Homayoun M. Surveillance of virulence markers and antibiotic resistance of shiga toxin producing E. coli O157:H7 Strains from Meats Purchase in Shiraz. ISMJ. 2011;14:76–83. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jackson M.P. Detection of Shiga toxin-producing Shigella dysenteriae type 1 and Escherichia coli by using polymerase chain reaction with incorporation of digoxigenin-11-dUTP. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:1910–1914. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.9.1910-1914.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cebula T.A., Payne W.L., Feng P. Simultaneous identification of strains of Escherichia coli serotype O157:H7 and their Shiga-like toxin type by mismatch amplification mutation assay-multiplex PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:248–250. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.1.248-250.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bélanger S.D., Boissinot M., Ménard C., Picard F.J., Bergeron M.G. Rapid detection of Shiga toxin-producing bacteria in feces by multiplex PCR with molecular beacons on the smart cycler. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:1436–1440. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.4.1436-1440.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong C.S., Jelacic S., Habeeb R.L., Watkins S.L., Tarr P.I. The risk of the hemolytic–uremic syndrome after antibiotic treatment of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1930–1936. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006293422601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tamminen M., Joutsjoki T., Sjöblom M., et al. Screening of lactic acid bacteria from fermented vegetables by carbohydrate profiling and PCR-ELISA. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2004;39:439–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2004.01607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Franck S.M., Bosworth B.T., Moon H.W. Multiplex PCR for enterotoxigenic, attaching and effacing, and Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains from calves. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1795–1797. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.6.1795-1797.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang G., Clark C.G., Rodgers F.G. Detection in Escherichia coli of the genes encoding the major virulence factors, the genes defining the O157:H7 serotype, and components of the type 2 Shiga toxin family by multiplex PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:3613–3619. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.10.3613-3619.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marzony E.T., Kamali M., Saadati M., Keihan A.H., Fooladi A.A.I., Sajjadi S. Single multiplex PCR assay to identify the shiga toxin. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2011;5:1794–1800. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fach P., Perelle S., Dilasser F., Grout J. Comparison between a PCR-ELISA test and the vero cell assay for detecting Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in dairy products and characterization of virulence traits of the isolated strains. J Appl Microbiol. 2001;90:809–818. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ge B., Zhao S., Hall R., Meng J. A PCR-ELISA for detecting Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. Microbes Infect. 2002;4:285–290. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(02)01540-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]