Abstract

Introduction

Since 1996 Brazil has provided universal access to free antiretroviral therapy, and as a consequence, HIV/AIDS patients’ survival rate has improved dramatically. However, according to scientific reports, a significant number of patients are still late presenting for HIV treatment, which leads to consequences both for the individual and society. Clinical and immunological characteristics of HIV patients newly diagnosed were accessed and factors associated with late presentation for treatment were evaluated.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was carried out in an HIV/AIDS reference center in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, in Southeastern Brazil from 2008 to 2010. Operationally, patients with late presentation (LP) for treatment were those whose first CD4 cell count was less than 350 cells/mm3 or presented an AIDS defining opportunistic infection. Patients with late presentation with advanced disease (LPAD) were those whose first CD4 cell count was less than 200 cells/mm3 or presented an AIDS defining opportunistic infection. LP and LPAD associated risk factors were evaluated using logistic regression methods.

Results

Five hundred and twenty patients were included in the analysis. The median CD4 cell count was 336 cells/mm3 (IQR: 130–531). Two hundred and seventy-nine patients (53.7%) were classified as LP and 193 (37.1%) as LPAD. On average, 75% of the patients presented with a viral load (VL) >10,000 copies/ml. In multivariate logistic regression analysis the factors associated with LP and LPAD were age, being symptomatic at first visit and VL. Race was a factor associated with LP but not with LPAD.

Conclusion

The proportion of patients who were late attending a clinic for HIV treatment is still high, and effective strategies to improve early HIV detection with a special focus on the vulnerable population are urgently needed.

Keywords: AIDS, Late presentation, HIV infection, CD4 cell count

Introduction

Since the early 1980s, after the first cases of infection by HIV were reported in Brazil, the Brazilian government response to the epidemic was forceful. It was based on early diagnosis, treatment and prevention, which were supported by participation from civil society and respect for human rights.1

In 1996 Brazil became the first developing country to ensure universal access to free antiretroviral therapy (ARV) guaranteed by the Federal Law 9313. Consequently, the survival rate among Brazilian AIDS patients has improved dramatically.2 In spite of preventive efforts and actions to early diagnose the infection, many patients are still late presenting for treatment.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11

It is estimated that there has been a decrease in the proportion of patients who present late for treatment in Brazil over recent years. According to surveillance data reports 29% of patients presented with CD4 cell count less than 200 cell/mm3 and at least half of patients presented with a CD4 cell count less than 350 cell/mm3 in 2012.11

It is difficult to compare the proportion of late diagnosis of HIV infection in different countries and even the trends over the years in a given country, since there are more than 20 criteria for this definition.12, 13, 14 This seems to be a worldwide problem. A recent meta-analysis of 44 studies in developed countries showed that the average CD4 cell count in the first visit for treatment has not increased meaningfully in the past 20 years and the majority of people still present with CD4 cell count less than 350 cells/mm3.15

Late diagnosis and thus delayed treatment may impact on the individual as well as on the society. Patients who start ARV with low CD4 cell count present higher morbidity and mortality and have poorer treatment response.13

The impact for society is that the treatment for late diagnosis increases costs for the health system in the short and long runs.16 In addition, those who present for treatment with more advanced disease have higher probability of transmission since they do not know about their infection and cannot adopt risk reduction precautions or lower their viral load as a consequence of ARV therapy.17

A better understanding of local data and the factors associated with patients late presenting for treatment are important. These could help ensuring public surveillance programs and to provide targeted intervention, focusing on individuals who are particularly at risk.

The objective of this study was to describe the social, demographic, clinical and immunological characteristics of patients recently diagnosed with HIV infection in a reference center for HIV/AIDS – Voluntary Counseling and Testing Site/Specialized Center in HIV Outclinic Patient Care (CTA/SAE) – in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais state, Brazil, from 2008 to 2010, and to determine factors associated with patients presenting late for HIV treatment.

Materials and methods

Subjects and settings

All patients who presented for the first time at CTA–SAE with a recent HIV diagnosis between January 1, 2008 and December 31 2010 were included.

Belo Horizonte is one of the most populated metropolitan areas in the country and is the capital city of Minas Gerais, a state in southeast Brazil. The HIV detection rates in the city are decreasing: in June 2013 it was 27.2 cases/100,000 inhabitants.11 Between 2002, when the service was implemented, and 2014, about 3300 patients have been registered at CTA–SAE, of which 2398 (72.7%) are currently using ARV. It is one of the three main clinics that provide HIV treatment in the Belo Horizonte metropolitan area, providing care for almost 20% of newly diagnosed HIV patients in the city.

Patients were eligible for the study if they were over 18 years old; had had a recent diagnosis of the HIV infection (defined as those who had been diagnosed in the previous 12 months); had initiated treatment at CTA–SAE between the 1 January 2008 and 31 December 2010, and had had at least one CD4 cell count or an AIDS defining opportunistic infection (CDC) registered between the diagnosis and one year thereafter.18 To include only patients newly diagnosed with HIV infection, several criteria were used to exclude patients who might have previously known about their HIV infection, or who had a routine screening, as during pregnancy.

Patients were excluded if registered at CTA–SAE for more than one year after the first positive HIV test; had no documented date for their HIV test; those tested through a pre-natal screening; and those who had attended another HIV/AIDS specialized center. Only patients with at least two visits to the center were included in the study. Ethical approval was obtained from local ethical committees.

Study design

A cross-sectional study of a historical cohort was carried out. All data was retrieved from clinical charts using standardized forms. Data abstracted from the charts were demographic information, clinical features, laboratory data (HIV viral load, CD4 cell counts, serology for syphilis, hepatitis B and C, and tuberculin skin test result) and time on ARV if it had been initiated after the first appointment at the clinic.

Definitions and variables of interest

Late presenters (LP) were those patients whose first CD4 cell count was less than 350 cells/mm3 and had an AIDS defining opportunistic infection were defined as late presenters (LP). Subjects who presented with a CD4 cell count less than 200 cells/mm3 or had an AIDS defining opportunistic infection were defined as late presenters with advanced disease (LPAD). Consequently, those patients whose first CD4 cell count was equal to or higher than 350 cell/mm3 were classified as non late presenters (NLP). This definition is in accordance with a 2011 European Late Presenters Consensus Definition.19

The following exposure variables were considered: year of HIV diagnosis; age at the time of HIV diagnosis; date of the first attendance to the clinic; gender; race; level of education; occupation; place of residence; be part of a self-reported HIV risk group; HIV viral load (VL); clinical features; reasons to be tested for HIV; hepatitis B (HBsAg and HBc antibody) and C serology (HCV antibody); syphilis (VDRL) and tuberculin skin test (TST).

Patients were categorized by age of the patient at the time of HIV diagnosis using the median age, race as white and non-white, years of schooling no education (illiterate), fewer than eight years, eight to eleven years, and more than 11 years, occupation as housewife, retired, unemployed, employed, student and other, and place of residence as Belo Horizonte city, Belo Horizonte metropolitan area, or other cities.

Only sexual exposure was considered as exposure risk category (heterosexual men, heterosexual women, and men who have sex with men – MSM) since there were only three patients (0.6%) of injecting drug users (IDU). The date of the first HIV test was considered as the date of HIV diagnosis. Patients were considered symptomatic if there were any symptom described by the doctor in the clinical chart. Patients who were symptomatic at first visit, without a defining opportunistic infection, pneumonia or chronic nonspecific diarrhea, were classified as patients with non-specific symptoms. The reasons to be tested for HIV were categorized as: doctor request, self request, testing in Voluntary Counseling and Testing sites (VCT), and other.

Statistical analyses

The categorical variables were expressed in terms of absolute and relative frequencies, and numerical variables were expressed as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR). Univariate and multivariate analyses for factors associated to LP and LPAD were performed. In univariate analysis, categorical data was compared using contingency tables and a Chi-Square test; numerical variables were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. Multivariate analysis was conducted using logistic regression models with backward manual elimination of variables.

Candidate variables for multivariate analysis were those that showed an association with LP and LPAD with a p-value ≤ 0.20 in the univariate analysis. To estimate the magnitude of the association between response variables and LP/LPAD, odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) was used. All p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Goodness of fit testing of logistic regression was assessed by Hosmer–Lemeshow test. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS software version 21 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

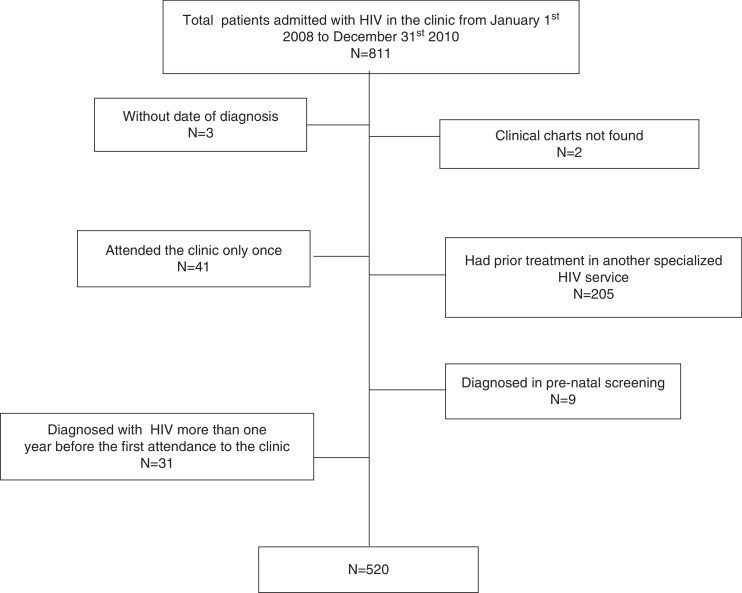

A total of 811 HIV infected patients were admitted to the clinic between January 1 2008 and December 31 2010. Five-hundred and twenty patients were eligible for the analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Diagram of the eligibility of patients for analysis in CTA–SAE. from 1 January 2008 to 31 December 2010.

The majority of patients included were men (77. 3%) with a median age of 35.1 years (IQR 28.1–44.6). The overall median CD4 cell count was 336 cells/mm3 (IQR: 130–531). It was greater among MSM (390 cells/mm3 IQR: 209–563) than in heterosexual women (338 cells/mm3 IQR: 130–531) and heterosexual men (225 cell/mm3 IQR: 58–444). Almost 70% of the patients had had at least eight years of education (n = 356–68.4%). At least 75% of them lived in Belo Horizonte city. Three-hundred and ninety seven patients (76. 3%) were employed. Two-hundred and forty-three patients (46.7%) self-reported as MSM and 159 (30.6%) self-reported as heterosexual. From 483 patients who provided information about their racial status, 51% declared themselves as white and 49% as non-white. CD4 cell count was available for 519 patients (99.8%). Those who did not have a CD4 count measurement, presented with an AIDS defining opportunist infection. Viral load measurements at first visit were available for 97% of the patients. The median VL for the whole cohort was 30,597 copies/ml (IQR: 9673–108,901). HBsAg, anti-HbC and anti-HCV were positive in 13 (2.5%), 123 (23.7%) and 15 (2.9%) patients, respectively.

Two-hundred and seventy-nine patients (53.7%) were classified as LP and 193 (37.1%) classified as LPAD. Despite having a CD4 thresholds higher than 350 cell/mm3 and 200 cells/mm3, eight and twenty patients met the LP and LPAD criteria, respectively, due to the diagnosis of an AIDS defining opportunistic infection. The characteristics of the cohort are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of newly diagnosed HIV patients at initiation of treatment in CTA–SAE from 2008 to 2010.

| Characteristics | N = 520 |

|---|---|

| Male n (%) | 402 (77.3) |

| Age (y), median (IQR) | 35.1 (28.1–44.6) |

| CD4 cell count, median (IQR) | 336 (130–531) |

| LP, n (%) | 279 (53.7) |

| LPAD, n (%) | 193 (37.1) |

| Level of education, n (%)a | |

| Illiterate | 13 (2.5) |

| <8 y | 147 (28.3) |

| 8–11 y | 230 (44.2) |

| >11 y | 126 (24.2) |

| HIV Risk Exposure, n (%) | |

| Heterosexual women | 118 (22.7) |

| Heterosexual men | 159 (30.6) |

| MSM | 243 (46.7) |

| Occupation, n (%)b | |

| Housewife | 21 (4.0) |

| Retired | 27 (5.2) |

| Unemployed | 32 (6.2) |

| Employed | 397 (76.3) |

| Student | 30 (5.8) |

| Race, n (%)c | |

| White | 247 (47.5) |

| Non-white | 236 (45.4) |

| Place of residence, n (%) | |

| Belo Horizonte | 404 (77.7) |

| Metropolitan area | 93 (17.9) |

| Other | 23 (4.4) |

| Reasons for the HIV test, n (%) | |

| Doctor request | 260 (50.0) |

| Patient request | 84 (16.2) |

| Voluntary Counseling and Testing sites | 67 (12.9) |

| Other | 109 (21.0) |

| Time between the diagnosis and first attendance (days), median (IQR) | 47 (28 –76.7) |

| Viral Load (copies/mL), median (IQR) | 30,597 (9672.5–108,901) |

| HBsAg positive, n (%)d | 13 (2.5) |

| Anti-HBc positive, n (%)e | 123 (23.7) |

| Anti-HCV positive, n (%)f | 15 (2.9) |

| VDRL positive, n (%)g | 81 (15.6) |

| Tuberculin skin test, n (%)h | |

| Negative (<5 mm) | 352 (67.7) |

| Positive (≥5 mm) | 39 (7.5) |

| Attending with symptoms, n (%) | 238 (45.8) |

| Non-specific symptoms | 184 (35.4) |

| Candida esophagitis | 48 (9.2) |

| Chronic nonspecific diarrhea | 44 (8.5) |

| Pneumonia | 30 (5.8) |

| Tuberculosis | 20 (3.8) |

| Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia | 17 (3.3) |

| Toxoplasma gondii encephalitis | 14 (2.7) |

| Interval in days between first attendance and ARV initiation, median (IQR) | 57.5 (27.8–430) |

| Year of first attendance, n (%) | |

| 2008 | 190 (36.5) |

| 2009 | 183 (35.2) |

| 2010 | 147 (28.3) |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range; LA, late presentation to care.

Missing data: n = 4 (0.8%).

Missing data: n = 13 (2.5%).

Missing data: n = 37 (7.1%).

Missing data:n = 19 (3.7%).

Missing data:n = 65 (12.5%).

Missing data:n = 16 (3.1%).

Missing data:n = 11 (2.1%).

Missing data:n = 129 (24.8%).

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the patients according to their baseline CD4 cell count measurement. LP and LPAD patients were significantly older than NLP patients, had a median age of 39.7 (IQR: 30.8–46.4), 41.2 (IQR: 33.9–47) and 31.8 (IQR: 25.8–41.5), respectively (p < 0.001). The proportion of MSM among LP and LPAD was 38.4% and 34.2%, respectively, whereas almost half of patients of the overall cohort and 56.4% of NLP were MSM. On the other hand, the proportion of heterosexual men was higher among LP and LPAD. The proportion of patients with more than 11 years of schooling in the NLP group was twice the proportion among LP and LPAD groups.

Table 2.

Comparison of new HIV patients at initiation of treatment in CTA–SAE from 2008–2010 according to their baseline CD4 cell count.

| Characteristics | NLP (n = 241; 46.3.1%) | LP (n = 279; 53.7%) | p-value¶ | LPAD (n = 193; 37.1%) | p-value§ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 186 (77.2) | 216 (77.4) | 0.948 | 149 (77.2) | 0.916 |

| Female, n % | 55 (22.8) | 63 (22.6) | 43 (22.8) | ||

| Age (y), median (IQR) | 31.8 (25.8–41.5) | 39.7 (30.8–46.4) | <0.001 | 41.2 (33.9–47.0) | < 0.001 |

| Age ≤35, n (%) | 154 (63.9) | 104 (37.3) | <0.001 | 54 (28.0) | < 0.001 |

| Level of education, n (%)a | <0.001 | < 0.001 | |||

| Illiterate | 2 (0.8) | 11 (4) | 8 (4.1) | ||

| <8 y | 49 (20.3) | 98 (35.1) | 79 (40.9) | ||

| 8–11 y | 108 (44.8) | 122 (43.7) | 75 (38.9) | ||

| >11 y | 79 (32.8) | 47 (16.8) | 31 (16.1) | ||

| HIV risk exposure, n (%) | <0.001 | < 0.001 | |||

| Heterosexual women | 55 (22.8) | 63 (22.6) | 44 (22.8) | ||

| Heterosexual men | 50 (20.8) | 109 (39.1) | 83 (43.0) | ||

| MSM | 136 (56.4) | 107 (38.4) | 66 (34.2) | ||

| Occupation, n (%)b | 0.047 | 0.012 | |||

| Housewife | 9 (3.7) | 12 (4.3) | 9 (4.7) | ||

| Retired | 10 (4.1) | 17 (6.1) | 13 (6.7) | ||

| Unemployed | 11 (4.6) | 21 (7.5) | 14 (7.3) | ||

| Employed | 183 (75.9) | 214 (76.7) | 152 (78.8) | ||

| Student | 21 (8.7) | 9 (3.2) | 3 (1.6) | ||

| Race, n (%)c | 0.005 | 0.004 | |||

| White | 132 (54.8) | 115 (41.2) | 76 (39.4) | ||

| Non-white | 96 (39.8) | 140 (50.2) | 99 (51.3) | ||

| Place of residence, n (%) | 0.179 | 0.170 | |||

| Belo Horizonte | 192 (79.7) | 212 (76.0) | 153 (79.3) | ||

| Metropolitan area | 43 (17.8) | 50 (17.9) | 28 (14.5) | ||

| Others | 6 (2.5) | 16 (5.7) | 11 (5.7) | ||

| Reasons for HIV test, n (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Doctor request | 76 (31.5) | 184 (66.0) | 142 (73.6) | ||

| Patient request | 56 (23.2) | 28 (10.0) | 19 (9.8) | ||

| Voluntary Counseling and Testing sites | 44 (18.3) | 23 (8.2) | 11 (5.7) | ||

| Others | 64 (26.1) | 44 (15.8) | 21 (10.9) | ||

| Time between the diagnosis and first attendance (days), median (IQR) | 54 (29.5–91.5) | 41 (27–65) | 0.005 | 40 (26–63.5) | 0.004 |

| Viral Load (copies/mL) median (IQR) | 15,600 (5314–29536) | 81,742 (26799–271788) | <0.001 | 116,180 (45463–353826) | <0.001 |

| HBsAg positive, n (%)d | 3 (1.2) | 10 (3.6) | 0.099 | 8 (4.1) | 0.069 |

| Anti-HBc positive, n (%)e | 48 (19.9) | 75 (26.9) | 0.060 | 58 (30.1) | 0.018 |

| Anti-HCV positive, n (%)f | 3 (1.2) | 12 (4.3) | 0.062 | 9 (4.7) | 0.039 |

| VDRL positive, n (%)g | 48 (19.9) | 33 (11.8) | 0.015 | 21 (10.9) | 0.012 |

| Tuberculin skin test, n (%)h | 0.831 | 0.976 | |||

| Negative (<5 mm) | 162 (67.2) | 190 (68.1) | 130 (67.4) | ||

| Positive (≥5 mm) | 23 (9.5) | 16 (5.7) | 10 (5.2) | ||

| Attend with symptoms, n (%) | 48 (19.9) | 190 (68.1) | <0.001 | 160 (82.9) | <0.001 |

| Interval in days between first attendance and ARV initiation, median (IQR) | 584 (306–848) | 35 (17–57) | <0.001 | 28 (12–43) | <0.001 |

| Year of first attendance, n (%) | 0.127 | 0.055 | |||

| 2008 | 77 (31.9) | 113 (40.5) | 83 (43.0) | ||

| 2009 | 92 (38.2) | 91 (32.6) | 59 (30.6) | ||

| 2010 | 72 (29.9) | 75 (26.9) | 51 (26.4) | ||

Abbreviations: NLP, not late presentation; LP, late presentation to care; LPAD late presentation with advanced disease; IQR, interquartile range; MSM, men who have sex with men; VCT, Voluntary Counseling and Testing sites.

Missing data: n = 3 (1.2%) – NLP; n = 1 (0.4%) – LP; n = 0 – LPAD.

Missing data: n = 7 (2.9%) – NLP; n = 6 (2.2%) – LP; N = 2 (1.0%) – LPAD.

Missing data: n = 13 (5.4%) – NLP; n = 24 (8.6%) – LA; N = 18 (9.3%) – LPAD.

Missing data: n = 11 (4.6%) – NLP; n = 8 (2.9) – LP; N = 4 (2.1) – LPAD.

Missing data:n = 24 (9.9%) – NLP; n = 41 (14.7) – LP; N = 29 (15.0) – LPAD.

Missing data:n = 10 (4.1%) – NLP; n = 6 (2.2) – LP; N = 5 (2.6) – LPAD.

Missing data: n = 7 (2.9%) – NLP; n = 4 (1.4) – LP; N = 4 (2.1) – LPAD.

Missing data: n = 56 (23.2%) – NLP; n = 73 (26.2) – LP; N = 53 (27.5) – LPAD.

p-value comparing NLP to LP.

p-value comparing NLP to LPAD.

Half of the patients in the cohort were tested for HIV because a doctor advised them to do so and this proportion increased in LP (66.0%) and LPAD (73.6%) groups and decreased among NLP (31.5%).

The median VL was almost six and eight fold higher among LP and LPAD, respectively, when compared to NLP. Co-infection with hepatitis B was higher in LP and LPAD groups than among NLP but without statistical significance (p = 0.099 for LP and p = 0.069 for LPAD). The proportion of positive HCV-antibody was higher in LP and LPAD groups but without statistical significance for LP (p = 0.06).

The median time between the diagnosis and the first visit to the treatment center was shorter in LP and LPAD groups than among NLP. The proportion of symptomatic patients at first visit was higher in LP (68.1%) and LPAD (82.9%) groups than in NLP (19.9%) group. The most reported AIDS defining opportunistic infections in LP and LPAD groups were Candida esophagitis (n = 48), Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia (n = 17), Toxoplasma gondii encephalitis (n = 14) and tuberculosis (n = 20). Non-AIDS defining conditions included chronic nonspecific diarrhea (n = 44), bacterial pneumonia (n = 24) and nonspecific symptoms (n = 142). In NLP group 48 patients reported symptoms at first visit; six had had a bacterial pneumonia and 42 nonspecific symptoms.

The results of univariate analysis using binary logistic regression to identify factors associated to LP and LPAD are shown in Table 3. Age over 35 years compared to those under 35; non-white compared to white; heterosexual men compared to HSH; high VL and being symptomatic at first visit compared to non-symptomatic patients were all associated with LP or LPAD.

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of factors associated with LP and LPAD of new HIV patients who initiate treatment in CTA–SAE 2008–2010.

| Variables | LP |

LPAD |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio | 95%IC | p-value | Odds ratio | 95%IC | p-value | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Female | 0.99 | 0.65–1.49 | 0.948 | 1.01 | 0.66–1.54 | 0.965 |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| <35 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| ≥35 | 2.98 | 2.08–4.26 | <0.001 | 4.27 | 2.90–6.28 | <0.001 |

| HIV risk exposure | ||||||

| Heterosexual women | 1.46 | 0.94–2.26 | 0.095 | 1.59 | 1.00–2.55 | 0.051 |

| Heterosexual men | 2.77 | 1.82–4.22 | <0.001 | 2.93 | 1.92–4.46 | 0.000 |

| MSM | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Level of education (years) | ||||||

| Illiterate | 2.75 | 0.59–12.89 | 0.415 | 1.38 | 0.43–4.41 | 0.590 |

| <8 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 8–11 | 0.56 | 0.37–0.87 | 0.009 | 0.42 | 0.27–0.64 | <0.001 |

| >11 | 0.30 | 0.18–0.49 | <0.001 | 0.28 | 0.17–0.47 | <0.001 |

| Occupation | ||||||

| Housewife | 3.11 | 0.97–9.97 | 0.056 | 6.75 | 1.55–29.45 | 0.011 |

| Retired | 3.97 | 1.31–11.97 | 0.014 | 8.36 | 2.04–34.29 | 0.003 |

| Unemployed | 4.45 | 1.53–12.97 | 0.006 | 7.00 | 1.76–27.89 | 0.006 |

| Employed | 2.73 | 1.22–6.11 | 0.015 | 5.58 | 1.67–18.72 | 0.005 |

| Students | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Race | ||||||

| White | 1.00 | |||||

| Non-white | 1.67 | 1.17–2.40 | 0.005 | 1.63 | 1.12–2.36 | 0.011 |

| Place of residence | ||||||

| Belo Horizonte | 1.00 | |||||

| Metropolitan area | 1.05 | 0.67–1.65 | 0.823 | 0.71 | 0.42–1.15 | 0.162 |

| Other cities | 2.42 | 0.93–6.30 | 0.071 | 1.64 | 0.69–3.88 | 0.259 |

| Reason for the HIV test | ||||||

| Doctor requirement | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Patient requirement | 0.21 | 0.12–0.35 | <0.001 | 0.24 | 0.14–0.43 | <0.001 |

| VCT | 0.22 | 0.12–0.38 | <0.001 | 0.16 | 0.08–0.33 | <0.001 |

| Other | 0.28 | 0.18–0.45 | <0.001 | 0.20 | 0.12–0.34 | <0.001 |

| Time between the diagnosis and the first attendance (in 10 days) | 0.97 | 0.94–1.00 | 0.040 | 0.97 | 0.94–1.01 | 0.117 |

| VL (in 10,000 units/ml) | 1.21 | 1.15–1.27 | <0.001 | 1.10 | 1.07–1.12 | <0.001 |

| Symptoms at first attendance | ||||||

| No | 1.00 | |||||

| Yes | 8.53 | 5.73–12.86 | <0.001 | 15.48 | 9.84–24.34 | <0.001 |

| Time between the diagnosis and the first attendance and ARV initiation (in 10 days) | 0.96 | 0.95–0.97 | <0.001 | 0.96 | 0.95–0.97 | <0.001 |

| Year of first attendance | ||||||

| 2008 | 1.00 | |||||

| 2009 | 0.68 | 0.46–1.02 | 0.061 | 0.62 | 0.41–0.93 | 0.021 |

| 2010 | 0.70 | 0.45–1.10 | 0.122 | 0.69 | 0.44–1.09 | 0.112 |

| VDRL | ||||||

| Negative | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Positive | 0.53 | 0.33–0.86 | 0.010 | 0.54 | 0.32–0.92 | 0.024 |

| HbsAg | ||||||

| Negative | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Positive | 0.53 | 0.33–0.86 | 0.109 | 2.76 | 0.89–8.57 | 0.079 |

| Anti-HCV | ||||||

| Negative | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Positive | 3.49 | 0.97–12.54 | 0.055 | 2.62 | 0.92–7.48 | 0.072 |

Abbreviations: LP, late presentation to care; LPAD, late presentation with advanced disease; IQR, interquartile range; MSM, men who have sex with men; VCT, Voluntary Counseling and Testing sites; VL, viral load; ARV, antiretroviral therapy; IC, interval of confidence.

Being retired, unemployed, or employed were all associated with LP and LPAD when compared to students. Being a housewife was associated to LPAD but not with LP. Protective factors were having completed more than eight years of schooling compared to less than eight years, not having done the HIV test because a doctor had requested and having a positive VDRL. Starting care in 2009 compared to starting care in 2008 was associated with less chance to be LPAD.

The factors associated with LP in the final multivariate logistic regression model were age, race, reasons to be tested for HIV, VL, symptoms at first visit, time between HIV diagnosis and the first visit, and VDRL (Table 4). Similarly, the predictive factors for LPAD were the same as for LP except race and reason to be tested for HIV. Factors associated with less LP were self request for being tested for HIV compared to doctor's request, and having a positive VDRL. Factors associated with less LPAD were living in the metropolitan area compared to living in Belo Horizonte, and having a positive VDRL. For A shorter interval between the first visit and ARV initiation were associated with both LP and LPAD.

Table 4.

Final Model of Multivariate Regression of factors associates with LP an LPAD of new HIV patients who initiate treatment in CTA–SAE 2008–2010.

| Variables | LPa |

LPADb |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio | 95%IC | p-value | Odds ratio | 95%IC | p-value | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| <35 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| ≥35 | 1.81 | 1.05–3.12 | 0.033 | 2.61 | 1.49–4.58 | <0.001 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 1.00 | |||||

| Non-white | 1.75 | 1.03–2.97 | 0.037 | |||

| Reasons for HIV test | ||||||

| Doctor request | 1.00 | |||||

| Self request | 0.44 | 0.20–0.97 | 0.043 | |||

| VCT | 0.47 | 0.22–1.02 | 0.057 | |||

| Others | 1.08 | 0.54–2.15 | 0.828 | |||

| Place of residence | ||||||

| Belo Horizonte | 1.00 | |||||

| Metropolitan area | 0.35 | 0.17–0.72 | 0.005 | |||

| Other cities | 0.79 | 0.22–2.87 | 0.717 | |||

| VL (in 10,000 units/ml) | 1.18 | 1.11–1.25 | <0.001 | 1.06 | 1.04–1.09 | <0.001 |

| Symptoms at first attendance | ||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Yes | 4.23 | 2.32–7.69 | <0.001 | 7.75 | 4.15–14.45 | <0.001 |

| Time between the diagnoses and the first attendance and ARV initiation (in 10 days) | 0.96 | 0.95–0.97 | <0.001 | 0.97 | 0.96–0.98 | <0.001 |

| VDRL | ||||||

| Negative | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Positive | 0.42 | 0.19–0.90 | 0.03 | 0.42 | 0.19–0.93 | 0.03 |

Abbreviations: VCT, Voluntary Counseling and Testing sites; VL, viral load; ARV, antiretroviral therapy; IC, interval of confidence.

Hosmer–Lemeshow χ2 = 9.97, DF = 8, p value 0.267.

Hosmer–Lemeshow χ2 = 7.47, DF = 8, p value 0.487.

Discussion

The proportion of LP (53.7%) and LPAD (37.1%) found in this study was significantly elevated. These rates are high, especially in Brazil, where a well recognized public health AIDS program is available for over 30 years.

These findings were higher than those reported by the Brazilian Health Ministry in recent years.11 Similar to other studies in Belo Horizonte city, 70% of the LP started care with CD4 cell count less than 200 cells/mm3.4, 9 The LPAD in this study was less frequent than reported previously in other Brazilian studies which ranged from 40.8% to 61%.3, 6

Compared to surveillance data for the whole HIV/AIDS Brazilian population, there was a higher proportion of male subjects as well as MSM in this cohort. Patients included in this cohort had higher educational levels than reported for the overall Brazilian population10, 11 and for Belo Horizonte in particular.4, 9 The proportion of each race did not differ from the national data.

In other limited-resource regions such as in African countries, the proportion of LP and LPAD are higher than that observed in this study with 70–80% presenting with advanced disease and 50–60% with CD4 count less than 350 cells/mm3.20, 21, 22 In Mexico as well as in Africa the proportion of LPAD was estimated to be 61%.23 The proportion of LP was similar to data from 35 countries in Europe,24 the United States of America (USA) and Canada.25

LP and LPAD patients were older and this is in accordance with the literature.3, 6, 13, 24, 25, 26 This population might have lower risk perception and be less educated that the younger generations. Being over 35 years was associated with LP (OR: 1.81 95%IC 1.05–3.12, p = 0. 033) and LPAD (OR: 2.61 95%IC 1.49–4.58, p = 0. 001).

The proportion of positive TST in the entire cohort was 7.5%. Although the proportion of positive TST was higher in the NLP group than in LP and LPAD groups there were no statistical difference (p = 0.831 and p = 0.976, respectively). This could be explained by the high proportion of missing TST results (24.8%).

As shown in the Brazilian surveillance data, sexual transmission is the main route of transmission as the IDU group was minimal.11

Gender was not associated with LP and LPAD. However, among patients self-reported as heterosexual, women presented earlier than men. Sixty-eight percent of heterosexual men were LP versus 53% of heterosexual women. This could be explained by the fact that Brazilian women take better care of their health than men, and seek health services for preventive exams more frequently.27 Heterosexual exposure, particularly among males, is widely correlated with late presentation and this could be explained by fewer opportunities to be tested, as they are not the main target of campaigns launched by the government as well as their own low risk perception.12, 13

Compared to students, being retired, unemployed or employed was associated with LP and LPAD in univariate analysis. Being a housewife was associated to LPAD but not with LP. These associations did hold in multivariate analysis. A possible explanation is the lower median age of the students (23 years IQR: 22–29) as compared to the median age of the other groups. Furthermore, the proportion of MSM among the students were expressive (83.3%).

MSM presented earlier to care than heterosexual men, according to univariate but not multivariate analyses, possibly because on average heterosexual patients were older than the MSM group. The median age of heterosexual women was 42 years (IQR: 33–49), 39 (IQR: 33–47) for heterosexual men, and 30 (IQR: 25–38) for MSM (p < 0.001). Even though MSM make up half the HIV infected population, they are infected at a lower age, perceive themselves at risk and get tested at an earlier stage, HIV prevention for this group remains a challenge.

In this study, the rates of HBsAg, anti-HBc and anti-HCV positive were lower than those reported for HIV/AIDS patients in Africa.20 However, these rates are four, six and two fold greater than the rates reported for the general Brazilian population.28 The fact that the hepatitis B virus has the same infection routes as HIV could explain this increased proportion. Therefore, it is important to reinforce hepatitis B vaccination in the population.

Non-whites was shown be at higher risk for LP in multivariate analysis. However, it should be pointed out that the mean educational level of non-whites was lower than in the white group. The proportion of non-whites with less than eight years of education was 60.2% versus 24% in the white group (p < 0.001). This fact is possibly related to disparities in access to health care, social economic conditions and access to education.

Living in the Belo Horizonte metropolitan area was a factor that reduced LPAD in multivariate analysis possibly because 60% of this population had their HIV test done for other reasons including blood donation. To be accepted, donors be healthy since they are screened by a doctor before the donation takes place.

It is difficult to compare the interval between diagnosis and treatment, since in many studies, the first CD4 cell measurement is considered as the start of care. In this study a median interval of 47 days (IQR: 28–77) was found for the overall population, which was lower among LP (41 days) and LPAD (40 days) than in NLP group (54 days) and correlates with the severity of the disease and the need to start ARV treatment immediately.

The proportion of patients who presented with clinical symptoms was high and it was associated with increased risk of LP and LPAD in multivariate regression. It is important to stress that 32% of LP and 18% of LPAD were asymptomatic at presentation in spite of having a high level of immune depletion. Therefore, it is important to reinforce CD4 cell measurement after diagnosis, whether the patient is symptomatic or not. Furthermore, a high proportion of patients had their HIV test done because of a doctor's referral in LP and LPAD groups. This must be analyzed with caution and could represent a low perception of risk and a low knowledge of the HIV disease.

Similar results were found in a study from Rio de Janeiro and Baltimore,5 where 75% of the studied population started treatment with VL > 10.000 copies/ml, which indicates a high potential for HIV transmission. As the impact of ARV and the decrease in VL are convincingly demonstrated and its impact in transmission is widely accepted29 the results of this study show the high risk of transmission by those subjects before they are diagnosed. In this way, enthusiasm for HIV treatment as a prevention measure to reduce transmission is unlikely to be accomplished unless early diagnosis is improved.

These findings are also relevant in clinical settings. Many guidelines30, 31 have recommended ARV initiation at higher CD4 cell counts, but this discussion is not applicable for the majority of new HIV patients since they present for treatment with CD4 thresholds below the recommended number.

A positive VDRL was associated with a lower chance of presenting late for treatment. In fact a person with an active symptomatic sexually transmitted disease (STD) might request a health service where early HIV testing is offered. It is noteworthy that 65% of the patients with positive VDRL were in the group of MSM, which reinforces the importance of prevention in this group. In this study only positive VDRL was considered and syphilis was not classified in clinical stages.

Although a lower risk of LP was noted in 2009 in univariate analysis, this did not hold true in the multivariate analysis. In fact, an increase in the median levels of CD4 cells was found in 2009 (377 cell/mm3 – IQR: 151–572) and 2010 (371 cells/mm3 – IQR: 164–530) compared to 2008 (272 cell/mm3 – IQR: 91–489). Nevertheless, the proportion of heterosexual males in 2008 was higher (36.8%) than in 2009 (29%) and 2010 (24.5%) and this could be considered as a confounding factor. This difference in the proportion of heterosexual men in these years could not be explained by the study.

This study has limitations. As a historical study from a single HIV cohort, they may not be representative of other national or international sites, though our analysis may provide insights applicable to such settings. Medical records with complete information were an important point of this study. The quality of data collected has led to a very few missing values.

In summary the results show that despite the availability of ARV free of charge in Brazil for more than 15 years and massive media campaigns encouraging HIV testing in the country, the proportion of patients starting treatment late is still high. These results suggest that recommendation for earlier treatment will have little impact in prevention unless effective strategies to increase universal HIV testing are implemented. Special focus should be placed on those who are not perceived to be or do not perceive themselves to be at risk for HIV infection, such as elderly people, non-whites, less educated people, and heterosexual men.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Levi G.C., Vitória M.A.A. Fighting against AIDS: the Brazilian experience. AIDS. 2002;16:2373–2383. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200212060-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marins J.R.P., Jamal L.F., Chen S.Y., Barros M.B., et al. Dramatic improvement in survival among adult Brazilian AIDS patients. AIDS. 2003;17:1675–1682. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200307250-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Souza-Jr P.R.B., Szwarcwald C.L., Castilho E.A. Delay in introducing antiretroviral therapy in patients infected by HIV in Brazil, 2003–2006. Clinics. 2007;62:579–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernandes J.R.M., Acúrcio F.A., Campos L.N., Guimarães M.D.C. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected patients with severe immunodeficiency in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais State, Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. 2009;25:1369–1380. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2009000600019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moreira R.I., Luz P.M., Struchiner C.J., et al. Immune status at presentation for HIV clinical care in Rio de Janeiro and Baltimore. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;57(Suppl. 3):S171–S178. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31821e9d59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pereira G.S., de Souza M.S., Caetano K.A., et al. Late HIV diagnosis and survival within 1 year following the first positive HIV test in a limited-resource region. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2011;22:313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oliveira M.T., Latorre M.R., Greco D.B. The impact of late diagnosis on the survival of patients following their first AIDS-related hospitalization in Belo Horizonte, Brazil. AIDS Care. 2012;24:635–641. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.630347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schechter M., Pacheco A.G. Late diagnosis of HIV infection in Brazil despite over 15 years of free and universal access to treatment. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2012;28:1541–1542. doi: 10.1089/AID.2012.0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ribeiro F.A., Tupinambás U., Fonseca M.O., Greco D.B. Durability of the first combined antiretroviral regimen in patients with AIDS at a reference center in Belo Horizonte Brazil, from 1996 to 2005. Braz J Infect Dis. 2012;16:27–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fonseca M.O., Tupinambás U., Souza A.I.A., Baisley K., Greco D.B., Rodrigues L. Profile of patients diagnosed with AIDS at age 60 and above in Brazil: from 1980 until June 2009, compared to those diagnosed at age18 to 59. Braz J Infect Dis. 2012;16:552–557. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de DST, AIDS e Hepatites Virais . 2013, December. Boletim Epidemiológico AIDS e DST, Brasília.http://www.AIDS.gov.br/publicacao/2013/boletim-epidemiologico-AIDS-e-dst-2013 [accessed 04.01.14] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Antinori A., Johnson M., Moreno S., Yazdanpanah Y., Rockstroh J.K. Report of a European Working Group on late presentation with HIV infection: recommendations and regional variation. Antivir Ther. 2010;15(Suppl. 1):31–35. doi: 10.3851/IMP1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adler A., Mounier-Jack S., Coker R.J. Late diagnosis of HIV in Europe: definitional and public health challenges. AIDS Care. 2009;21:284–293. doi: 10.1080/09540120802183537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mukolo A., Villegas R., Aliyu M., Wallston K.A. Predictors of late presentation for HIV diagnosis: a literature review and suggested way forward. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:5–30. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0097-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lesko C.R., Cole S.R., Zinsk A., Poole C., Mugavero M.J. A systematic review and meta-regression of temporal trends in adult CD4(+) cell count at presentation to HIV care, 1992–2011. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:1027–1037. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krentz H.B., Gill J. Despite CD4 cell count rebound the higher initial costs of medical care for HIV-infected patients persist 5 years after presentation with CD4 cell counts less than 350 μl. AIDS. 2010;24:2750–2753. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833f9e1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marks G., Crepaz N., Senterfitt J.W., Janssen R.S. Meta-analysis of high-risk sexual behavior in persons aware and unaware they are infected with HIV in the United States: implications for HIV prevention programs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39:446–453. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000151079.33935.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Center for Disease Control (U.S) 1993 Revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1992;41:961–962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Antinori A., Coenen T., Costagiola D., et al. Late presentation of HIV infection: a consensus definition. HIV Med. 2011;12:61–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2010.00857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agaba P.A., Meloni S., Sueli H., et al. Patients who present late to HIV care and associated risk factors in Nigeria. HIV Med. 2014;15:396–405. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Forbi J.C., Forbi T.D., Agwale S.M. Estimating the time period between infection and diagnosis based on CD4+ counts at first diagnosis among HIV-1 antiretroviral naïve patients in Nigeria. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2010;4:662–667. doi: 10.3855/jidc.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Admou B., Elharti E., Oumzil H., et al. Clinical and immunological status of a newly diagnosed HIV positive population, in Marrakech, Morocco. Afr Health Sci. 2010;10:325–331. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crabtree-Ramírez B., Caro-Vera Y., Belaunzarán-Zamudio F., Sierra-Madero J. High prevalence of late diagnosis of HIV in Mexico during the HAART era. Salud Publica Mex. 2012;54:506–514. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342012000500007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mocroft A., Lundgren J.D., Sabin M.L., et al. Risk factors and outcomes for late presentation for HIV-positive persons in Europe: results from the collaboration of observational HIV Epidemiological Research Europe Study (COHERE) PLoS ONE. 2013;10:e1001510. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Althoff K.N., Gange S.J., Klein M.B., et al. Late presentation for human immunodeficiency virus care in the United States and Canada. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:1512–1520. doi: 10.1086/652650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blanco J.R., Caro A.M., Pérez-Cachafeiro S., et al. HIV infection and aging. AIDS Rev. 2010;12:218–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brasil Ministério da Saúde Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Secretaria de Gestão Estratégica e Participativa . 2012. Vigitel Brasil 2007, Vigilância dos Fatores de Risco e Proteção para Doenças Crônicas por Inquérito Telefônico. Brasília. Available from: http://www.sbpt.org.br/downloads/arquivos/vigitel_2012.pdf. [accessed 22.05.14] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de DST, AIDS e Hepatites Virais . 2010. Estudo de Prevalência de Base Populacional das Infecções pelo Vírus das Hepatites A, B e C nas capitais do Brasil. Brasília. Available from: http://www.AIDS.gov.br/sites/default/files/anexos/publicacao/2010/50071/estudo_prevalencia_hepatites_pdf_26830.pdf [accessed 07.04.13] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen M.S., Chen Y.Q., McCauley M., et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de DST, AIDS e Hepatites Virais . 2013. Protocolo Clínico e Diretrizes Terapêuticas para Manejo da Infecção pelo HIV em Adultos. Brasília. Available from http://www.AIDS.gov.br/publicacao/2013/protocolo-clinico-e-diretrizes-terapeuticas-para manejo-da-infeccao-pelo-hiv-em-adul [accessed 02.12.13] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) 2013, February. Panel on antiretroviral guidelines for adults and adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. Available from: http://AIDSinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf [accessed 23.03.13] [Google Scholar]