Abstract

The hemoflagellate protozoan, Trypanosoma cruzi, mainly transmitted by triatomine insects through blood transfusion or from mother-to-child, causes Chagas’ disease. This is a serious parasitic disease that occurs in Latin America, with considerable social and economic impact. Nifurtimox and benznidazole, drugs indicated for treating infected persons, are effective in the acute phase, but poorly effective during the chronic phase. Therefore, it is extremely urgent to find innovative chemotherapeutic agents and/or effective vaccines. Since piplartine has several biological activities, including trypanocidal activity, the present study aimed to evaluate it on two T. cruzi strains proteome. Considerable changes in the expression of some important enzymes involved in parasite protection against oxidative stress, such as tryparedoxin peroxidase (TXNPx) and methionine sulfoxide reductase (MSR) was observed in both strains. These findings suggest that blocking the expression of the two enzymes could be potential targets for therapeutic studies.

Keywords: Trypanosomatids, Proteome, Piplartine, Therapeutic targets

Introduction

Chagas’ disease, caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, is an endemic illness in Latin America, mainly prevalent in Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Colombia, and Venezuela. The current treatment for Chagas’ disease is based on benznidazole and nifurtimox, which are effective against acute infections, but poorly effective during the chronic phase. In Brazil, nifurtimox had its production and use discontinued. In this context, major efforts are necessary to identify new targets and develop novel trypanocidal drugs.1, 2, 3, 4, 5

Phytochemical studies of Piper species have led to the isolation of typical classes of secondary metabolites such as amides, terpenes, benzoic acid derivatives, and hydroquinones, lignans, neolignans, and flavonoids.6, 7, 8, 9 Piplartine (Fig. 1) is an amide isolated from Piper species. An excellent review described its biological activities,10 such as cytotoxic, genotoxic, antitumor, antiangiogenic, antimetastatic, antiplatelet aggregation, antinociceptive, anxiolytic, antidepressant, anti-atherosclerotic, antidiabetic, antibacterial, antifungal, leishmanicidal, trypanocidal, schistosomicidal, and larvicidal activities.11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 Administration of piplartine inhibited solid tumor development in mice transplanted with Sarcoma 180 cells and histopathological analysis showed that liver and kidneys of treated animals were only slightly and reversibly affected.20 Anticancer activity of piplartine was reinforced when it reduced human glioblastoma (SF-295) and colon carcinoma (HCT-8) cell viability.21 Acute toxicity studies performed in rats and mice treated with different piplartine doses by oral route demonstrated no obvious clinical alterations.22 Viability assay carried out against T. cruzi epimastigote forms demonstrated growth inhibition higher than that observed with benznidazole,23 and activity against Leishmania donovani was observed, with considerable reduction in parasitic burden and spleen weight in vivo.24

Fig. 1.

Chemical structure of piplartine.

The low systemic cytotoxicity of piplartine associated with activity against trypanosome cells brought new questions about the possibility of its use as a trypanocidal drug. Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate protein expression changes in response to piplartine treatment on the epimastigote form of T. cruzi. The capacity of the parasite to grow, associated to high level of cells obtained, allow for performing differential proteomic and mass spectrometry assays. The obtained results are consistent with those described in the literature and may contribute with future similar analysis using other forms of T. cruzi.

In this paper, two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2-DE) and mass spectrometry were used to identify different expressed proteins as a result of piplartine effect on two T. cruzi strains, Y25 and Bolivia,26 respectively.

Materials and methods

Piplartine isolation

Isolation of piplartine from Piper tuberculatum leaves was carried out according to a methodology previously published.23 Briefly, specimens of Piper tuberculatum were cultivated from seeds under greenhouse conditions at the Institute of Chemistry, Universidade Estadual Paulista, Araraquara, São Paulo State, Brazil. Plant material was collected in May 2005 and identified by Dr. Guillermo E. D. Paredes from Universidad Pedro Ruiz Gallo, Kambayeque, Peru. Voucher (Cordeiro-1936) was deposited at the herbarium of the Institute of Biosciences, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, São Paulo State, Brazil.

Shade-dried and powdered leaves of P. tuberculatum (200 g) were extracted with ethyl acetate (Synth) and methanol (Synth) (9:1), for three weeks at room temperature. After filtering, the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure to yield crude extract (11 g). Crude extract (10 g) was subjected to chromatography column over silica gel 60 (70–230 mesh, Merck) and eluted with hexane (Synth) and ethyl acetate (Synth) (0–100% ethyl acetate), and ethyl acetate (Synth) and methanol (Synth) (0–100% methanol) to afford 12 fractions (E1–E12). Fractions E6 and E7 (2.17 g) was further purified by chromatography column over silica gel 60 (70–230 mesh, Merck) and eluted with hexane (Synth) and acetone (Synth) (9:1) to provide 21 fractions (F1–F21), including piplartine (fraction F11, 532 mg). Structure of piplartine was identified by 1H and 13C NMR spectra analysis.

Trypanosoma cruzi cell viability assay

Epimastigote forms (Y and Bolivia strains) were maintained in Liver Infusion Tryptose (LIT) medium (68.4 mM NaCl; 5.4 mM KCl; 56.3 mM Na2HPO4; 111 mM Dextrose; 0.3% Liver Infusion Broth; 0.5% Tryptose)27 and the cells were harvested during the exponential growth phase. The parasites (1 × 107 cells/mL) were treated for 48 h in LIT at 28 °C with 13.7 μM (Y strain) and 10.5 μM (Bolivia strain) piplartine, which corresponds to half of IC50/72 h previously determined for this compound. Triplicates of treated and control (without piplartine) parasites were prepared. Calculated IC50 in 72 h of experiment for piplartine in Y and Bolivia strains were 27.45 μM and 20.95 μM, respectively. For Balb/c macrophages IC50 was 305.79 μM. Safety index was 11.14 and 14.59, in comparison with piplartine IC50 for Y and Bolivia strains, respectively (data not published). The chosen concentration of the piplartine for 2DE-DIGE tests was half the IC50 previously determined, since the intention was to induce protein expression changes, maintained considerable number of viable parasites.

Sample preparation, labeling and two-dimensional electrophoresis

Treated and control epimastigotes parasites from both strains were centrifuged at 3000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C, the pellet was washed three times with tryps wash buffer (100 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 20 mM Tris–Hcl, pH 7.5) and incubated in lysis buffer (7 M Urea, 2 M Thiourea, 4% CHAPS, 40 mM Tris, 0.1 mg/mL PMSF; 1 M DTT, 1 mg/mL Pepstatin, 10 mg/mL Aprotinin and 10 mg/mL Leupeptin; all enzyme inhibitors from Sigma-Aldrich) for two hours. Protein extraction was performed using three independent biological replicates of each sample (treated and control). To obtain the soluble protein fraction, the cell lysate was centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C and the protein content was determined using the Bradford method.

Each fraction (50 μg of protein of control and of treated triplicates) was marked with DIGE Kit (GE Healthcare) according Table 1. Briefly: DIGE uses direct labeling of proteins with fluorescent dyes (known as CyDyes: Cy2, Cy3, and Cy5) prior to IEF (isoelectric focusing). Dye concentrations are kept low, such that approximately one dye molecule is added per protein. The important aspect of the DIGE technology is its ability to label two or more samples with different dyes and separate them on the same gel, eliminating gel-to-gel variability. This makes spot matching and quantitation much simpler and more accurate. Cy2 is used for a normalization pool created from a mixture of all samples in the experiment. This Cy2-labeled pool (50 μg of protein of all samples applied in the experiment-control and treated triplicates) is run on all gels, allowing spot matching and normalization of signals from different gels.28, 29, 30, 31, 32 The label proteins were then solubilized in the DeStreak following the manufacturer instructions (GE Healthcare). Each strip was rehydrated with the sample solution for 20 h at room temperature and the proteins were separated over immobilized linear pH 3–10 gradients (IPGphor system, GE Heathcare) using the following protocol: 200 V/12 h, 1000 V/1000 Vh, 8000 V/8000 Vh, 8000 V/20,000 Vh. The pH wide range was applied to obtain the largest number of protein differential expression. The strips were incubated for 15 min in 5 mL of equilibrate buffer (6 M uréia, 50 mM Tris–Hcl 1.5 M, pH 8.8, 30% glicerol, 2% SDS, 1% bromophenol blue) containing 50 mg DTT, followed by a second incubation for 15 min in 5 mL of the same buffer containing 125 mg iodoacetamide.

Table 1.

Sample schematic labeling with Cy Dye DIGE kit.

| Labeling samples | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| GEL 1 | Pool (50 μg of proteins + 1 μL of Cy2) | Control 1 (50 μg of proteins + 1 μL of Cy3) | Treated 1 (50 μg of proteins + 1 μL of Cy5) |

| GEL 2 | Pool (50 μg of proteins + 1 μL of Cy2) | Control 2 (50 μg of proteins + 1 μL of Cy5) | Treated 2 (50 μg of proteins + 1 μL of Cy3) |

| GEL 3 | Pool (50 μg of proteins + 1 μL of Cy2) | Control 3 (50 μg of proteins + 1 μL of Cy3) | Treated 3 (50 μg of proteins + 1 μL of Cy5) |

| GEL 4 | Preparative (gel to cut the spots) (500 μg of proteins of all samples applied in the experiment-control and treated triplicates) | ||

Second dimension separation was performed by 12.5% SDS-PAGE polyacrylamide gels. Gels were run in a SE 600 Ruby (GE Healthcare) at 10 mA/gel for 45 min and then at 30 mA/gel until the end of the gel was reached and 100 W and 600 V. Molecular mass markers were prepared according to the instructions of manufacturer (GE Healthcare) and applied to filter paper before positioning the strips. The gels were scanned in Typhoon Variable Mode (GE Healthcare) and detected spots were quantified and analyzed with the Image Master Platinum software (GE Healthcare). The differential expression analysis was performed comparing the treated and control groups by the Student's t test (>1.3 fold and p ≤ 0.05). The cut-off limit employed was based on statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05).

Preparative gels (containing 500 μg of protein of control and treated triplicates) were stained with Coomassie colloidal as follows: fixation in 45% v/v ethanol and 10% v/v acetic acid for 15 min, washed in deionized water and the addition of 0.1% w/v Coomassie brilliant blue G (Sigma-Aldrich) overnight. The gels were destained with 40% v/v ethanol and 10% v/v acetic acid until visualization of spots. Ten spots were manually excised from preparative gel, being five spots, which protein were more expressed than control, and five spots which treated presented more expression.

Gel in situ trypsin digestion and mass spectrometry analysis

The gel spots corresponding to tagged-protein were excised and destained with 50% acetonitrile/0.1 M ammonium bicarbonate pH 8.0. Gels were dehydrated with neat acetonitrile and vacuum dried for 30 min. Gels were swollen with 0.5 μg of modify trypsin (Promega) in 20 μL of 0.1 M ammonium bicarbonate pH 8.0, and the gels were covered by adding 100 μL of 0.1 M ammonium bicarbonate pH 8.0 for 22 h at 37 °C. Trypsin hydrolysis was stopped with 5 μL of formic acid. The tryptic peptides were extracted and desalted in microtip filled with POROS 50 R2 (PerSeptive Biosystems) previously equilibrated in 0.2% formic acid and eluted with 60% methanol/5% formic acid for mass spectrometry analysis. Samples were diluted in matrix CHCA 5 mg/mL (alfa-cyano-4-hydroxicinnamic acid, Sigma) with 50% acetonitrile/0.1% TFA (trifluoroacetic acid) and 2–3 μL were deposited on MALDI plates using drop dried method. Mass spectrometry analysis was performed in MALDI-TOF/TOF (AXIMA performance, Kratos-Shimadzu) and the MS/MS spectra of tryptic peptides were submitted directly to MASCOT program against the NCBInr and local trypanosomatids databases.

Results

Several T. cruzi proteomic studies have been performed to generate 2DE protein maps of different life cycle stages, to study development-induced changes, identify proteins involved in drug resistance and effects of trypanocidal agents.33, 34, 35, 36

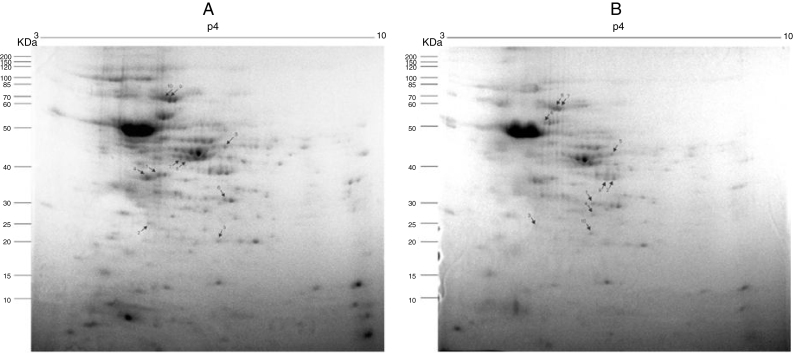

Fig. 2A and B, from Y and Bolivia strains, respectively, show the 10 protein spots differently overexpressed in the cells, being five spots in control (Table 2, Table 3, column “control”, spots 1–5), and five spots in treated condition (Table 2, Table 3, column “treated”, spots 6–10).

Fig. 2.

Preparative 2-DE gel image of T. cruzi (A. Y strain; B. Bolivia strain) treated with piplartine from P. tuberculatum and control. IEF was performed with 500 μg of soluble protein from the parasites using 13 cm strips with a pH range of 3–10. SDS-PAGE was performed with 12.5% polyacrylamide gels, which were stained with Colloidal Coomassie Blue. Arrows indicate modulated proteins of controls and after treatment with the compound; numbers refer to spot identification in Table 1, Table 2, respectively.

Table 2.

T. cruzi (Y strain) protein identification in control and treated parasites with piplartine.

| Spot | X-fold differential expression |

NCBI |

MASCOT |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Treated | Protein | Access number | Peptides | Mass (Da) | Score | pI | Amino acid sequence cover (%) | |

| 1 | +2.111 | Cytochrome C oxidase subunit IV | gi|71660419 | FTGEPPSWMR ACTDLNQLEEWSR |

39,119 | 123 | 5.72 | 6.90 | |

| 2 | +2.194 | Tryparedoxin peroxidase | gi|71408703 | ANEYFEK EAAPEWAGK VVQAFQYVDK HITVNDLPVGR DYGVLIEEQGISLR |

25,734 | 338 | 5.96 | 22.60 | |

| 3 | +2.349 | Tryparedoxin peroxidase | gi|17224953 | QITVNDLPVGR SYGVLKEEDGVAYR HGEVCPANWKPGDK |

22,660 | 183 | 5.96 | 19.60 | |

| 4 | +2.483 | Beta-tubulin | gi|1220547 | LREEYPDR LAVNLVPFPR FPGQLNSDLR KLAVNLVPFPR FPGQLNSDLRK INVYFDEATGGR AVLIDLEPGTMDSVR AVLIDLEPGTMDSVR GHYTEGAELIDSVLDVR |

50,126 | 513 | 4.74 | 16.70 | |

| 5 | +2.853 | Cystathionine beta-synthase | gi|71404306 | GYVLLDQYR SADKESFALASEVHR AHYEGTAQEIYDQCGK |

47,830 | 308 | 6.43 | 9.60 | |

| 6 | +1.890 | Methylthioadenosine phosphorylase | gi|71655964 | VGGVDCAFLPR TFPGLAAGTEGWR HGVGHVLNPSEVNYR LHEQGTSVTMEGPQFSTK LHEQGTSVTMEGPQFSTK YYAIETPFGRPSGDICVK |

33,523 | 456 | 6.34 | 24.80 | |

| 7 | +1.951 | Prostaglandin F2α synthase | gi|25006239 | YDFEEADQQIR ETYGVPEELTDDEVR AQQNWPLNEPRPETYR |

42489 | 235 | 5.83 | 11.60 | |

| 8 | +1.962 | Prostaglandin F2α synthase | gi|25006239 | FIANPDLVER YDFEEADQQIR KIEPLSLAYLHYLR ETYGVPEELTDDEVR AQQNWPLNEPRPETYR |

42,489 | 391 | 5.83 | 17.90 | |

| 9 | +1.982 | Heat shock 70 kDa protein, mitochondrial precursor | gi|71407515 | DAGTIAGLNVIR EISEVVLVGGMTR EISEVVLVGGMTR RFEDSNIQHDIK KVSNAVVTCPAYFNDAQR |

71,503 | 242 | 5.75 | 8.40 | |

| 10 | +2.024 | 70 kDa heat shock protein | gi|119394467 | FEELCGDLFR AVHDVVLVGGSTR TTPSYVAFTDTER |

72,428 | 238 | 5.37 | 5.40 | |

Table 3.

T. cruzi (Bolivia strain) protein identification in control and treated parasites with piplartine.

| Spot | X-fold differential expression |

NCBI |

MASCOT |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Treated | Protein | Access number | Peptides | Mass (Da) | Score | pI | Amino acid sequence cover (%) | |

| 1 | +1.310 | Tryparedoxin peroxidase | gi|17224953 | QITVNDLPVGR SYGVLKEEDGVAYR HGEVCPANWKPGDK |

22,660 | 219 | 5.96 | 19.60 | |

| 2 | +1.796 | Methylthioadenosine phosphorylase | gi|71655964 | VGGVDCAFLPR TFPGLAAGTEGWR HGVGHVLNPSEVNYR YYAIETPFGRPSGDICVAK |

33,523 | 398 | 6.34 | 18.90 | |

| 3 | +1.928 | D-isomer specific 2-hydroxyacid dehydrogenase-protein | gi|71420052 | EVDEYGVR TANLVPDSVR FIGLVNEYAK TANLVPDSVRR RLDTYLVDPVR GITQNEDDLACALR ESDFVVNILPGTEETKR |

38,795 | 479 | 6.04 | 20.90 | |

| 4 | +1.982 | Tryparedoxin peroxidase | gi|17224953 | QITVNDLPVGR SYGVLKEEDGVAYR HGEVCPANWKPGDK |

22,660 | 221 | 5.96 | 19.60 | |

| 5 | +2.144 | Cystathionine beta-synthase | gi|71404306 | GYVLLDQYR SADKESFALASEVHR AHYEGTAQEIYDQCGGK TETALPWDHPDSLIGMAR |

47,830 | 421 | 6.43 | 13.80 | |

| 6 | +1.529 | Chaperonin HSP60, mitochondrial protein | gi|3023478 | NVIIEQSYGAPK GLIDGETSDYNR GYISPYFVTDAK AVGVILQSVAEQSR YVNMFEAGIIDPAR AAVQEGIVPGGGVALLR ALDSLLGDSSLTADQR VLENNDVTVGYDAQR KVTSTENIVQVATISANGDEELGR |

59,639 | 801 | 5.38 | 24.20 | |

| 7 | +1.544 | Heat shock 70 kDa protein, mitochondrial precursor | gi|71407515 | EISEVVLVGGMTR RFEDSNIQHDIK KVSNAVVTCPAYFNDAQR |

71,503 | 184 | 5.75 | 6.60 | |

| 8 | +1.683 | Heat shock protein 70 | gi|10626 | TTPSYVAFTDTER ARFEELCGDLFR AVVTVPAYFNDSQR DCHLLGTFDLSGIPPAPR SQIFSTYADNQPGVHIQVFEGER |

74,564 | 437 | 5.64 | 11.80 | |

| 9 | +1.864 | Methylthioadenosine phosphorylase | gi|71655964 | VGGVDCAFLPR TFPGLAAGTEGWR HGVGHVLNPSEVNYR LHEQGTSVTMEGPQFSTK YYAIETPFGRPSGDICVAK |

33,523 | 516 | 6.34 | 24.80 | |

| 10 | +2.570 | Peptide methionine sulfoxide reductase | gi|71405176 | IHDPTTVNR QGVDVGTQYR AFGDAQVVTSLEK SAIFYHDDQQLK LHVAEDYHQMYLEK LHVAEDYHQMYLEK |

20,204 | 386 | 6.12 | 32.80 | |

The differential approach using T. cruzi cells demonstrated tryparedoxin peroxidase, involved in oxidative stress response, had important decreased expression in treated (that is, more expressed in control), as showed in Table 2, Table 3. It was possible to observe two spots differential expressed by Y strain, with reduction of 2.194 and 2.349 folds (Table 2, spots 2 and 3); and two spots by Bolivia strain, with reduction of 1.310 and 1.982 folds (Table 3, spots 1 and 4).

Methylthioadenosine phosphorylase (MTAP, Table 2, spot 6 and Table 3, spot 2) catalyzes the reversible phosphorolytic cleavage of methylthioadenosine, a by-product of the polyamine biosynthesis, producing methylthioribose-1-phosphate (MTRP) and adenine.37 Interesting, in the Bolivia strain, MTAP was identified in spots 2 and 9, one overexpressed (spot 9) and the other (spot 2) representing reduction of the expression. In Fig. 2B, it is possible to observe that these spots presented small shift in gel and should represent a post-translation modification, suggesting that this mechanism can regulate the expression of this member.

Some studies demonstrated the interaction between tryparedoxin and cystathionine γ-lyase (CGL),38 although the enzyme found in our experiment was cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) (Table 2, Table 3, spots 5). Previous studies in mammal cells demonstrated that CBS and CGL act in the same pathway and are primarily responsible for hydrogen sulfide biogenesis.39

Enzyme D-isomer specific 2-hydroxyacid dehydrogenase, whose expression levels was altered only in the Bolivia strain (Table 3, spot 3), was one of the proteins identified in the present work This enzyme is responsible to catalyze the NAD-dependent oxidation of R-lactate to pyruvate and is part of the detoxification pathway of methylglyoxal (dependent of glyoxalase I, glyoxalase II and low molecular mass thiols) in trypanosomatids, and data from Trypanosoma conorhini and Crithidia fasciculata showed activation in the presence of cysteine.40 Altogether, these data strongly suggest a redox regulation of this enzyme in trypanosomatids.

Other protein overexpressed only in the Bolivia strain treated with piplartine was methionine sulfoxide reductase (MSR, Table 3, spot 10). Several amino acid residues were susceptible to oxidation such as cysteine, histidine, tryptophan, tyrosine and methionine.

Proteomics studies usually identified proteins highly expressed such as chaperones, structural and ribosomal proteins and others. In the present work, it was possible to observe heat shock protein 70 and tubulin differentially expressed (Table 2, Table 3).

Discussion

Various articles explored the activity of different compounds against Y and Bolivia Trypanosoma cruzi strains, in special comparing benzinidazole activity. Alves and collaborators found higher IC50 of benzinidazole for Y (11.77 μg/mL) compared to Bolivia (0.99 μg/mL) strain. The natural extracts tested showed moderate activity against Bolivia strains, while in Y strain there was satisfactory activity.41 In other studies, Bolivia strain proved to be more resistant to beniznidazole than Y strain. Kohatsu and collaborators observed an IC50 almost three times higher in Bolivia than in Y strain and demonstrated that this compound increased the expression of the mitochondrial tryparedoxin peroxidase only in Y strain.42 Additionally, Bolivia strain was more resistant to treatment of two nitrofurans derivatives (NF and NFOH-121) when compared to Y strain. Also, no changes at mRNA processing levels in the Bolivia strain was observed.43 Mice infected with Y and Bolivia strains treated with benzinidazole demonstrated remarkable differences in mortality rates. All groups infected with the Y strain (treated and non-treated) presented 100% survival. However, only 60% survival was observed in the group infected with the Bolivia strain, while non-treated mice had 100% survival. These findings indicated that treatment with benzinidazole could be detrimental to animals infected with the Bolivia strain.44 Altogether, these results reinforce that wide genetic heterogeneity of T. cruzi strains affect the response against trypanocidal compounds. Our findings showed similar proteome variations in both strains, altering the expression of proteins involved in oxidative stress response. In other hands, two proteins presented protein expression variations only in the Bolivia strain, D-isomer specific 2-hydroxyacid dehydrogenase and methionine sulfoxide reductase.

Raj and co-workers22 identified 12 potential piplartine targets using differential proteomics approach on two human cell lines, bladder carcinoma and osteosarcoma. Interestingly, these authors identified various proteins involved in stress oxidative response such as glutathione S-transferases and peroxiredoxin. In addition, it was found that piplartine can interact directly with purified recombinant glutathione S-transferase p1 (GSTp1), inhibiting the enzyme activity and decreasing the levels of reduced glutathione. These actions led to increase of oxidized glutathione levels in tumor cells. These data suggest that piplartine can interact directly with components of the oxidative stress response in trypanosomatids cells. Tryparedoxin peroxidase presents crucial role in the regulation of the parasite ROS levels and it is important to highlight the importance of this enzyme as Chagas’ disease drug target.45

Mitochondrial and cytosolic tryparedoxin peroxidase detoxify peroxynitrite, hydrogen peroxide and small hydroperoxide organic compounds. Ascorbate heme-dependent peroxidase occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum and presents action against hydrogen peroxide. Other enzymes that act against oxidizing agents are the superoxide dismutases (SOD) occurring in the cytosol, mitochondria and glicosoma and work in the detoxification of superoxide.46

The main results obtained could be explained by potential interaction among tryparedoxin peroxidase and several other proteins, which are differentially expressed and identified. Piñeyro and co-workers38 using proteomic approaches described potential interactions between tryparedoxin 1 (TcTXN1) and tryparedoxin peroxidase in vitro and in vivo. Methylthioadenosine phosphorylase (MTAP) is responsible to catalyze the reversible phosphorolytic cleavage of methylthioadenosine, a polyamine biosynthesis subproduct, producing methylthioribose-1-phosphate (MTRP) and adenine. In mammal cells, MTAP is redox regulated and can be inactivated by specific oxidation of two conserved cysteines to sulfenic acid, and it should be pointed out that these amino acids were conserved in T. cruzi protein.35

Therefore, two hypotheses for the difference in MTAP expression following piplartine treatment can be postulated: first, the direct interaction between tryparedoxin and tryparedoxin peroxidase was affected, modifying MTAP levels. These results suggest a secondary role of piplartine in polyamines metabolism. Secondly, redox unbalancing caused for tryparedoxin peroxidase change the expression of MTAP. Since for the Bolivia strain two different spots (2 and 9) were identified, one overexpressed (spot 9) and other (spot 2) with down-expression, and these spots presented little shift in gel probably representing a post-translation modification. This mechanism could regulate the expression of this enzyme.

T. cruzi appears to be the first protist proven to have two independent pathways for cysteine production; sulfur-assimilation from sulfate and transsulfuration from methionine via cystathionine. Extracellular l-cysteine, but not l-cystine, has been shown to be essential for growth of the T. brucei bloodstream form. Trypanosomes require cysteine not only for protein biosynthesis, but also for formation of trypanothione and glutathione. They may require multiple cysteine acquiring pathways to ensure this amino acid is available to fulfill the needs of their redox metabolism.38 Therefore, it is possible to correlate tryparedoxin peroxidase, cystathionine beta-synthase and redox balance. Recently, the same interactome approach was used to demonstrate the partners of T. cruzi tryparedoxin II.40

Oxidation of methionine to methionine sulfoxide affects the biological function of oxidized proteins.47 Consequently, the occurrence of a system for reducing methionine sulfoxide to methionine is important for cell integrity and its reaction is present in virtually all organisms.48, 49 Therefore, the presence of a system for reducing methionine sulfoxide to methionine guarantees cell integrity and is present in virtually all organisms.38, 50 Methionine sulfoxide reductase (MSR) protects the organism from oxidative stress and is involved with resistance against biotic and abiotic stress in plants and animals.38, 51 Arias and co-authors52 studied MSR production in T. cruzi and T. brucei, indicating a crucial function of this enzyme in the redox metabolism in trypanosomatids and could help the parasites to face oxidative stress. This enzyme is not directly involved in the removal of oxidizing agents, but act mainly in repairing oxidized proteins, maintaining cellular functionality. They found that the reversal of the oxidized state of MSR recombinant is dependent on the presence of reduced tryparedoxin (TXN), probably reducing substrate of the MSR.52

Conclusion

The oxidative stress response is an important defense of T. cruzi against the host immune system and other mechanisms of parasite clearance. Therefore, activity molecules able to interfere in this parasitic metabolism represent a potential therapeutic target in Chagas’ disease. The DIGE technology eliminating gel-to-gel variability improved the obtention of protein spots. Altogether, our results suggested that piplartine activity in trypanosomes promoted imbalance of some important enzymes related to redox metabolism in these parasites. It should be further investigated whether these enzymes could serve as potential biomarkers to evaluate disease treatment.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: FAPESP (2007/02076-3; 2007/56140-4; 2011/24017-4) CAPES and PADC (Proc. 2018/02-II).

Contributor Information

Marco Túlio Alves da Silva, Email: silvamta@gmail.com.

Regina Maria Barretto Cicarelli, Email: cicarell@fcfar.unesp.br.

References

- 1.Souza W. From the cell biology to the development of new chemotherapeutic approaches against trypanosomatids: dreams and reality. Kinetoplastid Biol Dis. 2002;1:1–21. doi: 10.1186/1475-9292-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soeiro M.N., de Castro S.L. Trypanosoma cruzi targets for new chemotherapeutic approaches. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2009;13:105–121. doi: 10.1517/14728220802623881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Urbina J.A. New insights in Chagas’ disease treatment. Drugs Future. 2010;35:409–419. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Urbina J.A. Specific chemotherapy of Chagas disease: relevance, current limitations and new approaches. Acta Trop. 2010;115:55–68. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grael C.F.F., Albuquerque S., Lopes J.L.C. Chemical constituents of Lychnophora pohlii and trypanocidal activity of crude plant extracts and of isolated compounds. Fitoterapia. 2005;76:73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lago J.H.G., Ramos C.S., Casanova D.C.C., et al. Benzoic acid derivatives from Piper species and their fungitoxic activity against Cladosporium cladosporioides and C. sphaerospermum. J Nat Prod. 2004;67:1783–1788. doi: 10.1021/np030530j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Navickiene H.M.D., Alécio A.C., Kato M.J., et al. Antifungal amides from Piper hispidum and Piper tuberculatum. Phytochemistry. 2000;55:621–626. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00226-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Navickiene H.M.D., Morandim A.A., Alécio A.C., et al. Composition and antifungal activity of essential oil from Piper aduncum, Piper arboretum and Piper tuberculatum. Quím Nova. 2006;29:467–470. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Regasini L.O., Cotinguiba F., Siqueira J.R., Bolzani V.S., Silva D.H.S., Furlan M. Radical scavenging capacity of Piper arboreum and Piper tuberculatum (Piperaceae) Lat Am J Pharm. 2008;27:900–903. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bezerra D.P., Pessoa C., de Moraes M.O., Saker-Neto N., Silveira E.R., Costa-Lotufo L.V. Overview of the therapeutic potential of piplartine (piperlongumine) Eur J Pharm Sci. 2013;48:453–463. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barbosa-Filho J.M., Piuvezam M.R., Moura M.D., et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of alkaloids: a twenty century review. Rev Bras Farmacogn. 2006;16:109–139. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakamura C.V., Santos A.O., Vendrametto M.C., et al. Atividade antileishmania do extrato hidroalcoólico e de frações obtidas de folhas de Piper regnellii (Miq.) C. DC. Var. Pallescens (C. DC.) Yunck Rev Bras Farmacogn. 2006;16:61–66. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amorim M.F.D., Diniz M.F.F.M., Araújo M.S.T., et al. The controvertible role of kava (Piper methysticum G. Foster), an anxiolytic herb, on toxic hepatitis. Rev Bras Farmacogn. 2007;17:448–454. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saúde-Guimarães D.A., Faria A.R. Substâncias da natureza com atividade anti-Trypanosoma cruzi. Rev Bras Farmacogn. 2007;17:455–465. [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Moraes J., Nascimento C., Lopes P.O., et al. Schistosoma mansoni: in vitro schistosomicidal activity of piplartine. Exp Parasitol. 2011;127:357–364. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2010.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quintans-Júnior L.J., Almeida J.R.G.S., Lima J.T., et al. Plants with anticonvulsant properties – a review. Rev Bras Farmacogn. 2008;18:798–819. [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Moraes J., Nascimento C., Yamaguchi L.F., Kato M.J., Nakano E. Schistosoma mansoni: in vitro schistosomicidal activity and tegumental alterations induced by piplartine on schistosomula. Exp Parasitol. 2012;32:222–227. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Araújo-Vilges K.M., Oliveira S.V., Couto S.C.P., et al. Effect of piplartine and cinnamides on Leishmania amazonensis, Plasmodium falciparum and on peritoneal cells of Swiss mice. Pharm Biol. 2017;55:1601–1607. doi: 10.1080/13880209.2017.1313870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campelo Y.D.M., Mafud A.C., Véras L.M.C., et al. Synergistic effects of in vitro combinations of piplartine, epiisopiloturine and praziquantel against Schistosoma mansoni. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;88:488–499. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bezerra D.P., Castro F.O., Alves A.P., et al. In vivo growth-inhibition of Sarcoma 180 by piplartine and piperine, two alkaloid amides from Piper. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2006;39:801–807. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2006000600014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bezerra D.P., Ferreira P.M.P., Machado C.M.L., et al. Antitumour efficacy of Piper tuberculatum and piplartine based on the hollow fiber assay. Planta Med. 2015;81:15–19. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1383363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raj L., Ide T., Gurkar A.U., Foley M., Schenone M., Li X. Selective killing of cancer cells by a small molecule targeting the stress response to ROS. Nature. 2011;475:231–234. doi: 10.1038/nature10167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 23.Cotinguiba F., Regasini L.O., Debonsi H.M., et al. Piperamides and their derivatives as potential anti-trypanosomal agents. Med Chem Res. 2009;18:703–711. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bodiwala H.S., Singh G., Singh R., Dey C.S., Sharma S.S., Bhutani K.K. Antileishmanial amides and lignans from Piper cubeba and Piper retrofractum. J Nat Med. 2007;61:418–421. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silva L.H.P., Nussenzweig V. Sobre uma cepa de Trypanosoma cruzi altamente virulenta para o camundongo branco. Folia clinica et biológica. 1953;20:191–208. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Funayama G.K., Prado J.C. Estudo de caracteres de uma amostra boliviana do Trypanosoma cruzi. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 1974;8:75–81. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fernandes J.F., Castellani O. Growth characteristics and chemical composition of Trypanosoma cruzi. Exp Parasitol. 1966;18:195–202. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alban A., David S.O., Bjorkesten L., et al. A novel experimental design for comparative two-dimensional gel analysis: two-dimensional difference gel electrophoresis incorporating a pooled internal standard. Proteomics. 2003;3:36–44. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200390006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marouga R., David S., Hawkins E. The development of the DIGE system: 2D fluorescence difference gel analysis technology. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2005;382:669–678. doi: 10.1007/s00216-005-3126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tonge R., Shaw J., Middleton B., et al. Validation and development of fluorescence two-dimensional differential gel electrophoresis proteomics technology. Proteomics. 2001;1:377–396. doi: 10.1002/1615-9861(200103)1:3<377::AID-PROT377>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Westermeier R., Scheibe B. Difference gel electrophoresis based on lys/cys tagging. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;424:73–85. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-064-9_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Minden J. Comparative proteomics and difference gel electrophoresis. Biotechniques. 2007;43:739–741. doi: 10.2144/000112653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parodi-Talice A., Durán R., Arrambide N., et al. Proteome analysis of the causative agent of Chagas’ disease: Trypanosoma cruzi. Int J Parasitol. 2004;34:881–886. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andrade H.M., Murta S.M.F., Chapeaurouge A., Perales J., Nirdé P., Romanha A.J. Proteomic analysis of Trypanosoma cruzi resistance to benznidazole. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:2357–2367. doi: 10.1021/pr700659m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Atwood J.A., Weatherly D.B., Minning T.A., Bundy B., Cavola C., Opperdoes F.R. The Trypanosoma cruzi proteome. Science. 2005;309:473–476. doi: 10.1126/science.1110289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Menna-Barreto R.F.S., Beghini D.G., Ferreira A.T.S., Pinto A.V., De Castro S.L., Perales J. A proteomic analysis of the mechanism of action of naphthoimidazoles in Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes in vitro. J Proteomics. 2010;73:2306–2315. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bertino J.R., Waud W.R., Parker W.B., Lubin M. Targeting tumors that lack methylthioadenosine phosphorylase (MTAP) activity. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011;11:627–632. doi: 10.4161/cbt.11.7.14948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Piñeyro M.D., Parodi-Talice A., Portela M., Arias D.G., Guerrero S.A., Robello C. Molecular characterization and interactome analysis of Trypanosoma cruzi Tryparedoxin 1. J Proteomics. 2011;74:1683–1692. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh S., Banerjee R. PLP-dependent H2S biogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1814:1518–1527. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arias D.G., Piñeyro M.D., Iglesias A.A., Guerrero S.A., Robello C. Molecular characterization and interactome analysis of Trypanosoma cruzi tryparedoxin II. J Proteomics. 2015;120:95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alves R.T., Regasini L.O., Funari C.S., et al. Trypanocidal activity of Brazilian plants against epimastigote forms from Y and Bolivia strains of Trypanosoma cruzi. Rev bras Farmacogn. 2010;22:528–533. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kohatsu A.A.N., Silva F.A.J., Francisco A.I., et al. Differential expression on mitochondrial tryparedoxin peroxidase (mTcTXNPx) in Trypanosoma cruzi after ferrocenyl diamine hydrochlorides treatments. Braz J Infect Dis. 2017;21:125–132. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2016.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barbosa C.F., Okuda E.S., Chung M.C., Ferreira E.I., Cicarelli R.M.B. Rapid test for the evaluation of the activity of the prodrug hydroxymethylnitrofurazone in the processing of Trypanosoma cruzi messenger RNAs. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2007;40:33–39. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2007000100005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Santos C.D., Loria R.M., Oliveira L.G., et al. Effects of dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate (DHEA-S) and benznidazole treatments during acute infection of two different Trypanosoma cruzi strains. Immunobiology. 2010;215:980–986. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Finzi J.K., Chiavegatto C.W., Corat K.F., et al. Trypanosoma cruzi response to the oxidative stress generated by hydrogen peroxide. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2004;133:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Piacenza L., Peluffo G., Alvarez M.N., Martínez A., Radi R. Trypanosoma cruzi antioxidant enzymes as virulence factors in Chagas disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;19:723–734. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Friguet B. Oxidized protein degradation and repair in ageing and oxidative stress. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:2910–2916. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moskovitz J. Methionine sulfoxide reductases: ubiquitous enzymes involved in antioxidant defense, protein regulation, and prevention of aging-associated diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1703:213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boschi-Muller S., Gand A., Branlant G. The methionine sulfoxide reductases: catalysis and substrate specificities. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;474:266–273. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moskovitz J., Flescher E., Berlett B.S., Azare J., Poston J.M., Stadtman E.R. Overexpression of peptide-methionine sulfoxide reductase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and human T cells provides them with high resistance to oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:14071–14075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bechtold U., Murphy D.J., Mullineaux P.M. Arabidopsis peptide methionine sulfoxide reductase prevents cellular oxidative damage in long nights. Plant Cell. 2004;16:908–919. doi: 10.1105/tpc.015818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arias D.G., Cabeza M.S., Erben E.D., et al. Functional characterization of methionine sulfoxide reductase A from Trypanosoma spp. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50:37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.10.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]