Abstract

Background

Early antibiotic switch and early discharge protocols have not been widely studied in Latin America. Our objective was to describe real-world treatment patterns, resource use, and estimate opportunities for early switch from intravenous to oral antibiotics and early discharge for patients hospitalized with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus complicated skin and soft-tissue infections.

Materials/methods

This retrospective medical chart review recruited 72 physicians from Brazil to collect data from patients hospitalized with documented methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus complicated skin and soft tissue infections between May 2013 and May 2015, and discharged alive by June 2015. Data collected included clinical characteristics and outcomes, hospital length of stay, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus-targeted intravenous and oral antibiotic use, and early switch and early discharge eligibility using literature-based and expert-validated criteria.

Results

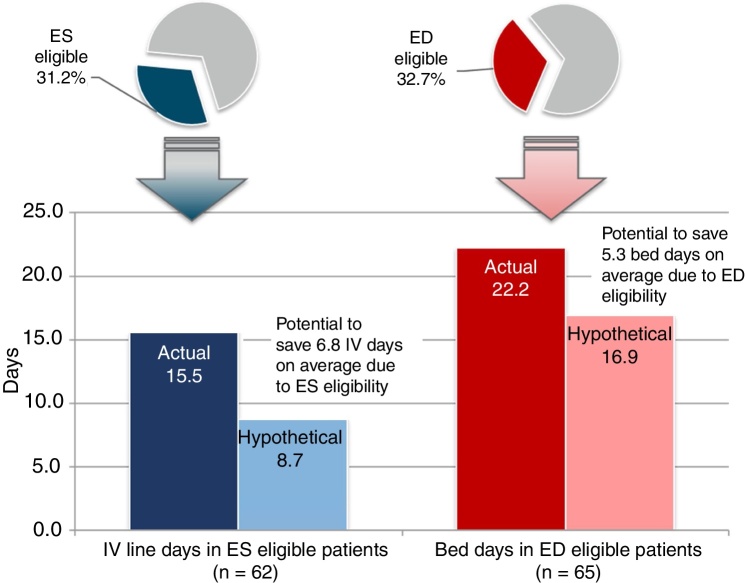

A total of 199 patient charts were reviewed, of which 196 (98.5%) were prescribed methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus -active therapy. Only four patients were switched from intravenous to oral antibiotics while hospitalized. The mean length of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus-active treatment was 14.7 (standard deviation, 10.1) days, with 14.6 (standard deviation, 10.1) total days of intravenous therapy. The mean length of hospital stay was 22.2 (standard deviation, 23.0) days. The most frequent initial methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus-active therapies were intravenous vancomycin (58.2%), intravenous clindamycin (19.9%), and intravenous daptomycin (6.6%). Thirty-one patients (15.6%) were discharged with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus -active antibiotics of which 80.6% received oral antibiotics. Sixty-two patients (31.2%) met early switch criteria and potentially could have discontinued intravenous therapy 6.8 (standard deviation, 7.8) days sooner, and 65 patients (32.7%) met early discharge criteria and potentially could have been discharged 5.3 (standard deviation, 7.0) days sooner.

Conclusions

Only 2% of patients were switched from intravenous to oral antibiotics in our study while almost one-third were early switch eligible. Additionally, one-third of hospitalized patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus complicated skin and soft tissue infections were early discharge eligible indicating opportunity for reducing intravenous therapy and days of hospital stay. These results provide insight into possible benefits of implementation of early switch/early discharge protocols in Brazil.

Keywords: IV-to-PO switch, Length of stay, Clinical criteria, Antibiotic therapy, Economics

Introduction

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) complicated skin and soft tissue infections (cSSTIs), which include all skin and soft tissue infections beyond the superficial and uncomplicated ranging from cellulitis to necrosis, pose an enormous clinical and economic burden within the Brazilian healthcare system.1, 2, 3 The prevalence of MRSA infection is increasing in Latin America reaching 40–50% in most of Latin American countries.4, 5 In Brazil, 45–64% of S. aureus cultures have been reported to be methicillin-resistant.4, 5 MRSA is highly endemic in Brazilian hospitals with 6.1% of adult patients and 2.3% of pediatric patients admitted to a tertiary care hospital screening positive for MRSA.6

Intravenous (IV) antibiotic therapy is the most frequently used treatment among patients hospitalized with cSSTIs, though outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapies (OPAT) and oral (PO) antibiotic therapies exist. Clindamycin, linezolid, doxycycline, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX), and rifampicin alone or in combination with another agent, may be used to treat MRSA cSSTIs; though careful selection is necessary in patients with consideration toward local MRSA resistance.7, 8 Treatment with outpatient and oral antibiotics allow for earlier discharge, reduce direct and indirect medical costs, and have similar cure rates to those of IV antibiotics.9 Once cSSTIs are stabilized, morbidity and mortality remain low regardless of antibiotic formulation allowing for a switch from in-hospital IV treatment to OPAT or PO therapies.

Though there has been an increase in MRSA surveillance and data collection in Brazil and Latin America, real-world data specific to MRSA treatment in Latin America is still limited. A previously published real-world chart review of MRSA cSSTI carried out in 12 European countries evaluated treatment patterns, clinical outcomes, and economic outcomes of patients switched from IV to PO therapy or discharged on OPAT.10, 11 Our study sought to apply this approach to evaluate early switch (ES) and early discharge (ED) opportunities in MRSA cSSTI patients in Brazil.

Methods

This retrospective observational medical chart review recruited 72 physicians (34 infectious disease specialists, 38 internal medicine specialists) from 79 hospitals and health clinics in Brazil, who collected data on 199 patients. This study was an extension of a chart review in 12 European countries that has been published elsewhere.10, 11 Data were collected from medical records of patients treated for a documented MRSA cSSTI, and admitted to the hospital between 01 May 2013 and 30 May 2015, and discharged alive by 30 June 2015. Patients were randomly sampled for data on real-world treatment patterns, clinical outcomes, and resource utilization. Those who could have been switched from IV to PO MRSA therapy and those who could have been discharged earlier (via use of oral antibiotics or OPAT) based on the eligibility criteria in Table 1 were identified, and the potential reductions in IV-line usage for antibiotic administration and hospital length of stay (LOS) were calculated.

Table 1.

IV and Length of Stay Related Endpoints

| IV-related endpoints | • Actual length of IV usage: time between initiation of MRSA-active IV therapy and last day of MRSA-active IV therapy (for patients switched from IV to PO) or discharge (IV only patients) |

| • ES eligibility: At minimum, the following key criteria needed to be met prior to actual IV discontinuation: | |

| □ Stable clinical infection | |

| □ Afebrile/temperature <38 °C for 24 h | |

| □ WBC count normalizing, WBC not <4 × 109/L or >12 × 109/L | |

| □ No unexplained tachycardia | |

| □ Systolic blood pressure ≥100 mmHg | |

| □ Patient tolerates PO fluids/diet and able to take PO medications with no gastrointestinal absorption problems | |

| • Hypothetical IV days: Days between the day of initial MRSA-active IV antibiotic administration and date when patient satisfied the last of the key ES criteria listed above | |

| • Potential reduction in IV days: Difference in days between actual and hypothetical IV days among ES eligible patients | |

| LOS-related endpoints | • LOS (from beginning of cSSTI episode): Number of days from cSSTI indexa to hospital discharge |

| • ED eligibility: At minimum, the following criteria needed to be met prior to discharge | |

| □ All key ES eligibility criteria listed above | |

| □ No other reason to stay in hospital except infection management | |

| • Hypothetical LOS: Number of days from cSSTI indexa to the date that patient satisfied all key required criteria and actual LOS | |

| • Potential reduction in LOS (bed days saved): Difference in days between actual and hypothetical LOS among ED eligible patients |

Abbreviations: cSSTI, complicated skin and soft tissue infection; ED, early discharge; ES, early switch; IV, intravenous; LOS, length of stay; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; OPAT, outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy; PO, oral; WBC, white blood cell.

Date of admission for patients admitted for cSSTI; cSSTI diagnosis date otherwise. In cases where the cSSTI diagnosis date was before admission, the date of admission was used.

Patient selection

Study investigators (hospital-based infectious disease specialists, internal medicine specialists with an infectious disease sub-specialty, or medical microbiologists) identified subjects eligible for inclusion. To be included, patients must have had a microbiologically confirmed MRSA cSSTI (e.g., deep or extensive cellulitis, infected wound or ulcer, major abscess or other soft tissue infection requiring substantial surgical intervention), and received ≥3 days of IV anti-MRSA antibiotics including, but not limited to: clindamycin, daptomycin, fusidic acid, linezolid, rifampicin, teicoplanin, tigecycline, TMP/SMX, or vancomycin, during their hospital stay. Patients were excluded if they had been treated for the same cSSTI within three months of hospitalization, or had suspected or proven diabetic foot infections, osteomyelitis, infective endocarditis, meningitis, joint infections, necrotizing soft tissue infections, gangrene, prosthetic joint infection, or prosthetic implant/device. Additionally, patients were excluded if they were less than 18 years old, pregnant or lactating, had significant concomitant infection at other sites, were immunosuppressed (e.g., diagnosed hematologic malignancy, neutropenia, or rheumatoid arthritis; receiving chronic steroids or cancer chemotherapy), or enrolled in another cSSTI-related clinical trial.

Key outcomes

The key study outcomes were patient treatment patterns, clinical outcomes, and opportunities for early switch or early discharge.

Treatment patterns analyzed included time to MRSA-active treatment from cSSTI index date and number of MRSA-active treatment received. Patients’ first, last, and discharge (if applicable) MRSA-active treatment were recorded. Additionally, length of total antibiotic therapy, (time between initiation of MRSA-active therapy and last day of MRSA-active therapy or discharge); length of IV antibiotic therapy (subset of MRSA-active therapy days for which IV antibiotics were prescribed) were assessed. Length of stay (number of days from hospital admission for patients admitted for cSSTI, or cSSTI diagnosis date to hospital discharge) was also calculated for all patients.

Clinical outcomes included clinical response at end of each MRSA-active therapy, end of full MRSA-active treatment, and at hospital discharge. Development of IV-line infections, super infections, and severe sepsis were documented. Patients were also followed to record cSSTI relapse due to MRSA within 30 days of discharge or unplanned re-hospitalization for cSSTI or other health issues.

Literature review and expert consensus were used to create ES and ED eligibility criteria applicable to real-world clinical settings.12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 For ES eligibility, at a minimum, patients had to meet all of the following key criteria prior to IV antibiotic discontinuation: stable clinical infection, afebrile/temperature <38 °C for 24 h, normalized white blood cell (WBC) count (4 × 109/L < WBC < 12 × 109/L), no unexplained tachycardia, systolic blood pressure ≥100 mmHg able to tolerate PO fluids/diet and take PO medication with no gastrointestinal absorption problems. For ED eligibility, at a minimum, patients had to meet the above key criteria for ES prior to discharge and have no other reason to remain in the hospital except for infection management.

To estimate resource use savings, potential reduction in IV days was calculated for ES patients and bed days saved were calculated for ED patients, using hypothetical and actual treatment patterns. Hypothetical length of IV therapy was calculated as the length of time between date of initial MRSA-active IV therapy and date when patient satisfied key ES criteria. Potential reduction in IV days was the difference in days between actual length of MRSA targeted therapy from hypothetical length of MRSA targeted therapy. Hypothetical LOS was calculated as number of days from cSSTI index date to date that patients satisfied all key criteria. Bed days saved was the difference in days between actual and hypothetical length of stay for ED eligible patients. The economic impact of mean cost per bed days saved in ED eligible patients was calculated by multiplying the bed days saved by a Brazil-specific unit cost of $31 international dollars (Intl.) (45 Brazilian real [BRL]) per bed day based on World Health Organization (WHO)-reported unit costs for providing a Brazil hospital bed day in the year 2007; this was reported in international dollars (local currency units) and adjusted for inflation (percent change in consumer price index) to the year 2015.19, 20 Costs included by the WHO represent the “hotel” component of hospital costs, such as personnel, capital, and food, and do not include drug and diagnostic test costs.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted for all outcomes; frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, and means, medians, and interquartile ranges for continuous variables. Results were analyzed using SAS software version 9.4.

Results

Patient and hospital characteristics

Data was collected from medical charts of 199 patients in Brazil with MRSA cSSTIs. Almost half of patients were Caucasian (45%), followed by equal proportions of black/African and Latino patients (19%, respectively). Most patients were male (64%), and the average age at hospital admission was 52 years (Table 2). More than three-quarters of patients (78%) reported comorbidities, with diabetes (49%), coronary artery disease (28%) and peripheral vascular disease (19%) being most frequently reported. About 80% of patients reported treatment of MRSA cSSTI as the primary reason for hospitalization, with 29% of patients presenting with deep or extensive cellulitis, 28% with a surgical site infection, and 18% with an infected ulcer. Over half (59%) of all cSSTIs were community acquired, and a smaller proportion were hospital acquired (18%) or healthcare-associated (16%) infections. Only 6% of patients had been infected with MRSA a year prior to hospitalization.

Table 2.

Patient and Disease Characteristics

| Variable | Brazil (n = 199) |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 52.0 (5.7) |

| Male, n (%) | 128 (64.3) |

| Caucasian, n (%) | 92 (46.2) |

| At least one comorbidity, N (%) | 155 (77.9) |

| Diabetes | 76 (49.0) |

| Coronary artery disease (incl. myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass graft, etc.) | 43 (27.7) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 29 (18.7) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 23 (14.8) |

| Congestive heart failure | 21 (13.5) |

| Other Comorbidity | 17 (11.0) |

| Diabetes with end organ damage | 15 (9.7) |

| Mild liver disease | 12 (7.7) |

| Primary reason for hospitalization is treatment of MRSA cSSTI, n (%) | 153 (80.1) |

| Type of cSSTI, n (%) | |

| Deep/extensive cellulitis | 57 (28.6) |

| Infected burn | 9 (4.5) |

| Infected ulcer | 35 (17.6) |

| Major abscess | 26 (13.1) |

| Posttraumatic wound infection | 17 (8.5) |

| Surgical site infection | 55 (27.6) |

| Source of cSSTI, n (%) | |

| Community acquired | 117 (58.8) |

| Healthcare-associated (prior hospitalization in the past 90 days, residence in a nursing home or extended care facility | 32 (16.1) |

| Hospital acquired (>48 h after admission) | 35 (17.6) |

| Unknown/not documented | 15 (7.5) |

| MRSA infection within 12 months prior to hospitalization, n (%) | 11 (5.5%) |

| Surgical procedure related to cSSTI treatment, n (%) | 52 (26.1) |

| Incision/drainage | 28 (53.8) |

| Debridement | 21 (40.4) |

| Othera | 2 (3.8) |

| Revascularization | 2 (3.8) |

| Closure of wound | 1 (1.9) |

| Removal of prosthesis | 1 (1.9) |

| Infections during hospitalization, n (%) | |

| IV-line infection | 5 (2.5) |

| Super infection | 10 (5.0) |

| Severe sepsis or septic shock | 51 (25.6) |

Abbreviations: cSSTI, complicated skin and soft tissue infection; h, hour; incl, include; IV, intravenous; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; SD, standard deviation.

Other = skin grafting, resection.

All but one of the 79 hospital sites had an antibiotic subcommittee or steering committee. Fewer hospitals had an IV to PO antibiotic switch protocol (20%) or discharge protocol (11%) for patients admitted for cSSTI MRSA. However, one-fourth of hospitals reported having OPAT available.

Actual treatment patterns and healthcare resource utilization

All but three patients (99%) received at least one MRSA-active therapy. Of patients treated with MRSA-active therapy, 161 patients (82%) did not require subsequent antibiotic therapy, 33 patients (17%) required two courses, and two patients (1%) required three courses (Table 3). The mean time of administration of MRSA-active therapy was 2.1 days (SD 6.3) following MRSA cSSTI diagnosis. Only four patients (2%) were switched from IV-to-PO MRSA-active therapy while hospitalized. Average LOS from cSSTI diagnosis through discharge was 20.7 (SD 18.6) days. About one-quarter of cSSTIs (26%) warranted surgical procedures, incision and drainage of the infection (54%) and debridement (40%) were performed most frequently. Severe sepsis or septic shock occurred among approximately one-quarter (26%) of those hospitalized, while super infection (5%) and IV-line infection (3%) were rarely found.

Table 3.

Actual Antibiotic Use in Patients Treated with MRSA-Active Antibiotics

| Variable | Brazil (n = 196) |

|---|---|

| Patient switched from IV to oral inpatient MRSA-active antibiotic treatment, n (%) | 4 (2.0) |

| Days to MRSA targeted therapy, from cSSTI index date, n (%) | |

| On or before cSSTI index | 124 (63.3) |

| 1–2 days post cSSTI index | 29 (14.8) |

| 3+ days post cSSTI index | 43 (21.9) |

| Number of MRSA targeted courses of therapy, n (%) | |

| 1 | 161 (82.1) |

| 2 | 33 (16.8) |

| 3 | 2 (1.0) |

| MRSA active days of therapy (including PO), mean (SD) | 14.7 (10.1) |

| MRSA active IV days, mean (SD) | 14.6 (10.1) |

| MRSA targeted antibiotics used in initial line, n (%) | |

| Vancomycin IV | 114 (58.2) |

| Clindamycin IV | 39 (19.9) |

| Daptomycin IV | 13 (6.6) |

| TMP-SMX IV | 7 (3.6) |

| Linezolid IV | 6 (3.1) |

| Othera | 17 (8.6) |

| MRSA targeted antibiotics used in last line, n (%) | |

| Vancomycin IV | 104 (53.1) |

| Clindamycin IV | 28 (14.3) |

| Daptomycin IV | 22 (11.2) |

| Linezolid IV | 18 (9.2) |

| TMP-SMX IV | 6 (3.1) |

| Otherb | 18 (9.1) |

| Patient received targeted antibiotic at discharge, n (%) | 31 (15.8) |

| Oral targeted therapy | 25 (80.6) |

| MRSA-active antibiotics prescribed at discharge, n (%) | 31 (15.8) |

| Clindamycin PO | 13 (41.9) |

| Linezolid PO | 5 (16.1) |

| TMP-SMX PO | 3 (9.7) |

| Daptomycin IV | 3 (9.7) |

| Vancomycin IV | 2 (6.5) |

| Ciprofloxacin PO | 2 (6.5) |

Abbreviations: cSSTI, complicated skin and soft tissue infection; IV, intravenous; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; PO, oral; SD, standard deviation; TMP-SMX, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

Other includes: cefuroxime IV, ciprofloxacin IV + clindamycin IV, clindamycin IV, clindamycin IV + linezolid IV, clindamycin IV + TMP-SMX IV, clindamycin PO, daptomycin IV, doxycycline PO, linezolid IV, oxacillin IV, TMP-SMX IV, teicoplanin IV, teicoplanin IV + tigecycline IV, tigecycline IV, trimethoprim IV.

Other includes: ciprofloxacin IV, linezolid PO, oxacillin IV, piperacillin/tazobactam IV, TMP-SMX PO, teicoplanin IM, teicoplanin IV, tigecycline IV.

The most frequently prescribed antibiotics did not change between initial line and final line treatment, with vancomycin IV (initial 58%, final 53%), clindamycin IV (initial 20%, final 14%), and daptomycin IV (initial 7%, final 9%) used most frequently. However, analysis of final inpatient MRSA-active antibiotic regimens showed that throughout the course of treatment, the proportion of inpatients receiving vancomycin IV or clindamycin IV decreased, while the proportion of patients receiving daptomycin IV or linezolid IV increased. At discharge, 31 patients (16%) were prescribed a MRSA-active antibiotic, and four-fifths of these were oral targeted therapy. Clindamycin PO (42%), linezolid PO (16%), and TMP-SMX PO (10%) were the most commonly prescribed oral antibiotics at discharge while daptomycin IV (10%) and vancomycin IV (7%) were the most common IV antibiotics. Antibiotic susceptibilities in this sample are presented in Table 4 and show susceptibility rates < 40% for the commonly used oral agents TMP-SMX and clindamycin. Mean length of MRSA-active antibiotic treatment regardless of route (i.e., IV, intramuscular, or PO) was 14.7 (SD 10.1) days, while MRSA-active IV antibiotic treatment lasted a mean of 14.6 (SD 10.1) days.

Table 4.

MRSA cSSTI Susceptibility Profile

| Antibiotica | All |

|

|---|---|---|

| N tested | % sensitive | |

| Linezolid | 116 | 100 |

| Vancomycin | 135 | 97.0 |

| Tigecycline | 87 | 96.6 |

| Daptomycin | 62 | 91.9 |

| Quinupristin–dalfopristin | 18 | 66.7 |

| Rifampicin | 48 | 64.6 |

| Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) | 119 | 37.0 |

| Clindamycin | 122 | 36.1 |

| Minocycline | 22 | 27.3 |

| Doxycycline | 63 | 20.6 |

| Fusidic Acid | 28 | 17.9 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 121 | 11.6 |

| Trimethoprim | 44 | 6.8 |

| B-lactam antibiotic/penicillin | 102 | 5.9 |

Other antibiotics with <10 tests, N tested (% sensitive): amikacin, 2 (100%); polymyxin, 1 (100%); gentamicin, 6 (66.7%); oxacillin, 2 (50%).

At discharge, over half of patients (55%) showed resolution of signs and symptoms or improvement to such an extent that further therapy was not necessary (Table 5). In total, 69 patients (35%) were discharged with an improvement in their signs and symptoms, and 14 (7%) were discharged after failure to cure or improve cSSTI signs and symptoms. Relapse and re-hospitalization for a cSSTI due to MRSA within 30 days post-discharge occurred in only two (1%) patients while re-hospitalization for any reason occurred in 11 (6%) patients.

Table 5.

MRSA Clinical Outcomes

| Variable | All (n = 196) |

|---|---|

| Clinical response at discharge, n (%) | |

| Curea | 107 (54.6) |

| Improvementb | 69 (35.2) |

| Failure | 14 (7.1) |

| Indeterminatec | 6 (3.1) |

| Outcomes 30 days post-discharge (n = 199) | |

| cSSTI relapse due to MRSA, n (%) | 2 (1.0) |

| Days from discharge to relapse, mean (SD) | 17.0 (12.7) |

| Re-hospitalization for cSSTI due to MRSA, n (%) | 2 (1.0) |

| LOS, mean (SD) | 19.5 (6.4) |

| Re-hospitalization for any reason, n (%) | 11 (5.5) |

Abbreviations: cSSTI, complicated skin and soft-tissue infection; LOS, length of stay; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; SD, standard deviation.

Cure: resolution of All signs and symptoms of cSSTI due to MRSA/improvement to such an extent that further antimicrobial therapy was not necessary.

Improvement: improvement in signs and symptoms of cSSTI due to MRSA.

Indeterminate: inability to determine an outcome.

Actual and hypothetical outcomes based on ES/ED eligibility

A total of 62 (31%) patients met all six key ES criteria prior to actual IV discontinuation. Among the ES-eligible patients, the actual mean length of IV therapy was 15.5 (SD 11.1) days but hypothetically could have been 8.7 (SD 8.9) days when removing days after patients met all ES criteria, suggesting a potential reduction in IV therapy duration of 6.8 (SD 7.8) days (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Brazil Comparison of Actual and Hypothetical IV-line and Bed Days in ES- and ED-eligible Patients.

Abbreviations: ED, early discharge; ES, early switch; IV, intravenous.

Approximately one-third (32.7%) of patients met all key ED criteria prior to hospital discharge. The actual mean LOS for patients meeting key ED criteria was 22.2 (SD 23.0) days; the hypothetical LOS for these patients was 16.9 (SD 21.5) days, suggesting a potential reduction in LOS of 5.3 (SD 7.0) days. Assuming an average cost of $31 Intl, (45 real) per bed day, the total savings would be $164 Intl. (239 real) in bed-day cost savings per ED-eligible patient.

Discussion

No other studies have used patient treatment data to evaluate real-world clinical practice and opportunities for ES and ED in hospitalized patients with MRSA cSSTIs in Brazil. We found that, prior to actual discharge, almost one-third of patients with MRSA cSSTIs met criteria for ES and ED. For those found eligible, LOS could have been reduced by 5.3 days and IV therapy days by 6.8 days. These results offer insight into the potential policy and economic implications of identifying ES and ED eligible patients. Our study provides a snapshot of management patterns in Brazil, specifically clinical outcomes and resource utilization details, making this dataset unique.

Our research demonstrates a great opportunity for ES/ED antibiotic policies in Brazil when compared with Europe and USA where early discharge policies already exist in some institutions. Though 31% of patients on IV antibiotic therapies were eligible for ES and 33% ED, only 2% were switched from IV-to-PO therapies, and potential decreases in LOS totalled 5.3 days and 6.8 IV days. The rates of ES and ED eligibility observed in our study are similar to findings in prior research that showed 30–50% of patients in Europe and United States could be switched from IV to PO antibiotic therapy12, 16, 21, 22, 23, 24 and 20–30% discharged earlier on PO antibiotic therapy.12, 16, 23 Similar rates of ES and ED eligibility, using an identical methodology, have been reported in a 12-country study in Europe. Rates of eligibility ranged from 12.0% (Slovakia) to 56.3% (Greece) for ES, and 10.0% (Slovakia) to 48.2% (Portugal) for ED, which are inclusive of Brazil's eligibility rates of 31% and 33%, respectively.10, 25

Our results show the importance of taking MRSA susceptibility into account when deciding upon patient regimens. Vancomycin IV and, daptomycin IV were frequently prescribed as active treatments against MRSA, both of which show susceptibility above 90% in this sample (Table 4). Clindamycin IV which presented susceptibility rates of 36% only when tested against MRSA samples, was the second most commonly used therapy in the initial and final inpatient active treatment regimens. In addition, clindamycin PO was the most prescribed antibiotic at discharge, representing 42% of discharged patients regimens. In fact, the three PO therapies most frequently prescribed on discharge represented 68% of all regimens suggesting other PO antibiotic therapies should be kept in mind.

Because Brazil does not have a national antimicrobial resistance surveillance system and previous MRSA studies sampled a small number of centers, our study provides additional information to the literature. The high rates of antibiotic resistance seen to TMP-SMX (63%), clindamycin (64%), and doxycycline (80%) in our study may be explained by a unique epidemiologic situation in Brazil. There is a hospital-acquired Brazilian endemic clone (BEC) of MRSA resistant to many antibiotics (<10% of these clones are susceptible to clindamycin, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, ciprofloxacin, gentamicin).26 A more resistant strain of MRSA in Brazil underscores the need for physicians to be more cautious when acting on opportunities for ES and ED. In our study, linezolid retained high activity against MRSA (Table 4) and could be considered an IV or oral option given the resistance to other more frequently used oral antibiotics.

Since this study was a retrospective medical chart review, our results are subject to the well-known limitations of this study design. Because information was limited to medical charts, dates that patients met criteria for ES and ED were estimated based on data available in the patients’ medical records if these dates were not recorded. Also, it was not possible to proactively apply ES and ED criteria to determine the actual (rather than potential) cost-savings using a retrospective study design. Ideally, the applicability of the ES and ED criteria used in this study needs to be validated prospectively. Additionally, 99% of the hospitals in this study were in urban settings (vs. rural), where population demographics, prevalence of MRSA-cSSTI, access to care, and costs may differ. Also, treatment patterns presented in this study represent the practices of included physicians which may vary by physicians and hospitals due to medication access. Finally, only patients diagnosed with MRSA cSSTI between 2013 and 2015 were included in this study but due to increasing MRSA resistance and decreasing drug susceptibility disease management and treatment patterns may have changed.

Conclusions

This is the first full scale study to analyze early switch and early discharge opportunities in Latin America, specifically in Brazil. Our results suggest that one-third of patients with MRSA cSSTI in Brazil could be switched from IV to oral therapy and discharged from the hospital earlier which could result in potential cost saving for the Brazilian healthcare system. Although specific to cSSTIs, these results suggest that hospitals in Latin America could consider adopting early switch and early discharge protocols to their antibiotic stewardship strategies, increasing provider and patient benefits.

Author contributions

Guilherme Furtado, Jaime Rocha, Ricardo Hayden, Caitlyn T. Solem, Wing Yu Tang, Jennifer M. Stephens, Richard Chambers, Seema Haider, and Maria Lavínea Novis de Figueiredo contributed to the study design. Cynthia Macahilig was involved in data acquisition. Caitlyn T. Solem, Jennifer M. Stephens, and Courtney Johnson undertook data analysis. All authors contributed to the interpretation of data, drafting of this manuscript, and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure

This study was sponsored by Pfizer Inc. Guilherme Furtado, Jaime Rocha, and Ricardo Hayden were paid consultants to Pfizer. Jennifer M. Stephens, Caitlyn T. Solem, and Courtney Johnson are employees of Pharmerit International and were paid consultants to Pfizer in connection with this study. Cynthia Macahilig is an employee of Medical Data Analytics, a subcontractor to Pharmerit International for this project. Wing Yu Tang, Richard Chambers, Seema Haider, and Maria Lavínea Novis de Figueiredo are employees of Pfizer.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. This study was sponsored by Pfizer.

Acknowledgments

Clinical experts involved in the original study design, which was adapted to Brazil: United Kingdom: Dilip Nathwani, Wendy Lawson; Germany: Christian Eckmann; France: Eric Senneville; Spain: Emilio Bouza; Italy: Giuseppe Ippolito; Austria: Agnes Wechsler Fördös; Portugal: Germano do Carmo; Greece: George Daikos; Slovakia: Pavol Jarcuska; Czech Republic: Michael Lips, Martina Pelichovska; and Ireland: Colm Bergin.

References

- 1.Edelsberg J., Berger A., Weber D., Mallick R., Kuznik A., Oster G. Clinical and economic consequences of failure of initial antibiotic therapy for hospitalized patients with complicated skin and skin-structure infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29:160–169. doi: 10.1086/526444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hatoum H., Akhras K., Lin S. The attributable clinical and economic burden of skin and skin structure infections in hospitalized patients: a matched cohort study. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;64:305–310. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lipsky B., Weigelt J., Gupta V., Killian A., Peng M. Skin, soft tissue, bone, and joint infections in hospitalized patients: epidemiology and microbiological, clinical, and economic outcomes. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28:1290–1298. doi: 10.1086/520743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garza-González E., Dowzicky M. Changes in Staphylococcus aureus susceptibility across Latin America between 2004 and 2010. Braz J Infect Dis. 2013;17:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2012.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guzmán-Blanco M., Mejía C., Isturiz R., et al. Epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in Latin America. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009;34:304–308. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santos H.B., Machado D.P., Camey S.A., Kuchenbecker R.S., Barth A.L., Wagner M.B. Prevalence and acquisition of MRSA amongst patients admitted to a tertiary-care hospital in brazil. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:328. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dellit T.H., Owens R.C., John E., McGowan J., et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America Guidelines for Developing an Institutional Program to Enhance Antimicrobial Stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:159–177. doi: 10.1086/510393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cunha B.A. Oral antibiotic therapy of serious systemic infections. Med Clin North Am. 2006;90:1197–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nathwani D., Lawson W., Dryden M., et al. Implementing criteria-based early switch/early discharge programmes: a European perspective. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21(Suppl. 2):S47–S55. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eckmann C., Lawson W., Nathwani D., et al. Antibiotic treatment patterns across Europe in patients with complicated skin and soft-tissue infections due to meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a plea for implementation of early switch and early discharge criteria. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2014;44:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nathwani D., Eckmann C., Lawson W., et al. Pan-European early switch/early discharge opportunities exist for hospitalized patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus complicated skin and soft tissue infections. Clin Microbiol Infect Off Publ Eur Soc Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014 doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Desai M., Franklin B.D., Holmes A.H., et al. A new approach to treatment of resistant gram-positive infections: potential impact of targeted IV to oral switch on length of stay. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6:94. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matthews P.C., Conlon C.P., Berendt A.R., et al. Outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT): is it safe for selected patients to self-administer at home?. A retrospective analysis of a large cohort over 13 years. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60:356–362. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seaton R.A., Bell E., Gourlay Y., Semple L. Nurse-led management of uncomplicated cellulitis in the community: evaluation of a protocol incorporating intravenous ceftriaxone. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;55:764–767. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tice A.D., Rehm S.J., Dalovisio J.R., et al. Practice guidelines for outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy. IDSA guidelines. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:1651–1672. doi: 10.1086/420939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parodi S., Rhew D.C., Goetz M.B. Early switch and early discharge opportunities in intravenous vancomycin treatment of suspected methicillin-resistant staphylococcal species infections. J Manag Care Pharm. 2003;9:317–326. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2003.9.4.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nathwani D., Moitra S., Dunbar J., Crosby G., Peterkin G., Davey P. Skin and soft tissue infections: development of a collaborative management plan between community and hospital care. Int J Clin Pract. 1998;52:456–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee S.L., Azmi S., Wong P.S. Clinicians’ knowledge, beliefs and acceptance of intravenous-to-oral antibiotic switching, Hospital Pulau Pinang. Med J Malaysia. 2012;67:190–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The World Bank . 2016. Consumer Price Index (2010 = 100) https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/FP.CPI.TOTL?page=6 [accessed 11.08.17] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization . 2011. WHO-CHOICE unit cost estimates for service delivery. http://www.who.int/choice/country/country_specific/en/index.html [accessed 11.08.17] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buyle F.M., Metz-Gercek S., Mechtler R., et al. Prospective multicentre feasibility study of a quality of care indicator for intravenous to oral switch therapy with highly bioavailable antibiotics. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:2043–2046. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Di Giammarino L., Bihl F., Bissig M., Bernasconi B., Cerny A., Bernasconi E. Evaluation of prescription practices of antibiotics in a medium-sized Swiss hospital. Swiss Med Week. 2005;135:710–714. doi: 10.4414/smw.2005.11174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dryden M., Saeed K., Townsend R., et al. Antibiotic stewardship and early discharge from hospital: impact of a structured approach to antimicrobial management. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:2289–2296. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mertz D., Koller M., Haller P., et al. Outcomes of early switching from intravenous to oral antibiotics on medical wards. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;64:188–199. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nathwani D., Eckmann C., Lawson W., et al. Pan-European early switch/early discharge opportunities exist for hospitalized patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus complicated skin and soft tissue infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:993–1000. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rossi F. The challenges of antimicrobial resistance in Brazil. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:1138–1143. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]