Abstract

Background and Objects: Malignant phyllodes tumor of the breast (MPTB) is a rare tumor for which surgery or surgery combined with radiotherapy (RT) is the primary treatment method. However, recently, the therapeutic effect of RT on MPTB has been controversial. We aimed to explore the role of RT, chemotherapy (CT), and surgical modalities in patients with MPTB. Methods: The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database was used to select patients with MPTB who met the criteria between 2010 and 2018. Kaplan–Meier curves and Cox proportional risk regression models were used to analyze the effects of RT on MPTB patients. Based on this, we compared the effects of breast-conserving surgery (BSC) and mastectomy on the postoperative survival of MPTB. Results: A total of 298 patients with MPTB were included in this study. RT was received by 22.1% (n = 66) of the patients while 77.9% (n = 232) did not receive RT. CT was received by 4.7% (n = 14) patients while 95.3% (n = 284) did not receive CT. According to Kaplan–Meier curves, RT and CT combined resulted in a decrease in breast cancer-specific survival (BCSS) and overall survival (OS) compared to patients who did not receive RT. Mastectomy improved the OS and BCSS of the patients more than BCS). The findings of univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses suggested that “distant metastasis”, “tumor grade” and “number of positive lymph node biopsies” affected OS of breast cancer, while “distant metastasis”, “tumor grade”, “surgery combined with radiotherapy/surgery”, and “radiotherapy/chemotherapy or not”, had a significant effect on BCSS. Conclusion: RT and CT did not significantly improve the long-term survival of MPTB patients. Mastectomy improved OS and BCSS of the patient more than BCS. RT in an early stage improved early prognosis moderately in MPTB patients with tumor diameter less than 50 mm.

Keywords: MPTB, SEER, phyllodes tumor, breast, survival, breast cancer

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common malignant tumor. Malignant phyllodes tumor of the breast (MPTB) is extremely rare compared to other types of breast cancer, accounting for approximately 0.5% of all breast malignancies. MPTB is characterized by bidirectional differentiation with very few lymph node metastases, mainly hematogenous. The most common site is the lung, so axillary lymph node dissection is not recommended. Moreover, MPTB has limited sensitivity to chemotherapy (CT) due to its specificity in terms of pathology and treatment. All of the above factors distinguish MPTB from other types of breast cancer, deeming it worthy of special treatment and research. Breast cancer incidence, morbidity, and mortality rates in China have increased in recent years due to economic development. Westernized lifestyle and fertility patterns may be one of the reasons for the increasing incidence of breast cancer in China year by year. 1 The main reasons for the higher breast cancer mortality rate in China than in Europe may be a lack of early diagnosis and inappropriate radiotherapy (RT). The phyllodes tumor of the breast (PTB) is a rare tumor that accounts for about 2% to 3% of all fibroepithelial tumors of the breast and 0.3% to 1.0% of all breast tumors. In 2003, the International Histological Classification Panel of the World Health Organization (WHO) named it PTB and classified it into benign, borderline, and malignant subtypes. The diagnostic accuracy of benign and borderline PTB is generally lower than MPTB, and the high local recurrence rate is the most important prognostic feature of MPTB. Inappropriate surgical approaches, RT and CT, can result in a proclivity for rapid growth and metastasis.2,3 MPTB accounts for 20% of all PTB, and clinical features such as aggressiveness, local recurrence, and distant metastasis are prominent. MPTB is most common in women of childbearing age, particularly in patients with a history of benign breast disease, such as fibroadenomas. 4 MPTB has an insidious onset with a rapid progression. The lesions often present as unilateral, solitary, nodular, and painless masses ranging from 1 cm to 40 cm in size. 5

Surgery is the preferred treatment of choice for PTB. Lymph node dissection is generally not recommended because lymph node metastases are rare in MPTB. In case of a local recurrence of the mass following the surgery, a second surgery can be performed in the absence of metastasis, and adjuvant RT and CT may be considered depending on the condition. However, the efficacy of RT and CT is unclear, and the effectiveness in controlling the recurrence of different histological types of PTB is not definitive; therefore, it has been the focus of many investigators. Regrettably, progress has remained minimal over the years, and many researchers have found contradictory results on this topic.6–13 Some investigators have concluded that postoperative RT significantly reduces the likelihood of recurrence in the clinical management of patients with MPTB. However, many studies only analyzed the prognosis of PTB but did not classify and study breast cancer-specific survival (BCSS) or overall survival (OS) in MPTB patients. Therefore, this study fills the gap in previous studies by selecting specific MPTB patients from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database to analyze them from the perspectives of surveillance, epidemiology, and outcome. This study investigated whether MPTB patients could benefit from adjuvant RT and CT and further compared the effects of breast-conserving surgery (BCS) and mastectomy on the postoperative survival of MPTB patients.

Materials and Methods

Patients

The SEER database is an open resource for cancer-based demographics, clinical information, treatment, and patient survival status in the United States of America (USA). We used SEER*Stat version 8.3.5 (http://www.seer.cancer.gov/seerstat) to identify and obtain patients with MPTB from the database from 2010 to 2018 who met the relevant criteria. The inclusion criteria for MPTB patients were female, year of diagnosis was 2010 to 2018, the main clinical presentation was diagnosis of a breast mass, pathologically confirmed MPTB (ICD-O-39020/3) whether treated with mastectomy, BCS, RT, or with CT. Demographic variables included age at diagnosis (≤ 35, 35-55, ≥ 55), survival time, survival status, cause of death (death from breast cancer or other cause of death), and race (White, Black, or another race). Tumor characteristics were: tumor located on the left or right side, T stage (T0, T1, T2, T3, and T4), N stage (N0, N1, N2, and N3), surgery combined with RT/surgery alone, tumor size, tumor grade (G1, G2, G3, and G4), number of local lymph node biopsies, and number of positive lymph node biopsies. The data can be obtained from the corresponding author.

Statistical Analysis

The chi-square test was used to compare baseline characteristics, including demographic characteristics, tumor characteristics, and clinical characteristics, between patients who received adjuvant RT and those who did not. OS was the primary outcome, defined as the time from tumor diagnosis to death from any cause. BCSS was also included for comparison, defined as the time from tumor diagnosis to death due to MPTB. Kaplan–Meier survival curves and multivariate Cox proportional risk models were utilized to identify prognostic factors associated with BCSS, OS, and hazard ratios (HRs) and reported 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). All analyses were performed using SPSS (version 24.0; SPSS, Inc.). Statistical significance was assumed at P values < .05.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

A total of 298 patients with MPTB were included in this study, of which 66 (22.1%) received adjuvant RT, and 232 (77.9%) did not, 14 (4.5%) received CT, and the remaining 284 (90.7%) received no CT. Approximately 66 (22.1%) underwent surgery in conjunction with RT, while the remaining 232 (77.9%) were treated surgically only. One hundred and fifty (50.3%) patients aged 35 to 55. The mean survival time was 42.62 ± 23.22 days. Two hundred and fifty-four (85.2%) patients survived, 32 (10.7%) died due to MPTB, and 12 (4.0%) died due to other causes. Two hundred and twenty-six (75.8%) were Caucasian, 26 (8.7%) were Afro-American, and 46 (15.4%) were of other races. One hundred and sixty-six (55.7%) patients had tumors < 50 mm and 132 (44.3%) patients had tumors ≥ 50 mm. For clinical staging, G1 (93 cases, 31.2%), G2 (61 cases, 20.5%), G3 (87 cases, 29.2%), and G4 (57 cases, 19.1%). One hundred and fifty-five (52.0%) had left-sided masses and 143 (48.0%) had right-sided masses. Axillary lymph node biopsy was performed in patients, of which 3 (1.1)% had positive biopsies. For surgical modality, 4 (1.3%) did not opt for surgery, 127 (42.6%) opted for a mastectomy, and 167 (56.0%) underwent BCS. For the RT and non-RT groups, there were statistically significant differences in tumor size (P = .014) and tumor grade (P = .000). The demographic characteristics, tumor characteristics, and treatment information of MPTB patients are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of Baseline Characteristics in the Radiotherapy (RT) and non-RT Groups.

| Variable | Total patients | RT group | Non-RT group | Z value | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | n = 66 (22.1%) | n = 232 (77.9%) | |||

| Age (years) | −0.063 | .95 | |||

| ≤35 | 25(8.4%) | 4 (6.1%) | 21 (9.1%) | ||

| 35–55 | 150(50.3%) | 36 (54.5%) | 114 (49.1%) | ||

| ≥55 | 123(41.3%) | 26 (39.4%) | 97 (41.8%) | ||

| Survival time | 39.48 ± 22.747 | 43.51 ± 23.327 | −1.166 | .244 | |

| Survival status and causes of death | −1.503 | .133 | |||

| Survived | 254(85.2%) | 52 (78.8%) | 202 (87.1%) | ||

| Died for BC | 32(10.7%) | 13 (19.7%) | 19 (8.2%) | ||

| Died for other causes | 12(4.0%) | 1 (1.5%) | 11 (4.7%) | ||

| Race | −0.351 | 0.726 | |||

| White | 226(75.8%) | 49 (74.2%) | 177 (76.3%) | ||

| Black | 26(8.7%) | 6 (9.1%) | 20 (8.6%) | ||

| Others | 46(15.4%) | 11 (16.7%) | 35 (15.1%) | ||

| T | −1.147 | .251 | |||

| T1 | 35(11.7%) | 4 (6.1%) | 31(11.7%) | ||

| T2 | 111(37.2%) | 23(34.8%) | 111(37.2%) | ||

| T3 | 128(43.0%) | 37(56.1%) | 128(43.0%) | ||

| Blank (Lost) | 24(8.1%) | 2(3.0%) | 24(8.1%) | ||

| N | −0.13 | .897 | |||

| N0 | 279(93.6%) | 62(93.9%) | 217(93.5%) | ||

| N1 | 8(2.7%) | 2(3.0%) | 6(75.0%) | ||

| Blank (Lost) | 11(3.7%) | 2(3.0%) | 9(3.9%) | ||

| M | −0.138 | .89 | |||

| MO | 294(98.7%) | 65(98.5%) | 229(98.7%) | ||

| M1 | 4(1.3%) | 1(1.5%) | 3(1.3%) | ||

| Tumor size | −2.458 | .014 | |||

| <50 | 166(55.7%) | 28(42.4%) | 138(59.5%) | ||

| ≥50 | 132(44.3%) | 38(57.6%) | 94(40.5%) | ||

| Tumor grade | −3.789 | 0 | |||

| G1 | 93(31.2%) | 9(13.6%) | 84(36.2%) | ||

| G2 | 61(20.5%) | 9(13.6%) | 52(22.4%) | ||

| G3 | 87(29.2%) | 33(50.0%) | 54(23.3%) | ||

| G4 | 57(19.1%) | 15(22.7%) | 42(18.1%) | ||

| Laterality | −0.466 | .641 | |||

| Left | 155(52.0%) | 36(54.5%) | 119(51.3%) | ||

| Right | 143(48.0%) | 30(45.5%) | 113(48.7%) | ||

| Number of positive lymph node biopsies | −0.468 | .64 | |||

| Negative | 295(98.9%) | 65(98.5%) | 230(99.1%) | ||

| Positive | 3(1.1%) | 1(1.5%) | 2(0.9%) | ||

| Surgery procedure | −1.816 | .069 | |||

| No surgery | 4(1.3%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (1.7%) | ||

| Mastectomy | 127(42.6%) | 36 (54.5%) | 91 (39.2%) | ||

| BCS | 167(56.0%) | 30 (45.5%) | 137 (59.1%) | ||

Abbreviation: BCS, breast-conserving surgery.

Survival Analysis

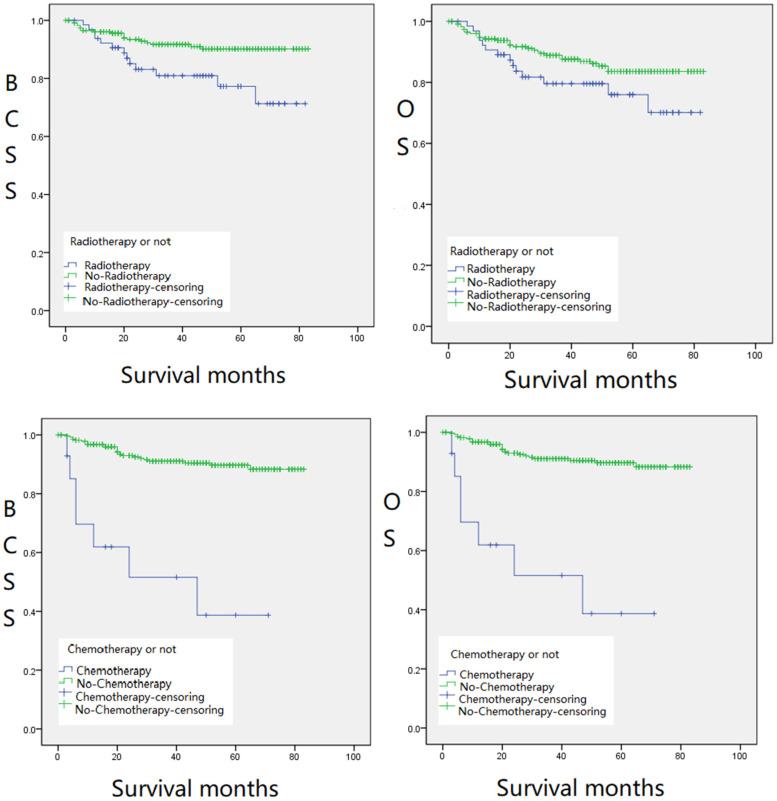

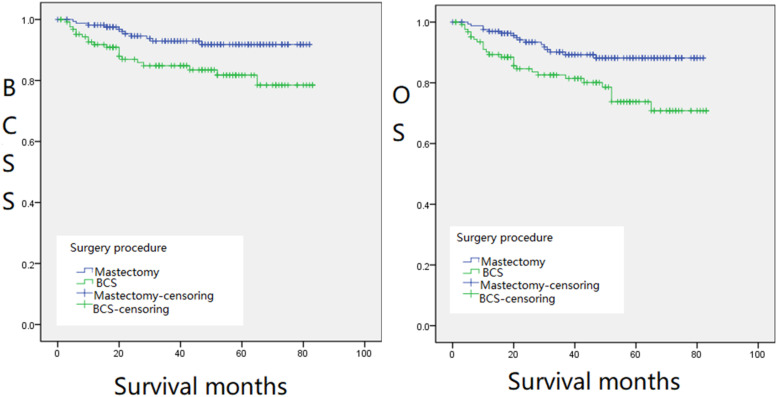

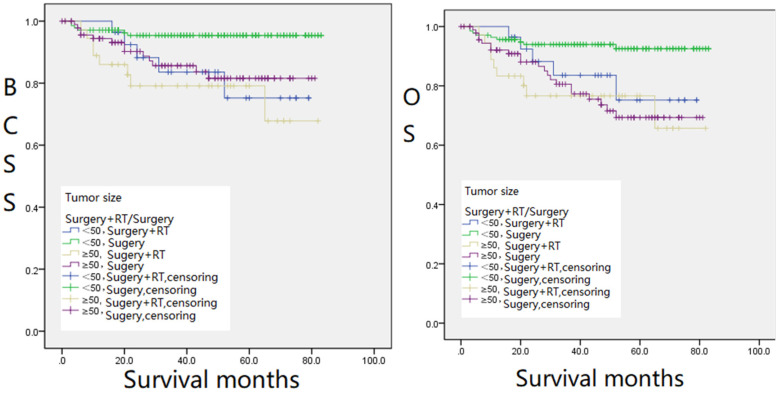

The 298 patients enrolled were divided into the following groups: RT and non-RT groups, CT and non-CT groups (Figure 1), BCS and mastectomy groups (Figure 2), and groups with different tumor sizes and treatments (Figure 3), Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was performed based on these groups. The 5-year BCSS was 78.9% and 90.0% for the RT and non-RT groups, respectively, and the 5-year OS was 78.9% and 82.3%, respectively, with logrank (Mantel–Cox) chi-square and P values of χ2 = 7.034, P = .008 and χ2 = 3.025, P = .082, respectively. The 5-year BCSS for the CT and non-CT groups was 38.2% and 89.7%, and the 5-year OS was 39.0% and 82.5%, respectively. logrank (Mantel–Cox) chi-square and P-values were: χ2 = 37.666, P = .000, and χ2 = 25.318, P = .000, respectively. The 5-year BCSS in the BCS and mastectomy groups was 82.1% and 91.0%, and 5-year OS was 73.8% and 86.9%, respectively, with logrank (Mantel–Cox) chi-square and P values of χ2 = 7.061, P = .008 and χ2 = 8.391, P = .004, respectively. The 5-year OS was statistically significant (P < .05) except for the RT and non-RT groups (P = .082) (Figures 1 and 2). We found that the survival of patients with RT or CT was significantly lower than that of the groups without therapies. In terms of surgical approaches, mastectomy was significantly better than BCS for the long-term survival of MPTB patients in both OS and BCSS (Figure 2). Notably, in terms of long-term survival, the survival rate of RT combined with surgery was worse than that of the surgery-only group, regardless of the size of the tumor. However, for patients with masses smaller than 50 mm, the survival rate of surgery combined with RT was better than that of the surgery-only group in the first 20 months after therapy; the former was 5% to 10% higher than the latter. This implies that for patients with tumor masses less than 50 mm, surgery combined with RT can be considered in the early treatment of the disease (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for BCSS (left,Figure 1(a)) and OS (right,Figure 1(b)) of radiotherapy (RT) and non-RT groups. Kaplan–Meier survival curves for BCSS (left,Figure 1(c)) and OS (right,Figure 1(d)) of chemotherapy (CT) and non-CT groups.

Abbreviations: BCSS, breast cancer-specific survival; OS, overall survival.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for BCSS (left,Figure 2(a)) and OS (right,Figure 2(b)) of BCS and mastectomy groups.

Abbreviations: BCSS, breast cancer-specific survival; OS, overall survival.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for BCSS (left,Figure 3(a)) and OS (right,Figure 3(b)) for different tumor sizes and treatments.

Abbreviations: BCSS, breast cancer-specific survival; OS, overall survival.

COX Regression Analysis

We identified prognostic factors in patients with MPTB: higher grade of tumor differentiation, larger tumor size, lymph node metastasis, whether RT was administered, and surgical approach were all associated with poorer clinical prognosis.

For OS, results from univariate Cox regression analysis (Table 2) displayed that race (P = .044, HR = 1.423, 95% CI = 1.010 to 2.004), T stage (P = .031, HR = 1.334, 95% CI = 1.026 to 1.733), distant metastasis (P = .000, HR = 129.997, 95% CI = 32.780 to 515.538), received CT or not (P = .087, HR = 0.574, 95% CI = 0.304,1.083), tumor size (P = .000, HR = 1.003, 95% CI = 1.001 to 1.005), tumor grade (P = .000, HR = 1.761, 95% CI = 1.325 to 2.342), number of positive lymph node biopsies (P = .000, HR = 2.496, 95% CI = 1.681 to 3.708), and surgical approach (P = .005, HR = 0.469, 95% CI = 0.028 to 0.797) were associated with poorer OS. Furthermore, outcomes from the multivariate Cox regression analysis (Table 3) exhibited that distant metastasis (P = .000, HR = 43.485, 95% CI = 5.953 to 317.655), received RT or not (P = .002, HR = 0.000, 95% CI = 0.000 to 0.012), received CT or not (P = .059, HR = 0.339, 95% CI = 0.111 to 1.042), surgery alone or surgery combined with RT (P = .002, HR = 47.097, 95% CI = 4.188 to 529.629), tumor grade (P = .001, HR = 1.797, 95% CI = 1.278 to 2.527), and number of positive lymph node biopsies (P = .000, HR = 3.288, 95% CI = 2.076 to 5.208) were independent risk factors for OS.

Table 2.

Univariate Cox Regression Analysis Affecting OS and BCSS in MPTB Patients.

| Variable | Univariate Cox analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OS | BCSS | |||

| P value | HR(95% CI) | P value | HR(95% CI) | |

| Age (years) | .211 | 1.373(0.835 to 2.258) | .541 | 1.195 (0.675 to 2.114) |

| Race | .044 | 1.423(1.010 to 2.004) | .013 | 1.625 (1.106 to 2.390) |

| T | .031 | 1.334 (1.026 to 1.733) | .141 | 1.266 (0.925 to 1.733) |

| N | .126 | 1.172 (0.956 to 1.437) | .149 | 1.188 (.940 to 0.501) |

| M | .000 | 129.997 (32.780 to 515.538) | .000 | 129.997 (32.780 to 15.538) |

| Surgery + RT/surgery | .110 | 0.840 (0.679 to 1.040) | .015 | 0.746 (0.588 to 0.945) |

| RT or not | .087 | 0.574 (0.304 to 1.083) | .011 | 0.398 (0.197 to 0.807) |

| Chemotherapy (CT) or not | .000 | 0.162 (0.072 to 0.366) | .000 | 0.113 (0.049 to 0.263) |

| Tumor size | .000 | 1.003 (1.001 to 1.005) | .001 | 1.003 (1.001 to 1.005) |

| Tumor grade | .000 | 1.761 (1.325 to 2.342) | .000 | 1.876 (1.332 to 2.644) |

| Laterality | .922 | 0.970 (0.537 to 1.754) | 0.602 | 1.203 (0.601 to 2.410) |

| Number of local lymph node biopsies | .127 | 1.016 (0.995 to 1.038) | 0.135 | 1.017 (0.995 to 1.040) |

| Number of positive results | .000 | 2.496 (1.681 to 3.708) | 0.000 | 2.534 (1.687 to 3.807) |

| Surgery procedure (mastectomy/BCS) | .005 | 0.469(0.028 to 0.797) | 0.007 | 0.424(0.227 to 0.791) |

Abbreviations: BCSS, breast cancer-specific survival; HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival; MPTB, malignant phyllodes tumor of the breast; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Table 3.

Multivariate Cox Regression Analysis Affecting OS and BCSS in MPTB Patients.

| Multivariate COX analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OS | BCSS | ||

| P value | HR(95% CI) | P value | HR(95% CI) | |

| Age (years) | .115 | 1.595 (0.892 to 2.851) | .302 | 1.442 (0.720 to 2.891) |

| Race | .962 | 1.010 (0.663 to 1.539) | .592 | 1.147 (0.694 to 1.896) |

| T | .181 | 1.280 (0.891 to 1.838) | .537 | 1.152 (0.735 to 1.805) |

| N | .843 | 1.027 (0.789 to 1.338) | .669 | 1.074 (0.775 to 1.489) |

| M | .000 | 43.485 (5.953 to 317.655) | .000 | 50.472 (6.028 to 422.608) |

| Surgery + RT/surgery | .002 | 47.097 (4.188 to 529.629) | .002 | 62.355 (4.748 to 818.937) |

| RT or not | .002 | 0.000 (0.000 to 0.012) | .001 | 0.000 (0.000 to 0.005) |

| Chemotherapy (CT) or not | .059 | 0.339 (0.111 to 1.042) | .014 | 0.235 (0.074 to 0.750) |

| Tumor size | .078 | 1.002 (1.000 to 1.005) | .031 | 1.003 (1.000 to 1.005) |

| Tumor grade | .001 | 1.797 (1.278 to 2.527) | .003 | 1.947 (1.259 to 3.013) |

| Laterality | .649 | 1.162 (0.609 to 2.218) | .309 | 1.506 (0.684 to 3.314) |

| Number of local lymph node biopsies | .998 | 1.000 (0.967 to 1.034) | .692 | 1.007 (0.972 to 1.044) |

| Number of positive results | .000 | 3.288 (2.076 to 5.208) | .000 | 3.492 (2.091 to 5.832) |

| Surgery procedure (mastectomy/BCS) | .933 | 0.961(0.381 to 2.422) | .475 | 0.716(0.286 to 1.790) |

Abbreviations: BCSS, breast cancer-specific survival; HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival; MPTB, malignant phyllodes tumor of the breast; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

For BCSS, univariate Cox regression analysis (Table 2) findings demonstrated that race (P = .013, HR = 1.625, 95% CI = 1.106 to 2.390), distant metastasis (P = .000, HR = 129.997, 95% CI = 32.780 to 15.538), surgery alone or surgery combined with RT (P = .015, HR = 0.746, 95% CI = 0.588 to 0.945), received CT or not (P = .000, HR = 0.113, 95% CI = 0.049 to 0.263), received RT or not (P = .011, HR = 0.398, 95% CI = 0.197 to 0.807), tumor size (P = .001, HR = 1.003 95% CI = 1.001 to 1.005), tumor grade (P = .000, HR = 1.876, 95% CI = 1.332 to 2.644), number of positive lymph node biopsies (P = 0.000, HR = 2.534, 95% CI = 1.687 to 3.807), and surgical approach (P = .007, HR = 0.424, 95% CI = 0.227 to 0.791) were associated with poor OS. Furthermore, multivariate Cox regression analysis (Table 3) showed that distant metastasis (P = .000, HR = 50.472, 95% CI = 6.028 to 422.608), surgery alone or surgery combined with RT (P = .002, HR = 62.355, 95% CI = 4.748 to 818.937), received CT or not (P = 0.014, HR = 0.235, 95% CI = 0.074 to 0.750), received RT or not (P = 0.001, HR = 0.000, 95% CI = 0.000 to 0.005), tumor size (P = .031, HR = 1.003, 95% CI = 1.000 to 1.005), tumor grade (P = 0.003, HR = 1.947, 95% CI = 1.259 to 3.013), and the number of positive lymph node biopsies (P = .000, HR = 3.492, 95% CI = 2.091 to 5.832) were independent risk factors for BCSS.

Discussion

MPTB accounts for a low proportion of neoplastic breast disease. Surgery is the primary treatment, but axillary lymph node dissection is not routinely performed because of its low incidence of axillary lymph node metastases. Negative margins are now considered an independent predictor of local recurrence after surgery; according to NCCN Guidelines, margins need to be at least 1 cm for borderline and MPTB and total mastectomy can be performed if necessary. 8 In terms of surgical approach, our survival analysis showed that BCS did not improve the long-term survival of patients diagnosed with MPTB; therefore, mastectomy is usually recommended for patients without specific requirements. In patients with recurrent disease who has received BCS, secondary surgery requires an extended excision or total mastectomy. Other factors must also be considered to maximize the survival rate.14,15 Univariate Cox regression analysis of this study exposed (Table 2) that there was a statistically significant difference between surgical approach on OS (P = .005, HR = 0.469, 95% CI = 0.028 to 0.797) and BCSS (P = .007, HR = 0.424, 95% CI = 0.227 to 0.791). Our survival analysis also showed (Figure 2a and b) that patients who underwent mastectomy had higher BCSS and OS than BCS. In conjunction with previous studies, Pezner et al 16 studied 478 patients of malignant phyllodes tumors (PT) with local recurrence and reported that the local recurrence rates were higher for patients treated with BCS (20.6%) than those treated with mastectomy (8.8%), and breast preservation (or its absence) does not affect local recurrence rates. However, Edwin et al 17 analyzed 67 patients with PT, including borderline PT (15 patients) and MPTB (52 patients), concluding that the extent of surgical excision had no significant effect on BCSS of PTB. However, the latter conclusion was based on the analysis of borderline and malignant tumors together and therefore had no absolute reference value for the factors influencing BCSS in patients with MPTB. Yazid et al 7 studied 443 patients with PTB, including 284 benign tumors (64%), 80 borderline tumors (18%), and 79 malignant tumors (18%), and concluded that mastectomy was superior to BCS for both borderline and malignant tumors. Therefore, in concurrence with this study, mastectomy is the first option to be considered for MPTB patients who do not opt for breast conservation. For patients to undergo BCS, the surgical margins should be at least 1 cm to reduce the risk of local recurrence.7,18 The surgical approach and surgical margin size are 2 important factors in recurrence.

Regarding RT, our survival analysis displayed (Figure 1a, b, c, and d) that neither RT nor CT had a significant effect on the long-term survival of MPTB patients. The non-RT group had higher BCSS (P = .008) and OS (P = .082) than the RTgroup. Similarly, the non-CT group also had higher BCSS (P = .000) and OS (P = .000) than the CT group. However, there was no statistically significant difference in OS between the non-RT group and the RT group (P = .082). Multivariate Cox regression analysis of this study demonstrated (Table 3) that RT and CT were independent risk factors for BCSS (P = .002 in the RT group and P = .001 in the CT group) and OS (P = .002 in the RT group and P = .002 in the CT group). Similar results have been verified in the previous literature. Belkacémi et al 7 reported that postoperative RT improved the 10-year local control rate in the borderline and malignant PT groups but did not affect OS. Confavreux et al 19 found that RT had no significant effect on the long-term survival rate of patients with MPTB, and unnecessary RT was even harmful to patients. Therefore, the therapeutic status of RT in patients with MPTB should be reduced. 20 However, adjuvant RT is still relevant in patients with MPTB having recurrence after the initial surgery. Kim et al21,22 analyzed patients who underwent a mastectomy and BCS, in which 130 (16%) and 122 (11%) patients in the 2 groups received postoperative RT, respectively, and discovered that the BCSS in the RT group was not lower than that in the non-RT group, regardless of whether surgery was performed (mastectomy or BCS), which is also consistent with our results. Nevertheless, some investigators have also suggested different opinions. Barth et al 9 revealed that adjuvant RT is an effective method to control the local recurrence of borderline and malignant PT after BCS. The recurrence rate was significantly reduced after adjuvant RT in patients with negative margins.

There are also few references indicating that CT is meaningful for the long-term survival of MPTB patients. However, Mauro determined 20 that RT could improve MPTB survival based on the premise of tumor metastasis, which rarely occurs in MPTB. Consequently, the effect of RT on the long-term survival of patients with MPTB is currently held by different scientific communities. Still, this study found that neither RT nor CT had a significant effect on the long-term survival of patients with MPTB, which has been acknowledged by many scholars as well.

Interestingly, our data showed no significant benefit in long-term survival for MPTB with either RT or CT. In terms of early survival, patients with masses less than 50 mm OS (P = .003) and BCSS (P = .029) were significantly better in the surgery combined with RT than in the surgery alone group (Figure 3a and b). This proposes that surgery combined with RT may be considered in treating patients with masses less than 50 mm in the early stages of the disease. Pezner et al 16 also noted that the value of adjuvant RT was significantly increased in patients with locally resected tumors > 2 cm and post-mastectomy tumors > 10 cm. In conclusion, the survival analysis of this study suggests that neither RT nor CT can significantly improve the long-term survival of patients with MPTB. However, for patients with masses less than 50 mm, RT can improve their OS and BCSS at an early stage, which is critical in improving the quality of survival and the psychological condition of patients with MPTB.

There are several limitations of this study. First, the patients treated with combined RT and CT exhibiting poorer survival also had a worse tumor prognosis at presentation:72% of the patients who underwent RT presented with grades G3 and G4, while only 41% of the patients who did not undergo RT were G3 and G4 at presentation. It is possible that uniform poor histologic features of marked stromal atypia, high mitotic count, and necrosis of the patient indicated a worse prognosis. Furthermore, tumors in these groups were predominantly over 50 mm (poor prognosis), and there was no mention of chest wall invasion. Second, although the SEER database has a classification for PT (9020/1), only patients with malignant PT were registered in this database. Misdiagnosis of borderline tumors as the malignant disease may have affected the outcome of the analysis, which led to a better prognosis than expected from other clinical studies.23,24 Pathological information of tumor tissue is not available, which requires continuous improvement of the database. Therefore, multiple endpoints based on additional clinicopathologic data must be studied to analyze the clinical benefit of RT for MPTB accurately. However, the accuracy of SEER, one of the largest population-based analysis databases, cannot be ignored for its great content.

Conclusions

The findings of this study suggest that BCS does not improve long-term patient survival and that mastectomy remains the preferred treatment procedure for patients with MPTB. In addition, adjuvant RT and CT did not improve BCSS or OS in patients with MPTB. However, for tumors less than 50 mm in diameter, early RT has some significance for early patient survival, but this still requires further clinical cohort studies.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Tongji University for providing equipment and excellent technical support for our study. We thank Home for Researchers (www.home-for-researchers.com) for language polishing.

Abbreviations

- BSC

breast-conserving surgery

- BCSS

breast cancer-specific survival

- CT

chemotherapy

- HRs

hazard ratios

- MPTB

malignant phyllodes tumor of the breast

- OS

overall survival

- PT

phyllodes tumor

- PTB

phyllodes tumor of the breast

- RT

radiotherapy

- SEER

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results

- USA

United States of America

- WHO

World Health Organization

- 95% CIs

95% confidence intervals

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The present study was supported by the Shanghai Yangpu District Health and Family Planning Commission Fund for Hao Yi Shi Training Project (Grant Nos. 201742 and 2020-2023) and the Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (Grant No. 18ZR1436000).

ORCID iDs: Hongyi Zhang https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9164-9072

Fengfeng Cai https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7390-1673

References

- 1.Varghese C, Shin HR. Strengthening cancer control in China. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(5):484-485. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70056-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mituś J, Reinfuss M, Mituś JWet al. et al. Malignant phyllodes tumor of the breast: treatment and prognosis. Breast J. 2014;20(6):639-644. doi: 10.1111/tbj.12333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pacioles T, Seth R, Orellana C, John I, Panuganty V, Dhaliwal R. Malignant phyllodes tumor of the breast presenting with hypoglycemia: a case report and literature review. Cancer Manag Res. 2014;6:467-473. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S71933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guillot E, Couturaud B, Reyal Fet al. Management of phyllodes breast tumors. Breast J. 2011;17(2):129-137. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2010.01045.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawkins RE, Schofield JB, Fisher C, Wiltshaw E, McKinna JA. The clinical and histologic criteria that predict metastases from cystosarcoma phyllodes. Cancer-Am Cancer Soc. 1992;69(1):141-147. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Macdonald OK, Lee CM, Tward JD, Chappel CD, Gaffney DK. Malignant phyllodes tumor of the female breast: association of primary therapy with cause-specific survival from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program. Cancer-Am Cancer Soc. 2006;107(9):2127-2133. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belkacémi Y, Bousquet G, Marsiglia Het al. Phyllodes tumor of the breast. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70(2):492-500. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.06.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reinfuss M, Mituś J, Duda K, Stelmach A, Ryś J, Smolak K. The treatment and prognosis of patients with phyllodes tumor of the breast: an analysis of 170 cases. Cancer-Am Cancer Soc. 1996;77(5):910-916. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barth RJ, Wells WA, Mitchell SE, Cole BF. A prospective, multi-institutional study of adjuvant radiotherapy after resection of malignant phyllodes tumors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:2288-2294. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0489-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaney AW, Pollack A, McNeese MDet al. et al. Primary treatment of cystosarcoma phyllodes of the breast. Cancer-Am Cancer Soc. 2000;89(7):1502-1511. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gnerlich JL, Williams RT, Yao K, Jaskowiak N, Kulkarni SA. Utilization of radiotherapy for malignant phyllodes tumors: analysis of the national cancer data base, 1998-2009. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:1222-1230. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3395-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang H, Lin X, Huang Yet al. Detection methods and clinical applications of circulating tumor cells in breast cancer. Front Oncol. 2021;11:652253. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.652253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang H, Zhang H, Zhu Y, Wu Z, Cui C, Cai F. Anticancer mechanisms of salinomycin in breast cancer and its clinical applications. Front Oncol. 2021;11:654428. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.654428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andre F, Slimane K, Bachelot Tet al. Breast cancer with synchronous metastases: trends in survival during a 14-year period. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(16):3302-3308. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soran A, Ozmen V, Ozbas Set al. Randomized trial comparing resection of primary tumor with No surgery in stage IV breast cancer at presentation: protocol MF07-01. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25:3141-3149. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-6494-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pezner RD, Schultheiss TE, Paz IB. Malignant phyllodes tumor of the breast: local control rates with surgery alone. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71(3):710-713. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.10.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Onkendi EO, Jimenez RE, Spears GM, Harmsen WS, Ballman KV, Hieken TJ. Surgical treatment of borderline and malignant phyllodes tumors: the effect of the extent of resection and tumor characteristics on patient outcome. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:3304-3309. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3909-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klassen AF, Pusic AL, Scott A, Klok J, Cano SJ. Satisfaction and quality of life in women who undergo breast surgery: a qualitative study. Bmc Womens Health. 2009;9:11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-9-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Confavreux C, Lurkin A, Mitton Net al. Sarcomas and malignant phyllodes tumours of the breast–a retrospective study. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42(16):2715-2721. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.05.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mauro GP, de Andrade CH, Stuart SR, Mano MS, Marta GN. Effects of locoregional radiotherapy in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Breast. 2016;28:73-78. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim YJ, Kim K. Radiation therapy for malignant phyllodes tumor of the breast: an analysis of SEER data. Breast. 2017;32:26-32. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2016.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim YJ, Jung SY, Kim K. Survival benefit of radiotherapy after surgery in de novo stage IV breast cancer: a population-based propensity-score matched analysis. Sci Rep. 2019;9:8527. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-45016-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kapiris I, Nasiri N, A'Hern R, Healy V, Gui GP. Outcome and predictive factors of local recurrence and distant metastases following primary surgical treatment of high-grade malignant phyllodes tumours of the breast. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2001;27(8):723-730. doi: 10.1053/ejso.2001.1207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Roos WK, Kaye P, Dent DM. Factors leading to local recurrence or death after surgical resection of phyllodes tumours of the breast. Br J Surg. 1999;86(3):396-399. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1999.01035.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]