Abstract

Phase variation of flagellin gene expression in Campylobacter coli UA585 was correlated with high-frequency, reversible insertion and deletion frameshift mutations in a short homopolymeric tract of thymine residues located in the N-terminal coding region of the flhA gene. Mutation-based phase variation in flhA may generate functional diversity in the host and environment.

Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli are now recognized as the commonest causal agents of acute bacterial enteritis worldwide (23). The spiral shape and the characteristic motility, imparted by a single polar flagellum, of these bacteria are important in their ability to colonize the viscous mucous blanket lining the intestinal tract (14). The immune response mounted against the Campylobacter flagella leads to partial protection against challenge by this pathogen (19), and consequently, events which lead to the loss of the flagellum may provide campylobacters with a mechanism to escape the host immune response. Such events would also allow the cell to save energy under circumstances where motility is not necessary. In this context, some strains of Campylobacter have been shown to undergo both antigenic variation of flagellum expression (6) and phase variation, involving the bidirectional transition between flagellate and aflagellate phenotypes (2, 5, 15, 17). Since the basis for this variation is unknown we sought to characterize the genetic mechanisms governing this process in C. coli.

Isolation of nonmotile phase variants.

C. coli UA585, originally isolated from a diarrheic pig, was a generous gift from D. E. Taylor (University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada). Phase variants of C. coli UA585 were isolated as described previously (15). After incubation of the phase variants in Luria-Bertani broth (21) for 48 h at 42°C, plate counts derived from the cultures revealed equal numbers of motile (large, swarming morphology) and nonmotile (pinpoint morphology) colonies. After isolation the nonmotile phase variants could be maintained as stable cultures. One such nonmotile phase variant designated C. coli NM3 was chosen for further study.

When cells of C. coli UA585 were grown to exponential phase in Mueller-Hinton broth (Oxoid-Unipath, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) and assessed for phase variation as described above, the flagellate to aflagellate transition occurred at a rate of 3 × 10−4 per cell. Transition from the nonmotile to motile phenotype during exponential growth occurred at a rate of 7 × 10−6 per cell.

flaA transcription and flaB transcription are repressed in nonmotile phase variants.

Expression of both FlaA and FlaB, constituting the Campylobacter flagellin, in the nonmotile phase variant NM3 was monitored by using a hipO reporter of gene expression (18). Accordingly, gene fusions, to both flaA and flaB, were constructed with the fla-hipO integrational vector pHIP108 (18). The nature of the integrative event in the transformants derived from pHIP108 and NM3 was confirmed by PCR with the discriminatory primers FLA1 and FLAB (18). Strains of C. coli NM3 in which pHIP108 had integrated into either flaA or flaB were designated CCSFP1231 and CCSFP1241, respectively.

Strains CCSFP1211 and CCSFP1221, which contain flaA- and flaB-hipO fusions and are derived from the motile parental strain C. coli UA585 (18), gave rise to 42 and 7.8 U of hippuricase activity, respectively, when expression from the marker gene fusions was assessed (Table 1). The 5.3-fold difference in levels of expression from flaA and flaB was expected and has been discussed previously (9, 16, 18). Levels of expression from the flaA- and flaB-hipO fusions in the nonmotile variant C. coli NM3 were 13- and 16-fold lower, respectively, than those monitored from the corresponding fusions in the motile parental strain. However, in control experiments, when hipO expression from the same constitutively expressed hipO fusion, present in either the nonmotile variant CCHP21 or the parental strain (CCHP20) (18), was measured, hippuricase activity was expressed at broadly equivalent levels. Thus, the repression of flaA and flaB expression in C. coli NM3 is a consequence of genetic events which lead to the specific reduction in transcription from both flaA and flaB.

TABLE 1.

Expression of hippuricase activity in various strains of C. coli

| Strain | Genetic characteristics | Hippuricase activitya |

|---|---|---|

| UA585 | Motile parental strain, no hipO fusion | 0.11 |

| NM3 | Nonmotile variant, no hipO fusion | 0.13 |

| CCHP20 | Motile parental strain with a constitutive hipO fusion | 2.3 |

| CCHP21 | Nonmotile variant with a constitutive hipO fusion | 2.8 |

| CCSFP1211 | Motile parental strain with a flaA-hipO fusion | 42 |

| CCSFP1221 | Motile parental strain with flaB-hipO fusion | 7.8 |

| CCSFP1231 | Nonmotile parental strain with a flaA-hipO fusion | 3.2 |

| CCSFP1241 | Nonmotile parental strain with flaB-hipO fusion | 0.2 |

Hippuricase activity was assessed in cells grown in Mueller-Hinton broth and is expressed as the optical density at 570 nm from the hippuricase assay divided by the optical density at 600 nm of the culture from which the cells were derived (18). Similar results were reproducibly obtained in at least two sets of experiments.

Genetic complementation of the locus conferring nonmotility.

We next sought to identify the locus conferring phase variability to flagellin gene expression, using a genetic complementation strategy. Genomic libraries based in Campylobacter shuttle plasmids proved unsuitable for this purpose, as the plasmids were unstable in C. coli. Consequently, we developed a novel procedure to allow the complementation of the motility mutation. We reasoned that if the integrational vector pSP105 (4) were integrated randomly into the chromosome of the motile parental strain of C. coli, then in some transformants the integration of the plasmid would occur proximal to the locus that confers motility to the parental strain but is altered in the nonmotile variant. In effect, this would locate a tetracycline antibiotic resistance marker close to the corresponding locus. Thus, if chromosomal DNA derived from a library of pSP105 integrants were used to transform the nonmotile variant NM3, any resulting transformants which had acquired tetracycline resistance and, concomitantly, motility should have been derived from transforming DNA in which the antibiotic marker was closely linked to the locus controlling motility.

A library was generated by introducing BglII-digested C. coli UA585 chromosomal DNA into the corresponding BamHI site of the integrational vector pSP105 (4). The library was then introduced into the same strain by natural transformation, and 5.2 × 105 transformants were recovered. These transformants were pooled, and the chromosomal DNA, containing randomly integrated pSP105 derivatives, was extracted. This DNA was next introduced into C. coli NM3 by natural transformation. Subsequently, a number of transformants that both were tetracycline resistant and displayed motility were recovered. One transformant in which tetracycline resistance was clearly linked to the ability to confer motility was designated CCNMR7 and chosen for further study.

Identification of the mutational basis governing phase variability.

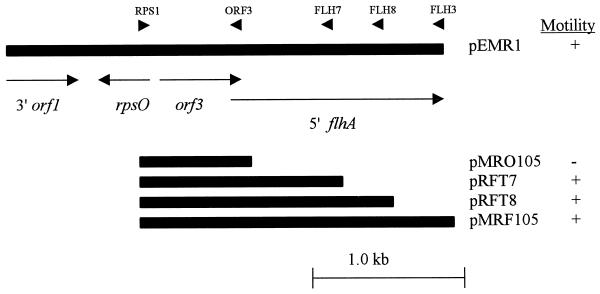

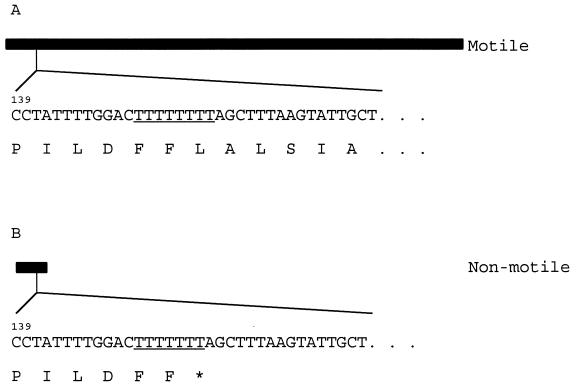

Plasmid DNA containing the sequences flanking the site of integration in CCNMR7 was resolved directly from chromosomal DNA by using NcoI as has been described previously (4, 20). Subsequently, a series of subcloning experiments, using pSP105 as the cloning vector, localized the locus affecting motility to a 3.0-kb EcoRI fragment contained in pEMR1 (Fig. 1). The nucleotide sequence of the DNA insert in this vector was determined and found to correspond to a region of DNA containing the flhA gene which has been characterized previously in C. jejuni (12, 13). Since this region contains four open reading frames, the locus responsible for controlling motility in the phase variants was localized by PCR-based cloning strategy (Fig. 1). DNA fragments generated by PCR using chromosomal DNA from the motile parental strain as the template were cloned into the integrational vector pSP105, and the ability of the resulting constructs to confer motility to C. coli NM3 was assessed. In this manner, a 415-bp fragment of DNA, internal to the flhA gene, was found to restore motility to the nonmotile variant NM3. As a control to rule out PCR artifacts this region was amplified by PCR with the primers RPS1 and FLH7 (Fig. 1), chromosomal DNA from both the motile parental strain and the nonmotile variant, and three separate reactions to generate fragments for each chromosomal target. The resulting fragments were cloned into pSP105 to generate the derivatives pRFT7.1 to -3 and pRNT7.1 to -3, respectively. These plasmids were next introduced into nonmotile derivative C. coli NM3, and the effects on the phenotype were assessed. As anticipated, the plasmids pRFT7.1 to -3, but not pRNT7.1 to -3, conferred motility to this strain, confirming that the DNA inserts represented the chromosomal DNA sequences responsible for the corresponding motility status of the strains from which the fragments were originally amplified. Analysis of the inserted DNA sequences, derived from the motile parental strain, in all three pRFT7 derivatives revealed the presence of a poly T tract containing eight T residues 148 bp downstream of the ATG translational start. In comparison, analysis of the inserted DNA sequences in all three pRNT7 derivatives, containing DNA derived from the nonmotile variant C. coli NM3, showed the sequences to be identical to those obtained from the motile parental strain, except for the presence of a deletion, resulting in only seven T residues in the poly T tract. This deletion results in the formation of an in-frame TAG stop causing the premature termination of flhA and the consequent abrogation of its expression (Fig. 2). A revertant motile variant derived from C. coli NM3 was also shown to have corrected the deletion and had restored the poly T tract to eight residues (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Localization of the locus responsible for phase-variation in C. coli. The plasmid pEMR1 contains a 3.0-kb EcoRI insert from the C. coli UA585 chromosome that confers motility to the nonmotile phase variant NM3. PCR was used to amplify DNA fragments corresponding to the various parts of the flhA region. The sites for primer binding are designated by arrowheads. The primers used were RPS1 (5′ GGATCCGGCCGAATCCAAAGCCATGATAGA 3′), ORF3 (5′ GGATCCCCAACAATAGTCAAGCTTTTAGCT 3′), FLH3 (5′ GGATCCTAAAATTTCAACTTTGAGTATATCGTT 3′), FLH7 (5′ GGATCC TTTGTTTACCCGGCATCGCATCAA 3′), and FLH8 (5′ GGATCC CCTCATCTTTGCTTGCACCAGTGA 3′). All PCR products were cloned into the integrative vector pSP105 as BamHI fragments. The ability of the corresponding plasmids to confer motility was assessed by introducing them into strain MN3 by natural transformation, and each plasmid was determined to be motile (+) or nonmotile (−).

FIG. 2.

Mutational basis generating phase variation of FlhA expression. Two versions of the FlhA protein as derived from C. coli UA585 (A) and NM3 (B) are represented by the bars. Below each representation of the protein is the nucleotide sequence which governs its expression. The poly T tract underlined results in expression of either full-length FlhA (eight T's) or a truncated version (seven T's) as a consequence of the deletion of a single T residue, resulting in the generation of an in-frame termination codon. The nucleotides are numbered from the ATG start of flhA. The nucleotide sequences corresponding to flhA containing poly T tracts of eight and seven residues appear in the GenBank database under accession no. AF171083 and AF171084, respectively.

Conclusion.

High-frequency phase variation of flagellin gene expression in C. coli UA585 was correlated with insertion and deletion mutations in a short poly T tract in the flhA gene. FlhA is a member of the LcrD/FlbF family, whose members are all integral cytoplasmic membrane proteins involved in the regulation or secretion of surface or extracellular proteins (7). In particular, mutations in flhA homologues result in the loss of expression of flagellin-related genes. Indeed, inactivation of this gene in C. jejuni resulted in the failure to synthesize flagellin (13). It is clear from the present study that inactivation of the flhA gene can occur naturally by a localized frameshift mutation which leads to nonmotility in C. coli, and that this phenotype is, at least partly, a consequence of the failure of cells to transcribe either flaA or flaB. The precise function of FlhA is unknown, and it is not clear whether its involvement in controlling the motility of cells is direct or indirect. In Salmonella typhimurium, for example, regulation of flagellin gene expression may be coupled to the expression of other components involved in flagellum formation (8). Consequently, mutations in genes encoding proteins in the flagellum basal body or switch complex lead indirectly to the repression of flagellin genes. In contrast, in Helicobacter pylori, which is closely related to C. coli, while inactivation of the flhA gene leads to repression of FlaA and FlaB expression, the mechanism of this inactivation is thought to be independent of the feedback mechanism described above for S. typhimurium, and accordingly, a more direct role for FlhA in the regulation of expression of flagellum components is envisaged (21).

Whichever mechanism leads to the abrogation of flaA and flaB expression, it is clear that the end result is a significant reduction in macromolecular synthesis within the cell and a conservation of its biosynthetic capacity under circumstances when motility is not necessary. Furthermore, flagellum phase variation may provide C. coli with the possibility of escaping the host immune response against the flagellum.

Translational variation caused by frameshift mutations has been shown to be a widespread mechanism for generating selective phase variation in virulence-associated products in a number of bacterial pathogens (3, 11, 24, 26). This is the first report demonstrating that this process also operates to generate functionally variant cells in campylobacters. Interestingly, the flhA gene sequences of C. jejuni 81-176 (12, 13) and NCTC 11168 (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/C_jejuni) do not contain the eight-T homopolymeric tract of the C. coli gene sequence, and consequently phase variation of flagellin gene expression in this species may occur by a different mechanism.

Given the high A+T ratio of the Campylobacter spp. (1) it is likely that the genome contains numerous poly A/T tracts and that, therefore, localized hypermutation in short homopolymeric tracts is a process which operates at a number of other sites on the C. coli genome. Indeed, a preliminary analysis of the genome sequence of C. jejuni, a close relative of C. coli, reveals the presence of at least 25 polymorphic regions that correspond to repeat structures, which may represent potential frameshift mutator elements (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/C_jejuni). The presence of these short sequence repeats may, in part, contribute to the high degree of phenotypic and genomic variability reported for campylobacters (25). The frequency of slipped-strand mispairing, and thus mutation at these sequences, may also be influenced by DNA repair systems. For instance, Escherichia coli strains with mutations in mismatch repair activity are more prone to strand slippage events (10). The presence of a MutS homologue in C. jejuni, as indicated by analysis of the genome sequence (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/C_jejuni), suggests that the capacity for mismatch repair exists. At present, however, it is not clear whether this operates in all strains and what effect it has on the frequency of phase variation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Belland R J, Trust T J. Deoxyribonucleic acid sequence relatedness between thermophilic members of the genus Campylobacter. J Gen Microbiol. 1982;128:2515–2522. doi: 10.1099/00221287-128-11-2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caldwell M B, Guerry P, Lee E C, Burans J P, Walker R I. Reversible expression of flagella in Campylobacter jejuni. Infect Immun. 1985;50:941–943. doi: 10.1128/iai.50.3.941-943.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen C J, Elkins C, Sparling P F. Phase variation of hemoglobin utilization in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect Immun. 1998;66:987–993. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.987-993.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dickinson J H, Grant K A, Park S F. Targeted and random mutagenesis of the Campylobacter coli chromosome using integrational plasmid vectors. Curr Microbiol. 1995;31:92–96. doi: 10.1007/BF00294282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diker K S, Hascelik G, Akan M. Reversible expression of flagella in Campylobacter spp. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;78:261–264. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90037-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doig P, Kinsella N, Guerry P, Trust T J. Characterization of a post-translational modification of Campylobacter flagellin: identification of a sero-specific glycosyl moiety. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:379–387. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.370890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galan J E, Ginocchio C, Costeas P. Molecular and functional characterization of the Salmonella invasion gene invA: homology of InvA to members of a new protein family. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4338–4349. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.13.4338-4349.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gillen K L, Hughes K T. Negative regulatory loci coupling flagellin synthesis to flagellar assembly in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2301–2310. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.7.2301-2310.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guerry P, Logan S M, Thornton S, Trust T J. Genomic organization and expression of Campylobacter flagellin genes. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:1853–1860. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.4.1853-1860.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henderson I R, Owen P, Nataro J P. Molecular switches—the ON and OFF of bacterial phase variation. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:919–932. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jonsson A B, Nyberg G, Normark S. Phase variation of gonococcal pili by frameshift mutation in pilC, a novel gene for pilus assembly. EMBO J. 1991;10:477–488. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07970.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller S, Pesci E C, Pickett C L. Genetic organization of the region upstream from the Campylobacter jejuni flagellar gene flhA. Gene. 1994;146:31–38. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90830-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller S, Pesci E C, Pickett C L. A Campylobacter jejuni homologue of the LcrD/FlbF family of proteins is necessary for flagellar biogenesis. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2930–2936. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.7.2930-2936.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morooka T, Umeda A, Amako K. Motility as an intestinal colonization factor for Campylobacter jejuni. J Gen Microbiol. 1985;131:1973–1980. doi: 10.1099/00221287-131-8-1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nuijten P J, Marquez-Magana L, van der Zeijst B A. Analysis of flagellin gene expression in flagellar phase variants of Campylobacter jejuni 81116. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1995;67:377–383. doi: 10.1007/BF00872938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nuijten P J, van Asten F J, Gaastra W, van der Zeijst B A. Structural and functional analysis of two Campylobacter jejuni flagellin genes. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:17798–17804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nuijten P J, Bleumink-Pluym N M, Gaastra W, van der Zeijst B A. Flagellin expression in Campylobacter jejuni is regulated at the transcriptional level. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1084–1088. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.4.1084-1088.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park S F. The use of hipO, encoding benzoylglycine amidohydrolase (hippuricase), as a reporter of gene expression in Campylobacter coli. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1999;28:285–290. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pavlovskis O R, Rollins D M, Haberberger R L, Jr, Green A E, Habash L, Strocko S, Walker R I. Significance of flagella in colonization resistance of rabbits immunized with Campylobacter spp. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2259–2264. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.7.2259-2264.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richardson P T, Park S F. Enterochelin uptake in Campylobacter coli: characterisation of components of a binding protein-dependent transport system. Microbiology. 1995;141:3181–3191. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-12-3181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmitz A, Josenhans C, Suerbaum S. Cloning and characterization of the Helicobacter pylori flbA gene, which codes for a membrane protein involved in coordinated expression of flagellar genes. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:987–997. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.4.987-997.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tauxe R V. Epidemiology of Campylobacter jejuni in the United States and other industrialized nations. In: Nachamkin I, Blaser M J, Tompkins L S, editors. Campylobacter jejuni: current status and future trends. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1992. pp. 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Theiss P, Wise K S. Localized frameshift mutation generates selective, high-frequency phase variation of a surface lipoprotein encoded by a mycoplasma ABC transporter operon. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4013–4022. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.12.4013-4022.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wassenaar T M, Geilhausen B, Newell D G. Evidence of genomic instability in Campylobacter jejuni isolated from poultry. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1816–1821. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.5.1816-1821.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Q, Wise K S. Localized reversible frameshift mutation in an adhesin gene confers a phase-variable adherence phenotype in mycoplasma. Mol Microbiol. 1997;125:859–869. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1997.mmi509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]