In light of the continuing coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, virtual interviews will continue in the upcoming 2022 Electronic Residency Application Services cycle. As such, it is essential to recognize and learn from the experiences of the previous application cycle. The authors’ study collected comprehensive data regarding the virtual residency interview process through a combined quantitative and qualitative approach. They provide principles and recommendations to both programs and applicants for the upcoming interview season.

Key Words: COVID-19, residency application, virtual interview

Abstract

Objectives

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has had a profound impact on medical education at all levels, particularly on applicants applying to residency programs. The objective of the study was to gain a comprehensive understanding of applicants’ perspectives on virtual interviews in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

We conducted a quantitative survey and a qualitative study between March and April 2021. The link to an anonymous online survey was emailed to fourth-year medical students from one allopathic medical school. The survey link also was posted on the social media page of one allopathic medical school and one osteopathic medical school. Participants were then invited to participate in a follow-up 15- to 45-minute qualitative virtual interview.

Results

A total of 46 participants completed the survey, with a response rate of approximately 29.1%. The most beneficial aspect of the virtual interview was saving money on travel (31, 78.39%). In contrast, the least beneficial aspect of the virtual interview was the inability to personally explore the culture of the program (16, 34.78%), followed by the inability to explore the city and surrounding area (11, 23.91%). Thematic saturation was reached after interviewing 14 participants over Zoom. Four major themes of the virtual residency interview experience were discussed: virtual interviews offered many advantages, virtual interviews posed unique challenges, residency programs need more organizational improvements, and virtual specific preparations are needed.

Conclusions

Despite the challenges associated with the virtual interview process, applicants rated the overall virtual interview experience positively. Given the continued impact of COVID-19 on medical education, the majority of residency programs will elect to continue virtual interviews for the 2022 Electronic Residency Application Services cycle. We hope that our findings may provide insight into the applicant’s perspective on the virtual interview experience and help optimize virtual interviews for future cycles.

Key Points

The most beneficial aspect of the virtual interview was saving money on travel.

In contrast, the least beneficial aspect of the virtual interview was the inability to personally explore the culture of the program followed by the inability to explore the city and surrounding area.

Four major themes of the virtual residency interview experience were virtual interviews offered many advantages, virtual interviews posed unique challenges, residency programs need more organizational improvements, and virtual specific preparations are needed.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has a profound impact on medical education at all levels, particularly those applying for residency programs. All of the applicants in the 2021 Electronic Residency Application Services (ERAS) cycle participated in an entirely unprecedented virtual interview format that posed unique challenges to applicants and training programs.

A residency interview is a critical part of the Match process. It provides an opportunity for applicants to showcase their personality, interpersonal skills, and achievements and to gauge the culture of the program. The traditional face-to-face interview day provides valuable interactions with faculty and residents from the program and allows applicants to assess the overall culture and fit of the program.1 The actual interview day heavily influences applicants’ rank lists.2 Because of the COVID-19 public health crisis, however, residency programs have had to adapt to a virtual format to provide applicants with the information and impressions they would typically receive during the traditional face-to-face interview days. This transformation required a fundamental change to the interview process for both applicants and residency programs.

Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic continues, and various organizations have recommended that residency programs continue virtual interviews for the next application cycle.3 To develop a comprehensive understanding of the applicant experience during virtual interviews for the 2021 Match season, we conducted both a qualitative study and a quantitative study. We hope to further optimize the virtual interview processes to help applicants adequately convey their desired impressions and make informed decisions in ranking and choosing their future residency programs.

Methods

We conducted a combined quantitative survey and a qualitative study between March and April 2021 to gain a comprehensive understanding of residency applicants’ experiences during the virtual residency interview process. The phenomenology approach to qualitative study was used to capture the applicants’ collective experience, to determine the common themes, and to develop a universal essence based on these similarities.4

Study Design

A survey-based study consisted of a 30-question anonymous survey developed using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCAP, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN) database.5 The survey was pilot tested for reliability and validity by two fourth-year medical students. The link to an anonymous online survey was emailed to fourth-year medical students from one allopathic medical school, and the survey link was posted on the social media page of one allopathic medical school and one osteopathic medical school. Students were invited to disseminate the survey to their colleagues using a snowball sample approach. Weekly, three follow-up e-mails were sent out as a reminder to participants. Participation was voluntary, and participants were allowed to terminate the survey at any time. In the survey, the participants were asked whether they would like to participate in the follow-up qualitative interview. Participants were asked to provide their e-mail addresses if they agreed to participate, and an author (E.L.) contacted them to set up a Zoom interview.

The inclusion criteria for the qualitative study were fourth-year medical students who participated in virtual residency interviews during the 2020–2021 residency cycle. After obtaining verbal consent, one 15- to 45-minute semistructured interview was conducted over Zoom (Zoom Video Communications, San Jose, CA).6 The semistructured interview questions were developed to capture the applicants’ experience during virtual residency interviews (Supplemental Digital Content Appendix 1, http://links.lww.com/SMJ/A294). The interviewers had the freedom to add any questions to maintain the conversational flow and to explore a deeper understanding of the participants’ experiences. A single author (E.L.) conducted all of the interviews to maintain the consistency of the interview structures and to minimize the bias during the interviews. Interviews were conducted until thematic saturation was achieved.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistical analysis for the quantitative survey study was performed using SPSS statistical software version 27.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk, NY). For the qualitative study, the interviews were audio recorded and transcribed using the transcription software otter.ai (Los Altos, CA).7 Five authors (E.L., S.T., L.S., E.G., and R.S.) listened to the audio and read the deidentified transcripts generated by otter.ai for accuracy. Using the Moustakas method, four authors (E.L., S.T., L.S., and E.G.) independently analyzed each interview script. Using inductive reasoning, the authors isolated important texts into meaningful categories called codes. Similar codes were then grouped into themes. Final themes, codes, and text examples were discussed by four authors and any conflicts were resolved by consensus after discussion. The codebook was then developed using a directed approach to content analysis.

To ensure the trustworthiness of data, authors used bracketing to identify their own biases regarding virtual interviews before the start of the study. Investigator triangulation was then used to ensure data validity. This study was approved by the institutional review board offices.

Results

Quantitative Survey

The survey was e-mailed to 158 fourth-year medical students at one allopathic medical school and was posted on a social media page for one allopathic medical school and one osteopathic medical school. A total of 46 participants completed the survey. It is difficult to deduce the exact response rate because the survey was distributed using a snowball approach. Based on the known total number of medical students at one allopathic medical school, however, the response rate was 29.1%. The majority of the participants were Asian (n = 22, 47.8%), female (28, 60.9%), and aged between 26 and 30 years old (30, 65.2%). The most common specialties were Internal Medicine (20, 43.5%) followed by Family Medicine (8, 17.4%). Participants applied to a mean of 77 residency programs (interquartile range [IQR] 45.3–100) and reported that they would have applied to a mean of 58 residency programs (IQR 45.0–75.0) if applied during pre-COVID times. The mean number of interviews offered was 17 (IQR 11–23), and the mean number of interviews attended was 15 (IQR 11–18) (Supplemental Digital Content Appendix 2, http://links.lww.com/SMJ/A295).

The majority of the participants reported attending virtual social events (38, 84.78%) and found it helpful or very helpful (25, 54.34%). Similarly, the majority attended a virtual information session before the interview season (40, 86.96%) and also found it helpful or very helpful (31, 67.39%). The most beneficial aspect of the virtual interview was saving money on travel (31, 77.39%). In contrast, the least beneficial aspect of the virtual interview was missing the opportunity to explore the culture of the program (16, 34.78%), followed by missing exploring the city and surrounding area (11, 23.91%). Approximately half of the participants faced technical issues during virtual interviews (23, 50.00%), with the Internet connection being the most common technical issue (20, 43.48%). The mean overall comfort level throughout the virtual interview process from scale 1 through 10 was 8 (IQR 7–9) (Supplemental Digital Content Appendix 3, http://links.lww.com/SMJ/A296).

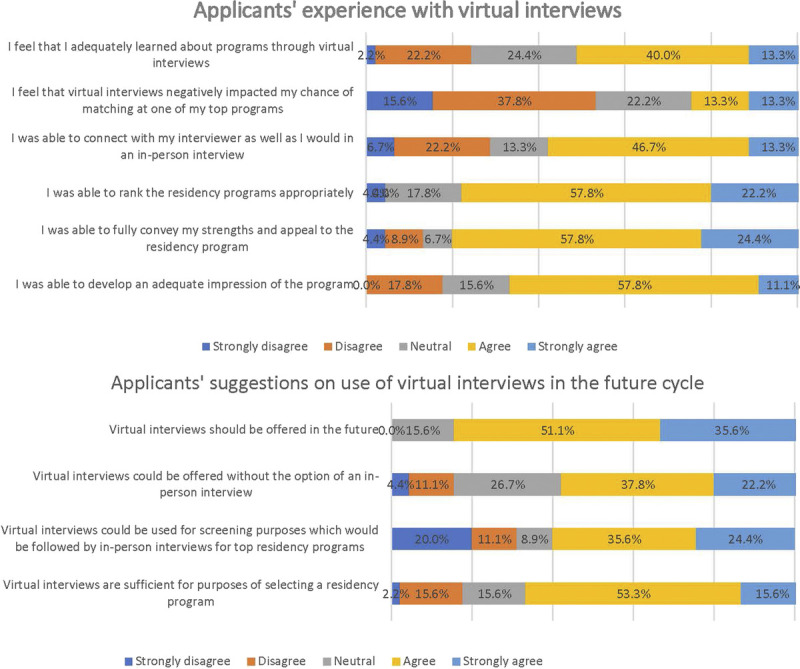

When asked about the virtual interview experience, more than half of the participants agreed or strongly agreed that they were able to adequately learn about the programs, connect with interviewers as they would in an in-person interview, rank the programs appropriately, fully convey their own strengths and appeal, and that they developed an adequate impression of the program (53.3%, 60.0%, 80.0%, 82.8%, and 68.9%, respectively). The majority of the participants were neutral, disagreed, or strongly disagreed that virtual interviews negatively affected their chance of matching at one of their top programs (75.6%; Fig.).

Fig.

Applicants’ experience and suggestions in virtual interviews.

Participants were then asked about suggestions on the use of virtual interviews in future application cycles. The majority of the participants reported that virtual interviews should be offered in the future (86.7%) and noted that it was sufficient for selecting a residency program (68.9%). Approximately half of the participants said that virtual interviews could be offered without in-person interviews or as a screening process that is followed by in-person interviews (60.0% and 60.0%, respectively; Fig.).

Qualitative Survey

The lead author (E.L.) interviewed 14 participants between March and April 2021. Each interview lasted from 15 to 45 minutes. Ten participants were from an osteopathic medical school and four participants were from an allopathic medical school. No participant had prior experience with virtual interviews. They participated in an average of 16 virtual interviews (range 9–29) for the past Match cycle. After the analysis of the interviews, the participants’ virtual residency interview experiences were divided into four major themes:

Virtual interviews offered many advantages (Table 1)

Virtual interviews posed unique challenges (Table 2)

Residency programs need more organizational improvements (Table 3)

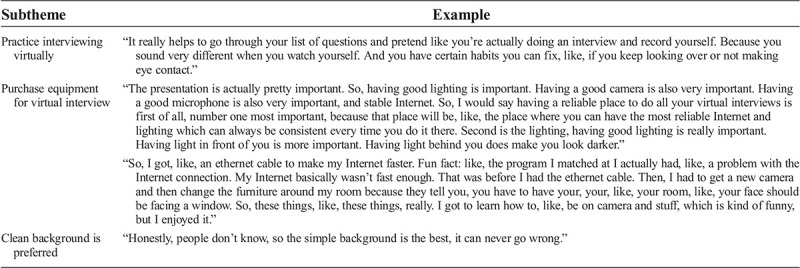

Virtual specific preparations are needed (Table 4)

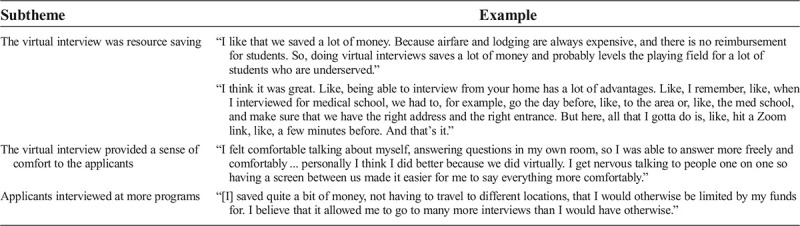

Table 1.

Virtual interviews offered many advantages

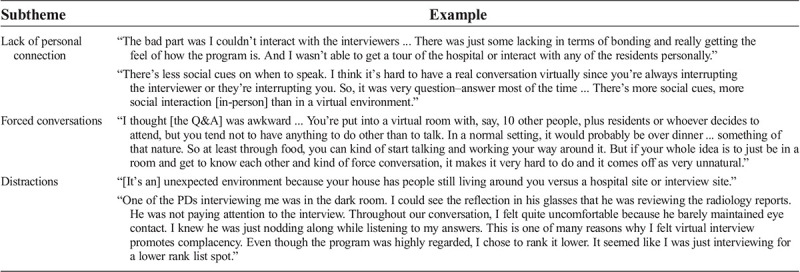

Table 2.

Virtual interviews posed unique challenges

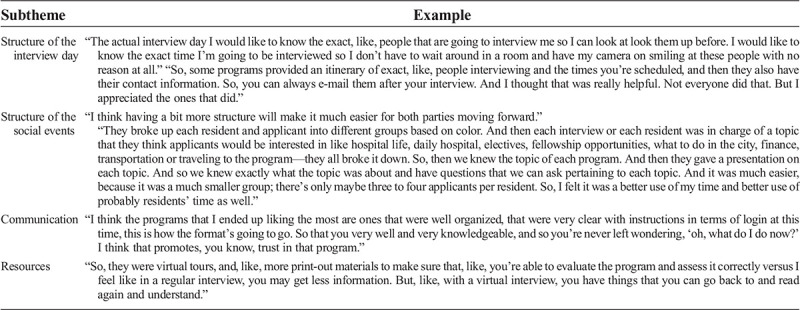

Table 3.

Residency programs need more organizational improvements

Table 4.

Virtual specific preparations are needed

Virtual Interviews Offered Many Advantages (Table 1)

Participants described numerous advantages from their experiences with virtual interviews during the residency interview process. We explored various subthemes, including resource saving, a sense of comfort, and the increase in applicant interviews at programs.

The Virtual Interview Was Resource Saving

All of the participants reported that the virtual interview process was resource saving in terms of cost and time. Participants explained how the virtual interview process enabled them to reduce costs associated with travel, including airfare and lodging expenses. One participant reported that the cost-savings aspect of the virtual interviews provided an “equal playing field for a lot of students who are underserved.” Moreover, the virtual interviews allowed participants to save time and energy in planning for the trips and traveling, which “allowed me to go to many more interviews than I would have otherwise.”

The Virtual Interview Provided a Sense of Comfort to the Applicants

Participants reported that virtual interviews conducted at home had “naturally promoted a level of comfort” to otherwise stressful interview days. A participant who has always been nervous about the interview process found this to be an important advantage of virtual interviews and noted: “a screen between us made it easier for me to say everything more comfortably.” One participant described how the comfort of the home allowed her to portray herself better: “In a virtual interview, like, it’s kind of only in that box and so what you say, like, matters more, and so I felt that I was able to like portray, like, what I wanted or say what I wanted to say.”

Applicants Interviewed at More Programs

Because of the nature of virtual interviews, applicants were not as limited by time or costs as in previous residency application cycles. This has resulted in more interview participation and “increase[d] chances of matching.” Some participants even scheduled multiple interviews on the same day: “I liked how I was able to schedule interviews, and I can do it just in the morning or just in the afternoon, or whole day. And I can do another interview the next day without traveling.”

Virtual Interviews Posed Unique Challenges (Table 2)

Participants described the unique challenges faced during the virtual interview process. We explored subthemes, including lack of personal connection, forced conversations, and distractions.

Lack of Personal Connection

One of the most commonly reported challenges among the interviewers was the impersonal nature of the virtual interview process. Participants discussed difficulty detecting social cues such as eye contact and body language, which has prevented adequate rapport building with interviewers and hindered them from adequately representing themselves in the interview. Participants also discussed how they were unable to get “a good feel” for each program and how virtual interviews could not “replicate” the traditional in-person interviews because it is “missing physical components.” The most common reasons were an inability to visit the cities and facilities or directly interact with residents in their work environment.

Participants also believed that all of the programs started to “blend together” because all of the interviews were done in the same home environment: “Virtual interviewing—sometimes things blend together ... you were basically, like, sitting home for, like, in front of a laptop usually in the same place wearing the same clothes.” One participant explained how this had made it difficult for him to make a rank list: “I feel like I’m missing out on the experience of actually seeing the residents and the people there. Because now I’m in the midst of making my rank list, I’m having a hard time differentiating programs because of the virtual interviews.”

Forced Conversation

Because of the nature of the virtual format, participants reported that conversations were often “awkward” and “unnatural.” They often felt “forced” to ask questions during the question and answer session, exacerbating “Zoom fatigue.” One participant described, “What ended up happening a lot of times, and I think a lot of my other fellow applicants can agree, is because of a very prolonged question and answer session, I myself sometimes feel forced to try to come up with a question just to fill in the void of having someone answer my question, even though I may not have any more questions in particular.” Many participants also felt that question and answer sessions were “too large,” thereby further inhibiting natural conversation.

Distractions

Many participants encountered distractions throughout virtual interviews. The majority of the participants reported that it was difficult to ensure a quiet home environment for the entirety of every interview because of family, roommates, pets, or outdoor noises. Internet malfunctions also were regularly cited as a distraction. Some participants reported that interviewers often were distracted, with a few performing clinical duties while simultaneously interviewing. One participant, in particular, noted that an interviewer was “reviewing the radiology reports” throughout the interview process, as evidenced by the computer screen reflection on the interviewer’s glasses. Because of this, the participant “felt virtual interview promoted complacency” in programs and “chose to rank [that program] lower” even though the program was “highly regarded.”

Residency Programs Need More Organizational Improvements (Table 3)

Participants provided suggestions on how residency programs can reconstruct their virtual interviews and social events to provide an optimal experience for future interview cycles. Various subthemes include the structure of the interview day, the structure of the social events, the communication between programs and applicants, and the resources provided to applicants.

Well-Coordinated Interview Day

One of the most commonly reported areas for improvement was in the overall organization of the virtual interviews. Participants noted that it was extremely helpful to receive a full schedule of the day’s events “where they give you the exact time of when your interview is supposed to be,” names and contact information of the interviewers “so [applicants] can always e-mail them after the interview.” Participants also appreciated when the coordinator gave instructions about when to have cameras on and off, and provided short breaks throughout the interview day to minimize the Zoom fatigue.

The participants reported that it was helpful when programs then adhered to their reported schedule very closely, so “it was very clear on what time we can log in, what time we can log off,” and there were no surprises on interview day. Some participants reported that some interview days were too long on a virtual platform and suggested the ideal interview day length to be approximately 3 to 4 hours. In addition, participants preferred programs to use a consistent virtual platform for their virtual interview (whether that be Zoom, Webex [Cisco, San Jose, CA], or others), rather than switching between multiple platforms because learning “how to operate a new interface was a bit challenging.” Specifically, it was noted that “Zoom was the best” interface to use.

Social Event Structure

Most participants reported that unstructured question and answer sessions with current residents made it difficult to learn more about the culture of the program and get to know the residents themselves. The participants reported that they felt pressured to ask questions even if they did not have questions and that it was draining to be required to have cameras on during these times.

Many participants stated that social events that have “a bit more structure would make it much easier for both parties moving forward.” This could include incorporating a game (scavenger hunt), small group break-out rooms, or small presentations about resident life put on by current residents. Participants also recommended that programs provide an anonymous link for applicants to post their questions “Because sometimes people want to ask a question, but they’re scared of asking it.”

Participants recognized that social events typically would be structured around drinks or a meal in an in-person format that can promote natural conversation topics. Many participants appreciated the programs that made an effort to send them gift cards, food service credits, or small gifts with the program logo on them. For the programs that send food service credit, participants felt as though they were able to “go get your own food, and then really have a meal, a sit-down meal, and then, like, talk over that.” One participant stated that sharing a meal this way “promotes a calming effect ... a medium in which to bond over.”

Communication between Programs and Applicants

Many participants suggested clear communication between the programs and the applicants before and during the virtual interview process. This can be achieved by providing a timely agenda for the day and “having everything in place at least a week before and not, like, the day before” and having coordinators available during the interview day to answer any questions or help with technical difficulties.

Virtual Resources

Many programs provided various virtual resources for the virtual interview cycle, including virtual tours of hospital facilities and informational videos. Participants found these resources helpful in lieu of being able to experience the facilities firsthand and even felt as though “in a regular interview, you may get less information.” Participants appreciated receiving resources before the interview to allow sufficient time to learn about the program and to form appropriate questions for interview day. Participants found video resources to be especially helpful “because you can always go back and rewind and, like, relive the experience.” Some programs invited applicants to join their didactic sessions and morning reports. This allowed applicants to experience the team dynamics that often were missed during virtual interviews.

Virtual Specific Preparations Are Needed (Table 4)

Virtual specific preparations were needed to provide a successful virtual interview experience. Most participants held a virtual mock interview with mentors, friends, and families who could critically evaluate how the applicant sounded and presented virtually. In addition, mock interviews helped to identify any issues with video conferences, practice with technology, and identify issues related to connectivity. Some participants videotaped themselves to closely monitor for behaviors and speech on camera, which helped with “certain habits you can fix,” such as “not making eye contact.”

Participants also purchased equipment, including an ethernet cable, a microphone, a webcam, and a ring light to better create the interview experience. The majority of the participants identified good lighting to be one of the most important preparations in presenting themselves on camera. Also, having a stable Internet connection was another essential factor in providing a smooth virtual experience for both applicants and interviewers. A participant reported, “Having a reliable place to do all your virtual interviews” with “the most reliable Internet and lighting which can always be consistent” to be “one of the most important” factors.

Furthermore, the participants used backgrounds to express their individuality from a simple white backdrop to backgrounds showcasing their hobbies, achievements, and even a banner of the residency program for which they are interviewing; however, the majority preferred the clean white background to be the best that “never goes wrong.”

Discussion

In light of the unabating COVID-19 pandemic, virtual interviews will continue in the upcoming 2022 ERAS cycle; therefore, it is essential to recognize and learn from the experiences of the previous application cycle. Our study collected comprehensive data regarding the virtual residency interview process through a combined quantitative and qualitative approach. The quantitative survey captured objective data using Likert scales, which were complemented with qualitative interviews to provide in-depth information on the applicants’ opinions and experiences that otherwise could have been missed by only using structured surveys. To our knowledge, this is the first such combined study that explores experiences of the virtual interview by the residency applicants. Based on our unique approach, we provide principles and recommendations to both programs and applicants for the upcoming interview season.

Despite the many challenges faced during the unprecedented 2021 ERAS cycle, we found that applicants had an overall positive experience with the virtual interview. Many participants from the interview reported that they would prefer a virtual interview over an in-person interview if they were given a choice in the future. Most of the participants in the survey agreed that virtual interviews should be offered in the future, and more than half agreed that virtual interviews were sufficient for selecting a residency program. Similar positive virtual interview experiences were reported by the University of Chicago survey during the Complex General Surgical Oncology (CGSO) interview day.8 Approximately half of the interviewees preferred virtual interviews and more than 75% reported that they were able to convey themselves well.8

Contradicting results, however, were shown in an MD Anderson study during the CGSO season. Although both candidates and faculty gave an overall high rating to virtual interviews, a majority of the interviewees reported a preference for an in-person interview.9 Similarly, Hill et al found that a majority of the candidates for the CGSO season would not choose a virtual interview over an on-site interview, with those who interviewed in person at the beginning of the season being more likely to respond in this manner.10 This discrepancy in perception of the virtual interview can be explained by the demographics of the participants and the timing of the survey completion. Although other studies conducted the survey on fellowship applicants participating in the CGSO season, our study was conducted on residency applicants applying to various specialties. As such, our findings provide a wide range of experiences and recommendations that are more broadly applicable to all of the applicants participating in the ERAS cycle regardless of their specialties. Moreover, CGSO applicants who interviewed in person at the beginning of the season but later transitioned to virtual interviews are more likely to provide lower ratings on their virtual interview experience because the in-person experience cannot be completely replicated nor fully appreciated in a virtual setting only.10

Our study found resource saving to be the most beneficial aspect of virtual interviews, which outweighs the challenges of virtual interviews. The virtual interview allows increased flexibility, convenience, and efficiency that are time, cost, and energy saving. The Association of American Medical Colleges’ (AAMC) “Cost of Applying to Residency Questionnaire Report” found that the fourth-year medical students spent on average $3422.71 each for interviews, including travel costs, lodging, and meals.11 Kerfoot et al reported that travel expenses accounted for 60% of the overall interview expenses obtained primarily by student loans.12 Similarly, Watson et al found that 62.3% of general surgery residents spent more than US$4000 and 21.7% spent more than US$8000 for fellowship interviews.13 As a result, some fellowship programs were offering videoconference as a viable option before the COVID-19 era, when geographic location and/or financial situations limited the ability of applicants to present for in-person interviews.14 The high cost of the interview process puts an additional burden on rising student debt. Understandably, cost-savings was an important advantage for applicants that outweighs the challenges inherent to the virtual interview process: “I feel like there are so many upsides in terms of saving money and time ... And if I had the option for fellowship interviews that keep it virtual, I would probably like that.” In addition, the time- and energy-saving aspect of virtual interviews allowed applicants to participate in more interviews that would otherwise not be possible if interviews were done in-person: “I liked how I was able to schedule interviews, and I can do it just in the morning or just in the afternoon, or whole day. And I can do another interview the next day without traveling.”

The convenience of virtual interviews has created an unwanted consequence of interview hoarding among competitive candidates, however.15 An applicant expressed the frustration of interview hoarding: “Competitive applicants apply to a lot of programs, and it’s our belief that they took up a lot of the interview spots even though they didn’t have any desire to come to that program ... but for mediocre or, like, a not as competitive applicant, they might have missed out on a chance to interview at a program that they might have matched at if a more competitive applicant hadn't applied.” In concern for interview hoarding, the AAMC’s chief medical educator wrote in a letter: “We are seeing students in the highest tier receiving a larger number of interviews per person than in past years, leaving other students—including those in the middle of the class—with fewer interviews than we would anticipate based on their qualifications.”15 The AAMC letter also requested that applicants consider releasing interview slots if they are holding more than they need.15 In response to interview hoarding, some program directors even reported forgoing interview offers to top applicants who historically have matched elsewhere and instead favor lower tier candidates.16,17

Applicants faced numerous challenges that were unique to virtual interviews. Because of the lack of a dynamic interactive environment that was offered by in-person interviews, the majority of the applicants reported impersonal aspects to be the most significant limitation of virtual interviews. The nature of the virtual format has limited an opportunity for applicants to gain an accurate assessment of the culture of the residency programs, as well as the city life of their potential future home: “The biggest thing was just simply not being there in person to see the hospitals, see the staff, and really didn’t actually meet the residents and the faculty there ... No matter how much virtual interviews try to replicate, it’s still missing those physical components. That is actually very important when you’re trying to decide where you want to train for the next 3 to 4 years or however long.” Lewit et al further supported our finding that applicants had a limited opportunity to get to know the programs in the virtual interview.18 To counteract this unique challenge of virtual interviews, residency programs expanded the availability of resources for the applicants through multiple short videos, updated residency Web sites, active social media presence, and invitations to morning reports or didactic sessions.19 Videos included short testimonials from prior residents, personal stories from residents and faculty, local amenities and attractions, a virtual department tour to include any great resident lounges or educational amenities, a day in the life of a resident video, and short welcome videos by the program director and department chair.19 One applicant reported these resources to be especially helpful during the ranking process as she was able to “go back and rewind ... relive the experience.” Applicants have provided suggestions on ways to optimize the virtual interview experience for the upcoming cycle, including more organized events and more transparent communication for a smoother virtual experience. According to recent data, key points for a successful interview day include a carefully coordinated interview day, individualized interview experience, preinterview dinner, and postinterview feedback.19 In addition, our participants suggested that social events be more structured. Typically, during in-person interviews, programs offer social events in a more casual setting to allow applicants to get to know current residents, gauge the culture of the residency program, and ask questions that they may not feel comfortable asking in the formal environment of the interview. This year, however, these “social events” were held on a virtual platform such as Zoom or Webex, and many used an unstructured format. Applicants often described social events to be “awkward” and often forced conversation in an unnatural way. The recommendations for structured social events are as follows:

Breakout rooms with smaller groups so that applicants can ask questions in a less intimidating environment

Having preformatted topics for discussion and questions

A link for anonymous questions that applicants can use to ask questions that they may otherwise not feel comfortable asking openly

The recommendations for programs on an interview day are as follows:

Providing interview day schedule and interviewer information before interview day

Using a virtual platform that the applicants are familiar with (eg, Zoom, Webex)

“Goodies” and/or lunch vouchers (eg, $20 Uber Eats, GrubHub) to applicants

The recommendations for applicants on an interview day are as follows:

Check the time zone of the interview day

Find a quiet place with an area with a nonbusy background

Be aware of the window placement in your background

Test Internet and equipment before the interview (Web cam, ring lights, speakers, microphone)

Join the interview session at least 10 minutes early to resolve any technical difficulty

Have the contact information of the program coordinator in case of unexpected technical difficulties during the interview

There are several limitations to the study. The majority of the responses came from two academic institutions, which limit the generalizability of the results. We included both osteopathic and allopathic medical schools from two different geographic areas to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the virtual interviews. We cannot, however, be certain how transferable our findings would be to students from other medical schools in different geographic locations. As such, given the low response rate, our finding can only be presented as preliminary information and observations on the subject.

Both our qualitative and survey-based studies were limited by recall bias and small sample size. We hope that larger, broader studies will be completed for future studies. Finally, the survey study had the inherent limitations of survey studies, including ascertainment bias and data reliability.

Future studies are warranted to advance our current findings. A longitudinal study on applicants for subsequent cycles can provide trends in applicants’ perspectives on the interview process. In addition, a study on the interviewers will give valuable insight for comparison with applicants and explore suggestions for improvement based on interviewers’ perspectives.

Conclusions

We conducted a combined quantitative survey and qualitative interviews to gain a comprehensive understanding of the virtual interview experience from the applicant’s perspective. We found that virtual interviews were overall well experienced by applicants, with resource saving being the most beneficial aspect of virtual interviews. There remains room for improvement, however, including organization, communication, and virtual etiquette for future ERAS cycles. We hope that our findings provide insight into the applicant’s perspective on the virtual interview experience and help optimize virtual interviews for future cycles.

Footnotes

Present address: Western University of Health Sciences, Pomona, California.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text, and links to the digital files are provided in the HTML text of this article on the journal’s Web site (http://sma.org/smj).

The authors did not report any financial relationships or conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Samantha Terhaar, Email: sterhaar@gwmail.gwu.edu.

Leyn Shakhtour, Email: lshakhtour@gwmail.gwu.edu.

Eleanor Gerhard, Email: egerhard@gwmail.gwu.edu.

Margaret Patella, Email: mpatella@gwmail.gwu.edu.

Rohan Singh, Email: rohanameetsingh@gmail.com.

Philip E. Zapanta, Email: pzapanta@mfa.gwu.edu.

References

- 1.Wolff M, Burrows H. Planning for virtual interviews: residency recruitment during a pandemic. Acad Pediatr 2021;21:24–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zuo KJ, Retrouvey H, Wanzel KR. Factors that affect medical students’ perception and impression of a plastic surgery program: the role of elective rotations and interviews. Ann Plast Surg 2019;82:224–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byrne L. Coalition for Physician Accountability releases recommendations on 2021-22 residency season interviewing. https://www.nrmp.org/coalition-recommendations-2021-22-interviewing. Published August 25, 2021. Accessed October 10, 2021.

- 4.Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design. Choosing among Five Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris PA Taylor R Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zoom . Home page. https://explore.zoom.us/meetings. Accessed April 21, 2021.

- 7.Otter Voice Meeting Notes . https://otter.ai. Accessed April 26, 2021.

- 8.Vining CC Eng OS Hogg ME, et al. Virtual surgical fellowship recruitment during COVID-19 and its implications for resident/fellow recruitment in the future. Ann Surg Oncol 2020;27(suppl 3):911–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Day RW Taylor BM Bednarski BK, et al. Virtual interviews for surgical training program applicants during COVID-19: lessons learned and recommendations. Ann Surg 2020;272:e144–e147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hill MV Ross EA Crawford D, et al. Program and candidate experience with virtual interviews for the 2020 Complex General Surgical Oncology interview season during the COVID pandemic. Am J Surg 2021;222:99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Association of American Medical Colleges . The cost of applying for medical residency. https://students-residents.aamc.org/financial-aid-resources/cost-applying-medical-residency. Accessed April 21, 2021.

- 12.Kerfoot BP, Asher KP, McCullough DL. Financial and educational costs of the residency interview process for urology applicants. Urology 2008;71:990–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watson SL Hollis RH Oladeji L, et al. The burden of the fellowship interview process on general surgery residents and programs. J Surg Educ 2017;74:167–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daram SR, Wu R, Tang SJ. Interview from anywhere: feasibility and utility of web-based videoconference interviews in the gastroenterology fellowship selection process. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:155–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murphy B. Residency Match: concerns emerge about distribution of interview slots. https://www.ama-assn.org/residents-students/match/residency-match-concerns-emerge-about-distribution-interview-slots. Published January 12, 2021. Accessed April 20, 2021.

- 16.Weissbart SJ Kim SJ Feinn RS, et al. Relationship between the number of residency applications and the yearly Match rate: time to start thinking about an application limit? J Grad Med Educ 2015;7:81–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berger JS, Cioletti A. Viewpoint from 2 graduate medical education deans application overload in the residency Match process. J Grad Med Educ 2016;8:317–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewit R, Gosain A. Virtual interviews may fall short for pediatric surgery fellowships: lessons learned From COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2. J Surg Res 2021;259:326–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel TY Bedi HS Deitte LA, et al. Brave new world: challenges and opportunities in the COVID-19 virtual interview season. Acad Radiol 2020;27:1456–1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]